CHD was the most prevalent congenital anomaly (60.9 per 10,000, 95% CI 59.0–62.8) in England in 2018, with 1767 babies born with severe cardiac defects. 1 In the UK, 30-day survival rates for complex procedures including Norwood (93.2%) and systemic to pulmonary artery shunts (93.3%) (2017/18 data) 2 continue to improve, but the early post-operative period remains a critical time. Reference Crowe, Ridout and Knowles3 Quality improvement projects using home monitoring programmes have demonstrated some benefits globally. Reference Ghanayem, Hoffman and Mussatto4–Reference Steury, Cross and Colyer8 However, United Kingdom cardiac safety standards at discharge did not exist prior to this project, and there were no other community-based parental early warning tools available for infants with complex CHD.

A United Kingdom qualitative study Reference Tregay, Brown and Crowe9 exploring parents’ perspectives of caring for a child with complex needs found that some parents could describe symptoms of deterioration, whilst others could not identify any early warning signs. Barriers to obtaining speedy assistance included not being taken seriously, long waiting times, and lack of protocols in the emergency department. The authors concluded that there was a role for home monitoring; parents should be encouraged to seek early advice, and front-line health professionals need access to information enabling appropriate and effective management. A further study identified that not all parents were taught signs of deterioration or given written information specific to their baby prior to discharge; three themes were highlighted: mixed emotions about going home, knowledge and preparedness, and support systems. Reference Gaskin, Barron and Daniels10

In 2012, the Congenital Heart Assessment Tool (CHAT) was developed to support decision-making by families and children’s community teams to improve safety, quality, and standardisation of care, and communication. Reference Gaskin, Barron and Daniels10 Parents’ perceptions of the acceptability and feasibility of using the CHAT at home were subsequently evaluated in a single centre project. Reference Gaskin, Wray and Barron11 Using the CHAT helped parents to identify signs of deterioration, enhanced their confidence, and empowered them to articulate their infant’s needs clearly and in a timely manner. Reference Gaskin, Wray and Barron11

The aim of this QI initiative was to implement the CHAT across three additional children’s cardiac centres and further evaluate it in collaboration with parents and carers, local community stakeholders, nursing, and medical service leads, thereby contributing to the vision of developing robust bundles of care to support acute specialised care in the community. This paper follows the SQUIRE guidelines Reference Ogrinc, Davies, Goodman, Batalden, Davidoff and Stevens12 and presents phases six to eight of the QI project (Fig 1), including qualitative evaluation of the CHAT through simulation workshops with stakeholders and parents, and presents the updated tool, CHAT2. Phases 1–5 are reported elsewhere. 13

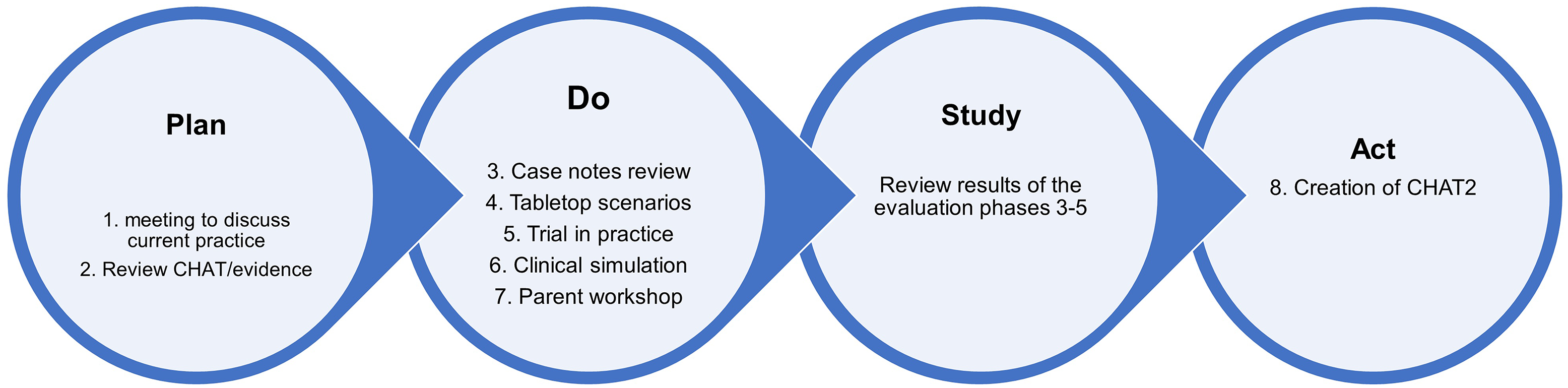

Figure 1. The plan, do, study, act cycle.

Methods

The plan, do, study, act (PDSA) QI design (Fig 1) was used to formatively evaluate feedback, directly influencing the quality and efficiency of the CHAT. The QI initiative was funded by the Health Foundation “Innovating for Improvement” programme and conducted over an 18-month period, comprising a 3-month set-up phase (August–October 2016) and 12 months implementation (November 2016–October 2017) at four specialist children’s surgical centres (London, Birmingham, Southampton, and Newcastle) and the University of Worcester. The implementation phase was extended to include stakeholders attending the Little Hearts Matter open day (March 2018).

Intervention

The CHAT Reference Gaskin, Barron and Daniels10 is based on a traffic light system divided into green (low risk), amber (intermediate risk), and red (high risk). CHAT was slightly modified following a review during the “Plan” stage, and this modified version “CHATm” (see paper 1) was used throughout the QI project. The clinical parameters (e.g., expected oxygen saturations) can be individualised with the Consultant’s preferred parameters. Parents are taught to assess their infant’s activity level, skin colour, breathing, circulation, feeding, and weight and to decide actions based on the information in the green, amber, and red columns. The aim is to effectively prepare parents before discharge, ensuring that they understand how to assess their infant; they are taught to assess their infant daily or at any other time if their infant’s condition has changed. Parents are also taught to interpret the significance of the signs, to record their findings in a daily diary, and to contact health care professionals as guided by the tool. An assessment of green indicates that parents can “carry on as normal”; any sign in amber triggers a phone call to the ward to discuss management; any sign in the red column indicates the infant is seriously ill and parents are advised to phone for an ambulance (call 999) immediately.

Participants

Phase 6 (Clinical Simulation workshop June, 2017). Parent members of Little Hearts Matter were invited to participate via the charity website and social media. Local Community Children’s Nurses, General Practitioners, three cohorts of Children’s Nursing students at the University of Worcester, Nurses, and Consultants from the four children’s cardiac centres were invited to take part via personal communication, email, and social media. We aimed to involve 10–15 participants.

Phase 7 (Parent workshop). All parents/carers of a child with a univentricular heart condition who had undergone cardiac surgery and were attending the Little Hearts Matter (LHM) open day (March 2018) were invited to participate. There were no exclusion criteria to enable inclusivity. A variety of workshops were offered simultaneously at the event, and parents were free to choose which one to attend. We hoped to engage 10 parents.

Study of the Intervention (CHATm)

Both phases used clinical simulation as the investigative methodology. Reference Lamé and Dixon-Woods14–Reference Cheng, Grant and Auerbach15 For phase 6, simulation was used to assess feasibility, study any safety issues, and the parental preparation environment and to optimise design and implementation of the CHATm. Six scenarios were used: four role plays of “telephone conversations” and two “parent preparation for discharge” simulations.

For phase 7, the CHATm was evaluated by parents/carers, based on one of the clinical scenarios (Table 1) and their own experiences of taking their infant home from hospital for the first time following the first stage of cardiac surgery.

Table 1. Clinical scenario 1 (parent’s version)

Measures

The role-play scenarios (phase 6) were video-recorded to retrospectively review and analyse decision-making discussions during the role play. Participants were also asked to feedback verbally about their experience (acceptability), evaluating the CHATm for ease of use (usability), and suggestions for implementation in practice (feasibility). This feedback was audio-recorded and written notes were taken.

The workshop (phase 7) was audio-recorded to capture parents’ verbal comments about using the CHATm for one clinical scenario. There was also an additional written feedback sheet, enabling the capture of information from those who preferred not to speak up in the group.

Validity

To ensure internal validity, simulation objectives were developed and discussed with the participants before the exercises. The clinical scenarios included details about the situation, patient, parent and facilitator details, scenario script, room setting, equipment, and team roles.

Using simulation to evaluate the CHATm reduced the environmental, physical, social, and psychological complexity influencing external validity and generalisability of the findings for implementation in a clinical environment where a parent is taking home their fragile infant for the first time. Reference Cheng, Auerbach and Hunt16–Reference LeBlanc, Manser, Weinger, Musson, Kutzin and Howard17 This can potentially weaken confidence in how far it is possible to generalise from these controlled conditions. Reference Vissers, Heyne, Peters and Guerts18–Reference Hamstra, Brydges, Hatala, Zendejas and Cook19 However, the participating cardiac nurse specialists were very experienced in preparing parents for discharge and were able to utilise their knowledge, understanding, and skills within the evaluative exercise. Furthermore, utilising the same scenarios for phase 7 enhanced the internal and external validity as parents were able to draw on their own personal experiences of going home with their infant and what the CHATm would have meant for them had it been available.

To ensure fidelity and authenticity of the simulation, Reference Lamé and Dixon-Woods14,Reference Hamstra, Brydges, Hatala, Zendejas and Cook19–Reference Tun, Alinier, Tang and Kneebone20 the scenarios were written using clinical experience of QI team members. The simulation environment mimicked a real ward setting and some participants dressed in uniform to enhance the simulation. Unfortunately, we were unable to recruit parents to participate in phase 6. Therefore, the parental roles were played by one of the specialist cardiac nurses who had the experience of managing these situations in clinical practice and was able to add phenomenal and semantic content to the role play. Reference Dieckmann, Gaba and Rall21 However, one of these scenarios was used for discussion during phase 7, bringing parents’ perspectives to the evaluation.

Analysis

The recordings were transcribed and thematically analysed Reference Braun and Clarke22 by members of the QI team and a LHM representative. Notes kept throughout the workshops were compared with the key points arising from the transcriptions to identify any ideas, thoughts, or notes that had not been captured during the summary.

Ethics

National Health Service Ethical Approval was not required; however, agreement was received from each of the individual children’s cardiac units’ QI Teams. The University of Worcester Institute of Health and Society Ethics Committee approved the clinical simulation exercise and parent workshop. To fulfil conditions of this approval, participants for phases 6 and 7 were given an information sheet and asked to provide written consent.

Results

Phase 6: Four nurses (two ward nurses, one Clinical Nurse Specialist, one Advanced Nurse Practitioner) and three Children’s Nursing students (two third year, one first year) participated, along with the Chief Executive of the Charity.

Four themes related to recommendations were identified (Table 2): suggestions for improved documentation; aspects to consider during preparation and in dialogue with parents; preparation of health care professionals; and communication.

Table 2. Phase 6 recommendations

One participant commented, ‘This was a really good way of testing the tool, as all involved were learning to use the tool at the same time as doing this as a clinical scenario’

Phase 7: Five parents (three mothers, two fathers) of four children with functionally univentricular hearts attended the workshop. The children ranged in age from 4 to 22 years, three had undergone stage 3 surgery (Fontan procedure), and the fourth had undergone stage 2 (Glenn procedure).

One key theme emerged: “what parents know versus what professionals know”

All parents correctly identified a red trigger using the CHATm. However, their discussion indicated that in their personal experience additional factors were at play when deciding whether to phone for an ambulance (red) or phone the ward for advice first (amber), such as knowing the system, knowing who to contact [who had the right knowledge], and knowing their infant’s “normal”. Parents discussed the “lack of knowing” of health care professionals in primary care, pre-hospital and emergency departments, such as “arriving at your local DGH and then saying you need to contact the [specialist hospital] and no-one there knows what to do and you’re stuck in A & E trying to get through [to the specialist hospital] on a mobile phone … it’s just easier to do that conversation at home and get the advice first”.

They talked about paramedics’ lack of understanding of CHD “The ambulance came out when she was a baby. They were horrified that we didn’t have oxygen at home, because her saturations were so low” another parent said “I did always find when my son was little, I was always having to say that giving him home oxygen won’t make any difference, it’s the heart that’s the problem not the lungs”. So, for this group of parents they knew from experience that they “would always phone a ward before an ambulance to get their advice, because phoning an ambulance … when you get adult paramedics who don’t understand your child”.

Modifications to the intervention (Phase 8)

This QI project evaluated the CHATm through seven phases (Fig 1) resulting in modifications to the tool throughout the project with a resultant finalised second version, CHAT2 (Fig 2). Using simulation identified parental preparation considerations, such as the need to commence parental discharge preparation using CHAT2 at least 5 days before the infant goes home, so that parents can get used to assessing their infant whilst support is available (Table 2).

Figure 2. CHAT2 (parent version).

Discussion

The first key finding was that the CHATm was acceptable, usable, and feasible for both clinicians and parents. However, the absence of parental participation in phase 6 and the age of one family’s “child” (22 years) in phase 7, were recognised as limitations; recall bias and changes to healthcare in the last 20 years were acknowledged as influencing factors. The workshop parents correctly ascertained the trigger from the scenario but described reluctance to phone an ambulance or go to their local hospital before getting advice from their specialist centre, because of the perceived lack of knowledge of healthcare professionals in primary and pre-hospital care, local hospitals, and emergency departments. A study Reference Gregory23 exploring student paramedics’ knowledge surrounding CHD and how prepared they felt for managing children with CHD, found that they had very little knowledge about CHD and what knowledge they did have had generally been derived from lay sources. Some student paramedics also identified that they would rely on the parents as the main source of knowledge about the infant’s condition. Fear and anxiety were identified and related to competence (or lack of competence), the emotion of the situation, fear of something going wrong, and lack of knowledge. Reference Gregory23 This links to the theme ‘what parents know versus what professionals know’ (phase 7), demonstrating implications for the dissemination of the CHAT2 more widely than the specialist cardiac centre. Preparation of staff needs to be extended to those working in pre-hospital, primary, and secondary care.

Secondly, using simulation to evaluate the tool was successful. This investigative method enabled participants to consider the ease of implementing the tool in practice and factors that would assist in ensuring a consistent approach, as well as identifying additional refinements for further improvement. Most research focuses on the role of clinical simulation in education, where it is used to train healthcare professionals, but more recently simulation has been used to support quality improvements by testing out new approaches before being implemented in practice. Reference Slakey, Simms, Rennie, Garstka and Korndorffer24–Reference Cheng, Auerbach and Hunt25 Clinical simulation can be used as a tool, device, or environment to imitate or reproduce an aspect of clinical practice in a safe environment Reference Cook, Hatala and Brydges26 and is beginning to gain recognition as an approach to evaluate healthcare. Reference Cheng, Grant and Auerbach15 Furthermore, including student children’s nurses as participants enabled the tool to be evaluated by individuals who understood children’s nursing and had some appreciation of parents’ experiences without the depth of specialist cardiac knowledge regarding the condition, surgery, or the fragility of the infants. This reflected use of the tool by community teams, with minimum underpinning knowledge of complex CHD.

Limitations

Factors potentially limiting internal validity included the use of experienced cardiac nurse specialists and less experienced student nurses as participants in the clinical scenarios. Had clinical simulation been the only method of evaluating the CHATm, this may have limited the generalisability of the findings; however, adding these findings to those from phases 1–5 of the QI project demonstrated safe and effective use of the CHATm.

Conclusions

In conclusion, phases 6 and 7 of this QI project further demonstrated the effectiveness of the CHATm in terms of triggering amber and red indicators, and parents being able to identify deterioration in an infant’s clinical condition. Useful feedback and evaluation were obtained enabling creation of CHAT2. The QI project overall had a positive impact on collaboration with the national children’s CHD standards review group, resulted in preliminary meetings being initiated with commissioners regarding Univentricular Commissioning for Quality and Innovation and encouraged the involvement of Paediatricians with Cardiac Expertise.

Next steps

A teaching package for staff was recommended to ensure full preparation: enhancing knowledge and understanding of the pathophysiology of CHD; recognition of clinical deterioration and heart failure; and parental preparation using the CHAT2. Additionally, education about using the CHAT2 when taking telephone calls from parents who have been discharged and are phoning for advice is required, including documentation and management strategies. An e-learning resource and discharge preparation pack have subsequently been developed (available at www.ccn-a.co.uk). The next stage of this work is to develop a mobile application to measure, transmit, and record parent assessment using CHAT2 to the clinical teams. There is potential for translation into different languages; extension of the tool for all infants and young children being discharged after cardiac surgery and the potential to develop another version for older children following later stages of surgery.

Acknowledgements

Amanda Daniels, Associate Lecturer in Advanced Clinical Practice, Three Counties School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Worcester, Henwick Grove, Worcester WR26AJ.

Suzie Hutchinson, Chief Executive Officer, Little Hearts Matter.

Cardiac Clinical Nurse Specialists and Children’s Cardiac Nurses from The Freeman Hospital, Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Trust.

Children’s Nursing Students, Three Counties School of Nursing and Midwifery, University of Worcester, Henwick Grove, Worcester WR26AJ.

Parents attending the LHM workshop.

Financial support

This project was part of the Health Foundation’s Innovating for Improvement programme. round 4, Unique Award Reference Number: 7709. The Health Foundation is an independent charity committed to bringing about better health and health care for people in the UK.

Conflicts of interest

None

Ethical standards

Agreement was received from each of the individual children’s cardiac units’ Quality Improvement Teams and Ethical Approval from the University of Worcester for phases 6–7.