How China's global influence is transforming the “global commons” has critical implications for the global economy, environment and international security. The “global commons” comprise the vast areas of the globe that exist outside the sovereign jurisdiction of any single state and are accessible to all – principally, the high seas, Antarctica, the atmosphere and outer space. Encompassing dimensions of the global environment essential to planetary life, they are also vital to the global political economy, supplying resources such as fisheries, seabed minerals and orbital space for satellites, as well as enabling global transportation and communications. Unrestricted access to the global commons allows technologically capable states to use them to project global military force.Footnote 1

China's expanding global reach and international activism have already made it a major actor in all global commons domains. China is pursuing new strategies and policy approaches with respect to all of them: it has emerged as a leader in global climate policy, and it is seeking opportunities to exploit what Chinese president Xi Jinping 习近平 has called the “new strategic frontiers” of Antarctica, the sea beds and outer space – all designated “assets” by China's 2015 National Security Law.Footnote 2 In the past decade, China has also joined the United States and Russia as an important player in the outer space arena.Footnote 3 Beijing's position on longstanding norms of international conduct in the maritime commons, however, has become the fulcrum upon which international concerns about China's objectives for the global commons pivot.Footnote 4 These concerns are intensified not only by what Washington sees as specific threats to US national security posed by China's challenge to freedom of navigation, like the risk of accidental and escalatory collisions at sea, but also by a more general threat to the mare liberum or “free seas” concept. First formulated by Hugo Grotius in his eponymous 1609 treatise, mare liberum has played a foundational role in establishing the principle that some planetary spaces should be maintained as global commons accessible to all.

The significance of the way that China chooses to interact with the global commons and attendant global regimes is amplified by the current international context in which multiple forces challenge prevailing international norms and rules. For example, new technologies are rendering areas of the global commons accessible to many actors for the first time, making them vulnerable to new effortsFootnote 5 by states to “territorialize” them.Footnote 6 US strategists and their allies have seen these developments as dire risks to the “connective tissue of the global economy”Footnote 7 and “essential conduits of US national power.”Footnote 8 For example, were sovereign jurisdiction extended over existing exclusive economic zones (EEZs), which are considered under mainstream interpretations of the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) to be high seas and so accessible to all, coastal states would control approximately a third of today's high seas, with uncertain impacts on international navigation.Footnote 9

China's heftier and more forward presence on the world stage, not only as a global economic and military power but also as a normative influence, makes its preferences a significant factor in determining the future of the global commons. China's well-studied cumulative behaviour with respect to freedom of navigation on the high seas has left little debate that it seeks to strengthen its jurisdictional authority over its EEZ. However, whether China's efforts to extend the scope of its sovereign control over its EEZ indicate a general strategic orientation towards the global commons as a set of open access regimes remains unclear.Footnote 10 This article examines China's interactions with two distinct global commons domains, namely the high seas and outer space, to begin to answer this question.

This article bases its analysis on three main sources of data: relevant actions and statements by Chinese government actors, published documents from official Chinese sources, and the perspectives of leading Chinese experts on these domains, drawing on an extensive review of the academic publications on this topic available through the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI) full text database. There is no question that the published writings of university and think tank-based experts provide only a limited lens on the thinking that is shaping Chinese policy. Nonetheless, even amid Xi Jinping's push to centralize authority over and tighten coordination of policies affecting Chinese security,Footnote 11 Chinese scholars’ views do inform the Chinese policy process and their writings offer insights into the concerns and priorities that may be given attention in Beijing's internal policy discussions.Footnote 12 Indeed, Chinese experts are being called upon to help authorities develop normative frames for China's international policy;Footnote 13 or, with respect to international law in particular, contribute to “lawfare” by promoting through public platforms interpretations of international law conducive to China's security interests.Footnote 14 A supplementary source of insights into Chinese expert views comes from my interviews with relevant scholars and policymakers conducted during several research trips to China from 2015 to 2017.

The article begins by describing what China's actions and official statements suggest about its stance on the scope of its jurisdictional rights in its EEZ, and what this may signify for its view of EEZs as high seas commons. Then, taking China's 2007 anti-satellite (ASAT) test and its “fallout” as a point of departure, the article assesses China's official position on the extent of sovereign control in outer space. It goes on to examine writings by Chinese experts to illuminate the perspectives underlying China's official posture on the two domains as global commons. It follows this discussion with an analysis of what this information might suggest about China's overarching posture towards the concept of open access global commons, drawing three main conclusions. Despite what China's strong rhetorical support for the principle of sovereignty as an “anchor” of international relations might augur,Footnote 15 there is little evidence that China seeks to strengthen sovereign jurisdiction across the global commons writ large. Furthermore, notwithstanding Beijing's championship of the Global South's right to development, it does not appear to be pursuing more redistributive, “fair share” governance of the global commons. Instead, China's approaches to the two global commons domains are idiosyncratic and “situational,” reflecting an assessment of how the regimes governing the two domains variably affect its strategic interests. This is a conclusion recalling Samuel Kim's observation more than two decades ago that, with respect to international regimes, China seeks to maximize its security interests while minimizing normative costs.Footnote 16 Moreover, Chinese experts’ analyses suggest that a key driver of Chinese policy towards global regimes has become how Beijing assesses an international regime's role in enabling US global dominance. In addition, although China is likely to challenge regimes it sees as reinforcing US dominance, it may support established regimes, like that for outer space, which it sees as conducive to the interests of multiple powers.

China's Official Positions on the High Seas and Outer Space Commons

Similar to Russia, China does not use the term “global commons” – generally translated in Chinese as quanqiu gongyu 全球公域 or quanqiu gongdi 全球公地 – in official documents, unlike many other governments, including the US, Japan and the European Union. However, China is party to most international treaties governing the global commons, including those relevant to the high seas and outer space. China has ratified the current (1982) version of the UNCLOS, alongside 165 other UN member states, the European Union, the UN observer state of Palestine, the Cook Islands and Niue. UN member countries that have signed but not ratified the convention include Cambodia, Colombia, El Salvador, Iran, North Korea, Libya and the United Arab Emirates; those with coastlines that are not signatories include Eritrea, Israel, Peru, Syria, Turkey, Venezuela and the United States (the US has signed the 1994 implementation agreement). Although the US has not ratified the UNCLOS, it adheres to its provisions as a codification of customary international maritime law.

China has also ratified the Outer Space Treaty (OST), the most encompassing international agreement on outer space, as well as another key treaty relevant to outer space governance, the Environmental Modification Convention (EMC) prohibiting the hostile modification of the dynamics, composition or structure of the earth and outer space. Beijing has long criticized the existing outer space regime for being inadequate with respect to outer space weaponization.Footnote 17 First in 2008 and again in 2014, it joined Russia in tabling drafts of a treaty to prevent the placement of weapons in outer space. The proposed treaty has been opposed by the US and several other countries for reasons including that it would be unverifiable and that it fails to address anti-satellite weapons amid evidence that both China and Russia are expanding counterspace capabilities. Like the US (and also Russia), China has not adopted another key component of the outer space regime, the Agreement Governing Activities of States on the Moon and other Celestial Bodies. This “Moon Treaty” describes the moon as the “common heritage of mankind” and calls for, although does not introduce, an international regime to govern the exploitation of lunar resources.Footnote 18 The Space Resource Exploration and Utilization Act, signed into law in 2015 by the Obama administration as a step towards protecting investments in resource extraction in space, as well as similar legislative action in other countries, catalysed debates in China over how to secure space resources for national development.Footnote 19

Both the UNCLOS and the regime for outer space governance give international legal weight to the idea of the global commons by defining part of the sea and outer space as beyond the bounds of states’ territorial sovereignty. The UNCLOS regime defines international waters as the seas beyond certain baselines. Territorial seas, over which states exercise full sovereign authority, end 12 nautical miles from the baseline. EEZs are designated areas that may extend by as much as 200 nautical miles beyond a coastal state's shore,Footnote 20 within which coastal states possess “sovereign rights” over resources, as well as jurisdictional powers for the purpose of managing those resources. States have sovereign control over the airspace above their territory, with most states using the Karman line of 100 km (62 miles) above sea level as delimiting sovereign airspace from outer space. The 1979 Agreement on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies designates these celestial bodies and their resources “the common heritage of mankind.”Footnote 21

Chinese law and the high seas

Nearly all states party to the UNCLOS agree that for navigational purposes EEZ waters are part of the high seas commons.Footnote 22 Most national governments, therefore, also accept that EEZs are zones in which the freedom of navigation principle applies and, as such, are waters in which peaceful military operations and scientific activities may be conducted without the consent of the coastal state.Footnote 23 This is not a question of the so-called right to “innocent passage” whereby vessels are permitted under the UNCLOS to peacefully traverse a state's territorial waters without stopping, subject to certain restrictions. The US takes this view of EEZs.

Chinese authorities interpret the UNCLOS differently with respect to the scope of national jurisdiction within EEZs, however. China asserts that because EEZs are under national jurisdiction, they are no longer “international waters” or high seas. Thus, states may lawfully require that foreign states’ militaries receive prior permission to operate within their EEZs. China defines military operations broadly to encompass surveillance as well as navigation of military vessels. Beijing references Article 88 of the Convention that reserves the high seas for “peaceful purposes,” as well as Article 58 that requires foreign states to “have due regard to the rights and duties of the coastal States” with respect to EEZs as supporting its position. In addition, Beijing cites Article 56 of the Convention, which gives coastal states jurisdiction over the regulation of marine scientific research within EEZs, as a further source of regulatory authority by states over foreign vessels operating in its EEZ.Footnote 24

Writing on the relationship between international law and Chinese domestic law, Chinese legal scholars Xue Hanqin 薛捍勤 (appointed to the International Court of Justice in 2010) and Jin Qian 钱津 observe that China lacks provisions clarifying the relative legal stature of international treaties and domestic Chinese law in China's domestic legal system.Footnote 25 Domestic laws adopted since 1992 appear to guide China's actions with respect to foreign actors in its EEZ. Among these are the 1998 Law of the People's Republic of China on the Exclusive Economic Zone and Continental Shelf and the 2001 Law on the Administration of Sea Areas, as well as a 2002 law prohibiting surveillance or surveying by foreign actors without prior permission.Footnote 26 Article 12 of China's EEZ law states that the Chinese government has the right to undertake “such measures … as may be necessary [with respect to foreign operations in its EEZ] to ensure compliance with the laws and regulations of the People's Republic of China.”Footnote 27

China began challenging foreign vessels in its EEZ in 2001 when one of its frigates confronted the US hydrographic survey ship USNS Bowditch in the Yellow Sea. Since 2009, other incidents have brought US and Chinese naval vessels into direct confrontation. In March 2009, a Chinese intelligence ship, a State Oceanic Administration maritime surveillance vessel, and a fisheries patrol vessel, along with a number of Chinese fishing trawlers, confronted and nearly collided with an unarmed US surveillance ship, the USNS Impeccable, operating in China's EEZ near Hainan.Footnote 28 In December 2013, the US guided-missile cruiser USS Cowpens was forced to take evasive measures to avoid colliding with a Chinese tank-landing ship in China's EEZ south-east of Hainan Island. Additional incidents involve airspace, including the April 2001 “EP-3 incident,” when a Chinese fighter and a US navy surveillance aircraft collided, and an August 2014 intercept by a Chinese fighter of a US patrol aircraft. In 2011, an Indian amphibious assault vessel near Vietnam's coast received a radioed warning to leave Chinese waters; in 2012, several Indian navy ships travelling to South Korea from the Philippines were “welcomed” to the South China Sea by a PLA navy (PLAN) frigate.Footnote 29 In December 2016, China seized a US underwater drone, which was conducting marine surveillance in waters within the Philippine's EEZ and possibly, although unclearly, within waters that may be part of China's Spratly Island claims.Footnote 30 Although the UNCLOS does not explicitly address drones, China's move runs counter to widely accepted definitions of the rights of foreign vessels in EEZs as well as other high seas norms.Footnote 31

Extending sovereignty into outer space?

China's actions in the high seas influence international expectations of its orientation towards outer space as a global commons, not least because China has become such a prominent actor so quickly in an arena dominated by the US and the Soviet Union/Russia since the “space age” began. China launched its first satellite in 1970; today, it has 250 satellites orbiting the earth, more than a third of which are military satellites.Footnote 32 Moreover, although China only began its human spaceflight programme in 1992, it sent its first “taikonaut” into space in 2003. In 2011, China's Tiangong-1 became the second manned space station in operation after the International Space Station (ISS).Footnote 33 It was China's 2007 use of a missile to destroy a Chinese weather satellite 500 miles above the earth that put an international spotlight on the military implications of China's rapid advances in space and the extent of its commitment to the global space regime. The test, which Beijing characterized as a high-altitude scientific experiment to collect atmospheric data but which international observers saw as an anti-satellite test, generated an immense debris cloud, putting the ISS as well as many other nations’ satellites in jeopardy. Conducted just a year and a few months after the US deputy secretary of state Robert Zoellick called upon China to act internationally as a “responsible stakeholder,” the test was seen by many in Washington and elsewhere as symptomatic of Chinese disregard for international agreements. Japan went so far as to charge China with violating Article IX of the OST, which stipulates agreement to “avoid … harmful contamination” in outer space.Footnote 34

As a very public demonstration of China's rapidly growing ability to challenge other countries’ unrestricted access to the space commons, the test also sparked debate among experts over China's strategic intentions in space. As a Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) assessment concluded, “not only can China threaten low Earth orbit satellites, but, by mounting the same interceptor on one of its rockets capable of lofting a satellite into geostationary orbit, all of the US communications satellites.”Footnote 35 Leading international analysts questioned the test's implications for a potential “space Pearl Harbour” and the imminence of space warfare.Footnote 36

In addition to the military debate, the test also raised questions about what it might signify for China's position regarding the scope of sovereign rights in space.Footnote 37 The OST clearly states that outer space “shall be free for exploration and use by all States without discrimination of any kind” and that “there shall be free access to all areas of celestial bodies.”Footnote 38 A number of analyses highlighted publications by Chinese experts promoting the view that, in the absence of a legal definition for outer space, China's sovereign airspace could be extended into outer space.Footnote 39 This included work by PLA Major General Cai Fengzhen 菜风震 who, with Sr. Colonel Tian Anping 田安平, had called for territorial-style vertical control of space as part of integrated military air and space operations.Footnote 40 Remarks by Bao Shixiu 鲍世修, a senior fellow at the Institute for Military Thought Studies of the PLA Academy of Military Sciences, were also given attention in this light. Bao quoted OST language affirming the principle of free access to outer space; however, his pointed criticism of what he described as the statement in the Bush administration's 2006 National Space Policy that “space systems should be guaranteed safe passage over all countries without exception”Footnote 41 was cited as evidence that influential voices in China's strategic community advocated strengthening sovereign control of outer space.Footnote 42 Also raised as a concern in this context, and seen against the background of Beijing's push for cyber sovereignty (网络主权 wangluo zhuquan) protections through the UN, was China's position on the scope of national jurisdiction over the governance of satellite transmissions or “information sovereignty,” particularly the receipt of satellite signals within Chinese territory.Footnote 43

In official documents, however, the Chinese government affirms the principle of common access to and use of outer space. These documents include successive State Council White Papers on outer space.Footnote 44 The 2006 White Paper, for example, released just a few months before China's ASAT test, states that “China's government holds that outer space is the commonwealth of all mankind, and all countries in the world enjoy the equal right to freely explore, develop, and utilize outer space and celestial bodies.” The same section in the 2011 report leaves out language on space as a commonwealth, reading instead that the “Chinese government believes that the free exploration, development and use of outer space and its celestial bodies are equal rights enjoyed by all countries in the world.” The 2016 White Paper replaces the phrase “free exploration” (自由探索 ziyou tansuo) with “peaceful exploration” (和平探索 heping tansuo), but reaffirms that “development and use of outer space and its celestial bodies are equal rights enjoyed by all countries [emphasis added] in the world.” China's 2016 Defence White Paper identifies outer space as one of the “new commanding heights of strategic competition”; however, it also articulates a commitment not only to the peaceful uses of outer space and but also to “maintain … common security.”Footnote 45

Growing Chinese scholarship on the global commons

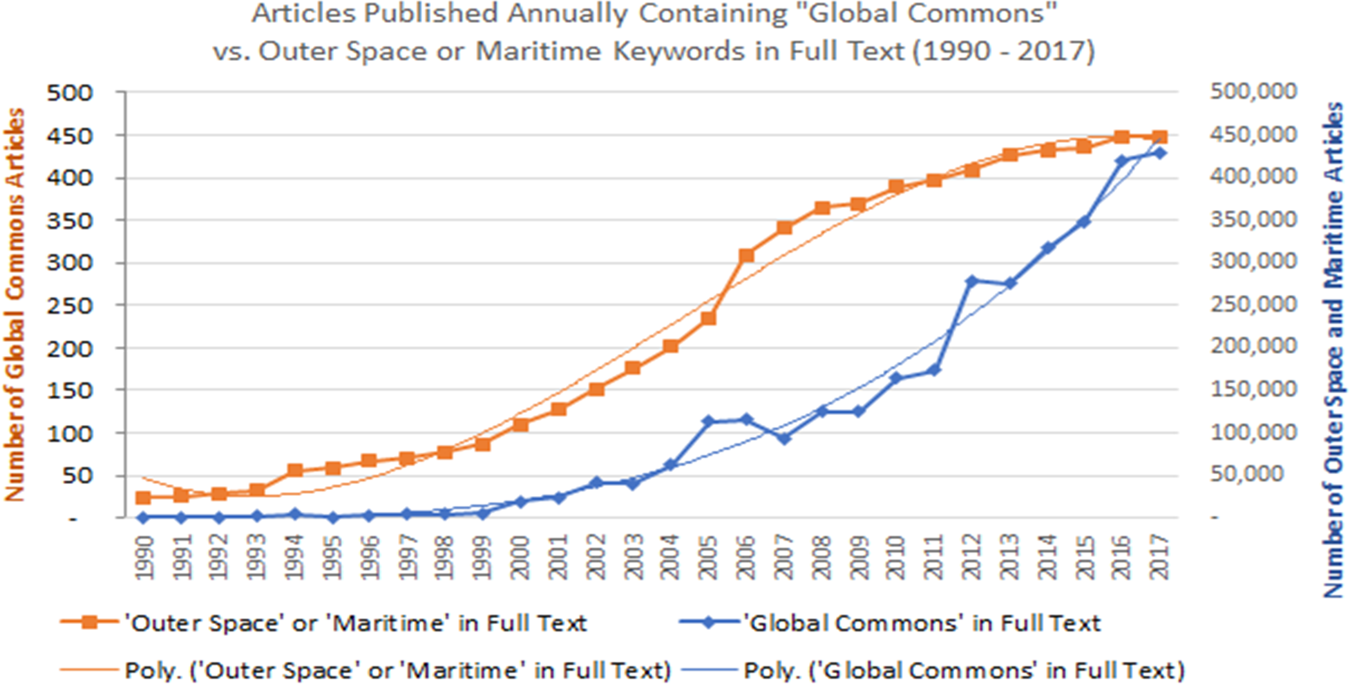

Chinese experts writing on the global commons offer insights into the thinking underlying China's behaviour in the maritime and outer space commons. Increasing numbers of publications on the global commons in the CNKI collection suggest a striking rise in academic interest in the topic in recent years, with publications increasing by a factor of 20 over the last two decades, from 20 in 2000 to more than 400 in 2017 (see Figure 1).Footnote 46 Whereas articles initially focused on the global environment – particularly in the years immediately following the 1992 UN Conference on Environment and Development, most publications are now concerned with the global commons as a factor in China's security.Footnote 47 In addition, the number of articles specifically on the maritime and outer space arenas as global commons has also been growing. A rough estimate, using the CNKI database for a full text search, suggests that of all the articles on the global commons produced in the decade from 2006 to 2016, around 25 per cent were on maritime security issues and 40 per cent addressed outer space.

Figure 1: Publication of Global Commons Articles and Outer Space and Maritime Articles

The Chinese scholars who conduct research on the global commons are affiliated with a broad array of universities and research institutes. However, most of those who are frequently cited are based at university research institutes, although a number have military affiliations. These include He Qisong 何奇松, Ma Jianying 马建英, Xia Liping 夏立平, Wang Yiwei 王义桅, Zhang Ming 张茗, and Xu Nengwu 徐能武. In the last several years, a number of scholars who historically have concentrated on other areas of research have also begun to publish substantially on the global commons. Shi Yuanhua 石源华 stands out for the number of new publications.

To date, the main centres of research on aspects of the global commons are in Shanghai. He Qisong, formerly at the School of International Studies and Public Administration of the Shanghai University of Political Science and Law and Shanghai Normal University, is now on the faculty of East China University of Political Science and Law. Ma has been affiliated with the Centre for Ocean Politics at Fudan University but is now at the Canadian Research Centre of Guangdong University of Foreign Studies. Shi is a professor in the Institute of International Studies at Fudan University, where he leads the university's Korean Studies Centre. Wang, who directs the Institute of International Affairs at Renmin University in Beijing and holds an appointment as senior fellow at Renmin's Chongyang Institute for Financial Studies (a think tank with close ties to Fu Ying 傅莹, former vice-foreign minister and chairman of the National People's Congress Foreign Affairs Committee), served as scholar-in-residence at the Chinese Mission to the European Union. He previously held faculty appointments in Shanghai at Fudan and Tongji universities. Xia, a former military officer, also served as dean of the School of Political Science and International Relations at Tongji University in Shanghai and was a fellow of the Centre for Development Studies, as well as having been general-secretary and professor at the Shanghai Institute for International Strategic Studies (SIISS). Xu is a professor in the School of Humanities and Social Sciences at the National University of Defence Technology, a university located in Changsha that is directly under China's Central Military Commission and jointly managed by the Ministry of Education and Ministry of National Defence. Zhang is at the Shanghai Academy of Social Sciences.

Also writing on maritime issues and freedom of navigation with specific reference to the global commons are several prominent legal experts from Chinese government-affiliated research institutes who regularly participate in international fora and/or appear in international media.Footnote 48 These include Zhang Haiwen 张海文 of the China Institute of Marine Affairs, a think tank under the State Oceanic Administration (SOA), and Wang Hanling 王翰灵 from the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences (CASS) under the State Council.Footnote 49 Among the Chinese experts who participate regularly in English in international debates on outer space law and governance are faculty members at the Institute of Space Law at the China University of Political Science and Law, such as Li Juqian 李居迁 and Zhang Zhenjun 张振军, as well as Li Shouping 李寿平 of the Institute of Space Law at the Beijing Institute of Technology.

Chinese perspectives on the high seas commons

Although Chinese academic publications on the maritime commons are united in their preoccupation with the use of the global commons concept by US policymakers, they reflect three distinct, although related, perspectives. The first focuses on the idea that the association of the global commons concept with the principle of freedom of navigation is a tactic used by the US to strengthen its power, particularly along, but not limited to, China's periphery. A second set of writings sees the link between the global commons concept and freedom of navigation as part of a US theory of hegemony. A third cluster sees intrinsic value in the global commons framework; however, experts in this grouping argue that the US has securitized the concept with the goal of constraining China and other emerging powers.

Scholars writing on freedom of navigation and the global commons in the context of US–China relations in East Asia draw a direct link between the US challenge to China's position on coastal states’ jurisdiction in EEZs and the use of the global commons concept in US military strategy. A number refer specifically to the 2010 US Quadrennial Defence Review Report (QDR), which stated that, “as other powers rise and as non-state actors become more powerful, U.S. interests in, and assured access to, the global commons will take on added importance.”Footnote 50 A commonly held view on the part of Chinese scholars in this group is that US advocacy for freedom of navigation within China's EEZ is an US strategy to both constrain and contain China. The title of a 2011 piece in the popular Chinese magazine Lingdao wencui (Leadership Digest) by Lu Tao 陆涛 asks: “Is United States’ ‘supremacy’ really defending the global commons?” Lu contends that the US uses the commons concept to “confuse the international public” to enable “the US to intervene in the South China Sea.”Footnote 51

Similarly, in a 2016 essay, Cao Wenzhen 曹文振 and Li Wenbin 李文斌 argue that the US is using the relatively new concept of “the global commons” to expand the idea of freedom of navigation within states’ EEZs, which international law in fact constrains.Footnote 52 The authors reference arguments made by Zhang Haiwen and summarized in her widely circulated Reference Zhang2010 essay (in English), which focuses on US and Chinese interpretations of freedom of navigation in EEZs. Entitled “Is it safeguarding the freedom of navigation or maritime hegemony of the United States? Comments on Raul (Pete) Pedrozo's article on military activities in the EEZ,” Zhang repeats the argument that EEZs are “no longer part of the high seas in nature” as the UNCLOS “unequivocally exclude[s] the EEZ from the high seas … and incorporate[s] it … into the national jurisdiction of the coastal state.” She suggests that China's view is representative of the “demands” of developing countries during the negotiations leading to the UNCLOS. Zhang concludes by remarking that the US uses the principle of freedom of navigation selectively to serve its own interests, observing that “the US military need[s] a strong imaginary enemy and take[s] China as its potential rival.”Footnote 53

Writings by Cao Shengsheng 曹升生 and Xia Yuqing 夏玉清 exemplify work arguing that the use of the global commons concept by the US Department of Defense and American think tanks in reference to maritime jurisdictional issues is part of a US “theory of American hegemony.” The authors assert that leading policymakers, such as the Obama administration's Michelle Flournoy and Kurt Campbell, utilized the concept to “accelerat[e] the pace of containing China.”Footnote 54 Scholar Wang Yiwei expresses a similar view. Wang sees the US deploying the language of the global commons to “[play] at clever hegemony” in an era of geopolitical transition. As Wang sees it, Washington's use of the “global commons” is a deliberate “sleight of hand” to evoke the language of public goods to “make emerging countries share international responsibility, while not permitting them their share of global leadership.” Further, he contends, it offers “a way for the US to develop new global rules and to find a new pretext for foreign interference.”Footnote 55 Elsewhere, Wang argues that the US has invoked the global commons concept to push back against challenges to its role as an offshore balancer in the Asia-Pacific. The US strategy includes working through ASEAN and using the coded language of the global commons to establish a linkage between economic ties and security relationships. In addition, by appealing to other countries with the idea that the US is providing global public goods as a guarantor of the security of the global commons, the US seeks to enhance its prestige and attractiveness to other countries, deliberately contrasting itself with countries like Iran in the cyber domain and China in outer space, by characterizing what the US terms China's ASAT test as a challenge to global interests.Footnote 56 In a 2014 contribution to a Center for American Progress report, Wang argues further, with reference to aircraft carriers, that the tools used by the US to project its power are not public goods and thus it is illegitimate for the US to assert that it is deploying them to secure the global commons.Footnote 57

A number of Chinese scholars focus explicitly on how the global commons idea is being used as a tool of “discourse power” by the US and its allies. In a 2012 essay, Zhang Ming describes the evolving usage of the global commons from Nobel Laureate Elinor Ostrom's common pool resource framework – a framework that suggests cooperation in a commons is possible with appropriate rules and processes – to its securitization by the Western security establishment. Zhang contends that Western powers have securitized the commons concept in the face of concerns about the impact of “emerging powers” on a complex of domains seen as vital to their own national security interests.Footnote 58

In a 2014 essay, Ren Lin 任琳 sounds a similar theme, arguing that the “public” characteristics of the global commons diminish as they are ascribed greater strategic significance. Their securitization jeopardizes the principles of open and equal access that define them and elevates the security concerns of “some countries” (read the US) over pressing collective action issues that should be given priority on the global agenda.Footnote 59

Chinese scholars writing on the maritime commons offer various prescriptions for how China should respond to the US-led “global commons strategy” (Meiguo quanqiu gongyu zhan 美国全球公域战). Describing the structure of the US system of maritime management, Xia Liping and co-author and colleague Su Ping 苏平 suggest that there are opportunities both to strengthen China's maritime role and also improve trust between the US and China in the maritime arena within such non-traditional maritime security spheres as humanitarian intervention, anti-terrorism and conflict prevention.Footnote 60 Ma Jianying takes the position that the US should be “encouraged” to set its “global commons strategy” aside through the development of a maritime security mechanism for non-traditional threats, including search and rescue, piracy, terrorist activities, smuggling and trafficking, among others. Absent this, he warns that China must proceed from a position of wariness vis à vis the US and that the strategic mistrust between the two sides will only deepen.Footnote 61

Wang Yiwei disagrees, taking the position that China must compete directly with the US in the maritime domain by transforming itself into an “ocean civilization” and promoting its own more “inclusive” vision of the global commons. Like Ma, Wang proposes that China should establish a new maritime cooperation organization (MCO) modelled on the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) but designed to “promote maritime cooperation through multiple channels” that will enable China to become an “irreplaceable leader” and “provider of public goods” in maritime Asia. Indeed, Wang suggests, the SCO and MCO could work in tandem on land and sea to promote regional cooperation.Footnote 62 Wang's proposal received considerable media attention. Several international outlets reported on it after it was mentioned in an English-language editorial in China's state-run Global Times.Footnote 63

Chinese views of outer space as a global commons

Like those who write on the maritime commons, Chinese scholars publishing on outer space as a global commons are heavily focused on US policy and its implications for both the outer space regime and China's national objectives in space. However, their shared preoccupation with US policy aside, their work falls mainly into three distinct groupings. The first considers the implications of US strategy in space for potential international (and US–China) cooperation in outer space. The second analyses China's actions in outer space, explaining them in light of weaknesses that are identified in the outer space regime, and using the shortcomings identified to make the case for international action to strengthen the regime. A third draws attention to the need for improved global space governance to mitigate threats to international security from strategic competition in outer space. All three sets of analyses identify shortcomings in the current regime for outer space governance and advocate for Beijing's proposal for a treaty on the peaceful uses of outer space.

Writings focused explicitly on US space strategy and its implications for Chinese space objectives proliferated in the late 2000s following the release of the aforementioned 2006 “New Space Policy” of the Bush administration, which explicitly promoted American space dominance, and the barrage of international criticism that followed China's ASAT test. Some experts, many based in Chinese defence universities, argued at the time that China should advance a counter-narrative against the West's criticism of Chinese space activities and wage a “media war” to promote China's interests in space.Footnote 64 However, President Barack Obama's election catalysed new discourse within civilian academic circles on ways that China might encourage the US to play a more constructive role in space governance. A 2012 analysis by Xia Liping, for example, explicitly contrasts the Bush and Obama administrations’ space policies, arguing that although the latter fails to do enough to prevent a military space race, it has the potential to help mitigate a space arms race and could be encouraged to deepen international space cooperation in outer space.Footnote 65 Similarly, Zhang Ming's Reference Zhang2012 article assessing the Obama administration's 2011 National Space Strategy commends it for being not only more “realistic and balanced” than that of his predecessor but also observes that although the US remains intent on sustaining American superiority in space, Obama's policy breaks with Bush-era unilateralism, increasing the chances for outer space cooperation.Footnote 66

Xu Nengwu and Yun Huangchang 云黄长, writing from China's National University of Defence Technology, disagree. They see far more continuity than change in US space policy from the Bush to Obama administrations. The authors contend that both administrations sought to create a multifaceted system for “strategic deterrence” to “safeguard [US] global hegemony.” In their assessment, this is a flawed ambition as the dominance of a single actor in space (hegemony) is fundamentally destabilizing for reasons that include such impacts as accelerating the weaponization of space and triggering asymmetric counter strategies by weaker states. Xu and Yun conclude that greater international cooperation is needed. They argue that the US, as the dominant space power, should exercise leadership in developing space security cooperation. However, amid “stagnating” efforts to address space-related arms control, China must do more to build “pluralism and … space interdependence.”Footnote 67 In a piece written ten months into the Trump administration, He Qisong observes that the return of US unilateralism under its “America first” doctrine, runs counter to the global “trend of space multipolarization.” He notes that approximately 70 actors, many from Asia, now operate 1,459 satellites – nearly 80 per cent of the total.Footnote 68

A second cluster of articles identifies weaknesses in existing space governance as an explanation for China's behaviour and its objectives with respect to an international treaty that will bring an end to the weaponization of space. He Qisong and Nan Lin 南琳 make an argument familiar to space governance experts that, in addition to strategic competition, it is the differences between the US and China over the definition of “peaceful uses of outer space” or what constitute space weapons that are among the key challenges to strengthening the existing regime for governing outer space.Footnote 69 Regarding the former, they argue that the US defines “peaceful use” as “non-aggressive use” – a far more expansive definition of “peaceful” than that used by China, which defines “peaceful” as “non-military.” Moreover, the inability to agree on a universally accepted definition for space weaponry – the debate centres on the status of earth-based weapons that can target satellites in orbit – is a further obstacle to preserving space as a non-militarized domain.Footnote 70

Li Juqian 李居迁 writes in legal defence of China's anti-satellite test, arguing that the test was permitted under international law, which also lacks a clear definition of “harmful contamination.” China should not, therefore, be charged with irresponsibility or liability for potential damage resulting from the test. Li makes a number of points relevant to space as a global commons and the issue of sovereign control. In enumerating the multiple flaws of the current space regime with respect to regulations on space debris, Li invokes lex ferenda, or the idea that states may establish new rules by their legal acts, a concept also used by some Chinese legal scholars with regard to maritime rights. Li also addresses the issue of property rights in space with respect to China's right under the OST to dispose of the satellite as its property. Finally, in defending the test, Li explicitly references the principle of “free access,” adding that “space is not the privilege of any single country, but for all countries to enjoy … the ‘province of all mankind’.”Footnote 71 This is a point also made in an essay by Han Xueqing 韩雪晴 and Wang Yiwei, linking common interest to the principle of open access.Footnote 72

He Qisong writes most prolifically on the topic of threats to space security related to the outer space regime. He argues that weaknesses in the existing space governance regime represent a substantial threat to space stability, principally because the absence of clear rules gives rise to destabilizing behaviour by space powers. In He's view, several issues in particular stymie progress towards improved institutional mechanisms, but the challenge of dual use technologies and the intertwining of nuclear security issues with space policy are particularly problematic. Moreover, he argues, in order to remedy the low level of transparency in space policy among space powers, a space governance regime with legally binding verification mechanisms is necessary. In the absence of such mechanisms, space activities play out as a “drama of the tragedy of the commons,” with debris cluttering lower earth orbit and threats of weaponization increasing, even as space grows more essential to global economic health.Footnote 73

Conclusions

A number of conclusions emerge from the preceding discussion. First, academic writings on the high seas commons confirm an interpretation of China's actions as the outcome of dissatisfaction with prevailing global norms with respect to states’ jurisdictional authority within EEZs. Linked to geostrategic concerns about the US presence on its periphery, China appears determined to assert its position in both deed and word, flexing its maritime muscles against foreign navies and seeking, with some success, to broaden international support for its distinct interpretation of international law.Footnote 74 China's discontent with current international norms is also apparent in proposals such as that for the MCO. The comparison drawn between the MCO and SCO is notable. In reporting on a June 2018 meeting, Chinese media contrasted the SCO with the Western-dominated G-7, arguing that the former is not a club but is “inclusive,” adding that this “Shanghai spirit” is a “new principle of international relations.”Footnote 75

Second, with respect to outer space, despite extant US dominance of the domain, Chinese elites seem to find the OST valuable, if weak. Despite concerns about the US efforts to expand its command over outer space, Chinese experts appear to see the current space environment as a genuine commons, used by a growing number of actors, in which its own expanding space capacities are able to develop fairly unrestrained. Moreover, Chinese elite observers generally share a belief that the trend towards greater numbers of space actors and parity among space powers could, if the outer space regime were strengthened, enhance stability in space.Footnote 76 Dissatisfaction with the open access principle as it applies to outer space is not a theme that emerged from this research. Chinese legal scholars affirm the open access principle in space, asserting rights of national control over space objects, but not over the space in which these objects are orbiting. While Beijing also seeks an international agreement preventing the deployment of weapons in space, Chinese experts convey relative confidence that even in the face of US opposition, China will be capable of influencing changes to the outer space regime as it continues to develop its space capabilities. Although not a point explicitly addressed by Chinese scholars, this relatively sanguine view of outer space law, which stands in such sharp contrast to Chinese attitudes towards the maritime regime, may reflect different views of the two regimes, one of which was established through the United Nations only in recent decades and the other still undergirded by customary law.

If China behaves as a situational power with regard to the universal access principle that defines the global commons, what are the implications? If, indeed, China's orientation and attendant policies towards existing regimes – whether legal revisionism and assertive actions or fundamental support – depend upon Beijing's assessment of how a given regime relates to its national goals and ambitions, this argues for caution with regard to blanket characterizations of China as revisionist vis à vis current global rules and norms. More comparative and contextualized studies of China's engagement with global regimes, including research that goes well beyond this study in interrogating the methodological challenges inherent in seeking to understand the perspectives shaping Chinese foreign policy, may provide more accurate assessments of China's orientation towards established systems for managing global issues. Such research may provide greater insights into the sources of Chinese conduct and suggest new pathways through which to secure Chinese compliance or cooperation. This is not an insignificant undertaking as the risk of conflict in the global commons between the US and China intensifies.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to David Lampton, Michael Chase, Adam Lee, Bruce MacDonald, Jeffrey Pryce and the anonymous reviewers for their invaluable feedback. My thanks to Cory Combs, Miaosu Li, Woqing Wang and Siyu Zhou for their excellent research assistance.

Biographical note

Carla P. FREEMAN is associate research professor of China studies at Johns Hopkins School of Advanced International Studies (SAIS) and the director of the SAIS Foreign Policy Institute and co-director of the Emerging Global Governance project. Most of her research explores the relationship between China's domestic and foreign policy. She is working on a book on China and the global commons.