Between 28 September and 17 December 2014, Hong Kong's Umbrella Movement took the world by surprise and placed the semi-autonomous city in the limelight once more following its handover from the United Kingdom to the People's Republic of China. According to two university polls, 18 to 20 per cent of the local population, or 1.3 to 1.45 million people, participated in the movement – a participation rate that had elicited regime changes in places such as Georgia, Ukraine, Egypt and Tunisia.Footnote 1 While the Umbrella Movement failed to result in a democratic transition or political concessions, its scale and resilience made it one of the most spectacular revolutionary moments of our time.Footnote 2

Despite the duration of the occupation and the mass participation, I argue that the Umbrella Movement is a particular manifestation of a new wave of bottom-up activism in post-colonial Hong Kong, where the hybrid regime is characterized by civil liberties, an independent judiciary and evolving electoral politics, but also corporatist domination and a resourceful local government backed by an authoritarian sovereign. This paper aims to examine the diffusion of activism within this context through the lens of eventful analysis and political regime. It traces the dynamics of a historic cycle of protests in post-colonial Hong Kong which mobilized new actors and triggered transgressive repertoires that led to the Umbrella Movement. As William Sewell proposes, events are “sequences of occurrences that result in transformations of structures” by “constituting and empowering new groups of actors or by re-empowering existing groups in new ways.” However, while events produce a surprising break from routine practices, “most ruptures are [also] neutralized and reabsorbed into the pre-existing structures in one way or the other.”Footnote 3 The politics of time reveal how critical junctures have translated macro-structures into political awareness and shaped the path of collective action.Footnote 4

In this light, it is necessary to look beyond the driving forces of this wave of activism and examine also its underlying structure and contingent events. Charles Tilly notes that while activists play a crucial role in selecting their repertoires, state responses are vital in shaping their options.Footnote 5 Mobilization is not the only response to dissent; regimes also demobilize and counter-mobilize in the face of challenges. Graeme Robertson further reveals that hybrid regimes are many, varied and changing, and that they create a hybridity of repertoires.Footnote 6 Thus, Hong Kong's new activism is pertinent for recognizing the evolving pattern of protest against resilient authoritarianism during global “democratic recession,”Footnote 7 and it serves as a timely response to the growing literature on how protests are managed in hybrid regimes and whether street politics have become an integral part of competitive authoritarianism.Footnote 8

Different Approaches to Hong Kong's Activism

Existing literature has addressed the prevalence of political activism in Hong Kong from two perspectives. On the one hand, such activism counters the notion that Hong Kong is an apathetic society dominated by a transient mentality that minimizes or absorbs dissent, or keeps it latent through the “administrative absorption of politics.”Footnote 9 This classical understanding of state–society relations has been contested by studies that reveal the robustness of political participation and the extent of policy changes prompted by riots and strikes during the colonial era.Footnote 10 That said, those protests were largely imported or organized; that is, they were either endorsed by the Communist or Nationalist regimes, or initiated by trade unions. The colonial regime contained these organized challenges to reconsolidate its authority and legitimacy. It simultaneously empowered civil society to provide social services for the grassroots and co-opted reputable non-governmental organizations (NGOs) by correlating their thrift with state recognition and funding.Footnote 11 Consequently, protests in the colonial era primarily served as pressure-group politics and advanced issue-specific and functional claims, leaving broader political agendas unscathed.Footnote 12

On the other hand, in the post-colonial era, activism is largely considered to be an indicator of governance crises or structural grievances. First, the political opportunities structure approach emphasizes the institutional weaknesses of Hong Kong's new regime. Siu-kai Lau and Hsin-Chi Kuan suggest that unfledged party politics have encouraged unconventional means of combining and articulating the interests of the ruler and the ruled.Footnote 13 Separately, Joseph Cheng, Ming Sing and Ray Yep point to Hong Kong's pseudo-democracy and its successive administrations’ unwillingness, or incapacity, to promote democratization, resolve political decay and protect existing rights and freedoms as the causes of public outcry.Footnote 14 Second, the relative deprivation approach uncovers the escalation of grievances and cleavages in the post-colonial era. Kun Eng Kuah-Pearce and Gilles Guiheux consider the city's growing inequality to be the instigator of the anti-globalization movement.Footnote 15 Wing-sang Law regards the handover as a re-colonization process, in which the new regime continues to endorse the collaborative structure and crony capitalism inherited from the old regime.Footnote 16 Both Ngok Ma and Alvin So associate the swell of contention with the cleavages of a post-industrial society in the absence of democratic institutions in which authority is questioned, order is negated, and the downsides of party politics are amassed but its merits are overdue.Footnote 17

These studies provide fruitful surveys and contextual analyses of Hong Kong's multiple transitions since the handover. They establish and consolidate the notions of an obsolete political system and a civil society in self-defence mode, indicating that the struggle for accountable and democratic government and the duty to defend/preserve existing rights and freedoms are reasons to voice dissenting opinions and rebel. However, their subject of inquiry determines that their focus is centred on organized protests or specific rallies, whereas the characteristics of bottom-up activism and its diffusion mechanisms are categorically omitted. The timeframe of these studies also neglects the profound changes in actors, repertoire and claims in the recent wave of activism. Contentious politics are seldom regarded as an explanatory or intervening variable.Footnote 18

An interactive approach transcending political opportunities and relative deprivation to give microscopic attention to the dynamics of protests and regime reactions is necessary.Footnote 19 This paper contains three parts. First, it examines the relationships between Hong Kong's hybrid regime and its ordering of organized protests, revealing that both the establishment and opposition are conducive to the creation of a “nascent movement society.”Footnote 20 Second, it traces the diffusion mechanisms through the critical events of 2003 through to 2014. This time-series analysis shows how grievances are collectively recognized and opportunities are steadily explored in the course of regime reconfiguration and the “public staging” of bottom-up activism.Footnote 21 Third, it surveys why the regime adapted a hybridity of elite cohesion, targeted reprisal and counter-movements to manage street politics, and how this approach shielded the regime but sparked the Umbrella Movement. While regimes structure repertoires, the relationships between a regime's openness and a protest's scale are non-linear. Correspondingly, political awakening and collective action do not necessarily spur democratic prospects. Instead, I argue that enduring instability without democratization is an increasingly common trend in hybrid regimes encountering mass protests.

Methods and Data

Pertinent data were collected via several means. First, I collected the data for six critical events that drew more than 300 participants, involved a range of NGOs, warranted responses from the highest authority or induced policy changes. These criteria comprise the scale, subject and outcome/object of contention, respectively. The object criterion excludes strikes that mainly targeted private firms. A duration criterion, that the event lasted for at least one week, was applied to distinguish critical events from organized protests. Second, I conducted 21 semi-structured interviews with leading activists between July 2012 and September 2014. These included four veteran activists, 12 event organizers, and six elected politicians who led or brokered protests. Third, I undertook participant observation of four events and used interviews and media footage to supplement accounts of the two events that were omitted. Fourth, I conducted a survey (n = 1,681) of the occupied areas of Admiralty, Mongkok and Causeway Bay between 20 and 26 October 2014. Trained volunteers were deployed to pick samples randomly after walking a fixed number of steps on an assigned route. The study period begins in 1997, when the hybrid regime was instated, covers a series of events and regime responses that unfolded after the 1 July rally in 2003, and ends in 2014, when the new activism evolved into the Umbrella Movement.

Protest Structure under the Hybrid Regime

Following on from the studies on competitive authoritarianism, this paper defines regime as a governing coalition consisting of the state, power groups and political elites who “wield regular and substantial influence over a country's political system.”Footnote 22 Compared with other hybrid regimes, Hong Kong's autonomous status ensures multi-level and intertwined configurations, comprising Beijing's Central People's Government (CPG), the Special Administrative Region Government (SARG) and pro-regime elites who pledge allegiance to both central and local authorities. This hybridity has shaped the cycle of activism and regime reactions.

Institutional foundations for regulated protests

The hybrid regime in post-colonial Hong Kong is characterized by liberal-democratic and corporatist-oligarchic elements. With Hong Kong's future decided by the Sino-British Joint Declaration in 1984, the colonial regime began to introduce democratic reforms. Popular elections were introduced in 1982 in the District Boards and extended to the Legislative Council (Legco) in 1988. The Hong Kong Bill of Rights (1991) was incorporated into the legal system to protect human rights, superseding all conflicting laws. Democratic reforms, along with the tradition of rule of law, have since been put in place to protect civil liberties and ensure the freedoms of speech and assembly. Local citizens have adapted to these changes by forming NGOs, voicing dissenting opinions, and promoting pluralistic values without fear of state coercion or retaliation.Footnote 23

The Basic Law, Hong Kong's mini-constitution, stipulates that the executive and legislative branches are subjected to different electoral systems and diverse electorates. The Chief Executive (CE) is elected by an election committee consisting of a narrow franchise of politicians, conglomerates and professions. The Legco is divided into geographical and functional constituencies, of which the share of popularly elected seats has steadily increased from 33 per cent in 1998 to 50 per cent in 2009; the remaining seats are allocated to business associations and professional unions. The result of these intricate electoral systems is an executive–legislative deadlock, with a pro-regime majority guaranteed in the legislature while the accountability of lawmakers is fragmented and spread among their diverse electorates.Footnote 24

The CE is prohibited from having any party affiliation, which effectively restricts the formation of a formal ruling coalition. To ensure enduring support in the Legco, the government offers selective incentives, such as membership in advisory and statuary bodies or public projects, to pro-regime elites. Despite these incentives, the institutional setting has motivated the establishmentarians or pro-regime lawmakers (qinjianzhi pai 亲建制派) to act as if they were the opposition. They organize protests at government buildings on a daily basis in order to fulfil election promises, prompt policy changes or profit from unpopular officials.

Based on a similar logic but aimed at a different audience, the opposition – or pan-democrats (fanminzhu pai 泛民主派) – which consistently gains more popular votes and yet is institutionalized as a minority in the Legco, also considers the periodic mobilization of the masses to be an effective means of bolstering its leverage in the face of a collaborative ruling coalition that is closed to it. Together, these features constitute the hybridity of Hong Kong's regime and form the foundations and boundaries of street politics. Hong Kong's “civil oligarchy” is thus cohesive enough to select concessions and resist changes but lacks the tools to contain protests, let alone suppress them.Footnote 25

The logic and trend of protests

Protest is a broad and often vague concept that can refer to all sorts of collective actions. Despite the familiarity of the concept, what a protest includes, excludes and implies has not been clearly defined. Sydney Tarrow recently emphasized the utility of contentious words, showing how their construction can shape the appeal and dictate the sequence of activism. The changing variety of contentious words is indeed closely related to the transformation of activism in Hong Kong.Footnote 26

Before 2006, the meaning of “protest” in Hong Kong was mainly confined to demonstrations (youxing 游行) and rallies (jihui 集会). Political parties, trade unions and NGOs organized protests on a daily basis. Although their agendas varied, the protests were consistently limited to one or several dozen people, most of whom were politicians, unionists, and their friends or assistants. On many occasions, establishmentarians recruited temporary demonstrators or supported protestors with meals and allowances.Footnote 27 Regardless of the camp, the slogans and strategies used during protests were typically designed and standardized by experts. This practice indicates the absorption of street protest into electoral politics, in which organized elites articulate and express public interests through contentious yet controlled means. This inevitably makes protests contrived or calculated, contradicting the impression that they should be genuine or spontaneous.

In Hong Kong, massive rallies, although less frequent, are an integral part of the periodic protests. Annual rallies include the 1 July rally and the 4 June vigil, which began in 1989 and 1997, respectively, and which attract tens to hundreds of thousands of participants each year. The historic 1 July rally in 2003 is widely considered to be a watershed event, when more than half a million citizens protested against a proposed national security law that served as a loyalty pledge to the new sovereign. In the face of authoritarian encroachment, civil society resisted and defended its realm. Yet, the object of contention largely switched to the SARG rather than the CPG, as the former was regarded as having a dual loyalty to Beijing and to Hong Kong, and hence was a legitimate member of the defence team.

Table 1 presents the trend of protests over the past decade. “Legal processions” refers to public meetings of more than 50 people or public processions of more than 30 people that were approved by the police under the Public Order Ordinance.Footnote 28 There were 51,915 approved applications, out of a total of 51,946, between July 1997 and September 2012, or an average of ten protests of that scale each day.Footnote 29 The number of these protests increased from 1,974 events in 2004 to 6,818 in 2014. While the 1 July 2003 rally is widely considered to be a critical juncture that cast the strength of local civil society, the data suggest that 2006–2007 was another point when the number of collective actions increased rapidly. Since then, the annual change in processions is highly correlated with the timing of critical events. Moreover, the percentage of processions that ended with a prosecution increased tenfold in one decade. The number of prosecutions resulting from unlawful assembly or assaulting a police officer, which shows a clear intention of civil disobedience (gongmin kangming 公民抗命), has also increased steadily over the years.

Table 1: Protest Trend in Hong Kong, 2004–2014

Source: Hong Kong Legislative Council 2013; Hong Kong Security Bureau 2016.

Nascent movement society

Organized protest in Hong Kong is vibrant and popular, and serves as an acceptable means through which politicians and activists can exert pressure on the hybrid regime. It effectively combines street politics with electoral politics and extends the realm of contention towards normalization. Characterized by similar means, agencies and courses of action, organized protest favours the following dominant strategies: for the pan-democrats, whose priority it is to sustain morale in light of the ups and downs of the protest cycle: lead and disperse the masses when necessary; for the protestors, for whom participation matters only if it aligns with electoral politics: march during pre-established critical moments; for the SAR government: wait and let the crowds disperse – all protests are eventually containable and confrontation is both costly and unnecessary.

Certain preordained repertoires endure. Social movement organizations (SMOs) and political parties regularly plan rallies and demonstrations and carefully conduct them within legal boundaries to avoid clashes with police. Participants engage in pre-set routines and rituals that reduce their participation to merely being part of a headcount. The main objective is to increase the pan-democrats’ leverage to solicit concessions from the authorities. Thus, whereas contentious actions have become more frequent, sizeable and politicized, the SAR government withstands them by maintaining elite cohesion and leveraging legal interventions.

This has resulted in a nascent yet impeded movement society. Certainly, civil liberties, the rule of law and electoral politics have cemented the co-existence of a highly mobilized civil society and regulated protests. Yet, in contrast to liberal democracy, from which the concept developed, street politics have not been fully institutionalized into the hybrid regime to allow effective checks and balances by the opposition, nor have the major players in the regime accepted its normalization and proliferation without the fear that it could weaken the regime's legitimacy and hamper policymaking. Thus, whereas elected politicians and proactive citizens consider street politics a necessary adjunct to conventional politics in the hybrid regime, the CPG continues to perceive protests as signs of disloyalty, inferring that the “people's hearts and minds have not returned” (renxin weihuigui 人心未回归).Footnote 30

Regime reconfiguration backfires

The multi-level configuration of the hybrid regime entails viewing street politics as a matter of governance crisis and national security. The strength and intensity of organized protests, albeit contained, alarmed the CPG into reconfiguring the hybrid regime, which repeatedly backfired. By “reconfiguration,” I refer to a process of economic integration, institutional adjustments and identity construction that aims to subordinate local society to its authoritarian sovereign. By “backfiring,” I refer to the critical events during which protesters challenged the hybrid regime for ignoring the public will and failing to uphold self-autonomy.Footnote 31

The reconfiguration began right after the 1 July rallies in 2003 and 2004 that led to the withdrawal of national security legislation and the ousting of the first CE, Tung Chee-hwa 董建華. Jasper Tsang 曾鈺成, a pro-regime elite and president of Legco, admitted that 2003 was the turning point that prompted the CPG to change its policy from “non-intervention” (buganyu 不干预) to “proaction” (youzuowei 有作为).Footnote 32 One indicator of this change is that a Politburo Standing Committee member has since then chaired the Central Coordination Group for Hong Kong and Macau Affairs.

Specifically, the CPG expanded its control of economic, cultural and political frontiers. Closer economic and regional ties between Hong Kong and the mainland were actively promoted through trade pacts (for example, the CEPA) and infrastructural projects (for example, the Hong Kong–Guangzhou Express Rail Link) to increase trade, investment and people flows. Government–business collaboration intensified. By granting business elites direct access to the CPG, regime stability was bolstered by capitalist cronyism and its trappings, including growing favouritism, decreasing social mobility and entrenched inequalities.Footnote 33 Culturally, in response to former President Hu Jintao's 胡锦涛 speeches on the relationship between edification and patriotism, former CE Donald Tsang 曾蔭權 introduced the idea of “New Hongkongers” in his policy address to encourage patriotic subjects who view the city from a national perspective. This approach materialized into the highly controversial national education curriculum in 2012.Footnote 34 Politically, the CPG's role in the regime expanded and surfaced. A ranking officer in the Liaison Office of the CPG published an article in 2008 in Study Times, a Central Party School newspaper, calling for the establishment of a “second ruling office” (dierzhi guanzhiduiwu 第二支管治队伍) to assist the SARG fully, openly and legally.Footnote 35 Owing to their abundant resources and grassroots infiltration, the establishmentarians steadily increased their share of the votes against the pan-democrats in successive Legco elections, climbing from a share of 34 per cent in 2004 to 45 per cent in 2012.Footnote 36

The reconfigurations contained a paradox: as the reach of the central government expanded, the authority of the local government weakened. This change neither reduced the protests nor absorbed dissent into the political system to enhance stability. Instead, it was evident that conventional politics were unable to defend existing rights and freedoms and “freeze” preordained central–local relations. Furthermore, when it became clear who made the final decisions, the object of contention inevitably shifted from the SARG to the CPG. A series of critical events synchronizing pro-heritage, anti-hegemonic and anti-integration claims both expounded and defied the legitimacy of the regime.

The Evolution of Bottom-Up Activism

Between 2006 and mid-2014, a total of six critical events occurred that met the aforementioned criteria. They included actions to preserve the Star Ferry Pier in 2006 and preserve the Queen's Pier in 2007 (pro-piers), to oppose the Guangzhou–Hong Kong express railway link in 2009–2010 (anti-railway), to oppose the national education curriculum in 2012 (anti-curriculum), to protest the North-East New Territories Development Plan in 2012–2014 (anti-development), and to call for the re-issue of free-to-air television licences in 2013 (pro-licence). Although official figures standardize the estimates among different events, the police only release headcounts for specific episodes, thereby hindering comparisons within an event. In contrast, organizers’ figures are always highlighted in the mass and social media and serve as a catalyst for further mobilization. This constructed reality, which aligns with our dynamic orientation, instead justifies the figures reported by the organizers.Footnote 37

A scale shift in participation

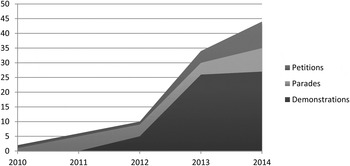

Figure 1 shows the scale shift in participation from one event to another. The number of participants increased from a maximum of 450 in the pro-piers events in 2006–2007, to 8,500 in the anti-railway events in 2009–2010; in other words, there was a 19-fold increase in event size in approximately two years. That size reached 120,000 in the anti-curriculum event in 2012 and the pro-licence event in 2013, which reflects an additional 14-fold increase in participation over two years. The only exception to the trend was the anti-development protest in 2012, for which the maximum number of protestors declined. This was primarily because the event emerged at the early stage of a policy proposal when the threat was distant and conventional procedures were available. When the situation changed in June 2014, protestors lay siege to Legco and confronted legislators.

Figure 1: Scale and Resilience of Critical Events in Hong Kong, 2006–2014

The pace and source of mobilization further distinguished the new activism. Unlike past rallies that required months of agenda setting, press briefings and mass mobilization, these events bypassed these steps. While personal ties continued to connect the event organizers, participants became involved spontaneously and took only weeks or even days to rally. For example, the national education curriculum prompted the formation of Parents’ Concern and Scholarism (xuemin sichao 学民思潮) on 17 July 2012, and a fortnight later, 90,000 people marched to the government headquarters. A founder of Scholarism recalled that all of its 300-plus members were strangers who were rallied through Facebook and WhatsApp.Footnote 38 On 15 October 2013, two members of Left 21 (zuoyi nianyi 左翼廿一) created a Facebook page to contest the government's decision to reject a highly competitive – and relatively critical – television operator's application for free-to-air television licences. In less than 24 hours, the page received more than 440,000 “Likes,” and it ranked number five among all Facebook pages in Hong Kong as of 15 March 2014.Footnote 39 The grievances on social media were immediately converted into collective action, and 120,000 people were mobilized to occupy the government headquarters three days later.

Additionally, resilient protest and decentralized organization reinforced each other. The six events had, on average, 67 days of contentious episodes each and each event involved multiple peaks of mobilization. The longest event lasted 122 days, and the shortest event lasted 43 days. Compared with organized protests that typically last for minutes or hours, the contentious episodes of these critical events were greatly extended. Tens to hundreds of hard-core activists secured the field between the peaks of each event, waiting for the masses to rally after work or on weekends. To sustain the organized occupations, the protesters had to resolve many logistical issues, such as soliciting donations, recruiting volunteers, and distributing goods and services. New and young activists, who had no party affiliations or only loose connections to grassroots communities, emerged as initiators or informal leaders in the field. These robust interactions cemented the horizontal, self-mobilized image of Hong Kong's activism established after the 2003 rally that downplayed the roles of traditional SMOs and political parties.

However, a decentralized protest structure must be distinguished from disorganization. Veteran activists’ networks and the representations of pan-democrats in the Legco were essential to escalate protests. Second, new civic groups emerged from the events. Along with Scholarism and Left 21, other examples include Local Action (bentu xingdong 本土行动), the Land Justice League (tudi zhengyi lianmeng 土地正义联盟), and Civic Passion (rexue gongmin 热血公民). These leading new SMOs established propaganda outlets (for instance, InMedia, Dash and Passion Times) to connect with their supporters. Despite the reorganization, these SMOs mainly succeeded in constructing a unique identity and building personal trust among activists for mass mobilization rather than forming a hierarchical structure to enable coordinated strategies. Many young activists, however, considered the dispersed and decentralized organizational form to be fairly conducive to combating the regime's strategy of co-optation and containment.Footnote 40 Consequently, despite the vigour of the civil society and its capacity to mobilize huge numbers, its lack of a sophisticated organizational structure remains problematic.

Public staging of the propositions of contention

Another defining feature of the new activism is its public staging of events, involving direct action and symbolic performance. Table 2 summarizes the repertoires of the six critical events. It shows that while occupation (zhanglin 占领) or laying siege to a building (baowei 包围) has become a standard action, creative yet non-violent performances relevant to specific events are also increasingly common. Despite widespread contention, the pre-existing cleavage between establishmentarians and pan-democrats has endured, and the state has rarely conceded to protest claims. What factors diffused the new activism despite its inability to win tangible concessions? In what ways have these conjunctures created ruptures in the regime structure, needled political awareness and normalized collective action?

Table 2: Critical Events in Hong Kong

Source: Author's synthesis.

Occupation is central to the new activism. This process disrupts the established order by disrupting traffic, work patterns and the very idea of ordinariness. David Harvey regards cities not only as centres of capital accumulation but also as theatres where grievances about and open resistance to neoliberalism are contemplated.Footnote 41 Jeffery Juris states that social media permit “logics of aggregation” in a public space to assemble the masses and sustain a decentralized protest.Footnote 42 Three youth activists who initiated the city's first and longest occupation admitted that they consciously emulated the direct actions of South Korean farmers at the World Trade Organization's Sixth Ministerial Conference in Hong Kong in 2005 with the view that open, collective resistance is a means of contesting a regime that is closed to them. While these progressive origins and international links framed the occupation, the regime context was vital:

The idea of reclaiming our public space emerged long ago. It was practised at Star Ferry Pier but was short lived. Lack of surprise was one reason, and [a lack of] persistence another. On the eve of 26 April 2007, we decided to replicate the direct action. A dozen of us marched towards Queen's Pier, which was already blockaded, waiting to be demolished. The guards tried to stop us, and the police arrived within minutes. When we thought that our action would fail, the police suddenly retreated and secured a perimeter.

Different sorts of people moved into it [the perimeter], not only activists and students but writers, architects, artists and academics. We organized talks, concerts and hunger strikes, and shared our ideas, food and tents. That perimeter produced the city's most visible public space in the following months; the period was itself monumental.Footnote 43

This first-hand account reveals how unprepared the hybrid regime was to manage the shift in repertoires. These direct actions inflicted costs on the state and showcased the protestors’ sacrifices.Footnote 44 During the annual rallies, which rightfully earned the reputation of being peaceful, rational and non-violent (helifei 和理非), millions of protestors marched on 15 consecutive years, with only a few dozen assaults and not a single robbery; in contrast, the critical events of the study period always involved occupations, sieges, hunger strikes or blockades. The police reacted by increasing their numbers, repeatedly using violence and leading charges against the protestors; however, these actions did not smother popular mobilization. On 2 August 2007, when the police finally moved in to clear the occupation from the piers, 17 activists chained themselves together to illustrate how civil disobedience is justified in the face of state coercion. In January 2011, more than 80 activists and villagers blockaded workers and bulldozers to prevent them from demolishing village buildings. Starting with relatively controversial issues and evolving through confrontation and sacrifice, these spectacular events mobilized a segment of society which would not otherwise listen to, endorse or participate in unsanctioned or illegal assemblies.

Direct action has also involved staging various symbolic performances related to the themes of each event. Heritage tours were held to monumentalize the Star Ferry and Queen's piers as a collective memory of the anti-colonial resistance and grassroots mobilizations dating back to the 1960s and 1970s. Imitating the “prostrating walk” of Buddhist pilgrims, protestors held a parcel of rice, kneeled, and bowed across five districts of Hong Kong to show their affection for the city and its indigenous community and to express their disapproval of the express rail link megaproject. Three subsequent events, directed towards the SARG and pro-regime elites, witnessed a dramatic increase in participation and confrontation. A student strike in the secondary schools, the likes of which had not occurred for more than three decades, was almost launched to protest against the implementation of the “brainwashing” national education curriculum. A bazaar was set up in front of the government headquarters to sell the organic and home-grown produce that would be sidelined with the implementation of the extensive North-East Development Plan. Satirical sketches were freely and openly performed in front of the government headquarters mocking the government's attempt to censor the free-to-air television operators.

These series of events do not just illustrate the rupture created by a dozen committed activists; they are also an appraisal of the organized protests led by SMOs and political parties. Frustrated by the organized nature of sanctioned protest in Hong Kong, young activists who used to mobilize the 1 July rally sought alternative channels through which to vent their discontent:

The 1 July rally has become routinized. Constrained by precedent, we felt compelled to brief the authorities on detailed actions and even help the police to disperse the crowd at the end-point. These expectations are absurd. How can we denounce the regime and then work with it with ease? Isn't protest supposed to be radical, or at least unpredictable?Footnote 45

Organized protest was denounced as ritualistic and impotent. When people march and then go home, their behaviour is highly predictable and expressive. Without coercion, or the threat of it, the government will respond to periodic outcries but is not forced into making any real changes. This effectively creates a proposition of contention that prioritizes empowerment (chongquan 充权) along with soliciting concessions.Footnote 46 While these two aims can reinforce each other, they breed tension. For the rearguard faction, the fight for democracy is partly a pretext for securing a high level of autonomy. When the chance to advance universal suffrage diminished following the CPG's reconfiguration of the regime in Hong Kong, the formation of a pre-emptive line of defence was advocated. The vanguard faction, however, stresses that perpetual mobilization is an effective means of spurring protestors to transcend the collaborative system inherited from the old regime and to invent a new order and identity. Despite their different orientations, these two factions share their resources in defiance of the regime's legitimacy, making direct action a defining feature of Hong Kong's new activism.

Conditions for re-experience and diffusion

Although these propositions have steadily transformed the boundaries of contention, why were illegal actions tolerated in the first place? According to several politicians, the highest authority ordered the sudden retreat of the police.Footnote 47 Amidst the regime reconfiguration, former CE Donald Tsang was seeking re-election in 2007. A colonially trained bureaucrat who accidentally became CE after his predecessor was ousted after the 1 July rallies, Tsang was eager to present himself as a native son of Hong Kong and a seasoned bureaucrat who appreciated the city's core values and who had the skills to secure them. This interplay between rupture and adaptation illustrates the power of contingent events: while the 1 July rallies empowered NGOs, they fostered tension between preordained and bottom-up activism, and while direct action caused systemic regime reconfiguration, a temporary reconciliation favouring a technocratic administration surfaced. Contingency, however, is structured by the regime's hybridity, in which the interests of the CPG and SARG sometime diverge and electoral outcomes matter, thereby providing opportunities to be explored.

Moreover, civil liberties enhance the diffusion of direct actions. While the pro-regime tycoons’ near-monopoly of the mass media has encouraged self-censorship, they are constrained by a market-oriented model and a corps of front-line journalists.Footnote 48 Their 24-hour news channels, for example, simply cannot afford to ignore events that last for months, and their editors and reporters instantly gave a voice to the protestors once the gatekeepers were off-duty. Working alongside the mass media is citizen journalism, which emphasizes street-level perceptions, native accounts and alternative voices. The propaganda outlets of the new SMOs edited protest footage to mobilize the masses and coordinate protest actions. Initially, people who shared similar stances or values were grouped together. Soon after, interactive sites such as HouseNews and VJMedia attracted new writers and readers and further blurred the boundaries between objective observers and passionate participants. Derivative works also benefited from the abundant footage, and staged acts of resistance, including seminars, exhibitions, songs, books and cartoons, were promoted and circulated between and after the events.

These alterative re-experiences aided instant sharing, in-depth analysis and everyday resistance, thereby expanding the reach and durability of the contentious episodes. Internet traffic data confirmed that traffic increased after the escalation of the anti-curriculum, pro-licence and anti-development events. As of 15 March 2014, the most popular alternative news outlet, HouseNews, ranked number 95 in Hong Kong and number 18,693 globally, rising 7,326 places in three months.Footnote 49 When the patron of HouseNews closed the site in July 2014, citing fear, concerns from businesses in China and advertisement boycotts as the reasons for the closure, the vacuum was instantly filled.Footnote 50 Writers soon created new blogs, and InMedia, Dash and the more radical VJMedia and Passion Times absorbed the HouseNews’ readership. While activists were saddened by the closure of HouseNews, they were also provoked by it. One interviewee considered its closure as “the end of constructive dialogue”; another called it “the proliferation of guerrilla warfare” (biandikaihua 遍地开花).Footnote 51

Hong Kong's electoral politics have also begun to interact with street politics, although the lawmakers have steadily devolved from organizers to followers. Figure 3 shows that parliamentary hearings and bipartisan splits have become the usual response to critical events. Nearly every pan-democrat raised protestors’ concerns at Legco council and committee meetings to gratify their supporters and put pressure on the regime. Radical pan-democrats have pushed their colleagues to endorse filibusters since the anti-railway event in 2009 and to use resignations in order to call a five-constituency referendum in 2010. The establishmentarians reacted by disregarding the usual procedure of alternating committee chairs with pan-democrats and by tightening the deliberation procedure. Legco has evolved into another theatre of action, where the debates are split between pro-people and pro-regime camps. Despite these reactions, the pan-democrats were barely able to claw back their leadership position. In fact, in the 2010 civil referendum only two-thirds of their traditional supporters were mobilized to vote, causing an internal split. When the opposition's inability to rally its supporters was exposed, it lost its mandate to perform backroom deals and its members began to function as delegates rather than as representatives.

While the six events often failed to gain concessions, their public staging enhanced the collective recognition that the accumulated grievances are embedded in the pseudo-democratic, corporatist regime. Subjected to the discrepancies between protest claims and popularized messages, a vague but holistic framing of “local discourse” (bentu lunshu 本土论述), comprising anti-real estate hegemony (dichan baquan 地产霸权) and pro-collective memory (jitihuiyi 集体回忆), was galvanized. This framing diffused into an eclectic range of central–local tensions sparked by the influx of mainland tourists and capital and the resulting contentions about real estate, medical and education services, and daily necessities. Similar to the trajectory in other hybrid regimes, such as those of Thailand and Russia, wildcat protests, populist policies and state-sponsored groups used these tensions to their advantage and flourished. However, Hong Kong's civil liberties, rule of law and global exposure make it unique and set the boundaries for the actions of its regime.

Reactive Reponses and Widening Contention

Experience of the multiple transformative events has shaped the hybrid regime's reactions. Anticipating that cyclic mass mobilization could pose a threat to the regime's legitimacy, and so framing the emerging “localist protest” as a matter of national security, the hybrid regime, and in particular the hardliners in the current administration, has adapted a range of demobilization and counter-mobilization strategies, each escalated to new frontiers and covering a hybridity of macro-, meso- and micro-level mechanisms to manage street politics.

Counter-mobilization without demobilization

The CPG has applied a united front strategy (tongzhan 统战) to expand the pro-regime camp since the late colonial era with the aim of ensuring a smooth regime transition. The focus of co-optation was altered in the post-colonial era to enhance regime stability. For example, after the 2003 rally, James Tien 田北俊, the former leader of the Liberal Party, withdrew his support for the national security bill, which led to the bill being halted and former CE Tung Chee-hwa being ousted. Punishment was swiftly delivered. In the 2008 elections, half of the Liberal Party's Legco members left to form a new party to promote business interests. While the Liberal Party lost all its seats in its geographical constituencies after the CPG's grassroots machine withdrew its support, it survived via the functional constituencies.Footnote 52 These outcomes imply that these swing politicians cannot be easily manipulated, nor can their power base be fully removed in the intertwined hybrid regime. Instead, they are co-opted by representation in and access to the SARG and the CPG. Likewise, when Tien attempted to defect during the Umbrella Movement, he was immediately expelled from the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference but was seen as a member of the “patriotic force.” Because elite support is essential in times of crisis, punishment must be severe enough to generate a credible threat but not trigger a snowball defection. This macro-level management has convinced political elites that their best interests lie in aligning with the incumbents instead of working against them.Footnote 53 Consequently, elite cohesion has limited political opportunities and concessions.

Targeted reprisal is a micro-level reaction. During the course of the six events, the nature of reprisals shifted, from arresting stalwart volunteers to prosecuting protest leaders. Two middle-aged volunteers were prosecuted and imprisoned for assaults during the pro-piers events; seven villagers were prosecuted and fined for their blockade in the anti-development event; and radical lawmakers were charged with crimes serious enough for them to lose their seats in Legco. From a strategic point of view, it was easy to convict stalwart volunteers or brokers because of their deep involvement in unsanctioned protests; however, the SARG took no action against young activists for fear of public scrutiny and a backlash. Functionally, targeted arrests place a moral burden on protest leaders by punishing their close allies, and deter the formation of hierarchical organizations by destroying the intermediaries. By the time the protest momentum had waned in 2015, 1,003 protestors had been arrested for illegal actions related to the movement; however, as of June 2015, only 5 per cent had been prosecuted, and just 34 per cent of those were found guilty, which is notably lower than the annual average of 49.7 per cent in 2014.Footnote 54 Constrained by a fairly independent judiciary, the regime faced difficulty moving from targeted arrests to mass arrests.

Most importantly, the regime began to use counter-movements as a meso-level reaction. Pro-regime social organizations have a long history but have largely operated underground.Footnote 55 Despite their abundant resources and strong sectorial networks, they are weaker than the pan-democrats in terms of influencing public discourse and attracting popular mobilization, which leaves Hong Kong's activism largely confined to society versus state. After the 2003 rally, communal and kinship organizations such as unions of societies (shetuan 社团) and native associations (tongxianghui 同乡会) were revived, first as agencies of the grassroots machine to contest the pan-democrats and then as sponsors of the counter-movement to contain the social activists. By 2010, pro-regime “civil” organizations had begun to emerge, most notably Caring Hong Kong Power and the Silent Majority for Hong Kong, which claimed to represent the silent majority who treasure order and business, liberty and peace, and to love the city as much as the activists. These pro-regime organizations then aligned to form the “blue-ribbon” movement to counter the “yellow-ribbon” Umbrella Movement. While advocating independence, these citizen-based groups are not shy about preaching their pro-regime agenda and exhibiting their institutional linkages to pro-regime elites or their affiliated societies and associations.Footnote 56 Figure 2 indicates that these groups staged an increasing number of pro-regime protests, each building towards a direct action in a manner similar to that of earlier bottom-up activism. While the state-sponsored protestors have not demobilized protests, they have helped to capitalize on the opposition to activism, trivialize protest claims, and create hefty costs for pro-democracy protestors.

Figure 2: Pro-regime Counter-mobilizations in Hong Kong, 2010–2014

Similar to its counterparts in Russia, Turkey, Syria, Macedonia and Thailand, Hong Kong's hybrid regime has assembled its counter-agencies in the face of protests. What makes Hong Kong unique is that the protests have backfired, even though the regime has become more proactive and coercive. Because protests were reframed social polarizations of supporters and detractors rather than as conflict between the state and civil society, street politics have been increased rather than reduced. Accordingly, when regimes structure repertoires, the relationships between regime openness and protest scale seem to be non-linear. At the peak of the protest cycle, increased regime control and reduced political opportunities failed to demobilize collective action and instead provoked radicalization.

Antecedents of the Umbrella Movement

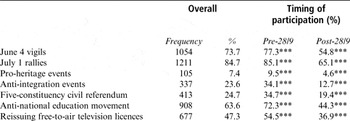

Table 3 documents a positive relationship between participation in street politics and participation in the Umbrella Movement. As many as 85 per cent of protesters had participated in previous sit-ins, rallies or occupations, and only 15 per cent were newcomers with no protest experience. Compared with the vigils and rallies that were staged annually for decades and attracted a popular base, the participation in the one-time anti-national education movement (63.6 per cent) clearly stood out as a rehearsal for the Umbrella Movement. Indeed, young activists, including members of Scholarism and its convenor Joshua Wong 黄之锋, initiated the storming of the Civic Square on 26 September 2014, an event that transformed the scripted “Occupy Central” into a spontaneous occupation. Moreover, although the pro-heritage and anti-integration events were relatively minor, it is clear to see the escalation trend in these small-scale initiatives. The localist framing diffusing these events also appeared to define the protestors: as many as 81 per cent self-identified as pure Hongkongers, much higher than the 42 per cent of the general population and the 60 per cent of 18- to 29-year-olds as of December 2014. Furthermore, the five-constituency civil referendum initiated by the pan-democrats that attracted more than half a million people was a dummy variable showing that despite having much greater participation than any of the critical events did, such electoral politics events barely trigger mobilization.Footnote 57

Table 3: The Protest History of Umbrella Movement Participants

Notes: ***p < 0.001

The firing of tear gas on 28 September 2014 was considered another contingent event that formed “suddenly imposed grievances” that triggered further mobilization. Separating the early mobilizers from the late mobilizers offers insights into the resilience of the movement. Although police violence galvanized late mobilizers, who may not have protested if the regime had not made a mistake, one-third of the protestors were motivated by deep-rooted factors and by the direct actions of the young protesters. While the mere presence of both late mobilizers and early mobilizers did not necessarily sustain the occupation, it did provide political opportunities to check the regime's repression. After all, despite the gradual decline of the protest's strength, the movement was ended by two private court injunctions sought by pro-regime associations and assisted by the police force.

Conclusion

By examining the recurring processes of mass mobilization and regime reactions, I show that the trajectory of Hong Kong's transition is largely shaped by street politics. Although Hong Kong's “civil oligarchy” – similar to any established democracy or autocracy – is most concerned with order, stability and longevity, its hybrid nature limits its tools for fully institutionalizing or repressing dissent. What makes the post-colonial regime special is its multi-level and intertwined configurations comprising the central and local governments and the pro-regime elite, civil liberties, independent judiciary, corporatist domination and a resourceful government, which concurrently provided opportunities for the new activism and neutralized it when contention escalated.

In the early post-colonial era, organized and contained protests served as an acceptable means for both the establishment and the opposition to articulate and aggregate their interests, thereby supporting a nascent but impeded “movement society.” While the 2003 rally triggered systemic regime reconfigurations, it also created a temporal episode of social reconciliation. A series of critical events featuring scale shift, direct actions and symbolic performances spawned a holistic localist framing and the co-optation of stalwart protestors. The regime then manipulated these challenges to foster a milieu of elite cohesion, targeted reprisals and counter-movements. In this regard, institutional weakness or relative deprivation is an inadequate explanation for the diffusion of activism. Instead, the public staging of recurring yet unresolved contentions enhanced the collective recognition that the post-colonial regime was the source of the grievances and stagnation. The defining repertoires of the Umbrella Movement, such as identity politics, decentralized organization and resilient occupation, are clear manifestations of this experience.

In the wider context, Hong Kong's situation addresses certain highly contested notions regarding the sources and impact of political activism. First, although the hybrid regime became proactive and coercive, the protestors refused to obey and instead turned against the regime. Accordingly, while regimes structure repertoires, the relationship between regime openness and mass mobilization is actually intricate and non-linear.Footnote 58 Second, similar to the “occupy” movements in liberal democracies, Hong Kong's new activism enjoys great mobilization capacity but lacks organizational sophistication. This diffuses the vigour of the civil society but seems to prevent the transformation of a spectacular “moment” into a systemic movement.Footnote 59 Third, contrary to the conventional view that political consciousness and collective participation expedite the transition to democracy, what we have witnessed in Hong Kong is a growing polarization between the state and civil society and within civil society. Instead, the paradox of regime instability and longevity seems to endure in hybrid regimes faced with mass protests.

Acknowledgment

An earlier version of this paper was presented at the “Boundaries of democracy” workshop at the University of Hong Kong, 10 October 2014. The author wishes to thank the participants of the workshop for their valuable advice. The author would also like to thank the three anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments. This work was substantially supported by a grant from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (Project No. UGC/FDS16/H04/14).

Biographical note

Edmund Cheng is an assistant professor in comparative politics at Hong Kong Baptist University. He has a PhD in government from the London School of Economics. He researches civil society, contentious politics, political economy and local politics, with a focus on China, Hong Kong and Malaysia, and has published in the International Journal of Heritage Studies, Social Movement Studies and Modern Asian Studies. He is currently working on a project that studies intermediaries in urban China and co-editing a book on Hong Kong's new activism.