No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

Archaeology

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 October 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Other

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1895

References

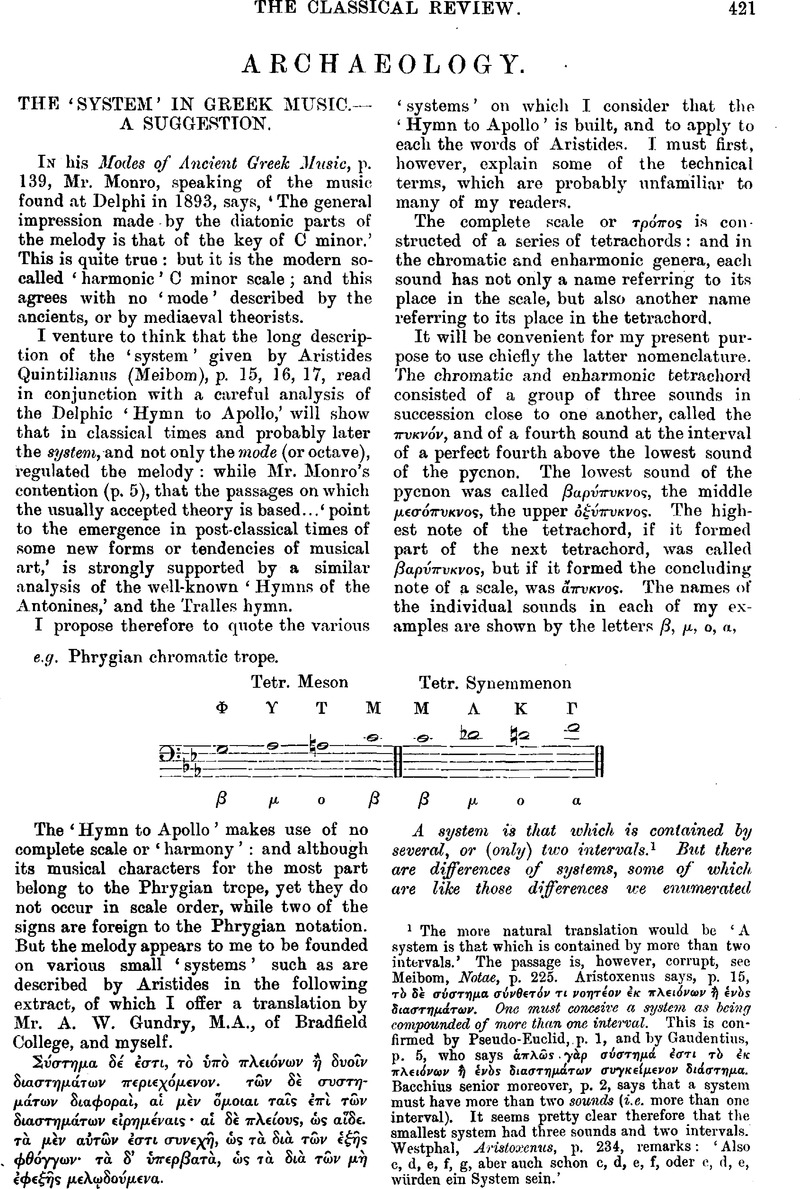

page 421 note 1 The more natural translation would be ‘A system is that which is contained by more than two intervals.’ The passage is, however, corrupt, see Meibom, Notae, p. 225. Aristoxenus says, p. 15, ![]() . One must conceive a system as being compounded of more than one interval. This is confinned by Pseudo-Euclid, p. 1, and by Gaudentius, p. 5, who says

. One must conceive a system as being compounded of more than one interval. This is confinned by Pseudo-Euclid, p. 1, and by Gaudentius, p. 5, who says ![]() Bacchius senior moreover, p. 2, says that a system must have more than two sounds (i.e. more than one interval). It seems pretty clear therefore that the smallest system had three sounds and two intervals. Westphal, Aristoxenus, p. 234, remarks: ‘Also c, d, e, f, g, aber auch schon c, d, e, f, oder c, d, e, würden em System sein.’

Bacchius senior moreover, p. 2, says that a system must have more than two sounds (i.e. more than one interval). It seems pretty clear therefore that the smallest system had three sounds and two intervals. Westphal, Aristoxenus, p. 234, remarks: ‘Also c, d, e, f, g, aber auch schon c, d, e, f, oder c, d, e, würden em System sein.’

page 422 note 1 See Aristides, p. 13, Pseudo-Euclid, p. 12, gives four differences of system as common with those of intervals, viz. difference of magnitude, of genus, of consonance and dissonance, of rational and irrational. Aristoxenus, p. 74, speaks of ‘species’ and ‘scheme’ as two names referring to the same thing, viz. the arrangement of the intervals in a system. Unforintervals, tunately his description of the systems is lost.

page 422 note 2 ![]() , Pseudp-Euclid, p. 9.

, Pseudp-Euclid, p. 9.

page 423 note 1 A change from one system to another is called ‘metabole’ of system, and the frequent allusions to it show that it must have played an important part in composition.

page 424 note 1 Pseudo-Euclid in the parallel passage, p. 17, uses the word ![]() , which makes the sentence far more intelligible.

, which makes the sentence far more intelligible.

page 424 note 2 See Ptolemy, Harmonics, Boolk ii. eh. 4.

page 424 note 3 It is evident from the context that only trite nete diezeugmenon are referred to. In the Phrygian chromatic trope these notes would be respectively

page 425 note 1 I.e. the sounds of the upper octave severally coincide with those of the lower octave.

page 425 note 2 The Pythagoreans and Aristoxenians were the ancient representatives of two opposing sects of musicians, which continued all through the middle ages, exist now, and always will exist. The question between them is not in reality what is the truth in musical matters, but what is most congenial to the individual temperament and brain-power of each musician. Music has its mathematical and its emotional side: and each individual will incline to the Pythagorean, the scientific side, or the Aristoxenian, the artistic, emotional, empirical side, according to his temperament. The scientific and empirical elements find their natural meeting-ground in instruments of fixed pitch, such as the organ and piano, in the tuning of which a compromise has to be effected between mathematical precision and empiricism. Our Universities now demand of candidates for Musical Degrees a knowledge of the chief features of both these opposing sides of music; but the double knowledge is not naturally cultivated by the same individual.

page 426 note 1 E.g. to the octave F to F (white keys of the piano) add the five flats proper to the Dorian key (B flat minor) and the Dorian octave is produced.

page 427 note 1 See Day's Music of Southern India.

page 428 note 1 Athenaeum, 12 Oct.

page 428 note 2 Notizie dei Lincei, Jan.-Mar. 1895.

page 428 note 3 Academy, 5 Oct.