No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

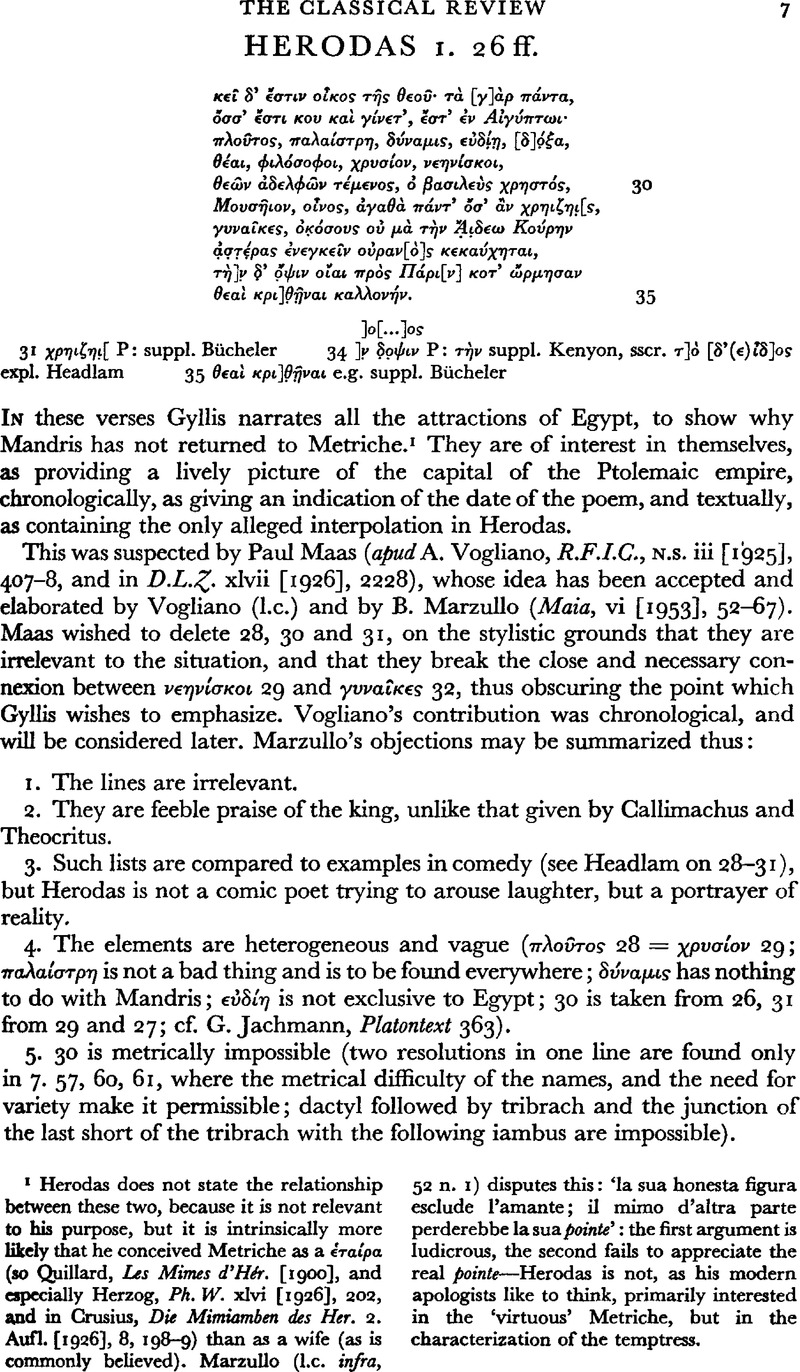

Herodas 1. 26 ff

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1965

References

page 7 note 1 Herodas does not state the relationship between these two, because it is not relevant to his purpose, but it is intrinsically more likely that he conceived Metriche as a ἑταίρα (so Quillard, , Les Mimes d'Hér. [1900]Google Scholar, and especially Herzog, , Ph. W. xlvi [1926], 202Google Scholar, and in Crusius, , Die Mimiamben des Her. 2. Aufl. [1926], 8, 198–199)Google Scholar than as a wife (as is commonly believed). Marzullo (l.c. infra, 52 n. 1) disputes this: ‘la sua honesta figura esclude l'amante; il mimo d'altra parte perderebbe la sua pointe’: the first argument is ludicrous, the second fails to appreciate the real pointe—Herodas is not, as his modern apologists like to think, primarily interested in the ‘virtuous’ Metriche, but in the characterization of the temptress.

page 8 note 1 The view that Herodas was a ‘realist’, for long universal and still surviving sporadically, cannot be fully dealt with here. The essential point is that no one who aspired to a genuine realism could use a dialect and metre as archaic, recondite and artificial as those of Herodas. The apparently realistic subject-matter should not blind us to this.

page 8 note 2 White, J. W., Verse of Gr. Com., 49, 62.Google Scholar

page 8 note 3 Weil, , J. des Sav. 1891, 657Google Scholar. Herodas deliberately ignores logical sequence on a larger scale in Battaros' oration in 2.

page 8 note 4 Meister, followed inter alios by Headlam and (essentially) by Groeneboom, understood it of the παῖδες βασίειοι, the cadets and pages of the Ptolemies. If it is erotic, it would be the only reference to paederasty in Herodas.

page 8 note 5 More exactly to c. 280—c. 265, as I hope to show elsewhere.

page 9 note 1 Cataudella's idea that χρηστός refers to the title Εὐεργέτης would be possible if the dating were otherwise proved, but the epithet is too general to be used as a proof itself.

page 9 note 2 Herzog's detailed discussion of the relationship of Ptolemy Soter and Berenice and their place in the state cult need not be gone into here. Cf. Maas, , D.L.Z. xlvii (1926), 2228Google Scholar; Vogliano, , R.F.I.C. N.S. v (1927), 77–78Google Scholar; Volkmann, , R.-E. xxiii. 2, 1638 (with further literature).Google Scholar

page 9 note 3 Wilamowitz, , Gl.d.Hell. ii. 262 ff.(2.Aufl. 259 ff.).Google Scholar

page 9 note 4 Nilsson, , Gesch. d. gr. Rel. ii. 128 ff.Google Scholar