No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

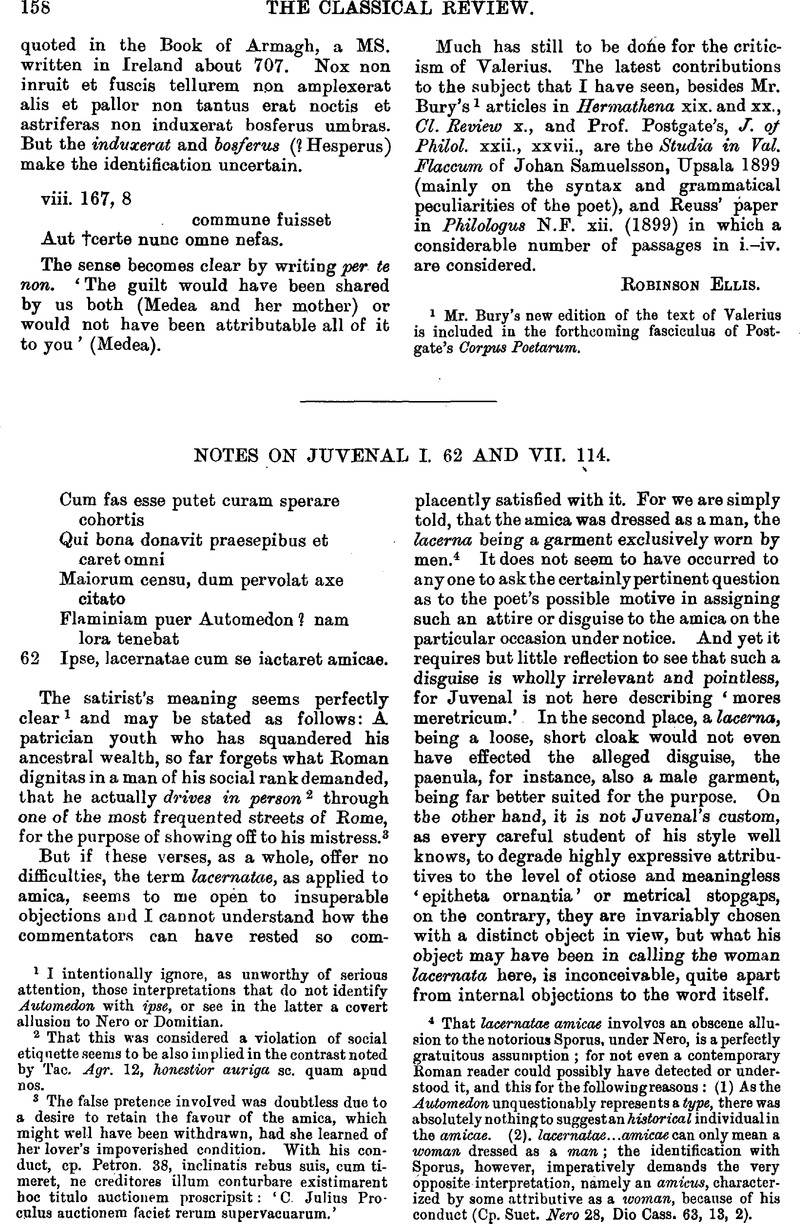

Notes on Juvenal I. 62 and VII. 114

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 October 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Original Contributions

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1900

References

page 158 note 1 I intentionally ignore, as unworthy of serious attention, those interpretations that do not identify Automedon with ipse, or see in the latter a covert allusion to Nero or Domitian.

page 158 note 2 That this was considered a violation of social etiqnette seems to be also implied in the contrast noted by Tac. Agr. 12, honestior auriga sc. quam apud nos.

page 158 note 3 The false pretence involved was doubtless due to a desire to retain the favour of the amica, which might well have been withdrawn, had she learned of her lover's impoverished condition. With his conduct, cp. Petron. 38, inclinatis rebus suis, cum timeret, ne creditores ilium conturbare existimarent hoc titulo auctionem proscripsit: ‘C Julius Proculus auctionem faciet rerum supervacuarum.’

page 158 note 4 That lacernatae amicae involves an obscene allusion to the notorious Sporus, under Nero, is a perfectly gratuitous assumption ; for not even a contemporary Roman reader could possibly have detected or understood it, and this for the following reasons : (1) As the Automedon unquestionably represents a type, there was absolutely nothing to suggest an historical in dividual in the amicae. (2). lacernatae…amicae can only mean a woman dressed as a man; the identification with Sporus, however, imperatively demands the very opposite interpretation, namely an amicus, characterized by some attributive as a woman, because of his conduct (Cp. Suet. Nero 28, Dio Cass. 63, 13, 2).

page 159 note 1 Cp. Mart. x. 6, 6, Totaque Flaminia Roma videnda via; Tac. Hist. ii. 64, Flaminiae viae celebritate.

page 159 note 2 I know of only two analogous instances in Juvenal, viz. iii. 25, vi. 456.

page 159 note 3 One may compare the characteristic mantle of the German ‘Droschkenkutscher,’ worn in cold and rainy weather, although a garment of similar cut, but of finer texture, is also used by the well-to-do. So likewise we occasionally hear of costly lacernae, e.g. Mart. v. 8, 5. I note that Friedländer without comment translates lacernatus in the Petronian passage by ‘Kutschermantel.’

page 160 note 1 Henzen, cited by Friedländer, Sittengesch. ii. 328, 2. The original article is not accessible to me.

page 160 note 2 Cp. the πρ⋯τος ⋯ν⋯κα in the Didascalia. Greek terms of the race track were in all probability as much in vogue in Rome as the similar English terms were adopted on the continent of Europe. So the words expressive of approval were also often Greek, e.g. ςοφ⋯ς, π⋯λιν, euge.