No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

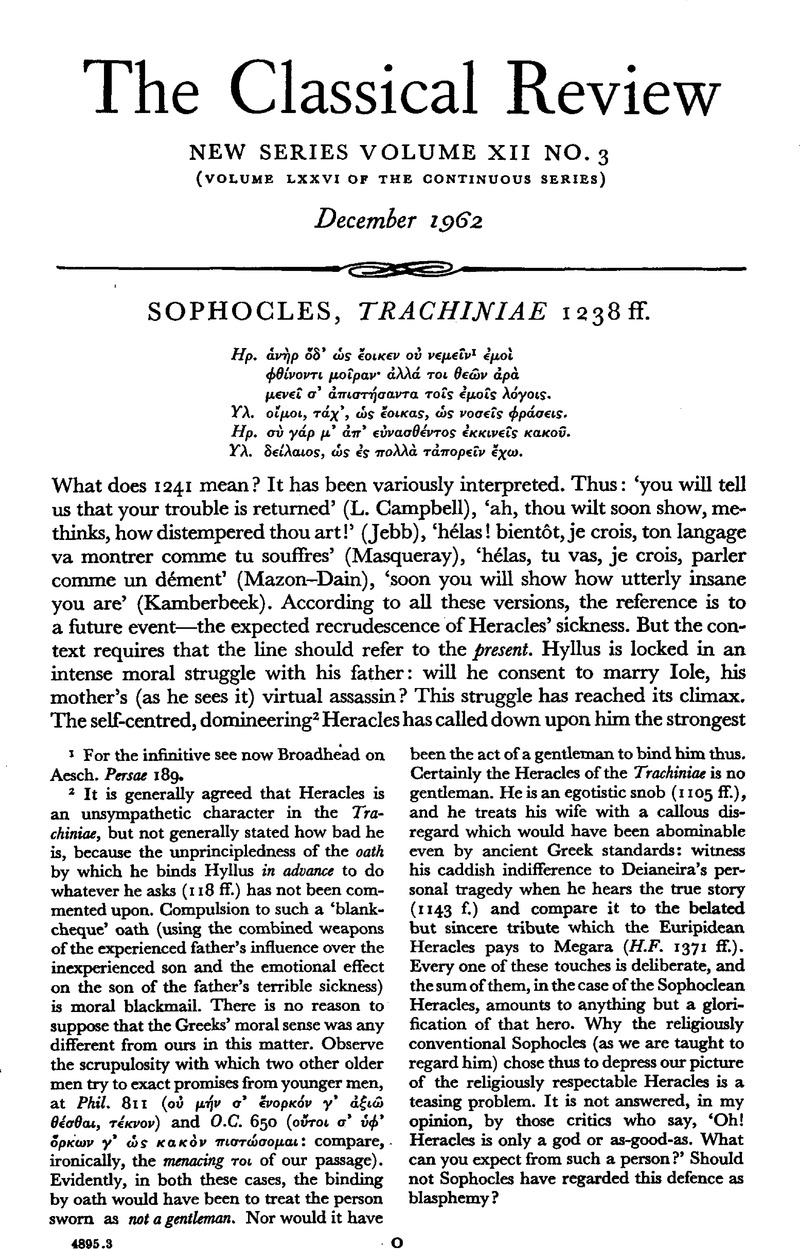

Sophocles, Trachiniae 1238 ff

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The Classical Association 1962

References

1 For the infinitive see now Broadhead on Aesch. Persae 189.

2 It is generally agreed that Heracles is an unsympathetic character in the Trachiniae, but not generally stated how bad he is, because the unprincipledness of the oath by which he binds Hyllus in advance to do whatever he asks (118 ff.) has not been commented upon. Compulsion to such a ‘blank-cheque’ oath (using the combined weapons of the experienced father's influence over the inexperienced son and the emotional effect on the son of the father's terrible sickness) is moral blackmail. There is no reason to suppose that the Greeks' moral sense was any different from ours in this matter. Observe the scrupulosity with which two other older men try to exact promises from younger men, at Phil. 811 (οὐ μ⋯ν σ' ἔνορκ⋯ν γ' ⋯ξι⋯θ⋯σθαι, τ⋯κνον) and O.C. 650 (οὔτοι σ' ὑφ' ⋯ρκων γ' ὡς κακ⋯ν πιστώσομαι: compare, ironically, the menacing τοι of our passage). Evidently, in both these cases, the binding by oath would have been to treat the person sworn as not a gentleman. Nor would it have been the act of a gentleman to bind him thus. Certainly the Heracles of the Trachiniae is no gentleman. He is an egotistic snob (1105 ff.), and he treats his wife with a callous disregard which would have been abominable even by ancient Greek standards: witness his caddish indifference to Deianeira's personal tragedy when he hears the true story (1143 f.) and compare it to the belated but sincere tribute which the Euripidean Heracles pays to Megara (H.F. 1371 ff.). Every one of these touches is deliberate, and the sum of them, in the case of the Sophoclean Heracles, amounts to anything but a glorification of that hero. Why the religiously conventional Sophocles (as we are taught to regard him) chose thus to depress our picture of the religiously respectable Heracles is a teasing problem. It is not answered, in my opinion, by those critics who say, ‘Oh! Heracles is only a god or as-good-as. What can you expect from such a person?’ Should not Sophocles have regarded this defence as blasphemy?