No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

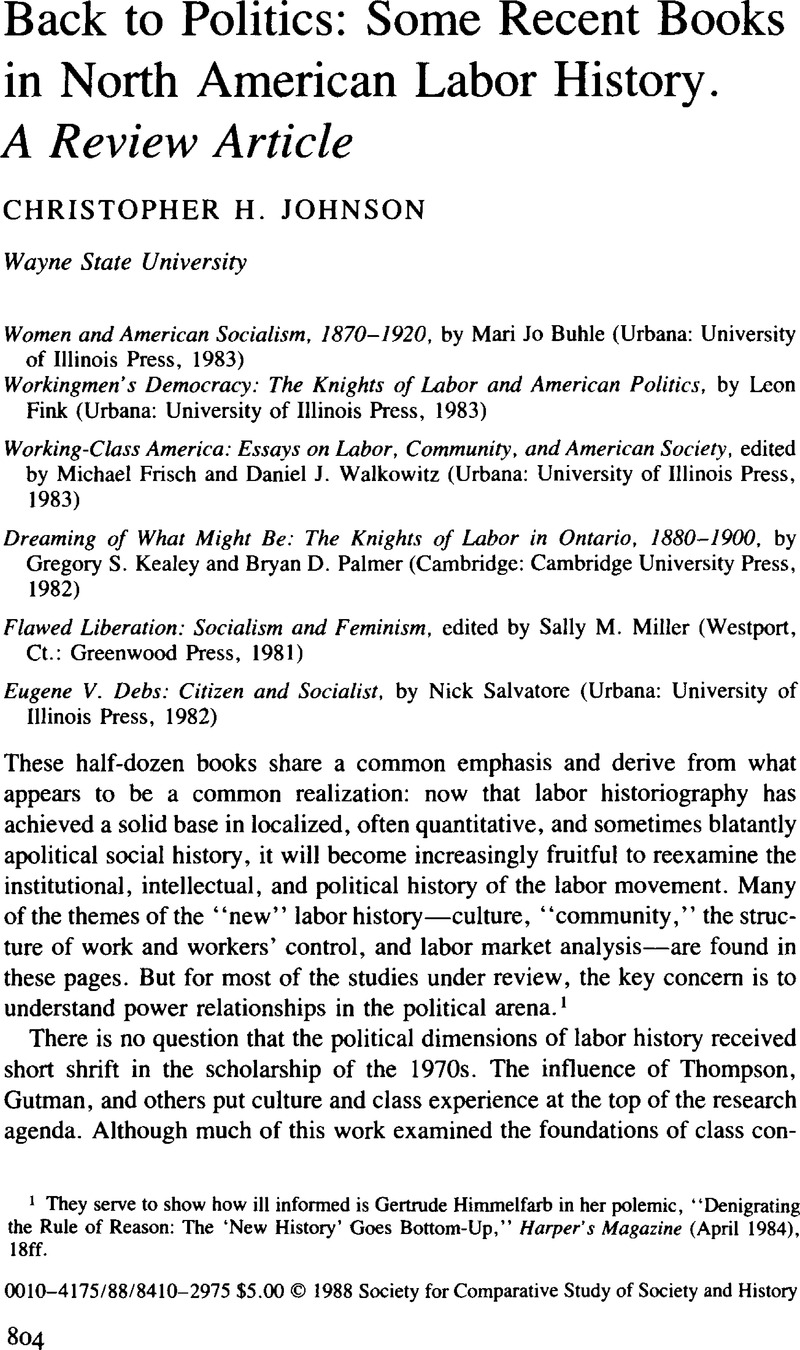

Back to Politics: Some Recent Books in North American Labor History. A Review Article

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 03 June 2009

Abstract

- Type

- CSSH Discussion

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Society for the Comparative Study of Society and History 1988

References

1 They serve to show how ill informed is Gertrude Himmelfarb in her polemic, “Denigrating the Rule of Reason: The ‘New History’ Goes Bottom-Up,” Harper's Magazine (04 1984), 18ff.Google Scholar

2 Stearns, Peter, Lives of Labor (New York: Holmes and Meier, 1974);Google ScholarMeacham, Standish, A Life Apart: The British Working Class, 1890–1914 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1977);Google Scholar and Jones, Gareth Stedman, “Working-Class Culture and Working-Class Politics in London, 1870–1890,” Journal of Social History, 7: spring (1974), 460–508.CrossRefGoogle Scholar But see also his Introduction in Languages of Class (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983).Google Scholar

3 See especially, Cronin, James E., “Labor Insurgency and Class Formation: Comparative Perspectives on the Crisis of 1917–1920 in Europe,”Google Scholar in Cronin, James E. and Sirianni, Carmen, eds., Work, Community, and Power: The Experience of Labor in Europe and America, 1900–1925 (Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1983),Google Scholar but the entire book forms a coherent refutation of these arguments. For a perceptive critique of American ethno-labor “community” history see Bukowczyk, John J., “Immigrants and their Communities: A Review Essay,” International Labor and Working Class History, 25: spring (1984), 30–35.Google Scholar

4 Racière, Jacques, “De Pelloutier è Hitler: syndicalisme et collaboration,” Les révoltes logiques, 4 (Winter 1977), 23–61,Google Scholar and “The Myth of the Artisan: Critical Reflections on a Category in Social History,” International Labor and Working Class History, 24 (Fall 1983), 116,Google Scholar with “Responses” by William H. Sewell, Jr., and Christopher H. Johnson, 17–25. See also McDonnell, Lawrence, “‘You are too sentimental’: Problems and Suggestions for a New Labor History,” Journal of Social History, 17: Summer (1983–1984), 629–54.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

5 The nastiest of this genre was by Judt, Tony, “The Clown in Regal Purple,” History Workshop (Spring 1979), 65–94.Google Scholar

6 Wilenz, Sean, “Artisan Republican Festivals and the Rise of Class Conflict in New York City, 1788–1837,” 37–77;Google ScholarCouvares, Francis, “The Triumph of Commerce: Class Culture and Mass Culture in Pittsburgh,” 123–52;Google ScholarFreeman, Joshua, “Catholics, Communists, and Republicans: Irish Workers and the Organization of the Transport Workers Union,” 256–83, in Frisch and Walkowitz.Google Scholar

7 The journal LabourLe Travailleur is the best place to start for those interested in the flowering of Canadian labor history. For a review of a recent colloque in Paris on American exceptionalism and the doubts raised about the validity of the concept see Montgomery, David, “Why is There no Socialism in America? Conference in Paris,” International Labor and Working Class History, 24 (Fall 1983), 67–68.Google Scholar

8 See Gordon, David, Reich, Michael, and Edwards, Richard C., Segmented Work, Divided Workers: The Historical Transformation of Labor in the United States (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1982).Google Scholar Curiously, they put little stress on this period of resistance. Edwards, But, in Contested Terrain (New York: Basic Books, 1979), provides a much clearer framework, which he calls “organizational uncoupling,” or the inherent contradictions of the “drive system” and hierarchical control coming home to roost.Google Scholar

9 Maier, Charles, Recasting Bourgeois Europe (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1975).Google Scholar

10 England is an exception, despite Mosley and Co., but the Labour Party and the T.U.C. formed a labor bloc (however moderate) that had no equivalent in the United States. On the radical right in America, see the fine comparative analysis by Amano, Peter in this journal: “Vigilante Fascism: The Black Legion as an American Hybrid,” CSSH, 25:3 (1983), 490–524.Google Scholar

11 See the cogent analyses of Foner, Eric, “Why is there no Socialism in the United States,” History Workshop Journal (Spring 1984), 57–80;Google Scholar and Wilenz, Sean, “Against Exceptionalism: Class Consciousness and the American Labor Movement,” International Labor and Working Class History (Fall 1984), 1–24;Google Scholar but in support of the perspective offered here see Michael Hanagan, “Response to Wilenz,” ibid., 31–36.

12 See, especially, the recent discussion of working-class politics in France by Berlanstein, Lenard, The Working People of Paris, 1871–1914 (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins, 1984), ch. 6.Google Scholar

13 Jones, Gareth Stedman, “Rethinking Chartism,” in Languages of Class (90–178), argues that Chartism's promises of social reform through the acquisition of the vote led to its collapse when Peelite Toryism carried out reforms in the 1840s without granting the vote.Google Scholar

14 Boxer, Marilyn J. and Quataert, Jean H., eds., Socialist Women: European Socialist Feminism in the Nineteenth and Early Twentieth Centuries (New York: Elsevier, 1978);Google ScholarQuataert, , Reluctant Feminists: Socialist Women in Imperial Germany, 1885–1917 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1979);Google ScholarEvans, Richard J., The Feminist Movement in Germany, 1894–1933 (London: Thames and Hudson, 1976)Google Scholar and “German Social Democracy and Women's Suffrage, 1891–1918,” Journal of Contemporary History, 15:4 (1980), 533–57.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

15 Thomas, Edith, Pauline Roland: Socialisms et féminisme au XIXe siècle (Paris, 1956), 108–57;Google ScholarRanvier, Adrien, “Une féministe de 1848, Jeanne Deroin,” La Révolution de 1848, IV (1907–1908), 317–55, 421–30, 480–98;Google ScholarMoses, Claire, French Feminism in the Nineteenth Century (Albany: State University of New York Press, 1984).Google Scholar

16 Barbara Engels' recent book on the women in the Russian populist and socialist movements shows the limited interest in “women's issues” or indeed, personal life, manifested by these revolutionaries.

17 See Buhle's moving mini-biography of Morrow Lewis in Miller, 61–86.

18 Pratt, William C. in his careful study of a local S.P. at a later time found the same phenomenon. “Women Socialists and their Male Comrades: The Reading Experience, 1927–1936,” in Miller, 145–78.Google Scholar

19 Although these comments are drawn from Gretchen and Kent Kreuters' research on Simons (Miller, 37–60), I am not convinced by their argument that she both “abondoned her feminism” and made her shift to the right because she was overwhelmed by family responsibilities. She did, after all, go on, after leaving the Socialist Party, to (1) become the Illinois president of the League, and (2) to obtain a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Chicago (they do not indicate the subject matter). Although socialism was “eclipsed,” a “political and professional life” was not. What the Kreuters are trying to prove is that family life, the “private sphere” was inimical to Simons' full development. This may be to an extent true (especially with Algie as a husband), but her path seems to be fairly typical of many middle-class, politically involved women (and men) of the age: a move from moderate socialism to progressivism. The Kreuters follow a line, in fact, that has plenty of current ideological support; for the controversy in European family and working-class history, see Hilden, Patricia, “Family History vs. Women in History: a Critique of Tilly and Scott,”Google Scholar and Scott, Joan Wallach, “Reply to the Hilden Critique,” International Labor and Working Class History, 16 (Fall 1979), 1–17.Google Scholar

20 The Knights of Labor—as Palmer and Kealey show so well for Ontario—exhibited the same Victorian spirit of gallantry, yet at the same time “raised the woman question within the Ontario labor movement for the first time” (p. 317). They fought valiantly for women strikers and took a firm stand in favor of female suffrage. But like the American socialists, they treated the breaking of sexual taboos as another matter, as exemplified in the case of the pressured withdrawal from a local assembly by a white woman married to a black man. (Blacks, of course, were welcomed as members of the Knights.)Google Scholar

21 Alexander, Sally, “Women's Work in Nineteenth-Century London: A Study of the Years 1820–1850,” in The Rights and Wrongs of Women, Mitchell, J. and Oakley, A., eds. (London, 1976);Google ScholarJohnson, Christopher H., “Economic Change and Artisan Discontent: The Tailors' History, 1800–1850,” in Price, Roger, ed., Revolution and Reaction, (London: Thames and Hudson, 1975). Stansell in fact gives little emphasis to the ready-made revolution itself, which was the essential economic dynamic behind the entire process.Google Scholar

22 On this process among bourgeois women in France, see Smith, Bonnie, Ladies of the Leisure Class: The Bourgouises of Northern France in the Nineteenth Century (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1981).Google Scholar

23 See Davis, Natalie, “Women on Top,” in her Culture and Society in Early Modern France (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1977).Google Scholar A variety of nineteenth-century studies confirm what Zola depicted (however negatively) in Germinal. For the frightened images of Zola and other bourgeois writers, see Barrows, Susanna, Distorting Mirrors: Visions of the Crowd in Late Nineteenth-Century France (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981).Google Scholar

24 Bernard, Elaine, “Workers Control at B.C. Telephone: The Shape of Things to Come,” Simon Fraser University, manuscript, 1984.Google Scholar

25 This does not mean, however, that movement from job to job and from agriculture to industry and back was impossible for European workers. See Johnson, Christopher H., “Patterns of Proletarianization: Parisian Tailors and Lodève Woolens Workers,” in Consciousness and Class Experience in Nineteenth-Century Europe, Merriman, John, ed. (New York: Holmes and Meier, 1980);Google ScholarFoster, John, Class Struggle and the Industrial Revolution (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1974);CrossRefGoogle ScholarReddy, William, The Making of Market Culture (on the northern French textile industry) (New York: Cambridge University Press, 1984);Google Scholar and, still fundamental, Braun, Rudolph, Industrialisierung und Volksleben, 2 vols. (Zurich, 1961).Google Scholar Large advances followed by a form of industrial peonage and an official employment notebook called the livret were widely used to pin workers down in France, the one country in industrial Europe where agricultural change and population pressure did not produce flocks of factory job-seekers. On the differences between the French and other European labor markets in the nineteenth century, see the superb essay by Cottereau, Alain, “The Distinctiveness of Working-Class Cultures in France, 1848–1900,” in Working-Class Formation, Katznelson, Ira and Zolberg, Aristide, eds. (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986), 111–54.Google Scholar

26 See Thompson, E. P., The Making of the English Working Class (London: Gollanz, 1963), 350–400;Google ScholarBerenson, Edward, Populist Religion and Left-Wing Politics in France, 1830–1852 (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1984).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

27 On the evolution of Lenin's program, see Sirianni, Carmen, Workers' Control and Socialist Democracy (New York: Schocken, 1982).Google Scholar

28 As Lichtenstein puts it: “Of greater long-range interest was an oppositional infrastructure and a pre-existing tradition of struggle into which [the] new workers could be acculturated. Thus, the center of working-class militancy during World War II was not in the ‘cornfield factories’ erected far from the older centers of UAW strength, but rather in the unionized shops of Detroit and other industrial centers.” On the wildcats, see especially Glaberman, Martin, Wartime Strikes: The Struggle against the No-Strike Pledge in the UAW during World War II (Detroit: Bewick Editions, 1980).Google Scholar

29 Wigderson, Seth, “The UAW in the 1950s” (paper presented at the Social Science History Association meeting, Washington, D.C., 29 10 1984).Google Scholar No one has yet put the whole question of this transition in a perspective that rises much above polemic. The best attempt is probably Cochran, Bert, Labor and Communism: The Conflict that Shaped American Unions (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1977).Google Scholar For management's outlook and actions, we have the excellent book by Hams, Howell, The Right to Manage: Industrial Relations Policies of American Business in the 1940s (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1982).Google Scholar