Introduction

…never more than at a time of extreme social crisis does the atmosphere become a determining factor in the way people respond to events.

——Ronald FraserFootnote 2In 1964, Louis Hartz claimed that the use of violence by powerful white elites against and on behalf of the state has been a central feature of the histories of both South Africa and the United States. Once the two societies were founded as white settler states, no century passed without some flashpoint becoming the defining event of the era. Each of these events gave expression to the aspirations and grievances of white elites, while suppressing those of the subaltern races and popular classes under the rubric of patriotism or home rule.Footnote 3 Territorial expansion, the institutionalization of white supremacy, and the creation of coercive labor systems all moved forward during periods when elite whites could exercise their capacity for collective and personal violence with few constraints.Footnote 4

As segregation replaced less subtle forms of white supremacy, violence or the threat of violence achieved a more prominent place in the ongoing public conversations that elite whites conducted with the state and the disenfranchised. Yet only a handful of comparative historians of segregation in the United States and South Africa have provided a detailed examination of what Kenneth Burke and C. Wright Mills might have called the “grammar of motives” behind the violence of white elites.Footnote 5 We have seen little work on this subject that examines it as poignantly as, say, C.L.R. James did for slave rebels-turned-revolutionaries in the Black Jacobins, Charles Tilly for rural Roman Catholic opponents of the French Revolution in The Vendée, or Roy Hofheinz Jr. for restive Chinese peasants-turned-antimony miners in Hunan Province during the failed Autumn Harvest Rising in The Broken Wave. Footnote 6 Short of the American Civil War and the 1899–1902 Anglo-Boer or South African War, historians have elided the timing, frequency, justification, and meaning of many major flashpoints in these two societies.Footnote 7

Map 1. Map of Louisiana in 1850. Historic New Orleans Collection, 00-21.

It is not surprising that vigilantism and terror should command greater attention from scholars given the violent nature of our own times. Among historians of the American South and South Africa, the late George Frederickson’s views on extra-legal or unofficial white violence continue to be widely accepted. Frederickson put forth his views during what many consider the heyday of comparative American and South African historiography in the early 1980s in a synthetic work entitled White Supremacy. John Cell’s Segregation: The Highest Stage of White Supremacy, the most detailed comparative study of segregation of South Africa and the American South, soon complemented Frederickson’s monograph. Cell contended that segregation provided an “alternative” to “the uncontrolled violence of anarchy.”Footnote 8

Frederickson, on the other hand, argues that unofficial violence, bolstered by white authority and the disenfranchisement of blacks in the American South, established “a rigid caste division between racial groups that were inextricably bound to the same culture, society, economy and legal system.” However, he maintains that in South Africa unofficial violence does “not figure prominently.”Footnote 9 Under the unwanted protection of the British imperial condominium government until 1899, the Boer republics of the Transvaal and Orange Free State and the English-speaking colonies of the Cape and Natal bolstered “white supremacy” using the police and the military. This arrangement also sought to confine various groups of Africans to a series of “native reserves.” According to Fredrickson, this system of “native segregation” enforced “a post conquest pattern of vertical ethnic pluralism,” and attempted to keep the white minority in control while pushing more Africans into the reserves, from which they could be easily drawn as cheap labor.Footnote 10

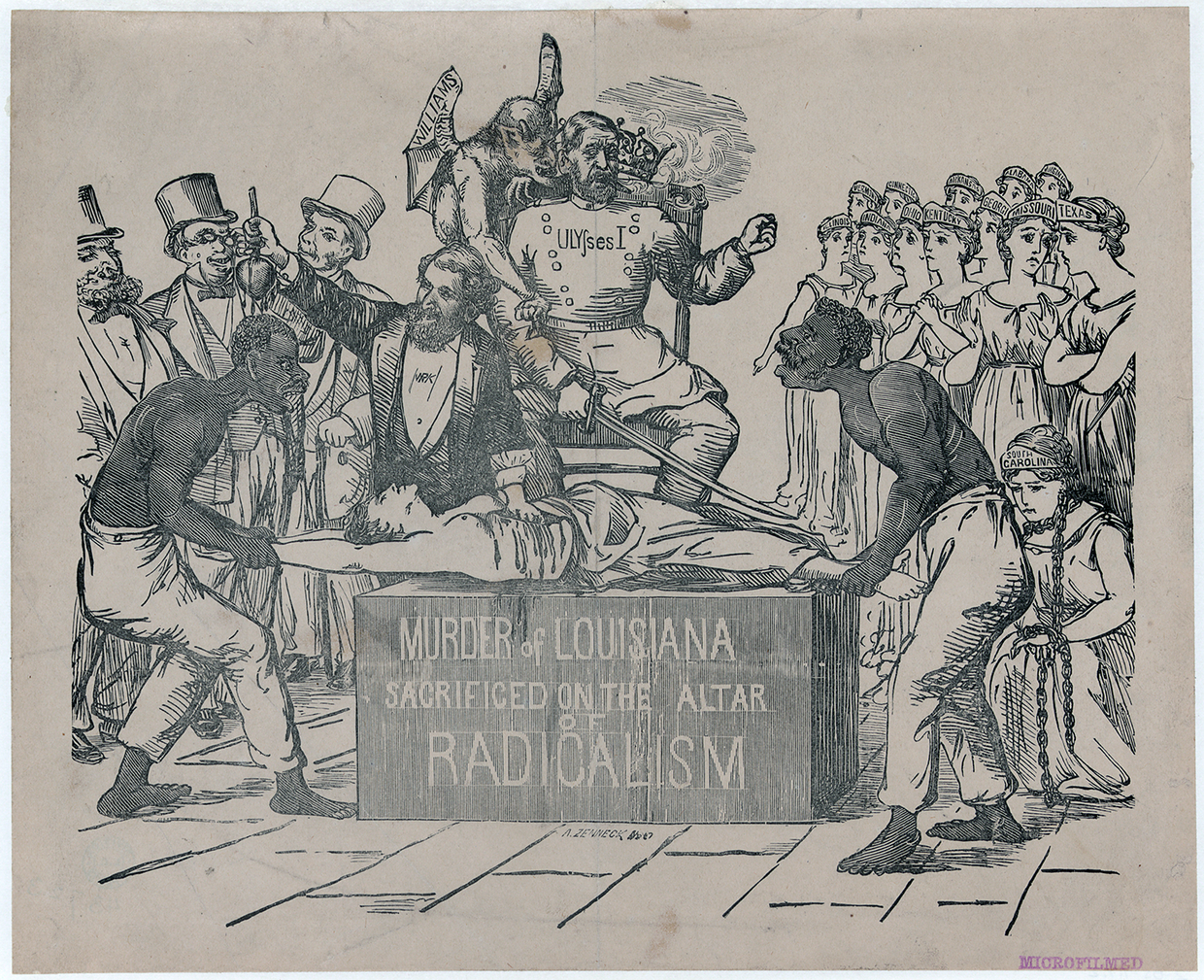

Image 1. White League propaganda cartoon, “Murder of Louisiana Sacrificed on the Alter of Radicalism,” 1871. Library of Congress item 2008661710.

Frederickson’s dismissal of the influence of unofficial violence in the history of segregation in South Africa requires closer scrutiny. The years following the Civil War and the South African War laid the foundation for a dramatic transformation of agriculture and industry in both societies. The stakes were different but equally high for the British Empire and the Federal Government of the United States. Meanwhile, Boer landlords and former American slaveholders selectively embraced the benefits that nineteenth-century economic liberalism proclaimed. During the respective postwar or “Reconstruction” periods, each country experienced a rapid but selective form of industrialization that, in turn, evoked an unprecedented set of responses from people who made their living from the land.Footnote 11

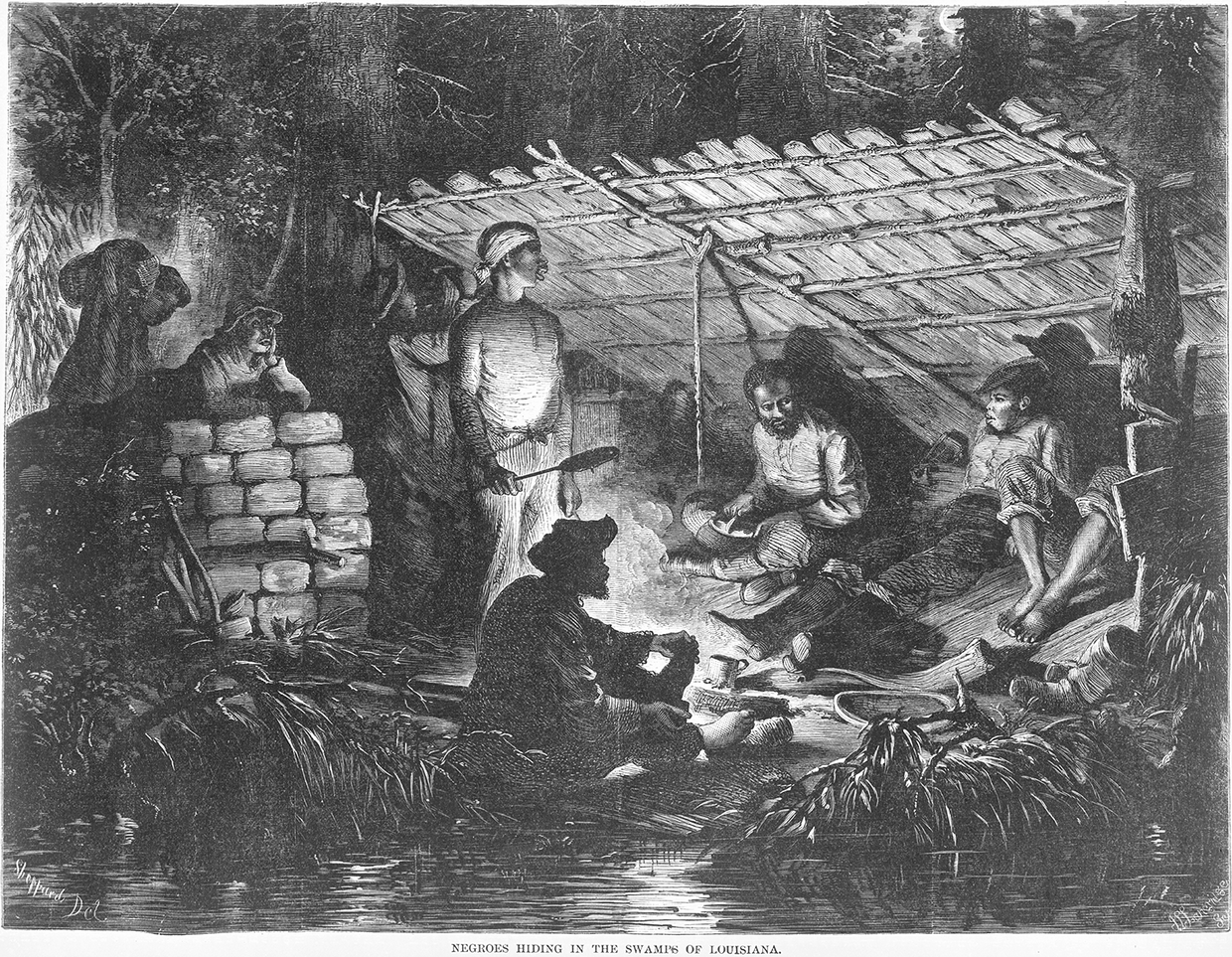

Image 2. “Negroes Hiding in the Swamps of Louisiana.” James Langridge, engraver; William Ludwell Sheppard, artist. Published in Harper’s Weekly, 10 May 1873. Library of Congress item 94507781.

What made these two white agrarian elites act in such a consistently violent manner over many generations? Were there repeated clashes of expectations and outcomes that had their origins deep in past traditions? Is there a larger field of concerns that we must construct first before we can see why the aggrieved parties chose to act so violently?

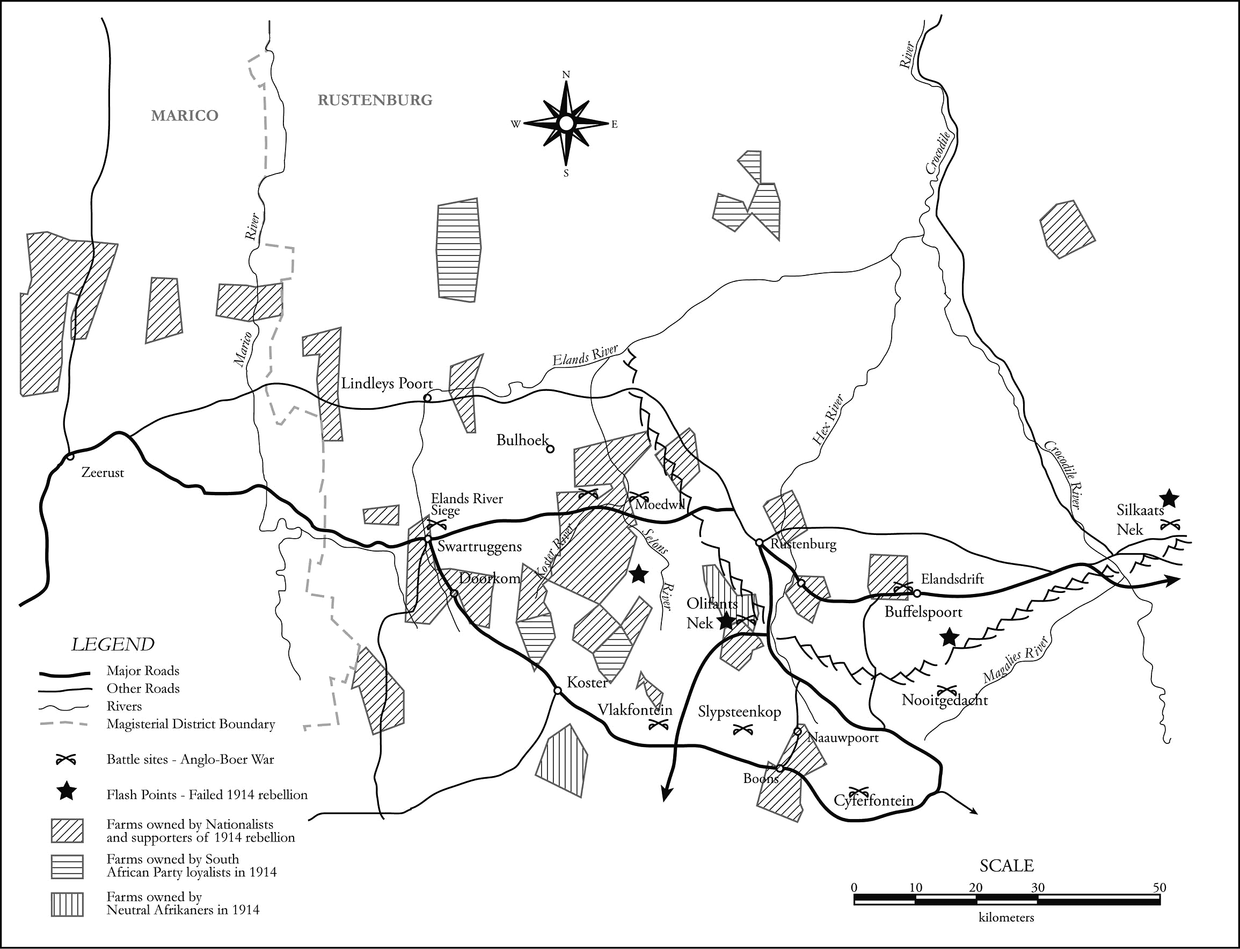

Map 2. The Rustenburg and Marico districts of South Africa. Map by Don Sluter, 2015.

Violence and aggression in any society embrace related problems of social and political costs, morality, social cohesion and authority—in short, who, with the consent of the state, can do violence to other people. Because there is no known human society where violence and aggression do not occur and because the range of aggression can also vary—from a hostile glance to the extermination of entire segments of the population—it is more useful to think of violence in terms of capacities rather than instincts. Actual acts of terror and violence only amount to the most obvious aspect of the problem. One must reconstruct why an act of violence occurred by putting its details into a relationship that is consistent with the aims of the perpetrators and the amount of force that a given state would impose upon them before, during, and after the act was completed. Acts of collective violence are rarely gratuitous.Footnote 12

I draw on actual acts of violence and their immediate aftermath during the Reconstruction era in Louisiana for the American examples here. The range of violent responses from ex-slaveholders to Louisiana’s new post-1868 state constitution and the loss of absolute control over black labor took many forms. But the most immediate objective of terrorist groups such as the White League was to broaden their constituency by incorporating a range of new grievances against the Federal and state governments. Arming Louisiana’s rural white population and promulgating the “ideology of the deed” were central to their objectives after 1868.Footnote 13 A cascade of rumors about an imminent black insurrection and the falling price of cotton drove the creation of a broader white constituency for terrorist activity.

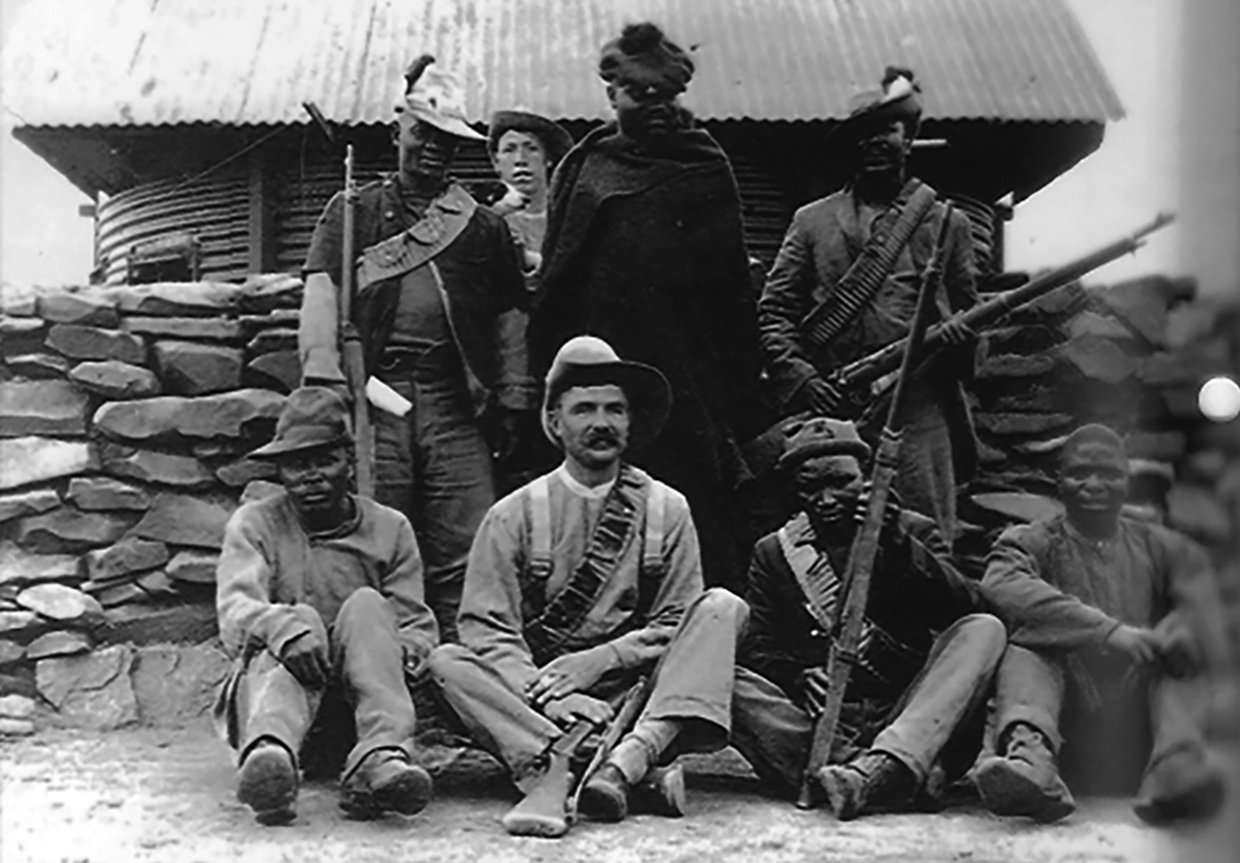

Image 3 “African irregulars fighting for the British.” National Archives of South Africa.

My South African examples focus exclusively on the aftermath of specific moments of collective violence that took place during the post-July 1900 guerrilla phase of the Anglo-Boer or South African War. After December 1900, there arose what one might call a “war within the war.” This war within the war amounted to men, especially young men, carrying out atrocious instances of violence in local skirmishes without the direct knowledge of the Boer Republican Army’s mobile general staff. Occasionally the general staff or a given fighting commandant would weigh in to interpret and claim the tactical advantages of these more parochial struggles.Footnote 14 Rumors of former African irregulars squirreling away arms caches also drove moral panics among the countryside’s white population. Milner’s postwar Reconstruction administration did not dispel these rumors, nor did it reduce intermittent outbreaks of violence and threats of violence.Footnote 15

The Post-Civil War South

At the close of the American Civil War the South’s slaveholders found themselves on the losing end of one of the bloodiest conflicts of the industrial epoch. Their responses tell us much about the shortsightedness of their conquerors, as well as how the defeated agrarian elite sought to position itself in a world that industrial capitalism and mechanized warfare was recasting.Footnote 16

Faced with indecisive and sporadic opposition from the national government at the close of the war, a notable segment of ex-slaveholders determined to prevent any further encroachment on what they believed to be their legacy. Many initiated protracted but sustained campaigns of terror. Their success was due in part to the centrality of the South’s cotton to the national economy of the United States.Footnote 17 Consequently behind the most horrifying and atrocious displays of violence lay the desire of ex-slaveholders to control the disposal of the cotton harvest as well as the labor of the freed people.Footnote 18

The chain of violence in Caddo and the other Red River Parishes of Louisiana compel one to reexamine conclusions about conflicts between blacks and whites in the rural South.Footnote 19 Many defied characterization and underscored the tragic dimensions of the South’s plight.Footnote 20 White supremacy in its prewar forms was of no use in reorganizing the South’s economic life at the end of the war.Footnote 21 The hasty flight of many slaveholders during the war, the freed people’s expropriation of mules, cattle, and other movable property, their burning of cotton gins, and their deliberate withdrawal of their labor in the more strategic areas of the countryside temporarily smashed the slaveholders’ conception of ownership and their hold over society.Footnote 22

From the vantage point of the ex-slaveholders, the state constitutional conventions of 1867 and 1868 and the new state constitutions appeared to underwrite the destruction of their world.Footnote 23 However, The Union Army’s occupation of strategic areas of the South and the Freedmen’s Bureau’s promulgation of labor contracts only constituted a puny demonstration of the national government’s power.Footnote 24 If the national government was to continue to intervene in conflicts between ex-slaveholders and ex-slaves over land and political participation, it had to restore the alienable nature of private property, while divorcing it from the ownership of human beings. It also had to establish order in the most war-ravaged areas of the countryside.Footnote 25

Caddo’s slaveholders became wealthy during the economic boom of the early 1850s.Footnote 26 Many of these men worked their slaves on rockier and more unforgiving portions of marginal land adjacent to better endowed land in the black belt. But during the Red River’s periodic swelling, scores of plantations could be put under water, thus bringing the movement of people and cotton toward New Orleans to a complete standstill. However, slaveholders continued to purchase land south of Shreveport on an unprecedented scale.Footnote 27 Land purchases of metamorphic uplands or the “buckshot” soil along the Red River’s banks had been made under the assumption that slaves performing gang labor was a certainty for the foreseeable future.Footnote 28 Without the assurance of slave labor purchase of such land would have been a fearful display of poor judgment.

In 1860, the average white landowner in Caddo owned around $1,800 worth of property.Footnote 29 The wealthiest planters, however, men such as A. O’Neil, the Vances, Tom Gilmore and his kin, and E. J. Cummins were twenty times wealthier than the average landowner. By 1870, however, the generality of white landowners had property worth, on average, $500, while the net worth of many of the wealthiest planters had fallen to a little less than $5,000. A labor force unwilling to do the abovementioned ancillary tasks inscribed in the work routine would have spelled disaster for the planters of the backcountry.Footnote 30 That coerced entailed labor on frequently flooded and rocky lands might suddenly be abolished drove ex-slaveholders to murderous distraction. Once a new state constitution of 1868 brought Louisiana back into the Union, the rumor of black insurrection began to loom large in the minds of a growing number of whites.Footnote 31 By 1871, many ex-slaveholders in Louisiana became convinced that a general insurrection of the freed people was imminent.Footnote 32

Confrontations between freed people and former slaveowners in Caddo often had [unresolved] but violent outcomes.Footnote 33 In late July 1868, for example, a little over three months after Louisiana’s new state constitution was ratified in a violent popular election, approximately twenty-five to thirty families of freed people settled at Cross Lake, just north of the town of Shreveport and close to the boundary that separated Caddo from Bossier Parish. Most of the settlement’s people hired their labor to local white planters, while cultivating small plots at the lake’s edge and raising livestock. The removed location and their apparent self-sufficiency aroused the suspicions of the local whites who claimed the Cross Lake was a haven for “vagrants and hog thieves.”Footnote 34

During the first week of August, on the eve of harvesting time for the cotton, a group of local white farmers arrived at Cross Lake, allegedly in search of stolen livestock. A local farmer named Heath led the group. They were determined to inspect every household in the settlement. The local freed people resisted their attempts, and a number of the whites were “beaten unmercifully,” according to at least one newspaper account. Once the conflict began, other whites arrived and the “fight became general.” Perhaps as many as twenty of Cross Lake’s residents were killed or severely wounded.Footnote 35

Eventually L. Hope, the High Sheriff of the parish, arrived and arrested several of the Cross Lake residents and about twenty of a much larger number of local whites. All but six of the whites were discharged. The six were bound over to appear at the next District Court. Neither the District Court nor the Police Jury ever convened. By October 1868, a pervasive current of white violence had made the convening of such bodies virtually impossible. After the August [violence] subsided, the Shreveport South-Western, the ex-slaveholder’s broadside, made the laconic assertion, “It was simply a hog killing affair and the negroes and the hogs got the worst of it.”Footnote 36

The war had emancipated the slaves but left the entire South, particularly upland cotton regions, in thrall to a general state of economic backwardness.Footnote 37 From the commencement of Reconstruction to 1880, cotton appeared to be the touchstone of prosperity, provided it could be cultivated without the threat of violence that characterized slavery. That was precisely the problem, as the events at Cross Lake showed.Footnote 38 The Cross Lake incident had been a moment, when former slaveholders tested their capacities and probed for weaknesses among communities of freed people. Once cotton prices began to fall precipitously, the more sanguine features of cotton cultivation turned into a set of cruel constraints. Violent confrontations like those at Cross Lake became the means by which ex-slaveholders began to build a more coherent postwar identity as property owners.

Seasons of Violence

That a large portion of the region’s potential black labor force remained holed up in communities like Cross Lake caused many larger and more submerged grievances of ex-slaveholders to surface. The Cross Lake pogrom was not entirely unprecedented. It would be followed by the slaughter of more than several hundred freed people just across the parish line in Bossier a month later. As the breaking of the hard, upland soils of Caddo commenced in spring of 1868, the bloated corpses of freed people began to float down the swollen Red River, in plain view of anyone who might have been working the marginally more pliable “buckshot” soils along the riverbanks.Footnote 39 By the end of April, bodies began washing up in the fields themselves. By September, just before the cotton harvest and a month after Cross Lake, several hundred corpses were added to the scores of April.Footnote 40 Between the last two weeks of October and the first week of November 1868, white terrorists murdered and assaulted over two thousand freed people and Republican activists in the Red River parishes. Between the April 1868 election, which ratified the new state constitution, and the presidential election the following November the number of Republican votes cast in Caddo Parish alone went from 2,987 to one.Footnote 41 For the next four years, “midnight raids, secret murders, and open riot” characterized the parishes north of New Orleans.Footnote 42

Caddo and Bossier’s planters massacred several hundred black laborers and tenants, marking a high point of upcountry white violence. Most of the murders and assaults in 1868 took place after gangs of white mercenaries such as the Black Horse Cavalry had driven scores of freed people into the bayous and more isolated areas.Footnote 43 Most were carried out on isolated plantations such as Vanceville, Shady Grove, Hog Thief Point, Black Bayou, Reube White’s Island, and Hart’s Island. The subsequent mass killings were often quite brutal. At Shady Grove, for example, fifteen freed people were murdered, and their decapitated remains left in the middle of the road.Footnote 44 The most notorious killers were ex-slaveholders—the Arnolds, Cummins, O’Neils, Vances, Vaughns, and Vinsons.Footnote 45

By 1872, however, the character of white terrorism in Louisiana was changing.Footnote 46 A year before the infamous Colfax War of 13 April 1873 in Grant Parish, the Red River Parishes, particularly Caddo and Bossier, had become the most violent corner of the most violent state in the United States.Footnote 47 On 13 January 1873, for example, P.B.S. Pinchback, Louisiana’s Lieutenant Governor and Stephen B. Packard, the Attorney General, mobilized the state’s Civil and Metropolitan Guards against a coalition led by Henry Warmoth, the state’s former Republican governor and John McEnery, the Democratic gubernatorial candidate. Thousands of so-called Fusionists and future White League militants fled Louisiana’s cities and towns for the countryside. Once there, they began to foment insurrection—particularly in the Red River parishes and the sugar parishes of central Louisiana. Colfax was the first fruit of their efforts.Footnote 48

The Colfax War claimed the lives of at least a hundred black residents of Grant Parish. Armed whites from virtually all the Red River parishes participated in the violence. The authorities indicted nearly a hundred, but only nine ever stood trial.Footnote 49 Three of the nine were in fact convicted, but a “motion in court” held up their sentencing. The case eventually found it its way to the United States Supreme Court as the United States versus Cruikshank. The failure of the Supreme Court to uphold sentencing effectively nullified the Enforcement Act of 1870.Footnote 50 After Colfax, a significant portion of Caddo’s rural white population enthusiastically welcomed white terrorists from outside the parish. Many would later regret such a decision; but between April 1873 and September 1874, many were poised to join what became known as the “Colfax system”—a rural insurrection against Republican state government under the leadership of the White League.Footnote 51

The defining moment of White League activity in Caddo parish came with the Coushatta Massacre of 31 August 1874 in the adjacent Red River Parish. The Coushatta Massacre, which had begun with a series of assassinations of outspoken African-American Republicans the week before, prepared the ground for a general insurrection throughout the Red River parishes, particularly in southern Caddo and Bossier parishes. On Sunday evening of 30 August, hours after their initial capture, eight Republican officials from Red River Parish were spirited across the parish line and murdered just thirty miles south of Shreveport. Within hours of their deaths, squadrons of armed white men on horseback gathered at various points along the Red River—from Atkins Landing in Bossier to Mooringsport north of Shreveport—in preparation to attack the most prominent black and white Republican officials in the area.Footnote 52 Within several days, the violence in the southern portions of Caddo and Bossier had become a generalized killing spree or “negro hunt.” By mid-October 1874, armed mercenaries from the neighboring parishes, and also Arkansas and Texas, began to arrive in the area. By November 1874, the Seventh Cavalry under Major Lewis Merrill attempted to sweep the southernmost parts of the parish of White League militants. Instead, Merrill’s soldiers wound up burying many of the dead that had been left in the aftermath of the killings. Merrill himself claimed, “Scarcely a negro, and in no instance a negro who was at all prominent in politics, dared to sleep in his home.”Footnote 53

Between 1874 and 1879, anti-black violence in Caddo and Bossier parishes achieved a coherence that had been absent during the violence of 1868. In 1868, ex-slaveholders could only oppose the new state constitution by championing the lost social advantages of slavery—advantages that had been forfeited on the battlefield. However, White League political agitation and violence sought to provide white supremacy with a new set of institutional supports. Its adherents championed the “moral virtues” and “straightforwardness” of rural whites—the “woolhat boys” of much of the movement’s propaganda—over the allegedly corrupt and disingenuous character of city dwelling “carpetbaggers” and “scalawags.” League members also claimed they were only opposed to dangerous African-American males who had been seduced by the easy virtues of the Republicans. In their minds, politically mobilized freed people posed an existential threat.

Part of the violence in Caddo flowed from its demography. About half of the white population of about seven thousand resided in Shreveport, while the other 3,500 lived among a rural black population of almost forty thousand.Footnote 54 Over time black land ownership was also sharply reduced in areas where blacks were the preponderant majority.Footnote 55 Cotton prices actually rose to about $10 per bale, but the planters’ violent policies had caused perhaps a third of their workforce to flee to other parishes or to leave the state all together.Footnote 56

Postwar South Africa

The South African War afforded people of various races and social conditions an opportunity to act upon their conception of a just society, albeit in the midst of terrible carnage and loss.Footnote 57 Rumors were pervasive about the horrifying fate of over thirty thousand Boer and African women and children herded into Lord Kitchener’s concentration camps, or of the allegedly churlish manner of African irregulars and teamsters who drove Boers soldiers out of Mafeking and portions of the northern and western Transvaal during the second half of the war.Footnote 58 There were also those perceived cruel turns of fate that translated into Afrikaners losing land, regaining it, and losing it once again.Footnote 59 In the decades following the war most would discover that the state and the Randlords, the owners of South Africa’s gold mines, had cynically manipulated and then extinguished their aspirations.Footnote 60 Antjie Krog, the celebrated South African journalist, noted that the war had marked the beginning of “a hundred years of attitude” for a significant portion of the country’s white population.Footnote 61

By late 1900, the standing armies of the Zuid Afrikaanische Republiek (ZAR) and the Oranje Vrystaat (OVS) had broken up into mobile bands of guerrilla fighters. As a result, the Transvaal’s countryside was transformed in much the same way that the American Civil War might have transformed the South if Lee and his generals had embarked upon an analogous course of action after the winter of 1864.Footnote 62 The war was supposed to have been a “white man’s war,” but at its conclusion Great Britain had placed over fifty thousand Africans under arms.Footnote 63 Like the American Civil War, the South African War signaled the advent of an industrial era.Footnote 64 By 1897, for example, President Paul Kruger’s South African Republic was the world’s principal producer of gold.Footnote 65

Initially local British officials were extremely reluctant to arm Africans. However, Hurutshe, Baralong, and Kgatla Tswana, whose villages and possessions straddled the border between the Bechuanaland Protectorate (now Botswana) and the South African Republic, grasped the inner logic of the war from the outset. Well before war broke out, both the Kgatla, under their paramount chief, Linchwe, and the Baralong, under Montshiwa, organized several regiments or “cattle guards” equipped with rifles and horses.Footnote 66 When Charles Bell, the Resident Magistrate at Mafeking, refused to supply the Baralong with ammunition for their rifles once war was declared, Motsegare, a Baralong notable, confronted him. Baring his chest to reveal a bullet wound he received during the 1880–1881 conflict with Boer vrywilligers or freebooters over contested farmland, he declared. “Until you satisfy me that Her Majesty’s white troops are impervious to bullets, I am going to defend my own wife and children. I have got my rifle at home and I’ll want ammunition.”Footnote 67

During the five years that followed the war the political consciousness of white farmers and former Boer republican soldiers in the western Transvaal experienced a violent quickening. Lord Alfred Milner’s Reconstruction administration engendered the hatred of rural Afrikaners in several important ways.Footnote 68 Milner hoped to restore the institutional support of white supremacy in the Transvaal with four short-term measures: encouraging greater emigration of English speaking whites to the rural districts; softening up Afrikaners with indemnities dispensed by the Compensation Judicial Commission (CJC) for property losses sustained during the war; resurrecting the ZAR’s 1895 Plakkers Wet, or Squatters’ Law, as an enabling law; and making up for the shortfall in unskilled African labor on the gold mines with indentured Chinese workers. All of these proved to be qualified failures by the time Milner left South Africa at the end of 1905.Footnote 69

Combined with Ordinance 13, which sought to confiscate all the firearms still in African hands, Milner’s resurrection of the Squatters’ Law appeared to belie the war’s conclusion and threatened to provoke widespread African resistance over large portions of the Transvaal.Footnote 70 Because there had been no special police or magistracy to enforce the Squatters Law under the prewar republic, it had been virtually ineffectual. Milner’s Reconstruction administration hoped to transform it into an effective means of limiting African access to productive land. However, in October 1903, rumors about large stores of rifles hidden under cattle pens on African land and Africans refusing to pay taxes were already crisscrossing the region. Many local officials believed the new policies appeared to be nothing short of a recipe for insurrection.

South Africa’s backlands also threw up daily instances of postwar African contestation like this one from the Pilanesberg portion of Rustenburg in 1904: “…a farmer told me that he was working on his land, putting in tobacco, and he saw some natives passing at the end of his land. As he wanted labour he went up to them and offered 2s. 6d. a day to work for him, but they simply turned round to him and said ‘If you would like to work for 2s.6d. a day, baas, we shall be only too pleased to employ you.’”Footnote 71

More ominous still was the flood of rumors about armed Africans coming to plunder livestock and movable property spreading among white farmers farther south in the Mezeg/Enselberg region of Marico. The CJC testimony of Marthinus Lezar, farmer and former Boer guerrilla from Zeerust, is instructive. Lezar’s farm abutted the lands of the Hurutshe notable Chief Gopani. Lezar claimed that armed African irregulars under Gopani and British troops under the command of General Carrington had looted his farm in June 1900 and again in August of the same year. Upon his release from prison at Green Point near Cape Town, he demanded £260 compensation, which he did not receive. As late as June 1903, Lezar complained that Gopani’s people were threatening his person and his property.Footnote 72

Racializing the “Westminster Model”

Milner and Lord Lyttleton, the British Colonial Secretary, believed that rural Afrikaners would either embrace the new order or, at the very least, cease to be a political threat. From their vantage point, white supremacy was to be secured under permanent Crown Colony status—which entailed a limited constitution, an electorate composed of the propertied white adult male population irrespective of “race”—the “elective element” in so much of Milner and Lyttleton’s correspondence—and a ready use of the Imperial Army to quell civil disturbances or African unrest.Footnote 73 Of course, Milner hoped that English speakers and Anglophiles would run future administrations.

Milner and officials in his inner circle or “kindergarten” often overstated the success of forging a connection with rural Afrikaners. Such overstatement grew out of Milner’s tendency to oversimplify the aspirations of rural Afrikaners. The offhanded but frequently used designation of rural Afrikaners as “Brother Boer” was merely a cynical expression of the dearth of collaborators in the countryside. By the beginning of 1904, it had become an exercise in self-deception.Footnote 74 Nothing demonstrated Afrikaner disaffection with Milner’s administration more than the Compensation Judicial Commissions’ decisions.

Consider David Christiaan Christophel van der Linde’s September 1902 petition. Van der Linde claimed over 353 British pounds in compensation for the loss of one wagon, four donkeys, one horse, his 1901 and 1902 maize crops and £20 worth of “sundries” from his Buffelshoek farm in the Boschveld Ward of Marico. The farmhouse itself had also been burnt to the ground. Van der Linde was variously a carpenter, blacksmith, and merchant of dry goods, as well as a farmer. He claimed that “furniture, clothing, tools, etc. [the “sundries” of the earlier portion of his petition] were either burnt or “taken away by armed Kaffers” under the command of Generals Methuen and Douglas. David Roux, who owned the neighboring Palmiefontein farm, and Hendrik Vivier of Zeerust, testified on van der Linde’s behalf. Four years later, on 26 October 1906, van der Linde’s estate and heirs were awarded £40—over £2 in “recoveries” and £38 in cash (he had died two years after his initial claim).Footnote 75

Subsequent claimants and witnesses maintained that African irregulars had turned the farms of Marico’s Bergvliet region into an informal commissary between September 1900 and July 1901. Frederich Petrus van der Merwe, the seventy-two-year-old owner of Boschvliet farm, claimed that African irregulars from nearby Dinokana had done over £137 worth of damage to his farmhouse and a smaller “roundhouse.” According to van der Merwe, the Africans stripped the buildings of their moldings, doorframes, doors, and windows. Frederich’s kinsman, Petrus R. van der Merwe, who owned the neighboring farm Hartbeestlaagte, claimed these same Africans had removed a “plow, 12 draft oxen, 13 large cows, 6 heifers, 10 calves, 2 buckets of brandy and a harmonium.” Petrus, Albertus Jacobs of the farms Bergfontein and Rietgat, and Johannes Petrus van der Merwe, a younger kinsman who had recently surrendered and signed a loyalty oath, claimed they fired on the alleged looters to no avail. Jacobs also claimed that he and the other men “followed the spoors [trails] of the assailants but could not capture them.” All four men claimed that each of them had lost more than £700 of property during the raid. Jacobs claimed that he had seen some of his movable property and livestock at Chief Gopani’s location in Dinokana after the war.Footnote 76

The CJC did not honor any of the claims in full, since it was obvious that most of the Afrikaners who shot at and pursued the African irregulars that had allegedly looted their farms had been on commando at the time. The aged Frederich van der Merwe and young Johannes Petrus were possibly the only exceptions. Like their brother-in-law and uncle, Abraham Lee, who owned Mezeg and Olifantsvlei farms, which British troops under Generals Carrington and Methuen had looted and burned during the closing phases of the war, most of the younger van der Merwe men had only surrendered to British authorities on 9 June 1902 at Waterkloof.Footnote 77 What began as a trickle of accusations about connections between farmers who had signed loyalty oaths and guerrillas still in the field in November 1901 now became a torrent of rumors, innuendos, and verifiable information at the end of the war.

Numerous reports, with many pages underlined in red ink, wound up in the Provost Marshal’s and military intelligence’s dossiers. Much of this material found its way into the deliberations of the juries or review boards of the CJC, ensuring that compensation would be a mere pittance of what the petitioners had requested. These extremely leveraged cases often became highly charged instances of political theater: while the plaintiffs offered elaborate and detailed explanations of their losses, the heavily underlined intelligence reports would be circulating among the members of the jury or review board.Footnote 78 These rural Afrikaners were now attempting to make their claims as farmers whose private property had either been confiscated or destroyed during the course of the war, but the officials of the review boards and the postwar state also saw them as ex-combatants, some of whom were reputed to be absolutely irreconcilable to British rule. Upon capture, many men from these extended families were described in subsequent British intelligence reports as “bad characters,” “wanted for murder,” “will undergo criminal prosecution after the war.” Virtually all of them were earmarked as potential enemies of the postwar state.Footnote 79 Ten years later the living members of these households joined the failed 1914–1915 white rural rebellion. A local black eyewitness to the rebellion stated, “…our employers told us to leave the job because the war had started.… Actually, the whole thing started in 1902. It started to simmer in 1902 and ultimately broke out in 1914.… There was confusion and you could not walk during the night.”Footnote 80 The descendants of these households would also become active in the extreme Afrikaner nationalist movements that culminated with apartheid government of D. F. Malan in 1949.

Rumors and Rifles, 1902–1905

Nearly fifty thousand Africans were still under arms in the Transvaal after the war. British forces, fewer than two hundred thousand men, were scattered over all four provinces of South Africa. British officials estimated that vanquished Boer forces were somewhere between fourteen and twenty-one thousand men. Kitchener and his staff claimed that many of the vanquished Boer guerrillas remained under arms. Meanwhile Lloyd George also continued his tirade about the potential danger of armed Africans. A stream of intelligence reports from all over the Transvaal described how detachments of armed Africans controlled movement along the roads of the backlands, seconding Lloyd George’s claims.Footnote 81 Consequently, Milner’s government hastily promulgated Ordinance 13 of 7 August 1902.Footnote 82

The ordinance saddled resident magistrates, the South African Constabulary (SAC), and native commissioners with the collection of tens of thousands of rifles.Footnote 83 Ordinance 13 stipulated that all rifles in the hands of former African irregulars, including those they had purchased, were to be turned over to government officials on pain of a fine and a year of imprisonment with hard labor.Footnote 84 Headmen and chiefs were exempted.Footnote 85 There were only two hundred SAC posts in the Transvaal and Orange River Colony (the former Orange Free State) with approximately ten thousand officers, patrolmen, and auxiliaries.Footnote 86 By October 1902, the most seasoned British soldiers were already on their way back to Great Britain or India.Footnote 87 As a result of being understaffed, native commissioners and SAC constables sought to bypass law and custom whenever they threatened to impede the impounding of rifles.Footnote 88

Difficulties associated with the skewed relations of force in Rustenburg and Marico surfaced well before the promulgation of Ordinance 13.Footnote 89 The tone of discussions about the African labor supply, for example, fluctuated between sunny confidence and dark foreboding toward the end of 1902. Magistrates and native commissioners were strapped with the unenviable task of informing armed Africans that their condition was to remain essentially the same despite their near revolutionary impact on the war.Footnote 90

In the process of doing their duty, many of these officials had to engage in embarrassing reminiscences of the closing phases of the war. Many native commissioners were former SAC and Field Intelligence operatives and were, therefore, attempting to limit the scope of potential conflicts between themselves and their former African comrades-in-arms while also deliberating on actual disputes between reinstated Boer landlords and these same Africans.Footnote 91 Consequently, Ordinance 13 did in fact speed up a shift in official thinking but not without a complementary set of difficulties.Footnote 92

Milner’s government also chose not to recognize the destructive impact that the war’s devastation and capital accumulation in the mining industry would have on rural whites in the Transvaal and elsewhere, even on those who appeared to be holding their own at the close of the war.Footnote 93 Many of these difficulties were obscured by the quirk-laden policies of Major General R.S.S. Baden-Powell, the founder of the South African Constabulary (SAC). Baden-Powell began to mold the SAC into a separate armed force after October 1900, six months after he had botched the job of preventing Boer guerrillas from moving back and forth across the Magaliesberg mountains. Failure proved no obstacle to Baden-Powell’s estimate of his importance.Footnote 94

At close of the war, once the state’s immediate enemies had become its wartime African allies, Baden-Powell speculated on the SAC’s future role while touring various districts in the Transvaal:

It is very interesting travelling like this, seeing my organization … starting work—It is like starting a big engine that nature made and going about with an oil can and wrench making various parts work easily and effectively. We are putting the burghers back on the farms and running the postal service, doing customs work, as well as the ordinary police work in town and country, and detective and secret service duty. So there is lots to think about—but I think we are all of us earning our pay.Footnote 95

Baden-Powell’s inability to make a distinction between his fantasies and what was actually happening made pinning down the distribution of firearms in Marico and Rustenburg even more difficult. Also, disgruntled SAC constables occasionally sold rifles to Africans and white farmers alike, either because they were strapped for cash or because of lingering morale problems between officers and constables. Both causes reinforced each other in many instances. Constables from Commonwealth countries such as Australia and Canada preferred to be commanded by officers from their former combat units. When such arrangements proved impossible, minor infractions such as departing from the dress code, failing to turn out on parade, or disagreements over grade or pay often cascaded into near mutiny.Footnote 96

SAC units continued to be supplied with wartime amounts of ordnance after the war ended. Constables readily exchanged surplus rifles and ammunition for liquor and other items. For their part, even the most loyal and law-abiding Afrikaner farmer participated in these transactions. They believed that Milner’s Compensation Judicial Commission (CJC) boards had egregiously traduced them. They also believed that they were in imminent danger of attack from truculent Africans.Footnote 97 Many also reasoned that if a constable would sell them a rifle for a jug of mampoer or home-made spirits, what would that same constable give for an ox or cow offered by an African peasant.Footnote 98

After some skittish moments, the confiscations went forward. The expected African insurrection never occurred. Donald Rolf Hunt, the Sub-Native Commissioner at Rustenburg, described such efforts in breezily optimistic terms in October 1902: “Our disarmament of the Transvaal natives is going off very nicely and without trouble or fuss. We have got 30,000 rifles of all sorts in and expect altogether 42,000. We pay £3 and £4 per rifle (whatever old gaspipe it may be) but if you think it out you will see it is worth the expenditure. The native loves his old gaspipe as much as a new Mauser or Lee Mitford. If we get ’em all in, the farmers will be easier in mind and altogether everyone will breathe more freely.”Footnote 99

The disarming of African irregulars did threaten to precipitate a revolt, but not for the apparent reasons. Hunt stumbled on part of the reason five months later, in March 1903, on a tour of the neighboring district of Lichtenburg, for which he also had some administrative responsibility:

There seems every possibility of a small famine in the Western Transvaal and Bechuanaland this year. The crops have failed owing to no rain and there is precious little water at the best of times. My poor wretched natives will suffer worst of all. The price of Kaffir Corn (sort of millet) has gone to double what it ought to be. I have told every chief and headman to send his young men to earn money and save it to buy food with. The Dutchmen are fed by Repatriation, but it means that Repatriation will have to go on possibly for an extra year at your expense, not Johannesburg’s.Footnote 100

Increased African tax rates followed swiftly behind drought and cattle diseases. Predictably, the tax increase came after officials thought they had confiscated a large number of rifles. Even the most prosperous peasant families were forced to oversell grain or to work for wages in 1904 and 1905.Footnote 101

African discontent over the increased tax rate reinforced a common belief among the white population that the country’s prosperity had been compromised by Africans refusing to work for wages. G. G. Munnik, a former landrrost from the Zoutspansberg district and Minister of Mines for the former South African Republic (ZAR), put the grievances of rural Afrikaners in poignant if overstated terms during his 1905 testimony before the South African Native Affairs Commission (SANAC):

In the last two or three years, first of all there was the war, when they [rural Africans] did not cultivate much, then followed two years of drought; what became of them then?—I will tell you. During the war the Native earned very high wages. Not only did he earn high wages, but he looted everything he could get his hands on; whether it was a bedstead, or whether it was a coffee pot, he stole it and took it home…; and that is why there has really been a scarcity of labour, because he has been looking after all this stolen stuff.Footnote 102

Magistrates, native commissioners, and SAC constables confiscated nearly forty thousand rifles from Africans in the Transvaal by the outset of 1903—ten thousand from the eastern Transvaal and another thirty thousand from the northern and western regions of the new Crown Colony. But even if one accepts the most conservative estimates of the number of rifles distributed to Africans during the war, another ten thousand rifles remained outstanding.Footnote 103 Why was the SAC so convinced of the commonsense conclusion that all arms held by Africans in the two districts had been confiscated? Where were the rest? Did the anxieties and complaints of white farmers in places such as Bergvliet and Saulspoort, areas where armed African resistance to the commandos had been well-organized and formidable, amount to a reasonable set of precautions?Footnote 104

Meanwhile native commissioners were ordered to confiscate even more land, movable property, and rifles from Africans. But since the new policies were insufficient inducements for Africans to obey the King’s writ voluntarily, such officials were also encouraged to draw upon the armed power of the military and SAC in order to humble African smallholders and tenants.Footnote 105 Despite their hatred of Milner’s Reconstruction Administration, Afrikaner farmers welcomed the SAC’s assistance in reasserting their property rights over the aspirations of black South Africans.Footnote 106 However, white landowners were not entirely satisfied with police assistance for obvious reasons: less than a year before the SAC units had been charged with the relentless pursuit of many of the farmers it was now charged with protecting.Footnote 107 Moreover, despite the SAC’s intervention and confiscation of African weapons and movable property, white farmers persisted in believing that pockets of armed Africans existed in the two districts. Such beliefs powerfully influenced the tenor of relations between landlords and peasant tenants.Footnote 108 The SAC also found itself either shorthanded in the most troublesome areas of the Transvaal or so immersed in enforcing of labor contracts that its district commandants did not always see the connection between the enforcement of Ordinance 13 and recalcitrant mood of African tenants and laborers.Footnote 109 The machinery of surveillance and repression that would plague African peasants and labor tenants for the rest of the twentieth century was getting into gear in the countryside.Footnote 110 However, the disarming of Africans in Rustenburg and Marico presented its own set of problems and difficulties for various white governments up to the 1932 depression and the promulgation of the Native Contract Law, the ancestor of apartheid legislation.Footnote 111

Conclusion: Stipulating the Terrain of Freedom

What might African American and black South African responses to the violent prelude to segregation teach us about the paradoxes of nineteenth-century economic liberalism? Did coercion and terror in fact have limited “marginal utility” at moments when the two societies were experiencing rapid and indelible changes in agriculture and industry? How did longstanding traditions of violence in the countryside prepare both countries for the institutionalization of segregation?

The violence of 1868 in Caddo Parish was carried out by the ex-slaveholders themselves and former Confederate cavalrymen who, after having formed a series of mercenary bands just across the state line in Texas, put them at the disposal of ex-slaveholders.Footnote 112 It aimed to prevent local freed people from withdrawing their labor from the plantations. By the 1870s, however, the White League were in place in the Red River Parishes. Violence against communities of freed people was politically informed and deliberate. There was a political campaign to incite the entire rural white population against the freed people’s desire for greater political participation and access to productive land, which came to be billed as a threat to the white well-being.

The ex-slaveholder’s claim that the freed people were spearheading a general insurrection in the state had very little currency before 1874. However, the precipitous decline in cotton prices in 1874, and again in 1878, accentuated the growing indebtedness of many hardscrabble white farmers who had been compelled to grow cotton if they wanted to maintain some shred of personal economic independence.Footnote 113

By the 1880s, one-third of all tenant farmers who produced cotton in the South were white.Footnote 114 But how many such people in Caddo had once owned their own land, on which they had been content to grow what they pleased before 1870? These men took little comfort from the rough equality of wages and remuneration for growing cotton throughout the South for whites and blacks in the 1880s.Footnote 115 Indeed, if they were in a position to make such a comparison, and some of them obviously were, it would have been the source of profound personal shame and thus sufficient cause for them to participate in ongoing instances of anti-black violence.Footnote 116

Boer landowners in Rustenburg and Marico sought compensation for the seizure and destruction of substantial proportions of their property by African irregulars and British counterinsurgency units such as the South African Constabulary (SAC) and Imperial Light Horse (IHL). By means of their public testimonies at the Compensation Judicial Commission (CJC), they sought to reinterpret the most violent moments of the closing phases of the war as a series of instances in which they had saved white civilization from destruction by the barbarous acts of armed African irregulars—those who Jan Smuts had described as the “Frankenstein monster created by fatuous policy.”Footnote 117 But the public testimonies of Boer landowners were also self-incriminating and confirmed the postwar government’s provisional conclusion that a large swath of the rural white population of the two districts remained irreconcilable to the prospect of British rule.

Until the 1932 Depression and drought, British officialdom and well-off Boers or Afrikaners liked to delude themselves that the protracted conflict between Boer and Briton was a “race question.” The illusion was inscribed in official government and public proceedings, except during moments of “Swart Gevaar,” or “Black Peril”— times when African men were frequently accused of raping white women and threatening insurrection.Footnote 118 The alleged rapes were taken as avatars of impending black insurrection. The rise of a proto-fascist nationalist movement among Afrikaners between 1926 and 1948 broke the spell of the Anglo-Afrikaner “race” illusion.Footnote 119

Getting to the root of political violence in South Africa and the American South requires a healthy dose of skepticism about the apparent certainties of the master narratives of collective violence in both societies, especially since low-intensity racial violence continues to plague both countries. Indeed, these master narratives must now be reassessed in relation to the micro-history of local struggles and their discursive meanings. As James Scott suggests, economic and political conjunctures often create desires and aspirations among otherwise marginal protagonists that the state cannot easily cater for or even anticipate.Footnote 120

Even though the most apparent features of South African apartheid and American segregation are receding, a great deal of confusion remains about whether both were coincidental misfortunes or deliberate instances of social engineering. This confusion turns largely on a misunderstanding of how violence of a collective and intrapersonal sort assisted in maintaining the social order in the past.Footnote 121 Freed people in the United States and African peasants and laborers in South Africa exercised real tactical social power for two brief incandescent moments. And while they could not temper the violence of their societies after two devastating wars, they could dispute the meaning of the concepts—private property, free labor, liberty, and civic participation—that were claimed to justify white violence.