I. Introduction

This article examines Confucius’ ideas of moral peace or feeling-at-home (an 安) and moral pleasure (le 樂) in the Analects. An and le are two correlated aspects of a self-cultivated state of being (jing-jie 境界) that is grounded on the practice of human-heartedness (ren 仁),Footnote 1 i.e., be true to oneself and be benevolent to others, and on the following of the Way (dao 道),Footnote 2 i.e., walking on the right path of life. Moral peace and moral pleasure involve not only one's reason (i.e., knowing ren and dao) and one's will (i.e., willing ren and dao), but also one's love or ‘emotional liking’ (hào 好) with respect to the practice of ren and dao. Once reached, this state of being is autonomous (rather than heteronomous), self-fulfilling, and without moral anxiety or guilty conscience; nor is it interrupted by ordinary feelings of worry (you 憂 and huan 患). The uniqueness of Confucius’ ethical state can be shown by distinguishing it from physical pleasure or mental happiness (pleasure, kuai-le 快樂; happiness, xing-fu 幸福), likening it to Kant's idea of intellectual contentment in respecting the moral law, and pace Philip Ivanhoe's recent interpretation of Confucius, contrasting it with Aristotle's concepts of pleasure and eudaimonia.

II. Moral peace: Feeling-at-home (an 安)

The Chinese word an appears in the Analects 15 times in nine different sections,Footnote 3 but the most philosophically significant use of it occurs in several passages (2:10, 4:2, 17:21) where an indicates a state of feeling-at-home that closely relates to Confucius’ understanding of ethical cultivation. At 2:10, Confucius suggests that where people feel at home in their actions and choices is where one would observe their true personalities: “The Master said, ‘Watch what people do, observe what they follow, examine in what they feel at ease (suo-an 所安). How can they conceal? How can they conceal?’”Footnote 4 People may feel at ease in what? According to QIAN Mu's (錢穆, 1895–1990) commentary on 2:10, they may feel at ease in doing things out of their own will that also makes them feel settled and pleasant:

Where it is that one feels at home: feeling settled (an-ding 安定) and feeling peaceful and pleasant (an-le 安樂). If one is forced to do something, one does not feel settled or pleasant, and one is prone to change from what one is forced to do. In contrast, if one feels pleasure in doing something, never feels tired of doing it, one feels settled and does not want to change. ‘Feeling-at-ease’ here refers to a mode and bearing of behavior. (QIAN, Reference QIAN2006, p. 36, my translation)

On the surface, “feeling-at-ease” (home) here seems merely a psychological state, not directly or explicitly linked to ethics. But this does not mean that it is only psychological in the Analects, for at 17:21 the same state is understood as internally linked to ethical cultivation. Confucius discusses with his student ZAI Wo whether the latter feels at home and should feel at home with eating sweet rice and wearing brocade gowns after the first year of mourning for his parent, given that the conventional mourning ritual was three years. When ZAI Wo said he felt at home doing so, Confucius first responded with a go-ahead, but then blamed him for lacking human-heartedness (ren 仁). Confucius implies that an authentic feeling-at-home, without moral anxiety or guilty conscience, must be grounded on human-heartedness, and that ZAI Wo's self-claimed feeling-at-home would not be counted as authentic feeling-at-home (see LI, Reference LI2017).

The ethical nature of feeling-at-home becomes even more evident at 4:2 where Confucius explicitly grounds it on human-heartedness:

The Master said, “Those who are not human-hearted can neither stay long in privation [yue 約], nor stay long in enjoyment [le 樂]. Those who are human-hearted are at ease [an 安] with human-heartedness, and those who are wise profit from human-heartedness.”

It is significant that being “at ease” here is discussed in connection with both le 樂 and human-heartedness. The word le appears ambiguous and may be understood as a moral pleasure or as an ordinary pleasure or enjoyment — due to being well-off as opposed to being in want (yue 約).Footnote 5 On the latter understanding, those without human-heartedness would not enjoy ordinary pleasure for long, because lacking moral standards, they would quickly destroy whatever pleasure was available to them. (For example, without following proper social order, even the pleasure of eating is not possible: 12:11.) On the former understanding, those without human-heartedness would not be able to constantly stay in moral pleasure while facing adversity, in contrast with those who, like YAN Hui, practise human-heartedness and stay in moral pleasure without change — even in dire poverty (6:11) (More on this in Section III.)

Thus, for Confucius, an authentic feeling-at-home (an 安) must be anchored in human-heartedness (an-ren 安仁). At 2:10, Confucius suggests that a good way to know the true character of a person is to examine where he feels at home, which seems to imply that one might feel at home in doing different things or in pursuing different goals. However, at 17:21 and 4:2, he makes it clear that, regardless of occupations or activities, there is only one way to feel at home, that is, to feel it in practising human-heartedness. Indeed, it is very doubtful that he would count any other way of feeling at home as being authentic (for example, a possible ‘feeling-at-home’ with glib speech or superficial appearance, would be seen by him as signs of not being human-hearted. see 1:3). As stated above, at 17:21, Confucius blames ZAI Wo's self-claimed ‘feeling-at-home’ because it is not based on human-heartedness and thus not the authentic feeling-at-home he envisions.Footnote 6

III. Moral pleasure (le 樂)

The word le occurs 21 times in 14 different passages in the Analects,Footnote 7 but Confucius’ signature use of it appears in 6:11 and 7:16, where he discusses his and his student YAN Hui's experience of a special kind of pleasureFootnote 8 in which one is not disturbed or bothered by poverty.

The Master said, “Worthy indeed was Hui [YAN Hui]! With a bamboo holder of food, a gourd ladle of drink, and living in a narrow alley, while others could not endure the distress, he did not allow his pleasure (le 樂) to be affected by it. Worthy indeed was Hui!” (6:11)

The Master said, “With coarse food to eat, plain water to drink, and my bended arms for a pillow, joy [le] can be found in the midst of these. Wealth and prestige acquired in inappropriate ways are no more than floating clouds to me.” (7:16)

At 6:11, YAN Hui, Confucius’ cherished disciple, does not take pleasure in living in a narrow alley with a bamboo holder of food, a gourd ladle of drink. He does not intentionally choose to live in such a condition, nor does he believe it to be in any way optimal. Similarly, at 7:16, Confucius’ pleasure is not literally eating coarse food and drinking plain water, having his bended arms as a pillow. If possible, both YAN Hui and Confucius would prefer to live under better conditions. What Confucius wishes to avoid is the improper attainment of “wealth and prestige,”Footnote 9 which, in his view, disrupts his pleasure.Footnote 10 What disrupts this pleasure also disrupts the corresponding peace (feeling-at-home, an), because the states of an and le understood in the Analects are two sides of the same coin.Footnote 11 They are not two temporarily separate states, one prior to another, nor are they causally linked. In putting an-le together, I do not treat it as a compound with a modifier (an) and the modified (le); rather I interpret them to express equivalent ideas but with different emphases. An stresses an optimal moral state of being (involving both actions and emotions), feeling-at-home, the absence of moral anxiety or moral perturbation (9:29, 14:28, 12:4), and le highlights the moral pleasure, the self-contentment in doing what is right, analogous to the harmony with one's self, rather than an obtainment of something outside oneself. The lack of moral anxiety, however, does not mean a care-free, indifferent, or apathetic attitude toward virtues, the Way, or others, but rather it clears up the ground for these genuine moral concerns (7:3, 15:32, 4:21, 17:21).

What exactly is the nature of Confucius’ (or YAN Hui's) pleasure that is possible even in poor and challenging conditions? According to LI Zehou's comments on le at 7:19, “the primordial source of Confucius’ pleasure lies in shaman mystical experiences, i.e., the ecstasy one enjoys when one is in total enchantment with everything in the world” (LI, Reference LI2015, p. 137, my translation). This interpretation, as plausible as it may sound, seems vague and even un-Confucius-like. Confucius’ pleasure might be traced back to some shamanic mystical experiences, but we may have to ask what “total enchantment” consists in — practically or morally — for Confucius and YAN Hui. After all, Confucius and YAN Hui at 6:11 and 7:16 were not engaging in any form of shamanic trance. If so, that would be against Confucius’ general rational and keep-it-at-a-respectful-distance attitude toward gods, spirit, and praying (6:22, 11:12, 7:35). Thus, in order to clarify this special pleasure, we must examine the (non-shamanic) ground on which it is based (which will take up the rest of this section) and study its concrete manifestations.

One way to understand this pleasure is to base it on the practice of human-heartedness. This is clear in the general connection between pleasure and human-heartedness at 4:2 discussed above, but also evident at 6:7 particularly regarding YAN Hui's pleasure, which manifests itself in his not straying away from human-heartedness for a relatively long period.

The Master said, “Hui (YAN Hui) is able to maintain his heart-mind not to deviate from human-heartedness for three months. The others are only able to maintain this for days or a month.” (6:7)

Such steadfastness in holding onto human-heartedness explains YAN Hui's ability to remain constant in adversity and thereby enjoy enduring pleasure (6:11).

Another way to understand Confucius’ pleasure is to link it to the following of the Way. “The Master said, ‘To like something is better than to merely know about it, and to take pleasure in (doing) it is better than to merely like (hào 好) it’” (6:20, my translation). Here the word “it” is commonly interpreted as referring to “the Confucian Way” (see Edward Slingerland's comment added to his translation of the passage, Slingerland, Reference Slingerland2003, p. 59; also see LI, Reference LI2015, p. 116), but it can equally refer to human-heartedness. Notice that to “know about it” does not imply a motivation to act on it; to “like (hào 好) it” indicates a motive or desire but does not necessarily lead to an action.Footnote 12 Only when one “take[s] pleasure in (doing) it” can he or she synthesize to “know about it” and to “like it” and realize both in practising it.

Despite the apparent distinction between grounding this pleasure on human-heartedness at 6:7 and grounding it on the Way at 6:20, there is strong evidence in the Analects that these two groundings are compatible and indeed interpenetrating. They belong to the same ethical endeavour, albeit with different emphases. The Way is the way to practise human-heartedness and human-heartedness must be practised by walking on the Way, the only difference being that human-heartedness highlights the inner (subjective, spontaneous) basis and the Way stresses its outer (intersubjective, regulative) manifestations. At 7:6, “The Master said, ‘To aspire after the Way (dao 道), hold firm to virtue (de 德), lean upon human-heartedness (ren 仁), and wander (you 游) in the arts (yi 藝).’” The expression “to aspire after the Way” aims at a goal and the way toward it. The expression “lean upon human-heartedness” presupposes a base of an internal, autonomous nature,Footnote 13 i.e., carrying out all things with a good will (zhi 志) (see 4:4). The interpenetrating nature of human-heartedness and the Way is echoed again at 4:5:

The Master said, “Wealth and prestige are what people desire. If they are not obtained in the proper way (dao 道), they should not be held. Poverty and low status are what people dislike. If they are not avoided (de 得) in the proper way, they should not be avoided (qu 去). If exemplary persons abandon human-heartedness (ren 仁), how can they deserve that name? Exemplary persons do not, even for the space of a single meal, go against human-heartedness. In moments of haste, they are with it. In times of distress, they are with it.”

Never for a moment should an exemplary person go against human-heartedness, nor for a moment should he or she walk away from the Way. All choices and actions, whether about things we want, for example, wealth and prestige, or about things we hope to avoid, such as poverty and low status, must be based on the higher standards of human-heartedness and of the proper Way.Footnote 14 Thus, for Confucius, practising human-heartedness and following the Way are what make humans distinctively human; they constitute the very purpose of authentic human life. Those who sincerely seek human-heartedness would go even so far as sacrifice their lives to accomplish it (15:9). The point is powerfully echoed by Mengzi when he states that to abandon human-heartedness and the Way is to do violence to one's very self and to throw one's person away, namely, to fail to live up to how one ought to live:

With those who do violence to themselves, one cannot speak, nor can one interact with those who throw themselves away. To deny propriety and rightness in one's speech is what is called “doing violence to oneself.” To say, “I am unable to abide in humaneness or to follow rightness” is what is called “throwing oneself away.” For human beings, humaneness is the peaceful dwelling, and rightness is the correct path. To abandon the peaceful dwelling and not abide in it and to reject the right road and not follow it — how lamentable! (The Mengzi, 4A10, also see 7A33, Irene Bloom's translation, 2009)

In aspiring after the Way and leaning upon human-heartedness, one's life becomes purpose-driven and is grounded on a solid foundation. The purpose is not an external one imposed from the above (God) nor from the external (the state), but flows from one's own base and efforts (15:29). This purpose-driven life is a harmonious operation where one knows what one ought to do, where one wills to do it at all costs and with no regrets (7:15, 4:8), and where one takes pleasure in doing it. The pleasure contains both an intellectual aspect — an intellectual liking, being content with doing what one ought to do — and a dispositional aspect, i.e., an emotional liking, hào 好, as if one is being naturally attracted to it. The emotional engagement here is very important, because just as the authenticity of mourning lies in the genuine emotion of sorrow (ai 哀) (3:26), the authenticity of the purpose-driven life also resides in a genuine moral pleasure (le 樂).Footnote 15 In QIAN Mu's words quoted above, one would “enjoy doing something, never feel tired of doing it” and “feel settled and not want to change,” despite adverse conditions and negative consequences.Footnote 16 In Confucius’ words, one would be as “tranquil” as “mountains” (6:23).Footnote 17

IV. Concrete expressions of Confucius’ pleasure

What is it like to have Confucius’ pleasure? To begin with, those who have this pleasure do not have moral anxiety,Footnote 18 i.e., they do not suffer from a guilty conscience. “The Master said, ‘The wise are free from perplexity, the human-hearted are free from anxiety [bu-you 不憂], and the courageous are free from fear’” (9:29). Here the word “anxiety” (you 憂, together with perplexity, huo 惑 and fear, ju 懼) is used as an intransitive verb. Bu-you does not have a specific object about which the human-hearted do not have anxiety.Footnote 19 The idea is further elaborated at 12:4: upon reflection the human-hearted realize that they have inner peace (feeling-at-home) and they have no moral regrets and no guilty conscience.

Sima Niu asked about being an exemplary person. The Master said, “An exemplary person is free from anxiety and fear.” Sima Niu said, “Being free from anxiety and fear — does this constitute an exemplary person?” The Master said, “If upon internal reflection you find nothing to regret [bu-jiu 不疚], what is there to be anxious about or to be afraid of?” (12:4)

For Confucius, there is only one thing that exemplary persons should feel anxiety about or be afraid of,Footnote 20 and that is if they hold their own person and keep it intact — or more specifically, if they practise human-heartedness and follow the Way (15:32). This is why Confucius believed that BO Yi and SHU QiFootnote 21 would have no regret: they pursued human-heartedness and they attained it (7:15). When exemplary persons have no ethical regret, there is nothing about which they should be ethically anxious about or afraid of. External challenges and hardship may test them, disturb them, and frustrate them, but would not count for them as (ethical) suffering; this is why Confucius was not bitter toward Heaven nor did he blame others when no one seemed to understand him (14:35). No external conditions or contingencies can reduce the value of their person, nor can these reduce their pleasure in practising human-heartedness and following the Way,Footnote 22 but can rather give them opportunities to prove it and elevate it (also see Olberding, Reference Olberding2013, pp. 434–435). This is why — and LI Zehou is after all right in his comments quoted above on Confucius’ pleasure at 7:19— they can be at peace with themselves and with everything around them. In Confucius’ case, even facing the impending end (final years) of his life does not register in his consciousness. So immersed in the pleasure was he in the pursuit of the Way that he even often forgot to eat (7:19).

To further illustrate the point, let's look at the idea that Confucian exemplary persons do not worry about being deprived of brothers.

Sima Niu lamented, “Everyone else has brothers. I alone have none.”Footnote 23 Zixia said to him, “I have heard that ‘Death and life lie in destiny (ming 命), wealth and honor depend upon heaven.’ Exemplary persons are reverent and not careless, and they treat others with respect and observe ritual propriety. All within the four seas are their brothers. Why does an exemplary person have to worry about having no brothers?” (12:5)

To treat others with respect and to observe ritual propriety is to practise human-heartedness and to follow the Way. Thus, what exemplary persons ethically ought to do is done. The fact that they may have no biological brothers or even if they have but none live close by is no reason for them to worry, since in holding their person, in practising human-heartedness and following the Way, they turn all within the four seas into their brothers.

It is important to stress, however, that Confucius’ pleasure does not come as a natural endowment without effort, nor is no effort needed in order to treat everyone within the four seas as one's brothers. It all comes from a conscious resolution to practise human-heartedness (including the respect of others, etc.), to follow the Way, so that one can turn the external conditions around rather than being turned around by them.Footnote 24 It all comes from doing what one can do and should do in a life-long commitment (12:1, 8:7).

V. Confucius’ peace-pleasure (an-le) vs. Kant's intellectual contentment

To further clarify Confucius’ peace-pleasure, let's put it in a cross-cultural context with comparable ideas to be found in Aristotle and Kant; the latter, I argue, is closer to Confucius in terms of maintaining the autonomous nature of ethics. The present section compares Confucius’ peace-pleasure with Kant's idea of intellectual contentment in respecting the moral law, and the next section contrasts it with Aristotle's pleasure and eudaimonia.

According to Confucius, people in a state of peace-pleasure do not have feelings of moral guilt or self-reproach, despite the challenges and frustrations they may experience in doing what is right. This focus on the absence of feelings of guilt and self-reproach may lead some to the conclusion that Confucius construed peace-pleasure only in negative terms. However, this would be a hasty conclusion, in that Confucius also viewed peace-pleasure in positive terms as part and parcel of a purpose-driven, self-fulfilling process of doing what one ought to do. It is an ethical ideal that — regardless of all other contingencies in life — everyone ought to pursue and can pursue. And the pursuit itself consists positively in a state of contentment with one's very existence, and as such it is self-rewarding. In this sense, it is comparable to what Kant calls “intellectual contentment” or “self-contentment,” an ethical state arrived at when one respects the moral law, which is in one sense negative but in another sense positive.

Have we not, however, a word which does not express enjoyment, as happiness [which is heteronomous] does, but indicates a satisfaction in one's existence, an analogue of the happiness which must necessarily accompany the consciousness of virtue? Yes! this word is self-contentment, which in its proper signification always designates only a negative satisfaction in one's existence, in which one is conscious of needing nothing. Freedom and the consciousness of it as a faculty of following the moral law with unyielding resolution is independence on inclinations, at least as motives determining (though not as affecting) our desire, and so far as I am conscious of this freedom in following my moral maxims, it is the only source of an unaltered contentment which is necessarily connected with it and rests on no special feeling. This may be called intellectual contentment. (Kant, 1788/Reference Kant and Abbott1889, p. 148)

Here Kant stresses that in following the moral law one reaches a special form of self-contentment. It is a kind of satisfaction that is both negative and positive. It is negative because it is a “satisfaction in one's existence, in which one is conscious of needing nothing” — not depending on anything external; it is positive because it is “an analogue of the happiness which must necessarily accompany the consciousness of virtue.”

Kant clarifies the negative sense of the self-contentment by contrasting it with “the sensible contentment” (Kant, 1788/Reference Kant and Abbott1889, p. 148). First, unlike this negative satisfaction in which “one is conscious of needing nothing,” “the sensible contentment” will eventually leave us unsatisfied, because it “rests on the satisfaction of the inclinations. … For the inclinations change, they grow with the indulgence shown them, and always leave behind a still greater void than we had thought to fill” (Kant, 1788/Reference Kant and Abbott1889, p. 148). Second, unlike this negative satisfaction, the satisfaction of inclinations is either self-love (selfishness) or self-conceit (self-satisfaction) — both oppose the moral law and must be checked by it (see Kant, 1788/Reference Kant and Abbott1889, p. 120). Third, the origins of these two kinds of satisfaction are different: one from inclinations being satisfied and the other from respecting the moral law — actions are done from duty, not just in accordance with duty, as a result of pleasant feelings (see Kant, 1788/Reference Kant and Abbott1889, p. 147). Finally, these two kinds of satisfaction do not stand on the same level; the satisfaction of respecting the moral law is more foundational. Kant states in sympathy with Epicurus that

indeed the upright man cannot be happy if he is not first conscious of his uprightness; since with such a character the reproach that his habit of thought would oblige him to make against himself in case of transgression, and his moral self-condemnation would rob him of all enjoyment of the pleasantness which his condition might otherwise contain. (Kant, 1788/Reference Kant and Abbott1889, p. 147)

However, he immediately adds that, for him, in order for such an uprightness to be possible, “[t]he moral disposition of mind” must be “combined with a consciousness that the will is determined directly by the [moral] law” (Kant, 1788/Reference Kant and Abbott1889, p. 147).

Kant clarifies the notion that intellectual contentment is independent of inclinations by going on to say that this contentment does not lie in an intellectual vacuum completely detached from inclinations and wants. Rather, it is simply “free from their influence”:

Freedom itself becomes in this way (namely indirectly) capable of an enjoyment which cannot be called happiness, because it does not depend on the positive concurrence of a feeling, nor is it, strictly speaking, bliss, since it does not include complete independence on inclinations and wants, but it resembles bliss in so far as the determination of one's will at least can hold itself free from their influence. (Kant, 1788/Reference Kant and Abbott1889, p. 148)

On the other hand, Kant elaborates on the positive sense of self-contentment later in The metaphysics of morals by stating that it is “a moral pleasure that goes beyond mere contentment with oneself (which can be merely negative) and which is celebrated in the saying that, through consciousness of this pleasure, virtue is its own reward” (Kant, 1797/Reference Kant and Gregor1996, 6:391). It is “feel[ing] happy in the mere consciousness of [one's] rectitude” (Kant, 1797/1996, 6:388). This feeling is not a sensible feeling, but a moral one, “a feeling of the effect that the lawgiving will within the human being exercises on his capacity to act in accordance with his will” (Kant, 1797/Reference Kant and Gregor1996, 6:387). It can also be called ‘moral happiness’ (though Kant dislikes the term) “which consists in satisfaction with one's person and one's own moral conduct, and so with what one does” (Kant, 1797/Reference Kant and Gregor1996, 6:388).

Confucius’ peace-pleasure — despite its grounding on human-heartedness and the Way, rather than on what Kant calls the “moral law” — shares precisely these characteristics of Kant's intellectual or self-contentment. (a) Confucius’ peace-pleasure is a satisfaction in one's existence. It is a satisfaction based on practicing human-heartedness and following the Way, without which no authentic satisfaction or contentment is possible. It is also self-rewarding and self-fulfilling. (b) It is free from the influence of material conditions, inclinations, and wants (6:11, 7:16). It does not depend on the positive concurrence of an empirical feeling, but it is still a kind of peace-pleasure in the midst of different feelings. A Confucian exemplary person may be in a period of mourning but still be at peace with himself, that is, free from moral guilt (17:21).Footnote 25 Being “free from [inclinations’] influence,” however, for both Confucius and Kant, does not mean destroying or wiping out all inclinations. Rather, it means that inclinations must be checked, regulated, and ruled by ethical concerns.

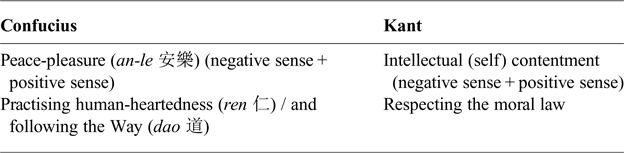

Now the comparison between Confucius’ peace-pleasure and Kant's intellectual contentment can be summarized as follows:

It is worth noting, however, that compared with Kant's more realistic view of inclinations in their influence on our ethical lives, Confucius’ view is more optimistic. While Kant stresses reason's constant fight against inclinations and feelings (Kant, 1797/Reference Kant and Gregor1996, 6:408), Confucius emphasizes that we work with inclinations and feelings, through cultivation (xi, learning-practising, 1:1, 1:4, 17:2; xiu, cultivation, 7:3, 12:21, 14:42; and ke, overcoming inclinations, 12:1), and that one's inclinations and feelings can be tamed.Footnote 26 For Confucius, the process of cultivation does not have to always be a fierce battle between morality and inclinations; rather, it is like the working of bone, ivory, or jade. Sometimes heavy-handed cutting and carving are required, and other times mild and gentle polishing or grinding are (1:15). It is even possible for Confucius that practising human-heartedness and following the Way eventually becomes spontaneous and habitual (2:4). But, for Kant, “if the practice of virtue were to become a habit the subject would suffer loss to that freedom in adopting his maxims which distinguishes an action done from duty” (Kant, 1797/Reference Kant and Gregor1996, 6:409); that is, if the practice of virtue becomes a habit and makes no choices between acting from one's maxims and acting from duty, then it should no longer be regarded as a practice of virtue.

Moreover, with regard to Confucius’ human-heartedness and the Way and its counterpart in Kant, the moral law, there lies an important difference. While both Confucius’ human-heartedness and the Way on the one hand and Kant's moral law on the other speak of the idea of duty, what Kant stresses is our respect for the moral law as well as our falling short in completely acting out of respect for it. Kant worries more about those who with a good heart (compassion) may still act against the moral law; he is less worried about those who act out of the moral law even though without a proper disposition (see Kant, 1785/Reference Kant, Gregor and Timmermann2011, 4:398). Confucius, in contrast, tends to believe or assume (perhaps too optimistically) that those with a good heart would normally do the right thing, and that at least without a good heart, the reluctant following of bitter duty does not mean much ethically speaking.

Furthermore, Kant says, “It [virtue] is always in progress because, considered objectively, it is an ideal and unattainable, while yet constant approximation to it is a duty” (Kant, 1797/Reference Kant and Gregor1996, 6:409). In contrast, what Confucius focuses on is trusting our ability to actually act from human-heartedness and to follow the Way. In other words, for Kant, there is always a vertical (qualitative) gap between a moral agent and the moral law, and, for Confucius, there is no vertical gap between the practice of a moral agent on the one hand and human-heartedness and the Way on the other hand (7:30) — there is only a temporal, a horizontal, quantitative distance to cover; that is, one must constantly practise human-heartedness and follow the Way till the end of his or her life (4:5, 8:7).

Finally, another difference between Confucius’ peace-pleasure and Kant's intellectual contentment is that, while Confucius’ peace-pleasure implies and includes a “liking” disposition, an emotional engagement, Kant separated such a disposition from his idea of intellectual contentment, and takes it to be a disposition (rather than part of pure practical reason) for which we can only strive:

[I]t is not within the power of any human being to love someone merely on command. It is, therefore, only practical love that is understood in that kernel of all laws. To love God means, in this sense, to do what He commands gladly; to love one's neighbor means to practice all duties toward him gladly. But the command that makes this a rule cannot command us to have this disposition in dutiful actions but only to strive for it. For, a command that one should do something gladly is in itself contradictory because if we already know of ourselves what it is incumbent upon us to do and, moreover, were conscious of liking to do it, a command about it would be quite unnecessary; and if we did it without liking to do it but only from respect for the law, a command that makes this respect the incentive of our maxim would direct counteract the disposition commanded. (Kant, 1788/Reference Kant and Gregor1996, 5:83)

Kant makes several points in this passage. First, love from inclinations or dispositions, or what Kant calls “pathological love” (Kant, 1788/Reference Kant and Gregor1996, 5:83; Kant 1785/Reference Kant, Gregor and Timmermann2011, 4:399) cannot be on command. One cannot be commanded to love another, just as one cannot be commanded to have a genuine smile. Second, to love God or to love one's neighbour, as practical (moral) love, is respectively to do what God commands and to practise all duties toward him — gladly. Third, however, this glad disposition should not be taken as readily there in us, for otherwise there would be no need for a command. If I am already gladly practising all duties toward my neighbour, then there is no need to command me to do so.Footnote 27 Nor should this glad disposition be seen as practically or morally irrelevant, such that — as long as I rationally do my duty — I do not need to care about my disposition of liking to do my duty — even when my disposition would go against the command. For example, consider a scenario where one has the disposition of dislike even though one is rationally following the moral command by visiting one's hospitalized friend, reluctantly and begrudgingly. Fourth, rather, one should do one's duty but also “strive” (perhaps involving overcoming or cultivating one's desires and inclinations, but presumably having nothing to do with pretending or faking) for a disposition of liking to do it, in an “uninterrupted but endless process” after “the archetype” of “thoroughly liking to fulfill all moral laws” (Kant, 1788/Reference Kant and Gregor1996, 5:83).Footnote 28

Kant later calls this kind of “liking” “the subjective ground of actions” that is an “indispensable complement to the imperfection of human nature,” and he argues that without it the command of duty “is not very much to be counted on” because “what one does not do with liking he does in … a niggardly fashion — also probably with sophistical evasions from the command of duty” (Kant, 1794/Reference Kant, Wood and Giovanni1998, 8:338).

Here Kant talks about not only “the representation of the duty” (knowing what one ought to do), “following duty” (the execution of duty, willingness to do it), but also about the subjective ground (“liking”) in following duty (gladly doing it) (Kant, 1794/Reference Kant, Wood and Giovanni1998, 8:338). These seem to correspond to Confucius’ discussion of knowing what is human-heartedness and the Way, willing to practise them, and taking pleasure (liking) in doing them — which is not just an intellectual contentment, but also a dispositional liking.

However, there is also a significant difference between Kant and Confucius here. For Confucius, in the genuine (ideal or optimal) practising of human-heartedness and the following of the Way, the three threads of “knowing,” “willing,” and “having pleasure” can be optimistically and actually braided into a unified cord (6:11 and 7:15). By contrast, Kant, both in his discourse about following duty and in his realistic judgement of human conditions, stresses the actual separation of the three threads of “representing,” “willing,” and “liking” with regard to the moral law. He takes the “liking” disposition as only an archetype one should strive for, a perfection not completely realizable for us in this life.Footnote 29

VI. Confucius’ le 樂 (pleasure and moral pleasure) versus Aristotle's pleasure and eudaimonia

As noted above, Confucius uses the word le in multiple ways, a major one of which being ‘pleasure’ (in modern Chinese, kuai-le 快樂), and his signature one being moral pleasure. We shall see below that in using the word le to mean ‘pleasure,’ Confucius’ view resembles Aristotle's view of pleasure, albeit with substantial differences. We shall also see that in using the word le to mean Confucius’ moral pleasure, there is no counterpart for Aristotle. Moreover, Aristotle's idea of eudaimonia Footnote 30 is usually translated as ‘happiness’ in English, which in turn is translated as xing-fu 幸福 in Chinese (unwittingly treated as an equivalent to ‘satisfaction,’ man-yi 滿 意), which again is often inappropriately and without qualification taken to be a translation of Confucius’ moral pleasure (le) or peace-pleasure (an-le).Footnote 31 Thus, we see a series of rough equivalents in the literature: eudaimonia ⇄ happiness ⇄ xing-fu 幸福 (⇄satisfaction, man-yi 滿意) ⇄ le 樂. These equivalences are careless and probably misleading; in any case, they do not prove that eudaimonia is the same as or similar to Confucius’ le.

While Confucius and Aristotle are both interested in examining the experiences of pleasure or pleasant feelings, Confucius only lays out instances of le (pleasure, or moral pleasure) in particular life occasions (1:1, 3:20, 11:13, 14:13, 13:15, 16:5, 17:21), whereas Aristotle clearly attempts a general theory of pleasure. Aristotle not only tries to describe general features of pleasure (Aristotle, n.d./Reference Broadie and Rowe2002, 1175b, 1174b, 1173b), to classify kinds of pleasure (Aristotle, n.d./Reference Broadie and Rowe2002, 1173b-1174a, 1175a-1176a), to rank them in a hierarchy (Aristotle, n.d./Reference Broadie and Rowe2002, 1176a), but also tries to provide a general definition of pleasure: whatever completes and blesses a human being is pleasure in its primary sense (Aristotle, n.d./Reference Broadie and Rowe2002, 1176a).

The differences between Confucius’ moral pleasure and Aristotle's eudaimonia can be shown in two ways. First, the highest form of eudaimonia, according to Aristotle, is contemplation (Aristotle, n.d./Reference Broadie and Rowe2002, 1177a12ff, 1177b30ff), which is completely absent, as well as alien, to Confucius. Confucius is very sceptical about what any speculation outside the context of concrete learning and practical everyday life can accomplish: “The Master said, ‘I once engaged in thought for an entire day without eating and an entire night without sleeping, but it did no good. It would have been better for me to have spent that time in learning’” (15:31). Moreover, the idea of zhi 知 (to know, to be wise) in the Analects has to do with knowing right and wrong, what is appropriate or not, in concrete situations, but has nothing to do with theoretical thinking. For Confucius, “to think” and “to know” are practical or pragmatic. In general, according to LI Zehou's widely accepted view, the ancient Chinese tradition subscribes to practical or pragmatic reason (shi yong li xing 實用理性) rather than to pure, theoretical reason (chun cui ling xing 純粹理性 or li lun li xing 理論理性). The subjects of Aristotle's contemplation are divinity, God, and immortality. The subjects of Confucius’ thinking and knowing, by contrast, are rituals, virtues, human-heartedness, the Way, and how to achieve peace-pleasure. Aristotle's contemplation is thinking for its own sake; Confucius’ thinking (si) and knowing (zhi) are always situated in a practical human context. For Aristotle, the divine character in human beings, the best possible way of being human, is their capacity for contemplation. For Confucius, by contrast, the best way to be human is to practise human-heartedness and to follow the Way.

Second, Confucius’ moral pleasure does not rely on, throughout an entire life, enjoying external goods, such as good birth, friends, children, wealth, looks, health, strength, as Aristotle's eudaimonia does (Aristotle, n.d./Reference Broadie and Rowe2002, 1099a32-1099b7, 1101a14-16, 1100a8-9). In other words, one can have Confucius’ moral pleasure even in a simple material life and even without, as Confucius puts it, having brothers. This pleasure is a state of being that focuses on inner harmony, grounded on human-heartedness and the Way, and its nature stays the same whether one lives a long life (as did Confucius himself, see 7:19) or not (as was the case with YAN Hui, see 6:3, 11:7). Practising human-heartedness and following the Way is sufficient to make one worthy of this moral pleasure. But, for Aristotle, one who lives a short life cannot be considered to have achieved eudaimonia — in the sense of “living well,” as opposed to “acting well” (see YU, Reference YU2007, pp. 172-176). In short, Confucius’ moral pleasure focuses on the positive state of a moral agent from the subjective side, from “within” (see 1:14, 15:32), that is, deontological (also see LEE, Reference LEE, Angle and Slote2013, pp. 47–55). However, Aristotle's eudaimonia incorporates both virtues and external luck. Even when Aristotle talks about virtues, he never addresses them in the first person, i.e., from the subjective perspective. Thus there seems nothing in his eudaimonia that is like Confucius’ moral pleasure or Kant's “intellectual contentment.” While I do not deny that there are a number of widely accepted affinities between Aristotle's ethics and Confucius’ — for example, on practical wisdom and appropriateness (yi 義), on the mean or the middle way, and on virtue or de 德 — nonetheless, Confucius’ moral pleasure and Aristotle's conceptions of pleasure and of eudaimonia are quite different.

In a recent book, Philip Ivanhoe interprets Confucius as holding a conception of happiness that is “akin to eudaimonia's sense of being favored by the gods” (Ivanhoe, Reference Ivanhoe2017, p. 131). But this interpretation is problematic in several ways. First, it is baseless for Ivanhoe to attribute the word “happiness” (understood in Chinese as xing-fu 幸福, given the equivalences mentioned above) to Confucius. Second, it confuses rather than clarifies Confucius’ views on moral pleasure to use “happiness” (xing-fu 幸福) and “joy” (le 樂) interchangeably, as Ivanhoe does: “for Kongzi [Confucius] happiness or joy is the feeling that one is living well. … This experience and sensation is the core of Confucian happiness or joy” (Ivanhoe, Reference Ivanhoe2017, p. 136). Moreover, Ivanhoe's interchangeable use of “happiness” (xing-fu) and “joy” (le) seems to be at direct odds with his own distinction between what he calls “a fully happy life”Footnote 32 and “true happiness”Footnote 33 for Confucius where only the latter is treated as equivalent to joy (le). Thus, readers may wonder if they should understand Ivanhoe as treating “happiness” (xing-fu) and “joy” (le) as equivalents or understand him as treating them to be different.

According to Ivanhoe, Confucius holds both that “the ethical life of following the Dao is the only source of true joy [presumably, “true happiness” too as Ivanhoe uses “joy” and “true happiness” interchangeably]. …” (Ivanhoe, Reference Ivanhoe2017, p. 133, fn. 12, my emphasis and addition) and that in order to live a happy life it is not enough to just follow the dao: “Following the Dao is the necessary condition for enjoying these other goods, and to a certain extent, though not completely, it is sufficient for a happy life” (Ivanhoe, Reference Ivanhoe2017, p. 132, my emphasis). What could it mean to say ‘A is sufficient for B, but not completely’? If A is not completely sufficient for B, then it is not sufficient for B. Wittingly or unwittingly, Ivanhoe has blended two understandings of “a happy life”: one life — like YAN Hui's and Confucius’ — is joyful and self-sufficient in following the dao and in practising human-heartedness (regardless of whether they obtain other goods in life, and Confucius is certainly not against obtaining these goods), and the other life in which one not only follows the dao but also luckily and deservingly (though the idea of desert seems under development in Confucius’ Analects) obtains other goods — a life that Aristotle would embrace. Thus, by misreading Aristotle's happy life into Confucius’ joy (le 樂, I prefer to translate it as moral pleasure) of following the dao, Ivanhoe has missed the important point in Confucius’ view that external goods are not part of the self-sufficient idea of moral pleasure itself (also see Olberding, Reference Olberding2013, p. 429). Confucius’ disciple YAN Hui's life was not fortunate as a life, but neither Confucius nor Confucians ever denied the value of YAN Hui's pleasure in practising human-heartedness and following the Way. For Confucius, ‘living well’ means exactly (no more and no less) ‘acting well’ all throughout one's life (4:5, 8:7); for Aristotle, ‘living well’ is more than ‘acting well,’ since the former depends on luck whereas the latter does not. In terms of this sense of pleasure, Confucius is a Kantian, not an Aristotelian. Admittedly, Confucius did believe that practising human-heartedness and following the Way may (very likely) have objective effects. If you respect others, then all are likely to be your brothers (12:5), and exemplary persons’ moral practice can naturally have influence on others as the wind can bend the grass (12:19). But, for Confucius, such objective effects do not form a necessary part of or necessary condition for moral pleasure. He did not argue for a separate notion of ‘a happy life’ (as Ivanhoe has attributed to him) construed as a combination of the feeling of joy and the attainment of other external goods, i.e., ‘a happy life’ seen from an objective perspective. Therefore, this so-called conception of ‘a happy life’ is wrongly attributed to Confucius.

VII. Conclusion

Confucius’ peace-pleasure indicates an ethically optimal state of being that one can reach only by acting from human-heartedness and by walking on the Way, even though in reality no one seems to constantly and for a whole life acts thus (6:7). Acting from human-heartedness and walking on the Way does not mean one must sacrifice the maximum one has — either in terms of material goods or of one's very life — on all occasions (15:9, 15:35). Nor does it imply a highly ascetic moral life (4:5, 8:13). It is not contingent upon external conditions, and it is a state of authentic living that fulfills the very purpose of authentic human life. This state differs from Aristotle's eudaimonia because it does not include or depend upon external conditions. In this regard, Confucius’ peace-pleasure purports to be completely autonomous and remarkably similar to Kant's idea of “intellectual contentment,” that is, the state arrived at when one respects the moral law and acts out of duty.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments, suggestions and criticisms, and to Jill Flohil and Arthur Ling for their generous editorial help. I also want to thank Kwantlen Polytechnic University for offering me one course release toward the writing of this article, and to thank LU Yinghua and Patrick Moran for their helpful suggestions and comments on earlier versions of this article. Last but not least my thanks go to Michael Hunter for tuning the English of the article and for preparing the Abstract in French.