In 1762 Leopold Mozart made two trips with his family to show off the rapidly developing musical skills of his children, Maria Anna (Nannerl) and Wolfgang. The family first travelled to Munich, probably in January, where they stayed for three weeks. According to Maria Anna's reminiscence of 1792 (our sole source), the children played for the Bavarian Elector, Maximilian III Joseph, but otherwise nothing is known of this trip.Footnote 1 On 18 September that same year (according to Maria Anna), the family left Salzburg for Vienna, where they were to remain for almost three months. Wolfgang was now six and Nannerl eleven. On the way, the Mozarts stopped for several days in Passau, where Wolfgang (but not Nannerl) played for Prince-Bishop Joseph Maria von Thun und Hohenstein, receiving from him a gift of ‘one whole ducat’, as Leopold sarcastically wrote to Lorenz Hagenauer, his friend and Salzburg landlord.Footnote 2 From Passau they then travelled down the Danube by boat to Linz, where they stayed from 26 September to 4 October, and the children gave what was apparently their first public concert. According to Leopold's letter to Hagenauer of 16 October, the Mozarts left Linz on 4 October, and continued downstream by what he called the ‘Wasser=ordinaire’ (more commonly referred to at the time as the ‘Ordinari Schiff’), reaching Mauthausen that evening.Footnote 3 Following a short midday stop in Ybbs an der Donau on 5 October – where Wolfgang astonished the Franciscan fathers with his organ playing – and an overnight stay in Stein an der Donau, the Mozarts landed in Vienna on 6 October at around 3 p. m.

Everything we know about the Mozarts’ journey to Vienna in 1762, their arrival and their lodgings in the city derives solely from Leopold's first three letters to Hagenauer, on 3 October 1762 (sent from Linz), and 16 and 19 October 1762 (sent from Vienna). Just one of these letters, that of 16 October, is known to survive in Leopold's hand; the other two are known only from early copies.Footnote 4 Our focus here will be on the two letters from Vienna, on 16 and 19 October. Both were first published in Nissen's biography of Mozart in 1828 – but the letter of 16 October is given by Nissen in heavily edited form that omits key information, and the portion of Leopold's letter of 19 October that refers to their Viennese lodgings is omitted entirely.Footnote 5 The texts of both letters were first published in full by Ludwig Schiedermair, in his 1914 edition of Leopold's letters.Footnote 6

On 16 October Leopold writes:

Bey den anlanden war schon der Bediente des H: Gilowsky zugegen, der in das Schiff kam und mich dann in das quartier führte. wir eylten aber bald einem Wirthshause zu, um unsern hunger zu stillen; nachdem wir vorhero unsere Bagage in dem quartier in sicherheit und Ordnung gebracht. Dahin kam dann auch H: Gilowsky uns zu empfangen. [. . .]

Eins muß ich sonderheitl: anmerken, daß wir bey der schantzlmauth ganz geschwind sind abgefertigt und von der Hauptmauth gänzlich dispensirt worden. daran war auch unser H: Woferl schuld: dann er machte alsogleich seine Vertraulichkeit mit dem H: Mautner, zeigte ihm das Clavier, machte seine Einladung, spielte ihm auf dem geigerl ein Menuet, und hiemit waren wir expediert. der Mautner bath sich mit der grösten Höflichkeit die Erlaubniß aus uns besuchen zu därffen, und notirte sich zu diesem Ende unser quartier.Footnote 7

The servant of Herr Gilowsky was already present when we landed; he came onto the ship and then led me to our quarters. But we soon hurried to an inn to quiet our hunger, after first bringing our baggage to safety and good order in our quarters. Herr Gilowsky also came there to greet us.

I must make special note of one thing: we were dispatched very quickly through the Schanzlmaut and were entirely exempted from the Hauptmaut. For this we are indebted to Herr Woferl, who immediately became an intimate acquaintance of Herr Customs Officer, showed him the clavier, invited him to visit, and played him a minuet on his little violin, and thus we were expedited. The customs officer, with utmost politeness, requested permission to visit us, and to this end noted down our address.Footnote 8

The ‘Schanzl’ was a strip of land between what is now called the Danube Canal and the old city wall; boats like the one carrying the Mozarts landed at the Schanzl and passengers disembarked.Footnote 9 The Schanzl had its own customs house (the Schanzlmaut), where arrivals were processed before entering the city through the Schanzl Gate (Schanzl-Tor). As Leopold implies, arrivals would often continue on to further processing at the main customs (Hauptmaut), just inside the city wall.

Leopold writes that the servant of Herr Gilowsky met them at the boat, and that Gilowsky himself came to visit them in their quarters. This is the first reference in the Mozart family correspondence to a name that subsequently appears often in their letters, that of the Salzburg Gilowskys, who became their intimate friends.Footnote 10 In 1762 only three male members of the Gilowsky family were old enough to have been the person Leopold is referring to here. Franz Anton Gilowsky (1708–1770) held a succession of positions at the Salzburg court, including steward and court surgeon, and his social standing was thus roughly the same as Leopold's. In 1754 Franz Anton had purchased a house in the Getreidegasse, just a few doors down from the Mozarts, so the two could easily have met by 1762. Leopold writes as if Hagenauer will know who he means, and Hagenauer would probably also have known the Gilowskys in Getreidegasse. Alternatively, Leopold might have been referring to Franz Anton's son from his first marriage, Johann Joseph Anton Ernst (1739–1789); a third possibility is Franz Anton's younger brother Wenzel Andreas (1716–1799), the father of Franz Xaver and Maria Anna Katharina (‘Katherl’) Gilowsky, who later became close friends of Wolfgang and Nannerl. To our knowledge, there were no other Gilowskys to whom Leopold could have been referring at that time, and no evidence that any other Gilowsky was living in Vienna in 1762. Thus it must have been one of these three men – Franz Anton, Johann Joseph Anton Ernst, or Wenzel Andreas – who was in Vienna when the Mozarts arrived; at present we cannot say which.Footnote 11

The customs official in Leopold's anecdote can be identified with reasonable certainty.Footnote 12 The Schanzlmaut had a small staff of its own that was listed in government directories. The directory for 1760 gives the staff as:

The ‘Einnehmer’ (collector) was the head of the Schanzl customs station. It was a resident post, and Maximilian Graf, the Einnehmer in 1760, lived in house No. 1329, just outside the city wall (see Figure 1); the customs station itself was No. 1330. The staff of the Schanzlmaut was supplemented by ‘Beschauer’ (inspectors) from the Roßau customs station.

Figure 1 Joseph Daniel von Huber, ‘Scenographie oder Geometrisch Perspect. Abbildung der Kayl: Königl: Haubt: u: Residenz Stadt Wien in Oesterreich’ (1778), the so-called ‘Vogelschauplan’, detail, showing the Schanzl, the Schanzlmaut (no. 1330), the residence of the Einnehmer (no. 1329), and the Schanzl-Tor. Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Sammlung Woldan. Used by permission

The directory for 1765 (the next volume currently available online) shows changes in the staff of the Schanzlmaut:

Maximilian Graf, the former Einnehmer, had died on 9 June 1762 of tuberculosis (‘lunglsucht’).Footnote 15 On 15 August Johann Lampl (Lampel, Lämpl) married Graf's widow Maria Anna.Footnote 16 That she remarried a little over two months after her husband's death may seem like unseemly haste, but the marriage had obvious immediate advantages for both: Maria Anna would be able to remain in her home at the Schanzlmaut, and Johann Lampl, the new resident Einnehmer, would have a wife to take care of it. Thus Johann Lampl was certainly the Einnehmer at the Schanzlmaut when the Mozarts arrived on 6 October, and he was very likely the official whom little Wolfgang charmed and who requested permission to visit.

It has not generally been noted in the Mozart literature that Leopold's letter of 16 October 1762 implies that the family's lodgings had been arranged before their arrival: Herr Gilowsky (whichever one it may have been) evidently knew they were coming, knew the expected date and time of their arrival well enough to send his servant to meet them, and had arranged a place for them to stay.Footnote 17 Because their lodgings were already arranged, the Mozarts were able to give their address to the Einnehmer at the Schanzlmaut so that he could visit. The family went directly to their lodgings to secure their luggage, and then immediately to an inn to have something to eat.

Until Leopold's letter to Hagenauer of 19 October was published in full by Schiedermair in 1914, there was no known primary evidence on the location of the family's lodgings in Vienna in 1762. In its issue of 27 January 1860 (Mozart's birthday) the Wiener Theaterzeitung published a short item entitled ‘Die Mozart-Häuser in Wien’. It begins:

B. Das erste Haus in Wien, welches Mozart's Fuß betrat, war das Einkehrwirthshaus ‘zum weißen Ochsen’ (heute ‘zur Stadt London’,) am alten Fleischmarkt, damals die Nummer 729 tragend, jetzt Nr. 684. Es geschah, als im Herbste des Jahres 1762 Mozart's Vater mit seiner Familie auf der ersten Kunstreise von München aus über Linz nach Wien ging.Footnote 18

B. The first house in Vienna in which Mozart set foot was the inn ‘Zum weißen Ochsen’ (today ‘Zur Stadt London’) on the old Fleischmarkt, at that time No. 729, now No. 684. It happened in the autumn of the year 1762, when Mozart's father and his family made their first artistic tour from Munich by way of Linz to Vienna.

(The writer incorrectly conflates the Mozarts’ trip to Munich in 1762 with their first trip to Vienna.) The notion that the Mozarts stayed at the inn ‘Zum weißen Ochsen’ was taken up in a fictionalized story by Moriz Bermann published in 1862, ‘Mozart und Erzherzogin Maria Antoinette als Brautleute’, where it is implied that the Mozarts stayed in the inn during their entire sojourn in Vienna. Bermann published a lightly adapted version of the same story in 1864 in the Illustrirte Jugend-Zeitung, a children's magazine.Footnote 19

Although the item in the Wiener Theaterzeitung in 1860 is not explicitly attributed, the initial ‘B’ may provide a clue to its author. Such initials appear sporadically in the Wiener Theaterzeitung at this time and probably refer to specific authors, but no key is given. Adolf Bäuerle, founding editor of the newspaper, might seem to be a candidate, but he had died in Basel on 20 September 1859. On 6 January 1860, three weeks before the appearance of the Mozart item, the Wiener Theaterzeitung published an article attributed to (presumably) the same ‘B’ that referred to a meeting of the Österreichisches Kunstverein on 29 December 1859.Footnote 20 So ‘B’ cannot have been Bäuerle. Bermann himself might be a possibility, but at present we have no evidence that he ever wrote for the Wiener Theaterzeitung. Whoever the author of the Mozart item may have been, this is the earliest known source for the claim that the Mozarts stayed at ‘Zum weißen Ochsen’ in 1762. It is possible that the claim was an invention.

This might easily have remained a forgotten curiosity of the nineteenth century, but the item was quoted (citing the Wiener Theaterzeitung) in the extensive categorical bibliography for the article on Mozart published in 1868 in Wurzbach's Biographisches Lexikon des Kaiserthums Oesterreich; Wurzbach then published the Mozart article as a separate book the following year, and this book long remained a standard reference.Footnote 21 At some point, the source in the Wiener Theaterzeitung came to be forgotten, and some scholars even suggested that the notion that the Mozarts stayed at ‘Zum weißen Ochsen’ might be an oral tradition, although there is no evidence for this.Footnote 22 Oddly enough, credit for the claim has also been given to Otto Jahn, even though ‘Zum weißen Ochsen’ is not mentioned in any edition of his biography of Mozart.Footnote 23 There was indeed an inn ‘Zum weißen Ochsen’ in the eighteenth century, at what (in 1771) became No. 729I (now Fleischmarkt 28 and Postgasse 15); but there is no evidence that the Mozarts ever stayed there.Footnote 24 Nevertheless, the notion became deeply embedded in the secondary and reference literature, and it is still often repeated today.

In his letter of 19 October 1762, Leopold informed Hagenauer where they were staying and gave a vivid description of their cramped quarters. This passage was not, however, published until 1914, when it appeared in Schiedermair's edition:

Vor allem aber wissen Sie, wo ich wohne? – Ich wohne in Fierberggaßl ohnweit der hochen Bruken im Tischler-Hause im ersten Stock. Das zim[m]er ist 1000 Schritt lang, und 1. Schritt breit. – Sie lachen? – uns ist es in der That nicht lächerlich[,] wenn wir einander auf die Hün[n]er Augen tretten. Noch weniger ist es lächerlich, wenn mich der Bub, und meine Frau das Mädl wo nicht über das armselige Beth herunterwerfen, doch auch uns wenigst alle Nacht ein paar Rippen eintretten. jedes unserer Bether hat meine 4 und ½ Spann: und dieser erstaunliche Pallast ist noch durch eine Wand in 2. Theile getheilt, in deren jeden eines dieser grossen Bether stehet, gedult! wir sind in Wien.Footnote 25

But above all, do you know where I am living? – I am living in Fierberggaßl not far from Hohe Brücke in the Tischler-Haus in the first floor.Footnote 26 The room is one thousand paces long and one pace wide. – You laugh? – For us it is in fact not amusing, when we step on each other's toes. It is even less amusing when the boy throws me every which way in the pathetic bed, or the girl does the same to my wife, and at least once every other night they also kick a couple of our ribs. Each of our beds is 4 and ½ of my spans wide; and this astonishing palace is divided into two parts by a wall, in each of which stands one of these big beds. Patience! We are in Vienna.

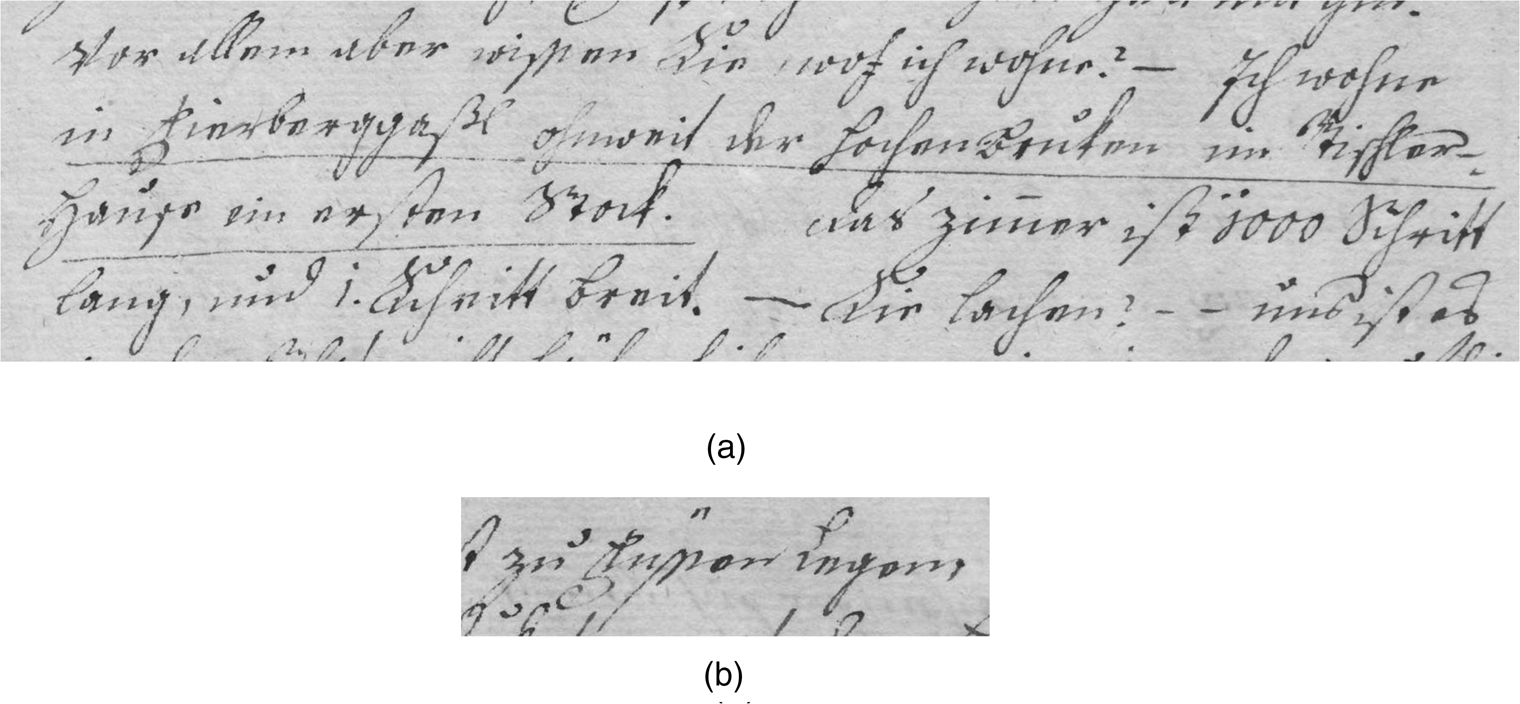

Schiedermair's transcription of this letter differs from the one given here in one tiny but crucial detail: Schiedermair gives the street name as ‘Hierberggaßl’, which is not a plausible match for any street name in Vienna at that time.Footnote 27 The corrected form ‘Fierberggaßl’ was first published in the new complete edition of the Mozart family correspondence in 1962. It is not difficult to see why Schiedermair might have mistaken the scribe's ‘F’ for an ‘H’; but comparison with the ‘F’ in ‘Füssen’ on the second page of the same letter shows unequivocally that the reading should be ‘Fierberggaßl’ (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Manuscript copy of Leopold Mozart's letter to Lorenz Hagenauer of 19 October 1762, in: ‘Abschrift von den Original=Briefen des Leopold Mozarts . . . ’, detail, pages 4 (‘Fierberggaßl’) and 2 (‘Füssen’). Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin – Preußischer Kulturbesitz. Used by permission

So far as we know, the first scholar to attempt to use this passage to pinpoint the location of the Mozarts’ lodgings in 1762 was Otto Erich Deutsch, in Mozart: Die Dokumente seines Lebens, published in 1961; this was the year before the publication of the corrected transcription, and Deutsch seems still to have relied on Schiedermair's edition. As a Vienna native, Deutsch would have found Schiedermair's ‘Hierberggaßl’ unintelligible, so he ignored it, focusing instead on Leopold's ‘Tischler-Haus’. ‘Tischler’ is an ordinary German word meaning ‘carpenter’ or ‘cabinetmaker’, and in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, several buildings in Vienna and its suburbs were referred to as ‘Tischler-Haus’ or ‘Tischlerisches Haus’ at one time or another. But none of these was in the vicinity of Hohe Brücke, so Deutsch (or perhaps his source, if he had one) hypothesized that Leopold's ‘Tischler’ was a corruption of the name ‘Ditscher’. At the time of the Mozarts’ visit in 1762, a hatmaker named Johann Heinrich Ditscher (also ‘Titscher’) owned the house that became No. 321I in Tiefer Graben, quite near Hohe Brücke (see Figure 3).Footnote 28 Deutsch guessed, then, that the Mozarts must have stayed in Ditscher's house (the site is today Tiefer Graben 16), but he stated this in Dokumente as if it were a fact:

Ob die Familie die erste Nacht oder die ersten Tage im Gasthof ‘Zum weißen Ochsen’ am Fleischmarkt verbracht hat, ist ungewiß. Jedenfalls wohnten sie Mitte Oktober am Tiefen Graben (jetzt Nr. 16) im Hause des Johannes Heinrich Ditscher.Footnote 29

Whether the family spent the first night or the first days in the inn ‘Zum weißen Ochsen’ on Fleischmarkt is uncertain. In any case, by mid-October they were staying in Tiefer Graben (now No. 16) in the house of Johann Heinrich Ditscher.

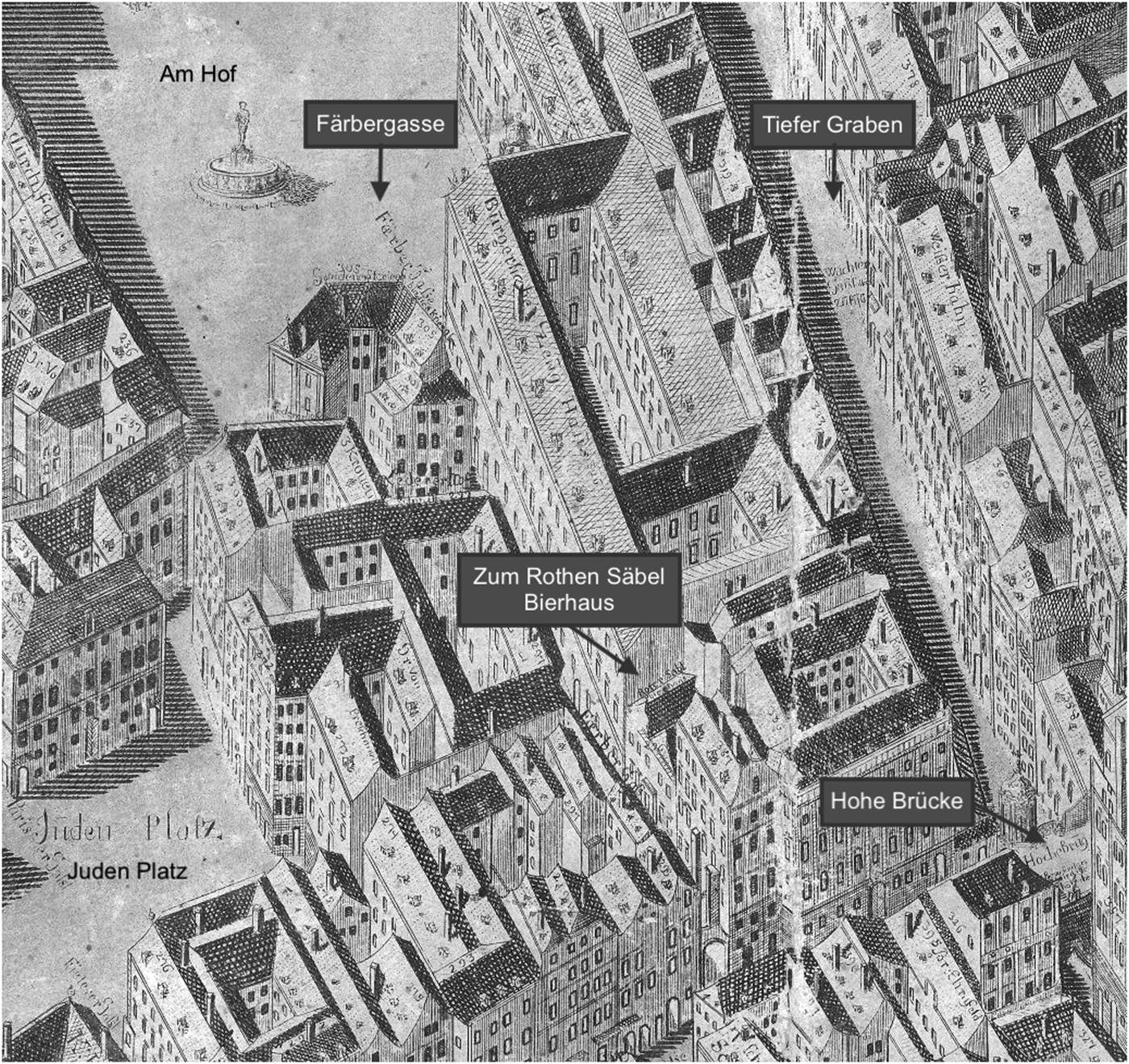

Figure 3 Joseph Anton Nagel, ‘Grund Riß Der Kaÿ. Königl. Residenz Stadt Wien . . . ’ (engraving, 1781), detail, showing the five houses discussed in this article: No. 296I, ‘Zum rothen Säbel’ (361II, 333III, today Färbergasse 3); No. 387I (382II, 352III, today Wipplingerstraße 19/Färbergasse 5); No. 321I (238II, 231III, today Tiefer Graben 16); No. 322I (237II, 230III, today Tiefer Graben 18); No. 323I (236II, 229III, today Tiefer Graben 20). On Viennese house numberings see note 24. Vienna, Stadt- und Landesarchiv. Used by permission

Deutsch's statement implies (although he does not say so) that Schiedermair's ‘Hierberggaßl’ was a corrupt (and quite implausible) rendering of ‘Tiefer Graben’. Nevertheless, Deutsch's ‘Ditscher’ thesis of 1961 came to be generally accepted for the next thirty years, and it was adopted in the second edition of Emily Anderson's translation of the Mozart family letters in 1966.Footnote 30 Although Deutsch was one of the editors of the 1962 publication of Mozart: Briefe und Aufzeichnungen, where Schiedermair's reading was corrected to ‘Fierberggaßl’, the commentary to Leopold's letter of 19 October in the new edition (the commentary was published in 1971) unaccountably retains Deutsch's implausible ‘Ditscher’ thesis, and continues to ignore the street name. No one seems to have noticed that Ditscher's house, No. 321I in Tiefer Graben, was relatively small and square (roughly 10 x 10 metres), and an unlikely match for Leopold's description of their long and narrow accommodation.Footnote 31

It is much more likely that ‘Fierberggaßl’ refers to Färbergasse, a short street parallel to Tiefer Graben, running between Am Hof and Wipplingerstraße. A house on Färbergasse is a better match for Leopold's description; it is the house that came to be numbered 296 (on the site of what is now Färbergasse 3; see Figure 3), which had a long and narrow wing extending back from the main house. Because it was just one street away and around the corner from Hohe Brücke, it can reasonably be said to be ‘not far’ from it, as Leopold writes.Footnote 32

At the time of the Mozarts’ visit, Färbergasse was more commonly referred to as ‘Färbergaßl’ (or some variant of that diminutive). It is also a relatively obscure street, not one that an out-of-town visitor such as Leopold would likely have heard of or read about – nor would there have been any reason for him to have seen the name of the street written down, once he was there. Thus his spelling in his letter to Hagenauer would have been a phonetic rendering of what Leopold thought he heard. In standard German ‘Färb’ is pronounced /fɛ:ɐb/, with the main vowel /ɛ/ diphthongized by the following ‘r’.Footnote 33 In the Bavarian dialect region (to which Viennese belongs), the tongue in this initial front vowel can tend to be placed higher than in standard German, moving the vowel in the direction of /ɪ/ (as in English ‘bit’) or even /i/ (as in English ‘beet’) and thus taking ‘Färb’ closer to /fɪ:ɐb/ or /fi:ɐb/. So it is plausible that Leopold thought he had heard ‘Fierberggaßl’ and thus spelled it that way. He would have had no reason to know that the street took its name from the dyers (Färber) who lived and worked there in the sixteenth century, and he would have had no reason to correct his spelling on that basis.Footnote 34

In the eighteenth century, house No. 296I in Färbergasse was owned by a series of cutlers (Messerschmiede), and early in the century the house gained an appropriate ‘Schild’ name, ‘Zum rothen Säbel’ (At the Red Sabre; see Figure 4).Footnote 35 The house was nestled between what was at that time the Bürgerliches Zeughaus on Färbergasse (No. 306I) and house No. 387I on the corner of Fäbergasse and Wipplingerstraße (now the site of Wipplingerstraße 19/Färbergasse 5). The Mozarts stayed in No. 387I in 1768, and Wolfgang and Constanze also lived there for a time in 1782. When the Mozarts visited Vienna in 1762, ‘Zum rothen Säbel’ (No. 296I) was owned by Agnes Erhardt, the widow of Sebastian Erhardt, who had died on 23 March 1762; Sebastian, a ‘Langmesserschmied’ (long-knife smith), was in turn the son of cutler Anton Erhardt, the previous owner of the house.Footnote 36

Figure 4 Joseph Daniel von Huber, Vogelschau der Inneren Stadt, Vienna (1785), detail, showing the street name (‘Færbergasse’) and house No. 296I, with the inscription ‘Roter Sabl / Bierhaus’. (Spellings in the annotations have been standardized.) Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, Sammlung Woldan. Used by permission

There is considerable confusion in the Mozart literature over the name ‘Zum rothen Säbel’. It is almost universally said today that the house on the corner of Färbergasse and Wipplingerstraße – No. 387I in Mozart's day – was called ‘Zum rothen Säbel’.Footnote 37 In fact, it was never called this during Mozart's lifetime. This name was not applied to that house until well into the nineteenth century: the earliest instance we have found is an advertisement in the Wiener Zeitung on 22 February 1821 for a new wine tavern (Wein-Ausschank).Footnote 38 For some decades thereafter the name ‘Zum rothen Säbel’ was confusingly applied to both houses (by then, No. 296I on Färbergasse had become No. 333III, and No. 387I on the corner had become No. 352III).Footnote 39 The wine tavern in the house on the corner became celebrated in the nineteenth century, and came to be known as the ‘Sabelkeller’ (often with no umlaut), which was said (perhaps fancifully) to have a historical connection with the famous Bänkelsänger of the seventeenth century, ‘Lieber Augustin’. The house was demolished in 1898.

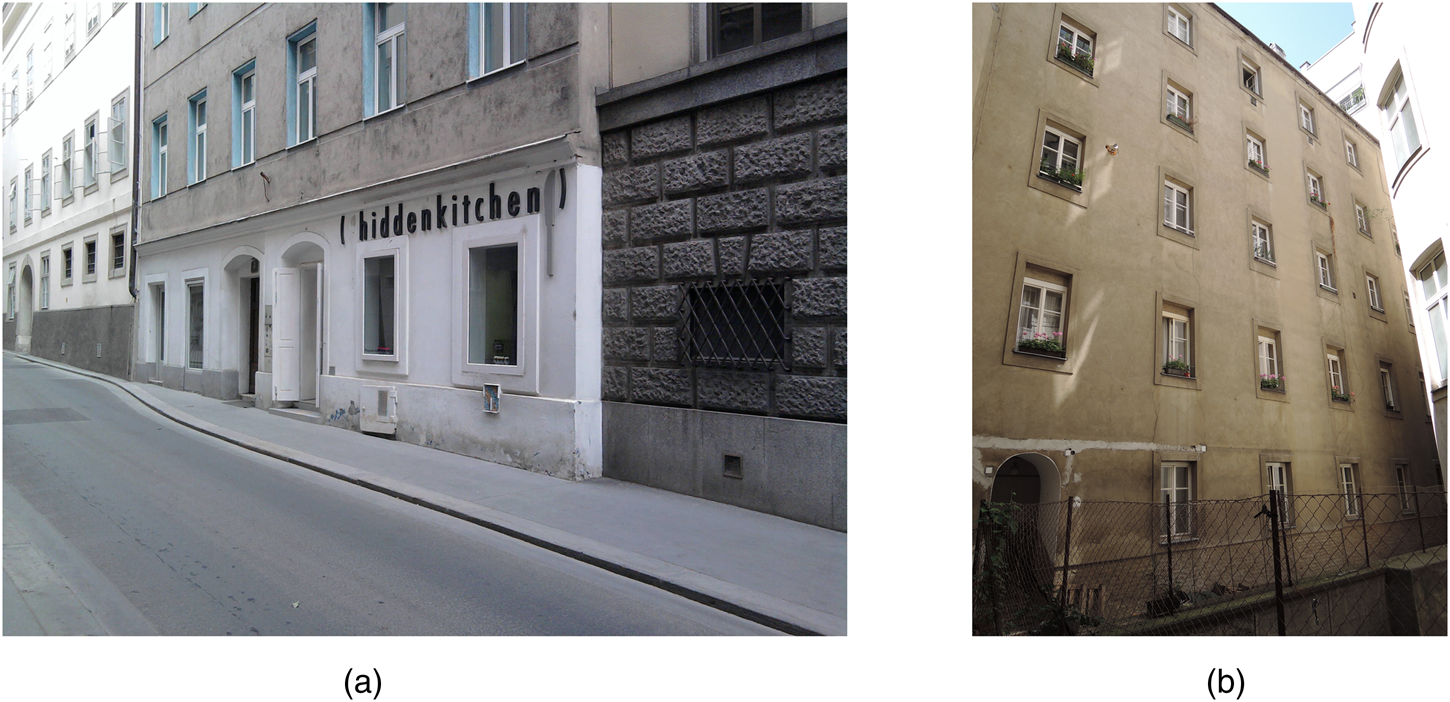

No floor plan survives for house No. 296I in Färbergasse as it was at the time of the Mozarts’ visit in 1762. However, a floor plan does survive for a new three-storey house built on the site in 1802 (Figure 5).Footnote 40 According to a long-standing stipulation on the owner, any modification to the house on this site was obliged to preserve the narrow gap between it and the rear of house No. 383II (386I); for that reason, the width of the extension in the new construction remained just as narrow as it had been in the previous house.Footnote 41 Indeed, even in its modern incarnation, the house on this site (Färbergasse 3) retains this long and narrow extension behind (Figure 6).

Figure 5 Floor plan of the new construction at No. 361II (296I) in Färbergasse, 1802, detail, showing the first floor, with the plan's Klafter scale superimposed. Vienna, Stadt- und Landesarchiv. Used by permission

Figure 6 Façade of Färbergasse 3 and an external view of the long and narrow extension behind. The width of the extension is the distance between the left edge of the façade and the main entry door on the left. (Photos: Michael Lorenz)

For convenience of comparison, in Figure 5 we have placed the scale beneath the plan of the first floor. The scale is in Klafter, a standard unit for measuring length in Vienna at that time, equal to 1.8965 metres; one Klafter consisted of 6 Viennese Fuß (each equal to 0.3161 m), as shown in the subdivisions at the left end of the scale.Footnote 42 The rooms in the extension are laid out in what is called, in the American South, ‘shotgun’ style, with a single line of rooms, one leading to the next; this is the only realistic choice for such a long and narrow structure. The two main rooms on the first floor of the extension are each just under 3 Klafter long (5.69 m = 18.67 ft) and around 2 Klafter 1 Fuß wide (4.11 m = 13.48 ft). The two rooms were connected via a single doorway; the combined length of the two rooms, including the width of the dividing walls, was nearly 7 Klafter (around 13 m, or roughly 42 ft), and this layout would certainly have made the space seem long and narrow. The layout also matches Leopold's description: ‘und dieser erstaunliche Pallast ist noch durch eine Wand in 2. Theile getheilt, in deren jeden eines dieser grossen Bether stehet’ (and this astonishing palace is divided by a wall into two parts, in each of which stands one of these big beds).Footnote 43 Leopold writes that each bed is 4 ½ of ‘his’ hand spans in width. In the eighteenth century, a ‘Spann’ was generally equivalent to two ‘Faust’ or two-thirds of a Fuß. In modern terms, a Spann was around 210 mm, so 4 ½ Spann were around 945 mm, or a bit less than one metre. A bed of that width, if pushed flush against the wall in one of the rooms on the first-floor of the extension, would have left just over 3 metres of floor space (just over 10 ft) between the bed and the opposite wall. This layout might well have seemed cramped for four people, with their luggage and a keyboard.

In describing their lodgings in Vienna in 1762, Leopold exaggerates the odd layout by writing: ‘das zimmer ist 1000 Schritt lang, und 1. Schritt breit’ (The room is one thousand paces long and one pace wide).Footnote 44 Wolfgang used a nearly identical phrase a little over twenty years later in his letter to Leopold of 22 January 1783, describing the apartment in which he and Constanze were living in the ‘Herbersteinisches Haus’ (No. 412I on Wipplingerstraße, not far from No. 296I and No. 387I): ‘Nun da habe ich ein zimmer – 1000 schritt lang und einen breit’ (Now I have a room there – one thousand paces long and one wide).Footnote 45 That house, while not having a long extension like No. 296I, did have an odd external shape and may have had oddly shaped rooms that prompted Wolfgang's description.

These two widely separated uses of the phrase by Leopold and Wolfgang have led some scholars to claim that it was – as the commentary to Leopold's letter of 19 October 1762 puts it – ‘eine scherzhaft übertreibende Redensart der Mozarts’ (a jocularly exaggerated saying of the Mozarts),Footnote 46 implying that it was used only within the family. But the phrase in fact has a source: a pedantically humorous anecdote published in the collection Ergötzlicher Aber Lehr= und Sittsamer auch von allerhand Unsauberkeiten und überlästigen Infamien rein bewahrter Burger=Lust (Delightful – but Edifying, Proper and Kept Free of Every Sort of Uncleanness and Incommodious Infamy – Diversion for Citizens), the title of an edition published in Augsburg in 1758. This collection, with slight variants of the same title, can be traced back to the mid-seventeenth century, and it was reissued many times in many editions. In the Augsburg edition of 1758, the anecdote reads:

Ein Edelmann war ein schändlicher Lügner und wann er gleich den größten Schnitzer brauchte, muste doch sein Diener solchen helffen bejahen, der es aber nicht länger thun wollte, mit Vermelden, daß sie alle beyde bey so handgreiflichen Unwahrheiten eine höchste Schand hätten. Der Edelmann entschuldiget sich, daß ers sich so angewöhnt hätte, und selber nicht merken könnte, der Diener soll ein andermahl, wann er, der Edelmann, wieder etwas zu erzehlen anfieng, daß ers abnehmen möchte, er würde es zu grob machen, solte er hinter ihm stehend ihn heimlich stossen, so wolle er in der Erzehlung schon behutsamer gehen. Was geschicht? Als bey einer Adelichen Zusammenkunft einer diß, der ander etwas anders, so er in frembden Landen gesehen, erzehlte, fieng dieser Lugen=Schmied an zu erzehlen, wie er in Welschland eine Kirche, tausend Schritte lang, gesehen, und in diesem stosset ihn der Diener, worüber er dermassen erschrickt, daß er in der Lugen nicht mehr weiß fortzukommen, sondern damit abbricht, sprechend: Ein Schritt breit: dessen die anderen alle anfiengen zu lachen, fürgebend, was das für eine Kirchen, tausend Schritte lang, und nur einen Schritt breit, seyn müsse? Entschuldiget er sich, sein Diener hätte ihn gestossen, sonst wollte er sie viereckigt gemacht haben.Footnote 47

A nobleman was an infamous liar, and whenever he was about to need the biggest fib, his servant had to agree to affirm it; but he did not want to do this any more, and announced that they both had very great shame from such palpable untruths. The nobleman apologized that he had become so in the habit of this that he could not notice it himself, so next time that he, the nobleman, again began to tell a story that the servant thought might become too outlandish, he should stand behind him and secretly poke him, so that he would proceed more carefully with the story. What happened? When at a gathering of aristocrats, one told of what he had seen in foreign lands and another told of something else he had seen there, this lie-smith began to tell how in Italy he had seen a church a thousand paces long. And at this point the servant poked him, which frightened him so much that he did not know how to proceed with the lie, but instead broke off, saying: One pace wide. At which all the others began to laugh, asking: what sort of church must it be that is a thousand paces long and one pace wide? He apologized, saying that his servant had poked him, otherwise he would have made it square.

This anecdote appeared in an edition of the collection as early as 1657, and it is present in every edition we have seen, differing only in spellings and inconsequential details.Footnote 48 Although this book is not known to have been in Leopold's personal library, his use of the phrase strongly suggests that he knew the book (or at least knew the phrase as a proverbial expression) and that he probably expected Hagenauer to recognize the reference.Footnote 49 But Leopold goes on to write to Hagenauer that this time it is no joke. Their quarters are so narrow that they are stepping on each other's toes, because (he implies) the beds take up much of the width of the rooms. They have to sleep two to a bed, Wolfgang with Leopold, and Nannerl with her mother; the beds, while too wide for the space, are too narrow for two, and Wolfgang is kicking him in the ribs and tossing him all over the bed. The rooms in the first floor of the extension of house No. 296I match well with this description.

Houses on this site in Färbergasse were associated with at least two other notable people. Just seven months after the Mozarts left Vienna, Dorothea Sardi (baptized 1 August 1763) was born in the house that would soon be numbered 296.Footnote 50 She went on to become a member of the Italian opera company of the Viennese court theatre; under her married name, Dorothea Bussani, she created the roles of Cherubino in the first production of Mozart's Le nozze di Figaro in 1786 and Despina in the first production of his Così fan tutte in 1790. The prominent psychiatrist and writer Baron Ernst von Feuchtersleben was born in the new house on this site on 29 April 1806.Footnote 51

In 1991 Walther Brauneis published a new hypothesis on the location of the Mozarts’ lodgings in 1762.Footnote 52 Brauneis took Leopold's ‘Tischler-Haus’ to refer not to Ditscher, as Deutsch had claimed, but rather to coppersmith Gottlieb Friedrich Fischer, who owned two houses on Tiefer Graben: No. 322I (today Tiefer Graben 18), adjacent to Ditscher's house, and No. 323I (today Tiefer Graben 20). Brauneis simply states as fact that the Mozarts stayed in No. 323I in 1762, writing: ‘Die bisherige Identifizierung des Mozart-Quartiers mit Nr. 16 (Eigentümer: Johann Heinrich Ditscher) ist nicht weiter aufrechtzuerhalten’ (The previous identification of the Mozarts’ quarters with No. 16 (owner: Johann Heinrich Ditscher) cannot be sustained). He offers no real evidence or explanation, but his reasoning seems to have been that the Mozarts had known at least one member of the Fischer family since at least 1768, and Leopold and Wolfgang stayed in one of Fischer's houses in 1773; ergo the Mozarts must have known him and stayed in one of his houses in 1762. However, there is no evidence that the Mozarts knew Fischer in 1762 or that they stayed in one of his houses during that visit; this is another unsubstantiated claim that again ignores Leopold's inconvenient ‘Fierberggaßl’, thereby implicitly assuming (implausibly) that it is a corruption of ‘Tiefer Graben’. It also implies that Leopold mistakenly wrote ‘Tischler’ for ‘Fischer’ – a mistake Leopold is not likely to have made for a family that the Mozarts are said to have known.Footnote 53 The tax assessment of 1787–1788 shows that No. 323I had just two floors: a workshop and a storage room on the ground floor, and a single three-room apartment on the first floor that was a residence and unlikely to have been where the Mozarts stayed in 1762.Footnote 54 So this hypothesis has nothing in its favour, and is almost certainly wrong.

Yet Brauneis's revisionist (and as we now know, probably incorrect) view has been universally accepted in the secondary Mozart literature published since 1991. It is adopted by Heinz Schuler, for example, in his 1993 article on the Mozarts’ sojourn in Vienna in 1762.Footnote 55 Helmut Kretschmer, in his 1990 pamphlet Mozarts Spuren in Wien, followed Deutsch in placing the Mozarts in Ditscher's house (No. 321I) in 1762; but in a new edition published in 2006, Kretschmer changed to Brauneis's view, placing the Mozarts in Fischer's house.Footnote 56 This thesis was also adopted in a book published in 2004 by Rudolph Angermüller, who went so far as to omit the troublesome ‘Fierberggaßl’ from his quotation of the relevant passage in Leopold's letter.Footnote 57 But this revisionist view, in addition to its other implausibilities, overlooks the fact that both of Fischer's houses on Tiefer Graben had essentially the same small and square footprint as Ditscher's, and were just as unlikely matches for Leopold's description of the family's long and narrow quarters in 1762.Footnote 58

We have not yet been able to explain Leopold's ‘Tischler-Haus’. It is true that house No. 296I in Färbergasse belonged to the Tischler Georg Pämb for a short time in the late sixteenth century.Footnote 59 But this was certainly too long ago and too brief an association to have left any trace in the oral tradition of the eighteenth century, and there is no evidence that it did. We have found no evidence that the names ‘Tischler-Haus’ or ‘Tischlerisches-Haus’ were ever used at any time to refer to house No. 296I, to any other house on Färbergasse – or for that matter, to any house on Tiefer Graben. It may simply be that Leopold was mistaken or had misheard, or that the copyist of Leopold's letter mistranscribed what Leopold had written in the lost original. But if this is indeed what Leopold wrote, the error is puzzling, because he would have needed to give Hagenauer the correct house name as a return address: houses in Vienna did not yet have numbers in 1762. In spite of this caveat, the hypothesis that the Mozarts stayed in No. 296I is a good fit with all other known evidence, and we feel that a hypothesis with one unexplained piece of evidence is preferable to hypotheses that require reading Leopold's ‘Tischler’ as a corruption of ‘Ditscher’ or ‘Fischer’, imply a highly implausible reading of Leopold's ‘Fierberggaßl’ as ‘Tiefer Graben’ and ignore his description of their long and narrow quarters.

On the currently accepted view, when the Mozarts arrived in Vienna on 6 October 1762, they initially stayed for one or more nights at the inn ‘Zum weißen Ochsen’, then moved for the remainder of their visit to No. 323I in Tiefer Graben (today the site of Tiefer Graben 20), a house belonging to Gottlieb Friedrich Fischer. Our analysis suggests that no part of this view has any merit. As we have shown, there is no primary evidence for the claim, apparently first made in 1860, that the Mozarts stayed at ‘Zum weißen Ochsen’; the claim may well have been invented, although it has been remarkably persistent in the Mozart literature. The claim that the Mozarts stayed in one of Fischer's houses in 1762 likewise has no primary evidence to support it, and requires an implausible explanation for Leopold's reference to ‘Fierberggaßl’ (an explanation that is never explicitly stated, probably because of its implausibility). The combination of the two claims has no support in the known evidence and requires us to ignore the clear implication of Leopold's letter of 16 October 1762: that the Mozarts, upon arriving in Vienna, went directly to accommodation that had already been arranged by Herr Gilowsky, and that they remained there for the duration of their visit.

We propose instead that the Mozarts stayed in the house ‘Zum rothen Säbel’ in Färbergasse (296I, 361II, 333III, today Färbergasse 3), in the long and narrow wing that extended back from the main house. This hypothesis fits all known evidence, apart from Leopold's reference to ‘Tischler-Haus’, which remains unexplained. However, this does not seem to us a fatal problem. Although we do not take it as proven that the Mozarts stayed in ‘Zum rothen Säbel’ in 1762, as a working hypothesis it is far better than what has come before.

The Mozarts remained in Vienna until 31 December 1762, except for a visit to nearby Preßburg (Bratislava) from 11 to 24 December. They were twice received by the imperial family at the palace in Schönbrunn, and the children performed frequently in the houses of the upper nobility. Young Wolfgang had many formative musical experiences, hearing the finest musicians in Vienna and musical works in the most up-to-date styles; on 23 November he probably heard Gluck's new opera Orfeo ed Euridice.Footnote 60 The trip was successful enough from Leopold's point of view that he soon began planning a much longer and more ambitious tour of Europe that would take the family away from Salzburg from 9 June 1763 until 29 November 1766.

The stakes in the question of the Mozarts’ lodgings in 1762 may seem low. But for an iconic figure like Mozart, every scrap of biographical information can potentially have wide repercussions for the Mozart industry, including (perhaps especially) tourism. For example, the Hotel Tigra in Vienna now occupies the addresses Tiefer Graben 14–20, incorporating the sites of Ditscher's house (No. 16) and both of Fischer's (nos 18 and 20). Understandably, the hotel's website currently uses Mozart's (verified) stay in one of Fischer's houses in 1773 and his (incorrectly) alleged stay in one in 1762 as part of their marketing, even offering a ‘Mozart Package’ for visiting fans.Footnote 61 In this, they are simply trusting what Mozart scholars have repeatedly written; unfortunately, in this case, their trust has been partly misplaced. Our aim here has been to discard unsupported and implausible prior theories about the Mozarts’ lodgings in 1762, and to offer a new analysis, starting afresh from verifiable primary evidence.