1 Introduction: the what and the why of the project

The prosodic contrasts in pairs such as úpset, n. – upsét, v., cónvict, n. – convíct, v. are known as functional stress-shifts, also referred to as diatones. In some estimates (Dabouis et al. Reference Quentin, Fournier and Martin2014; Kiparsky Reference Kiparsky2016: 467) about 30 percent of the eligible homographic noun–verb pairs in Present-Day English (PDE) can alternate. Whether this type of prosodic contrast was an Old English (OE) inheritance, or a post-Middle English (ME) innovation is controversial, not least because some pieces of the diachronic account of English stress are missing and worth revisiting. So, one answer to the ‘what’ of this project are some lacunae in our records of pre-seventeenth-century stress with focus on functional stress-shifting.

The ‘why’ rationale of the endeavor is that verse evidence for possible prosodic changes in English is conspicuously absent from the records of the post-Chaucerian stretch of about 150 years. Halle & Keyser's foundational Reference Halle and Keyser1971 account of stress in early English verse jumps from Chaucer to Shakespeare and Milton, and so does the section on ‘Accentuation’ in Lass (Reference Lass and Blake1992: 89–90). Dobson's coverage of stress (1957, vol. II: 445–9) starts at 1500, officially, but his first relevant comments are to the late sixteenth century when the first English–English rhyming dictionary appeared (Levins Reference Levins1570). The testimony of orthoepists before the end of the sixteenth century (Dobson Reference Dobson1957, vol. II: 827–30, 1020–2) is mostly silent on stress, and the relevant section in Lass (Reference Lass1999: 128–33) also picks up from Levins’ (Reference Levins1570) Manipulus Vocabulorum. Further, even diachronic dictionary-based searches for diatones (Dabouis et al. Reference Quentin, Fournier and Martin2014; Hotta Reference Hotta and Haug2015) focus on post-sixteenth-century information. The otherwise valuable testimony of spelling is of little use for stress reconstruction; art verse remains the most promising source of prosodic information diachronically, so one of the aims of this study is to examine the way poets treat stress, and more narrowly, to attempt an extended record of the attestations of prosodic contrasts based on lexical category: nouns versus verbs.

Turning to the rapidly expanding ME lexicon, and especially late ME (1400–1550), we also present new records of the noun–verb pairs in an effort to see if the limited inherited stress-shifting model survives, and, if so, whether or how it accommodates the incoming loan vocabulary. The early history of differential stressing of nouns and verbs is discussed in the larger context of morphological versus phonological factors prior to the first contemporary records of stress (Levins Reference Levins1570). A renewed scrutiny of the data on early functional stress-shifting relates directly to a widely held view of the evolution of the parameters defining the direction of stress assignment in PDE, as elaborated in section 5, and highlights some of its problematic aspects.

The outline of the article is as follows. Section 2 presents evidence for the differential stressability of prefixed OE nouns and verbs. Section 3 adduces stress-shift data extracted from the ME poetic corpus, including a range of previously unidentified attestations. The relevant lexicographical records in the Dictionary of Old English (DOE) and the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) are presented in section 4, which explores the morphological and phonological properties of pairs recorded up to 1550. The discussion in section 5 reconsiders the continuity of functional stress-shifting, the link between prefixation and the rise of diatones after the middle of the sixteenth century, and underscores the effect of verbal prefixation on the changing balance between morphological and rhythmic components in the history of stress assignment. Some implications and prospects for further research are addressed in the final section.

2 Old English stress and noun–verb prosodic contrasts

In OE, primary stress falls on the first root syllable, marking the left edge of the semantic core of the word. This model of stress assignment, familiar from inherited vocabulary as in búsy, kéttle, bróther, ópen, útter, and historically shared with all other Germanic languages, is known as the Germanic Stress Rule (GSR). In OE it also applied to loanwords, often against the stress in the donor language: OE ábbot, Lat. abbā́dem ‘abbot’, OE cā́lend, Lat. kaléndae ‘first day of the month’, OE cándel, Lat. kandḗla ‘candle’, OE cúmyn, Lat. cumī́num ‘cumin’. All accounts of OE stress, including accounts based on the moraic trochee, acknowledge that OE primary stress falls on the first syllable of the root regardless of its weight.

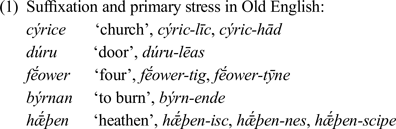

Inflectional suffixes do not affect primary stress. Derivational suffixes, even if they are transparently derived from independent roots, either etymologically or synchronically, e.g. (-)hād ‘-hood’; (-)lēas ‘-less’; (-)līc ‘-like, -ly’; (-)tȳne ‘-teen’, never shift the primary stress away from the base, though they may have secondary stress. The non-occurrence of primary stress on suffixes applies to all word types:

The stability of primary stress is testable in the verse: suffixed forms may behave like compounds, allowing the suffixal syllable to fill a metrical ictus, yet that syllable's onset does not alliterate by itself, indicating that it could not have held primary stress. Put differently, the primary stress-shifts triggered by Latinate suffixes as in Látin – Latín-ity, pérson – persón-ify, dráma – dramá-tic, a central feature of English stress today, are all post-OE innovations.

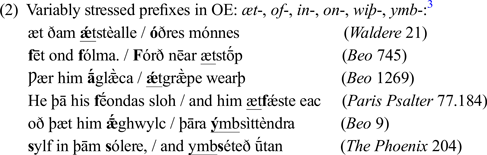

Prefixation presents a more complex picture. OE treated prefixed items differently depending on the stem's morphological class. Though often posited (Campbell Reference Campbell1959: 30–1; Hogg Reference Hogg1992a: 48–9), scribal evidence for prefixal allomorphy, e.g., ánd- vs. on-, bí(ġ)-vs. be-, ínn- vs. in-, depending on whether the prefix is attached to a nominal or verbal/adverbial base, is inconsistent (Minkova Reference Minkova2008: 26–7), leaving verse as the best source of information on prefixal prominence in nouns and verbs. Simplifying somewhat, there are three types of prefixes in OE: (a), prefixes which are never stressed, nor used in alliterating positions (be-, ge-, for-); (b), stressed adverbial prefixes which were originally attached to nominal stems (and- ‘against’, ed- ‘back’), and the verbs derived from them preserved the stress contour; and (c), prefixes which were stressed variably depending on the word class of the base:Footnote 2

The prefix æt- in the nouns ǽtstèalle ‘station, position’ in Waldere 21, or ǽtgrǣ̀pe ‘grasping, aggressive’ in Beo 1269 has primary stress and alliterates, while in the inflected verbs ætstṓp ‘stopped’ in Beo 745 and ætfǽste ‘cast/inflict hurt on’ cannot alliterate; similarly, ymb- in ýmbsìttèndra ‘(of) the neighboring people’ has vowel alliteration, while inflected ymbséteð ‘surrounds’ alliterates on [s-]. Nouns (and adjectives) derived with the prefixes in (2) are thus not subject to ‘prefix defooting’ (Selkirk Reference Selkirk1980).

OE verse supports an assumption of some degree of prosodic distinction of any unemphatically used nouns versus verbs; we return briefly to this in section 6. Further details aside for now, scholarly opinions converge on one point: functional contrast can be reconstructed beyond doubt only for prefixed items as in (2). They present the key metrical evidence for positing prosodic prominence asymmetry between finite verbs and other lexical words in OE, an asymmetry attested and much tested and discussed for PDE.Footnote 4

3 Stress-shifts in pre-1550 verse

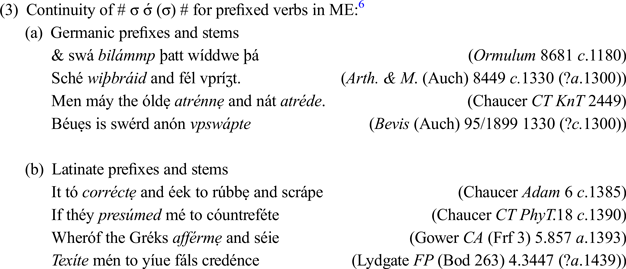

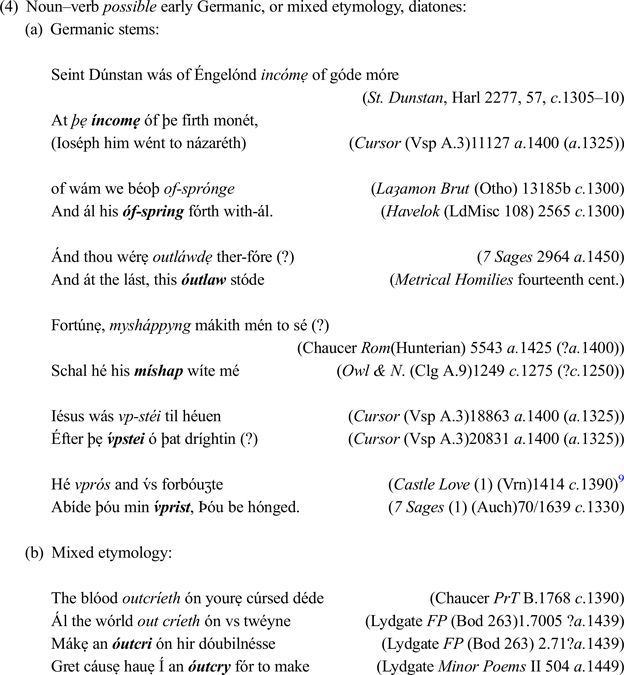

From the earliest strictly stress-alternating septenarius poems, through the blossoming of the tetrameter, and Chaucer's and Gower's innovative pentameter, prefixes on Germanic verbal bases remain uniformly unstressed. Newly borrowed non-Germanic prefixed verbs fit into the native framework; monosyllabic prefixes such as ad-, co-, ex-, pre- solidified and expanded the already well-established native pattern.Footnote 5

The usage recorded in (3) may seem like an effort to show the obvious, but the single most extensive documentation of stress-shifts in late ME verse (Nakao Reference Nakao1977: 33–4, 105–6) uses rhymes and marks stress on verbal prefixes (béwrappen ‘bewrap’, púrsu ‘pursue’, pórvey ‘purvey’) based on examples from ME alliterative verse; this then becomes part of the argumentation against the existence of noun–verb diatones in ME. We believe that both rhyme- and alliterative attestations should be left out of the evidential basis.Footnote 7

Recognition of the persistence of # σ σ́ (σ) # for prefixed verbs still leaves open the question of the coexistence of noun–verb prosodic contrasts in ME. For the native lexicon, the only Germanic noun–verb pair recognized as a diatone in Levins (Reference Levins1570) is outlaw, OE ū́tlàga. The first possible # σ σ́ (σ) # record for the verb is post-1400 and it can be ambiguous in the verse, in line with the treatment of compounds in stress-alternating verse. Searching for further contrasting noun–verb pairs is prohibitively time-consuming – the Middle English Dictionary (MED) allows no search option for ‘verse’ attestations – without the development of specialized tools.Footnote 8 Still, the placement of the boldfaced nouns in (4) would be hard to account for unless we assume continuity of at least optional functional stress-shifting; a (?) is added after a line if an alternative scansion cannot be ruled out:

In some of these pairs the verbal prefixes have subsequently become particles: come in, spring off, rise up, or the lexeme is obsolete: †upsty ‘resurrect’, but note that diatonic outcry (4b) is attested long before its assumed first date, mid-nineteenth century (Hotta Reference Hotta and Haug2015). Looking for more potential Germanic noun–verb contrasts, e.g., upcast, upset, upbrud ‘reproof’, uphold ‘support’, uplift, upspring ‘sunrise’, outcome, outryde, outfar ‘expedition’, outgate ‘exit’, outstrai ‘deviation’, has not been revealing; even if a pair is attested pre-1550, the stress placement is not recoverable.Footnote 10 The pickings are slim; nevertheless, the attestations in (4) clearly duplicate the OE pattern in (2).

For the non-Germanic portion of the lexicon, the only surviving diatones identified in Levins (Reference Levins1570) are rebel and record; the non-surviving ones are depute, divine, mischief, quarrel.

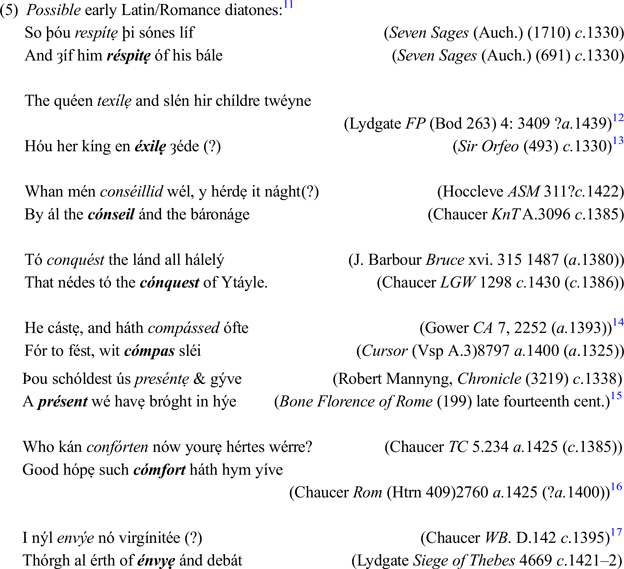

A manual search in the OED, the Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse (https://quod.lib.umich.edu/c/cme), as well as individual texts, yields attestations of noun-initial versus verb-final stress in verse that have not previously been considered potential inputs to the later history of diatones. The examples in (5) and (7) are arranged roughly chronologically by the date of the # σ́ σ # noun:

Isolating un-paired # σ σ́ (σ) # prefixed verbs, or # σ́ σ # prefixed nouns, in, roughly, pre-1400 records yields more examples, see (6). These cannot be considered ‘evidence’ for synchronic noun–verb contrasts since matching nouns for # σ σ́ (σ) # verbs, or verbs matching # σ́ σ # nouns, did not appear in the verse citations in the OED and the Corpus of Middle English Prose and Verse.

Additional pairs can be posited for the post-1400 period, yet once again the rarity of such contrastive noun–verb attestations in the verse does not allow more than a tentative conclusion regarding the item's ‘preferred’ prosodic contour in the poet's or the scribe's language.

The attestations in (4)–(7) illustrate options available to the poets; they are selective and do not preclude final stress for the nouns, typically in rhyme position; see fn. 11. In addition to the items identified here, desert and incense have been identified as diatones for the period 1567–1700, but we have not found any testable attestations of a noun–verb contrast for them in verse before Levins (Reference Levins1570).Footnote 22

This is a disappointingly short report on pre-1550 stress-shifts as found in verse. The demise of the ‘classical’ OE alliterative tradition with its robust link between stress and alliteration, and the transition to binary foot structure in ME isosyllabic verse, make the post-1150 verse materials much less informative about word prosody. The difficulty of tracking the metrical behavior of noun–verb pairs in the verse is compounded by the interference of paraphonological variants in the matching of the various metrical templates to the shape of lexical units whose prosodic contour is the target of discovery. The relative regularity of the metrical templates of some pre-1400 compositions, such as the septenarius of the Ormulum, or the tetrameters and pentameters of Chaucer and Gower, may allow more dependable, even quantifiable, parsing and testing of hypothetical prosodic contours of individual lexemes as in (6); see Duffell (Reference Duffell2018), Duffell & Billy (Reference Duffell Martin and Billy2004). Yet the problems of final -e's elision, optional inflectional syncope, stem-internal and compound-internal syncope, apocope in proclitics, [ɪ, ʊ] + [ə] contraction (synizesis), persist and appear to be much more text- and author-variable in the fifteenth century. Two of the leading poets in the fifteenth-century illustrate the hazards of any automated data-collection: Hoccleve counted ten syllables per line meticulously (Jefferson Reference Jefferson2000), but the iambic rhythm takes a back seat; and Lydgate adds idiosyncratic patterns such as pre-sonorant disyllabic long vowels in monosyllables, e.g., gold, child, fire, and schwa epenthesis in some [l] + [obstr.] coda clusters: -lk, -lf, thus follek for folk, selef for self. Both poets were fluent in Latin and French, a further complication.

Excluding attestations in rhyme, and discounting ME alliteration as evidence for prefixal stress, we have quadrupled the list of early diatonic pairs and have confirmed the likelihood of continuity of the OE subpattern. Nevertheless, the results still call for a quantifiable foundation for positing that the ME loanwords were undergoing change in line with the native diatonic model.

The sociocultural shift in the mode of versification in ME is accompanied by rapid accrual of Latin and OF/AN vocabulary. Quantifying the French and Latin contributions to ME, Durkin (Reference Durkin2014: 256–7) finds that 48 percent of the MED headwords and 44 percent of the OED headwords first recorded in ME are from French or Latin. The sheer bulk of new items in which the original stress assignment rests on different principles eventually impacts the entire prosodic system and complicates further the issue of inherited asymmetry of verbal versus nominal prominence. Searching for more information on the interaction of native and borrowed vocabulary, we turned to lexicographical records that might be illuminating with regard to the continuity and/or significance of the pattern of prefixed diatones in OE as adumbrated in (2).

4 Revisiting the lexicographical records on functional stress-shifting

The strongly articulated dismissal of the possibility of functional stress-shifting in late ME in Nakao (Reference Nakao1977: 152–61) emphasizes the discontinuity of the OE pattern of prefixal stress and yet posits a separate ‘rule’ for stress in prefixed items in late ME.Footnote 23 It is precisely the prefixed items and their relation to stress-shifting that we want to explore further. This section addresses data that may help us evaluate existing proposals on the continuity and triggers of diatonic stress-shifting for the period up to Levins’ (Reference Levins1570) first contemporary records of stress.

4.1 Stress and prefixal productivity in Old English

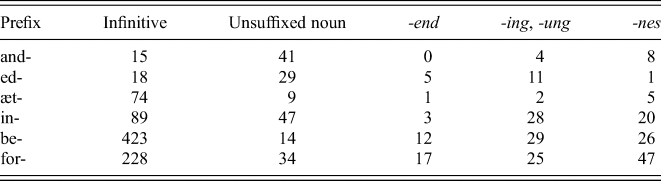

As demonstrated in section 2, testable stress-shifting in OE occurs only within a subset of the prefixed items. Turning to the correlation between prefixal stress and prefixal productivity in the OE lexicon, it is clear that some prefixes combine much more readily with either nominal or verbal bases. A DOE search for the stress-shifting prefix æt- shows 74 verb headwords versus only 9 noun headwords. A search for in- shows 89 verbs and 47 nouns. We exclude prefixed verb derivatives in -end, -ing/-ung, -nes – they are not used in the poetry.Footnote 24

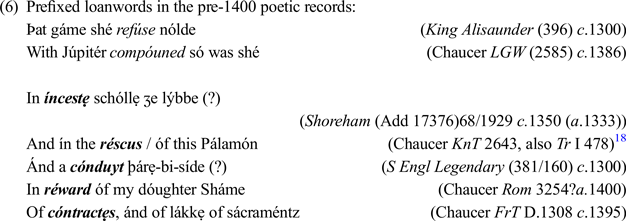

The search for ‘exact’ numbers is often hampered by ambivalence on prefixal versus adverbial units, prompting an analytical equivalence between prefixed nouns and compounds (Kendall Reference Kendall1991: 176).Footnote 25 With this preamble in mind, we collected the complete set of DOE entries for two prefixes, and- and ed-, which are always stressed, two stress-shifting prefixes, æt- and in-, and the consistently unstressed be- and for-. Table 1 presents the raw data on the correlation between prefixal stress and prefixal productivity.

Table 1. DOE lexical entries with and-, ed-, æt-, in-, be-, for- (types)

It is only with and- and ed- that prefixed nouns (and adjectives) outnumber the verbal forms and they all preserve the prosodic contour of the input, e.g. éd-lḕan ‘reward’ (c.300 tokens) versus éd-lḕanian (8 tokens), also ge⋅éd-lḕanian, ge⋅éd-lḕanod, éd-lḕaniend, ge⋅éd-lḕaniend, éd-lḕanung, ge⋅éd-lḕanung. Both and- and ed- are lost very early in ME (OED, Molineaux Reference Molineaux2012), leaving OE ánd-swaru, ánd-sawarian, ‘answer’, n., v. as the sole trace of that prefixal pattern.

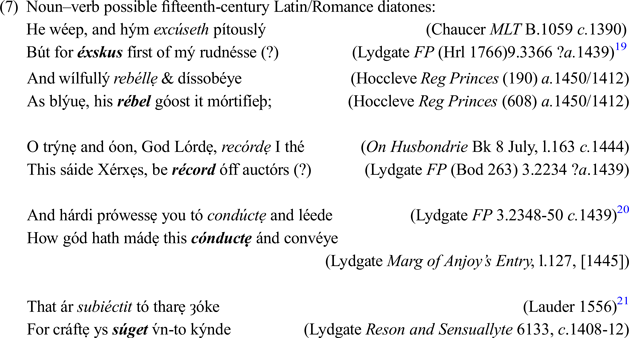

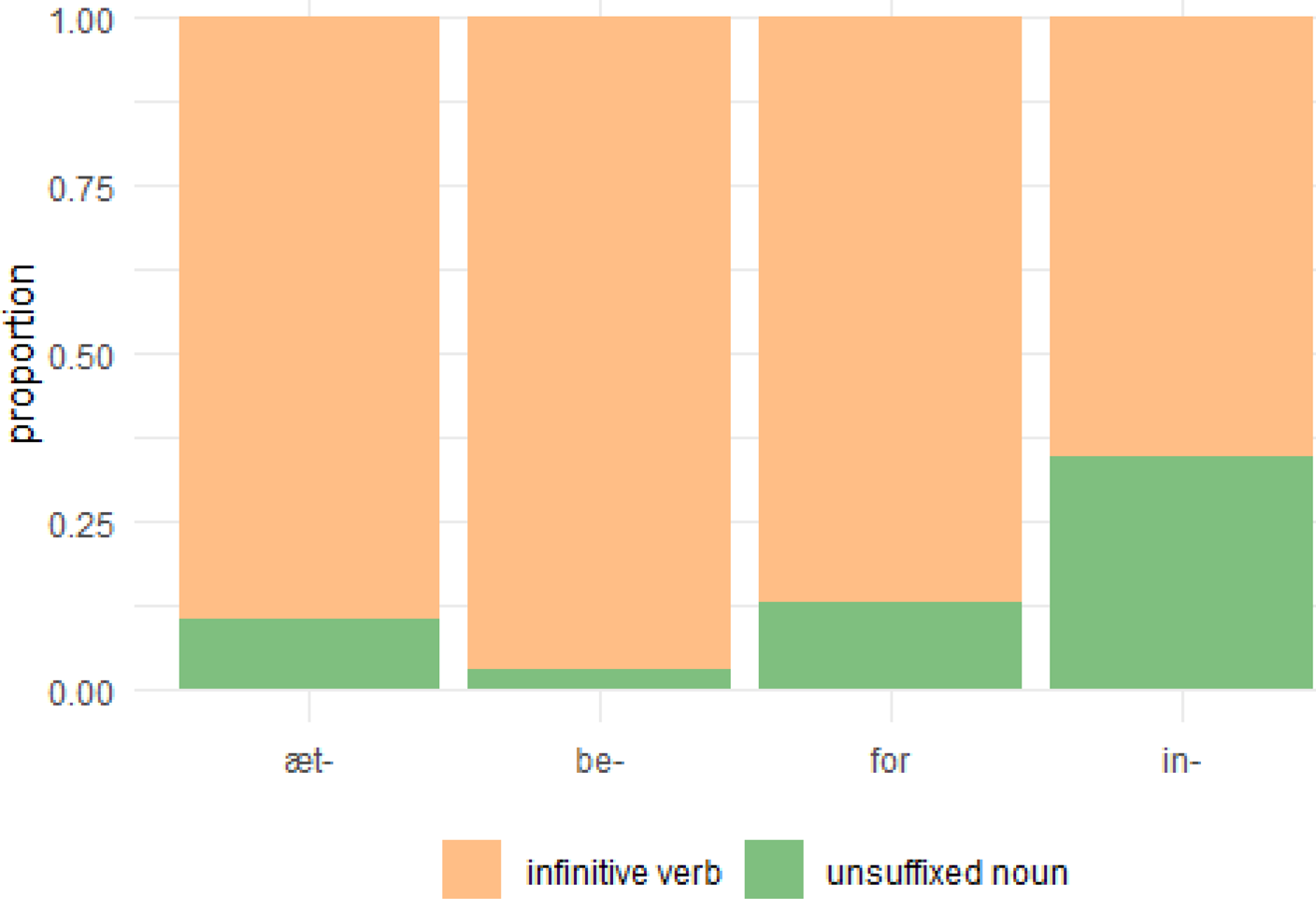

For the variable and the unstressable prefixes, noun prefixation in OE is a more limited pattern compared to suffixation, both in terms of types and in terms of tokens, e.g. æt-hrīnan, v. ‘to touch’ (c.110 tokens), æt-hrine, n. ‘touch’ (17 tokens); belimpan, v. ‘pertain, occur’ (c.225 tokens) vs. belimp, n. ‘occurrence’ (11 tokens). In a lexical basis of 16,694 nouns, González Torres (Reference González Torres2010: 23) reports that ‘suffixation outnumbers prefixation at practically a ratio of 9 to 1 [(351 derived by prefixation and 3,137 by suffixation)].’ This prompts us to set aside the suffixed noun forms in table 1. Focusing just on the noun–verb ratios for the other two types of prefixes, stress-shifting æt-, in-, and the unstressed be-, for-, the ratio graph in figure 1 illustrates the strong preference for prefixes to attach to verbal stems.

Figure 1. Noun–verb ratios for æt-, be-, for-, in-

The clear preference for monosyllabic prefixes to combine with verb stems in the Germanic lexicon creates a competing model of stress assignment in which left-edge word-alignment is overridden by the presence of a (C)V(C)- prefix. The numerically most productive prefixes in table 1, be- and for-, plus over 2,000 ge- entries in the DOE, are thus entirely outside the stress template, irrespective of the grammatical nature of the stem. This, we believe, is a plausible lexicon-based starting point for assessing the role of prefixes in the historical trajectory of stress assignment.Footnote 26

4.2 Germanic versus Latin and OF/AN prefixes in Middle English

In ME the productivity of Germanic verbal prefixation continued along with the development and spread of phrasal verbs and the obsolescence of some OE prefixes (Lutz Reference Lutz1997; van Kemenade & Los Reference Kemenade and Los2003; Schröder Reference Schröder2008; Molineaux Reference Molineaux2012; Thim Reference Thim2012). Some monosyllabic prefixes (and-, æt-, ed-, forð-, on-, or-, oð-, þurh-, ymb-) lost their productivity during ME and some Germanic prefixes merged with their Romance homophones: mis-, in-. Footnote 27 The reduced allomorph [ǝ-] of OE ǣ-, at-, on-, or-, and Lat. ad-, en-, ends up as ‘not a real prefix’ (Marchand Reference Marchand1969: 139), though new derivatives, all in predicative use (aflame, alee, aswoon), continue to be coined in ME.

The loss of predominantly heavy, stressable OE prefixes (Molineaux Reference Molineaux2012) in ME increases the proportion of unstressable prefixes in the lexicon. The inseparable and always unstressed be- is very robustly productive. Petré (Reference Petré2006) records a steady rise in verbal be- prefixation up to 1350; a quick check of the timeline of the frequency of be- verbs in the OED shows a rising trajectory with both native and mixed etymology forms (begrudge, betray, bedoubt, beglue). After 1350, the numbers are doubled and even trebled, reaching a peak for 1600–50. The same OED search for verbs with for(e)- shows a peak in the 1350–1400 span for both native and mixed etymology verbs such as forchase, foreclose, forjoust. Such overlaps, as well as the density of new derivatives with unstressed Germanic prefixes, potentially enriches the input for noun–verb pairings both in the Germanic and in the new Latin and Romance vocabulary for the extended ME period.

A further rationale for a closer look at the lexicographical information for our period comes from the database of diatonic pairs in PDE. Hotta (Reference Hotta and Haug2015: 16) expands the earlier list in Sherman (Reference Sherman1975) from 150 to 235. Only 3 out of the 69 pre-1800 recorded pairs (torment, cement, bombard) are not prefixed items. Of the remaining more recently attested pairs, only 12 are not transparently prefixed. The role of prefixes in PDE diatonic stress assignment has been recognized (Hurrell Reference Hurrell2001), and the ‘morphology hypothesis’ (Fournier Reference Fournier2007; Dabouis & Fournier Reference Dabouis and Fournier2017) has been tested and confirmed statistically, but pre-1550 data were not included in these studies.

4.3 OED data on prefixed nouns and verbs in ME

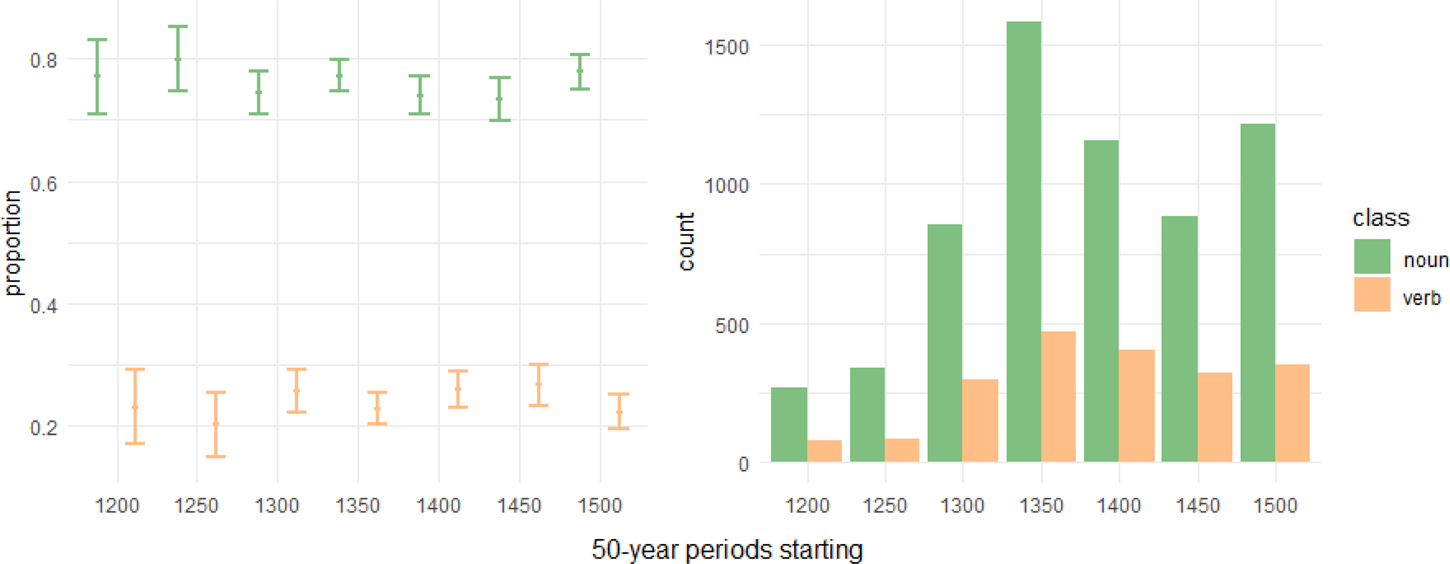

Turning to the attestations of prefixed nouns and verbs in the OED, we present in figure 2 a graph showing the first attestation dates that the OED cites for Latin/Romance nouns and verbs borrowed between 1200 and 1550. We chose the 1550 cut-off date, 20 years before the publication of Levins’ Manipulus vocabulorum (Reference Levins1570), assuming that he was recording prosodic patterns typical of his adult speech. We have filtered out compounds, suffixed and derived forms, as we are interested primarily in base forms; we have also attempted to filter out monosyllables,Footnote 28 as they do not give any evidence for stress.

Figure 2. Proportions and counts for borrowed Latin/Romance nouns and verbs. For visual clarity, here and in figures 3–4, x-axis labels for the date of first attestation have been abbreviated: 1200 refers to the period 1200–50; 1250, to 1250–1300; etc.

A total of 8,295 words comprise this dataset. As we see, the number of non-Germanic nouns borrowed into ME vastly outnumbers that of verbs, 6,297 to 1998. We find that about 76 percent of all borrowings are nouns – and this trend is stable, with none of the half-century periods under consideration diverging notably from this proportion. The result is congruent with an earlier study sampling MED entries A–O first recorded 1100–1500, finding that ‘the bulk of lexical borrowing from the Romance languages (more than 2/3) consists of nouns’ (Dekeyser Reference Dekeyser, Kastovsky and Szwedek1986: 261); the same study also records a drop in OF nominal borrowing from 87.5 percent of all Old French (OF) loans before 1200 to 61.25 percent in the latter half of the fifteenth century.

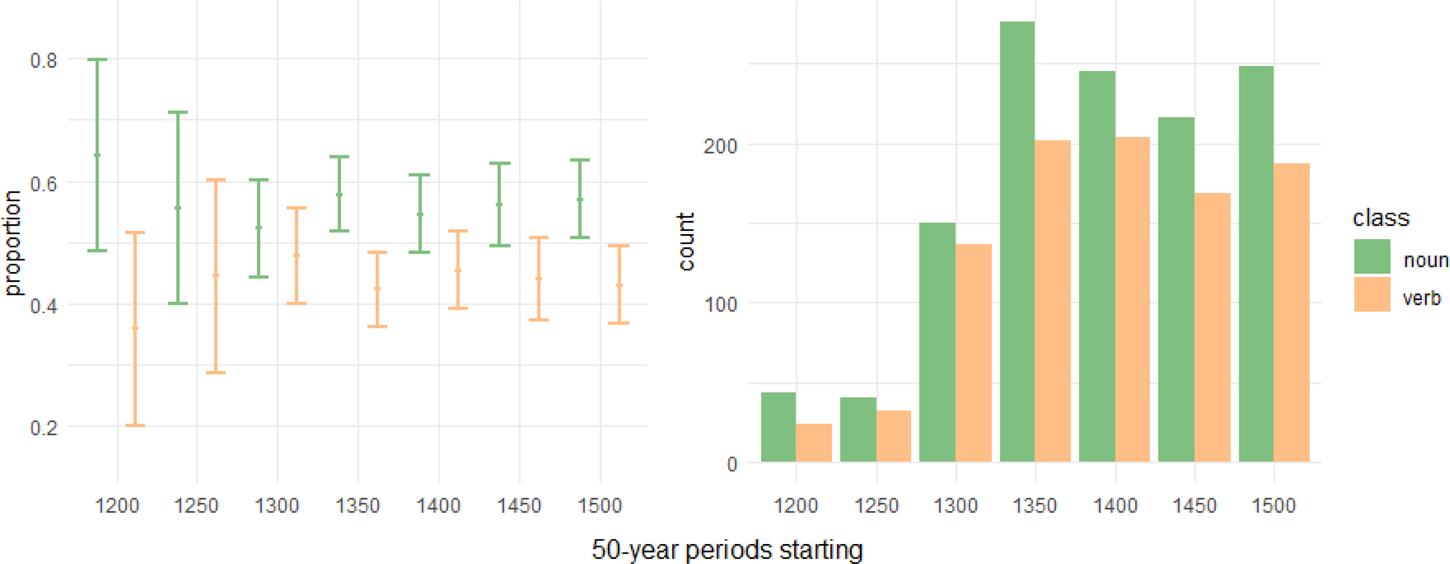

The picture is very different when we consider only prefixed items. Figure 3 displays a subset of the data presented in figure 2 where we have filtered out all words which, orthographically, must be unprefixed. A total of 2,173 words comprise this dataset, including 256 noun–verb pairs.Footnote 29 Under these conditions, we find that prefixed nouns and verbs were borrowed into ME at much more similar rates. Though even within the prefixed population more nouns are borrowed than verbs (1,218 to 955), there are 50-year spans where the margin of error bars for nouns and verbs do overlap, unlike in figure 2.

Figure 3. Proportions and counts for prefixed, borrowed Latin/Romance nouns and verbs

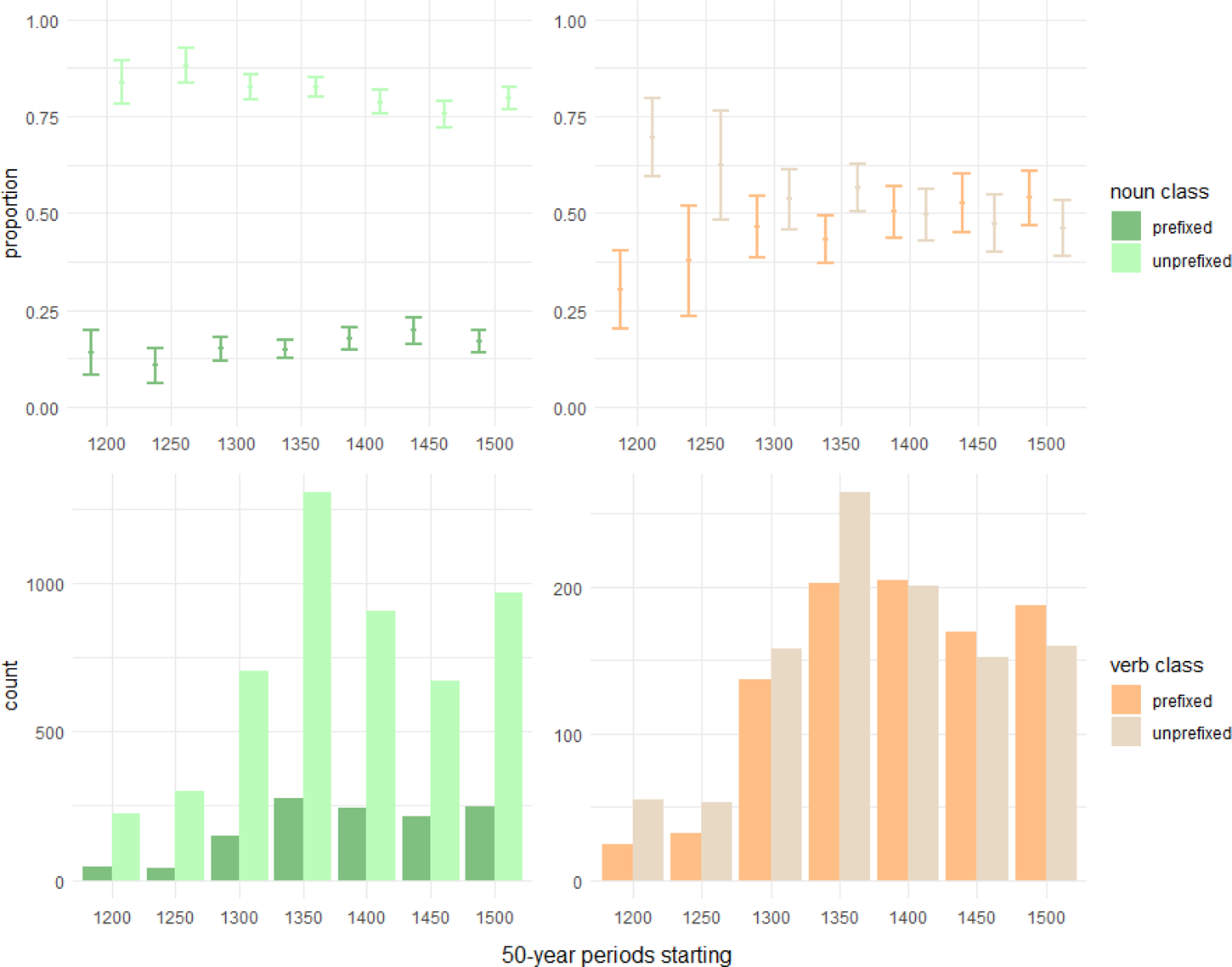

It is when we compare prefixed to unprefixed nouns and prefixed to unprefixed verbs that the picture becomes most clear. As shown in the bottom left panel of figure 4, prefixed nouns are a minority of borrowed nouns, 1,230 to 5,144 across the 350-year span, and the margin of error bars for the proportions in the upper left panel do not overlap. In contrast, the bottom right panel shows that prefixed verbs are very close in number to unprefixed verbs, 957 to 1,045 for the same period, and that while the margin of error bars for the first 50-year span for verbs do not overlap, this is not so for any of the following spans, as the proportion of prefixed verbs continuously increases.

Figure 4. Top, proportions and bottom, counts for prefixed, borrowed Latin/Romance nouns and verbs. Nouns are presented on the left and verbs on the right.

Considering the root-aligned stress pattern of ME, the righthand charts thus show that there has been consistent lexical pressure to model verbs as a sublexicon with noninitial stress. Yet, before moving onto the discussion, we wish to address the thought-provoking alternative possibility raised by a reviewer: prefixed verbs could have been more readily borrowed because they fit the established, right-strong stress pattern while prefixed nouns were blocked by strong left-strong stress. The best response we can give relies on what we know of borrowing patterns in contemporary languages. Though we are not experts in this field, we are unaware of research examining purely phonological factors that facilitate loanword adoption. That said, the idea that phonological factors may inhibit borrowing seems to us difficult to defend, as, impressionistically cross-linguistically, nearly every form of phonological process has been deployed to nativize borrowed, ungrammatical structures.Footnote 30

5 Discussion

Our first remit in this article was to track and record evidence for the perseverance of the inherited OE subpattern of prefixed noun–verb stress-shifts in ME verse. Our expectations were partially validated in section 3; we more than quadrupled the known number of individual lexical items whose placement in ME verse bears out the hypothesis of continuity, yet due to the scarcity of data, the results fall short of statistical verifiability. The addition of lexicographical information (figure 4) reinforces the hypothesis of continuity by documenting that, whereas borrowed nouns came into ME with a preponderance of them unprefixed, prefixed verbs grew in proportion to unprefixed verbs quite early on. Taken together, these two angles on the evidence endorse a hypothesis that, in its earliest stages, functional stress-shifting was predicated on prefixation, in line with the ‘morphological hypothesis’ (Fournier Reference Fournier2007; Dabouis et al. Reference Quentin, Fournier and Martin2014) formulated on the basis of later data. This inquiry into the early history of diatones suggests a significant lexical pressure to model verbs as a sublexicon with noninitial stress which affects the account of the overall evolution of the prosodic system of English.

Examining stress patterns up to and including Chaucer, but not beyond, Minkova (Reference Minkova1997) rejected earlier proposals that either the OF/AN, or the Latin stress rule had displaced the left-edge Germanic stress in pre-1400 English; similarly, Redford (Reference Redford, Fikkert and Jacobs2003), adding a hypothesis of ‘hovering’ stress for doublets in verse.Footnote 31 McCully (Reference McCully2002) looks at post-1500 OED data, and McCully (Reference McCully, Fikkert and Jacobs2003: 355) talks of ‘the phonological crisis provided by the spectacle of incoming romance rules’, and provides arguments against what he labels ‘the catastrophe model’; his focus is on evaluating the empirical validity of competing descriptive models, but as far as source ME data go, it is still Chaucer/Chaucerian versus later, or contemporary English, as in the most recent study of historical noun–verb stress contrasts (Hofmann Reference Hofmann2020). Should one need further justification for our diachronic fact-finding mission, one particular recurrent statement about the chronology of prosodic change in English attempts a more explicit timeline for the stress innovations in PDE:

(8) Sequence of changes in stress parameters:

1400: Foot direction Leftward, Main stress Left (as in OE)

1530: Foot direction Rightward, Main stress Left

1660: Foot direction Rightward, Main stress Right

(Cited from Fikkert, Dresher & Lahiri (Reference Fikkert, Dresher, Lahiri, Kemenade and Los2006: 146); also in Dresher & Lahiri (Reference Dresher, Lahiri, Fortescue, Jensen, Mogensen and Schøsler2005: 82–3), Dresher (Reference Dresher2013: 61), Lahiri (Reference Lahiri, Honeybone and Salmons2015: 231), Dresher & Lahiri (Reference Dresher and Lahiri2015)Footnote 32

Obviously, any attempt to pin down cut-off dates has to draw arbitrary lines in a continuum, yet it is quite clear why the history of noun–verb contrasts and other pre-seventeenth-century developments call for a magnifying glass.Footnote 33 Again, the consensus on the issue of Main Stress Left / Align-L (Root, PrWd) is that the exposure to the borrowed lexicon did not affect stress parameters before the sixteenth century. Recall also that in ME, most unprefixed disyllabic loanwords followed the GSR by default, except words borrowed directly from OF in which the ultima was not a light syllable (L), [-ǝ]; these items are readily assimilated to the GSR. All Latin disyllabic words obeyed the GSR, as did trisyllables with a light penult:

(9) Stress in disyllabic monomorphemic loans:

-

With trisyllabic and longer non-Germanic words the patterns are more varied, but in that set, too, the potential of left-edge stress for underived words exists for σ́ L σ strings as in ábacus, Lúcifer, lítany, símile. Alternating stress in borrowed derivatives: crèatúre, pìlgrimáge, chìvalríe is another prosodic contour compatible with OE suffixed words: bíterlī̀ce ‘bitterly’, crísten-dṑmes ‘of Christianity’. These structural overlaps and the fact that English continued to be the first language of the majority of the population underlie the entrenchment of initial stress in the unprefixed lexicon throughout ME.

Against this background, the new component in the timeline is the persistent violation of left-alignment for a considerable portion of the lexicon: the prefixed verbs irrespective of etymology, plus the overwhelming majority of paired prefixed nouns. While prefixes are accommodated by extrametricality/defooting for verbs, some prefixes lose their extrametricality in nouns in favor of satisfying Main Stress Left / Align-L (Root, PrWd). This was already the case in OE, providing a landing site for the expansion of the diatonic model in ME. On the other hand, the new non-Germanic prefixed lexicon strengthens prefixal defooting, creating ongoing competition between the two types of stress assignment. We submit, therefore, that the trajectory of stress-shifts in (8), which leaves the OE system intact into the middle of the sixteenth century, must be elaborated.

To recap, some factors that suggest a revised account of the ME ‘roots’ of functional stress-shifting are:

◊ Survival and considerable growth of OE unstressable prefixation (e.g. be-, for-, [ǝ-])

◊ Extrametricality of all borrowed monosyllabic prefixes in ME

◊ Different noun–verb ratios for unprefixed and prefixed loanwords

Additional factors that influence the trajectory of diatonic stress-shifts are:

◊ Decreased transparency of borrowed monosyllabic prefixes, see fn. 5

◊ Persistence of left-alignment for nouns, both prefixed and unprefixed

◊ Increased exposure to stress-attracting suffixation

The combination of these factors presumably leads to the weakening of the essential principle of the GSR:

◊ Demotion of Align-L (Root, PrWd)

The ranking of these factors is a matter we cannot address yet, nor do we have the numbers or methodologies that might clear up the picture (Elkins Reference Elkins2020; Zuraw et al. Reference Zuraw, Lin, Yang and Peperkamp2021). Our findings nevertheless support a hypothesis that treats prefixes as the fifth column undermining the GSR from the earliest records on. The ‘future’ of diatonic pairs is foreshadowed by the prosodic asymmetry of prefixed nouns and verbs in OE. In ME, only a very small subset of OE prefixed nouns survives, while the verbal portion of the prefixed lexicon gains strength.Footnote 34

All attempts to identify the factors for the rise and growth of diatones in English, a spectacularly unidirectional graph (Hotta Reference Hotta and Haug2015), take the middle of the sixteenth century as their starting point. We revisited the whole issue of how ME poets chose to position prefixed words and the status of these items in the ambient lexicon. The findings are thus relevant to the two central prosodic issues for ME: continuity of root-based primary stress, and continuity/evidence for variably stressed prefixed nouns and verbs. Going back to Sweet (Reference Sweet1888: 887), Jespersen (Reference Jespersen1909: 174–82), Halle & Keyser (Reference Halle and Keyser1971: 112–18), Kastovsky (Reference Kastovsky1992: 361), we read that the OE model in (2) continued in Middle English.

(10) Halle & Keyser on dating the Middle English stress-shifts:

… the generalization of the Stress Retraction Rule did not at first extend to verb-noun pairs of the permit type … it is not until 1634 that we have reliable evidence of stress retraction in the nouns of this class. (Reference Halle and Keyser1971: 112, n. 16)Footnote 35

… in the earlier stage of the language, verb-noun stress doublets did not occur in the Romance portion of the vocabulary but were restricted to the Germanic portion. (Reference Halle and Keyser1971: 118)

Similarly, recall that Nakao's study concludes that ‘There is little or no coherent correlation observable between prefixal stress and lexical categories’ (Reference Nakao1977: 91).Footnote 36 Our renewed, closer look at relevant pre-seventeenth-century data highlights previously ignored morphological and lexical factors in play throughout the history of the language. This leads us to suggest that the diatonic pattern was never interrupted, though the metrical evidential basis for the assumption was found to be slim, slight and slender. That part of the data remains disappointingly unobtainable.

Nevertheless, the newly documented high rates of verbal prefixation in the lexicons of OE and ME reveal a fresh angle on the role of prefixed verbs: they have been destabilizing Align-L (Root, PrWd) from OE on. At the same time, while newly borrowed, prefixed nouns did enter the ME lexicon, the majority of borrowed nouns were not prefixed and so immediately or near-immediately conformed to the native stress pattern.

This is in partial agreement with Kiparsky (Reference Kiparsky2016: 467) who comments on the various approaches to the growth of diatones, stating: ‘This is obviously not sound change but the analogical spread of a morphological stress rule within the lexicon.’ Is there a phonological component? Kelly (Reference Kelly1988: 213) noted the relevance of stem codas for stress contrasts in noun–verb homographs in PDE, and Minkova (Reference Minkova1997) treats ME nouns and verbs separately on account of the lag-time in inflectional loss in verbs, compared to nouns, an observation bolstered by subsequent digging into the prevalence of alveolar codas in verb loans exhibiting the shift (see also Sonderegger Reference Sonderegger2010/2016: 415; Hotta Reference Hotta and Haug2015). It is possible that phonological factors were involved in the non-survival of earlier diatonic pairs as in envy, exile, council cited in (5). Thus, we are not ready to reject the ‘sound change’ aspect of the early development until we have more data on the phonological details of the material in figures 2–4.

6 Implications and prospects

Recent research that looks into ME verse evidence for the noun–verb prosodic asymmetry (Hofmann Reference Hofmann2020) seeks to establish the effect of rhythmic context for the attested patterns as found in Chaucer. Hofmann's tentative conclusion is that rhythmic context is an additional factor in the behavior of verbs and nouns. However, he does note (2020: 480) that other conditioning factors, including derivational morphology, have not been addressed, singling out the prosodic status of prefixes as one of those possible or probable aspects of the reconstruction that has not been dealt with. We concur, and this article endeavors to address prefixation and its interaction with prosody, meter and the structure of the lexicon.

Our findings here are not as complete as we would like. Consider Molineaux's (Reference Molineaux2012) argument that the heavy, stressable, monosyllabic prefixes of OE were lost in the transition to ME, motivated by stress-clash avoidance.Footnote 37 The extent to which this avoidance is a factor in the accommodation and later history of borrowed prefixes is unclear. The majority of prefixed borrowed words (1200–1550) have heavy prefixes, with already reduced OF/AN de-, pre-, pro-, re- as our only exceptions. However, words with these light prefixes comprise a large portion of our data, which would align them with the robustly productive and unstressable a-, be-, for- in the native input. Moreover, the issue of prefix weight is not fully addressable without considering the weight of the first post-prefixal syllable and the composition of its onset. This involves future work on the creation of a database that includes the OED's IPA transcriptions; see Smith (Reference Smith and Farrell2016).

The roots and causes of the spread of stress-shifting in sixteenth–twenty-first-century vocabulary remain a troubled topic. Although the focus of this study is on continuous or newly emerging functional prosodic contrasts as in présent, n., adj. – presént, v., both the methodology and the results bear directly on mapping the overall evolution of stress patterns in earlier English. The correlation between morphological structure and diatonic shifts in homographic pairs is addressed here only on the level of word stress. The extent to which the assumed presence of diatones in OE and ME correlates with the general prosody of the language with respect to higher-level prominence for different word classes is not a straightforward matter either. In OE, variable verb-placement in different types of clauses (VS, VO, SV, OV) may interact with right prominent phrasal stress, and the type of verb (auxiliary, pre-modal, or full) also affects its prosodic prominence. Thus, despite the long tradition of citing prefixed category-specific shifts in OE (Campbell Reference Campbell1959; Hogg 1992; Lass Reference Lass1994) for the variably stressed prefixes, further discussion of the prefixation condition for # σ́ σ- in nouns and adjectives versus # σ σ́- in finite verbs has to take into account the well-documented differential behavior of unprefixed verbs and nouns/adjectives as in gripe ‘grip, sword’ vs. grīpeð ‘grasps’ or cearu ‘care, sorrow’ vs. cearað ‘cares, is anxious’:

The pattern of non-alliteration of unprefixed verbs illustrated in (11) is not categorical; in Beowulf, 23.6 percent of the finite verbs alliterate (Getty Reference Getty2002: 62).Footnote 38 Finite verbs are treated differently verse-initially and verse-finally, and the main alliterative templates (a b : a x, or a a : a x) preclude correspondence between alliteration and metrical prominence at the end of the b-verse. Again, the verbs’ variable behavior in verse depends on their position in the clause; initial, medial, final; on the nature of adjacent lexical items in the verse; and not least, on the ‘poetic register’, a topic of much attention and disagreement; see Bliss (Reference Bliss1967), Russom (Reference Russom1987: 33–8, 2022), Kendall (Reference Kendall1991: 26–36), Los (Reference Los2015: 226–9), Griffith (Reference Griffith2016), Donoghue (Reference Donoghue2018: 143–51) and references there. For PDE, Kelly & Bock (Reference Kelly and Kathryn Bock1988) turn to metrical evidence to corroborate their experimental findings. They report that the alignment of words with strong beats depends on grammatical class: monosyllabic nouns fill strong metrical positions 94 percent of the time in samples of Milton's and Shakespeare's verse, while verbs fill such positions only 76 percent of the time.

How these questions play out in ME is still unclear; they warrant a separate treatment. In this connection we note that experimental research on the prosodic asymmetry in PDE (Kelly & Bock Reference Kelly and Kathryn Bock1988; Guion et al. Reference Guion, Clark, Harada and Wayland2003, confirmed in Smith Reference Smith and Farrell2016) finds that disyllabic nouns are significantly more often trochaic, while disyllabic verbs are iambic.

Finally, the role of lexical frequency in the earlier history of functional stress-shifting also remains murky. Phillips (Reference Phillips2006: 121) found that ‘low entrenchment’ of the new, low-frequency homographic words allowed nouns to get initial stress – they were treated as ‘new’ words. Hotta (Reference Hotta and Haug2015) finds the frequency effect ‘difficult to evaluate’, and Sonderegger (Reference Sonderegger2010/2016) makes a convincing case for combining the frequency factor with the structural factor of prefixation in the account of the smaller diatonic database in Sherman (Reference Sherman1975). How these positions jibe with the high productivity and token density of items with inherited unstressable prefixes (be-, for-, a-) has not yet been elucidated. Further, current research suggests that separate lexical entries are maintained for not only phonologically identical content words (Gahl Reference Gahl2008) and inflectional morphemes (Plag et al. Reference Plag, Homann and Kunter2017), but also homophonous, homographic, zero-derived noun–verb pairs (Lohmann Reference Lohmann2018, Reference Lohmann2020a, Reference Lohmann2020b). Though we will likely never know if the durational correlations discussed in these articles can be projected back to OE and ME, it is clear that lexical frequency should not be ruled out as a factor without cause.