1 Introduction

The apostrophe is certainly the Cinderella in the set of marks of punctuation insofar as grammarians have traditionally hesitated about its adscription to a particular linguistic domain, whether an orthographic issue according to Hart, a syntactic aspect according to Greaves or an independent element to be the topic of a separate chapter according to Jonson (Salmon Reference Salmon and Lass1999: 23).Footnote 2 This controversy is surely the result of the plethora of uses that this symbol was put to after its sudden irruption in English writings. Today, the apostrophe is used in the contraction of auxiliaries (e.g. it's, it isn't), the marking of the genitive case (e.g. the king's men) and in the formulaic expression o'clock. However, the symbol endorsed a variety of uses in its early history, such as the marking of other elisions (e.g. th'inward, th'onely), of plural nouns (e.g. boy's and girl's) and of the past tense forms of regular verbs (e.g. lov'd and lik'd), to name just the most significant. The orthographic system, and the use of the apostrophe in particular, was still incipient in the sixteenth century and its variety of functions are a vivid indication of the lack of a standard at the time. Robert Lowth (Reference Lowth1763: 169) was particularly aware of this fact, acknowledging the imperfect status of punctuation when he regretted that in view of the few precise rules holding without exception in all cases, ‘much [had to] be left to the judgement and taste of the writer’.

Even though the apostrophe has been claimed to be derived from the virgule in some early sources (Tannenbaum Reference Tannenbaum1930: 145), it is more plausibly a symbol of Greek and Latin provenance (André Reference André2008: 3) that English most likely borrowed from French and Italian, where it had a wide circulation (Crystal Reference Crystal1995: 203). The apostrophe in English documents dates back to the second half of the sixteenth century, first introduced as a marker of certain forms of elision, as in th'onely ‘the only’ or o'man ‘woman’, where we find that there is no consistency in the position of the apostrophe, with it being found earlier or even later than the point of elision (Petti Reference Petti1977: 27). In this incipient stage, this symbol was exclusively used by the learned printers of the period and Jonson, among others, regretted that its omission was then more frequent than its appearance through negligence (Salmon Reference Salmon and Lass1999: 40). This early phase gave way to the actual dissemination of the apostrophe to other orthographic environments, the contraction of modal auxiliaries and the expression of the genitive form of the noun being the most obvious cases. The general use of this symbol in the genitive case is already attested towards the middle of the seventeenth century,Footnote 3 becoming well disseminated in the course of the following century.Footnote 4 The genitive plural form, however, is erratic throughout the whole eighteenth century to the extent that the regular plural -es could appear either with or without the apostrophe (Leonard Reference Leonard1962: 193‒4).

This use of the apostrophe developed alongside the so-called greengrocer's apostrophe, the apostrophe being placed before the terminal <s> of a plural noun, as in orange's, apple's or the odd form asparagu's (Oxford English Dictionary [OED henceforth], s.v. greengrocer's apostrophe n.). Curiously enough, the use of the apostrophe for the expression of the nominative plural extended well into the latter part of the twentieth century. In itself, it has been a 400-year history characterised by the grammarians’ increasing concern about the growing dissemination of this practice in the English language. Seventeenth-century grammars systematically disregarded this particular use of the apostrophe, focusing instead on its uses either to mark elisions or to express the possessive case. It was in the eighteenth century when grammarians started condemning the use of the apostrophe for the expression of plural number, as in Robert Baker's Reflections on the English Language (Reference Baker1770: 25), where he explicitly inquired ‘for why should an Apostrophe be placed where there is no letter omitted?’ The prescriptive attitudes against this use of the apostrophe gained traction in the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, coinciding with the wider distribution of the apostrophe in these contexts. The issue was then a matter of debate in English and the general trend was to proscribe this use of the apostrophe, considering it as aberrant (Alford Reference Alford1864: 22) or errant practice (Burchfield Reference Burchfield1996: 61). The twentieth century was, as Beal describes, characterised by zero tolerance of the greengrocer's apostrophe as a reaction to the general concern and controversy generated at the time on the assumption that it was an illiterate feature and a symptom of a decline in literacy (Beal Reference Beal2010a: 61‒2).

This review of the apostrophe sheds light on the growing reputation of this symbol as a versatile device for a wide array of purposes and the grammarians’ dissatisfaction with this state of affairs in the Late Modern English period, the eighteenth century in particular. One can easily imagine, on the one hand, the printers’ despair at the unresolved condition of apostrophes in the period when exceptions were more frequent than the rule and, on the other, the grammarians’ disturbance in their attempt to bring some order to the chaos stemming from the catch-all dimension of the symbol. The period 1650–1750 was, then, crucial, featuring the conflation of the different uses of the apostrophe and the starting point of the eventual configuration of the present-day uses of the symbol. The question is whether the present-day situation is the result of the printers’ usage or of the grammarians’ precepts. Unlike other grammatical issues, grammarians were well behind printers in this very case and their seventeenth- and eighteenth-century precepts show that they had difficulty keeping up with the pace of this multifaceted symbol. Salmon, for instance, acknowledges that ‘printers were more progressive than grammarians’ (Reference Salmon and Lass1999: 48), who did not accept it as a marker of possession until the early seventeenth century. Grammarians were then compelled to accept the prevailing trend and ‘the handbooks of usage were obliged to acknowledge the inevitability of linguistic change and the facts of usage’ (Beal Reference Beal, van Ostade and van der Wurff2010b: 40).

References to the origin and development of the apostrophe in English are scarce in the relevant literature, the bulk of them published in the last century and mostly concerned with the spread of the possessive apostrophe. It is, in our opinion, a desideratum to account for the uses of this symbol in the expression of the past tense of regular verbs or the plural nominative, where the apostrophe functioned as an orthographic mark. More importantly, studies of the apostrophe using a corpus-based framework are still lacking, and these could potentially confirm the period in which the different apostrophes developed and perhaps the circumstances behind this development. In light of this, the present article investigates the standardisation of the apostrophe in the English orthographic system in the period 1600–1900 and pursues the following objectives: (a) to study the use and omission of the apostrophe in the expression of the past tense, the genitive case and the nominative plural in the period; (b) to assess the relationship between the three uses and their likely connections; and (c) to evaluate the likely participation of grammarians in the adoption and the rejection of each of these phenomena in English.

2 Methodology

The source of data for this analysis is A Representative Corpus of Historical English Registers (ARCHER 3.2, Denison & Yáñez-Bouza Reference Denison and Yáñez-Bouza2013), ‘a multi-genre historical corpus of [3.3] million words of British and American English covering the period 1600–1999’ (Yáñez-Bouza Reference Yáñez-Bouza2011: 205). It represents a wide range of register diversity that encompasses material from twelve different text types, including printed texts, such as fiction prose, popular and specialist exposition and scientific prose, and handwritten documents sampling personal styles of communication (Yáñez-Bouza Reference Yáñez-Bouza2011: 207).Footnote 5

On methodological grounds, the process of extracting the data was not straightforward in view of the particularities of ARCHER. Even though this corpus is offered in both plain text and tagged formats, the former was chosen as the ideal input for the feature under investigation. The tagged version of the corpus is also modernised, hence the risk of losing some of the uses of the apostrophe, especially those concerned with the expression of the regular past tense or the nominative plural.Footnote 6 This significantly complicated the task of data retrieval in view of the absence of an umbrella string for the generation of the complete set of instances. The occurrences of the apostrophe in the regular past tense, on the one hand, were generated with the strings *’d and *ed for the cases with and without the apostrophe, respectively, thus providing the complete set of instances with both regular and irregular forms, spellings with -y included. The possessive apostrophe, on the other hand, was searched for with the prompts *'s, *s’ and *s for the generation of all the instances with and without this symbol. Finally, the occurrences of the nominative plural were also gathered with the string *'s. This process is not free of noise and some time-consuming disambiguation was required to select the appropriate input in view of context.Footnote 7 All in all, the present study eventually analysed a total of 166,550 instances from ARCHER, of which 74,117 appear in the regular past tense (4,358 with and 69,759 without the apostrophe), 8,408 instances in the possessive case (7,317 with and 1,090 without the apostrophe, respectively) and 84,025 instances with the plural nominative (40 with and 83,985 without the apostrophe). For the purpose of comparing their frequencies over time and across genres, these were normalised to a common base of 10,000 words.

Additionally, the Early English Books Online corpus (EEBO) has been used to investigate the early uses of the possessive apostrophe in the late sixteenth century. With 755 million words, EEBO consists of over 25,000 texts printed in the period 1475–1700, organised into decades. Its POS-tagging facilitated searching for instances of the genitive, since the string ?*_GE not only retrieved the tokens of -'s, but also inflected nouns like christes and lordes. In total, 836,805 instances of the genitive were gathered from this corpus, 589,995 with and 246,810 without the apostrophe. In view of their greater raw frequencies and of the greater size of EEBO, these results were normalised to a common base of 100,000 words.Footnote 8

3 Analysis

This section addresses the origin and development of the different uses of the apostrophe in the period 1600–1900 when this symbol is found to have both its most widespread diffusion in quantitative terms and its most varied number of uses in qualitative terms. The article is concerned with the three most common uses of the symbol in the period, that is, (a) the expression of the regular past tense where variation is found in the forms -’d and -ed; (b) the formation of the possessive case both with and without the apostrophe; and (c) the so-called greengrocer's apostrophe, where the nominative plural appears with and without the symbol.

3.1 The apostrophe in the regular past tense

The adoption of the apostrophe in the inflectional morpheme -ed, as found in the past tense and past participle forms of weak verbs, had a phonological rationale. According to Görlach (Reference Görlach1991: 58), the symbol would be used in those items where pronunciation was not syllabic, but consonantal, such as lov'd. This suggests that the apostrophe would not occur in the past forms of verbs with infinitives ending in -t and -d, such as want and need, since the graph that it omits would be phonologically realised as the syllable /ɪd/. This assumption is corroborated in ARCHER, where there are only six tokens of the like, such as relat'd, dissapoint'd and spirit'd. In the light of the unavailability of the apostrophe in these contexts, these verbs have been excluded from the study altogether. Other than -ed and -’d, the analysis examines the selection of -t and -’t, not only due to their concurrence during the Early Modern English period (Osselton Reference Osselton, Blake and Jones1984: 133‒4; Cook Reference Cook2004: 171‒2), but also to their combination with the apostrophe.

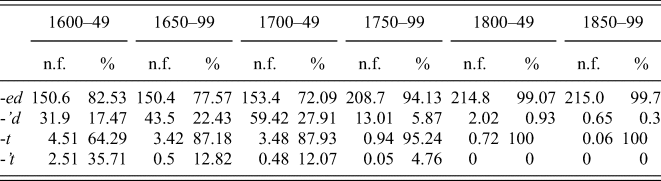

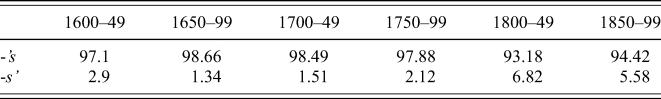

Table 1 presents the distribution of -ed versus -’d over time, on the one hand, and of -t vs -’t, on the other. Overall, the percentages show that the full forms ‒ i.e. the variants without apostrophe ‒ are consistently more frequent than their counterparts.Footnote 9 From the mid eighteenth century onwards, the former occur in roughly 95 per cent of the tokens of the past morpheme, leaving the use of the apostrophe in a marginal position. Though these trends in usage seem relevant in understanding the process of standardisation, the normalised frequencies shed yet more light on the orthographic configuration of the morpheme. The variant -ed is, by far, the topmost frequent rendering of the past from the onset of the period and it is followed, at a distance, by the abbreviated form, -’d. In the meantime, -t and -’t are sporadically used, especially since their selection is dependent on the phonological features of the verb in question and is not always systematic. If the infinitive ends with a voiceless consonant, the morpheme is realised as /t/, as in published, and its orthography might as well reflect this sound. However, this criterion is not consistently fulfilled and, as reflected in the data, most verbs are spelled -(’)d by default.Footnote 10 Moreover, the forms -t and -’t start declining in the seventeenth century and virtually disappear by the nineteenth, a development that Cook (Reference Cook2004: 172) has already traced in drama.

Table 1. The variants -ed, -’d, -t and -’t in the expression of the past over time

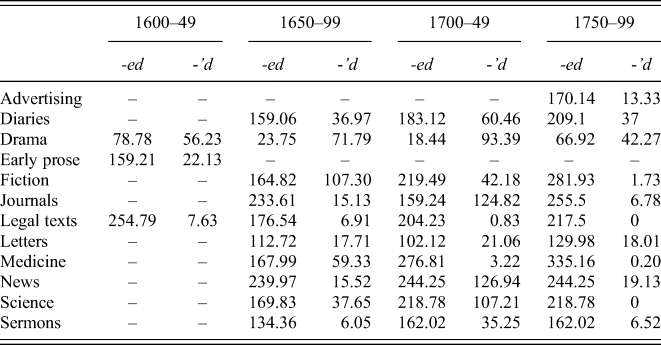

More compelling in the present discussion is the distribution of -ed and -’d over time. Although the overall dominance of -ed has already been elucidated in table 1, figure 1 best depicts the ups and downs in the development of these orthographic variants. The figure shows that, despite the overall stability of -ed in the first half of the period, -’d had nearly doubled in frequency in the first half of the eighteenth century. Nevertheless, the apostrophe would quickly lose ground during the next fifty years, presumably dropping to pre-1600s levels. In the meantime, the full form underwent an increase in frequency diametrically opposed to the loss of -’d, the patterns in the figure diverging from each other in a parallel fashion. The nineteenth century witnesses, once again, the stabilisation of -ed, with slight increases throughout, whereas its counterpart continues declining and nearly becomes extinct. The figure also points to the apparent correlation between the decline of -’d and the rise of -ed, since it seems as if the spelling variants were in complementary distribution. Nonetheless, the qualitative analysis of the data shows that the preference for -’d does not correspond to any sort of selectional criterion: the topmost frequent fifty verbs partaking of the apostrophe are not only spelled with -ed as well, but they are also more frequent in the latter case. This demonstrates that both -ed and -’d shared an ecological niche and that the only issue preventing linguistic competition was the very incidence of the full form in the expression of the inflectional morpheme.

Figure 1. Distribution of -ed and -’d in the expression of the past over time (n.f.)

Genre variation has often been considered a decisive factor in the selection of the apostrophe in the regular past (see Görlach Reference Görlach1991; Cook Reference Cook2004; Tieken-Boon van Ostade Reference Tieken-Boon van Ostade and Mugglestone2006; Moore Reference Moore2012). In its most elementary function, as in the case at hand, the apostrophe was ‘purely phonetic [in] marking the omission of a sound, and [it] was therefore frequently used in drama texts’ (Görlach Reference Görlach1991: 58), written to be recited. Similar assertions have been made about other text-types closely related to speech, such as poetry (Moore Reference Moore2012: 800) and private writing, where -’d is said to have ‘lingered much longer’ (Tieken-Boon van Ostade Reference Tieken-Boon van Ostade and Mugglestone2006: 256).Footnote 11 Table 2 presents the distribution of the apostrophe across genres in the seventeenth and the eighteenth centuries to show whether, at least in the period when this type of apostrophe reached its peak, this symbol was more prone to occur in speech-based text types. Interestingly enough, the period 1600–49 sees the rise and development of this kind of apostrophe in English writings and, already at this incipient stage, it amounts to 56.23 occurrences in drama in sharp contrast with the other text types represented early on in the corpus, where it is negligible. The period 1650–99, on the other hand, confirms this same tendency where dramatic texts again reach the highest distribution with 71.79 occurrences, with the exception of fiction, which amounts to 107.3 occurrences.Footnote 12 It is significant to note that the phenomenon also spreads to other genres like medicine and science and, to a lesser extent, to letters and news. This use of the apostrophe reaches its zenith in the first half of the eighteenth century, when it is also frequent in drama along with other genres such as news (126.94 occurrences), journals (124.82 occurrences) and science (107.21 occurrences), a fact which confirms the diffusion of the phenomenon across the different text types. The period 1750–99, however, shows the systematic decline of this use of the apostrophe across all genres with the exception of drama, where it is found to be frequent, with 42.27 occurrences.

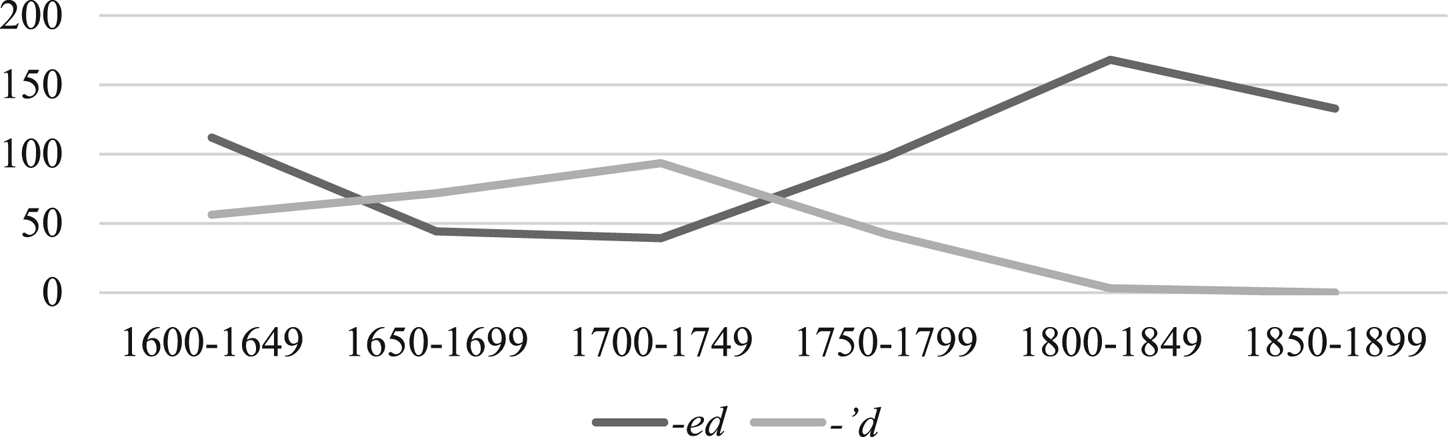

Table 2. The apostrophe in the past tense across genres (n.f.)

Drama, as shown, stands out as the only genre where the apostrophe is found to have a consistent distribution over time, with a significant role since the seventeenth century. Figure 2 presents the classification of the regular past tense forms in the dramatic texts of the corpus both with and without the apostrophe to discern if there was any actual competition with the full suffixed form -ed. The form -’d, on the one hand, has a growing diffusion until reaching its climax at the end of the seventeenth century and, more importantly, it comes to outnumber the full suffixed form -ed in the period 1650–99, perhaps as the immediate result of the phonetic virtues of this symbol in particular environments. The period 1700–49, however, marks the progressive decline of the apostrophe in these texts to the extent that it becomes practically negligible towards the end of the century. This change of attitude was likely to have been the result of the eventual standardisation of the suffixed form at the turn of the century.

Figure 2. Distribution of -ed and -’d in dramatic texts over time (n.f.)

The frequency of the regular past tense apostrophe in those genres written to be read aloud suggests that its phonological rationale ‒ i.e. marking consonantal pronunciation, instead of syllabic ‒ must have been evident among language users. However, this function was never overtly codified, since grammarians seemed to systematically disregard this use of the apostrophe. More particularly, instances of -’d are only ever found in Jonson's and Baker's works, the former including this variant among other ways to shorten conjugated verbs (Waite Reference Waite1909: 94), the latter criticising the practice of eliminating one of the geminate consonants in verbs like stunned – stun'd (Baker Reference Baker1770: 26-7). Nevertheless, these authors never assess the propriety of the construction and neither do others like Lowth (Reference Lowth1763) or Ash (Reference Ash1791). Although this lack of prescription may be understood as implicit acceptance, the apostrophe virtually disappeared in this domain during the nineteenth century, with grammarians doing nothing to either encourage or discourage this development. Instead, the standardisation of -ed seems to have been almost unanimously endorsed by eighteenth-century printers as a whole, a practice that the data in table 2 confirmed. By the end of the eighteenth century, the genres with a higher incidence of -’d were diaries, news and letters, while this variant had virtually disappeared in most of printing.

3.2 The apostrophe in the possessive case

In the synthetic expression of possession, the apostrophe seems to entail the omission of linguistic material. Whereas -'s was formerly believed by some scholars to be an abbreviation of the phrase the boy his car (see Sklar Reference Sklar1976: 178), it is more likely a relic of the case system, a remnant of the genitive inflectional morpheme which, in Old and early Middle English, was realised as -es in masculine and neuter strong nouns, spreading later to all nominals (Mossé Reference Mossé1952: 48‒9; Nevalainen Reference Nevalainen2006: 75). Analogously to the past tense, the apostrophe in the Saxon genitive marks the historical elision of <e>, which in most cases was no longer pronounced. As in present-day English, inflectional -s and -'s only produced the syllabic pronounciation /ɪz/ if appended to word-final sibilants, as in the houses or the mouse's tail. Strang (Reference Strang1970: 109‒10) highlights that, phonologically, the distinction between nominative and genitive singular and plural nouns is realised in a ‘two-term system of contrast’, whereas in writing the system is made up of four terms. On the one hand, nominative singulars remain unmarked while nominative plurals and genitives are systematically marked with a sibilant in speech. On the other hand, whereas nominatives have no apostrophes whatsoever in standard written English, the position of this symbol varies in genitive singulars, the boy's car, and in genitive plurals, the boys’ car. Today, the sole function of the genitive apostrophe is to avoid confusion in written language. However, there is no agreement as to when it acquired such a role.

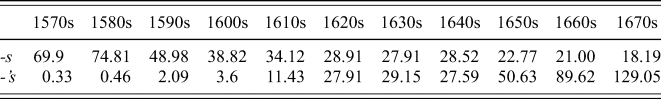

The seventeenth century was, by most accounts, crucial in the development of the phenomenon. Nevalainen (Reference Nevalainen2006: 74) argues that the apostrophe was introduced in the late 1600s, whereas Görlach (Reference Görlach1991: 58‒9) and Cowie (Reference Cowie2012: 604) claim that by that time the symbol was already widespread and even obligatory. Due to such lack of consensus and for the purpose of outlining the timeline of the possessive apostrophe, table 3 presents the frequencies of -'s and -(e)s for the period 1570–1670 in EEBO. The data show that the forms compete against each other between 1620 and 1640, until the apostrophe becomes dominant in the 1650s and continues growing thereafter. The data in ARCHER, as illustrated in figure 3, also reflect the early development on the part of the genitive apostrophe, in the period 1600–49. Although the structure seems to decrease in frequency throughout the seventeenth century, the -'s continues to be dominant and, soon after, it starts gaining ground at the expense of its counterpart, which dropped sharply and had virtually disappeared by the nineteenth century.

Table 3. The forms -(e)s and -'s in the expression of the genitive over time

Figure 3. Distribution of -(e)s and -'s over time (n.f.)

Despite the early occurrences, the possessive apostrophe can be said to have been introduced into the language more systematically during the late sixteenth century. After a short-lived period of competition, -'s became the dominant form in the 1650s and, in the light of its expansion, it might have been considered standard ‒ or obligatory ‒ by the first half of the eighteenth century. The apostrophe thus seems to have become the marker of the genitive case earlier than most scholarly accounts reckoned, especially when considering the data from a qualitative stance. Indeed, as already mentioned, the genitive singular and the genitive plural have typically been discussed separately, with the latter having undergone standardisation at a later time, namely, the late eighteenth century (Görlach Reference Görlach1991: 58‒9; Cowie Reference Cowie2012: 604). It is highly likely that plural genitives were not as quick to regularise due to their lower incidence in use. Comparing the occurrence of -'s and -s’, as in table 4, proves that the latter amount to a very marginal proportion of all the genitives analysed, representing at best 6.82 per cent of the tokens in the nineteenth century, i.e. only after this form had presumably undergone standardisation.

Table 4. The singular (-'s) and plural (-s’) forms of the Saxon genitive (%)

Regardless of the diffusion and standardisation of the genitive apostrophe over time, prescriptivist grammarians still grappled with the uses of this symbol. In his review of the English grammar tradition, Leonard (Reference Leonard1962: 193‒4) argues that the apostrophe was not very frequently mentioned nor employed in the seventeenth century, whereas it seems to have been ‘fairly well-established in the course of the eighteenth’. Although in his 1640 grammar Jonson (Waite Reference Waite1909: 86) does not include it among his paradigms, where there is syncretism between the nominative plural and the genitive forms, Lowth (Reference Lowth1763: 26) and Ash (Reference Ash1791: 30) discuss the apostrophe as conventional usage though still highlighting its inadequacy in examples such as Thomas's book and fox's, where the elision is orthographic but not phonological.Footnote 13 The disapproval of the apostrophe, however, is yet more fervent in the plural. Over time, grammarians put forward a number of proposals for the expression of the plural genitive, which included syntactic and orthographic changes, such as discarding the synthetic structure in favour of the of-phrases, as in house of lords instead of lords’ house (Johnson 1755: n.p., as cited in Leonard Reference Leonard1962: 195) and cutting off one of the inflectional -s terminations (Greenwood Reference Greenwood1753: 65) or reversing the apostrophe as in the warrior‘s arms (Buchanan Reference Buchanan1767: 124‒5). The latter, though closer to the contemporary configuration, were criticised on the grounds of their ‘stiffness and formality’, since they might be ‘of service to the reader only, and not the hearer’ (Mennye Reference Mennye1785: 76). Nevertheless, all this confusion and controversy did not stem from actual usage. Priestly (Reference Priestly1769: 7), who has been described as ‘the most … consistent follower of usage in this period’ (Leonard Reference Leonard1962: 315), briefly explains that plural genitives are expressed by simply adding the apostrophe, as in Stationers’ arms, thereby settling the matter. In any event, the grammarians’ disagreement over the use of the apostrophe, along with the data discussed above, ultimately confirm that these linguistic commentaries had no impact on the language whatsoever.

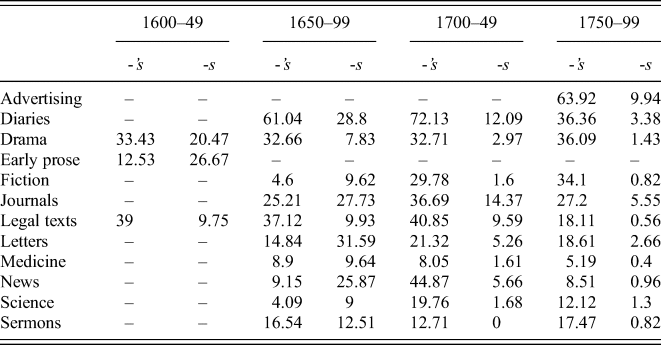

For the purpose of ascertaining the potential impact of genre variation in the diffusion of the genitive apostrophe, table 5 represents the distribution of the possessive case both with and without the symbol across text types in the period 1600–1799. As shown, the general tendency is the systematic adoption of the apostrophe across all genres in all the subperiods, even though the presence of the -s inflection in the period 1650–99 is still found to outnumber the apostrophe in formal writing, such as news (25.87 vs 9.15 occurrences) and, to a lesser extent, journal writing (27.73 vs 25.21 occurrences) and science (9 vs 4.09 occurrences). The adoption of the apostrophe, therefore, is more reluctant in this type of formal and academic writing than in all the other genres. Although the rendering -'s is, interestingly enough, also widespread in the case of diaries in the period 1650–99 (31.59 vs 14.84 instances), which might have been influenced by the conventions of printing at the time, letters, also representative of handwriting, did not exhibit this until the first half of the eighteenth century (21.32 vs 5.26 instances).

Table 5. The apostrophe in the possessive case across genres (n.f.)

On another note, drama is again of special interest since the apostrophe prevails over the inflected form from the first subperiod (with 33.43 and 20.47 instances, respectively). The early dissemination of the apostrophe in dramatic texts is again connected with its potential to mark the omission of a sound and, therefore, more likely to appear in those texts written to be recited. Similarly, the spread of -'s is also notable in legal texts from the onset of the seventeenth century; these texts were presented to the court for its consideration and their implicit orality stems from the fact that they were in principle written to be read aloud as well. After these subtle differences in the expression of the possessive case in the seventeenth century, the period 1700–49 definitely marks the systematic diffusion of the apostrophe, which thus predominates over the inflected form across all genres.

3.3 The apostrophe in the nominative plural

This is, in our opinion, the most peculiar deployment of the symbol in the history of English writing. In itself, it is not a symbol specifying a grammatical, semantic or pragmatic function, but a practice which at some point plural nouns undertook for visual purposes. The apostrophe in these environments is often referred to as the greengrocer's apostrophe, defined as the placing of an apostrophe before the terminal -s of a nominative plural noun (OED s.v. greengrocer's apostrophe n.), regardless of whether the noun ends with a vowel as in orange's, or a consonant as in doctor's. Some grammarians have claimed that this is the result of lack of education, where writers tend to hypercorrect in those contexts considered to be ‘too abrupt’, as in pie's rather than the correct plural form pies along with numerals such as 1970's, the letters of the alphabet like three A's, and other odd spellings like do's and dont's (Hook Reference Hook1999: 45‒6). Oddly enough, this use of the apostrophe does not share any connection with its original use, elsewhere conceived to mark omitted letters. In this very case, however, there is no <e> to omit in the expression of the plural,Footnote 14 being instead a redundant symbol reduplicating the function already expressed by the plural morpheme.

The greengrocer's apostrophe dates back to the seventeenth century; it was initially more likely to occur after vowels and later after consonants as well (Cook Reference Cook2004: 94). Table 6 reproduces the occurrence of the plural morpheme both with and without the apostrophe in the corpus where it is shown that this use of the symbol was negligible in the history of English. It is found to reach 1.37 occurrences in the period 1600–49 and since then it has decreased to such an extent that it becomes practically non-existent throughout the nineteenth century, perhaps as a result of the grammarians’ proscriptive pronouncements (Alford Reference Alford1864: 21; Beal Reference Beal2010a: 59). This practice was surely the result of the impulse of some seventeenth-century printing houses and, unlike the previous uses of the apostrophe, it did not diffuse perhaps on the assumption that it did not have a particular clarifying function and could be easily left out, hence the overwhelming preference for the historical morpheme -s.

Table 6. The plural nominative -s and -'s (n.f.)

In view of the low frequency of this symbol from a historical perspective and the grammarians’ proscribing attitudes, one cannot but wonder why it gained such a prominent role throughout the twentieth century. The issue, according to Hook, is not a matter of pronunciation but rather one of representing speech through pronunciation, especially for those writers without an education in English grammar and spelling. On the one hand, it is the result of the interference in those plurals which end in an -s, where the average writer of English does not see the wood for the trees when differenting the boxes and the boxe's or even in family identifications such as the Jones, the Jone's, the Jones’, the Jones's or the Joneses’. At other times, on the other hand, the issue stems from the ‘misstimuli due to frequent examples of errors in the various print media’, which spread the generalisation and socialisation of particular writing conventions like the one at hand (Hook Reference Hook1999: 49). This use of the apostrophe is a rara avis today and the sporadic cases are limited to commercial purposes rather than the true survival of the nominative plural form, which did not require any type of case marking besides the -s termination. As far as the genitive was concerned, however, the apostrophe was required as a marker to differentiate it from plural nominatives.

3.4 Concluding remarks

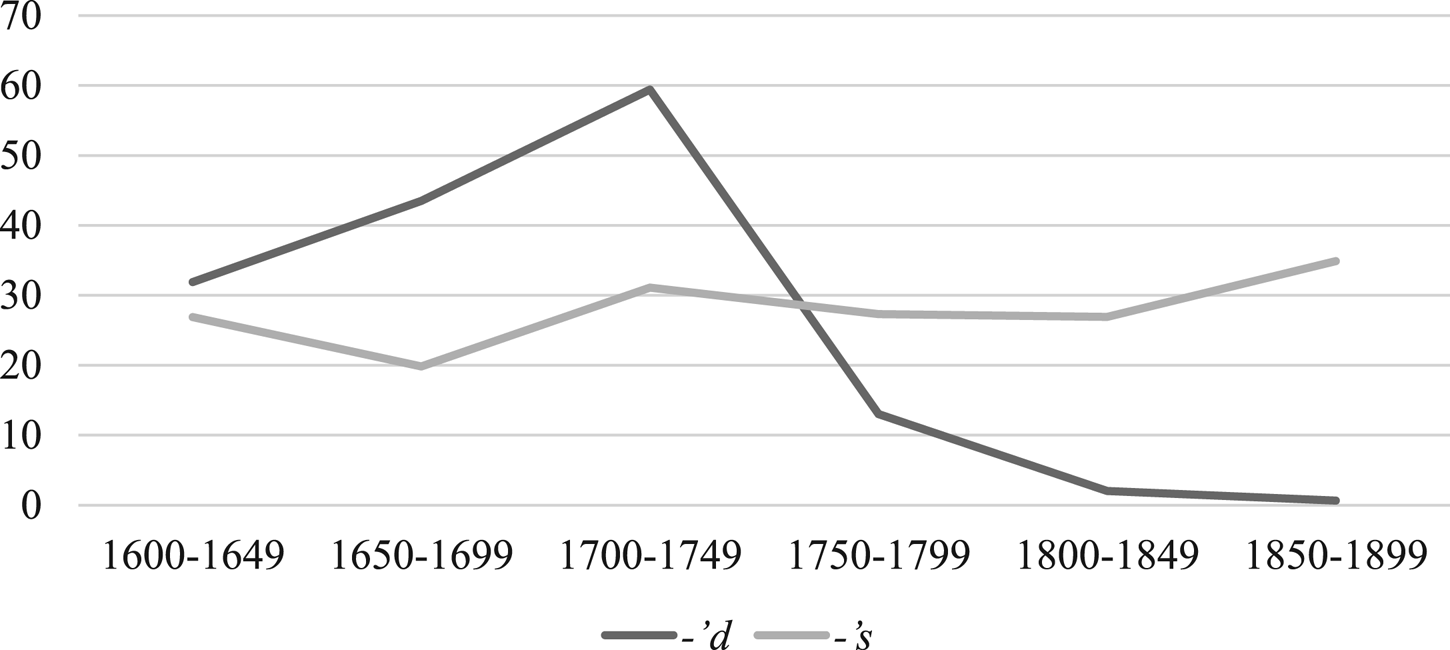

The apostrophe has been described as a printer's mark especially designed ‘for the eye rather than for the ear’ (Sklar Reference Sklar1976: 175; Little Reference Little1986: 15). Though the symbol was rationalised as marking a phonological elision, its functions in the past and genitive inflections became purely orthographic: the apostrophe simply highlighted the omission of the graph <e> in the morphemes -ed and -es, where the pronunciation of the vowel would only be prompted under particular phonological circumstances. Despite their functional similarities, -’d and -'s had entirely different outcomes in standard English, as discussed above and also illustrated in figure 4. Although the apostrophe was far more frequent in the expression of the past than of the genitive until the first half of the eighteenth century, the former dropped just as the latter was extending across text types and entered standard usage. This turn of events thus raises questions regarding the standardisation of the apostrophe: what led to the rise of -'s and to the decline of -’d? Is there correlation between the two phenomena?

Figure 4. Distribution of the past (-’d) and genitive (-'s) apostrophes over time

The decrease of the apostrophe in the expression of the past tense seems to have been motivated by its own superfluity. The decline of -’d must have run parallel to that of -t and -’t: other than the surplus of forms performing one single function, the frequency of -’d was simply lower and its distributional niche more specific than those of its counterpart -ed, and thus this variant was discarded from usage. This outcome is worth considering against the backdrop of the English writing system, which, despite being sound-based, also exhibits some morphological or morphemic representations. This implies that morphemes with different phonological realisations always have the same spelling, as in the regular past tense -ed or the plural number -s (Cook Reference Cook2004: 18, 75). Conversely, it was the redundant nature of the apostrophe which secured its standardisation in the Saxon genitive. Although the symbol had once stood as an abbreviation for -es, the full form was long forgotten among contemporary speakers, with the apostrophe standing as a vestige of the past (Sklar Reference Sklar1976: 175‒6). However, there was much confusion and a pressing need for disambiguation in nouns ending in -s, since it was often unclear whether the inflection corresponded to the nominative plural or the genitive case, regardless of number. The apostrophe thus became the signpost of the genitive, spelled -'s for the singular and -s’ for the plural.

In themselves, linguistic changes unfolding in the Early and Late Modern English periods often bring to the fore the roles possibly played by either grammarians or printers. The first took upon themselves the fixing of the language and a myriad of grammars were published from the mid eighteenth century onwards. Their timing, however, poses a problem in the present discussion: by the time the grammar-writing tradition became prominent in England, the apostrophe was headed well into extinction in the past tense and into standardisation in the genitive case. The discussion in sections 3.1. and 3.2. illustrated that, though grammarians did still engage with the regularisation of this symbol in the possessive (see section 3.2.), they ignored the construction -’d, perhaps because its decline preceded their endeavours. At any rate, the efforts of these prescriptivists regarding the uses of the apostrophe are best summarised by Leonard (Reference Leonard1962: 197), who claims that ‘[e]ighteenth-century grammarians introduced confusion into usage, and … usage in spite of them settled the matter quietly as it had formerly stood’. The lack of involvement on the part of grammarians, despite overtly commenting on the language, suggests instead a role for the other potential actors of change: printers.

The printers’ influence on the standardisation of orthography was, if anything, indirect. As part of their tasks, correctors, typesetters and printers would tweak the spellings of the manuscript, either to accommodate the text to external needs (Scragg Reference Scragg1974: 72) or to follow specific in-house guidelines (Tyrkkö Reference Tyrkkö2013: 152). Although the mid sixteenth century saw the formation of a printers’ guild (Rutkowska Reference Rutkowska2013: 125‒6), there is no material evidence to corroborate the collaboration between members of the trade: there are no stylesheets or any other usage guidelines pointing towards a joint endeavour (Brengelman Reference Brengelman1980: 333). Nonetheless, recent studies have confirmed that printers did perform as a community of practice in the promotion of certain orthographic forms that eventually became standard (Rutkowska Reference Rutkowska2013: 142; Tyrkkö Reference Tyrkkö2013: 169). It seems plausible that the apostrophe should have been standardised as the product of such communal practices. Interestingly enough, while grammarians were more concerned with the cases of elision of the apostrophe, our data suggest that it was printers who again pioneered and disseminated the use of this symbol for the expression of the singular possessive case in the seventeenth century, which the grammarians would accept in the course of the eighteenth century (Salmon Reference Salmon and Lass1999: 48).

The functions performed by the apostrophe thus coincide with the self-appointed objectives of the early printers. According to Moxon (1638: 220, as cited in Tyrkkö Reference Tyrkkö2013: 157), ‘A good Compositer is ambitious as well to make the meaning of his Author intelligent to the Reader, as to make his Work shew graceful to the Eye, and pleasant in Reading’ and the apostrophe might have been initially introduced in English for the purpose of maintaining these pretensions. In the first place, -’d and -'s were aids for reading out loud, especially fitting in dramatic texts. Though the apostrophe remained relevant in the genitive over time, -’d became superfluous. This shift, along with the appararent desire for regularisation on the part of the printers, might have triggered the extinction of this spelling variant altogether. Although the analysis in this article does not give sufficient grounds to claim that the printers’ community of practice led to its standardisation, the data are open to this interpretation. After all, the apostrophe was diffused in printed texts like drama, law and prose fiction, while handwritten genres like letter-writing jumped on the bandwagon at different points in time. There is, then, correlation inasmuch as the promotion of -'s had the same rationale as the disappearance of -’d.

4 Conclusions

Although the systematic adoption of the apostrophe in the repertoire of English punctuation is a late sixteenth-century development, the symbol quickly gained ground and acquired a variety of functions that included, but were not limited to, the past tense (-’d), the genitive case (-'s) and the nominative plural (-'s). In terms of usage, this article has shown that, whereas the so-called greengrocer's apostrophe remained sporadic throughout the period, the first two were substantially employed. More particularly, this study has outlined the functions performed by -’d over time as well as the standardisation process undergone by -'s. On the one hand, the apostrophe seemed to perform a phonological function in the expression of the past tense, later rendered superfluous and ultimately triggering its downfall. On the other hand, the data have proved that the possessive apostrophe was introduced earlier than accounted for in the literature, and had thus spread and overcome its counterpart by the early eighteenth century. In discussing language usage, we must acknowledge the role possibly played by the printers, by means of a community of practice, towards shaping what became the standard. The question ‘whose language are we looking at’ has a very straightforward answer (Tyrkkö Reference Tyrkkö2013: 152). Indeed, the configuration that we know today ‒ whether through overt codification or not ‒ comes directly from these printers. The apostrophe thus seemed to have its origins in print, which also diffused the norm of correctness affecting either its promotion or its decline.

When it comes to prescriptivism itself, we must necessarily question the actual validity of its prerogatives in the orthography of English as we know it today. The grammarians’ precepts were in most cases the result of their own dissatisfaction with, in Robert Lowth's terms, the ‘false syntax’ of English (Fries Reference Fries1927: 32; Yáñez-Bouza Reference Yáñez-Bouza2015: 72) and therefore proposed a new grammar based on their ideal of language, mostly utopian, stemming from their knowledge of Latin. The apostrophe is a typical case in point as an issue significantly ignored in seventeenth-century grammars and usage books while misinterpreted one century later as the bulk of them were unable to propose an unambiguous practice in the three contexts under discussion. Curiously enough, however, some of these precepts became dogmatic for the upcoming generations to the extent that these grammars were used as compulsory textbooks in English primary and secondary education until the twentieth century. Notwithstanding this, these tenets never managed to take shape in actual English usage in view of the fact that the latter is in itself the one shaping the norm, and not the other way round (Leonard Reference Leonard1962: 197).

In light of the different uses of the apostrophe after its inception in the Early Modern English period, either orthographic in the expression of the genitive singular or phonological in the regular past tense, it became in itself a symbol expressing ‘an incomplete string that [had] to be completed by the reader’ (Kirchhoff & Primus Reference Kirchhoff, Primus, Cook and Ryan2016: 106). Some sort of order was necessary out of the apparent chaos of the manifold uses and functions of the apostrophe and, according to Gause's principle of competitive exclusion (Gause Reference Gause1934: 47; Aronoff Reference Aronoff, Reiner, Gardani, Dressler and Luschützky2019: 41), the form considered to be more efficient reproduces at a higher rate than the less efficient form, which is often bound to extinction. Printers presumably selected the most clarifying use of the apostrophe while the other was necessarily compelled to displacement and disappearance.