Introduction

The widespread use of English in advertising around the world has received considerable attention in recent decades. A number of researchers have looked at this practice in European countries such as France, Germany, Greece, and Italy (e.g. Martin, Reference Martin1998, Reference Martin2002, Reference Martin2006, Reference Martin2007, Reference Martin2008; Hilgendorf & Martin, Reference Hilgendorf, Martin and Thumboo2001; Oikonomidis, Reference Oikonomidis2003; Vettorel, Reference Vettorel2013). Other scholars have examined this phenomenon in various contexts in Asia, for instance in India, Iran, and Russia (e.g. Bhatia, Reference Bhatia1987, Reference Bhatia1992, Reference Bhatia, Kachru, Kachru and Nelson2006, Reference Bhatia2007, Reference Bhatia, Lee and Moody2012; Ustinova & Bhatia, Reference Ustinova and Bhatia2005; Bhatia & Baumgardner, Reference Bhatia, Baumgardner, Kachru, Kachru and Sridhar2008; Baumgardner & Brown, Reference Baumgardner and Brown2012). One part of the world, however, drawing relatively little scholarly attention to date has been the Maghreb region of northern Africa.

This article addresses this lack of research by exploring English use in outdoor advertising in the Kingdom of Morocco, located on Africa's northwest coast. This is to our knowledge the first study to examine such growing uses of English within the advertising domain of this Expanding Circle context, where the language historically has functioned as a foreign code used only for international interaction. As is occurring in other parts of the third sphere of Kachru's (Reference Kachru1990) Three Circles model, a shift currently seems to be underway in Morocco. In recent years, English has been gaining uses as an Additional Language, becoming part of Moroccans’ local linguistic repertoire as well.

Given Morocco's long history of multilingualism, the country presents a distinct and an intriguing case for considering English use. Moroccans already have varying degrees of proficiency in as many as four principal languages: Berber (Tamazight), Arabic, French, and Spanish (David, Simons & Fennig, Reference David, Simons and Fennig2019). Advertising copywriters, therefore, already have multiple languages to choose from in order to create compelling ads to attract consumers. In particular, the French language has played an especially important role in the country following nearly 50 years of French colonial rule in the early 20th century. The growing uses of English within this context, therefore, take on an added, more complicated significance not commonly found in other parts of the Expanding Circle.

Our focus here is on English use in commercial outdoor advertisements, which are viewed outside the home as people go about their daily activities. In spite of the conspicuous growth in online advertising over the last decade, outdoor advertising remains widespread throughout urban and rural communities around the world. In the context of India, for example, Bhatia (Reference Bhatia, Lee and Moody2012; see also Bhatia & Bhargava, Reference Bhatia and Bhargava2008) identifies numerous types of surfaces commonly used for promoting products and services. These include billboards, wallscapes, storefront signage, bus panels and shelters, school programs, writing instruments such as pencils, as well as bus and train tickets. Bhatia (Reference Bhatia, Lee and Moody2012: 233) considers such advertising to be ‘non-conventional’, as compared to more ‘conventional’ forms diffused through television, radio, print, and Internet-based media. The ubiquity of outdoor ads reflects their relative affordability, as they enable advertisers to reach the greatest number of people at the lowest cost (Williams, Reference Williamsn.d.)

Outdoor advertising furthermore is intriguing for the broader, general impact it has within a community. More conventional ads found in magazines, newspapers, social media websites and apps generally are seen by a relatively targeted demographic. Only those individuals who purchase particular materials or consult certain online platforms are exposed to them. Outdoor advertisements, in contrast, are immediately visible to all people living in a community, and therefore reach a broader spectrum of the general public. As such, they better reflect the general role English plays on a macrosociolinguistic level within a society.

The following qualitative analysis focuses on a randomly selected sample of nine outdoor advertisements that were displayed in the Moroccan city of Casablanca between June and September of 2014. They fall into two main linguistic categories: partly in English (code-mixed) and completely in English (monolingual). The ads include four posters, three wallscapes, one bulletin, and one storefront signage. Poster advertisements generally appear on major avenues and in commercial shopping districts, where they target pedestrians and people in automobiles (Out of Home Advertising Association of America [OAAA], 2019b). Wallscapes, also known as wall murals, are advertisements that cover the surfaces of buildings. Bulletins, ‘the largest and among the most impactful standard-sized OOH [out of home] media formats’, appear alongside highways and arterial roads (OAAA, 2019a). Storefront signage, as the name indicates, are placed at the entrance of shops. The nine advertisements examined in this study market products from various retail sectors: real estate, automobiles, apparel, and home furnishings.

Before proceeding to the analysis, a brief sociolinguistic profile of Morocco provides background information for better understanding the significance of English use in the country at present.

Sociolinguistic profile of Morocco

Morocco's population of nearly 34 million people participates in maintaining an interesting linguistic tapestry (Haut-Commissariat au Plan, 2015). Aside from mono- and multilingual speakers of the country's four major languages, the population also has large segments that speak distinct varieties of Arabic and Tamazight.Footnote 1 In spite of this already rich constellation of numerous indigenous varieties and former colonial languages, English now is emerging as a fifth code of use.

The history of contact with foreign speech communities in Morocco is long, dating back some 3,000 years. Through the first millennium, initially the Phoenicians (Ennaji, Reference Ennaji2005: 26) followed by the Carthagians, Romans, Byzantines, and Vandals (Sadiqi, Reference Sadiqi1997: 8–9; Ennaji, Reference Ennaji2005: 9) all came to the region. The most lasting linguistic impact occurred in the year AD 682, when the Arabs conquered the territory (Alalou, Reference Alalou2018: 3). In the 1400s, the Portuguese were the first modern Europeans to invade the country, settling primarily in cities along the coast. Following Portugal's withdrawal in 1860, Spain colonized the northern and southern regions; to this day two cities on the north coast, Ceuta and Melilla, remain under Spanish rule (Ennaji, Reference Ennaji2005: 12). France colonized Morocco from 1912 to 1956, under what it called a ‘mission civilisatrice’ (‘civilizing mission’) (Ennaji, Reference Ennaji2005: 13). The policy's stated objectives were threefold: to help develop Morocco and the Maghreb region; to spread the French language and culture; and to ‘protect the French interests in the area’ (Ennaji, Reference Ennaji2005: 13). Scholars have provided alternative assessments of this period, stating more bluntly that the French ‘came to the region for commercial goals … aided by the military’ (Rosenhouse, Reference Rosenhouse, Bhatia and Ritchie2013: 900).

Once Morocco became a French Protectorate in 1912, the French language immediately became the country's sole official language (Ennaji, Reference Ennaji2005: 97) in most formal domains. These included education, government affairs (Buckner, Reference Buckner, Al–Issa and Dahan2011: 216), science, technology, business, commerce, media (Marley, Reference Marley2004: 29; Ennaji, Reference Ennaji2005: 16), and cinema (Abbassi, Reference Abbassi1977: 28). Under colonial rule, a number of Moroccans, in particular the elites, began learning French by attending French-administered schools. Over time, as economic prosperity became tied to French proficiency (Marley, Reference Marley2004: 28–29), both the elites and the masses alike demanded more instruction in French (Knibiehler, Reference Knibiehler1994: 497; Segalla, Reference Segalla2009: 41–42, 45). By 1950, school enrollment exceeded 100,000 students, a number that would have been even higher had the French government committed more resources to educating a greater percentage of the population. World Wars I and II also disrupted educational efforts, as teachers and school staff were among those enlisted into the military to fight in Western Europe and North Africa (Segalla, Reference Segalla2009: 35, 55).

Following Morocco's independence from colonial rule in 1956, both language purists and opposition parties rallied against the continuing use of French, arguing instead for Arabic to take its place (Alalou, Reference Alalou2018: 10). The new government consequently pushed to Arabize education, which was seen as a means to strengthen Moroccan identity and consolidate Arabic use (Ennaji, Reference Ennaji2005: 15; Alalou, Reference Alalou2018: 10). The Arabization Policy of 1956 reintroduced the language to the school curriculum by mandating its use as the medium of instruction (MOI) (Redouane, Reference Redouane1998: 199). Arabic was successfully implemented in primary and secondary education, but never broadly introduced at the university level. A common explanation for this was the belief that the language did not have the established vocabulary and discourses for discussing modern technology and science (Abbassi, Reference Abbassi1977: 27; Marley, Reference Marley2004: 31). A more plausible reason is the fact that generations of university professors had been educated in French during and after colonial rule. These scholars did not have the opportunity to develop equivalent proficiency in Arabic in their particular research fields, therefore they continued to use French. In addition, through the first half of the 20th century French was still one of the world's primary languages for publishing scientific research, along with German, Russian, and English (Tsunoda, Reference Tsunoda1983; Ammon, Reference Ammon and Ammon2001: 343; Gordin, Reference Gordin2015).

After more than a half-century of Arabization in Moroccan schools (Alalou, Reference Alalou2018: 1), a new language policy recently was introduced as part of the government's Vision Stratégique de la Réforme 2015–2030 (Strategic Vision of Reform 2015–2030) (Conseil Supérieur de l'Education, de la Formation et de la Recherche Scientifique, 2015: 45–51). This broader educational initiative establishes new guidelines for local and foreign languages in schools. It calls for introducing Arabic, Tamazight, and French starting in the first year of elementary education. English is to be taught as a subject beginning in middle school, in grade nine, with plans to integrate it by the year 2025 into the fourth grade of elementary school. A third foreign language, preferably Spanish, is being introduced in the high school curriculum.

The functions of these various languages change throughout the three cycles of primary, secondary, and tertiary education. French initially is taught as a subject in primary education, but used as a MOI beginning in middle school. Once English is taught as a subject from grade four to grade nine, it will also become an additional MOI in the last three years of secondary education. As for the indigenous language of Tamazight, the reform calls for it to be used as a language of communication at all levels of education (Conseil Supérieur de l'Education, de la Formation et de la Recherche Scientifique, 2015: 47, 51).

Of the four languages that have been part of the local linguistic repertoire in Morocco for the last century, French in many respects has had premier status. Moroccans have been very attached to this former colonial code, which they have viewed as a language of prestige and openness to the world, as well as a vital means for earning a decent living. Today, French remains dominant in a variety of domains, and it continues to be the MOI in higher education. It is not uncommon for a Moroccan to know a technical term in French but not in Arabic, nor is it unusual to find Moroccans for whom French in fact is their first and primary language.

The growing role for English in Morocco's education system in the coming years, however, indicates that a change is underway. It is impossible to predict the complete scale of that change and its impact on multilingualism in Morocco. Examining some of the contemporary uses of English in the domain of commercial advertising offers insights into the nature of that change and the direction in which it is developing.

English use in advertising

English has become fashionable in advertising around the world (Amiri & Fowler, Reference Amiri and Fowler2012: 297), and there is a ‘near-universal tendency’ to use it in marketing various products (Bhatia, Reference Bhatia, Kachru, Kachru and Nelson2006: 607). Bhatia (Reference Bhatia, Kachru, Kachru and Nelson2006: 603) observes that within this commercial domain English has ‘dethroned its competitor languages, such as French and Russian, and continues to do so with more vigor and dynamics.’

Motivation in using English

The two primary motivations behind the choice to use English in advertising can be categorized as functional and economic. In advertisements, English has various functions when used in speech communities where the language is not otherwise part of the local linguistic repertoire. One such function is the authoritative voice (Piller, Reference Piller2001: 160) English has as the world's current lingua franca (Crystal, Reference Crystal2003). Given the international success and influence of many Inner Circle businesses and corporations over the last century, English has a certain socio-psychological appeal in a variety of domains. These include, for example, the entertainment industry (Hilgendorf, Reference Hilgendorf2013), sports, information technology, business, fashion, the automotive industry (Martin, Reference Martin2008: 51), and scientific research (Bhatia, Reference Bhatia1992: 201). Ruellot (Reference Ruellot2011: 7) furthermore points out that English can function as a memory trigger for potential consumers. A study by Petrof (Reference Petrof1990: 12) shows that American participants had a higher recall of advertisements that used the foreign language of French as opposed to those that were in English only. Petrof (Reference Petrof1990) additionally notes that foreign languages in general serve as an effective means for attracting the public's attention.

English also can function as a signifier of quality and reliability when used in ads (Martin, Reference Martin1998: 162). In the Democratic Republic of Congo, Kasanga (Reference Kasanga2010) found that the integration of English in French advertising had the socio-psychological effect of creating trust. Kasanga (Reference Kasanga2010: 199) reports that using English gave consumers the feeling that the products sold in shops were foreign and, therefore, of superior quality. Furthermore, English can function as an instrument for ‘identity formation’ (Piller, Reference Piller2001: 180), giving consumers a sense that the quality of a product is being transferred to them personally, as they use it. In one of her studies of advertising in the French context, Martin (Reference Martin1998: 166) found that the consumption of products that are advertised in English makes French consumers feel worthy and sophisticated.

An additional distinct function of English is found specifically in job advertisements. One study (Hilgendorf & Martin, Reference Hilgendorf, Martin and Thumboo2001) found that English can function as a filter when used to advertise employment positions in Germany. Classified ads written in English instead of German attract candidates with the desired advanced proficiency in that language, while at the same time deterring applications from those who do not have the required language skills (Hilgendorf & Martin, Reference Hilgendorf, Martin and Thumboo2001: 225).

Economic gain is an overriding motivation for advertisers in general, of course, and therefore is also an important factor in deciding to use English in ads. Bhatia (Reference Bhatia and Thumboo2001: 196) relates the personal story of visiting Mexico City with friends, where they came across a billboard written in Spanish but containing two English words. One friend asked the salesperson about the reason for using Spanish and English in the same advertisement. The salesperson answered ‘I would sell only half [of the advertised product], if I did not use English’ (Bhatia, Reference Bhatia and Thumboo2001: 196). English therefore can be instrumental in helping advertisers achieve their primary goal, namely to sell more product and thus reap greater financial benefit.

Martin's (Reference Martin2002) cline of code-mixed advertising

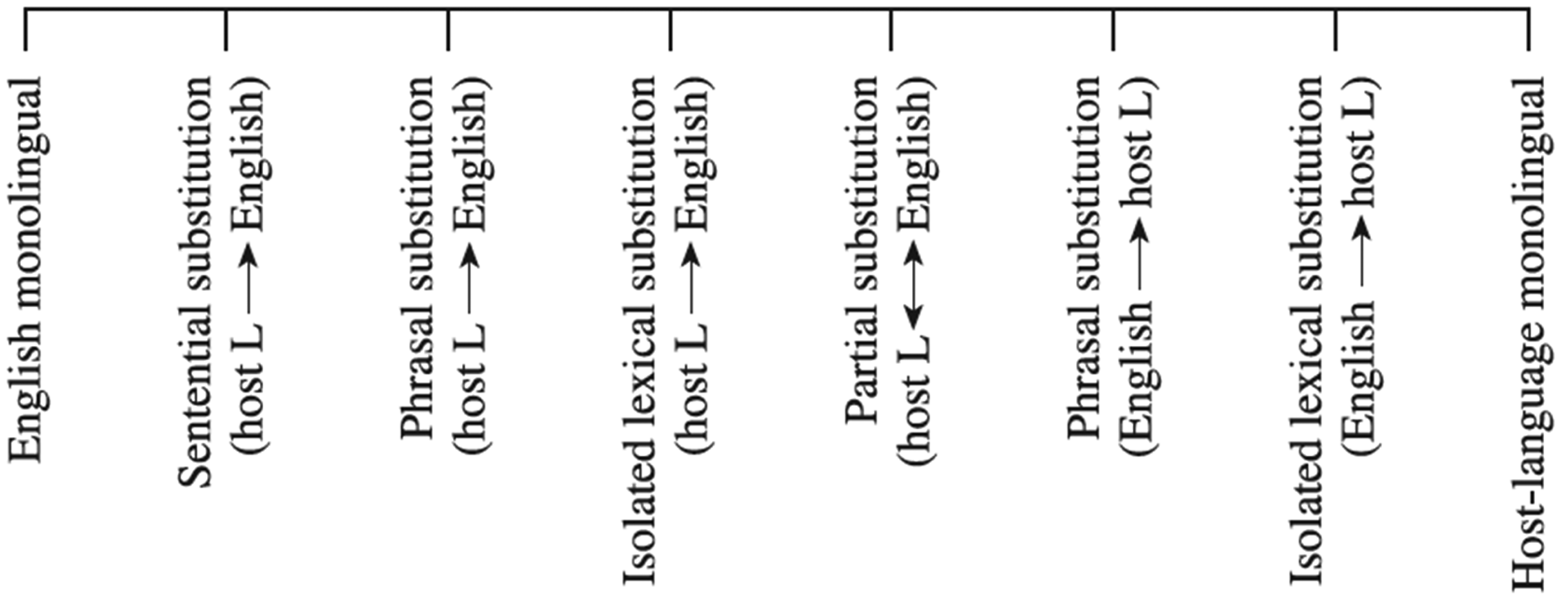

For analyzing the sample of nine code-mixed and English monolingual outdoor ads found in Casablanca, Martin's (Reference Martin2002: 385) cline of code-mixed advertising, shown in Figure 1, provides a means for categorizing the degree of English use.

Figure 1. Martin's cline of code-mixed advertising (Martin, Reference Martin2002: 385)

At the cline's right pole is the category ‘host-language monolingual,’ which refers to advertisements entirely in one of the primary languages of a given speech community. At the left pole is ‘English monolingual,’ which refers to advertisements ‘exclusively in English’ (Martin, Reference Martin2002: 387). Moving along the cline from right to left, the degree of English use therefore increases, until the ads are completely in English instead of the local language (Martin, Reference Martin2002: 385). Between these two monolingual poles are six categories along the cline.

Starting at the host-language monolingual pole, the first two categories moving to the left are isolated lexical and phrasal substitution (English → host L). These refer to ads that appear to be monolingual in the local language, but ‘actually contain English elements translated literally into the receiving language for special effect’ (cf. Martin, Reference Martin2002: 398). Such ads contain individual nonce terms or entire phrases that have been translated from English. Moving further along the continuum to the left, the next category is that of partial substitution (host L ←→ English). This signifies ‘non-Anglophone ads in which English elements are literally embedded within non-English [i.e. local language] lexical items’ (Martin, Reference Martin2002: 397). This occurs, for example, when borrowing an English word and adding affixes of the host language (cf. Martin, Reference Martin2002: 397). Moving further to the left, the fourth category is ‘isolated lexical substitution (host L → English),’ where only ‘a single English word is inserted’ (Martin, Reference Martin2002: 394) into an advertisement otherwise in the host language (cf. Martin, Reference Martin2002: 394–396). The next category, ‘phrasal substitution (host L → English)’ (cf. Martin, Reference Martin2002: 389), denotes host-language advertisements with usually ‘product names containing two or more English words’ (Martin, Reference Martin2002: 389). The following category is what Martin (Reference Martin2002: 387) labels as sentential substitution (host L → English), referring to ads that ‘contain one or two full English sentences’ (cf. Martin, Reference Martin2002: 387). This is the final category before the left pole of ‘English monolingual’.

Analysis of outdoor advertisements

Code-mixed advertising with English elements

The advertisement in Figure 2, with the distinctive phrase Happy Soldes (Happy Sales), is an example of an isolated lexical substitution (host L → English). Appearing at the top of the ad in a big font and bright colors, this phrase serves as an attention-getter. Bhatia (Reference Bhatia1987: 35) notes that the text of an attention-getter is usually short and rarely constitutes a full sentence. In the case of an isolated lexical substitution, ‘a single English word is inserted for socio-psychological effects’ (Martin, Reference Martin2002: 394). Within the context of Morocco, this advertisement for furniture, prominently containing the English lexical item happy, conveys a sense of modernization, utility, quality, and innovation.

Figure 2. Isolated lexical substitution (host L → English) in a home furniture poster ad located at the side of a road in a business district

It is not clear whether happy was used here for its meaning as an independent lexical item or in reference to its role as the adjective in the widely-known noun phrase happy birthday. In the case of the former, happy may be used here to convey to customers a sense of a joyful and pleasant experience shopping for trendy home furniture. It may mean that the sales are exceptional, and customers will be fully satisfied with what is on offer. In the latter case of referencing the noun phrase happy birthday, happy may be used to congratulate the consumer, with the sale being viewed as a rare occasion to be celebrated, just like a birthday. In either case, using the English term is unlikely to create comprehension problems. The word is already quite widely known within the Moroccan speech community, even among individuals with modest English proficiency.

The next poster advertisement, in Figure 3, uses a phrasal substitution to promote apartments and parcels of land for sale on Morocco's northwest coast.

Figure 3. Phrasal substitutionFootnote 2 (host L → English) in a real estate development poster ad

The nominal phrase summer days, appearing in capitalized navy blue font, represents the largest words in the advertisement and therefore is another example of an ‘attention-getter’ (Martin, Reference Martin2002: 387). As is the case in the previous poster ad with the isolated lexical substitution happy, the two lexical items here do not have cognates in French or any of the other languages widely used in the Moroccan speech community. Nevertheless, the ad's copywriters apparently are confident that their target audience will comprehend this vocabulary. The terms summer and days in fact are amongst the 1,000 most frequently used words in English (West, Reference West1953; Browne, Culligan & Phillips, Reference Browne, Culligan and Phillips2013), making it likely that even Moroccans with limited proficiency will know these two terms. To further ensure comprehension, the background picture of a sunny beach functions as a contextual aid to reinforce the meaning of this attention-getter. In her study of English use in advertising in France, Martin (Reference Martin2007: 184) notes that visual clues frequently are employed for glossing in cases where English vocabulary may be unfamiliar to the audience. The used ‘illustration [often] underscores the meaning of English elements appearing in prominent positions of the advertisement’ (Martin, Reference Martin2008: 61).

In Morocco, high-end real estate development companies such as the advertiser in Figure 3, Prestigia Luxury Homes, frequently use French in their ads in order to stand out in the market. Using English here creates an added socio-psychological effect, suggesting an even higher degree of quality, sophistication, luxury, and exclusivity. In the Moroccan context, the English phrase summer days conveys a heightened sense of a relaxing and inviting lifestyle in a scenic, warm location. This additional English use has a stronger impact on the consumer than a monolingual French ad would have.

Phrasal substitution is also used in the wallscape advertisement shown in Figure 4, which is for a residential building called Urban Square II. According to Piller (Reference Piller2003), a switch into a foreign language in advertisements most often occurs at the level of product and company names (cf. also Martin, Reference Martin2002: 389; Bhatia, Reference Bhatia, Kachru, Kachru and Nelson2006: 606; Bhatia & Baumgardner, Reference Bhatia, Baumgardner, Kachru, Kachru and Sridhar2008: 389). This example of using English for the product name attracts the attention of potential customers (Amiri & Fowler, Reference Amiri and Fowler2012: 299). At the same time, the outdoor ad has the socio-psychological effect of creating a sense of prestige and an atmosphere of a modern, cosmopolitan lifestyle, as has been found also in other studies (see Martin, Reference Martin1998: 162; 2006: 167).

Figure 4. Phrasal substitution (host L → English) in a residential building wallscape ad

When the company's website promoting this real estate property was still accessible in 2014, it provided a virtual tour through the apartment units. The apartments were technologically advanced, with a striking open-concept, Western style of architecture that is markedly different from the type of accommodations with which most Moroccans are acquainted. For example, the housing units had parquet flooring instead of the traditional tiles or mosaic flooring found in Moroccan architecture, and plain ceilings rather than engraved plaster ones. The kitchens were open to the living-rooms, as opposed to being closed-concept with separate rooms that maintain traditional privacy for women, especially when male guests are present. In line with Bhatia's (Reference Bhatia1992: 213) findings, the English name of the residential building connotes a sense that the apartments are of high quality. In the Moroccan context, Urban Square II communicates an understanding of a modern, progressive design that is new and sophisticated, yet comfortable.

While the previous examples demonstrate how English appears in advertising written predominantly in French, Figure 5 shows that English also is integrated into advertisements in Arabic. The Arabic text in the upper left-hand corner translates as ‘new’, while the lengthier passage in the upper right-hand corner states ‘designed to save you fuel’. The Shell Oil Company product name FuelSave Diesel 50 again falls under the phrasal substitution category (host L → English). The product is an additive-enriched fuel that drivers can purchase to help improve their cars’ mileage. While FuelSave Diesel 50 is the product's complete name, only half of it, FuelSave, appears in English; Diesel 50 is written in Arabic. It is difficult to estimate how intelligible the product name is to a potential customer, but the ad's visuals do enhance the message of the product name. The accompanying picture of a male laboratory scientist holding a glass beaker conveys the sense that the product is e.g. scientifically tested, effective, clean, and engine-friendly.

Figure 5. Phrasal substitution (host L → English) of product name in a poster adFootnote 3

English is a common element in automotive industry advertising in general. While the previous ads use English in attention getters and product names, an advertisement for the French car company Renault (Figure 6) presents English use in a slogan. Appearing in the bottom right corner of the ad, drive the change is an example of sentential substitution (Martin, Reference Martin2002: 387), since a full imperative sentence is utilized (Martin, Reference Martin2002: 387, 399).

Figure 6. Sentential substitution (host L → English) of a slogan of a car company in a poster ad

Moroccans are well familiar with the French origins of this automobile company, so the choice here to use English instead of French takes on an added significance.Footnote 4 The English slogan presents a new image of the car company in the Moroccan context, while communicating also that the performance of its automobiles has improved.Footnote 5 A stated aim of the company is ‘to make sustainable mobility accessible to all’ (Group Renault, 2011). The slogan, written in English instead of the company's traditional language of French, invites the audience to drive not the old Renault automobile they are familiar with, but a new, transformed model. The English slogan demonstrates how a company can distance itself from its national identity to adopt, in this case, a globalized one.

A review of the Renault auto manufacturer websites for Morocco and for France in 2014 furthermore revealed differences in how the company advertised at the time to these two different French-speaking communities. In France, the slogan appeared as changeons de vie, changeons l'automobile, while in the combined markets of Morocco and Algeria it appeared in English as drive the change.Footnote 6 Pompey (Reference Pompey2015) states that the slogan drive the change was created specifically for anglophone countries, while changeons de vie, changeons l'automobile was used for francophone speech communities. Morocco and Algeria, however, have been using French for more than a century. This inconsistency regarding language choice in different French-speaking contexts was clarified later in 2015, when Renault launched its current slogan, Passion for Life or La vie, avec passion, in English and French, respectively. Guillaume Boisseau, Brands Director of Renault, explained that ‘the new tagline will be in English worldwide, consistent with Renault's international ambitions, though we will be translating it in France, our birthplace and historic market: “Renault – La vie, avec passion”’ (Group Renault, 2015).

One possible explanation for this difference in language choice is France's renowned Toubon Law No. 94-665 of 1994, which mandates using French in all advertising within the country. There are, however, notable exceptions to the regulation that make it possible to use foreign languages in ads appearing in France. Other languages may be used as long as a French translation also appears in the ad. In the case of slogans, these in fact may appear without translation as long as the foreign language phrasing has been copyrighted (Martin, Reference Martin2008: 53).Footnote 7 Given this fact, the copywriters in France could have used the English slogan had they deemed it appropriate and effective for that context.

A historically French company using the English slogan within the Moroccan context, where a French equivalent in fact was used in France for the same product, is especially noteworthy. This occurred in spite of the historical colonial ties between France and Morocco, as well as the strong contemporary business relations between the two countries. As noted in the sociolinguistic profile earlier, French continues to play a primary role within the Moroccan speech community, as it is the main language of numerous powerful domains. Still, the auto manufacturer chose to use an English slogan over the existing French counterpart. This suggests, that, at least in this particular case, English has an enhanced effectiveness within the Moroccan context, something that could not be achieved by using French alone.

Monolingual English advertising

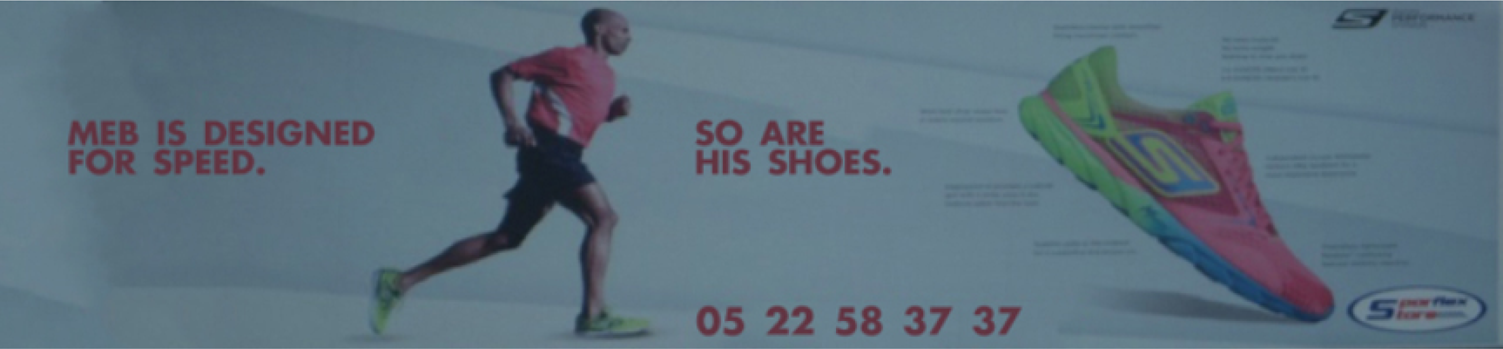

Figure 7 shows an English monolingual bulletin advertisement (see also Martin, Reference Martin2002: 385–387) for running shoes made by Skechers, a US-based company that sells its products in more than 160 countries and territories around the world (Skechers USA, Inc., 2018). The ad shows the image of a man in full running stride with the text Meb is designed for speed. So are his shoes in large letters.Footnote 8 A variant of this ad appeared the same year on the Skechers website for the United States, but with the word ‘built’ instead of ‘designed’. The fact that in Morocco the bulletin ad read ‘Meb is designed for speed’, but in the company's US website read ‘Meb is built for speed’, is striking. As was illustrated in the previous ad for the Renault automobile company, this intentional and meaningful deviation (see Kachru, Reference Kachru and Kachru1992) illustrates how users of a language adapt the code to the specific context in which it is used.

Figure 7. English monolingual bulletin advertisement for sport shoes located alongside an arterial road in Casablanca

In multilingual Morocco, proficiency in English is still relatively modest, as the language only recently began gaining wider functional range and greater societal depth. Proficiency in the four languages and their varieties that have been dominant in the country for at least a century – Tamazight, Arabic, French, and Spanish – is in general much higher. A plausible explanation for the choice to use ‘designed’ in the Moroccan bulletin ad instead of ‘built’ is to ensure better comprehension within this context. The participial adjective ‘built’ could cause intelligibility issues, as the usage here is somewhat idiomatic. On a fundamental level, structures and objects are ‘built’, but people are not. ‘Designed’ has a primary reference to structures and objects also, but this term is arguably easier to interpret within the Moroccan context because this English term originally was borrowed from French.

The choice to vary the wording between these two contexts illustrates further that language use, in this case English, is carefully considered in advertising. Rather than choosing the more expedient, less costly option of using the identical advertisement in both contexts, the copywriters apparently decided against using an English word less likely to be understood by the target audience. This deliberate deviation in word choice further demonstrates that in this ad English certainly is employed for communicative purposes, and not solely for aesthetic reasons or for branding. Had the latter in fact been the case, there would have been no need for the lexical difference between the two ads.

Using English here moreover functions as a reminder of the product's country of origin, which has significance for the Moroccan consumer. Some Moroccans may not necessarily be familiar yet with the Skechers brand; however, using English gives the product a Western identity. That identity becomes more specific with the portrayal of Meb Keflezighi, an African immigrant to the United States who has become a star athlete for that country. The use of English with Keflezighi as a spokesperson therefore establishes a connection between Africa, where the target audience is located, and the product's American origins (Skechers USA, Inc., 2018). In addition, English functions as a token of the product's reliability (Martin, Reference Martin2007: 175), suggesting high standards of quality, durability, and comfort to the Moroccan audience.

Pure pleasure is inside is the slogan for Nespresso, a brand of coffee and espresso machines which have accompanying single portion-size containers of different flavored coffee beans. Manufactured by a branch of the Nestlé Group of Switzerland, these products also are sold around the world. The wallscape ad in Figure 8 does not show an image of the machine itself or of the different types of single-portion capsules available. Instead, it is an example of ‘prestige advertising,’ where the aim is to enhance the product's overall image and status rather than show the actual object being sold (Vestergaard & Schrøder, Reference Vestergaard and Schrøder1985: 1). This status enhancement is achieved largely by the picture of George Clooney, the American film actor and well known international celebrity. The image communicates that Nespresso is a world-class coffee, a message that also appeals to Moroccan customers.Footnote 9

Figure 8. English monolingual wallscape advertisement for coffee appearing on the side of a building

This message is reinforced by the use of English for the slogan pure pleasure is inside, variants of which were used by the brand internationally (Comunicaffe International, 2013). Appearing in bigger font to attract the attention of Moroccan coffee lovers, the noun phrase pure pleasure is an example of English words with French cognates (pur plaisir). Despite its Swiss origin (Nestlé Nespresso, 2018), the company employs English to adopt an international identity, with this language choice conveying a notion of quality, taste, and originality. In using English, the ad communicates that consumers of Nespresso will feel sophisticated, chic, and elegant (see also Martin, Reference Martin1998: 166).

Figure 9 shows storefront signage on a poster stand displayed at an American Eagle clothing store in the Morocco Mall shopping center in Casablanca. This example is particularly interesting, as it is high in textual content with only sparse visual images that convey little information about the text's meaning. As such, the promotional advertisement presupposes that the targeted customers have a higher proficiency in English than is typically the case. At present, most Moroccans would have difficulty comprehending such a text-heavy advertisement, which might lead to an assumption the ad originally was designed for a foreign market rather than local Moroccan consumers. The abbreviation ‘DH’ in the text, however, stands for the Moroccan Dirham currency, indicating that the advertisement in fact was adapted, if not explicitly prepared for the context in which it is displayed.

Figure 9. English monolingual advertisement for clothing appearing in storefront signage in a shopping mall

The likely explanation for such a monolingual English ad with extensive text and little visual clues for meaning is the retailer's target demographic. The age range of American Eagle's primary customers is 15 to 25 years (Driscoll, Reference Driscoll2007), a segment of Moroccan society that now has English instruction in secondary and tertiary education. The company communicates with this population at a higher level of English proficiency, rendering the ad less accessible to other segments of the local speech community. As such, English functions here as a filter, enabling the ad to speak in a more targeted way to the company's primary demographic. This also has the socio-psychological effect of giving those consumers a feeling of worth and sophistication (Martin, Reference Martin1998: 166).

In Figure 10, the English monolingual text of the wallscape advertisement announces the future opening of a store called American Factory. We are unfamiliar with any internationally operating company of that name, and an Internet search of the term failed to produce any results for a company website with the depicted logo. We therefore assume this to be a local or regional business, perhaps the first such store to open under this brand name. Should that be the case, this advertisement has a distinct significance, as it would be an example of a local entrepreneur advertising exclusively in English. In other words, a local Moroccan business is using English instead of one of the country's historically primary languages to communicate with Moroccan consumers. This is in contrast to the previous examples of US- and overseas-based global corporations using monolingual English ads to target potential customers.

Figure 10. English monolingual wallscape ad for a clothing store

As in the previous ad for American Eagle, this monolingual wallscape advertisement is high in textual content with only sparse visual images, and therefore assumes greater English proficiency of its target demographic. Outdoor advertising often relies inversely on more visuals and less text, or on visuals that reinforce the message of the text. The heading of the advertisement, the assumed store name American Factory, is in large, capitalized font at the top, functioning as an attention-getter. The next line of text contains the English words OUTLET STORE 100% MADE IN USA. The lack of punctuation or variation in spacing makes these noun phrases difficult to parse. Most likely, it is the merchandise that will be sold in the store, rather than the store itself, that is made in the United States. Another line of English text follows below, alluding to the categories of products that will be sold: MEN, WOMEN, KIDS, HOME.

Despite the fact that the advertisement is solely in English, most of the words and phrases, such as American, made in USA, home, kids, men, women, are now common in chain store signs throughout Morocco. In the ad's bottom right corner the phrase coming soon appears, which nowadays is used widely by new businesses in Morocco, also in code-mixed ads written otherwise in French. The variant opening soon, another English phrase referring to a future business opening, is becoming more common in Morocco as well. In contrast, the French equivalent, ouverture prochaine, seems to be losing ground to these English counterparts, arguably because it no longer appeals to consumers as much as it used to in the past.

Two words in the advertisement, factory and outlet, are less likely to be known by Moroccans and therefore would require higher proficiency in English. There are no visual cues in the ad to clarify what factory and outlet mean, so the advertiser apparently is not concerned that a lack of comprehension could be problematic. The specific choice to speak of an outlet store is especially intriguing, since most Moroccans are not (yet) familiar with this retail concept. Common and indeed very successful in the United States as well as other countries, such stores are known for selling a quality brand's surplus or past seasonal merchandise at sharply discounted prices. As such, the English phrase outlet store generally means that well known brand items will be sold at bargain prices. This advertiser, therefore, appears to rely on the fact that some Moroccans are familiar with this foreign retail concept or at the very least are curious about it.

The store's English name and the accompanying advertising text, highlighting American and USA, imply that the merchandise for sale will be imported from the United States. Given the fact that relatively little retail manufacturing of apparel and home items is still done in the US for export, such a claim appears doubtful. Instead, by using English and these phrasings the advertiser most likely intends to give a certain identity to his products. The English words American and USA implicate the origin of the products, and the use of 100% serves as a token for quality and exclusivity.

Such marketing strategies are common when a product does not originate in a country that is famous for a particular type of manufacturing. The European appliance retailer Dixon, for example, used the Japanese-sounding word Matsui in the 1980s as a brand name for its own line of electronic ranges. This was done in order to associate their products with Japan's reputation for high-quality manufacturing. In effect, Dixon gave its products a Japanese-sounding name in order to sell more units (The Economic Times, 7 March 2008). A more recent example is that of the American reality TV show celebrity Kim Kardashian–West, who in 2014 sold a new perfume marketed under her name. She gave the fragrance, however, the French name Fleur Fatale to associate it with the fame and elegance of French perfumes.

Conclusion

Given the intricate form of multilingualism prevailing in Morocco through the end of the 20th century, it is hard to imagine yet another code gaining range and depth of use within this context. Moroccans have strong historical attachments to French, Arabic, Tamazight, and Spanish, and they speak several varieties of these languages.

Taking advertising as a window to Moroccan society, this paper shows that English in fact is becoming part of the local linguistic repertoire in this North African country. The forms of English use are wide-ranging, occurring at different points on Martin's (Reference Martin2002) cline for code-mixed advertising. They are not limited to single lexical items in code-mixed ads, but include full sentential substitutions appearing in monolingual English advertisements that assume relatively high proficiency in the language. Both domestic and international businesses employ English in outdoor advertising in order to be memorable and have various socio-psychological effects on potential customers. The ads use English to communicate information about the products that go far beyond what is stated in the texts themselves. The outdoor advertisements for the companies Prestigia Luxury Homes, American Factory, Skechers, and Urban Square II aim to create positive affective ideas and concepts, such as of modernization, Westernization, and attractiveness. In addition, they strive to communicate a sense of utility and superior quality, of sophistication and efficiency. Using English moreover gives an impression of reliability and durability in quality, of prestige and elegance in style. The language creates within the consumer a positive feeling about one's self and also a sense of trust. Further strengthening the value of these products is the fact that their qualities transfer to the individuals who purchase and use them (Piller, Reference Piller2003: 175; Kasanga, Reference Kasanga2010: 198).

The power of English as illustrated in these sample advertisements, and the inroads the language has achieved so far in other domains such as education, raise questions in particular about the status of French within the Expanding Circle context of Morocco in the coming decades. The majority of the code-mixed advertisements discussed above are in the host language of French with a heading or a product name in English. If copywriters feel compelled to add an English attention-getter, it may indicate that English is becoming more powerful than French in the marketing sphere of business. Local media outlets have written on many occasions about the need to strengthen Moroccans’ proficiency in English (Lemag.ma, 2014; Galla, Reference Galla2014; Amine, Reference Amine2015; Sfali, Reference Sfali2015). Today, English is introduced earlier in primary education along with French, and there are plans to employ it as a MOI in the secondary level. Although the French language seems to be deeply rooted in the Moroccan speech community, this analysis demonstrates that English is slowly, but surely, gaining ground, especially in the domain of advertising.

BOUCHRA KACHOUB received her MA degree in Applied Linguistics from Ohio University and is currently a PhD candidate at Simon Fraser University in Canada. Her areas of research interest include Sociolinguistics, Second/Foreign Language Learning, and Language Policy. Bouchra is particularly interested in the spread and use of English in the Expanding Circle country of Morocco vis-à-vis the multiple languages already in use. Her primary focus is in the domains of advertising, education, and media. Email: bouchra_kachoub@sfu.ca

BOUCHRA KACHOUB received her MA degree in Applied Linguistics from Ohio University and is currently a PhD candidate at Simon Fraser University in Canada. Her areas of research interest include Sociolinguistics, Second/Foreign Language Learning, and Language Policy. Bouchra is particularly interested in the spread and use of English in the Expanding Circle country of Morocco vis-à-vis the multiple languages already in use. Her primary focus is in the domains of advertising, education, and media. Email: bouchra_kachoub@sfu.ca

SUZANNE K. HILGENDORF is Associate Professor of Linguistics at Simon Fraser University in Canada, with expertise in Sociolinguistics, Second Language Acquisition, and Foreign Language Pedagogy. Her primary research area is World Englishes, especially the Expanding Circle and English use in Germany/Europe. She has published in peer-reviewed encyclopedias, edited volumes, and journals, including Language Policy, and (co-)edited special issues of World Englishes (2007) and Sociolinguistica (2013). She served as President of the International Association for World Englishes from 2013 to 2014. Email: skh7@sfu.ca.

SUZANNE K. HILGENDORF is Associate Professor of Linguistics at Simon Fraser University in Canada, with expertise in Sociolinguistics, Second Language Acquisition, and Foreign Language Pedagogy. Her primary research area is World Englishes, especially the Expanding Circle and English use in Germany/Europe. She has published in peer-reviewed encyclopedias, edited volumes, and journals, including Language Policy, and (co-)edited special issues of World Englishes (2007) and Sociolinguistica (2013). She served as President of the International Association for World Englishes from 2013 to 2014. Email: skh7@sfu.ca.