Introduction

For a very long time, women have been largely absent from large firms’ boardrooms in the so-called developed world, both at the strategic and executive levels. The situation has improved since the end of the twentieth century, although their presence remains low in comparison to men and is characterized by important differences across countries.Footnote 1 The recent inclusion of women on corporate boards has led to important public debates, notably concerning the controversial quota issue. It has also been extensively discussed in academic literature, in particular in sociology and management studies,Footnote 2 in which scholars have addressed a variety of issues related to “board diversity,” such as the impact of women’s integration in boardrooms on the firms’ performance—known as the business case argument—the profiles of female directors who managed to access board appointments, and the obstacles women continue to face in reaching such positions. However, most of these studies only focus on very recent times, and thus miss out on the underlying historical and political factors that have contributed to the long-term exclusion of women from positions of power.

This article aims at filling this gap and contributes to the existing literature on board diversity by carrying out an empirical analysis of the presence of women on the largest Swiss firms’ corporate boards across the past hundred years. Switzerland is a particularly interesting case study, as the presence of a female corporate elite is still very low in international comparison. However, women have been largely left out from research on Swiss business and corporate elites until now,Footnote 3 and Switzerland is usually not taken into account in the few existing comparative studies.Footnote 4 I argue that in order to understand the current situation, it is necessary to identify the historical and political factors that have contributed to the enduring exclusion of women and to take into account the social construction of gender. In this sense, insights from the Swiss case can also contribute to a better understanding of the obstacles that women continue to face in achieving board appointments around the world.

This article also aims at contributing to the existing literature on corporate elites by integrating a feminist analysis of these elites’ power, which remains scarce in comparison to analyses of working-class masculinity.Footnote 5 In order to do so, this research builds on a recent study carried out by Eelke Heemskerk and Meindert Fennema on the Dutch case – one of the rare long-term analyses of women’s inclusion in corporate elites.Footnote 6 As the authors argue, female presence on corporate boards can be considered a form of elite democratization, as it contributes to a better demographic representation of the population within this elite. In the Dutch case, the state initiated this process in the 1970s by giving seats on the boards of government-controlled firms to women. It was thus an “exogenous democratization,” in the sense that changes were not implemented by the corporate elites themselves.Footnote 7 In the subsequent period, internationalization contributed in an important way to the promotion of a female presence on the corporate boards, notably through the integration of foreign female directors. This article investigates to what extent the recent inclusion of women on corporate boards followed a similar pattern in Switzerland, another small and highly internationalized economy.Footnote 8

This article is structured as follows. The first section discusses the historical roots of female exclusion from the corporate elite and the subsequent exclusion of businesswomen from business history research. The following part gives an overview of the current debates related to board diversity. I then integrate Switzerland in an international comparison before presenting the method and data used in this contribution. In the next sections, I analyze my data set and discuss the long-term evolution of women’s presence among the largest Swiss firms for the past hundred years. This allows me to show that women have been sitting on the boards of family firms since the beginning of the twentieth century, although in very small numbers. Two major turning points contributed then to increase the presence of women on corporate boards, namely, the extending in 1971 of “universal suffrage” to women and, later, the increasing globalization and internationalization of the economy at the end of the twentieth century. The state played only a very marginal and late role. This leads me to come back to the more recent issue of quotas in the concluding remarks.

The Historical Exclusion of Women from Corporate Elites

For a long time, business history has largely ignored women’s contributions to business. To a certain extent, this omission resulted from the exclusion of women from leading positions in the business world, which was mostly a man’s world. In this sense, the understanding of the historical mechanisms that contributed to exclude women from corporate elites helps to offer a better understanding of the current challenges that women still have to face and to deconstruct the biological argument that tends to attribute different roles in society to men and women according to their biological sex. In fact, feminist authors have shown that the subjective identities of men and women have historical, social, and cultural origins.Footnote 9 Women’s long-term exclusion from corporate elites in Western societies is historically rooted in the fundamental inequalities of power based on sex, and more specifically in the division of labor between women and men that was built up during nineteenth-century industrialization.Footnote 10 The separation between the household and the workplace, which has ultimately been accepted as a “natural” division, was in fact, as underlined by Joan Scott, historically constructed by capitalist rhetoric.Footnote 11 As the author shows, industrialization in itself did not lead, contrary to common belief, to an inexorable separation between the household and work. According to her, the sexual labor division rather followed the idea spread by eighteenth- and nineteenth-century political economists, such as Adam Smith and Jean-Baptiste Say, that men needed to gain enough money to sustain the whole family, producing the figure of the male breadwinner. Meanwhile, women’s subsistence became dependent on men, and women involved in the labor market became second-rank workers, mostly confined to precarious employment and paid less than men when doing a similar job.Footnote 12

The sexual division of labor that had been established with industrialization persisted durably. The role model of the housewife, which became self-evident during the second half of the nineteenth century, implied that women had to stay at home in order to take care of the children.Footnote 13 For the working classes, domestic work did not in reality exclude wage-earning work, and women were often concurrently engaging in both activities. The situation was, however, different for women belonging to the middle and upper classes. The elites tended to associate women with sensitiveness rather than with intelligence and to confine them to the household, while the public sphere became the prerogative of men.Footnote 14

The gendered division of labor was translated into legal frameworks. With the first Industrial Revolution and the rise of family capitalism, married women were excluded from the independent legal right to businessownership over a certain period, which varied according to national context.Footnote 15 This does not mean that women did not take an active part in the family business, but it did lead “to a structural statistical underestimation” of their economic activities.Footnote 16 In many Western countries, women remained legally economically dependent on men during the twentieth century. In France, for example, women were considered in the civil code to be under the care of their fathers or husbands; until 1907, they did not have the right to use their salaries freely.Footnote 17 In Switzerland, the 1912 marriage law, which remained unchanged until 1987, decreed that the husband had to provide for the financial needs of the family, while the wife had to provide for the domestic needs—in other words, the household and the children. The husband even had the right to forbid his wife to work outside the house, if it was considered a threat to the marriage.Footnote 18 Both world wars had disputed effects on women’s position in the labor market—and more generally on women’s emancipation. The extended conflicts led to the temporary mobilization of women in the labor market and opened up new professional opportunities for them.Footnote 19 However, the ends of both world wars were followed by a strong resurgence in patriarchal conservatism, and real changes only occurred with the second-wave of feminism in the 1960s.Footnote 20 In spite of the important integration of women in education and the labor market, gender inequalities persisted during the twentieth century.Footnote 21 Generally speaking, women remained largely excluded from positions with responsibility, and all European countries are still characterized by a horizontal and vertical segregation according to gender.Footnote 22

Because of these structural gender inequalities, the economic history of women was essentially rooted in social and labor history and was relatively ignored by “traditional” economic and business history.Footnote 23 However, the long absence in historiography of researches investigating the contribution of women to business cannot be explained only by their marginal presence in leading positions. To a certain extent, it also ensued from the structure of the field of business history, which itself was dominated by male scholars who had rendered businesswomen invisible.Footnote 24 In this perspective, the 1990s represented a turning point: “After years of struggles for property rights, civil rights, and equal rights, women occupied enough seats on corporate boards, university faculties and government offices, and generated enough new businesses and large enough sales to make them seen and heard.”Footnote 25 In the field of business history, scholars began to reassess women’s participation in business activities during past centuries.Footnote 26 For instance, Josephine Maltby and Janette Rutterford have uncovered the important contribution made by women stock investors in both public and private English firms in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, showing that this contribution had been largely ignored by the literature.Footnote 27 Moreover, several scholars have contributed to highlight the invisible, but nevertheless crucial role of women in family firms.Footnote 28

The Turn of the Twenty-First Century and the Debates on Board Diversity

The increasing presence of women on corporate boards since the end of the twentieth century has also been widely discussed in sociology and management studies. It has notably become a predominant aspect of a broader discussion on board diversity, which also includes nationality, race, and ethnicity issues, in particular in the United States, where “all-male” and “all-white” corporate boards have been pervasive in large firms. Most of this literature, often rooted in management studies, tries to evaluate how women (or ethnic minorities) on corporate boards impact a firm’s performance.Footnote 29 This approach has, however, several limits, and has produced conflicting results.Footnote 30 First, it remains very difficult to empirically prove the link between board diversity and a firm’s performance, notably because it is hard to isolate the impact of gender on a firm’s performance from other factors of diversity, such as age or the time spent in the firm, and because women are still too scarce on boards.Footnote 31 Second, most studies take for granted the alleged differences between men and women. The effects on gender equality are thus ambivalent, because most of the time the studies that actually argue in favor of more “feminine leadership” contribute at the same time to reproducing gender stereotypes and, as a consequence, the gender division of labor.Footnote 32 Interestingly, alleged “feminine characteristics” such as risk aversionFootnote 33 or noncompetitive behavior,Footnote 34 which had been perceived for a long time as incompatible with leadership, have become more and more valued. The 2008 financial crisis contributed to this shift in perception, as the crisis was largely perceived as the consequence of a typically men-only risk-taking behavior.Footnote 35

In a more interesting and convincing way, several studies in the field of sociology and management studies have investigated issues other than the impact of gender on a firm’s performance, such as the profile of women who have succeeded in entering corporate boardroomsFootnote 36 or the remaining barriers to appointing female directors. In this regard, Val Singh and Susan Vinnicombe argued that the persistent exclusion of women in top UK boardrooms at the beginning of the twenty-first century cannot be explained by women’s lack of ambition, but rather by social identity, social networks, and cohesion theories, as elite male directors prefer candidates similar to themselves.Footnote 37 However, most of these studies focus on the contemporary period only and thus miss out on the underlying historical and political factors that have contributed to the enduring exclusion of women from positions of power, but also the factors that have led to their progressive inclusion.

Women on Corporate Boards: The Swiss Case in International Comparison

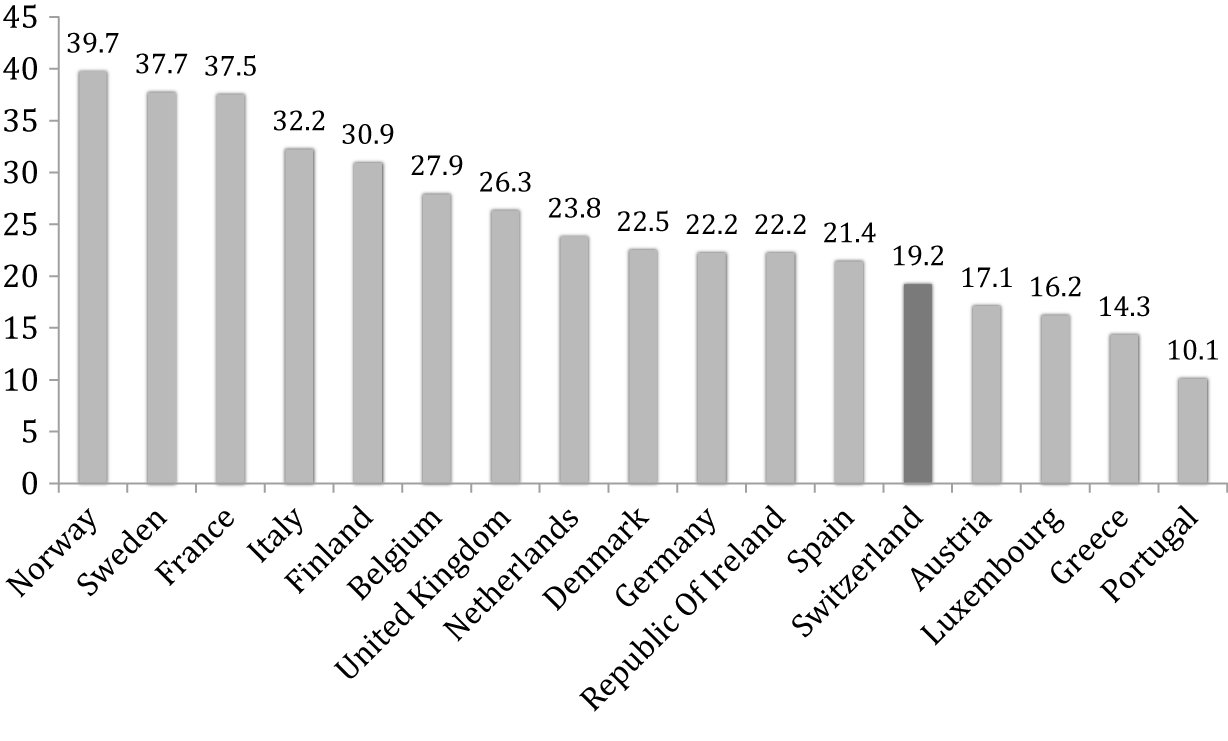

Egon ZehnderFootnote 38 has analyzed the 2016 level of gender diversity in the boardrooms of the world’s largest public companies, those firms with market capitalization exceeding €6 billion. Its findings show that Switzerland was clearly lagging behind other Western European countries, with a proportion of only 19.2 percent of women on boards against an average of 26.2 percent (Figure 1). As usual, this kind of international comparison must be interpreted with caution, because of the existence of different governance structures according to the individual countries,Footnote 39 and also because the constitution of the firms’ samples may differ from one country to another. Notwithstanding these limits, these comparisons allow some broad trends to be shown that are worthy of interest.

Figure 1 Percent of board positions held by women in the largest companies of Western European countries, 2016.

Source: Appendix to Egon Zehnder, Global Board Diversity Analysis (accessed April 21, 2017).

Seven countries are situated above the European average of 26.2 percent: Norway (39.7 percent), Sweden (37.7 percent), France (37.5 percent), Italy (32.2 percent), Finland (30.9 percent), Belgium (27.9 percent), and the United Kingdom (26.3 percent). Norway heads the table, as a result of the legislation targeting a figure of 40 percent of women on the boards of all public limited companies, which was passed by the Norwegian Parliament in November 2003.Footnote 40 Following Norway, a pioneer in the matter of quota, in January 2011 the French government passed a law, the Copé-Zimmermann Law, establishing gender quotas for corporate boards, also aiming at 40 percent of women on listed corporate boards by 2017.Footnote 41 Italy, Belgium, and Finland have also introduced quotas during recent years. Only two countries situated above the European average did not opt for the quota system. In Sweden, which is nevertheless second place in the table, the Parliament rejected quotas for women on boards of listed companies in January 2017.Footnote 42 The United Kingdom has also shown a strong reluctance toward quotas. There, the increase in women seems to be related to the release in 2003 of two reports, the Higgs Review and the subsequent Tyson Report, which both recommended the inclusion of more women and ethnic minorities on UK corporate boards.Footnote 43 Despite an overall progression of the female presence on corporate boards, women remained largely absent from the most powerful roles in the firm, such as chairperson or CEO. Indeed, women held less than 4 percent of the CEO roles in Egon Zehnder’s research sample.Footnote 44 The assessment also applies to the United States, although at the beginning of the twentieth century women represented almost half of the U.S. labor force.Footnote 45

With only 19.2 percent of women on the boards of the largest firms, Switzerland clearly lagged behind most European countries, as only Austria (17.1), Luxembourg (16.2), Greece (14.3), and Portugal (10.1) were doing worse in terms of gender equality. Several studies have highlighted the persistent exclusion of women from the boards of the largest Swiss firms.Footnote 46 These studies, however, are mostly bringing this exclusion to the readers’ attention rather than addressing the issue. Authors adopting a long-term perspective show that men dominated the boards of the largest Swiss firms during the entire twentieth century.Footnote 47 Board recruitment relied on a process of co-optation, in which elite men chose other men to sit at their side. The male corporate elite became a very cohesive group, thanks notably to the small size of the country. Things began to change during the last decade of the twentieth century, with the quickening of economic globalization, the affirmation of the shareholder value ideology, and the growing internationalization of firms, which had a strong impact on Swiss corporate governance and on the profile of the elites leading the Swiss firms.Footnote 48 Several scholars have shown how these changes have contributed to the decline of the Swiss corporate networkFootnote 49 and to the increase in foreigners among the corporate elite,Footnote 50 with some studies showing how both aspects are interrelated.Footnote 51 However, the impact of these changes for women remains largely neglected in these researches.

Data and Method

The present study stems from a collective research project on Swiss elites, the aim of which is to analyze the Swiss business, political, and administrative elite in a long-term perspective. For this purpose, we have created a large database and collected biographical information for the elites of the three spheres across the past hundred years for different benchmark years (1910, 1937, 1957, 1980, 2000, 2010, and 2015).Footnote 52 The choice of the dates was made so as to take into consideration different stages in the history of Switzerland, but it was also influenced by the availability of the data. For the economic sphere, the 110 (on average) largest Swiss firms for each benchmark year were selected, including the industrial, services, and financial sectors.Footnote 53 For the industrial and services sectors, companies were selected according to the turnover and the number of employees and according to market capitalization for the more recent period. For the financial sector, total assets represented the main criterion in order to select the most important banks, insurance companies, and finance companies. A number of very different sources were used, such as stock exchange manuals, financial yearbooks, monographs about individual companies, and annual reports of firms. For the more recent period, data were mostly derived from annual reports and from companies’ websites.

Following Mills, we define elites as persons who “are in a position to make decisions having major consequences.”Footnote 54 The Swiss corporate governance system is marked by a one-tier board system. The board of directors can either delegate the management of the firm to professional managers who are not themselves board members, or they can conduct company business themselves (they are then designated as administrateurs-délégués, hereinafter managing directors). The Swiss corporate elite comprises then, for each firm and each benchmark year, the members of the board of directors, the general director, and when they exist, the managing directors. Ultimately, 808 persons in 1910, 739 in 1937, 829 in 1957, 886 in 1980, 852 in 2000, 891 in 2010, and 932 in 2015 were identified as representing the corporate elite. We have collected systematic information for each person concerning the sex, nationality, and position(s) held in the 110 largest Swiss firms.

For the present contribution, I have identified for each benchmark year the number of women sitting on boards of directors and holding a top executive position. I have then collected more detailed biographical information for these women, notably concerning their social origins and their potential kinship ties to the family owning the firm in the case of family firms. Different sources were used, such as genealogical almanacs, biographical dictionaries, press articles, and for the most recent period, companies’ websites.

(More Than) One Century of Exclusion

The database allows the tracing of the long-term evolution of women among corporate elites and also a comparison of this evolution with the position of women among political and administrative elites. Table 1 shows that women have been mostly excluded from positions of power in these three spheres during the main part of the twentieth century. Interestingly, the table shows, however, that while women were almost totally absent from both political and administrative elites for a long time, they were present among the corporate elite, even though in a very faint proportion. Changes are visible from the 1980s, as women became more and more important in the political and administrative elites. In fact, as we will see later, 1971 was a turning point, as Swiss women finally obtained the right to vote and to be elected at the federal level, a right that had already been accorded to men in 1848, with the birth of modern Switzerland and the introduction of the Federal Constitution. Quickly, this important change in Swiss legislation led to the entry of women into the Swiss ParliamentFootnote 55 and, later on, into the Federal Council, which is the highest executive authority in the country. Thus, in 2015, we find that 30 percent of the political elite are women. In all likelihood, this had an impact on other spheres, as we can observe an increase in women among administrative and economic positions: in 2015, women represented 22 percent of the administrative elite and 15 percent of the corporate elite.

Table 1 Women among the Swiss elites.

Note: Corporate elite: board of directors, general director, and managing directors of the 110 largest Swiss firms. Political elites: members of the Swiss Parliament, the Federal Council, the Conseil d’Etat of the 26 cantons, and the executive committees of the governmental political parties. Administrative elites: members of the Federal Chancellery, chief administrative officers of the federal departments, directors of all federal offices, members of the executive boards of the Swiss National Bank and members of the Federal Supreme Court of Switzerland.

Source: Swiss elites database, accessed June 22, 2019, www2.unil.ch/elitessuisses.

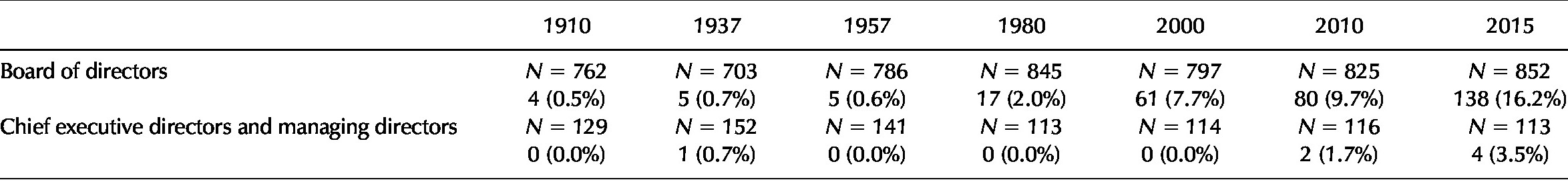

As is shown very clearly in Table 1, changes were remarkably slow to happen on corporate boards. Moreover, the progression of women holding an executive position in the firms (general director and managing director) was even slower, reaching barely 4 percent in 2015, as shown in Table 2. The few women who were present in the largest Swiss firms were thus mostly confined to the boards of directors, where we observe a much clearer increase since the beginning of the twenty-first century.

Table 2 Women among the Swiss corporate elites according to their position in the firm.

Note: As there is no legal obligation for a separation of tasks between the board of directors on the one hand, and the management and executive positions on the other hands, several persons hold both positions and are thus counted in both samples. As a consequence, the addition of both samples for each year is higher than the total number of corporate elites indicated in Table 1.

Source: Swiss elites database, accessed June 22, 2019, www2.unil.ch/elitessuisses.

The next sections analyze further the evolution of women on Swiss corporate boards, according to the three main stages identified in Tables 1 and 2. The first one corresponds to a major exclusion of women during the largest part of the twentieth century, the second one to the weak increase observed at the beginning of the 1980s, which “speeded up” during the last phase—the period from the end of the twentieth century.

Family Capitalism and the Invisible Role of Women

As shown earlier, the labor division between women and men and the corresponding separation between the household and work was built up during nineteenth-century industrialization. Women were excluded from leading positions in the economic sphere in general and thus in large firms from the first Industrial Revolution, which started in Switzerland during the first half of the nineteenth century. This appears clearly in Tables 1 and 2, as women represented less than 2 percent of the corporate elite during the main part of the twentieth century. More precisely, we find 4 women to 804 men in 1910, 6 women to 733 men in 1937, and 5 women to 824 men in 1957. These women were in various economic sectors, but they sat on the boards of directors of firms owned by their families, most of the time with a male member of the family. For example, in 1910, Elise Hoffmann-Merian (1845–1913) was sitting on the board of the chemical firm Roche with her son, Fritz Hoffmann-La Roche, who had founded the company with his father in 1894. In 1937, Marie Hasler-Simpson (born in 1914) was a board member of the Hasler company with her husband, Gustav Hasler. The latter had taken over the telecommunications company after the death of his father in 1900 and had turned it into a public firm. In 1957, Selina Dätwyler-Gamma (1902–1993) was sitting with her two sons on the board of directors of Dätwyler AG, a wire and rubber manufacturer owned by her husband Adolf Dätwyler. With the one exception of Else Selve-Wieland (1888–1971), who was in 1937 chairwoman and managing director of the metalworking company Metallwerke Selve, the few women who were present in large Swiss firms had no access to the highest positions. The unusual case of Else Selve-Wieland can be explained by the fact that she became the only owner of the firm after the death of her husband in 1933.

Even if these women remain exceptions, they are worthy of mention, because they are illustrative of the invisible—but nevertheless essential—role that women played during a time when corporate governance was dominated by family capitalism. Families and family firms indeed played a key role during the first phase of the Industrial Revolution and continued to play a decisive role in twentieth century capitalism.Footnote 56 In Switzerland, family capitalism remained very important until the 1980s.Footnote 57 As underlined by Colli and Rose, “Women play a crucial role in family business although their formal status, even today, is often hidden.”Footnote 58 They were notably essential actors in the preservation and transmission of family patrimony among the capitalist class. They contributed to weaving alliances among industrial families through marriage, thus extending the “family network of trust.”Footnote 59 For example, Elise Hoffmann-Merian belonged to the very upper-class Merian family of the canton of Basel, which was involved in wholesale trade and capital export. Else Selve-Wieland was the daughter of businessman Philipp Jakob Wieland and Lydia Sulzer, who belonged to one of the most important families in the Swiss machine industry. The father of Selina Dätwyler-Gamma, Martin Gamma, belonged to the political elites of the canton of Uri, where the Dätwyler company was established. Selina’s husband, Adolf, was a self-made man of modest origins who made a career in the Schweizerische Draht-und Gummiwerke AG, which he rechristened with his own name after he managed to straighten out the firm and to purchase all the shares in 1917. In 1924 he married Selina Gamma, which contributed to his upward mobility. It should be underlined here that this opportunity of social mobility through marriage existed for men when they were considered to “deserve it,” but not for women.Footnote 60

Many invisible women, in the sense that they did not gain access to the boards of the firms, have nevertheless played a similar role. For example, Heinrich Wolfer (1882–1969), managing director of Sulzer in 1937, had in 1908 married Lucie Sulzer, the daughter of Jakob Sulzer, an associate of the family firm since 1888. Two years after his marriage, Heinrich Wolfer joined the firm, where he then spent his entire career. In other words, these women remained excluded from strategic positions in the firm, while giving access to these positions to new members integrating into the family through marriage.

In addition to their crucial role in weaving alliances among industrial families, women were usually expected to perform duties related to the family firm, such as assisting their husbands, preparing the next generation to take over the company, and maintaining social networks.Footnote 61 For example, Renée Schwarzenbach-Wille (1883–1959), the wife of Alfred Schwarzenbach, whose family owned the largest silk industry company in the world after World War I, played an active role in the cultural life of Zurich, the city where the couple resided. As the vice president of an international music festival, she organized in 1920 and 1922 a major reception in the family house, gathering many artistic and intellectual personalities, including the winner of the Nobel Prize in Literature, Hermann Hesse.Footnote 62

During the greatest part of the twentieth century, the Swiss corporate elite was thus mainly a male bastion, with a few exceptions. As mentioned earlier, the enduring exclusion of women from the boards of large firms took place in all Western societies. However, some factors specific to Switzerland can be highlighted. First, board members were only recruited through a system of co-optation. In this process, corporate elites tended to choose people belonging to the same social categories as themselves, to the detriment of women as well as men of more modest origins.Footnote 63 Holding a rank in the army played a very important role in this process: indeed, during the twentieth century, about 50 percent of the Swiss corporate elite were or had been officers in the Swiss army.Footnote 64 Following the militia principle, every male Swiss citizen over the age of legal majority has to enroll in military service. Pursuing a military career was particularly important in selection of elites in Switzerland, because as in Germany but unlike France, there were no institutions dedicated specifically to the training of elites. In this sense, holding a rank in the army could be valued as showing leadership ability. Moreover, the time spent in the army contributed to a process of socialization among its members, strengthening their social cohesion. The importance of a military career in accessing a board appointment thus constituted an indirect obstacle for women, as the army was only compulsory for men. Finally, the fact that women did not have the right to vote and to be elected at the federal level for a very long time contributed in a decisive way to confine them to the private sphere.

The Right to Be a Citizen: A Tipping Point

As underlined by Fraisse and Perrot, the advent of democracy in Western societies during the nineteenth century was not a priori in favor of women.Footnote 65 Indeed, they had to wait until the following century to obtain full political rights, which happened at very different times in different countries. In a comparative perspective, Switzerland clearly lagged behind. Indeed, full political rights were introduced in 1906 in Finland, in 1913 in Norway, and in 1915 in Denmark and Iceland, while most other Western countries followed in their predecessors’ footsteps after World War I, such as Austria in 1918 and Germany and the Netherlands the following year.Footnote 66 Although Switzerland did not directly take part in the world wars, Swiss women, and especially those belonging to the lower classes, were called up in order to stand in for men during the war mobilization. But they did not receive, as in other countries, the right to vote in return.Footnote 67 Swiss conservatism on this issue was particularly striking, as Swiss men were given the right to vote and to be elected early on, with the 1848 Federal Constitution. Women had to wait 123 years to gain access to this fundamental right at the federal level. Women’s suffrage was introduced in 1958 in the municipality of Riehen, in the canton of Basel-Stadt, but the following year, the (male) population voted against the proposition of the Federal Council concerning women’s suffrage at the federal level.Footnote 68 Until 1971, to be a “citizen” thus meant to be a man,Footnote 69 and the long struggle for women’s suffrage had multiple consequences. As underlined by Patricia Schulz, until the beginning of the 1970s, not only was the entire Swiss legal system elaborated without women having a real power of decision, but the fact that the fight led by feminist movements focused essentially on women’s suffrage led to important backwardness in other regulations related to gender as well, such as social legislation.Footnote 70 This reinforced the obstacles for women in the labor market, as Swiss legislation was, and still is, particularly underdeveloped when it comes to childcare. For example, maternity leave only became effective in 2005, after a ten-year debate.

In the Netherlands, the second feminist wave of the 1970s did not directly demand female representation in the boardroom, but played an indirect role by insisting upon representation in the political arena and equal rights in the labor market.Footnote 71 The democratization of the political elite then had an impact on the corporate elite, as female politicians entered the boardroom. Moreover, their arrival was initiated by the state, as state-controlled firms were the first to open their boards to women.Footnote 72 The Swiss situation was partly similar. At the beginning of the 1980s, women already represented 10.4 percent of Swiss ParliamentariansFootnote 73 and 10.3 percent of all the political elite (see Table 1). In a less significant way, we observe a slight increase in women in the corporate elite, too, compared with the previous decades. Moreover, the seventeen women concerned exhibited a different profile than their predecessors. Although two of them were still sitting on the boards of firms owned by their families—Hortense Anda-Bührle in Oerlikon-Bührle and Suzanne Mijnssen-Gyr in Landis & Gyr—the others had no family connection with the owners of the companies. Several of them were political activists. A typical case was Annie Dutoit (1909–1999), who had to work as a secretary in order to pay for her law studies, as her parents were opposed to her getting a legal degree. She became a lawyer, then a member of the Conseil communal in Lausanne (the legislative organ of the city), and in 1968 its first female president. She also presided over the Liberal Party of Lausanne.Footnote 74 In 1972, she became a member of the board of directors of the department store Innovation, and even its chairwoman in 1979—the second woman of our sample, after Else Selve-Wieland, to accede to this position. Rosmarie Michel (born in 1931) is a more ambiguous but nevertheless interesting example. Initially, this woman belonged to a business family, as her father owned a confectionery store in the city of Zurich, which she took over in 1956. Thus having a foot in the business already, Rosmarie became a feminist activist, campaigning for better integration of women in the economy. She was notably a member of the International Federation of Business and Professional Women from 1977 to 1989—and its chairwoman from 1983 to 1985.Footnote 75 At the beginning of the 1980s, she was a member of the board of directors of Merkur, a firm selling coffee and chocolate through a network of subsidiaries scattered throughout Switzerland. As these examples show, although things began to change slowly, some gender stereotypes were taking place at the same time. Indeed, almost all of the women (i.e., thirteen out of the seventeen) present in 1980 on the boards of directors of the largest firms were cooped up in the usually “female-oriented” and “softer-side”Footnote 76 distribution and retailing sector. Moreover, most of these firms were cooperatives.

As in the Netherlands, the 1970s were thus a turning point, with important changes implemented in the political sphere. Contrary to the Dutch case, however, the inclusion of women in the boardrooms from the 1970s was not initiated by the state. Indeed, none of these firms were owned by the state, with the exception of the Banque populaire Suisse, which was only partially owned by the state. In fact, as we will see later, the Swiss Federal Council only decided to introduce a quota of women on the boards of directors of the large firms close to the Swiss Confederation in 2013. The process of elite democratization that began to take place resulted thus from a relative opening of the distribution and retailing sector to women, probably for economic purposes: the managers of these companies, which target a predominantly female audience—and more specifically housewives—most likely hoped to get to know their customers better by appointing women to their boards of directors.Footnote 77 The next important change that contributed to greater inclusion of women in the corporate elite was the economic globalization and internationalization that took place at the end of the twentieth century and challenged in an important way the Swiss corporate governance system and the corporate elites, whose profile had been very stable until then.

Economic Globalization and the Increase in Female Board Membership

Since the last decade of the twentieth century, the Swiss corporate governance system has undergone some deep changes. Switzerland began to converge more and more toward the liberal model during the quickening of economic globalization.Footnote 78 This evolution led to a reconfiguration of the field of Swiss business elites: national resources, such as the army, degrees in Swiss universities, and national networks, became less important than experiences gained abroad and international networks.Footnote 79 This also led to a remarkable increase in the proportion of foreigners among the corporate elite. In 1980, these foreigners represented only 3.7 percent of the corporate elite of the 110 largest Swiss firms; in 2000, this proportion reached 23.9 percent, and in 2010, 35.5 percent.Footnote 80 The internationalization of the corporate elites was especially strong in Switzerland, by comparison with other European countries,Footnote 81 and contributed to decreasing cohesion among the Swiss elite and to the decline of interfirm ties.Footnote 82

This evolution was also closely related to a partial transition from family to investor capitalism.Footnote 83 Several groups of actors, such as large banks and financial companies, institutional investors, but also corporate raiders and financial analysts, actively promoted a change in large firms’ strategies, which became oriented more toward the maximization of shareholder value.Footnote 84 The ideology of shareholder value had been dominant in corporate governance from the 1980s among U.S. and UK firms, before spreading progressively in European countries.Footnote 85 In Switzerland, historical stockholders such as families became less important. All these changes weakened the cohesion of the ancient elite, thus providing an opportunity for new elites. The decline of interlocking directorates among Swiss firms from the 1990s, for example, meant that fewer board members were co-opted from among other large Swiss firms than before. Although this mostly benefited the foreigners, women were able to lower the glass ceiling a little bit more.

In 2000, women represented 7.2 percent of the Swiss corporate elite, and this proportion reached 15.1 percent in 2015. Although this remains a small proportion in comparison to other Western countries, the increase is noticeable compared with the previous decades (see Table 1). The proportion of firms having at least one woman on the board of directors increased to 78.2 percent, and the proportion of firms having more than one female member rose to 40.0 percent. Moreover, from this point on, women were present in all sectors of the economy and were no longer only concentrated in the retail and distribution sectors. This evolution can be explained by two main factors. First, we observe an increase in women in the corporations close to the Confederation, which were more inclined to promote gender equality. Indeed, in November 2013, the Federal Council announced that women should represent 30 percent of the board members of the firms owned by the Confederation, or close to it, by 2020.Footnote 86 In 2015, there were, for example, four women and six men on the board of directors of the Swiss Post, an organization wholly owned by the Swiss Confederation. The second factor that contributed to an increase in women among the boardrooms of large firms was the promotion of diversity management strategies among some multinational firms such as Nestlé (four women among fourteen board members in 2015), UBS (three women among eleven board members in 2015), and Novartis (three women among twelve board members in 2015). For instance, Peter Brabeck-Letmathe, chairman of the board of directors of Nestlé, and Paul Bulcke, CEO, insisted in a letter to the shareholders on referring to the firm’s “progress in diversity and gender balance,”Footnote 87 while the 2015 annual report of UBS, the largest Swiss bank, declared: “We have focused the majority of our effort in 2015 on gender diversity,” considering diversity as a “competitive strength.”Footnote 88 This kind of speech was typically in line with the “business case” argument, claiming that diversity is good for a business.

Compared with the previous decades, another striking change consists in the increase in foreign women among the largest Swiss enterprises, which resulted from the increasing internationalization of the firms from the end of the twentieth century. In 2015, 39 percent of the women sitting in the boardrooms were foreigners. As shown in Heemskerk and Fennema’s study, there was also an important increase in the share of foreign female directors on the board of the largest Dutch firms, but in a larger proportion when compared with male directors. This leads the authors to conclude that it was still very difficult for a Dutch female to reach a top position, and even more “because of the popularity of foreign females.”Footnote 89 In Switzerland, the proportion of foreigners among female directors was also slightly larger than the proportion of foreigners among male directors, but in a less important way.

Despite this progress, the corporate elite has remained a male bastion. In particular, women have been continuously largely excluded from the top positions in firms. Indeed, most of the women sitting on the boards of directors have never acceded to the presidency, apart from a few exceptions (one woman in 2010, and four in 2015). Likewise, women have remained globally excluded from the top executive positions, including for the most recent period (see Table 2). In 2015, there were only four women among the CEOs of the 110 largest Swiss firms: Susanne Ruoff (Swiss Post), Magdalena Martullo-Blocher (EMS Chemie), Jasmin Staiblin (Alpiq), and Suzanne Thoma (BKW Energie). These women showed very different profiles. The presence of Susanne Ruoff can be explained by the fact that the Swiss Post is a state-owned company, more inclined to apply gender equality (see earlier discussion). Magdalena Martullo-Blocher inherited the direction of Ems Chemie from her father, the well-known far-right politician Christoph Blocher, who in 2004 handed the family firm to his daughter and son when he was elected to the Federal Council. As for Jasmin Staiblin, a German citizen and the only foreigner among these female CEOs, she had been the head of ASEA Brown Boveri (ABB) (2006–2012) before her appointment in 2009 to the general direction of Alpiq. Finally, Suzanne Thoma was from August 2010 a member of the executive board of BKW, before her appointment in 2013 as the new CEO of the firm.

To conclude, we can say that the evolution of the position of women among the corporate elite at the beginning of the twenty-first century was mitigated. On the one hand, there had been a clear improvement when compared to the twentieth century. In 2015, three-quarters of the largest Swiss firms had at least one woman on their boards, and these firms encompassed almost all economic sectors. The female presence was no longer concentrated in family firms, as it was during the first half of the twentieth century, or in the very “feminine” retail and distribution sector, as was the case at the beginning of the 1980s. On the other hand, Switzerland was still clearly lagging behind other European countries, and women were still encountering glass ceilings, as they remained largely excluded from the leading positions in firms.

Conclusion

The aim of this research was to understand the historical and political factors that have contributed to the enduring exclusion of women from Swiss corporate boards. Contrary to a widespread view in the current debates on board diversity, “the roots of gender inequality are not found in the ‘inefficient’ use of women’s labour,” but rather in the inequalities of power based on sex.Footnote 90 When it comes to corporate elites, these inequalities are part of the gendered division of labor that was built up during nineteenth-century industrialization.

The present contribution has focused on the Swiss case, where the advance of women in the economic sphere has been especially slow in comparison to other Western countries. As I have shown, three main phases can be discerned in the long-term evolution of women’s presence among the 110 largest Swiss firms. During the greatest part of the twentieth century, women represented less than 1 percent of the corporate elite. At that time, corporate governance was dominated by family capitalism, which, interestingly, contributed both to the exclusion and to the (very limited) integration of women in the firms. On the one hand, family firms were clearly relying on a very patriarchal system, favoring the male members of the family. On the other hand, however, the very few women who could enter the boardrooms belonged to the families owning the firms. The second phase starts in the 1970s and heralds a progressive increase in the female presence, which had remained very low and stable during previous decades. Women finally obtained the right to vote and to be elected at the federal level in 1971, which gave a decisive impulse to change the role and place of women in Swiss society. The first women entering boardrooms in nonfamily firms were often political activists, which is consistent with the findings of Heemskerk and Fennema in the Dutch case. However, the process was different in the Swiss case, as these women entered companies belonging to the distribution and retailing companies in the private sector, rather than state-owned firms. In this sense, external pressures on Swiss corporate elites remained for a long time very weak, which contributes to explaining the late process of elite democratization. Real change happened only at the end of the twentieth century. The rapid economic globalization and internationalization of the Swiss economy contributed to weakening corporate elite cohesion, and Swiss and foreign women became more and more present in Swiss firms.

As board recruitment has tended to rely on a process of co-optation, the increase in women probably contributed—and will contribute in the future—to perpetuating the process. However, women were still hitting the glass ceiling regarding the top positions in the firm, as only 4 percent of them acceded to a chief executive position in 2015. Moreover, the few women who succeeded in breaking the glass ceiling were often confronted with strong criticisms, showing the enduring distinction made between the household and work and the role assigned to women. Thus, when Jasmin Staiblin, CEO of Alpiq and former CEO of ABB, took maternity leave in 2009, she was harshly criticized by Roger Köppel, a member of the Swiss People’s Party, who wrote in the Weltwoche: “No man in a similar high ranking position would be allowed, in such a precarious economic situation, to leave his firm for personal reasons.”Footnote 91

In the end, these women’s history testifies to a deeply conservative Switzerland, with several factors contributing to hinder the process of elite democratization. I have insisted on mentioning the importance of the role of the army in the elite recruitment process, as well as women’s extremely late access to the right to vote. The customary weak intervention of the state in the economy is another strong factor. Indeed, the state can promote the presence of women on boards of directors in two ways: by giving them seats in state-owned companies, as the Netherlands has done, and by introducing female quotas in public limited companies, as most Western countries have done. In Switzerland, the Federal Council waited until 2013 to introduce a quota of women on the boards of directors of the large firms close to the Confederation, and until December 2015 to propose a project of reform of legislation on companies limited by shares, aiming at 30 percent of women on the boards of directors and 20 percent on the executive boards by 2020.Footnote 92 The project was much less constraining than the French one, as it was formulated as a mere recommendation, and no sanctions were planned; it nevertheless provoked a general outcry within business circles. In June 2018, the National Council finally ratified by a small margin the Federal Council’s proposition.Footnote 93 Finally, another factor that probably contributed to Swiss backwardness lies in the fact that Switzerland is not a member of the European Union, so the different discussions that have taken place since 2006 at the European level in order to improve gender equalityFootnote 94 might have at best indirect, but no direct effects.

This contribution is a first attempt to recount the role and place of women on large Swiss firms’ corporate boards in a long-term perspective. It is only a starting point, and many further stimulating researches remain to be done. For instance, a systematic analysis of the profile of women who have acceded to the board of large firms in the recent period sounds promising, notably in order to compare their profile with that of the male elite. A more fine-grained analysis of the firms that these women represent also deserves more attention. Finally, it would be very interesting to integrate the findings on the Swiss case in cross-national comparisons, which calls for more studies adopting a historical perspective.