‘The challenges ahead for biodiversity conservation will require a better understanding of one species: our own’ (Saunders et al. Reference Saunders, Brook and Myers2006: 702)

Introduction

Despite the societal benefits provided by nature – ‘nature’s contribution to people’ (NCP) (Pascual et al. Reference Pascual, Balvanera, Díaz, Pataki, Roth and Stenseke2017) – natural systems within urban areas continue to be exploited and encroached upon by unprecedented urbanization, with environmental, social and socioeconomic costs (White et al. Reference White, Turpie and Letley2017). This indicates a plurality of perceptions and attitudes towards the importance of protecting urban nature and the ecosystem services it provides. Internationally, few studies have addressed the perceptions and values attached to nature, particularly in the Global South (Botzat et al. Reference Botzat, Fischer and Kowarik2016). The lack of understanding of the values of urban nature in sub-Saharan Africa, and Africa more broadly, is a barrier to the provision of sustainable ecosystem services from urban green spaces (Wangai et al. Reference Wangai, Burkhard and Müller2016, du Toit et al. Reference du Toit, Cilliers, Dallimer, Goddard, Guenat and Cornelius2018, Lindley et al. Reference Lindley, Pauleit, Yeshitela, Cilliers and Shackleton2018). Despite the unprecedented urbanization in Africa, biodiversity and ecosystem services provide a foundation for green infrastructure to serve increasing human populations (Güneralp et al. Reference Güneralp, Lwasa, Masundire, Parnell and Seto2017). However, fragmented governance, limited knowledge and a focus on open space beautification limit the potential of green infrastructure and the effective incorporation thereof into city decision-making (Herslund et al. Reference Herslund, Backhaus, Fryd, Jørgensen, Jensen and Limbumba2018).

In informal settlements in Africa, residents, due to socioeconomic circumstances, connect and rely on natural ecosystems for survival, as opposed to recreation (Adegun Reference Adegun2017). In South Africa, studies related to urban green spaces have addressed green infrastructure collectively, incorporating private and public gardens, street trees, riparian zones, wetlands and community-based gardens (Cilliers et al. Reference Cilliers, Cilliers, Lubbe and Siebert2013, Shackleton et al. Reference Shackleton, Blair, De Lacy, Kaoma, Mugwagwa, Dalu and Walton2018). If natural assets are valued on a par with other city infrastructure, ecosystem service provision, socioeconomic upliftment and employment opportunities will be enhanced (Schäffler & Swilling Reference Schäffler and Swilling2013). While there is increasing recognition of the importance of green infrastructure and nature-based solutions for enhancing urban resilience (Cilliers Reference Cilliers2019), there has been little explicit focus on the perceptions and relational values of urban natural open space systems: land specifically excluded from most development to protect the provision of ecosystem services, often without formal protection. Recognition of this knowledge gap in the values and perceptions of nature (Botzat et al. Reference Botzat, Fischer and Kowarik2016) is reflected in calls by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) to understand the multiple values of nature (Pascual et al. Reference Pascual, Balvanera, Díaz, Pataki, Roth and Stenseke2017). The IPBES framing of ecosystem services as NCP reflects both the benefits and the ‘occasional negative contributions, losses or detriments’ related to nature (Pascual et al. Reference Pascual, Balvanera, Díaz, Pataki, Roth and Stenseke2017: 9). ‘Nature’ encompasses both biodiversity and ecosystem services; biodiversity underpins numerous ecosystem services, such as habitat, medicinal harvesting, identity and other cultural services, and these may influence relational values with nature. Stakeholder knowledge systems create and can maintain biodiversity by ensuring the protection thereof, which allows for the option value, in terms of the future uses and benefits of biodiversity, to be retained (Díaz et al. Reference Díaz, Demissew, Carabias, Joly, Lonsdale and Ash2015).

Perceptions of nature, in term of benefits (ecosystem services) and nuisances (disservices), are complex constructs (Fischer & Young Reference Fischer and Young2007) shaped by sociodemographics; by interrelated socioeconomic, spatial, temporal and political contexts; and by local cultures, individual values and norms (Döhren & Haase Reference Döhren and Haase2015, Chan et al. Reference Chan, Balvanera, Benessaiah, Chapman, Díaz and Gómez-Baggethun2016, Díaz et al. Reference Díaz, Pascual, Stenseke, Martín-López, Watson, Molnár and Larigauderie2018, Constant & Taylor Reference Constant and Taylor2020, Shackleton et al. Reference Shackleton, Cilliers, Davoren and du Toit2021). Subjective notions of social equity and fairness, as well as of power and relations (Pascual et al. Reference Pascual, Phelps, Garmendia, Brown, Corbera and Martin2014), are also influenced by – and influence – the management of open spaces (Fischer & Young Reference Fischer and Young2007). Interactions and experiences of nature change over time; meaningful connections support positive perceptions, while poor-quality open space may perpetuate the extinction of experience (Saunders et al. Reference Saunders, Brook and Myers2006, du Toit et al. Reference du Toit, Cilliers, Dallimer, Goddard, Guenat and Cornelius2018). In Africa, urban natural areas have often been associated with ecosystem disservices related to safety (Cilliers et al. Reference Cilliers, Cilliers, Lubbe and Siebert2013), while in the Global North the value and acceptance of natural landscapes has increased (Hoyle Reference Hoyle2020). Martín-López et al. (Reference Martín-López, Iniesta-Arandia, García-Llorente, Palomo, Casado-Arzuaga and Del Amo2012) found females in Spain were more aware of the ecosystem services provided by nature due to societal gender-differentiated roles, while in Durban (South Africa) females made less use of green spaces due to safety fears (Pillay & Pahlad Reference Pillay and Pahlad2014). The socioeconomic status associated with higher income and education is typically correlated with a higher level of environmental concern (Bronfman et al. Reference Bronfman, Cisternas, López-Vázquez, Maza and Oyanedel2015), attributed to increased understanding and exposure to environmental information; however, empirical evidence in this regard is not necessarily consistent (Olli et al. Reference Olli, Grendstad and Wollebaek2001). Although sociodemographic variables may be related to environmental concern, the directions and correlations vary across studies; consequently, there is no comprehensive model from which generalizations can be drawn (Saunders et al. Reference Saunders, Brook and Myers2006, Lui & Mu Reference Liu and Mu2016).

This study contributes understanding within the urban African context of how residents value and connect with natural open space systems in urban areas. The Nelson Mandela Bay Municipality (NMBM), situated at the convergence of two globally recognized biodiversity hotspots in South Africa, is used as a case study. The objectives were: (1) to identify ecosystem services and disservices associated with the city’s natural open space system, and the reasons thereof, by exploring the relational values of nature held by a diverse socioeconomic spectrum of urban residents; and (2) to identify priorities for protecting the natural open space system by enhancing the benefits and minimizing ecosystem disservices. Understanding context-specific perceptions of urban nature can contribute to improved consideration of ecosystem services provided by nature in urban planning, enhancing access to nature and ecosystem services, and to improved city management (Aalto & Ernstson Reference Aalto and Ernstson2017). While natural resources are increasingly threatened, windows of opportunity persist to protect the remaining important urban natural assets in Africa if cities are to be directed towards a sustainable trajectory (White et al. Reference White, Turpie and Letley2017).

Methods

Introduction to the case study

The NMBM in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa is c. 1959 km2 in area, with a population of c. 1.27 million (NMBM 2019). Colonial and apartheid-based planning in the city has spatially manifested in race-related socioeconomic gradients of disparity (NMBM 2019). Poor economic growth, a young population, high unemployment and dependency on municipal indigent subsidies, together with corruption and lacklustre leadership, have exacerbated the municipality’s inability to maintain and provide services, and to move beyond a welfare state (Cilliers & Aucoin Reference Cilliers and Aucoin2016, NMBM 2019). Many township residents live in government-provided houses even though they may be involved in part-time, often informal employment. ‘Townships’ refer to racially segregated areas created under the system of apartheid, typically located on the periphery of towns with poorer standards of engineering services and less access to social facilities and amenities, such as schools, libraries and healthcare facilities. The natural open space plan for the city, referred to as the Nelson Mandela Metropolitan Open Space System (NM MOSS), was developed in a systematic conservation planning process (Margules & Pressey Reference Margules and Pressey2000). The NM MOSS includes mostly undeveloped natural and semi-natural areas, mainly covered with indigenous vegetation, although not necessarily pristine ecosystems. Within the NM MOSS, there are several priority conservation areas, most of which are linked to municipal nature reserves.

Given the extensive size of the NMBM, an area within the city that reflects its diverse socioeconomic characteristics was selected to help understand residents’ perceptions of natural open space systems. Consequently, an area near one of the NM MOSS priority sites – the Swartkops–Aloes Reserve Complex, comprising the critical conservation areas of the Swartkops and Aloes Nature Reserves and the Swartkops Estuary – was selected. The area has a diverse socioeconomic and ethnic spectrum of communities, ranging from middle to upper income with formal housing, to low income and high levels of poverty with informal housing (Fig. 1). The predominant reserve vegetation is impenetrable subtropical thicket. Motherwell Township, originally developed in the 1980s, abuts the Swartkops Nature Reserve. The Aloes Nature Reserve is situated on the periphery of the more recently established (1990s) Wells Estate Township and the historically white, more affluent residential suburbs of Bluewater Bay and Amsterdamhoek.

Fig. 1. Location of study sites adjacent to the Swartkops–Aloes Reserve Complex within the Nelson Mandela Bay Municipality.

Typical of most townships, Wells Estate and Motherwell reflect the formal and informal characteristics of residential and economic opportunities. Wells Estate and the more recently developed parts of Motherwell are particularly lacking in terms of essential social infrastructure, such as schools, clinics and police stations. Swartkops residential area, on the southern side of the Aloes Nature Reserve, consists of formal housing, including a small well-established community of c. 35 households, referred to as the Aloes Brickfields Community, living in brick houses with rudimentary services (communal water standpipes and no waterborne sewerage). Further west along the Swartkops River is a small residential enclave, Redhouse. Swartkops and Redhouse were established in the late 1800s, while Amsterdamhoek and Bluewater Bay were developed in the 1950s and 1970s, respectively. To the south of the estuary is KwaZakhele Township, established in 1950s at the height of apartheid (Prevost & Cherry Reference Prevost and Cherry2017). KwaZakhele abuts a highly disturbed and polluted natural pan, Pond 6, on the floodplain of the estuary. The natural pan is proposed for inclusion in a campaign to declare the estuary and the adjoining nature reserves as a Ramsar international wetland.

Methodology

We used a two-part questionnaire to explore community perceptions of natural open space. The first part included descriptive (quantitative) demographic and socioeconomic data, and the second part of the questionnaire consisted of semi-structured (qualitative) interviews with individual community members on nature and the use of natural open spaces in the area (Appendix S1, available online).

Interviews allowed deliberation on individuals’ perceptions and experiences of a phenomenon, contributing to rich data collection (Ryan et al. Reference Ryan, Coughlan and Cronin2009) and understanding of the values placed on ecosystem services (Scholte et al. Reference Scholte, van Teeffelen and Verburg2015). The intention of the interviews was to explore and understand participants’ ‘mental constructs’ of nature and ecosystem services and the diversity of reasons for attitudes and perceptions (Fischer & Young Reference Fischer and Young2007: 271), facilitating consideration of the relational values people have with nature.

Data collection

Interview participants (n = 40) were selected using a combination of purposive and snowball sampling approaches. Google Earth and Geographic Information System (GIS) maps available from the municipality were used to ensure residential sites were identified based on their proximity to the NM MOSS. The only selection criterion required was the willingness to participate. The numbers of respondents interviewed for the eight residential areas were: Aloes Community: two; Amsterdamhoek: four; Bluewater Bay: nine; KwaZakhele: five; Motherwell: ten; Redhouse: two; Swartkops: three; and Wells Estate: five. The sample size was estimated from proportional representation of the different socioeconomic areas and confirmed when the saturation point was reached where no new issues or additional insights were raised by the respondents (36th participant from all of the interviews). The ratio of purposive to snowball sampling was 15 (37.5%):25 (62.5%). Purposive sampling was used for six of the ten respondents in Motherwell; for four of the five respondents in Wells Estate; and for all five respondents from KwaZakhele, who lived near to the wetland. Purposive sampling was initiated in Motherwell by knocking on a door of a property abutting the NM MOSS boundary, followed by interviewing an additional resident located c. 200 m away, also located on the NM MOSS boundary; thereafter, other residents not directly adjacent to the MOSS, but no less than 600 m away, were interviewed. A similar approach was followed for Wells Estate and KwaZakhele. As suburban residents tend to be less inclined to engage in interviews with an unknown person, a snowball approach, where respondents interviewed provided names and contact details of other potential participants, was adopted for the suburbs and the Aloes community, which could not have been reached through purposive sampling.

Interview questions related to the respondents’ greatest daily concerns with respect to their residential areas; the role nature plays in respondents’ lives; if and how nature was used, and the associated likes and dislikes; and knowledge of any municipal planning processes (Appendix S1). Emphasis was placed on understanding the reasons for responses and how real and perceived access to natural open space influenced responses. Understanding the socioeconomic and service delivery challenges characteristic of many areas in South Africa facilitated the contextualization of individual values of nature.

Interviews were undertaken from September to December 2019, in or outside of participants’ homes or their place of employment if they preferred. Interviews lasted 15–60 minutes and were recorded with the permission of the interviewees, and notes were taken. Interviews were conducted in English, apart from where respondents preferred to speak in isiXhosa, when an interpreter was used.

Data analyses

All interviews were transcribed, and thematic content analysis of the data and observations of the area was undertaken manually (Guest et al. Reference Guest, MacQueen and Namey2012). Using emergent codes to identify themes manually, thematic analysis is useful in capturing complexities in meaning (Ryan et al. Reference Ryan, Coughlan and Cronin2009), particularly where inductive analyses of interview responses is necessary. Emerging themes were grouped as follows: (1) benefits – nature as a resource for supporting livelihoods and lifestyles and community outreach and employment opportunities; (2) ecosystem disservices – personal safety and health and aesthetic concerns; and (3) perspectives on management of natural open spaces – lack of political accountability and municipal planning and priorities for the natural open space system. Implicit and explicit references to ecosystem services and disservices, inferred from the interviewees’ responses and particularly related to the ‘role of nature in communities’, ‘how nature is used’ and the ‘dislikes of nature’, were coded according to the IPBES categorization of NCP (i.e., the overlapping groups of regulating, material and non-material contributions) (Díaz et al. Reference Díaz, Pascual, Stenseke, Martín-López, Watson, Molnár and Larigauderie2018). Demographic data were summarized using Microsoft Excel and analysed for associations between demographic and socioeconomic variables and perceptions of nature. Given the qualitative nature of the research, no statistical analyses were conducted.

Results

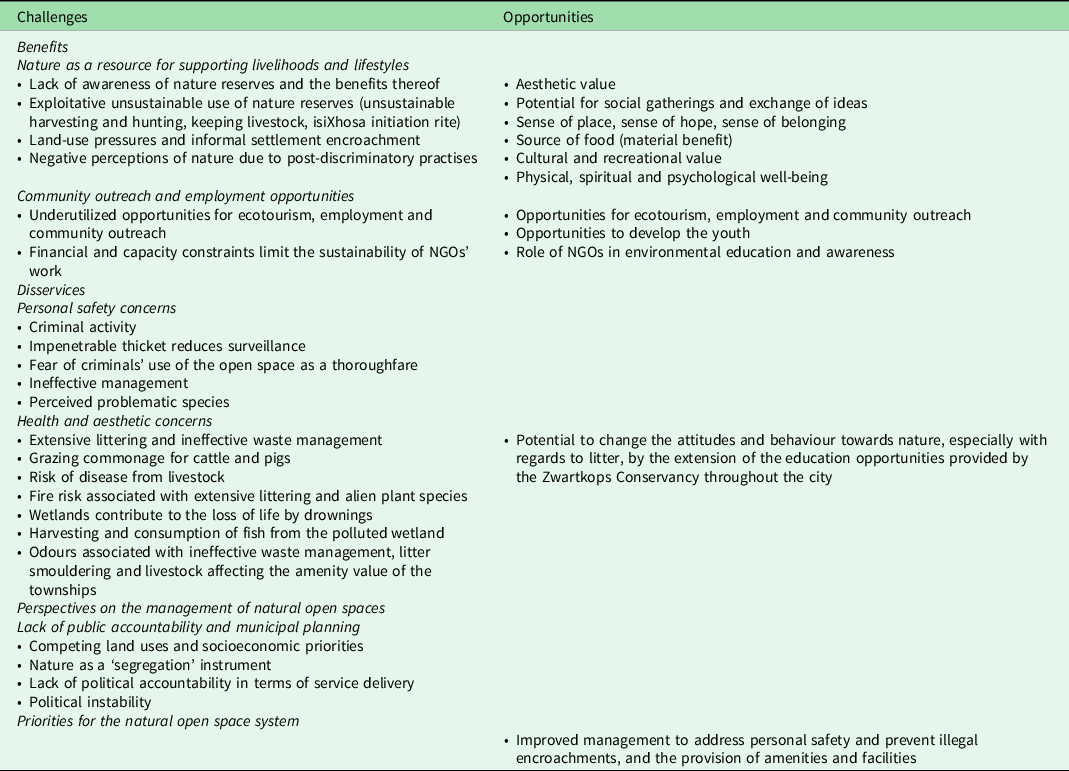

Emerging themes related to nature as a resource (benefit) and nuisance and to perspectives on management of natural open space systems (Table 1 & Appendix S2). Empirical evidence related to the age, gender and socioeconomic data and nature perceptions could not be ascertained from the sample size; however, the results were useful for contextualizing the responses received (Table 2). Across the demographic and socioeconomic spectrum, the lack of accountability and political instability were shared by all respondents. Our research did not reveal gender-differentiated roles with regards to nature. General safety concerns were shared across genders and the socioeconomic spectrum, and few interviewees were directly dependent on the natural environment for survival. The sample size did not support any correlations between higher income and education and increased concern for the environment.

Table 1. Interrelated challenges and opportunities related to the theme of nature being both a resource (benefit) and a nuisance identified from the interviews.

NGO = non-governmental organization.

Table 2. Summary of the background socioeconomic and demographic data of the survey sample (n = 40).

a In South Africa, the use of the term ‘coloured’ is a recognized racial category.

Benefits

Nature as a resource for supporting livelihoods and lifestyles

All respondents, apart from one from Wells Estate and one from KwaZakhele, expressed an implicit or explicit appreciation of nature for its contribution to human well-being for various material, non-material and regulating benefits, some of which are overlapping across the NCP groups (Table 3). Diverse perceptions of nature, as a benefit (positive NCP) and/or a nuisance (negative NCP) by different respondents, were attributed to individual and/or community relational and instrumental values with nature (Table 4). Past discriminatory legislation impacted on perceptions. Most interviewees (95%) referred overtly to the non-material services (relational benefits) provided by nature, particularly for various forms of recreation, spiritual inspiration and education (Table 3). A sangoma (traditional healer) from Motherwell used the reserves for medicinal harvesting. Due to safety fears, sangomas collected together to ensure that they could continue to support their livelihoods and retain a sense of place related to the cultural significance of their traditional practice for human well-being. Other material uses, inferred from concerns expressed across the socioeconomic continuum, related to the exploitative, illegal use of the reserves (Table 3).

Table 3. Examples of nature’s contribution to people (NCP) – both positive and negative – identified from the community interviews and observations. Categories based on Díaz et al. (Reference Díaz, Pascual, Stenseke, Martín-López, Watson, Molnár and Larigauderie2018). The positive NCP examples are indicated in italics; non-italic font depicts those NCP examples that are positive, but they are also negative due to concerns of exploitation and unsustainable resource use. This is distinct from the ‘fire hazard’ associated with alien plant species, which is solely negative.

Table 4. Summary of instrumental and relational values of the natural open space system identified from the community interviews and observations.a

a Intrinsic values identified included habitat (for maintaining biodiversity).

Several material and non-material benefits, such as food obtained through hunting and medicinal harvesting as a means of survival and/or socioeconomic upliftment for some residents in the townships, were considered unsustainable by other respondents: one respondent stated ‘… it’s not sustainable … they come with picks … there is good stuff they are taking and it’s just destruction …’. For some community members, hunting was considered as a form of recreation (non-material benefit), with one stating ‘… it’s just mischievous, naughtiness …’, as opposed to a means of obtaining food (material benefit) for survival. Loss of nature, and the associated benefits, was perceived to be caused by illegal encroachments on the open space system for cultivation, additional housing structures, grazing commonage, the felling and burning of vegetation required for the traditional isiXhosa initiation rite into (male) adulthood, and informal settlement. The latter was considered to signify a need for land, attributed to political instability within the coalition local government. Continued encroachment would reduce the availability of medicinal plants, threatening the sangomas’ livelihoods and the well-being of many people: ‘… once you have settlements encroaching on the MOSS the medicinal plants are destroyed … one never really plants those things, they grow in nature, and often they are only for this area, once it’s gone you also kill many other things …’.

Several of the respondents from Bluewater Bay were not aware of the reserves; one respondent from Swartkops attributed this to the fact that the education activities of the Zwartkops Conservancy – a longstanding environmental non-governmental organization that takes township scholars into the Swartkops–Aloes Reserve Complex for environmental education – did not include Bluewater Bay. Awareness of the reserves in Motherwell, evident from the interviews, was attributed to the work of the Zwartkops Conservancy.

Community outreach and employment opportunities

Although Zwartkops Conservancy conservation initiatives provided employment opportunities, the potential of the Swartkops–Aloes Reserve Complex for ecotourism and community upliftment was underutilized due to poor reserve management. The municipality was criticized for its lack of financial support for the Zwartkops Conservancy, who were said to be doing the work of the local government, and for hindering its innovative conservation proposals.

Disservices

Personal safety concerns

The role of nature in supporting lifestyles and livelihoods was impacted on by real and perceived safety concerns (Table 1) inhibiting the optimization of non-material benefits, such as physical, spiritual and psychological well-being. All respondents expressed the fear of crime in the nature reserves, particularly if alone, because the impenetrable vegetation there limits surveillance. Some residents felt threatened by criminals’ use of the open space as a thoroughfare. Crime – though not necessarily limited to the natural open space system – was the greatest daily concern for all respondents, apart from those in Redhouse and Aloes. Many respondents ascribed the crime to poor municipal management. These concerns were increased by the fact that both reserves were unfenced and no entrance fee was required. Criminals capitalized on the open access and lack of management, which reduced voluntary visitors’ access and societal benefits. For several residents, access was considered to be prohibited due to the perception that an (unaffordable) nature reserve entrance fee was payable, which would guarantee visitors’ safety and without which criminal activity would increase. Consequently, it was considered that ‘… people become home-bound …’ despite their proximity to the reserves.

Health and aesthetic concerns

The respondents were distressed by health and aesthetic issues (Table 1) and ‘problematic’ species, such as monkeys and snakes, which were perceived as threatening to residents and their livestock. Ineffective waste management was attributed to the actions of residents and inadequate service from the municipality. The natural open space, the wetlands and many of the urban parks were used extensively for (illegal) dumping of household refuse, building rubble and domestic animals and livestock by the broader community, particularly in the townships. A Zwartkops Conservancy educator who lives in the township wanted to extend their education activities throughout the city in an endeavour to change city attitudes and behaviours towards nature, especially with regards to litter. The poorly managed waste transfer station opposite the entrance to the Aloes Nature Reserve was an aesthetic concern that discouraged the public use thereof and attracted potential criminal activity. Excessive dumping, together with alien vegetation infestation and the (illegal) informal structures, exacerbated fire risks.

Perspectives on the management of natural open spaces

Lack of political accountability and municipal planning

Most township respondents were unaware of the municipality’s integrated development planning process – a strategic plan based on community participation that aligns municipal plans and projects with budgets and resources for implementation, including maintenance, aimed at addressing community priorities (South Africa 2000). All participants, implicitly or explicitly, indicated that local government was ‘failing the community’. Lack of political accountability and ineffective service delivery were expressed by interviewees across the socioeconomic range, particularly related to ineffective waste management and the maintenance and provision of engineering and social infrastructure. One respondent stated ‘… there is nothing – no provision for schools, business or churches … the settlements are going further away from economic activities, with no provision for transport …’; this was emphasized by the statement that ‘… local government is an impediment to progress …’. Complex multilayered systems and procedures, characteristic of municipal bureaucracies, were considered to impede progress and innovative community solutions. Socioeconomic disparities between the townships and the other areas were attributed to an inability to redress apartheid legacies, and the notion of nature being used as a means of segregation underscored the complexities of conservation efforts and competing land uses.

Priorities for the natural open space system

As access to the ecosystem services is inhibited by the safety and encroachment concerns, improved management of the open space system was identified as a priority. Several township respondents expressed a need for tree planting in the urban parks and a safe place for children to play ‘… to address the social ills in the townships …’, suggesting an implicit understanding of the benefits of nature. The expressed need for amenities (e.g., benches and picnic sites) in the nature reserves and around the wetland indicated the importance of providing quality open space amenities, particularly in the socioeconomically depressed townships.

Discussion

We identified ecosystem services and disservices based on exploring complex relational values of the city’s natural open space system. Positive and negative NCPs were shaped by real and perceived access, impacted by individual and societal use and management of the open space. Priorities for the city’s natural open space system, aimed at enhancing the benefits and minimizing the real and perceived disservices, require collaborative management intervention.

Dependence on nature

In South Africa and elsewhere, many urban dwellers are dependent on urban open spaces for provisioning natural resources, such as water, fuel and food (du Toit et al. Reference du Toit, Cilliers, Dallimer, Goddard, Guenat and Cornelius2018); for livestock (Shackleton et al. Reference Shackleton, Guild, Bromham, Impey, Jarrett, Ngubane and Steijl2017a); and for urban foraging for numerous benefits (Shackleton et al. Reference Shackleton, Hurley, Dahlberg, Emery and Nagendra2017b). Although poverty is often a significant determinant of natural resource dependency, some urban communities in South Africa have reduced dependency due to the free/subsidized services for low-income households provided by the government (Balbi et al. Reference Balbi, Selomane, Sitas, Blanchard, Kotzee, O’Farrell and Villa2019). It cannot be established whether the exploitative uses identified from this study, which appear to be normalized behaviours, are part of individual survival strategies. Apart from a traditional healer, the respondents in this study were not directly dependent on the natural resources for economic livelihoods, and lower-income households did not indicate an increased reliance on the natural open space system. This may be attributed to government grants and free access to some services. This non-reliance on provisioning services from nature differs from what has been found in other African cities (du Toit et al. Reference du Toit, Cilliers, Dallimer, Goddard, Guenat and Cornelius2018; discussed further below), and it underscores the need to avoid generalizations and adopt more nuanced approaches when communicating in collective terms about African cities.

Disconnection of urban societies from the natural environment due to less obvious, tangible benefits (Scholte et al. Reference Scholte, van Teeffelen and Verburg2015) may contribute to the perceived tolerance of the degradation and loss of certain ecosystem services (Kumar & Kumar Reference Kumar and Kumar2008), such as the extensive littering in the natural open space system. Environmental deterioration caused by pollution, bush burning and poor waste management are not unique to Africa (Nagendra & Ostrom Reference Nagendra and Ostrom2014), but often is a symptom of insufficient access to, or lack of, municipal services, such as ineffective solid waste management, reflecting the inadequacies of the local government.

Contested nature of conservation

Aesthetic, health and safety concerns detract from the existing and potential benefits of nature being realized and indicate how (mis)management impacts – directly and indirectly – on access to the reserves, outweighing the benefits derived from nature, such as ecotourism and associated employment opportunities. The work of the Zwartkops Conservancy has indirectly enhanced access to natural resources through increased awareness, particularly in the township, inspiring future ambassadors for the natural environment (Collier Reference Collier2016). However, unless nature is of societal relevance and the nature reserves are recognized as community assets, the NM MOSS will not be collectively safeguarded.

Contrasting opinions of nature can lead to and exacerbate social conflicts (Döhren & Haase Reference Döhren and Haase2015), particularly where open space is viewed as a segregation buffer between socioeconomic classes and where the use of perceived vacant land is contested. Non-material benefits (cultural services) may be better understood in terms of relational values (Chan et al. Reference Chan, Balvanera, Benessaiah, Chapman, Díaz and Gómez-Baggethun2016). Understanding drivers of individual and societal behaviour found in this case study, as well as those of relational justice and power imbalances, is central to enhancing management decisions and nurturing appropriate stewardship options in complex contexts, where stakeholders have diverse interests and perceptions (Chan et al. Reference Chan, Balvanera, Benessaiah, Chapman, Díaz and Gómez-Baggethun2016, Himes & Muraca Reference Himes and Muraca2018, Muradian & Pascual Reference Muradian and Pascual2018, Stenseke Reference Stenseke2018, West et al. Reference West, Haider, Masterson, Enqvist, Svedin and Tengö2018). The case study indicates that, from a community perspective, the elements that are pivotal for stewardship success – care, knowledge and agency and the ability to engage collectively to affect change (Enqvist et al. Reference Enqvist, West, Masterson, Haider, Svedin and Tengö2018) – do exist, but the success thereof requires improved collaboration, champions to drive the cause and greater involvement from the municipality in terms of financial and management commitment.

Ownership of the natural open space system

Limited recognition of the biodiversity of the study area – a global biodiversity hotspot with the unique convergence of five biomes in one city – is reflected in the apparent limited ownership of the natural open space system. Contrary to other urban ecosystem service studies in sub-Saharan Africa, where local communities were dependent on regulating and provisioning services for resilience and livelihoods (du Toit et al. Reference du Toit, Cilliers, Dallimer, Goddard, Guenat and Cornelius2018, Lindley et al. Reference Lindley, Pauleit, Yeshitela, Cilliers and Shackleton2018), provisioning and regulating services were not identified to be of overriding significance to the respondents in this study. The latter is attributed to the situation of nature reserves at higher elevations, beyond the floodplain, with only a few residents abutting the Swartkops river in Amsterdamhoek, Redhouse and Aloes being vulnerable to flooding.

Respondents’ intuitive reference to urban parks as opposed to the nature reserves when asked about their experiences, likes and dislikes of nature could be an indication of the human–nature relationships and the preference for active recreation areas for various reasons. Reduced municipal budgets for both active and passive recreation in the city are reflected in the inadequate maintenance, leading to overgrown open spaces that attract antisocial behaviour, including dumping, crime and land invasion (NMBM 2019), compromising residential amenity and contributing to negative perceptions. Nature is not only a physical experience, but also a social heterogeneous construction with political associations (Aalto & Ernstson Reference Aalto and Ernstson2017, Tozer et al. Reference Tozer, Hörschelmann, Anguelovski, Bulkeley and Lazov2020). Lack of awareness and/or an apparent absence of positive relationships with nature for certain respondents may be attributed to past restricted access to natural resources (Wynberg Reference Wynberg2002), public or common rights being historically non-existent (Colding et al. Reference Colding, Barthel, Bendt, Snep, van der Knaap and Ernstson2013), structural and cultural inequities and socioeconomic challenges (Tozer et al. Reference Tozer, Hörschelmann, Anguelovski, Bulkeley and Lazov2020). Government’s failure to redress socioeconomic disparities influences perceptions of green space and how natural resources are valued and conserved (du Toit et al. Reference du Toit, Cilliers, Dallimer, Goddard, Guenat and Cornelius2018, Venter et al. Reference Venter, Shackleton, Van Staden, Selomane and Masterson2020). This could be why residents, in an endeavour to improve their socioeconomic circumstances, trade off ecosystem services within the nature reserves by, for example, encroaching on them for urban agriculture, animal husbandry and the felling and burning of vegetation.

Despite the dire socioeconomic circumstances experienced in many cities in the Global South, there are success stories related to natural open spaces. ‘Princess Vlei’ – a degraded urban wetland in an oppressed, marginalized community in Cape Town that had been neglected by past management – was rehabilitated by extensive civic involvement, with social and ecological benefits (Colding et al. Reference Colding, Barthel, Bendt, Snep, van der Knaap and Ernstson2013). Community values, articulated in terms of historical and political processes, were instrumental in understanding nature as a social practice (Ernstson & Sörlin Reference Ernstson and Sörlin2013) and facilitating successful stewardship (Aalto & Ernstson Reference Aalto and Ernstson2017). Environmental place-making – a process influenced by power, inequality and social dynamics, where diverse communities continually construct meaning and attach value to nature – can transform human–nature relationships, can assist in the realization of the benefits provided by natural open space systems and can shape collective stewardship action and cooperative management interventions (Sen & Nagendra Reference Sen and Nagendra2020). Without place-making, areas are more susceptible to encroachment and resulting land cover changes and loss of ecosystem services.

Institutional challenges and interventions

Potential access to and enjoyment of the reserves will be increased by the employment of rangers to patrol and manage the areas, the effective clearing of invasive species, the maintenance of existing engineering infrastructure, the provision of social infrastructure and effective waste management. Such measures would reduce the communities’ disillusionment related to political accountability and contribute to increasing the societal recognition, awareness and understanding of the role of nature. Limited financial and administrative resources inhibit the ability of city governments to effectively maintain urban commons. Stakeholder engagement and effective partnerships are therefore pivotal if city management is to ensure the ecosystem services provided by the natural open space system are to be protected and the ecosystem disservices minimized (Nagendra & Ostrom Reference Nagendra and Ostrom2014).

The sustainability of the natural open space system is also dependent on resolving competing land-use pressures on urban land perceived to be vacant. These include land requirements for grazing commonage, residential expansion and cultural purposes, such as the isiXhosa initiation rite, and medicinal harvesting, which we show to be of cultural, spiritual and socioeconomic importance for residents. The exposure to nature experienced in the initiation process can instil and retain a lifelong sense of significance for human–nature connectedness (Cocks et al. Reference Cocks, Alexander, Mogano and Vetter2016). City planning agendas need to prioritize the notion of people in nature and recognize that the environment is intertwined with – and underpins – sustainable development, and that different people unequally benefit from – or are burdened by – land-use decision-making processes (Leach et al. Reference Leach, Reyers, Bai, Brondizio, Cook and Díaz2018). Innovative management and investment solutions are needed that retain the multifunctionality of ecosystems and the relationships between different ecosystem services (Zari Reference Zari2018, Zari & Hecht Reference Zari and Hecht2020). Complex city dynamics, such as rising inequities and social conflicts related to accessing ecosystem services (Bennett et al. Reference Bennett, Cramer, Begossi, Cundill, Díaz and Egoh2015) and the contested nature of how best to utilize limited urban space (Ernstson & Sörlin Reference Ernstson and Sörlin2013), impact negatively on cooperation around shared resources and stewardship options (Hamann et al. Reference Hamann, Berry, Chaigneau, Curry, Heilmayr, Henriksson and Hentati-Sundberg2018). Multifunctional landscapes that allow for multiple objectives – incorporating conservation, recreation and a diverse range of sustainable resource uses (Ros-Cuéllar et al. Reference Ros-Cuéllar, Porter-Bolland and Bonilla-Moheno2019) – provide feasible alternatives for advocating for the ‘people in nature’ concept where, with collaborative stakeholder engagement, win–win situations with ecological and socioeconomic benefits can be achieved.

Conclusion

We endeavoured to understand the nuanced positive and negative contributions of an urban natural open space system, located within an important global biodiversity hotspot, to individuals in terms of their daily lives. While most urban ecosystem service studies emphasize the urban resilience role of green infrastructure, we focused on perceived values of nature, especially those framed as relational values. The study contributes to the dearth of local case studies on perceptions of urban nature in the Global South and addresses calls by the IPBES to understand the relational values of NCP (Pascual et al. Reference Pascual, Balvanera, Díaz, Pataki, Roth and Stenseke2017).

The qualitative interviews underscore the complexities of understanding perceptions of nature, the plurality of values and the reasons for these, which are pivotal to developing effective context-specific strategies for maintaining the ecosystem service benefits provided by natural open space systems and for informing potential trade-off decisions (Chan et al. Reference Chan, Balvanera, Benessaiah, Chapman, Díaz and Gómez-Baggethun2016). Management of the natural open space system has influenced access to ecosystem services – directly and indirectly – and impacted upon the experience of ecosystem disservices. Where the role of ’green infrastructure’ in terms of urban resilience and citywide benefits has been undervalued in city planning (Cilliers Reference Cilliers2019), understanding societal values of natural open spaces may sensitize city decision-makers to community needs, facilitating improved decision-making.

Despite the implicit recognition of ecosystem services, some individuals and groups remain disconnected from the natural open space system and the benefits nature provides. Designing ecosystem-based multifunctional landscapes requires the consideration of the diverse activities and needs of different stakeholders (Zari Reference Zari2018) and the range of NCPs (positive and negative) provided by natural open space systems. Stewardship can facilitate stakeholder collaboration while allowing for different uses and perceptions (Enqvist et al. Reference Enqvist, West, Masterson, Haider, Svedin and Tengö2018), enhancing cohesion between diverse communities (Muradian & Pascual Reference Muradian and Pascual2018) and integrating scientific and local traditional knowledge (Chan et al. Reference Chan, Balvanera, Benessaiah, Chapman, Díaz and Gómez-Baggethun2016).

Unprecedented urbanization in Africa, where much of the large-scale infrastructure investment is yet to be expanded, threatens the remaining biodiversity and societal benefits provided by natural ecosystems. This study, focused on a global biodiversity hotspot in Africa, identifies opportunities for how to incorporate and catalyse stewardship for natural open spaces and contextually appropriate interventions that could be employed in other African cities. As culture, environmental knowledge and societal behaviour change over time (Tyrväinen et al. Reference Tyrväinen, Mäkinen and Schipperijn2007), the methodology followed should be viewed as a part of an ongoing process of exploring the social constructions and values of nature and ecosystem services in order to enhance city decision-making.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0376892921000345.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge all our interviewees for their openness and time and the independent reviewers and the editor for their valuable input on an earlier draft.

Financial support

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. The research was privately funded by the corresponding author.

Author contributions

NW conceived the original paper and undertook the interviews. NS, KJE and POF all contributed to the manuscript.

Conflict of interest

None.

Ethical standards

The study proposal was approved by the Research Ethics Committee of Stellenbosch University (Project Number 9804). Participants were informed of their right to refuse to answer any questions and to withdraw from participation at any time. Informed consent was obtained and anonymity and confidentiality were guaranteed. Following a brief explanation of the study, all interviewees signed the informed consent form before the interview commenced. The sampling design for participants together with the informed consent form, information sheet and questionnaire were approved by the Ethics Committee. The informed consent form, information sheet and questionnaire were translated into isiXhosa for the interviewees who preferred to be interviewed in their home language (Appendix S1).