Introduction

Severe mental illnesses (SMI) include a cluster of mental disorders, such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, that cause serious functional limitations interfering with major life activities like education, work and social relationships (Cabassa, Reference Cabassa2023). Almost 40 million persons were estimated to live with bipolar disorders and over 23 million with schizophrenia in 2019 worldwide (GBD 2019 Mental Disorders Collaborators, 2022). For these individuals, research consistently shows an excess mortality compared to the general population, with a gap that is seemingly widening (Correll et al., Reference Correll, Solmi, Croatto, Schneider, Rohani-Montez, Fairley, Smith, Bitter, Gorwood, Taipale and Tiihonen2022; Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Kisely and Pais2010; Thornicroft, Reference Thornicroft2011); life expectancy is 15–20 years shorter (Coldefy and Gandré, Reference Coldefy and Gandré2018; Nordentoft et al., Reference Nordentoft, Wahlbeck, Hällgren, Westman, Ösby, Alinaghizadeh, Gissler and Laursen2013) and, in meta-analyses, the pooled risk of all-cause mortality is over twice as high than in comparison populations regardless of the time span assessed (Correll et al., Reference Correll, Solmi, Croatto, Schneider, Rohani-Montez, Fairley, Smith, Bitter, Gorwood, Taipale and Tiihonen2022; Walker et al., Reference Walker, McGee and Druss2015), putting health equity into question (Thornicroft, Reference Thornicroft2011).

One of the main causes of death for persons with SMI is cancer (Coldefy and Gandré, Reference Coldefy and Gandré2018; Lawrence et al., Reference Lawrence, Kisely and Pais2010), just like in the general population. The risk of cancer mortality is, however, higher in persons with SMI, regardless of a similar or possibly lower cancer incidence (Charlesworth et al., Reference Charlesworth, Fegan and Ashmore2023; Grassi et al., Reference Grassi, Stivanello, Belvederi Murri, Perlangeli, Pandolfi, Carnevali, Caruso, Saponaro, Ferri, Sanza, Fioritti, Meggiolaro, Ruffilli, Nanni, Ferrara, Carozza, Zerbinati, Toffanin, Menchetti and Berardi2021; Kisely et al., Reference Kisely, Crowe and Lawrence2013; Li et al., Reference Li, Li, Yu, Zheng, Sun, Lu, Zhang, Li and Bi2018; Mahar et al., Reference Mahar, Kurdyak, Hanna, Coburn and Groome2020; Pettersson et al., Reference Pettersson, Gissler, Hällgren, Ösby, Westman and Bobo2020). This suggests that factors beyond health behaviours, intervening after the onset of cancer, may play a significant role in this excess mortality. Studies have also shown that patients with SMI are more likely to have metastases (Charlesworth et al., Reference Charlesworth, Fegan and Ashmore2023; Kisely et al., Reference Kisely, Crowe and Lawrence2013) and more advanced stages of cancer at presentation compared to the general population (Ishikawa et al., Reference Ishikawa, Yasunaga, Matsui, Fushimi and Kawakami2016), which could be partly explained by lower cancer screening rates (Gandré and Coldefy, Reference Gandré and Coldefy2020; Howard et al., Reference Howard, Barley, Davies, Rigg, Lempp, Rose, Taylor and Thornicroft2010; Solmi et al., Reference Solmi, Firth, Miola, Fornaro, Frison, Fusar-Poli, Dragioti, Shin, Carvalho, Stubbs, Koyanagi, Kisely and Correll2020; Thomsen et al., Reference Thomsen, Jørgensen, Pedersen, Erichsen, Sørensen and Mikkelsen2023) and longer delays for primary care consultations (Howard et al., Reference Howard, Barley, Davies, Rigg, Lempp, Rose, Taylor and Thornicroft2010). Currently, the available literature on the role of healthcare-related factors in cancer survival also points towards less appropriate and well-organized care provision to persons with SMI at different points along the care continuum (Mahar et al., Reference Mahar, Kurdyak, Hanna, Coburn and Groome2020; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Aggarwal, Stewart and Davies2023). However, the evidence on care timeliness and adequacy remains scarce and inconclusive, and few studies have used comprehensive population-based data covering both community and hospital care to assess access to guideline-appropriate cancer care, beyond isolated aspects of care pathways. In the case of some common cancers, such as colorectal cancer (CRC), existing research is often restricted to limited populations (e.g., the elderly, or individuals with schizophrenia only) and rarely addresses care after diagnosis (Protani et al., Reference Protani, Alotiby, Seth, Lawrence, Jordan, Logan, Kendall, Siskind, Sara and Kisely2022), or solely for a few health services (e.g., emergency surgery or palliative care).

In this context, the aim of our research was to compare the quality of cancer care pathways from screening to end-of-life care in patients with and without SMI in France, using national, population-based health claims data covering community and hospital care, and a matched cohort study design. We focused on CRC, which is among the most common types of cancer and leading causes of cancer-related deaths in France (OECD, 2023), with 47,582 new cases in 2023 (Lapôtre-Ledoux et al., Reference Lapôtre-Ledoux, Remontet, Uhry, Dantony, Grosclaude, Molinié, Woronoff, Lecoffre-Bernard, Lafay, Defossez and D’Almeida2023), and which has been associated with increased mortality in persons with SMI worldwide (Charlesworth et al., Reference Charlesworth, Fegan and Ashmore2023; Correll et al., Reference Correll, Solmi, Croatto, Schneider, Rohani-Montez, Fairley, Smith, Bitter, Gorwood, Taipale and Tiihonen2022; Cunningham et al., Reference Cunningham, Sarfati, Stanley, Peterson and Collings2015; Ishikawa et al., Reference Ishikawa, Yasunaga, Matsui, Fushimi and Kawakami2016).

Methods

Data source

We used real-world data from the French national health claims database (Système National des Données de Santé, SNDS), which contains data on all care-related reimbursements made by the statutory health insurance (SHI). As France has universal healthcare coverage through the SHI, the SNDS covers the entire French population. A pseudonymized patient identifier enables linking all reimbursed outpatient care acts (consultations, medical procedures and drugs dispensed to patients), hospital stays in public and private hospitals, and information on patients’ inclusion in several state-subsidised health insurance schemes (for instance, for persons with low income or long-term illness [LTI]). The SNDS also contains basic demographic data on patients, as well as a unique identifier for each care provider. Persons with long-term conditions, such as SMI and cancer, are identified via the standardized Healthcare Expenditures and Conditions Mapping (HECM) (Cartographie des Pathologies et des Dépenses) tool, which combines causes for hospitalizations, reasons for entering the LTI scheme, dispensed drugs and medical procedures to identify these conditions (Rachas et al., Reference Rachas, Gastaldi-Ménager, Denis, Barthélémy, Constantinou, Drouin, Lastier, Lesuffleur, Mette, Nicolas, Pestel, Rivière, Tajahmady, Gissot and Fagot-Campagna2022).

Study population

Our study population included all men and women, 18 years of age or older; treated for incident colon, rectal or both cancers (double location) (International Classification of Diseases [ICD-10] codes C18 [except C181], C19, C20); without or with lymph-node involvement (C775); and without or with synchronous metastases (C77 [except C775], C78, C79). To obtain a sufficient sample size for analysing the impact of SMI in different subgroups of CRC patients, we included SHI beneficiaries with incident CRC over a period of 4 years (2015–2018). We did not include incident cases from 2019 onwards, as cancer screening and care were strongly affected by the COVID-19 pandemic (CNAM, 2022a). Having CRC a given year was defined through the HECM tool as being hospitalized or included in the LTI scheme for CRC, or having CRC-specific drugs or medical procedures. Incidence was defined by an absence of hospitalizations and LTI inclusions for CRC in the 5 preceding years, and an absence of CRC-specific drugs and medical procedures in the preceding 365 days. To avoid heterogeneity in care pathways, we excluded patients treated for other cancers concomitantly or in the year before CRC incidence, as well as patients with in situ CRC (ICD-10 codes D01.0, D01.1 and D01.2) for the analysis of cancer care pathways.

We then identified CRC patients with pre-existing SMI, i.e., having SMI in the year preceding cancer incidence. Included conditions were, in accordance with international literature (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Choi, Lizano, Yuan, Yu, Smoller and Kohane2022), schizophrenia, schizotypal and delusional disorders (ICD-10 codes F20-F29) as well as manic episodes and bipolar affective disorders (ICD-10 codes F30 and F31). Having SMI a given year was defined through the HECM tool as being included in the LTI scheme for SMI that year, or hospitalized for SMI in the past 2 years, or hospitalized for SMI in the past 5 years while still receiving recurrent antipsychotic drug treatment, i.e., at least three deliveries of such treatments over the year – including most drugs with Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical codes starting by N05 and lithium (CNAM, 2022b). To take into account the cyclic nature of SMI, patients not identified with an SMI but with a recurrent antipsychotic drug treatment in the year prior to cancer incidence, were considered to have pre-existing SMI if they had SMI in the year of cancer incidence.

Study design

To obtain comparable groups of CRC patients with and without SMI in terms of demographics and cancer characteristics, we adopted a matched cohort study design using exact matching with replacement. We matched each patient with SMI to three patients without SMI based on age (±5 years), sex, region of residence, year of cancer incidence, cancer location (colon, rectum or both) and cancer type at presentation (invasive non-metastatic without lymph-node involvement, invasive non-metastatic with lymph-node involvement and synchronous metastatic). Patients with onset of SMI after CRC diagnosis were excluded from the pool of potential matches.

Cancer care pathways and quality indicators

Data on care pathways included, depending on the cancer type and location, participation in the national CRC screening programme (faecal immunochemical test) within 12 months before cancer incidence, main diagnostic examinations received and their total number, treatments and treatment combinations received, as well as post-treatment follow-up.

To assess the quality of CRC care pathways, we used nationally established quality of care (QOC) indicators developed by the French National Cancer Institute (Institut National du Cancer, INCa), under the umbrella of the French national health authority (Haute autorité de santé, HAS). The indicators cover diagnosis and cancer staging, timeliness of treatments, 90-day postoperative mortality, post-treatment follow-up and end-of-life care, and assess the proportion of patients having received care according to established recommendations for their specific type of cancer. Two thresholds define the level of QOC for each indicator: a target threshold, such as the ideal proportion of patients that should be receiving a colonoscopy before their first treatment (≥90%), and an alert threshold raising concern for care quality, for instance if less than 80% of patients receive a colonoscopy before their first treatment (INCa, 2022). The original thresholds for postoperative mortality and post-treatment follow-up were not applicable to our study, as they were initially constructed for comparing mortality and follow-up between hospitals and not populations. The 90-day postoperative mortality indicator, originally reflecting hospital mortality, was adapted to reflect mortality in our study population.

Covariates

We included one comprehensive clinical covariate: the mortality-related morbidity index (MRMI), which is a quantified measure of overall morbidity, specifically developed for the SNDS data, and based on the presence of the most common chronic diseases. These include cardiovascular and respiratory disorders, diabetes, chronic renal failure, multiple sclerosis, paraplegia, epilepsy, dementia, Parkinson’s disease, liver and pancreatic disorders, inflammatory bowel diseases and substance use disorders (Constantinou et al., Reference Constantinou, Tuppin, Fagot-Campagna, Gastaldi-Ménager, Schellevis and Pelletier-Fleury2018). This index was adapted to our study by excluding SMI and cancers from the potential comorbidities (modified MRMI). While the use of this index is optimal within a population that has not been selected on a given condition, it still demonstrates a higher performance than other widely used indexes (Elixhauser and Charlson) for individuals with specific disorders in the SNDS data (CNAM, 2021).

Socio-economic covariates included patients’ inclusion in the publicly subsidised complementary health insurance (Couverture Maladie Universelle Complémentaire, CMU-C), or in the voucher plan for the purchase of a complementary health insurance (Aide à l’acquisition d’une Complémentaire Santé, ACS), which were combined into a single variable used as a proxy for low income, as they are only available for persons with limited earnings.

Care provider-related covariates included the type of the main hospital providing CRC care (public general hospital, public teaching hospital, non-profit comprehensive cancer centre – Centre de Lutte Contre le Cancer, CLCC –, private non-profit hospital or private-for-profit hospital). To take into account geographical differences in care provision, we used a measure of local potential accessibility to general practitioners (GPs) calculated at the patient’s residential zip code (Barlet et al., Reference Barlet, Coldefy, Collin and Lucas-Gabrielli2012) as well as the density of gastroenterologists and hepatologists in the county (département) of residence at the year of cancer incidence (DREES, 2021), which were both used as continuous variables to avoid information loss. At an individual level, we also assessed whether each patient had a referring physician (médecin traitant) reported in the year of cancer incidence.

Statistical analyses

First, we compared the sociodemographic and clinical characteristics of all CRC patients with and without SMI prior to matching, using Chi2 and Wilcoxon tests. After matching, we assessed differences between patients with and without SMI in participation in the national CRC screening programme (among eligible patients; aged 50–74 years) and receipt of main diagnostic examinations, treatments and post-treatment follow-up, for colon and rectal cancer and invasive non-metastatic and metastatic cancer separately where relevant. We then assessed whether QOC thresholds were attained and estimated differences in QOC indicators between the two groups. For this, we used simple and multivariable conditional logistic regression models for binary variables or conditional Poisson regressions for count variables, taking into account correlation between matched patients, and adjusting for relevant socio-economic, clinical and care provider-related covariates: low income and MRMI (all models), having a referring physician (for screening), local potential accessibility to GPs (for screening and diagnosis), density of gastroenterologists and hepatologists in the county of residence (for diagnostic and follow-up colonoscopy) and type of hospital providing CRC care (for treatment and follow-up).

Results

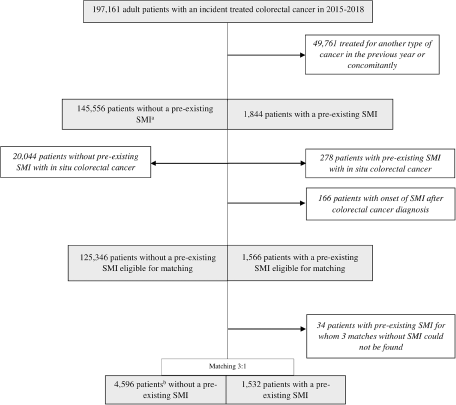

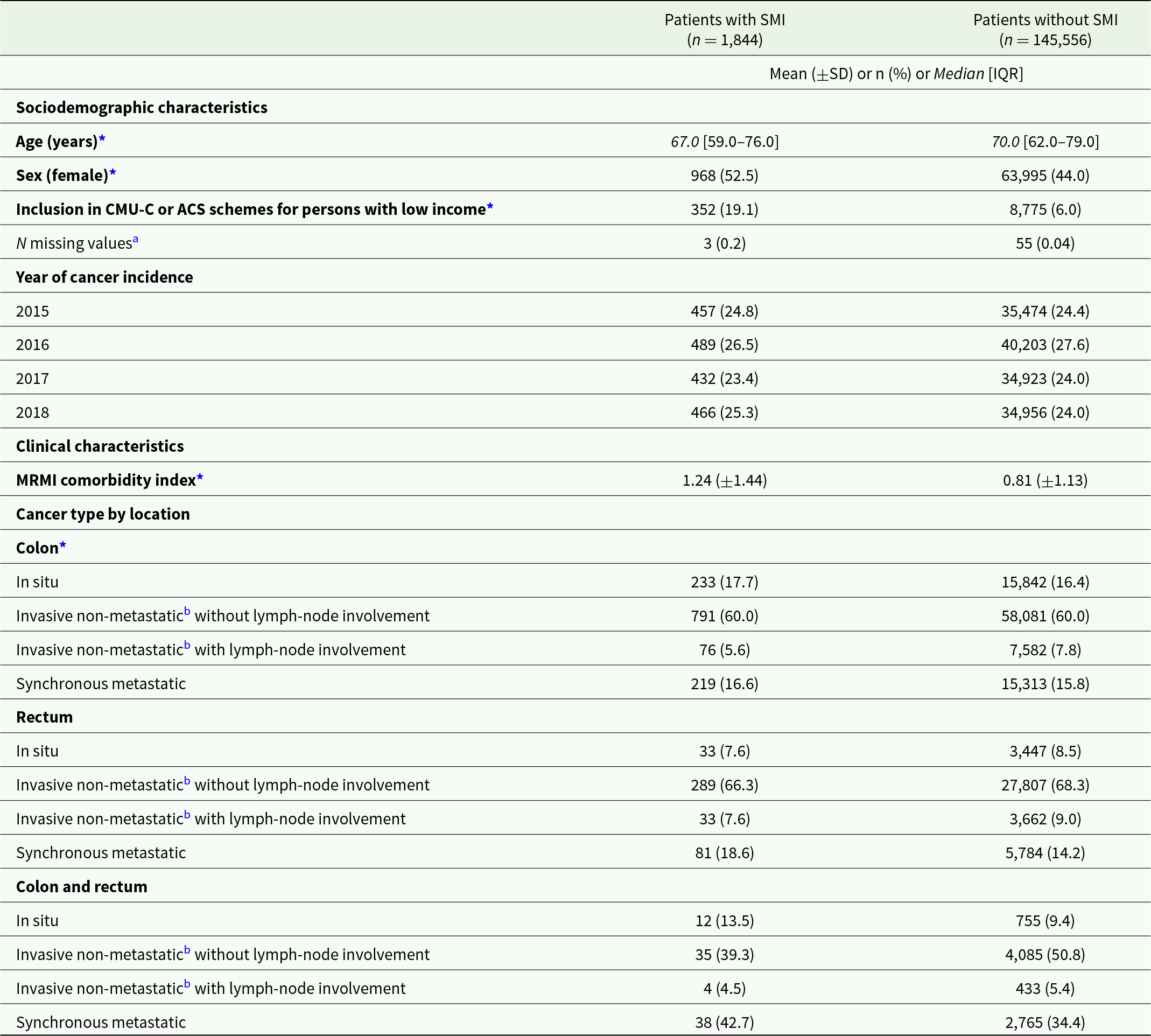

A total of 147,400 patients had incident CRC without other concomitant cancers in 2015–2018 (Fig. 1). Among these patients, 1,844 (1.3%) had pre-existing SMI. Patients with SMI were more likely to be younger, female and to have low income, a higher number of comorbidities and colon cancer compared to patients without SMI (Table 1). For each type of cancer, patients with SMI had higher rates of metastatic cancer at presentation. After excluding patients with in situ CRC, 1,532 patients with pre-existing SMI were matched with 3 patients without SMI (Fig. 1). Matches could not be found for 34 (2.2%) patients with SMI (Fig. 1 and Supplementary Table S1).

Figure 1. Study flow chart.

Table 1. Characteristics of colorectal cancer patients with and without pre-existing SMI (before matching)

Abbreviations: SD: standard deviation; IQR: interquartile range; CMU-C: couverture maladie universelle complémentaire (publicly subsidised complementary health insurance); ACS: Aide à l’acquisition d’une Complémentaire Santé (voucher plan for the purchase of a complementary health insurance); MRMI: mortality-related morbidity index.

a Values missing at the year of cancer incidence were completed with data retrieved from the preceding year, when available.

b Or metachronous metastatic.

* p < 0.05 for the difference between the two groups with and without SMI.

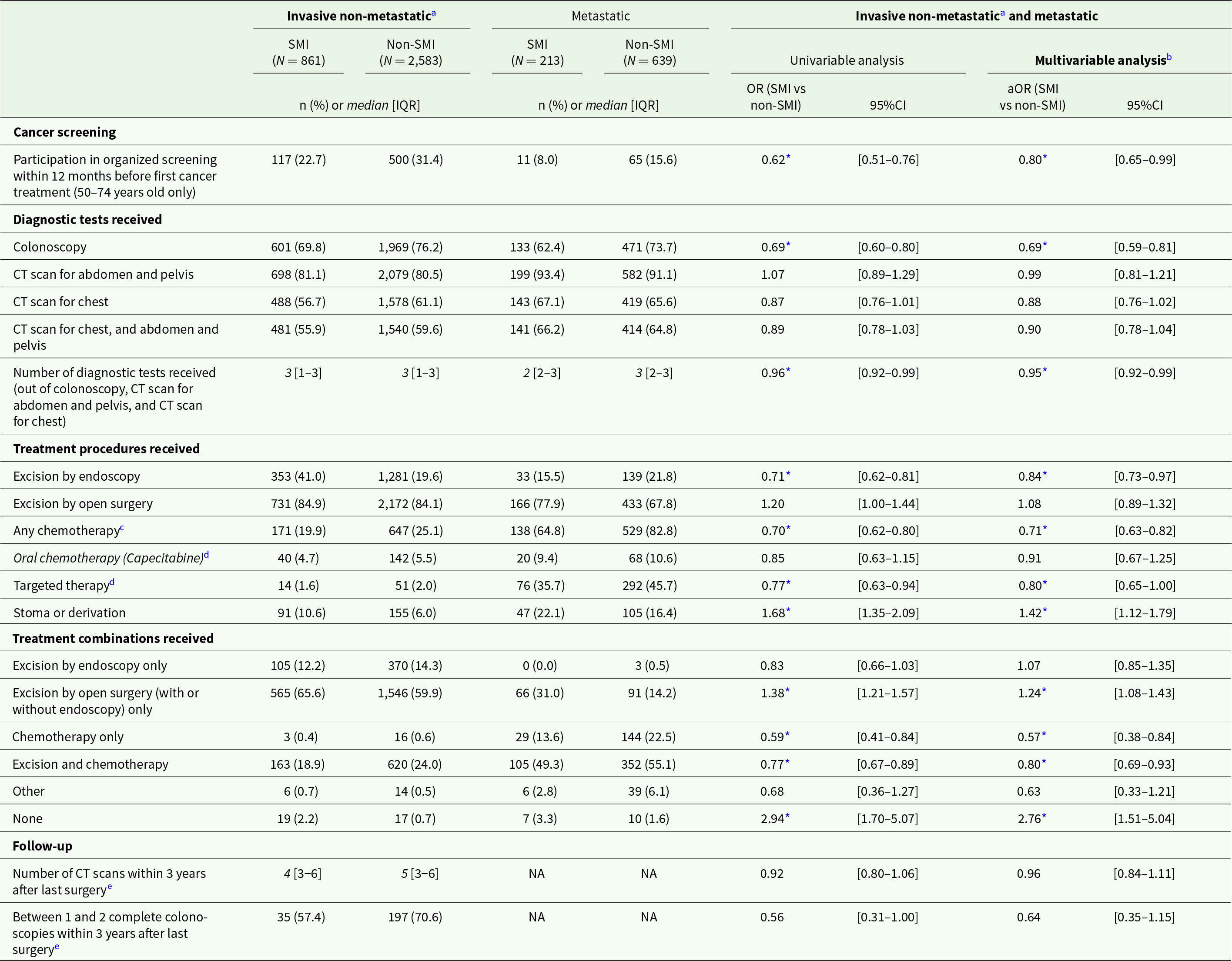

Differences in cancer care between matched patients with and without SMI were observed for patients with both non-metastatic and metastatic CRC. After matching and adjusting for clinical, socio-economic and care provider-related covariates, colon cancer patients with SMI were less likely to participate in the national CRC screening programme (adjusted odds ratio [aOR] = 0.80; 95% confidence interval [95%CI]: 0.65–0.99) and to receive colonoscopy (aOR = 0.69; 95%CI: 0.59–0.81), and had a lower average number of recommended diagnostic examinations (aOR = 0.95; 95%CI: 0.92–0.99) compared to patients without SMI (Table 2). Regarding treatment, they were less likely to receive excision by endoscopy (aOR = 0.84; 95%CI: 0.73–0.97) as well as any chemotherapy (aOR = 0.71; 95%CI: 0.63–0.82) and targeted therapy (aOR = 0.80; 95%CI: 0.65–1.00), but more likely to have stoma (aOR = 1.42; 95%CI: 1.12–1.79). Regarding treatment combinations, they were less likely to receive both excision and chemotherapy (aOR = 0.80; 95%CI: 0.69–0.93) and more likely to receive open surgery only (aOR = 1.24; 95%CI: 1.08–1.43) or no treatment at all (aOR = 2.76; 95%CI: 1.51–5.04).

Table 2. Cancer care received by matched colon cancer patients with and without SMI, and odds for patients with SMI to receive each care item compared to patients without SMI

Abbreviations: IQR: interquartile range; (a)OR: (adjusted) odds ratio; 95%CI: 95% confidence interval; CT: computed tomography; NA: not applicable.

Note: all analyses exclude patients with colon and rectal cancer (double location).

a Or metachronous metastatic.

b Adjusting for clinical, socio-economic and care provider-related covariates

c Intravenous or oral (capecitabine).

d Adjuvant or neoadjuvant.

e Among patients with invasive non-metastatic colon cancer who had cancer surgery in combination with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy, and with data available at least 39 months after last surgery (maximum until 2021). Excluding patients with Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, Lynch’s syndrome or familial adenomatous polyposis, or who developed metastatic cancer, had recurrence of cancer, moved abroad or deceased during the follow-up period. Sample size: N = 61 and N = 279 for patients with and without SMI, respectively).

* p < 0.05

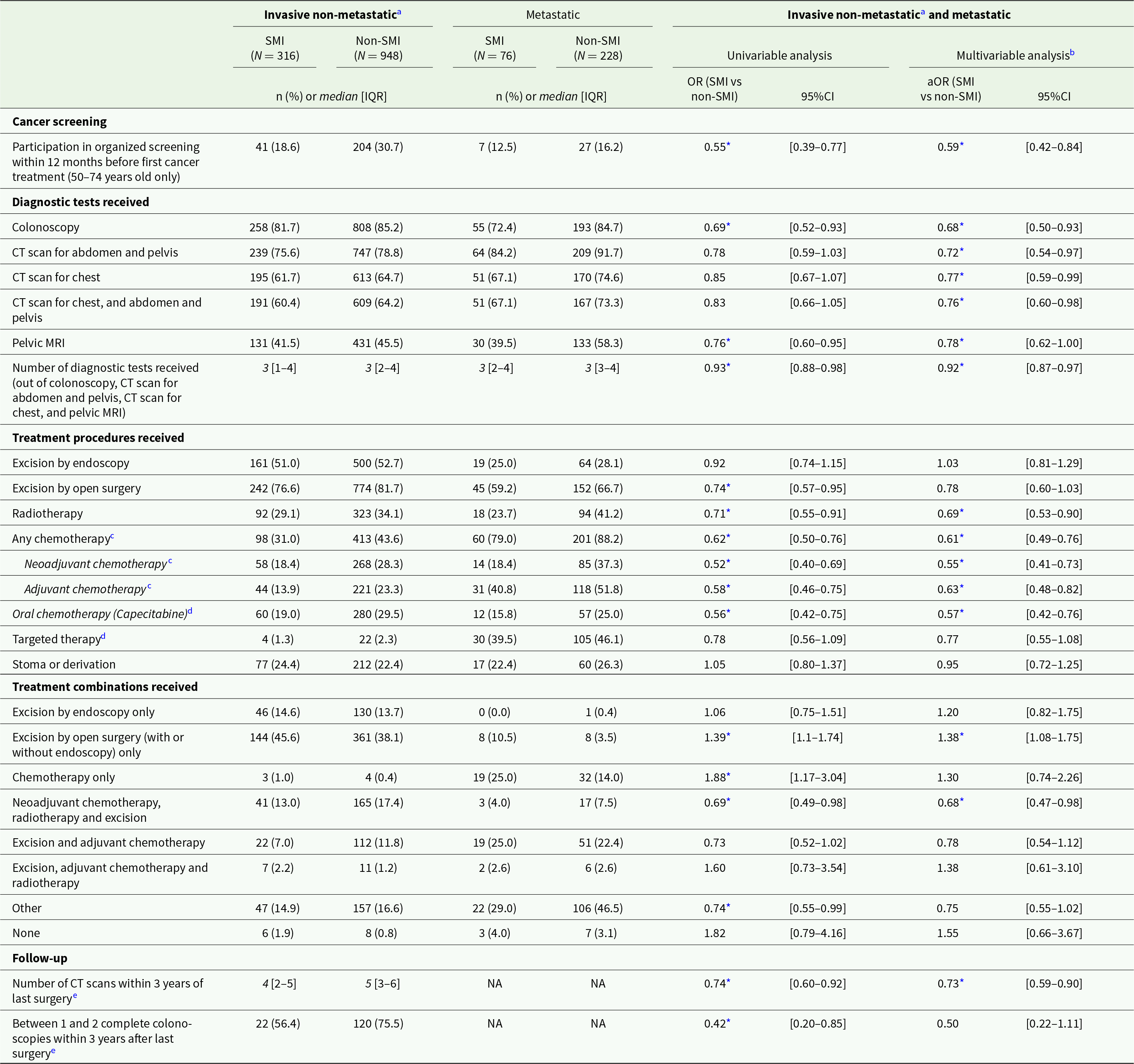

Findings were similar for patients with SMI and rectal cancer (Table 3). They were less likely to participate in the national CRC screening programme (aOR = 0.59; 95%CI: 0.42–0.84) and to receive colonoscopy (aOR = 0.68; 95%CI: 0.50–0.93). Patients with SMI also had a lower average number of diagnostic examinations (aOR = 0.92; 95%CI: 0.87–0.97) and were less likely to receive CT scans (aORs between 0.72 and 0.77) and pelvic MRI (aOR = 0.78; 95%CI: 0.62–1.00). Regarding treatment, they had lower odds of receiving radiotherapy (aOR = 0.69; 95%CI: 0.53–0.90) as well as chemotherapy (e.g., any chemotherapy: aOR = 0.61; 95%CI: 0.49–0.76, and capecitabine: aOR = 0.57; 95%CI: 0.42–0.76). Regarding treatment combinations, patients with SMI were less likely to receive a combination of neoadjuvant chemotherapy, radiotherapy and excision (aOR = 0.68; 95%CI: 0.47–0.98), and more likely to receive open surgery only (aOR = 1.38; 95%CI: 1.08–1.75). Regarding post-treatment care, they were less likely to receive follow-up CT scans (aOR = 0.73, 95%CI: 0.59–0.90).

Table 3. Cancer care received by matched rectal cancer patients with and without SMI, and odds for patients with SMI to receive each care item compared to patients without SMI

Abbreviations: IQR: interquartile range; SD: standard deviation; (a)OR: (adjusted) odds ratio; 95%CI: 95% confidence interval; CT: computed tomography; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging; NA: not applicable.

Note: all analyses exclude patients with colon and rectal cancer (double location).

a Or metachronous metastatic.

b Adjusting for clinical, socio-economic and care provider-related covariates.

c Intravenous or oral (capecitabine).

d Adjuvant or neoadjuvant.

e Among patients with invasive non-metastatic colon cancer who had cancer surgery in combination with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy, and with data available at least 39 months after last surgery (maximum until 2021). Excluding patients with Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, Lynch’s syndrome or familial adenomatous polyposis, or who developed metastatic cancer, had recurrence of cancer, moved abroad or deceased during the follow-up period. Sample size: N = 39 and N = 159 patients with and without SMI, respectively).

* p < 0.05.

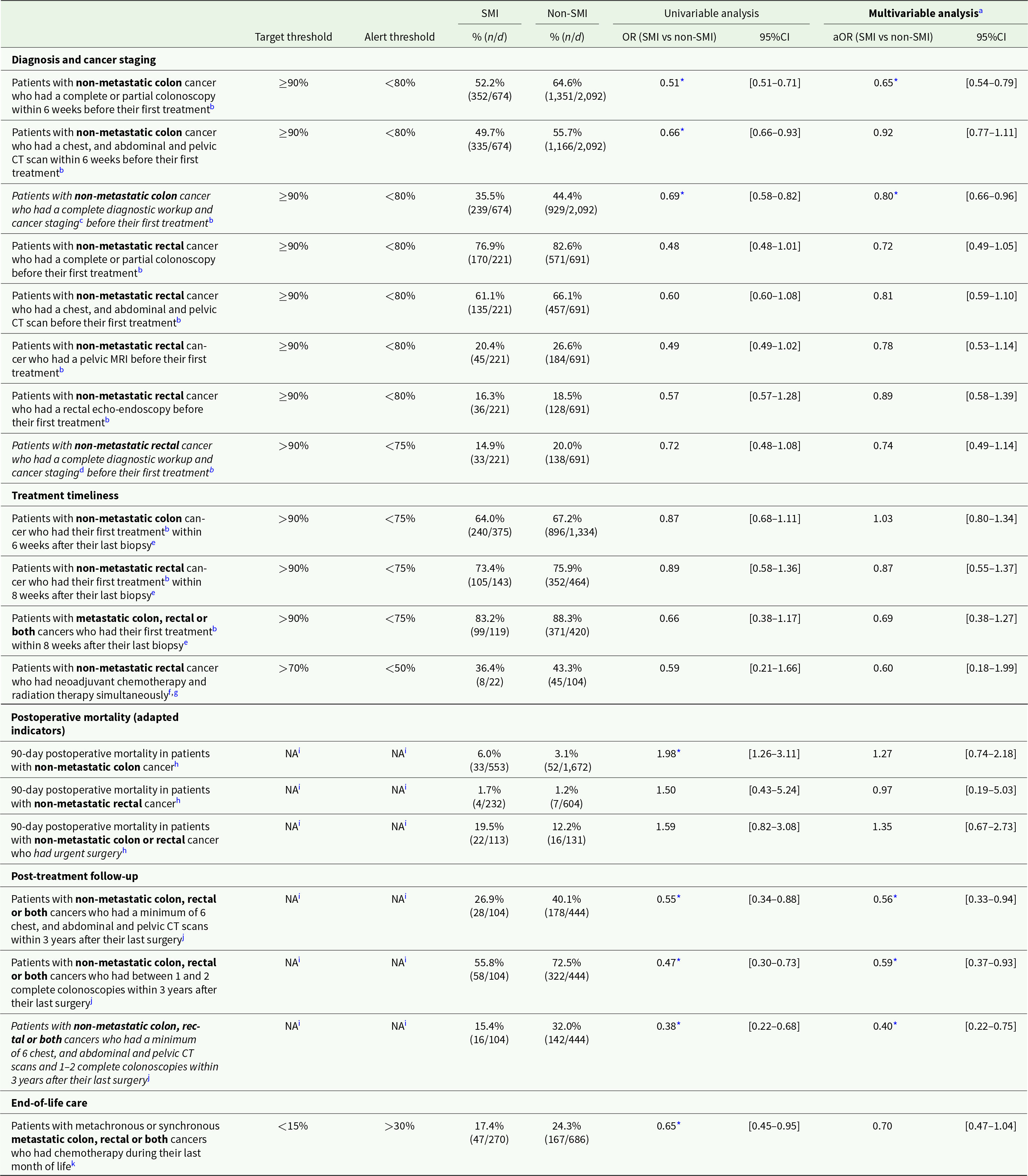

Regarding the QOC indicators, none of the target thresholds were attained regardless of SMI status, but patients with SMI were systematically farther from attaining them (Table 4). For patients with SMI, all but two indicators on timeliness between diagnosis and treatment and end-of-life-care (Table 4), were within the alert range, raising concern for the quality of their care pathways. For patients without SMI, all but three indicators – also on care timeliness and end-of-life care (Table 4) – were within the alert range. After adjusting for covariates, statistically significant differences between patients with and without SMI were found for indicators focusing on diagnosis and cancer staging as well as post-treatment follow-up. Patients with SMI and non-metastatic colon cancer were significantly less likely to have a complete diagnostic workup and cancer staging before their first treatment (aOR = 0.80; 95%CI: 0.66–0.96) and patients with SMI and non-metastatic colon, rectal or both cancers were less likely to have postoperative CT scans and colonoscopies within 3 years after their last surgery (aOR = 0.40; 95%CI: 0.22–0.75) compared to patients without SMI (Table 4).

Table 4. Indicators of the quality of cancer care pathways in patients with and without pre-existing SMI

Abbreviations: n: numerator; d: denominator; (a)OR: (adjusted) odds ratio; 95%CI: 95% confidence interval; CT: computed tomography; MRI: magnetic resonance imaging.

Note: Metachronous metastatic cancers were considered non-metastatic unless otherwise stated.

a Adjusting for clinical, socio-economic and care provider-related covariates.

b Calculated among patients who had chemotherapy, radiotherapy or open surgery. Excluding patients who had their first radiotherapy in the private sector, whose first treatment was urgent surgery, and patients for whom a first treatment was not identified. or oral chemotherapy. For indicators “Patients with non-metastatic colon cancer who had a complete diagnostic workup and cancer staging before their first treatment” and “Patients with non-metastatic rectal cancer who had a complete diagnostic workup and cancer staging before their first treatment”: patients whose first treatment was oral chemotherapy were also excluded.

c Complete or partial colonoscopy, biopsy, and chest, and abdominal and pelvic CT scan within 6 weeks before first treatment.

d Complete or partial colonoscopy, biopsy, and chest, abdominal and pelvic CT scan within 8 weeks before first treatment, and pelvic MRI within 4 weeks before first treatment.

e Calculated among patients who had a biopsy.

f Intravenous chemotherapy within ±5 days or oral chemotherapy (capecitabine) within ±7 days of neoadjuvant radiation therapy.

g Calculated among patients who had cancer surgery and radiotherapy, excluding patients who had radiotherapy in the private sector.

h Mortality regardless of cause. Calculated among patients who had cancer surgery and included in the General Health Insurance scheme (regime general) only. Excluding patients with Crohn’s disease or ulcerative colitis.

i As the indicators were originally developed to assess QOC at the hospital level, the thresholds for postoperative mortality and follow-up were not applicable to our study.

j Among patients with invasive non-metastatic colon cancer who had cancer surgery in combination with chemotherapy and/or radiotherapy, and with data available at least 39 months after last surgery (maximum until 2021). Excluding patients with Crohn’s disease, ulcerative colitis, Lynch’s syndrome or familial adenomatous polyposis, or who developed metastatic cancer, had recurrence of cancer, moved abroad or deceased during the follow-up period.

k Calculated among deceased patients with metachronous or synchronous metastatic colon, rectal or both cancers.

* p < 0.05

Discussion

Based on exhaustive population-based data and a matched cohort study design, our findings reveal discrepancies in CRC care pathways from screening to post-treatment follow-up between patients with and without SMI. We consistently found less participation in the national CRC screening programme, less advanced diagnostic examinations as well as a lower likelihood of receiving certain treatment combinations and capecitabine or targeted therapy in patients with SMI, for both colon and rectal cancer. Differences were also found in post-treatment follow-up, but only for patients with rectal cancer. None of the QOC target thresholds were attained, with patients with SMI being farther from attaining them, and most indicators were within the alert range for both patients with and without SMI. This raises questions about care organization, quality and practices, even though underreporting of certain procedures may occur, requiring caution when interpreting the results. All in all, significant differences were found for QOC indicators focusing on diagnosis and post-treatment follow-up, but not for other indicators.

Our findings underscore that discrepancies in CRC care for patients with SMI already start at the entry stage of care pathways and in particular screening, while it is free of charge in France. Previous research suggests that many of the reasons for non-uptake of cancer screening are similar in persons with SMI and the general population, although reported more frequently in persons with SMI, such as practical barriers (e.g., no transport, lack of formal reminders) or embarrassment (Howard et al., Reference Howard, Barley, Davies, Rigg, Lempp, Rose, Taylor and Thornicroft2010). In addition, concerns directly related to SMI may be competing with preventive care (including screening) and less acute physical health concerns, especially if the SMI is exacerbated, or coexisting with other chronic conditions (Bhatia et al., Reference Bhatia, Sutradhar, Tinmouth, Singh, Lau and Lipscombe2021; Jensen et al., Reference Jensen, Pedersen, Andersen, Vestergaard and Vedsted2015).

Discrepancies were further observed in diagnostic examinations received: patients with SMI were less likely to have colonoscopy, several other recommended diagnostic examinations, and a complete diagnostic workup and cancer staging before their first treatment. This is consistent with research on other types of cancer, such as breast cancer, where women with SMI were found to have a lower likelihood of receiving the recommended diagnostic examinations compared to women without SMI (Seppänen et al., Reference Seppänen, Daniel, Houzard, Le Bihan, Coldefy and Gandré2023). Diagnostic overshadowing by healthcare providers, i.e., attributing somatic complaints to SMI, is hypothesized to contribute to disparities in diagnosis (Howard et al., Reference Howard, Barley, Davies, Rigg, Lempp, Rose, Taylor and Thornicroft2010; Thornicroft, Reference Thornicroft2011). This could lead to diagnostic examinations being delayed until the situation becomes more acute or to cancer only being discovered during examinations for other conditions. It is thus possible that some of the colon cancer cases were discovered during emergency surgery, for instance for occlusion, which is why colonoscopies where not performed. Yet, colonoscopy rates remain the lowest in the patients with SMI even after positive faecal occult blood tests (Bhatia et al., Reference Bhatia, Sutradhar, Paszat, Rabeneck, Singh, Tinmouth and Lipscombe2022). Qualitative research and other reports from care providers point out difficulties to perform invasive procedures on patients with SMI, including greater challenges in preparing them for colonoscopy (Thomsen et al., Reference Thomsen, Jørgensen, Pedersen, Erichsen, Sørensen and Mikkelsen2023), and stigmatizing perceptions related to their mental disorder, such as undesired behaviour at the hospital, or tendencies to miss medical appointments, which can influence care-related decisions (Gandré et al., Reference Gandré, Moreau, Ben Dridi and Seppänen2023; Grassi and Riba, Reference Grassi and Riba2021; Howard et al., Reference Howard, Barley, Davies, Rigg, Lempp, Rose, Taylor and Thornicroft2010; Thornicroft, Reference Thornicroft2011; Tuesley et al., Reference Tuesley, Jordan, Siskind, Kendall and Kisely2019).

Along the cancer care continuum, our results also demonstrate disparities in CRC treatment for patients with SMI. They were less likely to receive certain care combinations (excision and chemotherapy for colon cancer, and neoadjuvant chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and excision for rectal cancer), and to have access to targeted therapy or capecitabine compared to patients without SMI, but more likely to receive invasive forms of treatment such as stoma. Our results are congruent with international research on colorectal and other cancers (Ishikawa et al., Reference Ishikawa, Yasunaga, Matsui, Fushimi and Kawakami2016; Kisely et al., Reference Kisely, Crowe and Lawrence2013; Protani et al., Reference Protani, Alotiby, Seth, Lawrence, Jordan, Logan, Kendall, Siskind, Sara and Kisely2022) and complement our previous findings on breast cancer (Seppänen et al., Reference Seppänen, Daniel, Houzard, Le Bihan, Coldefy and Gandré2023), reproducing results on a large sample of both men and women. The observed differences in treatments may stem from a range of factors. More invasive treatments may result from more advanced cancer at presentation, which we were only able to assess using the subtype of cancer at diagnosis. However, other studies have shown that even when taking cancer stage into account, differences in care approaches remain (Ishikawa et al., Reference Ishikawa, Yasunaga, Matsui, Fushimi and Kawakami2016; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Aggarwal, Stewart and Davies2023). An increased risk of complications related to cancer treatments, for instance due to drug interactions with antipsychotic medications, could also conduct care providers to avoid some treatment options, such as chemotherapy, for patients with SMI (Glasdam et al., Reference Glasdam, Hybholt and Stjernswärd2023; Howard et al., Reference Howard, Barley, Davies, Rigg, Lempp, Rose, Taylor and Thornicroft2010). Furthermore, certain cancer treatments, such as radiotherapy, may cause distress in patients with paranoia, hallucinations or severe anxiety, due to the clinical set-up (restrained movement and being unaccompanied during the treatment), in which case surgical excision might be preferable (Howard et al., Reference Howard, Barley, Davies, Rigg, Lempp, Rose, Taylor and Thornicroft2010). Adverse effects from certain treatments can also be considered too severe for a person with SMI to manage alone, especially in the case of social isolation (Gandré et al., Reference Gandré, Moreau, Ben Dridi and Seppänen2023).

Moreover, significant discrepancies between patients with and without SMI were found for some of the post-treatment follow-up variables, consistent with our previous findings on breast cancer (Seppänen et al., Reference Seppänen, Daniel, Houzard, Le Bihan, Coldefy and Gandré2023). These findings could reflect the siloed nature of physical and mental healthcare, that has been highlighted in a number of national contexts (Gandré et al., Reference Gandré, Moreau, Ben Dridi and Seppänen2023; Irwin et al., Reference Irwin, Park, Shin, Fields, Jacobs, Greer, Taylor, Taghian, Freudenreich, Ryan and Pirl2017), and which could be an important limiting factor for effective transitional and follow-up care. However, statistically significant differences between patients with and without SMI regarding post-treatment follow-up were not found for all variables and population subgroups included in our analyses.

Finally, our results underscore the need to improve the overall quality of cancer care pathways for both patients with and without SMI. None of the QOC target thresholds were attained, and most indicators were within the alert range, indicating that the provision of recommended CRC diagnosis, treatment and post-treatment procedures may be suboptimal. Although patients with SMI were systematically farther from attaining the thresholds, we only found statistically significant differences between the two groups for QOC indicators focusing on the entry (diagnosis) and exit (post-treatment follow-up) stages of care pathways. Regardless of resorting to data on the whole French population, our analyses may be underpowered to detect differences in the smaller subpopulations included in the calculation of some of the QOC indicators and should be interpreted with caution. Thus, similar disparities may exist along the rest of the care pathways, but that our study was underpowered to detect. In addition, differences compared to the general population should not be the only indicator to consider; in their absence, major systemic QOC improvements may still be necessary (McGinty et al., Reference McGinty, Zhang, Guallar, Ford, Steinwachs, Dixon, Keating and Daumit2012), requiring particular efforts to avoid exacerbating inequities, as health- and care-related improvements in vulnerable populations often lag behind those in the general population (Solmi et al., Reference Solmi, Firth, Miola, Fornaro, Frison, Fusar-Poli, Dragioti, Shin, Carvalho, Stubbs, Koyanagi, Kisely and Correll2020).

Our findings should be interpreted in light of several limitations. The SNDS is based on health claims data and therefore only allows identifying persons with SMI that resort to the healthcare system. Furthermore, persons that do not seek care may also have undiagnosed or late diagnosis of cancer. Our findings therefore provide a conservative estimate of differences in cancer care between persons with and without SMI. The SNDS data also contain limited individual clinical and sociodemographic data. Thus, we did not have access to cancer stage at presentation, health-related behaviours (smoking, body mass index, etc.) and detailed socio-economic factors (such as profession, country of origin and family situation) that may impact access, timeliness and use of healthcare services and health outcomes (Cabassa, Reference Cabassa2023; Gandré et al., Reference Gandré, Moreau, Ben Dridi and Seppänen2023; Loretti, Reference Loretti2021; OECD, 2023). It is additionally possible that some healthcare procedures, such as CT scans, are underreported, leading to an underestimation of their use. However, our aim was to compare care between patients with and without SMI, for whom potential underreporting is unlikely to be different. The SNDS also does not contain data on participation in therapeutic patient education programmes nor in supportive cancer care, not always covered by the SHI but increasingly part of care recommendations (NHS England, 2016). Moreover, although matching is a robust technique for group comparisons, some patients with SMI could not be matched to three patients without SMI, and were consequently excluded from our analyses. However, these patients only represented 2% of individuals with SMI and incident cancer, which is likely to have limited impact on our results. Finally, we were not able to assess the reasons for non-receipt of some health services along the CRC care pathways. Therefore, we cannot conclude directly on whether discrepancies in care between patients with and without SMI stem from supply-side (provider-related) or demand-side (patient-related) factors. Nevertheless, a complementary qualitative approach to this research points to a role of both (Gandré et al., Reference Gandré, Moreau, Ben Dridi and Seppänen2023), while we were able to identify where inequities emerge along the cancer care pathways, which can inform interventions designed to reduce inequities in healthcare that should notably target the entry and exit stages of care pathways where most disparities were found. Our analyses may have been underpowered to detect all potential discrepancies in care pathways, and we were unable to perform adjusted analyses in subpopulations, such as by type of cancer and sex. Further research using larger sample sizes is needed for assessing potential discrepancies these subpopulations, notably in countries with more inhabitants, since we already used exhaustive data for France.

All in all, despite limitations, our study was based on comprehensive population-based health claims data covering the whole French population and allowing for the identification of an appropriate control group, as well as on nationally established QOC indicators covering all phases of CRC care pathways. This allows providing novel knowledge on discrepancies in guideline-concordant care in patients with SMI in real-world practice while yielding good external validity. Our findings can therefore be used to inform clinical practice, policy-making and further research.

Conclusions

Our findings reveal discrepancies across the CRC care continuum in France for individuals with and without SMI: patients with SMI are in particular more likely to have less treatment combinations and less targeted therapy but more invasive care than patients without SMI, while diagnoses and post-treatment follow-up processes are not guideline-concordant. These results highlight the need for further studies on the mechanisms preventing equity of physical healthcare in this population and provide avenues on where to focus efforts in future interventions and practice aiming to improve the quality of cancer care for patients with SMI.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796024000234.

Availability of data and materials

This study used data from the SNDS database, which can under no circumstances be shared according to French law. Aggregated data can be made available by the corresponding author upon request.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Ibtissem Ben Dridi, Delphine Moreau, Sylvie Morel and Aurélien Troisoeufs, in charge of the qualitative phase of the research, for enriching exchanges that fuelled this manuscript. The authors would also like to thank Marie-Odile Safon and Véronique Suhard for their help with the literature review. Finally, the authors are grateful for the comments received during the Oncolille workshop on cancer screening held in Lille (France) in June 2023 as well as during the 15th IHEA World Congress on Health Economics held in Cape Town (South Africa) in July 2023.

Financial support

This research was funded by the French National Cancer Institute, grant number SHSESP19-028.

Competing interests

The funder had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results. Members of the French National Cancer Institute participating in this research are not part of the funding department of this institute and were not involved in the funding decision.

Ethical standards

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with ethical standards; they only have access to fully pseudonymized SNDS data under strict data-protection protocols and are exempt from obtaining ethical authorization and patient consent according to French law (https://www.legifrance.gouv.fr/jorf/id/JORFTEXT000043715694).

The authors adhere to the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines for case–control studies (Supplementary Table S2).