Introduction

Gambling marketing and advertising have become a frequent presence in UK life since their widespread legalization in 2007 (Cassidy, Reference Cassidy2020; Davies, Reference Davies2022; Orford, Reference Orford2019; Torrance, John, et al., Reference Torrance, John, Greville, O’Hanrahan, Davies and Roderique-Davies2021; Torrance, Roderique-Davies, et al., Reference Torrance, Roderique-Davies, Thomas, Davies and John2021). This increase in the visibility of gambling has been particularly pronounced around the national sport, soccer (McGee, Reference McGee2020; Roderique-Davies et al., Reference Roderique-Davies, Torrance, Bhairon, Cousins and John2020; Sharman, Reference Sharman2020). Some research has documented the saturation of gambling logos on the shirts and pitchside billboards in the highest levels of domestic club men’s professional soccer, in the English Premier League and the Championship (Bunn et al., Reference Bunn, Ireland, Minton, Holman, Philpott and Chambers2018; Cassidy & Ovenden, Reference Cassidy and Ovenden2017; Purves et al., Reference Purves, Critchlow, Morgan, Stead and Dobbie2020; Sharman et al., Reference Sharman, Ferreira and Newall2019; Reference Sharman, Ferreira and Newall2022). This is less of an issue with international soccer, where shirts do not commonly display sponsorship logos, and where gambling marketing bans in many countries restrict the extent to which gambling brands are visible on pitchside billboards. Instead, major international tournaments such as the World Cup are in the UK associated more strongly with gambling adverts shown during breaks in televised broadcasts (Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Davies and Sweney2018; Newall, Reference Newall2015; Newall, Thobhani, et al., Reference Newall, Thobhani, Walasek and Meyer2019), as well as marketing across other channels such as social media (Houghton et al., Reference Houghton, McNeil, Hogg and Moss2019; Houghton & Moss, Reference Houghton and Moss2020; Reference Houghton and Moss2022). This saturation of televised gambling adverts perhaps peaked over the 2018 World Cup, where over 90 min of gambling adverts were shown over the course of programming for the tournament on the commercial broadcaster ITV (Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Davies and Sweney2018).

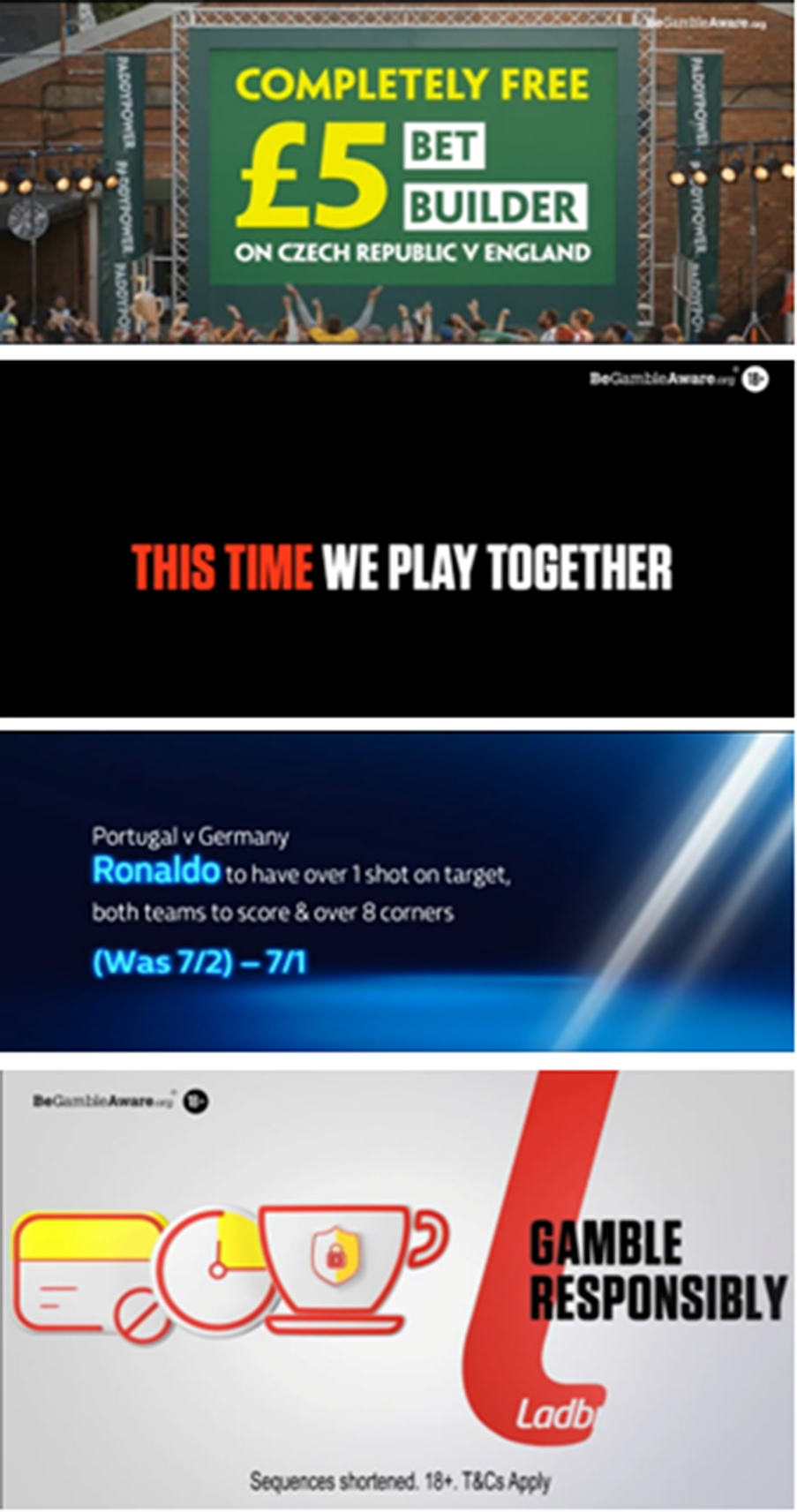

Figure 1. Examples of: financial inducement (© 2021 Paddy Power), brand awareness (© Ladbrokes), odds (© William Hill), and safer gambling (© Ladbrokes) adverts.

This increased salience of televised gambling advertising in 2018 led to increasing political pressure for change (Hymas, Reference Hymas2018), which in turn led to voluntary action from the gambling industry. The “whistle-to-whistle” ban announced in December 2018 was a voluntary agreement to not show gambling adverts for a period 5 min prior to, to 5 min after, a live sporting event (Conway, Reference Conway2018). Although first appearing a decisive move, further consideration of this announcement revealed a number of its limitations. Two limitations might be particularly relevant to the present research. First, televised sporting events can be shown with significant amounts of pre-event buildup and post-event analysis, and gambling adverts can be shown for most of these periods. And second, the ban only acts until 9 pm. Euro 2020 (rescheduled to 2021 because of the COVID-19 pandemic) was the first international men’s soccer tournament played after the whistle-to-whistle ban came into effect. The present research therefore seeks to record and present the frequency of gambling advertising shown over this tournament via the commercial broadcaster ITV (the BBC does not show commercials as a part of its programming), as one way of assessing the whistle-to-whistle ban. While research on UK gambling advertising prior to the ban has tended to focus only on the commercial breaks shown immediately around the match itself (Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Davies and Sweney2018; Newall, Thobhani, et al., Reference Newall, Thobhani, Walasek and Meyer2019), the present research investigated advertising over the entire course of relevant programs.

Previous research has also indicated distinct categories of gambling advertising content (Killick & Griffiths, Reference Killick and Griffiths2022; Newall, Moodie, et al., Reference Newall, Moodie, Reith, Stead, Critchlow, Morgan and Dobbie2019). Many adverts contain offers of financial inducements, that are, unique bonuses, boosted odds, or free bets that are not normally available to customers. It is important to track the frequency and particular content of financial inducements, given previous research linking them to ongoing gambling behavior (Balem et al., Reference Balem, Perrot, Hardouin, Thiabaud, Saillard, Grall-Bronnec and Challet-Bouju2021; Browne et al., Reference Browne, Hing, Russell, Thomas and Jenkinson2019; Hing et al., Reference Hing, Sproston, Brook and Brading2016; Reference Hing, Russell, Li and Vitartas2018; Reference Hing, Russell, Thomas and Jenkinson2019). Other adverts contain the odds on specific bets in an upcoming or ongoing sporting event, for example, “Harry Kane to score the first goal, 2-to-1.” This is also a relevant category of advertising to track, as previous research indicates that this advertising has skewed toward increasingly complex odds, containing many events, with corresponding long odds, for example, “Harry Kane to score the first goal, England to win 3-1, and three or more yellow cards, 50-to-1” (Newall, Thobhani, et al., Reference Newall, Thobhani, Walasek and Meyer2019). These complex long-odds bets can have high corresponding average losses for bettors (Newall, Walasek et al., Reference Newall, Cassidy, Walasek, Ludvig and Meyer2020), or be especially appealing to bettors (Rockloff et al., Reference Rockloff, Browne, Russell, Hing and Greer2019). Next, although this category of advertising has been subject to less previous research, our own experiences of watching soccer as fans has made us aware of some adverts solely mentioning a given operator’s safer gambling features. A high prevalence of this type of advert could counteract potential negative consequences of other types of gambling advert, although this has not to the best of our knowledge been empirically assessed. Finally, previous research has called other adverts which merely inform viewers about a particular gambling operator, without specifically mentioning other features discussed above, have been termed “brand awareness” adverts (Newall, Moodie, et al., Reference Newall, Moodie, Reith, Stead, Critchlow, Morgan and Dobbie2019). The present research therefore investigates the frequency of each of these categories of gambling advert.

Gambling adverts also typically contain safer gambling messages (Davies et al., Reference Davies, Collard, McNair and Leak-Smith2022). At the time that the men’s EURO 2020 tournament aired, the main UK safer gambling message was “when the fun stops, stop” (van Schalkwyk et al., Reference van Schalkwyk, Maani, McKee, Thomas, Knai and Petticrew2021), as the new message “take time to think” was unveiled only a few months later in October 2021 (Newall, Hayes, et al., Reference Newall, Hayes, Singmann, Weiss-Cohen, Ludvig and Walasek2022). We thought it was important to track the prevalence of the “when the fun stops, stop” message, as previous research has indicated its prevalence in other forms of UK gambling marketing (Critchlow et al., Reference Critchlow, Moodie, Stead, Morgan, Newall and Dobbie2020), as well of its lack of beneficial effect on concurrent gambling expenditure (Newall, Weiss-Cohen, et al., Reference Newall, Weiss-Cohen, Singmann, Walasek and Ludvig2022).

The present research was therefore conducted to achieve the following aims:

-

1. Record the frequency of gambling advertising shown on UK commercial television during the Euro 2020 men’s soccer tournament.

-

2. Record the proportion of advertising focusing on particular types of gambling advertising, specifically advertising featuring financial inducements, odds, safer gambling features, and those focused on raising brand awareness.

-

3. Record the proportion of adverts featuring the “when the fun stops, stop” safer gambling message.

Method

Open practices

The data underlying this study, including a narrative summary of each advert’s theme and key offer, and screenshots of the key offer, are available at https://osf.io/zfk3y/.

Euro 2020

The UEFA Euro 2020 tournament involved 51 football matches, which were all shown on UK terrestrial television. However, 24 matches were only shown on the noncommercial broadcaster, the BBC, which does not run advertising breaks, and so will not be analyzed here. Of the remaining 27 matches shown on ITV, the recording of two matches on the educational rewatching service Box of Broadcasts were corrupted (Sweden vs. Poland and Belgium vs. Portugal), and so could not be included in the present analysis. The final sample size therefore comprises 25 matches.

Adverts were coded from the first advertising break shown after the match program had started, which occurred around 12–16 min after the program started. Adverts were coded until the last advertising break shown before the match program finished.

Coding process

The following aspects of each gambling advert were recorded during the initial round of data extraction by CF:

Advert number: Cumulative number given to each advert across the data extraction table and associated photo screenshot.

Match: The two teams who were playing when the advert was broadcasted.

Company: Which gambling operator showed the advert?

Segment number: Where the advertising break was relative to the game: before kickoff (1), shown before the final whistle (2), and shown after the match’s final whistle, including the conclusion of any extra time or penalties (3).

Time of advert: The total number of minutes and seconds that the match program had been playing when the advert began broadcasting.

Program time of kickoff: The total number of minutes and seconds of the match program that the match’s kickoff happened at.

Program time of final whistle: The total number of minutes and seconds that the match program has been playing at the time of the match’s final whistle.

Program duration: The total number of minutes and seconds that the program showing the match lasted for.

Summary: A narrative summary of the adverts based on the relevant visual, emotional, and sound features. When there were pertinent features such as a celebrity or shouting, all these features were described. Following previous research (Newall, Thobhani, et al., Reference Newall, Thobhani, Walasek and Meyer2019), the advert’s “key offer” was recorded verbatim, and this is supported by a photo screenshot.

Safer gambling message: The duration and content of any safer gambling message shown were recorded. This feature was then used to deduce the rate at which the “when the fun stops, stop” message was used (Newall, Weiss-Cohen, et al., Reference Newall, Weiss-Cohen, Singmann, Walasek and Ludvig2022).

The coder watched each match program three times to ensure accuracy.

After this initial stage of data extraction, an additional stage of content analysis was performed where each advert’s key offer was categorized as one of the following:

Financial inducement: An advert offering some unique financial offer to bet, not normally available, such as a free bet or a refund if a bet were to lose (Newall, Moodie, et al., Reference Newall, Moodie, Reith, Stead, Critchlow, Morgan and Dobbie2019).

Odds: An advert featuring the odds on one or more specific bets, for example, “Harry Kane to score first, 3-to-1.” If a given set of odds are advertised as being boosted or otherwise higher than they would be Newall, Thobhani, et al. (Reference Newall, Thobhani, Walasek and Meyer2019), this advert’s key offer would still be coded as odds advertising, and not a financial inducement.

Safer gambling: An advert that primarily talks about an operator’s range of safer gambling tools, and not other offers such as a financial inducement or currently available betting odds.

Brand awareness: An advert that primarily reminds viewers about the existence of the gambling operator (Newall, Moodie, et al., Reference Newall, Moodie, Reith, Stead, Critchlow, Morgan and Dobbie2019), and not other types of advertising as defined above.

Reliability checks

Two researchers independently coded each extracted advert with respect to one of these four categories (PN and CF). There was only one disagreement (99.1% agreement rate), suggesting a satisfactory level of intercoder agreement. The one disagreement was resolved after a round of discussion. Additionally, the two coders were in complete agreement on determining whether each advert featured the “when the fun stops, stop” safer gambling message or not, based on the summary provided by CF.

Results

Six gambling operators showed adverts during the tournament. Overall, 113 gambling adverts were recorded over 25 matches, equal to a rate of 4.5 gambling adverts per match. Across these 113 adverts, we detected 14 distinct adverts overall, which differed either in terms of the narrative summary of the advert, or which differed in terms of their key offer (e.g., a free initial £5 bet or a free bet after a losing bet).

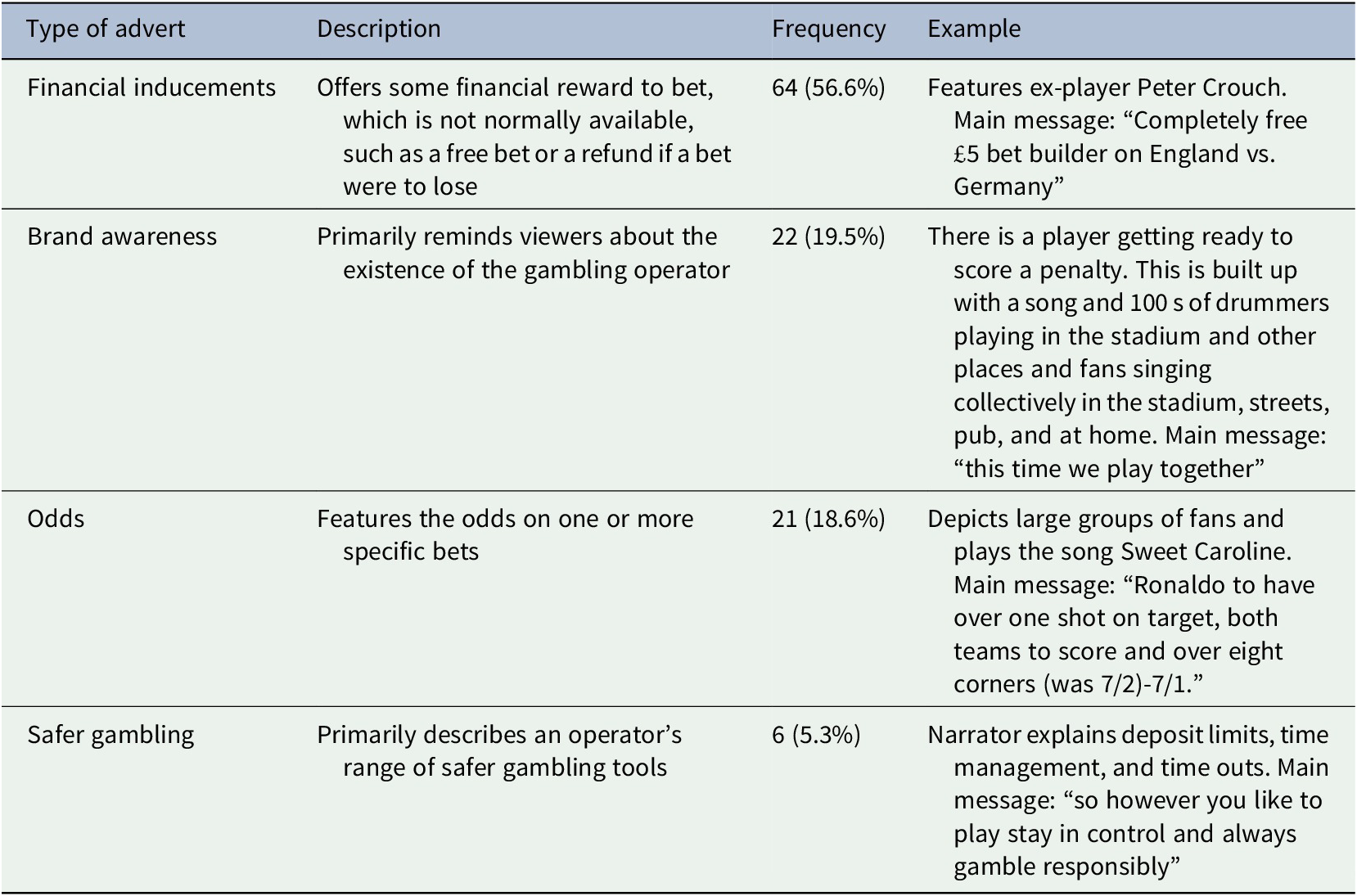

Table 1 provides a summary of the main findings. Out of the four advert categories, financial inducements were shown the most frequently (64 adverts; 56.6%), and were shown by four different gambling operators. These financial inducements were varied, with some operators providing £5 free bets, either as a matched bet based on the customer making a £5 bet, on specific matches, via specific sports betting products (“bet builders”), or after making a specific number of bets (three). Other adverts in this category did not mention a specific inducement, only that one inducement would be provided for future Euro 2020 matches. Another advert offered a free bet if a complex bet provided a “near-miss” outcome, where all but one aspect of the bet occurred. Another advert mentioned an improvement in the operator’s standard terms and procedures around the “cash-out” feature in in-play betting.

Table 1. Summary of findings

Brand awareness adverts were the next most frequently shown category (22 adverts, 19.5%), and were shown by four operators. As is consistent with how this category of advert was operationalized by us, this advert did not feature any key offers. Instead, they tended to invoke themes of togetherness and sociability, and appeared to attempt to tap into the national mood around international soccer tournaments. For example, one operator used the song “Sweet Caroline,” which is frequently played around England matches. In addition, operators used messages such as, “It’s who you play with,” and “this time we play together.”

Overall, 21 odds adverts were shown (18.6%), but shown only by one operator. These odds adverts all showed one varying complex bet for an upcoming match, with odds that had recently been boosted, such as, “Spain to win, over 9 corners & over 3 cards in the match (was 4/1)-8/1,” or “Lukaku to score, Mertens to have a shot on target & over 9 corners (was 7/2)-7/1.”

Safer gambling adverts were the least frequently shown over the four categories, appearing six times (5.3%), and being shown by three operators. These adverts mentioned specific safer gambling tools, such as deposit limits and time-out limits.

The “when the fun stops, stop” safer gambling message was observed 64 times, meaning that it was shown in 56.6% of adverts. The presentation of this message varied, with some presentations using a version of the message where the word “fun” is shown in a larger font than the rest of the text, and other presentations where all of the words were in the same font size. The message was also shown for varying amounts of time, with some presentations being a rapid display across the entire screen at the end of the advert, and some presentations showing the message at the bottom of the screen throughout the advert. Given this range of presentation styles, the exact frequency of each present style was not recorded here.

Discussion

This research investigated the frequency and content of gambling advertising shown during the Euro 2020 men’s soccer tournament, which was played in 2021 due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The tournament was the first televised international men’s soccer tournament occurring after the UK gambling industry’s “whistle-to-whistle” ban came into effect. An average of 4.5 adverts were shown during each relevant match, suggesting that a viewer who watched the entirety of each program would still view over 100 gambling adverts across the span of the tournament, despite the ban. Furthermore, a majority of these adverts could be categorized and compared against previous research on gambling advertising themes. Financial inducements were the most frequently shown category, and provided a range of specific offers, which were similar to the specific offers seen before in previous research (Newall, Moodie, et al., Reference Newall, Moodie, Reith, Stead, Critchlow, Morgan and Dobbie2019). Brand awareness adverts were the next most frequently shown category, and highlighted themes of togetherness and familiarity that have also been observed in previous research (Lopez-Gonzalez et al., Reference Lopez-Gonzalez, Guerrero-Solé and Griffiths2018). Odds advertising was the third most frequently shown category, at a frequency of slightly less than one advert shown per relevant match, and by only one operator. Although the types of “complex” odds shown were similar to those that have been observed in previous research, the frequency of this type of advertising was lower than it was in the 2018 World Cup, when 2.2 of these adverts were shown on-average per-relevant match (Newall, Thobhani, et al., Reference Newall, Thobhani, Walasek and Meyer2019). Overall, this decrease in the frequency of odds advertising may have partly been due to the whistle-to-whistle ban, as these adverts may be especially interesting to viewers when shown either immediately before or during a match. Safer gambling adverts were still a new and emerging category of gambling advert during Euro 2020, with only six of these adverts being observed over the whole tournament. Finally, all adverts contained at least some kind of safer gambling message shown on-screen, with the “when the fun stops, stop” message shown during a majority of matches, a rate of using this message which compares to previous research on other forms of gambling marketing (Critchlow et al., Reference Critchlow, Moodie, Stead, Morgan, Newall and Dobbie2020).

A fuller picture of the whistle-to-whistle ban can perhaps be achieved by looking at where gambling adverts tended to appear in terms of the overall programs. A large majority of adverts (93; 82.3%) were observed prior to kick-off, with a much smaller number (18; 15.9%) happening after the final whistle. Viewers wishing to watch international soccer matches, but without seeing gambling adverts, could perhaps be recommended to particularly avoid advertising breaks in the lead-up to matches. Finally, we only observed two adverts shown during the match, and these occurred after the 90 min of play and were shown immediately before a period of extra time. Because of how the whistle-to-whistle ban has been designed, half-time gambling adverts can potentially occur for matches kicking-off at 8 pm or later, as the adverts in this break are then shown after the 9 pm watershed for the ban. The appearance of adverts during the half-time break has been observed more commonly in club European games, which commonly kick-off in the 8 pm slot (Footballapp.com, n.d.). Although this limitation of the whistle-to-whistle ban was rarely utilized during Euro 2020, future research should further investigate matches kicking-off at 8 pm or later.

These findings are subject to various limitations. The present research cannot investigate these adverts’ effect on behavior, which is a crucial debated issue in gambling marketing research (Wardle et al., Reference Wardle, Critchlow, Brown, Donnachie, Kolesnikov and Hunt2022). For example, some adverts mentioned specific products such as “bet builders” which are especially popular with disordered gamblers (Newall, Cassidy, et al., Reference Newall, Walasek, Vázquez Kiesel, Ludvig and Meyer2020), but the present research could not compare effects across the different categories of adverts observed here. The present research was performed retrospectively via Box of Broadcasts, and the two resultant missing matches suggest that gambling researchers should also prospectively obtain their own recordings of matches to ensure complete coverage. The research could also not investigate the frequency or content of other types of marketing, such as social media marketing, which may become increasingly important due to legislative changes and behavioral changes among soccer fans (Rossi et al., Reference Rossi, Nairn, Smith and Inskip2021). The sponsorship of televised soccer broadcasts by gambling operators is another action which is unaffected by the whistle-to-whistle ban, and which may therefore become increasingly prevalent, although the present research did not investigate this issue. Finally, previous research into gambling advertising on UK television has either been limited by looking at smaller time-windows around the match itself (Duncan et al., Reference Duncan, Davies and Sweney2018), or only looking at specific types of adverts, such as odds advertising (Newall, Thobhani, et al., Reference Newall, Thobhani, Walasek and Meyer2019). This has limited the extent to which the present findings can be compared against previous tournaments. The tournament itself was delayed due to the COVID-19 pandemic, an event which may have had unique impacts on gambling marketing (Critchlow et al., Reference Critchlow, Hunt, Wardle and Stead2022).

Gambling advertising remained a significant part of the Euro 2020 men’s soccer tournament TV viewing experience in the UK, despite the whistle-to-whistle ban. The types of messages shown in these adverts stayed largely similar to the types that have been observed in previous research, with only six (5.3%) novel safer gambling adverts observed over the sample.

Acknowledgments

None.

Copyright notice

The authors acknowledge that the copyright of all screenshots used in Figure 1 are retained by their respective copyright holders. The authors use these copyrighted materials for the purposes of research, criticism or review under the fair dealing provisions of copyright law in accordance with Sections 29(1) and 30(1) of the UK Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Open peer review

To view the open peer review materials for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/exp.2022.26.

Data availability statement

The data are available at https://osf.io/zfk3y/.

Authorship contributions

P.W.S.N., C.A.F., and S.S. conceived and designed the study, and wrote the article. C.A.F. conducted data gathering. P.W.S.N. performed the statistical analysis.

Funding statement

This article received no funding.

Conflict of interest

P.W.S.N. is a member of the Advisory Board for Safer Gambling—an advisory group of the Gambling Commission in Great Britain, and in 2020 was a special advisor to the House of Lords Select Committee Enquiry on the Social and Economic Impact of the Gambling Industry. In the last 3 years, P.W.S.N. has contributed to research projects funded by the Academic Forum for the Study of Gambling, Clean Up Gambling, Gambling Research Australia, NSW Responsible Gambling Fund, and the Victorian Responsible Gambling Foundation. P.W.S.N. has received open access fee grant income from Gambling Research Exchange Ontario (GREO). S.S. has received funding in the last 3 years from the Society of the Study of Addiction (SSA), and the King’s Prize Fellowship funded by the Wellcome Trust. He is also a current UKRI Future Leaders Fellow, which funds his research at King’s College London. Additionally, S.S. is part of the Current Advances in Gambling Research conference committee (CAGR), which was funded by the SSA, GREaT Wales, and GREO (Canada). He has also received honoraria from GREO as part of the Academic Forum for the Study of Gambling, and from Taylor Francis Publishers for editorial work. The remaining author has no conflicts to declare.

Comments

Comments to the Author: This is a review of the manuscript entitled “The frequency and content of televised UK gambling advertising during the men’s 2020 Euro soccer tournament” for consideration for publication in the journal Experimental Results.

Before I started the review I asked for clarification to the editorial office because the paper does not describe an experiment per se. The platform requires me to answer three questions about the use of controls, the experimental methods and the reporting of experimental data. I can only answer yes or no, and I miss a “not applicable” category here. Although the editorial office’s response was not entirely clarifying (they simply copy-pasted the aims section of the journal’s website) I accepted the submission as a candidate for publication.

The paper deals with the effects that the voluntary whistle-to-whistle gambling adverting ban has had on the exposure of UK fans to gambling stimuli.

This is an extremely simple paper, but well written and with a clear and cohesive argument. The coding procedure is straightforward. Testament to that is that the disagreement between coders was almost non-existent (99.1% agreement).

The results are presented in a very simple manner as well, in the form of raw percentages. The paper concludes that, although the matches abided by the whistle-to-whistle stipulations, the spectators still received around 4 to 5 gambling stimuli per match. This means the law is not entirely effective in procuring a gambling-free sport watching experience.

Background materials can be found at OSF repository, which is always a good practice to increase transparency and replicability.

I am not familiarized with the scope and quality of Experimental Results. As far as I can tell, this paper has no flaws, it reads well, and I cannot suggest any changes to improve it. The aims and methods of the paper are very basic but correct. In any case, from the response of the editorial office, I understand this journal publishes such research documents. Therefore, my recommendation is to publish it in its current form.