I. Introduction

Ever since its foundation, the workings of the United Nations Human Rights Commission and of its successor, the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC), have been characterised by a struggle between actors who have promoted the implementation of transversally valid, universal human rights standards on the one hand, and actors who have argued that human rights have to be realised – and thus relativised – according to specific religious, cultural, and political contexts on the other.Footnote 1 ‘Universalists’ and ‘contextualists’Footnote 2 battle over the right interpretation and global implementation of human rights. Universalists promote the active inclusion of all individuals and causes subject to potential human rights violations that have hitherto not been addressed in a specific human rights language: women, children, LGBTQ, disabled persons, and other marginalised and stigmatised groups. Contextualists argue against the universal application of ever more detailed definitions of human rights and their potential violations. They refer to religious, cultural and historical traditions as legitimate sources of norms governing a society and advocate a restrictive application of human rights law. Both universalists and contextualists make an active use of the UN’s human rights discourse and its procedures and institutions, but contextualists do so with a restrictive purpose that is diametrically opposed to the cause of universalist advocates of human rights and, arguably, the UN bureaucracy itself. The contextualists’ cause is therefore frequently interpreted by universalist critics as an attack on and backlash against human rightsFootnote 3. Despite the fact that contextualist arguments are rooted in an intra-Western debate,Footnote 4 the human rights sceptical view is mostly associated with African, Asian and Middle Eastern countries (the ‘Global South’), whereas universalist position are prima facie associated with Western liberal democratic countries.

The universalist–contextualist debate arguably renewed intensity in 2009, when the United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC) launched discussions of a set of resolutions on the topic of ‘traditional values’.

The leader of this discussion was the Russian Federation, which acted as the chief promoter of the resolution ‘Promoting human rights and fundamental freedoms through a better understanding of traditional values of humankind’.Footnote 5 The initiative gathered majority support among non-Western countries. In 2014, a resolution on ‘Protection of the family’ set off a chain of activities in the footsteps of the ‘Traditional values’ resolution.Footnote 6 This resolution was, once again, co-initiated and supported by the Russian Federation, which, as before, could rely on a large circle of supporters among non-Western countries. This article is dedicated to the analysis of the traditionalist agenda and the ‘Protection of the family’ resolution in particular as the latest instance of the universalist–contextualist standoff in the UNHRC. Throughout the article, the term ‘traditionalist agenda’ is used to designate a specific set of ideas, meanings, and categories regarding the social-historical conditions of emergence of the international human rights regime and its contemporary application and relevance, as they emerge from the aforementioned resolutions and related documents across all three levels of UN governance, involving states’ diplomats, UN bodies, and global civil society.Footnote 7

The Russia-led traditionalist agenda could be interpreted as yet another chapter of contextualist opposition to the universalist application human of rights and as a successor to the cultural relativism in human rights promoted in the past by the Organization of Islamic States or countries from the Global South.Footnote 8 This article seeks to challenge such an interpretation and, instead, to deepen the observation made by McCrudden that the traditionalist agenda has novel political aspects.Footnote 9 We follow McCrudden’s observation that the resolutions on ‘Traditional values’ and ‘Protection of the family’ in the UNHRC are reactive to recent developments in international human rights practice in ways that earlier debates were not. According to McCrudden, the resolution on ‘Traditional values’ addressed questions of whether human rights primarily applied to actions by the state or also by non-state actors, whether human rights imposed mostly negative obligations on the state or also positive obligations, and whether human rights primarily related to the protection of civil and political rights or also to rights found in the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.Footnote 10 The resolution on ‘Protection of the family’, on which our focus lies in this article, targeted mainly one development pointed out by McCrudden, namely the fact that international human rights have increasingly touched ‘private’ areas such as sexual morality and intra-family relations that were formerly considered inappropriate for international intervention and were within the sphere of national sovereignty. The traditionalist agenda firmly rejects gay marriage, which is increasingly becoming a norm in Western countries, and both the ‘Traditional values’ resolution and the ‘Protection of the family’ resolution must be interpreted as attempts to stop legal advancements in questions of sexual orientation and gender identity.

This article makes the argument that the Russian traditionalist agenda at the UNHRC represents a form of illiberal norm protagonism in the human rights sphere that deserves renewed attention, despite apparent continuities. The Russian agenda at the UNHRC exemplifies a more general argument made by Lauri Mälksoo about Russian approaches to international law, namely that Russia and liberal Western states do not share the same philosophical foundations in their understanding of international law.Footnote 11 What this article adds to his argument is that Russia’s normative challenge to the international legal order – because it finds positive resonance in the West – lays open existing fragmentations in international human rights law along ideological rather than national or civilisational lines.

In order to answer the question of how the Russian traditional values initiative has become so successful, this article undertakes an in-depth analysis of the discourse coalitions of both supporters and opponents of the traditionalist agenda, using the tools of discourse analysis in international relationsFootnote 12 and drawing on a constructivist approach to norm diffusion in international organisations.Footnote 13 The discourse analysis shows that the traditionalist agenda employs two distinct argumentative strategies: first, it taps into the conceptual shift introduced by liberal multicultural and postcolonial human rights theories, according to which a contextualist understanding of human rights is more progressive than the universalist vision.Footnote 14 Second, it politicises international human rights law and practice by developing its own counter-narrative of what human rights were in the past and should be in the present in order to oppose liberal human rights law and delegitimise Western states and even the UN bureaucracy itself. These two strategies allow the traditionalist agenda to present itself as transversal and progressive and to denounce, in turn, the Western, liberal view of human rights as sectarian and backward. This article observes that the traditionalist agenda thereby puts Western liberal actors on the defensive. Some countries and in particular some religious NGOs are pushed into a ‘double bind’ communicative situation in which they are confronted with two legitimate but conflicting demands, each of which can be fulfilled only by forfeiting the other.

The material core of the article is an in-depth analysis of all documents related to the resolutions ‘Promoting human rights and fundamental freedoms through a better understanding of traditional values of humankind’ and ‘Protection of the family’. The analysed documents include 195 texts, among them 68 texts on ‘Traditional values’ and 127 on ‘Protection of the family’ (see Appendix 1). These texts include the resolutions themselves, summaries of workshops on the topics, and submissions from countries and NGOs that were received as part of the discussion process. The texts cover the period from 2009 to 2016. We have visualised the quantitative data of this analysis (using R) in order to graphically show the results of voting and NGOs’ submissions. Our qualitative analysis of the texts was aimed at identifying arguments along the ideological division of universalist versus contextualist approaches. In addition, when undertaking the qualitative analysis, we draw on insights provided by five interviews with actors from all three levels of UN governance (one UN expert, two NGO representatives, and two national diplomats, respectively).

II. The origins of the Russia-led traditionalist agenda in the human rights discourse of the Russian Orthodox Church

The ‘Traditional values’ resolution promoted by the Russian Federation in the UNHRC has its origin in the Russian Orthodox Church’s discourse on human rights, in particular in, as Stoeckl has shown,Footnote 15 the Church’s interpretation of Article 29 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which places emphasis on duties and ‘just requirements of morality’.Footnote 16 The Russian Orthodox Church read Article 29 as legitimisation of the argument that contextual parameters constitute guiding norms for the interpretation of human rights. This re-grounding of contextualist arguments in human rights instruments themselves has arguably set in motion a new dynamic in the universalist–contextualist debate. Contextualists today present themselves as more in line with the original intention of the Universal Declaration than contemporary progressive promoters of human rights. Consider the following statement by then-Metropolitan and head of the External Relations Department of the Moscow Patriarchate (and now the current Patriarch of the Russian Orthodox Church) Kirill as an illustration of this ‘universalisation’ of the contextualist viewpoint:

I am convinced that the concern for spiritual needs, based moreover on traditional morality, ought to return to the public realm. The upholding of moral standards must become a social cause. It is the mechanism of human rights that can actively enable this return. I am speaking of a return, for the norm of according human rights with traditional morality can be found in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948.Footnote 17

What the Patriarch of Moscow presented in this statement is what the discourse coalition approach calls ‘a story line’: a narrative ‘in which elements of the various discourses are combined into a more or less coherent whole and the discursive complexity is concealed’.Footnote 18 The Patriarch’s statement, in fact, makes a striking claim: he interprets human rights not in an individual, but in a social and public light. The focus lies not on how human rights protect individuals, but how they enable them to do certain things. The Patriarch wants to set a limit to the enabling side of human rights. This limit is defined, in his words, by ‘traditional morality’. The Universal Declaration, which the Patriarch cites as his source here, does not contain the term ‘traditional morality’; it speaks instead of ‘just requirement of morality … in a democratic society’. In other words, the Universal Declaration indeed envisions limits for human rights, but these limits are understood as the fruit of a democratic process. The Patriarch twists the meaning of Article 29 when, by using ‘traditional morality’, he seals public morality off from change through democratic deliberation, preferring instead past practice and traditional mores as sources of legitimacy.

It is precisely this argument that stands behind the traditionalist agenda promoted by Russia within the UNHRC. This traditionalist agenda before the UNHRC has mobilised a stable coalition of supporters from among non-Western UN member states, and has been met with opposition from Western countries and UN agencies. At the same time, it has acquired considerable support from conservative, mostly Christian civil society actors in the West. In the discussion under scrutiny here, these groups form discourse coalitions,Footnote 19 which then battle over questions of what human rights should be and do. The traditionalist coalition has prevailed in all of the UNHRC resolutions discussed in this article, and as a result, the liberal egalitarian human rights position of Western states has been turned into a minority opinion.

III. ‘Traditional values’ and ‘Protection of the family’ in the UNHRC

Between 2009 and 2013 and between 2014 and 2017, two traditionalist causes were debated at the UNHRC, the first being the resolution on ‘Traditional values’, the second the resolution on ‘Protection of the family’. In this section, we give an outline of each of these debates and in the following section, we analyse their content and the strategies used.Footnote 20

Traditional values

The resolutions, seminars, reports, and submissions connected to ‘Promoting human rights and fundamental freedoms through a better understanding of traditional values of humankind’ span a period from 2009 until 2013, and a total of 6 UN documents and 62 submissions. The first resolution 12/21 was presented by the representative of the Russian Federation to the Human Rights Council, Valery Loshchinin, and it requested ‘to convene, in 2010, a workshop for an exchange of views on how a better understanding of traditional values of humankind underpinning international human rights norms and standards can contribute to the promotion and protection of human rights and fundamental freedoms’.Footnote 21 This resolution was adopted against the votes of the Western countries and, one year later, on 4 October 2010, the requested workshop entitled ‘Traditional Values and Human Rights’ took place at the United Nations Commission on Human Rights in Geneva. The press service of the Moscow Patriarchate reported extensively on the workshop and the preceding resolution, presenting it as the outcome of Kirill’s address to the General Assembly of the United Nations in March 2008.Footnote 22 Among the participants at this workshop was Igumen Filip Ryabykh, representative of the Moscow Patriarchate in Strasbourg. In his speech at the seminar he expressed the view that religious views on matters of human rights should be taken into account in the development and establishment of international human rights standards in order to counteract efforts to promote a ‘new generation of human rights’ such as ‘the right to sexual orientation, euthanasia, abortion, experimentation with human nature’.Footnote 23 ‘It is about time that the ideological monopoly in the sphere of human rights is over,’ he said and added: ‘… from the point of view of democracy, it is important to provide an opportunity for representatives from different philosophical and moral views to participate in the development of the institution of human rights’.Footnote 24

In March 2011, the Human Rights Council again adopted a resolution entitled ‘Promoting human rights and fundamental freedoms through a better understanding of traditional values of humankind’.Footnote 25 Resolution 16/3 affirms that ‘dignity, freedom and responsibility are traditional values’. It also notes ‘the important role of family, community, society and educational institutions in upholding and transmitting these values’. Resolution 16/3 contained the request to the Human Rights Council Advisory Committee to prepare a study on how a better understanding and appreciation of traditional values could contribute to the promotion and protection of human rights, and to present that study to the Council before its 21st session.

By the time the 21st session started in September 2012, the study had not been finished, but the rapporteur for the report presented a ‘preliminary study’Footnote 26 and tabled a new resolution, entitled ‘Promoting human rights and fundamental freedoms through a better understanding of traditional values of humankind: best practices’.Footnote 27 Resolution 21/3 stated that the Human Rights Council remained seised on the matter of traditional values, it took note of the fact that the Advisory Committee was in the process of preparing the aforementioned study on the topic, and it requested an additional study with the aim of ‘collect[ing] information from States Members of the United Nations and other relevant stakeholders on best practices in the application of traditional values while promoting and protecting human rights and upholding human dignity’. In response to this resolution, the advisory committee received 60 submissions between January and March 2013 from stakeholders (countries, NGOs and UN agencies) (see Appendix 1). The advisory committee presented its ‘Study of the Human Rights Council Advisory Committee on promoting human rights and fundamental freedoms through a better understanding of traditional values of humankind’Footnote 28 on 6 December 2012. The chain of activities on ‘Traditional values’ ended in 2013 with the publication of the ‘Summary Information from States Members of the United Nations and Other Relevant Stakeholders on Best Practices in the Application of Traditional Values while Promoting and Protecting Human Rights and Upholding Human Dignity’.Footnote 29 We analyse the content of these submissions and resolutions below.

Protection of the family

At the 26th Session of the UNHRC on 25 June 2014, the Council was asked to vote on Resolution 26/11, entitled ‘Protection of the family’.Footnote 30 The Resolution, which was presented by a group of countries including Egypt and Russia, set forth a general aim to ‘strengthen family-centered policies and programs as part of an integrated, comprehensive approach to human rights’. In the Resolution, it was stated that ‘the family has the primary responsibility for the nurturing and protection of children’, that family is ‘the fundamental group unit of society and entitled to protection by society and the State’, and that the UNHRC should convene a panel discussion and prepare a report.

A group of countries that included the US and Western European states tabled an amendment emphasising that ‘in different cultural, political, and social systems, various forms of the family exist’. This amendment was not discussed after Russia brought to play a ‘no/action motion’ that was adopted by a 22–20 majority. Resolution 26/11 was eventually adopted by a recorded vote of 26 to 14, with 6 abstentions.

The requested panel discussion was held on 15 September 2014 during the 27th session of the UNHRC, and a report on this discussion was published on 22 December 2014.Footnote 31 After this discussion and report, the family agenda branched out in two directions, one in view of ‘the contribution of the family to the realisation of the right to an adequate standard of living for its members, particularly through its role in poverty eradication and achieving sustainable development’Footnote 32 and on ‘the role of the family in supporting the protection and promotion of human rights of persons with disabilities’.Footnote 33

Resolution 29/22, entitled ‘Protection of the family: contribution of the family to the realisation of the right to an adequate standard of living for its members, particularly through its role in poverty eradication and achieving sustainable development’ and adopted on 3 July 2015, offered a long list of benefits of policies and measures to protect families and encouraged states to implement such policies, and requested the High Commissioner of Human Rights to prepare a report ‘on the impact of the implementation by States of their obligations under relevant provisions of international human rights law with regard to the protection of the family’.Footnote 34 The resolution expressed ‘concern that the contribution of the family in society and in the achievement of development goals continues to be largely overlooked and underemphasized’. This resolution was adopted against the votes of the Western states (together with Japan, Korea and South Africa). The requested report was presented at the 31st session of the UNHRC on 29 January 2016.

Resolution 32/23, entitled ‘Protection of the family: role of the family in supporting the protection and promotion of human rights of persons with disabilities’ and adopted on 1 July 2016, repeated the general aims under ‘Protection of the family’, added specific observations on the situation of persons with disabilities, and requested the holding of a seminar and preparation of a report.Footnote 35 This resolution was again adopted against the votes of Western states (together with Panama and Korea). The requested seminar was held in February 2017. The entire chain of resolutions, seminars and reports from 2014 until December 2016 (the conclusion of the time period studied here) was accompanied by submissions from member states, NGOs and UN bodies, a total of 127 documents.

IV. ‘Traditional values’ and ‘Protection of the family’ in the UNHRC: Discourse coalitions

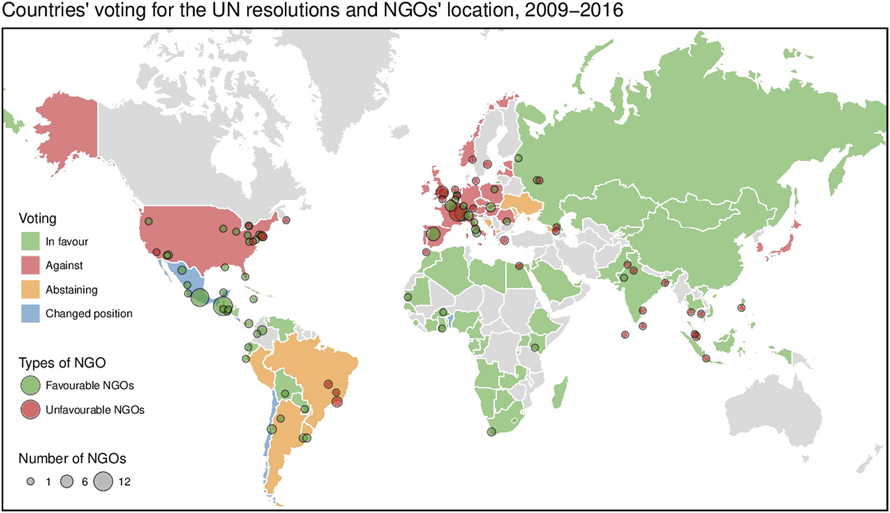

The resolutions on ‘Traditional values’ and ‘Protection of the family’ mobilised the same coalitions among the UNHRC member states. Below, a world map (Figure 1) based on the cumulative voting results of all relevant resolutions between 2009 and 2016 shows which countries supported the resolutions and which countries opposed them, and which countries changed position or abstained. In the context of this article, the focus lies on the stable coalitions, leaving aside the motives behind why some countries may have changed their positions. It becomes clear that throughout the process, during which some members in the UNHRC on rotating chairs changed, the overall geographical pattern of the coalitions remained the same. These topics mobilised support from Russia and post-Soviet states, from countries of the Organization of Islamic Cooperation, and countries in what is broadly referred to as the Global South. They met with consistent opposition from Western European countries, the United States, and few others.

Figure 1. Countries’ voting for the UN resolutions and NGOs’ location, 2009-2016

However, country voting results show only one side of the unfolding controversy at the UNHRC. The other side is the engagement of NGOs accredited to the UN. NGOs submitted statements in support or opposition to the traditionalist agenda. In the map (Figure 1), we have added all submissions mobilised between 2009 and 2016 in the context of the two sets of resolutions, in order to show that voting blocks are counterbalanced by civil society engagement that is frequently in contrast to a country’s voting behaviour.

Coalition-making over universalist–contextualist topics is, as we already pointed out in the Introduction, not a novelty in the UN context.Footnote 36 In the past, the debates on ‘Defamation of religion’Footnote 37 or ‘Dialogue of civilizations’Footnote 38 pursued similar causes. Also, the campaign and coalition for family values is not a novelty. Conservative mobilisation against topics of sexual orientation and gender identity in the human rights context goes back to 1994, when the Vatican, together with religious and non-denominational conservative NGOs and Islamic States, raised arguments about the ‘natural’ and ‘traditional family’ at the Cairo Conference on Population and Development.Footnote 39 Together with the 1995 UN Conference in Beijing, these two large UN Conferences are considered by scholars as the starting point for global activism by a Christian right network.Footnote 40

Should one therefore interpret the traditionalist–liberal standoff in the UNHRC between 2009 and 2016 as business as usual? Two aspects of the recent debate suggest that there are novel aspects to be considered. First, the new leader of this debate is Russia, supported by Muslim states and countries from the Global South; and second, the argumentative strategy employed by the traditionalist agenda has mobilised broad support among NGOs in the West and has turned a formerly contextualist topic into a transversal cause. In this section, we focus on the leadership role of Russia, before turning to the arguments employed in the next section.

Heiner Bielefeldt, former UN Special Rapporteur on Freedom of Religion, confirmed to us that Russia has taken over the leader’s position in a discussion which, ten years ago, was associated with Muslim states.Footnote 41 As a matter of fact, Muslim states are still actively involved in the traditionalist agenda, and it was Egypt, not Russia, which tabled the Resolution on the family. However, Russia appears to have been acting behind the scenes. One interviewee from the diplomatic corps of the Republic of Belarus explained to us that it was Russia who initiated the ‘Group of Friends of the Family’Footnote 42 in 2014.Footnote 43

Russia’s leadership role was corroborated by two interviewees from the NGO sector, one of which said ‘Russia is taking over. This is quite clear.’Footnote 44 Russia is taking over the traditionalist agenda not only from the Muslim states, but, as this last interviewee made clear, also from the Holy See. Interviewee C observed:

You have had the last four years a constant, a constant research by the Russians to create bridges and to gain a Holy See voice … to support some of the agenda of Russia. And with some success.Footnote 45

Several authors have already started to look into the role of the newly arrived Russian Orthodox in existing coalitions over conservative values created by Catholics, Muslims and US-based conservative Protestants;Footnote 46 our article deepens their analysis. It appears that Russia’s leadership role in the promotion of a traditionalist agenda in the UNHRC has opened a new phase in anti-liberal norm protagonism at the UN that was previously associated with Muslim states and the Holy See. The traditionalist agenda under Russian leadership has turned contextualist opposition to universalist equal application of human rights into a transversal topic on its own right. By making an appeal to transversal phenomena like ‘traditional values’ or ‘family’ and by expanding from the demands of one religion (Islam in the case of the blasphemy debates) to religions and cultures as such, the traditionalist agenda has become transversal and has mobilised support in countries whose government representatives at the UNHRC oppose the agenda. In fact, among the NGO submissions, favourable submissions between 2009 and 2016 dominated, with 65 per cent of the total.

The mobilisation pattern of pro-traditionalist NGOs in Southern and Eastern Europe, the United States, and Latin America shows widespread support for the items on the traditionalist agenda upon which country representatives took a contrary or neutral stance. In the EU and the United States, which voted against the ‘traditional values’ and ‘pro-family’ resolutions, a considerable number of NGOs mobilised in favour of this agenda. The geographical pattern of this favourable mobilisation in Europe shows that a greater number of favourable statements came from Orthodox and Catholic countries than from Protestant countries. Also in Southeast Asia NGO mobilisation is in contrast to countries’ voting behaviour, but less unexpectedly so: the literature on norm protagonism in civil society anticipates liberal civil society mobilisation as a counterbalance to authoritarian, conservative, or non-liberal governments.Footnote 47 The traditionalist agenda reverses this trend in two ways. First, it enacts a non-liberal norm protagonism rarely considered in the literature so far, and second, it mobilises and gives coherence to a traditionalist section of civil society inside liberal democratic countries. It is particularly the debate inside these countries, the EU Member States and the United States, which is in the focus of the following section.

V. Patterns of argumentation in the debate over ‘Traditional values’ and ‘Protection of the family’

The traditionalist agenda is consciously in conflict with a liberal, progressive, and expansive interpretation of international human rights law. This conflict is not new to the UN context, but what is new, this article argues, is the way in which it is framed by traditionalist actors and the effect this has on liberal democratic states and some civil society stakeholders. The text corpus on which the analysis of the traditionalist agenda and the debate generated is based comprises all the documents related to the ‘Traditional values’ and ‘Protection of the family’ resolutions (including the resolutions, panel reports, and submissions) from 2009 until 2016 (see Appendix 1). This corpus was coded in a bottom-up fashion, identifying recurring arguments and grouping these under coherent categories. From the analysis, one can derive five broad categories that define the battle over traditionalist issues at the UN. Each of these categories stands for one particular set of arguments that actors use in the debate. Each side actively and reciprocally creates arguments by challenging the other’s agenda and advancing claims.

1. Substantial arguments aim at a substantial definition of what the family is or what traditional values are.

2. Functional arguments describe the functional (social) utility and worth of the family and of traditional values or the rejection thereof.

3. Legalistic arguments either claim rights for the family or a traditional group as a collectivity or reject that claim.

4. Genealogical arguments claim coherence of the contextualist, or, respectively, the universalist agenda with human rights instruments.

5. Normative arguments comprise normative statements about equality.

In the traditionalist agenda, arguments that fall into Categories 1 and 2 demand special protection for the family or traditions by the state inasmuch as family or traditions have substantial or functional qualities deserving of such protection. The controversy regarding Category 1 unfolds over the question of definitions. Who or what is to be recognised as family or a traditional value? Battles over the definition of the family in human rights language are not new. Waites has pointed out that ever since the emergence of feminist movements from the 1960s, feminists have problematised key concepts used in the Declaration such as ‘marriage’ and ‘the family’. In light of contemporary feminist and queer theory, redefinitions emphasising the diversity of models of family or marriage as not involving only male–female partnerships are gaining ground.Footnote 48 The traditionalist agenda rejects gay marriage and consequently the idea that families of same sex parents and families of heterosexual parents should be considered equal.

Category 2 proves hardly controversial, since both sides tend to agree on the importance of families, and in part even of traditions. Category 3 makes an argument for protection of the family or traditional groups from the state: for example, the right of parents to be left alone by demands of public education. Arguments under Category 3 recall debates on collective rights. This is a controversial move and regularly rejected by egalitarian universalists, who disagree that families are collectives and that traditional groups and practices should be afforded special protections. Categories 4 and 5 develop arguments closely intertwined with the discursive strictures of human rights debate at the UN. Category 4 makes a genealogical argument, claiming coherence of the respective position with established human rights norms. Category 5 establishes the normative threshold of equality, which liberal actors defend in a strictly individualist and egalitarian key, specifying the demands of gender and generational equality. Contextualists also pay lip service to normative arguments. Mostly, however, they expand on substantial and functional arguments, which are the main drivers of their agenda.

When combined, these five categories make up more than 80 per cent of the debates between liberal actors and traditionalists in the text corpus for this article. What is interesting, however, is that the five categories are not distributed equally on the two sides. Normative, legalistic and genealogical arguments are more frequently used by liberal actors, who oppose the traditionalist agenda on principled grounds and try to maintain the interpretive sovereignty of human rights language and instruments. However, traditionalists also use genealogical and legalistic arguments. The use of such arguments requires an advanced degree of expertise in human rights treaty language and the history of debates. One finding from this research is that expertise on argumentation before the UN is being actively built up by traditionalist actors through the sharing of ideas, texts and background information.Footnote 49 For instance, the American conservative pro-family NGO United Families International, which has consultative status with the United Nations Economic and Social Council, publishes a regularly updated Pro-Family Negotiating Guide, also known as and hereinafter referred to as the ‘United Nations Negotiating Guide’, which systematically picks apart 70 years of UN treaties with the goal of identifying ‘pro-family’ positions and their opposition. Among the NGOs who use this guide, Concerned Women for America is quoted with the endorsement, ‘As this tool becomes widely available, it will be possible for people of good will to maintain the integrity of UN documents and to prevent their hijacking for ideological purposes.’Footnote 50 UN language often reads like a code. The United Nations Negotiating Guide used by pro-family actors gives a good insight into how traditionalists go about interpreting these codes. The Guide identifies which expressions support the traditionalist agenda (e.g., ‘the family is the basic unit of society’) and which terms threaten it (e.g., referring to the place of the child in the family, and the expression ‘the child’s right to confidentiality and privacy’)Footnote 51.

A selection of exemplary passages from the debates on traditional values and the family should make the five categories of argumentation more tangible: Resolution 21/3, entitled ‘Promoting human rights and fundamental freedoms through a better understanding of traditional values of humankind: best practices’, requested that the Advisory Committee of the UNHRC prepare a report. In response to this resolution, the Advisory Committee received 60 submissions between January and March 2013 from stakeholders (countries, NGOs and UN agencies) on the topic of traditional values. Resolution 29/22, entitled ‘Protection of the family: contribution of the family to the realisation of the right to an adequate standard of living for its members, particularly through its role in poverty eradication and achieving sustainable development’ was adopted on 3 July 2015. This resolution also requested the preparation of a report ‘on the impact of the implementation by States of their obligations under relevant provisions of international human rights law with regard to the protection of the family’. As a response to this resolution, the Office of the High Commissioner of Human Rights received, in the second half of 2015, 106Footnote 52 submissions from stakeholders (countries, UN bodies and NGOs). Combined, this text corpus gives a valid overview of the arguments used in the debate. The sections below look first at the liberal side and its rejection of the traditionalist agenda and then at the arguments used by the traditionalist side. Finally, we identify moments in the debate where stakeholders reflect on the debate as such and express a position that we call a communicative double bind.

Liberal critics of the traditionalist agenda

The Russian traditional values initiative between 2009 and 2013 tried to present itself as having a universalist agenda. The preliminary study on traditional values submitted to the Advisory Committee of the UNHRC by Russian rapporteur Vladimir Kartashkin repeated the argument advanced by the Russian Orthodox Church that human rights, duties, and responsibility to society are linked based on Article 29 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights:

Any society or State, the report states, has a system of ‘law – obligation – responsibility,’ without which the fundamental rights and freedoms of the individual cannot be guaranteed. This close link is underlined in [A]rticle 29 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.Footnote 53

The presentation of the traditionalist agenda in a universalist light was not well received by the Advisory Committee of the UNHRC, which substantially rewrote Kartashkin’s study and interpreted the traditionalist agenda strictly in contextualist terms, associating traditional values with debates on rights of indigenous people and not even mentioning Article 29.Footnote 54 Horsfjord concludes that, from the point of view of the traditionalists, ‘the traditional values study is the hegemonic international human rights discourse reasserting its power. It is the voice of ‘‘these fellows’’ who reflect ‘‘the opinion of a narrow circle of experts, functionaries, or noisy but well-organized minorities’’, to re-use Kirill’s own words’.Footnote 55 This assessment confirms the main argument of this article that the traditionalist agenda tries to present itself as truly ‘universal’, whereas the liberal viewpoint is presented by the traditionalist as elitist and sectarian.

The submissions by Western states and liberal NGOs directly responded to these attempts at redefining the terms of the debate. In response to the ‘Traditional values’ resolution, the EU submitted a statement that expressed in a paradigmatic way the standoff between universalist and contextualist positions, as seen from their standpoint:

Traditional values are inherently subjective and specific to a certain time and place. Human Rights are universal and inalienable. To introduce the concept of ‘traditional values’ into this discourse can result in a misleading interpretation of existing human rights norms, and undermine their universality.Footnote 56

This submission defined traditional values as ‘subjective and specific to a certain time and place’ against human rights that are ‘universal and inalienable’. The same type of argument was used by the United States in its detailed response to Resolution 29/22 on the family. The submission explained the decision to vote ‘no’ on an issue (the family) to which the country feels otherwise committed. It made a reference to the controversial debate inside the UNHRC wherein Russia blocked the amendment brought forward by Western countries to include the passage ‘in different cultural, political, and social systems, various forms of the family exist’ in the family resolution, and expressed its disagreement with the traditionalist agenda in substantial terms. The submission by the US rejected the use of legalistic arguments on collective rights by traditionalists: ‘The resolution’s focus on the family as a group unit, rather than focusing on the human rights of individuals within a family is troubling and inconsistent with international human rights law [added emphasis].’Footnote 57

The EU also reacted to the family resolution. It endorsed the functional aspect of the resolution (‘We […] recognize the valuable contributions that families make to strengthening our societies’ [added emphasis]), but expressed disagreement on legalistic, genealogical and normative grounds:

The family itself as a basic unit of the society is also to be protected. As endorsed by various UN fora, this protection should extend to all families, and all individuals within them, and should be fully reflective of established human rights standards in relation to human rights of women, gender equality, and the rights of the child [added emphasis].Footnote 58

Claims to rights for the family or a traditional group as a collectivity, or the rejection thereof, are a central arguments in the confrontation between liberal and traditionalist positions. Whereas the latter claim that a family is ‘more than the sum of its individuals’ and consequently should be treated as a unit entitled to special protection, liberals take an individualistic approach. They focus on the individual members of a family or group as right holders and reject the idea that the family should be protected by human rights instruments at all. A clear expression of this viewpoint comes from the submission of Amnesty International:

Amnesty International reiterates its concerns that Human Rights Council’s focus on ‘protection of the family’, including through Resolution 29/22 of 3 July 2015, is inconsistent with the Council’s mandate to promote and protect human rights. Human rights adhere to individual persons. The family, as a grouping, in and of itself is not a subject of human rights protection [added emphasis].Footnote 59

Among the EU Member States, only Denmark, Sweden, Hungary and the UK submitted additional individual positions on the family resolution. The UK submission expressed disagreement with the traditionalist agenda on substantive grounds (‘… there are more different types of family formations, including cohabiting partners, co-parents, … including opposite sex and same sex couples’) and endorsed functional arguments only with a qualifier: ‘strong and stable families and family relationships, in all their diverse forms, play an important role in our society [added emphasis]’.Footnote 60

Denmark and Sweden, which are classical social welfare democracies and have extensive state support programmes for families in place, gave an overview of these programmess and thereby made a constructive contribution to the debate along the lines of a functional argument. In the end, however, they debunked the entire resolution as inadmissible on genealogical and normative grounds and took issue with the definition of the family at play in the resolution:

Denmark finds that Resolution 29/22 does not reflect established human rights standards with regards to the human rights of girls and women, gender equality and the rights of the child nor does it properly recognise the fact that various forms of families exist [added emphasis].Footnote 61

Sweden’s view is that it [Resolution 29/22] does not adequately reflect the human rights of women, international commitments regarding gender equality and the rights of the child [added emphasis].Footnote 62

Hungary’s submission is noteworthy because it carefully avoids giving a negative assessment of Resolution 29/22 on normative grounds. In fact, the normative category in the Hungarian statement resembles the use of this category by traditionalists when they pay lip service to gender equality: ‘Hungary thereby construes its family policy in accordance with gender policies, the two being indistinctly interrelated [added emphasis].’Footnote 63

From these statements, one gathers that the opposition to the traditionalist agenda from Western liberal democratic states hinges on disagreement over substantive and normative definitions and over the correct interpretation of human rights norms. On functional terms, both liberal Western countries and traditionalist actors are in principle in agreement that families play an important role in society and should receive support from the state. As a matter of fact, all individual country submissions, especially from Western Europe, go into great detail outlining the family policies implemented by their countries. Western countries sought to avoid being earmarked as ‘anti-family’ countries by pointing to large sums of public money that go into policies that support women, children and a wide range of household arrangements variously defined by them as falling under the category of ‘family’.

Supporters of the traditionalist agenda

Despite the inclusion of functional arguments in statements by liberal actors, NGO submissions favourable to Resolution 29/22 still argued that, on the question of the family, functional arguments on the social worth of the family were not a priority for Western countries. A joint statement by a group of Catholic NGOs stated that ‘the co-signers find it most regrettable that many States and some United Nations agencies portray this key social institution [the family] more as a ‘‘problem’’ than as a resource’.Footnote 64 This line of argumentation is echoed and spelled out in greater clarity by this submission from a Catholic NGO:

Regrettably, such a resolution on protection of the family, that was meant to mark the 20th anniversary of the International Year of the Family and to offer a useful opportunity to draw further attention on increasing cooperation at all levels on family issues and on undertaking concerted actions to strengthen family centered policies and programs [Category 2], did not find consensus among all the Member States … we regret the fact that many States and some United Nations agencies portray the family more as a ‘problem’ than as a resource. Notwithstanding the fact that human rights of individuals must be always protected within the family, to focus only on the rights of family members as advocated by some States means to deny that the family is much more than the sum of its individuals [emphasis added].Footnote 65

One of our interviewees made a similar argument during our conversation. In this respondent’s opinion, the engagement of Russia was:

breaking up the non-willingness of European countries and the US to engage into defending that sort of values … You had in all the previous years, the last ten years, the non-willingness from almost all European countries, except perhaps from Italy and only on some issues Hungary, Poland – yes, these are probably the exceptions – to promote or to really advance that sort of agenda. That, this is, this is the novelty.Footnote 66

Several submissions demonstrate that stakeholders perceive the opposition between liberal and traditionalist standpoints as a deeply entrenched conflict. This entrenchment is expressed with genealogical arguments, each side claiming to have the history of human rights as established by the UN on their side. Traditionalists depict their struggle as the fight of a traditionalist majority against a small but powerful group of liberal progressivists that has the UN bureaucracy on its side. Caritas Internationalis, for example, describes the opposition as one between ‘the hearts of the world’s people’ and ‘many forces in today’s society’:

The family comes first in the hearts of the world’s people and continually exhibits much greater vigor than the many forces in today’s society that try to threaten or even eliminate it. The co-signing organizations stand firm in their support of such vigor, and plan to constantly advocate for better protection and support of the family and all its members as the fundamental unit of society [added emphasis]Footnote 67.

It is noteworthy that this statement tries to chart a middle ground between traditionalists and liberals, mentioning both the family as a unit and the individual members of the family. Another Christian NGO, The Center for Family & Human Rights (C-Fam), portrays the situation as a conflict between ‘few developed countries’ and ‘all UN member states’ when it states that:

Only a few developed countries have changed their laws to recognize a special status for homosexual relationships, yet they argue this requires a change to the universal, longstanding understanding of family for all UN member states and UN policy.Footnote 68

Again, we see here that the individualist egalitarian approach to human rights, which has habitually been associated with the Western liberal position on human rights, is depicted as elitist and sectarian (‘few developed countries’) and the traditionalist position, which stands in the lineage of contextualist arguments, is presented as truly universal (‘all UN member states’). Several submissions also attack UN agencies for promoting the liberal agenda instead of being neutral or representative of the breadth of positions inside the UN. The Alliance of Romania’s Families accuses ‘the United Nations and some of its agencies and treaty bodies’ of ‘a doctrinal and practical approach which diminishes and even destroys the legitimate ends of marriage and family and their role in society’.Footnote 69 Another submission calls the UN Officer of Human Rights, who was responsible for the report, deceitful (‘duplicitous’). The report, it says, ‘attempts, duplicitously, to expand the meaning of family to include concepts which have never been accepted by UN member states in any binding treaty’.Footnote 70 In this way, the traditionalist agenda turns around the liberal egalitarianism of its opponents into a restrictive, elitist, and anti-pluralistic position.

The resolutions on ‘Traditional values’ and ‘Protection of the family’ made apparent a split between the positions of Western European countries and stakeholders, which the EU, with its statement on behalf of all, could not really gloss over. Hungary’s submission was more in support of the traditional position than that of the EU, and a great number of NGOs from EU countries also supported the traditionalist agenda. Traditionalist actors take this fact as a further argument in support of their claim that liberal universalism is actually partial and hegemonic, and don’t shy away from comparing the Brussels of today with the Moscow of the Soviet Union. The diplomat from Belarus compared the situation of the EU with the Soviet Union: ‘The Belorussian Soviet Socialist Republic, the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic, the Russian Federation, and the delegation of the Soviet Union always coordinated their policy positions … what I have observed of how the EU operates is basically the same.’Footnote 71

VI. The liberal–traditionalist double bind

So far, this article has tried to show that the traditionalist agenda blurs and redraws the conceptual boundaries between the universalist and contextualist positions in the human rights discourse. The traditionalist agenda calls into question the habitual distinction between the universalist position as liberal, egalitarian and progressive, and the contextualist position as illiberal, restrictive and relativist. Instead, the traditionalist agenda under scrutiny in this article presents itself as conservative, but as equally ‘universal’ as the liberal position promoted by Western states or, indeed, the UN bureaucracy itself.

However, there is one more aspect that should be brought out in this analysis. Not only have the ‘Traditional values’ and ‘Protection of the families’ resolutions put Western states on the defensive, they have also put many traditionalist civil society organisations from Western countries into the awkward position of siding with a coalition of illiberal actors from Russia, Islamic States and the Global South. The traditionalist agenda polarises and effectively blocks a broader debate about the sources and evolution of human rights, reducing it to a ‘zero-sum clash of cultures and values’.Footnote 72 This is a problem for a number of actors, who find the traditionalist agenda important and in part persuasive, but do not agree with its strategy nor want to side unconditionally with the states that promote it.

One interviewee from the NGO sector explained to us that the organisation this person worked for supported the traditionalist agenda promoted by Russia since 2012, but preferred not to appear too closely associated. They would, for example, avoid availing themselves of the co-sponsorship from the Russian or the Belorussian delegation directly when organising an event, preferring instead the co-sponsorship of less conspicuous countries like Samoa or Vietnam.Footnote 73 Interviewee C from the NGO sector remarked that in his view, Vatican diplomacy was cautious not to be associated too closely with the Russian agenda:

The Holy See has wanted to play always in the sense that it won’t be only Russia, but a couple of other countries too, especially to support [a] resolution, so that it doesn’t appear that the Holy See is [unintelligible] to the interest of Russia.Footnote 74

The view was corroborated by one further interviewee from a UN diplomatic delegation, who said while they actually supported the goals of the resolutions on ‘Protection of the family’, they did not support the ‘unhelpful and intense, prescriptive language’ in which the debate had been couched.Footnote 75 This interviewee admitted to finding the work of a lot of conservative NGOs who intervened in support of the ‘Protection of the family’ resolution ‘unhelpful’ and specified: ‘I want everything they want, but I disagree a hundred per cent about their strategy.’Footnote 76

These actors, we argue in this final section, find themselves in a communicative deadlock, better described as communicative double bind. A double bind is a communicative situation in which an individual is confronted with two conflicting demands, neither of which can be ignored or escaped. A subject in a double-bind situation is torn both ways, so that whichever demand he or she tries to meet, the other demand cannot be met. Developed in the context of clinical psychology,Footnote 77 the constellation of the double bind can also be applied to political communication.Footnote 78 The communicative double bind describes well the situation of a particular group of actors in the context of debates inside the UNHRC over items on the traditionalist agenda, namely the position of moderate conservative stakeholders. These are, as expressed in the statements above, often religious NGOs supportive of the goals of the traditionalist agenda, but unwilling to be associated with the illiberal and anti-democratic credentials of the leaders of the discussion. The existence of a communicative deadlock was confirmed by Bielefeldt during our interview, when he said:

The opposition created by the launching of the traditional values agenda is destructive. These resolutions create a situation in which you are told ‘either you buy traditionless freedom and a completely contextless, abstract freedom, or you buy tradition’ and then you are per se in an anti-liberal context. This is appalling. Neither does it do justice to the real question, nor is it good for the discourse constellation. But they [the traditionalists] have launched this divisive strategy very cleverly and I believe there is a lot of confusion.Footnote 79

But not only some NGOs, also Western states find themselves confronted with two conflicting demands, both of which are considered legitimate and important, but cannot be met simultaneously. Being liberal actors, Western states defend an individualistic and egalitarian application of human rights and oppose any attempt to restrict human rights on grounds of tradition or culture. At the same time, being the wealthiest nations on the planet and – in most cases – implementers of social welfare, the Western states represent political systems that are generally supportive of the practical goals advocated by the traditionalist agenda (for example, in the field of family policies). The double bind for them lies in the discrepancy between the merit of the question and the strictures of the communicative situation in which it is posed: Western liberal states in the UNHRC vote against the promotion of traditional values and the protection of the family. They are subsequently branded by supporters of the traditionalist agenda as enemies of tradition and the family, despite the fact that in practical terms, Western governments frequently provide more support for the causes raised by the traditionalist agenda than those countries that claim to promote it.

A good example for this discrepancy between rhetoric and actual commitment was the intersessional seminar on the protection of the family and disability organised in Geneva on 23 February 2017 by the Group of the Friends of the Family. Under the title ‘The impact of the implementation by States of their obligations under relevant provisions of international human rights law with regard to the protection of the family on the role of the family in supporting the protection and promotion of the rights of persons with disabilities’, members of the group convened a seminar with the aim to discuss ‘the family as the fundamental unit of society’ and ‘recognize the important roles played by families in caring for and supporting persons with disabilities’.Footnote 80 The event was accompanied by a photo exhibition on family at the UN Office in Geneva, organised by the Belarusian delegation.Footnote 81 Russia and Belarus are two countries with a harrowing record when it comes to giving care and support to persons with disabilities and their families. It is therefore nothing short of paradoxical that these countries present themselves as leaders on the topic of family and disability, whereas research clearly shows that it has been the influence from Western European countries, in particular Western NGOs that is slowly helping to improve the situation for persons with disabilities in the region of the former Soviet block.Footnote 82

The traditionalist agenda inside the UN has created a communicative situation in which Western liberal states and moderate conservative actors stand to lose. Most of the stakeholders seem to be aware of this. The following statement by Caritas Internationalis echoes the sense of irritation experienced by Western religious NGOs, who see their countries in opposition on a topic they support. The statement identifies a communicative deadlock over definitions at the heart of the conflict:

In order to have a constructive dialogue at the United Nations, we should leave behind the arguments on the definition of the family that may be divisive according to different cultural, ideological, religious interpretations and maintain the universal agreed language of human rights law that unanimously reaffirms the key role played by the family in the society [added emphasis].Footnote 83

The actors which we interviewed for this article also lamented the polarisation of the debate. Asked whether the resolutions on ‘Protection of the family’ had led into a communicative deadlock, Bielefeldt confirmed and suggested that only a new type of conversation may solve the impasse:

In order to counter this mechanism, one would need, to some extent, a thorough consideration of principles (‘Grundsatzreflexion’), and the conditions in Geneva are not conducive to that. If you know how debates take place there, with these extremely short speaking slots, always pro or contra …This is not something you can answer with pro and contra, but with a principled reflection on the question and the categories that are being used.Footnote 84

The argument made here is that in order to overcome the situation of the double bind, a real dialogue between the stakeholders would be necessary, but that the institutional speech situation hardly allows for this. This argument came up more than once in our research, with another interviewee telling us:

It’s not a dialogue, for Heaven’s sake, you have one minute and thirty seconds, one minute and forty-five seconds, if all things go well, and privileged states will have two minutes and fifty seconds to speak. And you will have four hours of so-called dialogue, which is no dialogue at all, but a superposition of monologues, where everybody speaks at top speed to get one page and a half read during that one minute and thirty seconds. And the NGOs, if you still have time at the end of the so-called dialogue, will have between forty-five seconds and thirty seconds to speak. So this not dialogue for Heaven’s sake. This is, this is formal, formal democracy stretched to absurdity, where the real, the real decision is taken through power plays that are decided before the reunion between groups of states.Footnote 85

In this speech situation, the traditionalist agenda provokes ‘reflexes of purification’ on both sides, according to Bielefeldt, furthering the ‘clash of cultures and values’ also observed by McCrudden.

VII. Conclusion

The opposition between universalist and contextualist positions inside the human rights universe is not a novelty. However, as this article shows, the traditionalist agenda spearheaded by Russia since 2009 has pulled non-liberal views on human rights out of the contextualist and culturalist corner into a ‘universalism’ of its own making, directly in contrast with the individualistic egalitarian universalism of the liberal view on human rights. Russia’s role as antagoniser in human rights law is not limited to the UNHRC, but is part of the bigger picture of Russia’s place in the international legal system: the European Court of Human Rights, the Council of Europe, or the OSCE are alternative fora where Russia acts as polariser over the meaning of human rights.Footnote 86

In the UNHRC, the new transversal message promoted by the traditionalist agenda has gathered majority support and has put Western countries in a minority position. The topics of ‘Traditional values’ and ‘Protection of the family’ have polarised debates in the UNHRC in a way that has put a specific group of actors into a situation of an argumentative double bind. Some religious NGOs from Western countries overlap with the traditionalist agenda on functional grounds, but disagree on strategy and political implications. Moderate conservative actors express puzzlement to find themselves on one side with Russia, against liberal democratic governments they otherwise support.

Some of the stakeholders on the liberal and conservative side who appear wary about the double bind argue that a way out could lie in a new culture of institutional debate inside the UNHRC. This new culture of debate would have to start, according to Bielefeldt, from ‘a critical hermeneutic of tradition’, because all rights ‘are always also relational rights’.Footnote 87 Also McCrudden, who takes a moderately positive stance on traditional values, argues that human rights should strive to reconcile tradition and faith with freedom and equality.Footnote 88 These actors appeal to a school of thought in political theory that seeks to reconcile universalism and cultural relativism and to chart a deliberative middle ground of reflective equilibrium between contrasting visions.Footnote 89 Such a proposal will not convince those actors on the liberal and on the traditionalist side who believe that the best way to overcome a double bind is to have one side win the struggle. The political motivation behind the traditionalist agenda promoted by Russia since 2009 appears to be polarisation, not advancement on topics of common concern, and for this reason it is likely that tensions over human rights will increase.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Franz Eder (University of Innsbruck) for his advice on data visualisation and Anna Shirokanova (National Research University Higher School of Economics) for her advice on data visualisation and R software. We furthermore thank Julia Mourão Permoser (University of Innsbruck), Martin Senn (University of Innsbruck) and Anja Hennig (Viadrina University Frankfurt/Oder) for helpful comments on earlier versions of this draft. We also thank two anonymous peer reviewers and the editors of Global Constitutionalism for their comments. This article was written with the support from the European Research Council (ERC STG 2015 676804).

Appendix 1

The set of 69 texts on the Traditional values resolutions:

1. Resolution 12/21: Promoting human rights and fundamental freedom through a better understanding of traditional values of humankind. A/HRC/RES/12/21 (2009)

2. Workshop on traditional values of humankind. A/HRC/16/37 (2010)

3. Resolution 16/3: Promoting human rights and fundamental freedoms through a better understanding of traditional values of humankind. A/HRC/RES/16/3 (2011)

4. Resolution 21/3: Promoting human rights and fundamental freedoms through a better understanding of traditional values of humankind: best practices. A/HRC/RES/21/3 (2012)

5. Preliminary study on promoting human rights and fundamental freedoms through a better understanding of traditional values of humankind. A/HRC/AC/8/4 (2012)

6. Study of the Human Rights Council Advisory Committee on promoting human rights and fundamental freedoms through a better understanding of traditional values of humankind. A/HRC/RES/22/71 (2012)

7. Summary Information from States Members of the United Nations and Other Relevant Stakeholders on Best Practices in the Application of Traditional Values while Promoting and Protecting Human Rights and Upholding Human Dignity. A/HRC/24/22 (2013)

Submissions as received by the OHCHR:

In May 2010:

8. Marangopoulos Foundation for Human Rights

In May 2011:

9. Marangopoulos Foundation for Human Rights

In January–March 2013 after Res 21/3: Promoting human rights and fundamental freedoms through a better understanding of traditional values of humankind: best practices. A/HRC/RES/21/3:

Groups of States or regional groups

10. EU

Member States

11. Belarus

12. Bosnia and Herzegovina

13. Guatemala

14. Honduras

15. Indonesia

16. Iraq

17. Mauritius

18. Oman

19. Qatar

20. Serbia

21. Spain

22. Sri Lanka

23. Syrian Arab Republic

24. Uzbekistan

UN Department and Agencies

25. UNRWA (United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East)

Other Stakeholders

26. Acción Solidaria

27. AFAN (Asociación De Familias Numerosas De Guatemala), Guatemala

28. Alliance Defending Freedom (aka Alliance Defense Fund, an ECOSOC-accredited non-governmental organization)

29. Alliance of Romania’s Families (Alianța Familiilor din România), Peter Costea, President

30. Amando la Vida (Fundación Amando La Vida)

31. Amnesty International

32. ARC International

33. ASOVID (Asociación Vida y Dignidad Humana, Filial de Vida Humana Internacional, y de Human Life International)

34. Association Points-Coeur

35. Association Relwende pour le Development

36. Catholics for Choice

37. Catholic Family and Human Rights Institute

38. Congregation of Our Lady of Charity of the Good Shepherd, Hedwig Jöhl and Marioly Céspedes Zardán, Bolivia

39. Defensoria del Pueblo de Colombia

40. Familia Importa (Mirna de González)

41. Fundación Contemporánea

42. Fundación Sí a La Vida de El Salvador

43. Global Helping to Advance Women and Children (HAWC)

44. Instituto Uruguayo de Formación Familiar (IUFF), Ana María Abel. Montevideo, Uruguay

45. International Service for Human Rights (ISHR)

46. Joint submission I (Asociación Codedena, FADEP, Jovenes en Red, Fundación Alive, Asociacion Sí a La Vida, Asociación ASOVID, Fundación ENLACE, Asociación de Abogadas Por La Vida, Asociación Familia Importa, Jóvenes Pro-Life Guatemala, Asociación Por Una Publicidad Digna, JUVID)

47. Joint submission III (Amnesty International, Association for Women’s Rights in Development (AWID), Centre for Women’s Global Leadership (CWGL), International Service for Human Rights (ISHR), Nazra for Feminist Studies and World Organization Against Torture (OMCT))

48. Kenya Legal & Ethical Issues Network on HIV and AIDS (KELIN)

49. Mary Langlois

50. Centre interdisciplinaire pour les droits culturels (CIDC) de l’Université de Nouakchott

51. Meilleurs pratiques de Rwanda

52. Movimiento Familiar Cristiano en Panamá

53. National Centre for Human Rights Uzbekistan

54. Natural Justice, Cape Town

55. Nazra for Feminist Studies

56. People’s Welfare & Development Society, Trilok Chandra Srivastava. Jodhpur [Rajasthan], India

57. Public Defender of Georgia, (PDO), Ucha Nanuashvili, Nino Tsagareishvili

58. Felix A. Quintero-Vollmer

59. Rights Watch (Human Rights Watch), Christopher Stanley, UK

60. Russian LGBT Network

61. Janice Shaw Crouse, Ph.D.

62. SRI (Sexual Rights Initiative)

63. Tetoka Voluntades que Trascienden

64. Ukrainian Parliament Commissioner for Human Rights

65. Universidad Católica Santo Toribio de Mogrovejo, Chiclayo, Peru (Instituto de Ciencias para el Matrimonio y la Familia, Facultad de Derecho – Universidad Católica Santo Toribio de Mogrovejo)

66. VIFAC (Vida y Familia Chihuahua), Ing. Beatriz E. Amaya Estrada

67. Voto Católico Colombia (Voto Católico), Jesús Arturo Herrera Salazar. Bogota, Colombia

68. Voz Pública A.C. (Voz Pública A.C.)

69. Women for Development, Republic of Chechnya

The set of 127 texts on the Protection of family resolutions:

1. Resolution 26/11: Protection of the family. A/HRC/RES/26/11

2. Summary of the panel discussion on the protection of the family. A/HRC/28/40.

3. Resolution 29/22: Protection of the family: contribution of the family to the realization of the right to an adequate standard of living for its members, particularly through its role in poverty eradication and achieving sustainable development. A/HRC/RES/29/22.

4. Resolution 32/23: Protection of the family: role of the family in supporting the protection and promotion of human rights of persons with disabilities. A/HRC/RES/32/23

5. Joint Letter of Special Procedures mandate holder to the President of the Human Rights Council (3 July 2015)

6. Statement by the Chairperson of the Coordination Committee of Special Procedures (A/HRC/28/41, Annex X)

7. Letter of the President of the Working Group on the issue of discrimination against women in law and in practice (1 September 2015)

8. Note Verbale to All Permanent Missions to the United Nations in Geneva (HRC Res 29/22)

9. Advance Unedited Version of the report on protection of the family: contribution of the family to the realization of the right to an adequate standard of living for its members, particularly through its role in poverty eradication and achieving sustainable development. A/HRC/31/37.

10. Protection of the family: contribution of the family to the realization of the right to an adequate standard of living for its members, particularly through its role in poverty eradication and achieving sustainable development. Report of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. A/HRC/31/37.

Submissions as received by OHCHR:

In October–November 2015 for the Report of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights A/HRC/31/37. Protection of the family: contribution of the family to the realization of the right to an adequate standard of living for its members, particularly through its role in poverty eradication and achieving sustainable development.

Submissions by Member States

11. Argentina

12. Azerbaijan

13. Bahrain

14. Belarus

15. Bosnia and Herzegovina

16. Chile

17. Colombia

18. Denmark

19. Egypt

20. Hungary

21. Iran

22. Kuwait

23. Mexico

24. Qatar

25. Oman

26. Peru

27. Russian Federation

28. Saudi Arabia

29. Sweden

30. Trinidad and Tobago

31. Tunisia

32. United Arab Emirates

33. United Kingdom

34. United States of America

35. Zimbabwe

Submissions by national human rights institutions

36. Albania – Ombudsman Institution

37. Cape Verde – Comissão Nacional para os Direitos Humanos e Cidadania

38. Mexico – Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos

Submissions by UN bodies and international organisations

39. United Nations Population Fund

Submissions by other entities

40. European Union

Submissions by civil society organisations

41. ABA-ABIA-ABEP-Cfemea-CLAM/UERJ-IPAS/Brazil-SPW (Joint submission: ABA – Associação Brasileira de Antropologia, ABIA – Associação Brasileira Interdisciplinar de AIDS, ABEP – Associação Brasileira de Estudos, Cfemea – Centro Brasileiro de Estudos e Assessoria, CLAM/UERJ – Centro Latino-Americano em Sexualidade e Direitos Humanos, IPAS/Brazil – Ações Afirmativas em Direitos e Saúde, SPW – Sexuality Policy Watch)

42. ADF International

43. Alliance of Romania’s Families

44. Allied Rainbow Communities

45. Amar Es – Alianza Cívica Juvenil (Joint submission)

46. Amnesty International

47. Asia Pacific Alliance for Sexual and Reproductive Health Rights

48. Asian Pacific Research and Resource Center for Women (ARROW) (Joint: Asian Pacific Resource and Research Centre for Women (ARROW), Malaysia; Likhaan Center for Women’s Health, Philippines; Moroccan Family Planning Association (MFPA), Morocco; Naripokkho, Bangladesh; Rural Women’s Social Education Centre (RUWSEC), India; Shirkat Gah, Pakistan; Sisters In Islam, Malaysia; Society for Health Education, Maldives; Women and Media Collective, Sri Lanka; Yayasan Kesehatan Perempuan (YKP) – Women Health Organization, Indonesia)

49. Asociación de Familias Numerosas de Madrid

50. Asociación La Familia Importa (AFI)

51. Asociación Stella Maris

52. Association for Women Rights in Development

53. Associazione Comunità Papa Giovanni XXIII

54. Center for Economic and Social Rights (CESR)

55. Center for Family and Human Rights (C-Fam)

56. Center for Reproductive Rights

57. Centro de Estudios y Formación Integral para la Mujer (CEFIM)

58. Centro de Investigación Social Avanzada (CISAV)

59. Child Rights International Network (CRIN)

60. CitizenGo – La célula básica de la sociedad

61. Comunidad y Justicia

62. Confederation of Family Associations in the Carpathian Basin (KCSSZ)

63. Construye – FORLID – RedMex – Pasosx laVida (Construye Observatorio Regional para la Mujer de América Latina y el Caribe A.C., Pasos por la Vida A.C., FORLID Formación de Líderes Universitarios con Valor, Red Mx Política Universitaria para el Bien Común)

64. Enraizados

65. Familia y Sociedad

66. Fédération des Associations Familiales Catoliques en Europe (FAFCE)

67. Femina Europa

68. Foro de Diálogo Civil de Paraguay

69. Friends World Committee for Consultation – Quakers

70. Fundación Familia y Futuro

71. Fundación Sí a La Vida

72. Global HAWC – UN Family Rights Caucus (Joint submission)

73. Global Initiative for Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights

74. Health Education Rights Alternative HERA XXI

75. Howard Center for Family, Religion, and Society

76. Institute for Family Policy (IFP)

77. Instituto Panameño de Educación Familiar

78. Intermedia Social Innovation

79. International Center for Family Studies (CISF)

80. International Lesbian and Gay Association

81. International Muslim Women Union

82. Investigación, Formación y Estudios de la Mujer (ISFEM)

83. IPPF – RFSU – SoP – SoS_Rutgers (Joint submission: The International Planned Parenthood Association – IPPF, the Swedish Association for Sexuality Education – RFSU [Sweden], Sex og Politik [Norway], Sex og Samfund [Denmark] and Rutgers [The Netherlands])

84. ISHRI – SCSS (Joint submission, International Solidarity and Human Rights Institute and the Society of Catholic Social Scientists)

85. Jamaica Coalition for a Healthy Society

86. Kvinna till Kvinna Foundation

87. Magdalene Institute

88. Musawah

89. Network of European LGTB Families Association (NELFA)

90. Ordo Iuris

91. Orientación Para la Joven (OPJ)

92. Out Right Action International

93. Parents Rights in Education (PED)

94. Partners for Law in Development (PLD)

95. Point-Coeurs

96. Population Research Institute (PRI)

97. Profesionales por la Ética

98. Rainbow Community Kampuchea (RoCK)

99. Red por la vida

100. Red pro Yucatán

101. Ridge Project

102. Save the Children (Joint Submission: Child Rights Connect [formerly Groupe des ONG pour la Convention relative aux droits de l’enfant], Defence for Children International [DCI], Plan International, Save the Children, World Vision International)

103. Sexo Seguro

104. Sexual Rights Initiative

105. Spanish Family Forum

106. Unidos por la vida Colombia

107. Unión Mundial de Organizaciones Femeninas Católicas (UMOFC)

108. United Families International

109. Vida SV

110. Voz Publica AC (VOPAC)

111. Women in Development Europe (WIDE+)

112. Women of the World Platform

113. Yo Influyo

In 2014 after the Resolution 26/11: Protection of the family. A/HRC/RES/26/11

114. Global Helping to Advance Women and Children

115. International Alliance of Women

116. Joint written statement submitted by Save the Children International, World Vision International, non-governmental organizations in general consultative status, Groupe des ONG pour la Convention relative aux droits de l’enfant, Defence for Children International, Geneva Infant Feeding Association, International Federation of Social Workers, International Social Service, Plan International, Inc., SOS Kinderdorf International, Terre Des Hommes Federation Internationale, non-governmental organizations in special consultative status

117. Alliance Defense Fund

118. International Institute for Peace, Justice and Human Rights (IIPJHR)

119. Joint written statement submitted by Caritas Internationalis (International Confederation of Catholic Charities), New Humanity, non-governmental organizations in general consultative status, Associazione Comunita Papa Giovanni XXIII, Edmund Rice International Limited, International Association of Charities, International Catholic Child Bureau, Pax Romana (International Catholic Movement for Intellectual and Cultural Affairs and International Movement of Catholic Students)

120. International Humanist and Ethical Union

121. Howard Center for Family, Religion and Society

122. Catholic Family and Human Rights Institute

In February 2015 as reaction to the Panel discussion on the protection of the family and its members:

123. Associazione Comunita Papa Giovanni XXIII

In February 2016 as reaction to the Report of the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights entitled ‘Protection of the family: contribution of the family to an adequate standard of living for its members, particularly through its role in poverty eradication and achieving sustainable development’: