No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

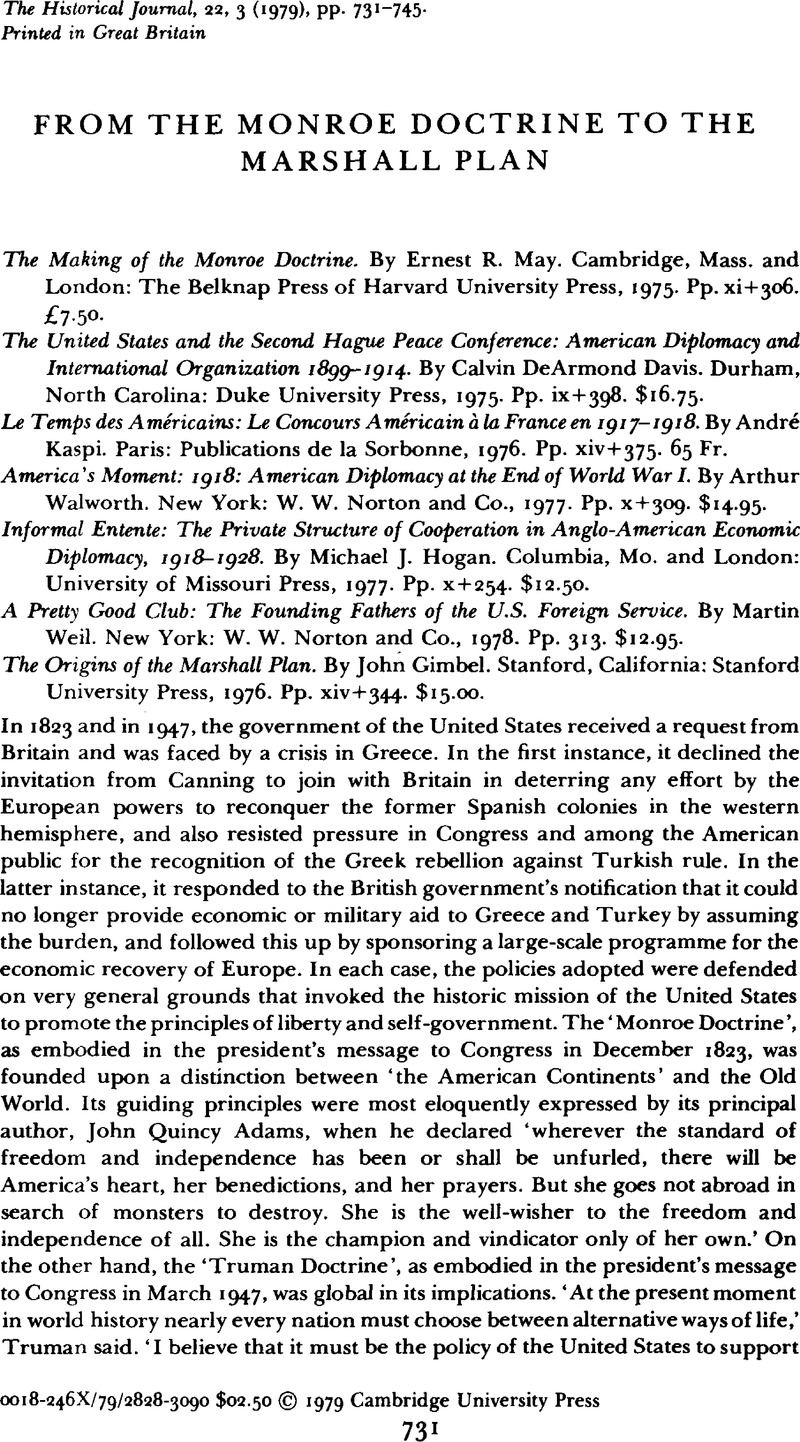

From the Monroe Doctrine to the Marshall Plan

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Articles

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 1979

References

1 For substantial reviews of this historiography, see Charles E. Neu, ‘The changing interpretive structure of American foreign policy’, and, more especially, Trask, David F., ‘Writings on American foreign relations: 1957 to the present’ in Braeman, John, Bremner, Robert H. and Brody, David (eds.). Twentieth-century American foreign policy (Ohio State University Press, 1971), pp. 1–57. 58–118Google Scholar.

2 For example, Allison, Graham T., Essence of decision: explaining the Cuban missile crisis (Boston, 1971)Google Scholar and Gallucci, Robert L., Neither peace nor honor: the politics of American military policy in Viet-Nam (Baltimore and London, 1975)Google Scholar.

3 Gaddis, John Lewis, The United States and the origins of the cold war, 1941–1947 (New York and London, 1972), p. 360Google Scholar.

4 Davis, Calvin DeArmond, The United States and the first Hague peace conference (Ithaca, N.Y., 1962), especially pp. 110–24Google Scholar.

5 Ibid. pp. 175–80.

6 See Osgood, Robert Endicott, Ideals and self-interest in America's foreign relations: the great transformation of the twentieth century (Chicago, 1953), pp. 86–8, 94Google Scholar.

7 ‘For declaration of war against Germany: address delivered at a joint session of the two Houses of Congress, April 2, 1917’, Baker, Ray Stannard and Dodd, William E. (eds.), The public papers of Woodrow Wilson: war and peace (New York, 1927), I, 16Google Scholar.

8 Notably, Mayer, Arno J., Political origins of the new diplomacy, 1917–1918 (New Haven, 1959)Google Scholar and Politics and diplomacy of peacemaking: containment and counterrevolution at Versailles, 1918–1919 (New York, 1967), and Levin, N. Gordon Jr, Woodrow Wilson and world politics: America's response to war and revolution (New York, 1968)Google Scholar.

9 Cf. Mayer, Politics and diplomacy of peacemaking.

10 E.g. Parrini, Carl P., Heir to empire: United States economic diplomacy, 1916–1923 (Pittsburgh, 1969), pp. 1–2, 19–22Google Scholar; Jones, Gareth Stedman, ‘The history of U.S. imperialism’ in Blackburn, Robin (ed.), Ideology in social science: readings in critical social theory (London, 1972), pp. 230–4Google Scholar.

11 ‘The legend of isolationism in the 1920s’, Science and Society, XVIII (1954), 1–20.

12 Williams, William Appleman, The tragedy of American diplomacy, 2nd revised and enlarged edition (New York, 1972), pp. 108–13Google Scholar.

13 Ibid. pp. 127–61. Quotes at p. 129.

14 The most important of the published work is Parrini, Heir to empire; Wilson, Joan Hoff, American business and foreign policy (Lexington, Ky, 1971)Google Scholar; Costigliola, Frank C., ‘The other side of isolationism: the establishment of the first World Bank, 1929–1930’, Journal of American History, LIX (1972), 602–20Google Scholar and ‘Anglo-American financial rivalry in the 1920s’, Journal of Economic History, xxxvii (1977), 911–34Google Scholar; Leffler, Melvyn P., ‘Political isolationism, economic expansion, or diplomatic realism: American policy toward western Europe, 1921–1933’, Perspectives in American history, viii (1974), 413–61Google Scholar; and, for a slightly earlier period, Kaufman, Burton I., Efficiency and expansion: foreign trade organization in the Wilson administration, 1913–1921 (Westport, Conn., and London, 1974)Google Scholar.

15 Wiebe, Robert H., The search for order, 1877–1920 (New York, 1967)Google Scholar; Galambos, Louis, ‘The emerging organizational synthesis in modern American history’, Business History Review, XLV (1970), 279–90CrossRefGoogle Scholar; Hawley, Ellis W., ‘Herbert Hoover, the commerce secretariat and the vision of an “associative state”, 1921–1928’, Journal of American History, LXI (1974), 116–40CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

16 He refers specifically to Parrini, Heir to empire and Costigliola, Frank C., ‘The politics of financial stabilization: American reconstruction policy in Europe, 1924–1930’ (Ph.D. dissertation, Cornell University, 1972)Google Scholar.

17 For a fuller, critical analysis of this interpretation, see Thompson, J. A., ‘William Appleman Williams and the “American Empire”’, Journal of American Studies, vii (1973), 91–104CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

18 Perkins, Dexter, ‘The department of state and American public opinion’ in Craig, Gordon A. and Gilbert, Felix (eds.), The diplomats, 1919–1939 (Princeton, 1953), pp 282–308Google Scholar.

19 May, Ernest R., ‘Lessons’ of the past: the use and misuse of history in American foreign policy (New York, 1973), pp. 19–51Google Scholar, especially pp. 23–38. This point has also been incorporated by Yergin, Daniel into his recent synthesis, Shattered peace: the origins of the cold war and the national security state (London, 1978). See especially pp. 18–21, 26–41, 87–92, 152, 188–9, 243–4, 262–4, 309Google Scholar.

20 The earlier books are A German community under American occupation: Marburg, 1945–52 (Stanford, Cal., 1961) and The American occupation of Germany: politics and the military, 1945–1949 (Stanford, Cal., 1968).

21 For a fuller exposition of this point of view, see Jones, Joseph Marion, The fifteen weeks (February 21-June 5, 1947) (New York, 1955)Google Scholar.

22 Kennan, George F., Memoirs 1925–1950 (Boston, 1967), p. 323Google Scholar.