No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

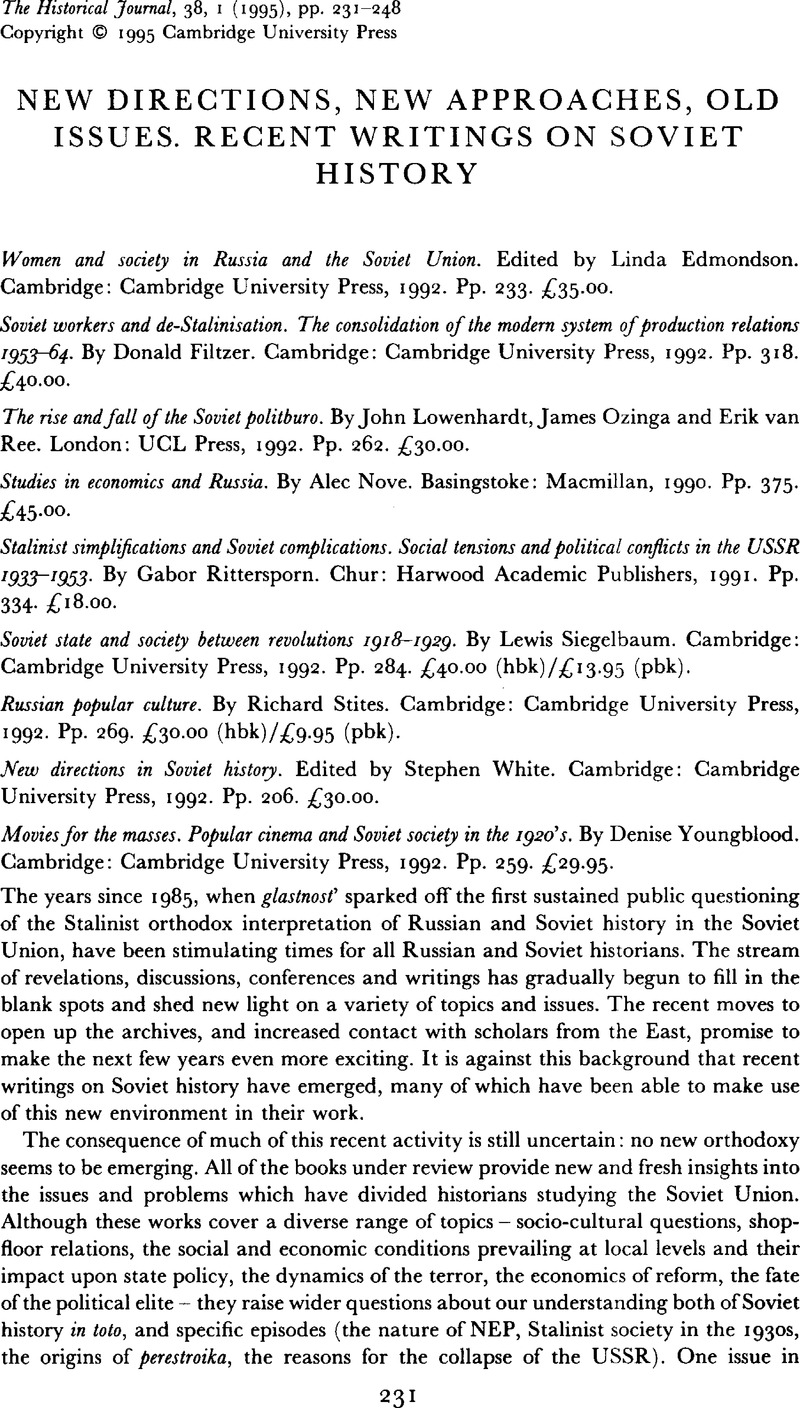

New directions, new approaches, old issues. recent writings on Soviet History

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 11 February 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Articles

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Cambridge University Press 1995

References

1 For a sustained, and at times heated, discussion of these issues, see the articles, ‘New perspectives on Stalinism’, Russian Review, XLV 4 (1986)Google Scholar and XLVI 4 (1987).

2 Ibid. See especially the articles by G. Eley and P. Kenez in XLV (1986).

3 White, S., New directions in Soviet history (Cambridge, 1992), p. xiv.Google Scholar

4 Ibid. pp. 33–4.

5 Ibid. pp. 75–6.

6 Ibid. p. 62.

7 Ibid. p. 41.

8 Youngblood, D., Movies for the masses (Cambridge, 1992), p. 9.Google Scholar

9 Ibid. pp. 28–9.

10 Ibid. p. 48.

11 Ibid. p. 49.

12 Ibid. pp. 171–9. See also Read, C., Culture and power in revolutionary Russia (New York: St Martin's Press, 1992)Google Scholar. There was a curious reference to this in a review of Youngblood's book by Peter Kenez, which seems to run counter to the thrust of Youngblood's conclusion.

13 Youngblood, , Movies, p. 178.Google Scholar

14 Stites, R., Russian popular culture (Cambridge, 1992), p. xiiGoogle Scholar. The review copy, interestingly, came with a hardback cover ‘Soviet popular culture’, and an inside page, entitled ‘Russian popular culture’. The perils of publishing since perestroika!

15 Ibid. p. 66.

16 Ibid. pp. 95–6 is an excellent discussion of this issue. Compare this account with the one put forward by Leszek, Kolakowski, Main currents of Marxism (Oxford, 1978), pp. 77–91.Google Scholar

17 The works on Soviet society together create a very complex picture of its essential features and values. See for instance, Gunther, H. (ed.), The culture of the Stalin period (London, 1990)CrossRefGoogle Scholar. Dunham, V. S., In Stalin's time: middle-class values in Soviet fiction (Cambridge, 1976)Google Scholar. See also the work by Robert, Thurston, ‘Fear and belief in the USSR's “Great Terror”: response to arrest 1935–39’, Slavic Review, XLV 2 (1986)Google Scholar, and in White, , New directions, pp. 160–88.Google Scholar

18 Stites, , Russian popular culture, pp. 208–9.Google Scholar

19 There are a number of important works which address this issue. Hosking, G., The awakening of the Soviet Union (London, 1990), chs I–IVGoogle Scholar; Lewin, M., The Gorbachev phenomenon (London, 1988)Google Scholar; Ruble, B., ‘Stepping off the treadmill of failed reforms’ in Balzer, H. D. (ed.), 5 years that shook the world (Boulder, 1991)Google Scholar; Bahry, D., ‘Society transformed: rethinking the social roots of perestroika’ in Slavic Review, LII 3 (1993), pp. 512–54.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

20 Siegelbaum, L., Soviet state and society between revolutions 1918–29 (Cambridge, 1992), p. 3.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

21 This is evident from the discussions in Russian Review, XLV and XLVI (1986) and (1987), where the notions of state and society were intensely debated, but without any real degree of conceptual rigour.

22 Ward, C., ‘The crisis of productivity in the New Economic Policy: rationalisation drives and shopfloor responses in Soviet cotton mills 1924–29’Google Scholar in White, , New directions, pp. 83–112.Google Scholar

23 Ibid. p. 96.

24 J. Hatch in ibid. pp. 113–24.

25 Siegelbaum, , Soviet state and society, p. 229.Google Scholar

26 Ibid. p. 214.

27 Ibid. pp. 224–5.

28 Ibid. pp. 225–6.

29 Ibid. pp. 63–6. Lih's original article was ‘Bolshevik razverstka and war communism’, Slavic Review, XLV (1986), pp. 673–88.Google Scholar

30 Siegelbaum, , Soviet state and society, pp. 213–14.Google Scholar

31 This was the scope of the debates in Russian Review articles mentioned above. See also the recent book: Getty, J. Arch & Manning, Roberta T. (eds.), Stalinist terror: new perspectives (Cambridge, 1993).CrossRefGoogle Scholar

32 For an astonishingly vitriolic review of the Arch Getty and Manning volume see Robert, Conquest, ‘Reluctant converts’ in Times Literary Supplement, 11 Feb. 1994, pp. 7–9.Google Scholar

33 Rittersporn, Gabor T., Stalinist simplifications and Soviet complications (Chur: Harwood Academic Publishers, 1991), p. 2.Google Scholar

34 Ibid. pp. 8–11.

35 Ibid. p. 18.

36 These points, and the general totalitarian debate, have continued for a number of years in an often acrimonious and heated atmosphere. See, for example, the exchanges in Russian Review, XLV and XLVI, and in particular the contributions from J. Arch Getty, D. Brower, W. J. Chase, S. F. Cohen, R. Conquest, G. Eley, P. Kenez and S. Fitzpatrick. In addition, the following articles have contributed a great deal to this debate: Fitzpatrick, S., ‘The Russian revolution and social mobility: a reexamination of the question of social support for the Soviet regime in the 1920s and 1930s’, in Politics and Society, II (1984)Google Scholar; Reichman, H., ‘Reconsidering “Stalinism”’ in Theory and Society, I (1988).Google Scholar

37 Rittersporn, , Stalinist simplifications, pp. 52–5.Google Scholar

38 Merridale, C., ‘The Moscow party and the socialist offensive: activists and workers 1928–31’ in White, (ed.) New directions, pp. 125–40Google Scholar. See also her excellent monograph, Moscow politics and the rise of Stalin (Basingstoke, 1990).Google Scholar

39 Rittersporn, , Stalinist simplifications, p. 89Google Scholar. The tensions within the Soviet factory have been well documented by a number of theorists. See for example, Andrle, V., Workers in Stalin's Russia: industrialisation and social change in a planned economy. (Hemel Hempstead, 1988)Google Scholar; Filtzer, D., Soviet workers and Stalinist industrialisation: the formation of modem production relations (London, 1986)Google Scholar; Kuromiya, H., Stalin's industrial revolution: politics and workers 1928–32 (Cambridge, 1988)Google Scholar; Rassweiler, A. D., The generation of power: the history of Dneprostroi (Oxford, 1988).Google Scholar

40 Thurston, R., ‘Reassessing the history of Soviet workers: opportunities to criticise and participate in decision-making 1935–41’ in White, (ed.), New directions, pp. 160–90.Google Scholar

41 Ibid. p. 179.

42 See the chapter in Rittersporn, , Stalinist simplifications, ‘Between two “Great Moscow Trials”: social tensions and political maneouvres, 1936’, pp. 64–112.Google Scholar

43 Merridale, , ‘The Moscow party…’ p. 137.Google Scholar

44 This general point about ‘social history’ approaches to an understanding of the 1930s was made by Kenez, and Eley, in their contributions to the debates in The Russian Review, XLV, 4 (1986).Google Scholar

45 Filtzer, D., Soviet workers and Stalinist industrialisation: the formation of modern production relations (London, 1986)Google Scholar. This is a marvellous analysis of Stalinist labour policy, and a fine account of the history of Soviet workers, written from a neo-Marxist standpoint.

46 Filtzer has a forthcoming volume on labour policy under Gorbachev.

47 Filtzer, D., Soviet workers and de-Stalinisation: the consolidation of the modem system of Soviet production relations 1353–64 (Cambridge, 1992), p. xi.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

48 Ibid. pp. 1–6.

49 Ibid. p. 3.

50 Ibid. p. 161.

51 Ibid. p. 17.

52 Ibid. p. 9.

53 There has been substantial debate about the factors which shaped the responses of the workers to Stalinist industrial practices. Filtzer argues that these were ‘rational responses to structural and political constraints’ (p. 158). Others have tended to emphasize pre-revolutionary and/or pre-industrial cultural values and patterns of behaviour. See ibid. p. 158, and also the reviews of Filtzer's 1986 work by Siegelbaum, L. in Slavic Review, XLVI, 2 (1987)Google Scholar, and Barber, J. in Soviet Studies (1988).Google Scholar

54 This point is well made in the introduction. See Edmondson, L. (ed.), Women and society in Russia and the Soviet Union (Cambridge, 1992), pp. 1–4.CrossRefGoogle Scholar

55 Nove, A., Studies in economics and Russia (Basingstoke, 1990)CrossRefGoogle Scholar. See also his excellent, An economic history of the USSR (London, 1969)Google Scholar. Nove has recently died. He will be sorely missed.

56 Lowenhardt, J., Ozinga, J. & van Ree, E. (eds.), The rise and fall of the Soviet Politburo (London, 1992)Google Scholar and Mawdsley, E., ‘Portrait of a changing elite: CPSU central committee full members, 1939–90’ in White, (ed.) New directions, pp. 191–206.Google Scholar

57 Lowenhardt, (et al.), Rise and fall, pp. 152–3.Google Scholar

58 Ibid. p. 18.

59 Ibid. pp. 51–2.

60 There are some notable exceptions though. See for instance the excellent work, Barber, J. and Harrison, M., The Soviet home front 1941–45 (London, 1991).Google Scholar