In his charmingly titled book A Geography of Time: The Temporal Misadventures of a Social Psychologist, or How Every Culture Keeps Time Differently, Robert Levine seeks to understand the sometimes striking global variations in timekeeping and attitudes to time. Studying “a people's temporal constructions,” he argues, presents “a precious window into the psyche of culture.”Footnote 1 The same is also the case with the past. E. P. Thompson, in his seminal article “Time, Work-Discipline, and Industrial Capitalism,” goes further than Levine. He contends that changes in how time was measured, enforced by manufacturing elites during the Industrial Revolution, brought about significant changes among the population. The working classes—to the economic advantage of those same elites—internalized the temporal reality that emerged in turn. In other words, the perception of time could be manipulated for the purpose of creating new cultural values.Footnote 2

This article seeks to apply this critical approach to medieval schools and to their engagement with time and other temporal practices. My work on this subject revolves around two central questions. First, what was the configuration of the medieval school day and year, and what gave them those forms? Second, what was the function of the school year and was such utility consciously recognized? I have found that schools and the authorities that controlled them—be they religious or secular—actively saw the school year as a tool with which they could socialize children and create and maintain collective community identities. By examining scholarship on socialization and medieval communities, the nature of the school day and school year, and the role of school-centered festivals, I hope to illustrate that the “temporal culture(s)” of the medieval school were intended to construct identities, hierarchies, and emotions that would prepare the children involved for roles in wider communities.Footnote 3

The word school can be applied to many different educational locales in the Middle Ages, including universities, and can describe the intellectual activities of monastic communities. The focus here, however, will be on schools that catered to children and that were introductory in nature. These schools were usually frequented by children between the ages of seven and fourteen (roughly). They provided instruction from the basics of literacy (alphabet, syllables, simple prayers and proverbs) to more advanced understanding of the Latin language (grammar, longer Latin texts, and composition). Occasionally, these schools may also have taught rudimentary arithmetic or the ars dictaminis (letter writing and other useful skills associated with working in business and administration).Footnote 4 While it is common to divide these educational activities between dedicated “elementary” and “grammar” schools—as with primary and secondary schools today—the line between these levels was often blurred in the documentary sources and in practice. For example, schoolmasters in later medieval Italy would charge different rates based on what a pupil was learning, but the different classes were still taking place in the same school, and sometimes in the same room.Footnote 5 It is convenient, therefore, to use the imprecise terms elementary and grammar education/schools/teachers as a catchall for this stage of education.Footnote 6 Due to the paucity of sources regarding private instruction within the home and other less-formal locales, this article will concentrate (mostly) on urban schools that were formally organized with statutes, regulations, and administrative oversight that would have generated paperwork.

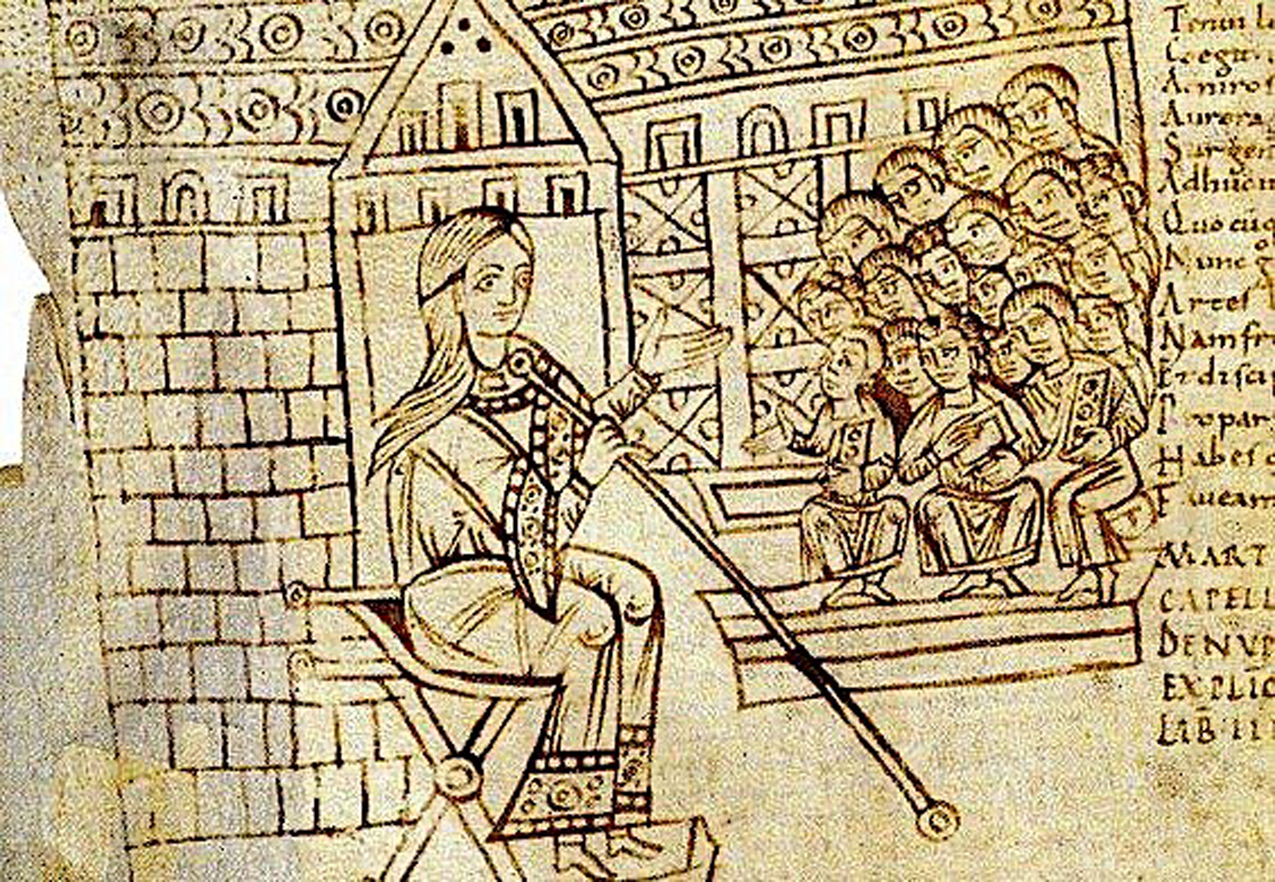

Figure 1. An ideal school. Tenth-century illustration of Grammar personified teaching a class. Source: Martianus Capella, La Grammaire et son amphithéâtre d'élèves, Manuscripts, Latin 7900 A fol. 127v, Bibliothèque nationale de France, http://expositions.bnf.fr/carolingiens/grand/lat_7900a_127v.htm.

For the most part, the focus here is on Western Europe from the thirteenth to the fifteenth centuries and on societies that were Latin Christian in adherence. Though striking variations exist even within this region, the significant cultural similarities justify studying them together. Where possible, evidence from other religious traditions (such as Judaism and Islam) will be discussed, but the meagerness of these references here should not be taken to suggest that these societies did not possess equally complex and conscious socio-pedagogical strategies. The focus is limited both geographically and chronologically to make a more coherent argument regarding the function of the school year, not to assert that Western Europe was singular in its use of schools to socialize children.

Socialization and Temporal Culture

Since this article seeks to explore the thorny issues of socialization, community, and identity, it considers some of the theories and arguments in these fields of inquiry. Modern sociological and psychological research has produced a range of approaches to the concept of socialization. Joel Mokyr, drawing on decades of scholarship, defines socialization as:

Any evolutionary approach to culture needs to be explicit about how culture is passed from one generation to the next, a process often referred to as “socialization.” Socialization occurs through direct imitation, often unconsciously so, or through symbolic means—spoken and written language, images, and examples.Footnote 7

Here, we meet the idea that socialization does not have to occur in an explicit manner, such as through legal systems or instruction in a classroom, but can equally happen through imitation and “symbolic means,” such as the structure of school terms or involvement in specific festivities. A medieval boy bishop and his companions were imitating their superiors, in a way that both subverted authority and integrated them into their ecclesiastical community.Footnote 8 Furthermore, Mokyr draws attention to the multiple types of socialization—vertical (from parents and other direct authority figures), horizontal (from peers), and oblique (from outside influences such as teachers).Footnote 9 The medieval school year and its festivals fostered an environment that allowed these modes of socialization to occur simultaneously. For example, terms and timetables were shaped by environmental factors but also by edicts of local authorities and the needs of parents. School celebrations developed at the point where youthful excitement and rebelliousness met their teachers’ and communities’ need to control and direct that energy but also their need to induct the young into their communities’ “temporal cultures”—marked by such things as the division of time and seasonal festivals.Footnote 10

And yet, youthful merrymaking should not be viewed as antithetical to grown-up order. Judith Harris's work on horizontal socialization by peers encourages us to look at child- and youth-led festivities in the Middle Ages in a fresh light.Footnote 11 Medieval pupils were just as keen to construct, manipulate, and succeed in school and community hierarchies that were either somehow directed by authorities (school, church, city) or were imitations of the same. We see this interplay between the marking of time and vertical/horizontal socialization occurring in the Ottoman Empire in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The state began to promote “Western” timekeeping practices in a bid to “modernize” Turkish society, and the emerging state education system was part of this campaign. According to historian Avner Wishnitzer:

Late Ottoman schools inculcated in their students a worldview that identified time thrift, punctuality, and temporal regularity with notions of progress and modernity. . . . The creation of elaborate temporal constructs based on standardized time blocks allowed for increased levels of surveillance of students and staff, and facilitated a more efficient pedagogical process. The same temporal construct served as an implicit curriculum, imbuing students with the novel practices and norms of modern time consciousness. . . . It will be clear that the unique time regime of late Ottoman schools pervaded the inner world of young students and to some extent scripted not only their behaviors but their emotions as well.Footnote 12

Here, vertical socialization—in this case, by the state—was implemented in schools, subsumed into youth behaviors, and then became part of horizontal socialization patterns.Footnote 13 I argue that similar patterns emerge in the construction of temporal cultures in the Middle Ages, where school authorities and school pupils cooperated—both consciously and unconsciously—and utilized time, its measurement, and its moments of punctuation in this process.

What is a temporal culture but a community? The study of the formation and maintenance of communities has been a particularly popular topic in the field of medieval studies. This is unsurprising, as it allows scholars to interact with medieval society on a variety of tangible and theoretical levels. It also permits researchers to consider the difficult issue of both individual and group motivation, which is helpful in answering our second question: what was the function and meaning of the school year and its festivals?Footnote 14 Looking at the temporal structures of the day and year in medieval schools will show how defining and constructing communities was interwoven into these practices and traditions. The section on “School Festivals and the Making and Maintaining of Communities” and the conclusion will provide further analysis of this process.

The Medieval School Day

Before examining wider trends in the medieval school year, this paper will briefly consider the medieval school day, as its forms were molded by similar forces, including the practical and the cultural.Footnote 15 Scholars such as Thompson, Wishnitzer, and Jacques Le Goff argue that the shape of daily time—and, by extension, the school day—is a locus of competing authorities seeking to control a society's perception of what time is and what it means: in other words, seeking to create temporal cultures.Footnote 16

The primary driving force behind the shape of the medieval school day appears to have been the availability of light. Teachers and pupils sought to make the most of natural light to avoid the added expense of candles and lamps.Footnote 17 And because of the changes in sunlight between winter and summer, the school day could contract and expand noticeably. Table 1 shows the medieval school day Nicholas Orme proposes based on fifteenth- and sixteen-century English school statutes.Footnote 18

Table 1. A late medieval timetable.

Source: Based on Orme, Medieval Schools, 143–44.

According to this timetable, school could last anywhere from six to ten hours, adjusting to daylight, the availability of artificial light, and if pupils had to travel from a distance.Footnote 19 But this also represents a particular category of schools which were heavily reliant on pupils who lived outside the school. On the other hand, pupils in monastic, cathedral choir, and boarding schools were generally in residence and the school day could continue into the evenings. In many statutes of these residential schools (cathedral, monastic), an evening session was a feature. At the cathedral school of Saint-Jean in Lyon, the evenings were set aside for a recordatio. The school statutes from 1357 state that each pupil had to meet with the master of the school and repeat what they had learned that day. It was also when praise and punishment were meted out for transgressions during the day.Footnote 20 Since these activities relied principally on listening and speaking, minimal use of candles or fires was all that was required. Another activity that was particularly important to monastic and cathedral schools was the teaching and learning of music. Unfortunately, there is little consistent information regarding the exact time this took place, except that it was expected to occupy a significant portion of the school day.Footnote 21 And much like recordationes, portions of musical training and practice could be pursued beyond daylight hours.

This brings us to secondary influences on the school day: the social and the cultural. Both Christianity and Islam developed set times for prayer throughout the day; this pattern shaped the marking of the hour in those societies and, by extension, in their schools.Footnote 22 In medieval Europe, the school days at monastic and choir schools were explicitly formed by the Divine Office and the pupils’ liturgical responsibilities, for example, as singers or holy water carriers. Children in these schools were often (but not always) intended for careers within the church and had effectively already begun these careers.Footnote 23 Patterning their learning on these services was both good preparation and inculcation for a whole life that would revolve around them. But the influence of the Divine Office extended beyond the cloister. The timing of religious service equally shaped the late medieval timetable, as described in Table 1: 6 a.m. was prime; the break for breakfast at 9 a.m. corresponded with terce, a connection emphasized by the fact that many schools held a prayer service or (occasionally) went together to a nearby church for mass at this point.Footnote 24

This daily framework, even in schools where teachers and children did not have overt liturgical commitments, demonstrates the power of custom and tradition. But it also reveals the power of sound. The ringing of bells in ecclesiastical institutions would have provided convenient markers for the beginning and end of teaching periods and breaks. For example, a fragment from a school exercise recorded by an assistant schoolmaster in Bristol around 1427 shows that schoolchildren divided their days based on the ringing of church bells: “We are in school every day fasting until nearly prime [because] of the clerk of the clock, to whom it falls to [be] busy in ringing the hours of the day.”Footnote 25

From the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, however, other institutions, such as municipal governments and guilds, developed their own auditory infrastructure guided by their own requirements. For example, in 1355, the royal governor of Artois gave permission for the town of Aire-sur-la-Lys to construct a bell tower where the bells would ring to indicate business hours and hours of work for clothworkers.Footnote 26 This opens up the possibility of alternative school timetables based on these bells.

Practical and sociocultural influences certainly shaped the school day, but does the timetable have function and meaning beyond the practical? As with the school year, the school day had the power to acculturate children into whichever community—religious, cultural, academic—they belonged, or sought to belong. This is obvious in the schools that were constituent parts of ecclesiastical institutions, such as choir and monastic schools. These children were already considered members of the monastic or cathedral community structures and so moved through their days in step with their adult colleagues. Even in schools not administered by a church, such as those controlled by Italian communes, the liturgical hours still shaped their days.Footnote 27 Along with dedicating prayer services within schools for the souls of departed benefactors, pupils became integrated into the wider ritual communities and the specific religious practices of their educational communities.

Forces Shaping the School Year

Much like the school day, similar forces, ranging from the practical needs of the natural and agricultural year to the demands of the religious and ritual year, shaped the school year. It also was affected by the school's location, by latitude and meteorology, and by local festivals and traditions. While no standard school year existed, these factors—light and heat, agricultural and economic requirements, and communal festivals—remain relatively consistent in type and, in the Middle Ages, shaped the school year across time and space.

As discussed earlier, the school experience was strongly influenced by the season, the availability of light, and the cost of heating, but these needs always existed in competition with other, especially agrarian, requirements. For instance, plenty of light in the summer meant little need for heating, but it also meant plenty of work to do in the fields. Then again, this was also the hottest time of the year and, at least among some medieval commentators, too much heat was not conducive for study.Footnote 28 Winter had fewer agricultural demands but much less light, and schoolrooms required heating. The medieval school year was created at a confluence of requirements (such as seasonal challenges and ritual duties) but it also demonstrates that authorities and communities harnessed the ungovernable tempo of time and nature for their own purpose—maintaining social cohesion by means of a temporal culture.Footnote 29

We see these requirements throughout the literary and documentary record. Municipal archives, school statutes, and family and institutional accounts show that lighting and heat were issues of concern. German school statutes from Landau (1432) and Schliezer (1492) required pupils to provide candles to their teachers from the Feast of St. Martin (November 11) onward.Footnote 30 In 1499, the municipal government of Lyon paid master Henri Valluphin 15 sols toward his heating costs.Footnote 31 The family of English schoolboy Edward Querton had to pay 1½ pence toward candles for the 1464–1465 school year.Footnote 32 Here we see local authorities and families using their resources to keep back the dark and cold; in other words, to overcome the limitations of the natural year. But what of the pupils whose families did not have extra money for candles and tallow? What about the independent teachers who were outside ecclesiastical or secular structures of power and patronage? These were at the mercy of dark winters, operating only when there was light to do so, and probably not at all during the coldest weather. It is also likely that some pupils stayed away when extras such as candles were demanded, though some statutes stated that only students who could afford to had to provide candles and fuel.Footnote 33

Educational theorists also considered heat and light and their effect on learning. Conrad of Megenberg (1309–1374) recommended that (in a perfect world) there should be two schoolrooms: a summer one, well ventilated with windows facing north, and a winter one, tightly enclosed so that it could be more effectively heated.Footnote 34 Thus children and teacher could press forward with their lessons no matter the weather. This sensitivity was informed by Conrad's use of humoral theory in his pedagogical advice. For example, he recommended that children who were starting school (at seven years of age) should do so in the spring, thus avoiding the damaging effects of the winter cold.Footnote 35 Conrad's scheme was idealized, however, and most teachers had to make do with what space they were given or had the funds for, making it difficult to circumvent the effects of the seasons.Footnote 36

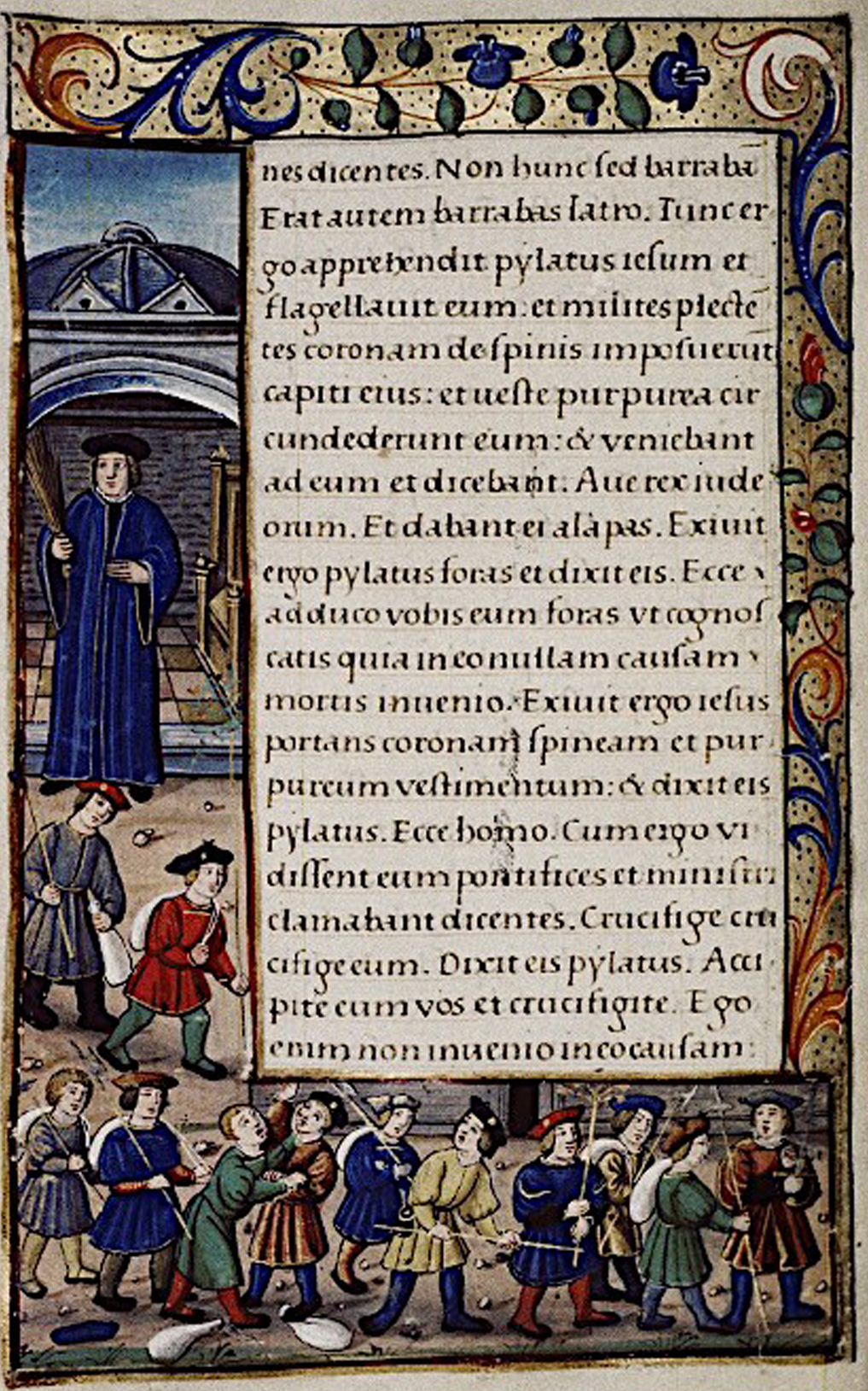

Figure 2. Some schoolchildren may have been called away during the summer months to assist with agricultural work, such as the haymaking depicted in this detail from the liturgical calendar for June. Source: Robinet Testard. Horae ad usum Parisiensem, known as Les Heures de Charles d'Angoulême, Manuscripts, Latin 1173 fol. 3v, Bibliothèque nationale de France, https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b52502694t/f16.item.

The agricultural year, also dependent on the seasons, deeply affected the school year, even though records show resistance to the demands of scythe and sickle. While it has been suggested that the long summer holidays common to universities in northern Europe originated from preexisting elementary and grammar school practices, there is some debate as to whether many schools had a “formal” summer break that coincided with the harvest.Footnote 37 David Sheffler states that Bavarian school statutes do not mention long summer breaks.Footnote 38 Paul Grendler's work on schools in northern Italy indicates that they effectively remained in session throughout the year and that communal governments like that at Volterra were proactive in keeping them open.Footnote 39 In late medieval England, however, lengthy summer breaks appeared to coincide with the harvest. The schoolmaster of Bury St Edmunds did not hold classes between Midsummer Day (June 24) and Michaelmas (September 29), while the schools of Wotton-under-Edge (founded 1384) and Newland (founded 1446) both had six-week vacations from August 1 to mid-September.Footnote 40 Likewise, Annemarieke Willemsen states that a long break was a feature of schooling in the late medieval and early modern Low Countries, with some vacations stretching from June to September, specifically to allow pupils to return home to help in the fields.Footnote 41

How can we account for these differences? First, as Sheffler argues, local customs and traditions may have facilitated the absence of pupils from classrooms when their families and communities needed their labor, and these may not have been reflected in statutes.Footnote 42 Furthermore, in parts of the Netherlands in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, more than half of the pupils would attend only one or two quarters each year—and the period between All Saints (November) and Candlemas (February 2) was the busiest. These children were likely outside working during the better weather and longer days.Footnote 43 This situation was not reflected in written regulations but was instead found in the rolls. Schooling continued, but for a smaller number of pupils. Second, schools like those in Wotton-under-Edge and Newland serviced a larger, more rural catchment area. They would have had to adjust the school year in order to fit into the rhythms of the local community. Meanwhile, though not cut off from rural life, the children in Volterra and other similar cities were predominantly urban and did not work in the fields.Footnote 44 But we must not be completely focused on how the different seasons affected agricultural activities; other work, such as building construction, was seasonal and not limited to the countryside.

There were, however, localized social and economic factors that determined if schools had summer breaks or not. Scholars at English public schools, such as Winchester College, did not have agricultural duties—they were either elites whose labor was not needed during harvest or scholarship boys who were already committed to professional or administrative careers—and did not need to take a formal summer break.Footnote 45 On July 12, 1370, the chapter of the Cathedral of Saint-Jean in Lyon instructed the boys of the school to begin preparing “the mass of the Cross and Blessed Mary,” that is, the liturgies for the Nativity of the Virgin Mary (September 8) and the Feast of the Cross (September 14).Footnote 46 On August 2, 1400, the choirboys were in residence as the chapter asked their master to be particularly kind to the boys due to a recent outbreak of plague.Footnote 47 Both these references suggest that these pupils did not have a summer break and were present and studying during August and September.Footnote 48 Finally, from an earlier period, the Colloquies of Ælfric Bata, while illuminating many aspects of pupils’ daily life in an Anglo-Saxon monastery, do not indicate any engagement with working in the fields. In one scene, the boys pick apples in the monastery's orchard, but this appears to have been for fun rather than work.Footnote 49 While agricultural requirements appear to have been a prime driver in the emergence of a long summer vacation that corresponded to harvest time in some regions, they did not dictate all school calendars everywhere.

Across later medieval Europe, the school year was divided into quarters. Each quarter or term began on, or just after, a significant feast day. Traditionally, these were Michaelmas (September 29), Christmas (December 25), Easter (a movable feast, but the term usually started on March 25) and Midsummer Day (June 24). Vacations of various lengths separated these terms. This pattern emerged in England, Germany, and Italy, but regional variations influenced the precise shape of these terms. And these variations demonstrate how local societal and communal priorities formed the school year.

As mentioned earlier, the midsummer term gradually disappeared in many English schools in the fifteenth century, reflecting the increased participation of children from agricultural backgrounds.Footnote 50 In German regions, the quarters were spring “beginning between Wednesday and Saturday in the week following Invocavit [the first Sunday in Lent], summer after Pentecost [between mid-May and mid-June], autumn after Kreuzerhöhung [the Feast of the Holy Cross] (14 September), and winter after St. Lucie (13 December).”Footnote 51 These dates reflect, for example, the prominence of carnival festivities, which were not as lengthy in England, with carnival in German and Italian areas acting as the break between the winter and spring terms. In Volterra, the commune granted a vacation of seven or eight days for carnevale—the longest in their calendar—but they struggled to limit it to that time frame.Footnote 52 School terms—and vacations—were expected to not only respond to local environmental conditions but also to the expectations and needs of local societies. As children grew up in these communities, when to work and when to celebrate were formulated by their families and neighbors, and then reinforced by the schools.

School-centered Festivals and Rituals

Holy days and festivals celebrated by the wider community were the principal dates that shaped the medieval school year, calling for a break from formal lessons.Footnote 53 For some of these, schools developed their own rituals. Boy bishop feasts and Shrovetide cockfights, for example, became youthful expressions of the wider temporal culture. While some of the special events that involved schools and schoolchildren likely emerged by happenstance, they endured across time and space because they contributed something important to children and to the communities of which they were a part. School festivals like the boy bishop, the boys’ king, Shrove Tuesday games, and the Virgatumgehen (the “festival” devoted to gathering switches for punishment) provided structured pauses from labor that still contributed to the conception, maintenance, and appropriate evolution of “community” that lay at the heart of these rituals.Footnote 54

The boy bishop feast, or the feast of Innocents, is probably the best-known school/child-related ritual of the Middle Ages. This feast was popular and observed in a variety of forms across Western Europe from its development in the tenth through twelfth centuries.Footnote 55 Widely discussed in a range of scholarship, only a brief description is needed here.Footnote 56 Originally, the boy bishop festival was centered in the schools directly attached to cathedrals.Footnote 57 On the Feast of St. Nicholas (December 6) or, alternatively, on the Feast of the Holy Innocents (December 28), a pupil was chosen to “become bishop” for the day. The boy bishop was chosen in different ways in different places. At Chartres, the boy bishop appears to have been chosen by the cathedral authorities; at Salisbury, he was elected by his fellow choirboys. He then was required to carry out the role of bishop, up to and including leading services in full episcopal garb.Footnote 58 He led processions, both within the cathedral precincts and beyond. These processions could be strictly liturgical or more like the procession of a lord and his court, providing entertainment and/or collecting donations. Often these delineations were not clear. The boy bishop had a full retinue, which always included fellow choirboys and pupils but also on occasion adult members of the cathedral community. The festivities ended with one of the Divine Offices (usually Vespers), and feasting at the actual bishop's expense was a regular feature. As Ronald Hutton and Max Harris note, the festival became increasingly rowdy, and by the fifteenth century frequently involved demanding monies with menaces, fighting, and even the occasional death. In Regensburg in 1357, one of the townspeople killed an adult canon accompanying the boy bishop on his procession through the city. Relations between cathedral and town deteriorated, the boys of the town were forbidden to associate with the pupils of the choir school, and “that game ceased, which is colloquially called the bishopric of the boys.”Footnote 59

So, what was the role of the boy bishop festival and the Feast of the Holy Innocents in socialization and the formation of communities? These rituals explicitly integrated choirboys in cathedral schools even further into the cathedral community. While they were already seen as “little clerics” and were active participants in the liturgy throughout the year, they were by necessity kept apart from their adult brethren.Footnote 60 The boy bishop festival allowed them to practice other roles in the ecclesiastical hierarchy—it could even be seen as a form of training. For example, one of the boy bishops chosen at Chartres during the bishopric of Guillaume de Champagne (1165–1176) later became bishop in his own right (Renaud de Mouçon, who was also Guillaume's nephew).Footnote 61

The selection of the boy bishop also tended to reinforce societal structures that were already in place. For example, Renaud de Mouçon, the boy who became bishop of Chartres in reality, was the nephew of Guillaume de Champagne, the then-bishop. As Hutton puts it, it was simultaneously a “rite of reversal” and a “celebration of norms.”Footnote 62 The boy bishop is a particularly fine example of concurrent vertical and horizontal socialization—taking place within and emphasizing the structure of the church while also allowing choirboys to take active roles in the process. It can also be read as a textual community, where the whole cathedral community interacted with the ritual and helped write and rewrite its corporate identity, increasing social cohesion. This was an intentional process. Boy bishop rituals were among a range of innovative liturgical practices that coincided with a growth in the number of clergy in Western Europe and a new and growing role for cathedrals in rapidly expanding urban landscapes. In other words, boy bishop festivals were the school-centered manifestation of a conscious program to fashion a new, reformed, and innovative ecclesiastical culture.Footnote 63

Epiphany (January 6), though a part of the Christmas celebrations, became a significant festival in its own right from the high Middle Ages. Religious services and feasting were—and continue to be—an important part of marking the visit of the magi to the infant Jesus.Footnote 64 Unsurprisingly, considering how “child-centered” the event was, with wise men and kings kneeling in homage to a baby, Epiphany accrued a special significance for children and was celebrated in schools. Willemsen recounts in detail the “children's king's feast” that was celebrated at a boarding school in Bruges at the end of the Middle Ages.Footnote 65 The day before, the school authorities would have enough white bread loaves made for each of the schoolboys. One of these loaves would have a large bean baked into it. On January 6, the pupils gathered to eat the bread and the one who got the bean would be proclaimed king and presented with both a crown and scepter. The “king” would preside over a dinner of special foods and drink from a mug of beer. Each time the “king” drank, the pupils would call out: “the king drinks!” After prayers and some playtime, the children went to bed.

What is interesting about the Bruges “children's king's feast” is that the ritual did not end with bedtime. Once the pupils were tucked in, the schoolmasters, the bakers, and the servant girls would gather and elect their own king and queen. On another day selected by the “royal couple,” and with the full approval and financial support of the school governors, a special, private feast would be held for the teachers and servants, “thus being happy and merry among themselves.”Footnote 66 This dual festival, with discrete but related rituals for both children and adults in the school, is a perfect example of the creation and maintenance of the school community itself. Not only were the pupils involved, but the rector, the teachers, and the support staff of bakers and servants were as well. They celebrated Epiphany not with their families but within the school, emphasizing bonds that would not have existed without the school. The apparently random choosing of the boy king was contrasted by the intentional election of the adults’ king and queen. It is difficult to interpret this difference in choosing but perhaps it was a conscious attempt to disrupt—even temporarily—hierarchies that had emerged among the pupils. Another noteworthy aspect is that the regulations indicate that this was to be a joyful yet controlled event. The stipulation that the adults’ revelry was to take place in private demonstrates that the school governors did not want the masters’ authority to be diminished in the eyes of their pupils, while still giving the adults a chance to relax together. Rarely do we find evidence like this of school authorities seeking to explicitly create group feeling among teachers, pupils, and support staff using the same festival.

The period before the beginning of Lent presented another moment of punctuation in the medieval school year. As in medieval society in general, carnival and Shrove Tuesday were major events, marked with a great deal of eating and rowdiness that sometimes descended into actual violence. For Italian cities, carnevale was the longest and most important of the school holidays. Such was its allure for youths, and its tendency to be celebrated earlier and earlier, that the commune of Volterra threatened to fine or imprison any student “who appeared with mask and drum” before the official beginning of carnevale.Footnote 67 Due to an air of permissiveness relating to general festivities, pre-Lenten rituals in schools tended to be more extreme, more violent, and more difficult to control. And yet they still presented an opportunity for socialization and increasing social cohesion.

Shrovetide's association with eating was common in medieval societies, since people were expected to consume those foods forbidden during Lent and which would not last until Easter, including meats, eggs, and cheeses.Footnote 68 Children and adults alike would enjoy dishes such as pancakes, which is commemorated in some surviving school exercises from the period.Footnote 69 However, cockfighting and ball games came to be explicitly associated with schools and pupils on the day before Lent began. One of the earliest and most famous descriptions of this is from William FitzStephen's life of Thomas Becket (late twelfth-century London): “Boys from schools bring fight-cocks to their master, and the whole forenoon is given up to boyish sport; for they have a holiday in the schools that they may watch their cocks do battle.”Footnote 70

Figure 3. Boys hosting a cockfight. Source: Livre d'Alexandre, 1338–1410, Bodleian Libraries, Oxford UK, MS. Bodleian 264, f. 50, https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/ae9f6cca-ae5c-4149-8fe4-95e6eca1f73c/surfaces/84b96590-d837-4a8a-95b1-61c8f6177f3c/

But this was not just an English tradition and was attested in both the Low Countries and France. The association between schools, cockfighting, and Shrovetide was so engrained in the late medieval imagination that images of these activities in prayer books were used to denote the month of February. For example, the liturgical calendar entry for February in the Book of Hours made for Marie-Adélaïde of Savoy in the late fifteenth century is lavishly illustrated with schoolboys running a cockfight with their schoolmaster (see Figure 4).Footnote 71

Figure 4. Schoolboys and their teacher hosting a cockfight, possibly in their schoolroom. Detail from the liturgical calendar for February. Source: The master of Jean Rolin, Heures d'Adélaïde de Savoie (1460–1465), Musée Condé, Chantilly, France, MS 76, f. 2v, BVMM - CHANTILLY, Bibliothèque du château, 0076 (1362), f. 002v - 003 (cnrs.fr).

The same illustration shows boys playing a stick-and-ball game—perhaps a forerunner to croquet or golf—which was another popular activity on Shrove Tuesday. FitzStephen's description of this event went on to indicate:

After dinner all the youth of the city goes out into the fields to a much-frequented game of ball. The scholars of each school have their own ball, and almost all the workers of each trade have theirs also in their hands. Elder men, and fathers, and rich citizens come on horseback to watch the contest of their juniors, and after their fashion are young again with the young.Footnote 72

Cockfights and raucous ball games had the potential for danger and violence. The Corporation of London had to ban the Shrovetide football games in 1314 and, in 1409, prohibited the “forcible levying” of money from people on the streets by youths determined to raise money for the best cocks and for gambling.Footnote 73

Figure 5. Youths playing a stick and ball game. Detail from the liturgical calendar for February.

Source: The master of Jean Rolin, Heures d'Adélaïde de Savoie (1460–1465), Musée Condé, Chantilly, France, MS 76, f. 2v, BVMM - CHANTILLY, Bibliothèque du château, 0076 (1362), f. 002v - 003 (cnrs.fr).

These violent and rebellious acts, however, did not lie outside local temporal cultures, nor did they oppose socialization efforts. Hutton argues that pre-Lenten rituals were wild throughout the communities that celebrated them because it was the last time to have fun before the penitential requirements of Lent itself. Additionally, as food reserves had been depleted over the winter, “an opportunity for the frenetic release of emotion would have been very welcome.”Footnote 74 Such wildness was part of how people marked the season and children were granted similar license. By seeking to contain these events within the activities of the school as a group and under the supervision of teachers, a modicum of order could be maintained. Some schoolmasters even managed their pupils’ gambling: if the boys did not pay what they owed, they were denied recess until they did.Footnote 75 There were consequences, and a balance between work and play had to be struck. Despite the outward violence of the rituals, they also appear to have created an emotional community between the adults who had once partaken in them and the schoolchildren. As FitzStephen wrote, older men came to watch the ball games “and after their fashion are young again with the young.” Not only did the event create an intergenerational bond of experience but it also allowed the elders to indicate that these ball games were an appropriate “mode of emotional expression.”Footnote 76 Though the most ferocious of the medieval school festivals, Shrovetide cockfights and ball games seem imbued with a strange nostalgia and endure much longer and in a more consistent format than the others discussed here.Footnote 77

At the end of April (St. George's Day) or on May Day, teachers and pupils in places across northern Europe took another holiday, leaving their schoolrooms together and progressing out to the fields and woods (see Figure 6). These processions were so common that, much like the cockfights and ball games, books of hours from Ghent and Bruges included these images to indicate the month of May.Footnote 78 But the purpose of these outings was not for relaxation nor even to gather spring vegetation for decorations, though it likely grew out of such activities.Footnote 79 Instead, it was to gather rods and switches for disciplining pupils throughout the year.

Figure 6. Schoolboys in a procession with their teacher. Source: Book of Hours. Use of Rome. Early 16th century. Bodleian Libraries, Oxford UK, Bodleian Library MS. Douce 276, f. 10 v. https://digital.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/objects/ccc9f02f-96a8-4bbd-8cf4-5feaa1ae43a5/surfaces/06911f26-1ca2-496e-b640-85a52965754c/.

Particularly popular in German-speaking areas, the Virgatumgehen—literally, going for the rods—may have appeared as an answer to the increasingly problematic boy bishop festivals.Footnote 80

The rituals associated with the Virgatumgehen were relatively simple. Teachers and pupils would progress out of their school and through the town and city, and back again at the end of the day. The group sang and played musical instruments, and the local community came out to view the event.Footnote 81 One song preserved from late medieval Eppingen underlies the purpose of the day: “Behold, now, fathers and sweet mothers, how we return, loaded with birch-wood which may serve us well, working to inspire usefulness, but not injure.”Footnote 82

The whole day might be spent out in the fields and woods, collecting rods but also playing and generally having fun. As with any excursion into nature, there were dangers. In 1426, two pupils from the Alte Kapelle school in Regensburg drowned while swimming in the Regen River.Footnote 83 There is little evidence of real disturbances during these events, and local authorities looked upon the processions with favor.

The Virgatumgehen is a good example of a preexisting festival that was co-opted for pedagogical purposes. Even the primary activity of the day—the gathering of garlands and greenery—was only slightly adjusted so that “the vegetation collected by children was now put to work making [rods] for use in their instruction.”Footnote 84 The children were actively involved in making the tools for their own chastisement. While the festival masqueraded as an organic offshoot of a popular ritual, it is a case study in vertical socialization since the teachers “made” the pupils get the rods. Like the boy bishop festivals, pupils internalized the event and made it a joyous occasion. Unlike the boy bishop festival, however, it does not display elements of horizontal socialization. It reinforced the roles of the master as disciplinarian and the pupils as those deserving of punishment.Footnote 85 It also reinforced the hierarchies in school communities and—since families and local authorities approved—it strengthened those hierarchies too. If we read this ritual as a text, the Virgatumgehen “provides for the social identity and cohesion of the entire community” by having pupils tacitly accept the corrective forces their community supported.Footnote 86

School Festivals and the Making and Maintaining of Communities

Turning back to our consideration of socialization and the development of communities and identities, the temporal cultures of the school year we have examined here are both making communities and maintaining communities. Any given temporal culture can also be seen as a community in its own right, with its rules, traditions, and sense of membership. In the context of the wider scholarship on medieval communities, we can read medieval schools and their temporal practices as textual communities or communities of discourse, or even as emotional communities.

Of course, the timing of a school term or an Epiphany celebration was not a “text” in the strict sense of that word. Brian Stock, the first to formulate the concept of a “textual community,” sought to be intentionally vague in defining the term.Footnote 87 A school ritual could be a text, and creating and participating in it led to the formation of a community. Interpreting and interacting with these temporal practices “provides for the social identity and cohesion of the entire community.”Footnote 88 “Communities of discourse” is a related model but emphasizes the learned aspects of involvement with the community in question:

Membership in a discourse community is taught, just like the membership of an interpretative community and—presumably—that of a textual community. It requires knowledge of the register, concepts, and expectations of the group—knowledge that can be acquired through training. Lack of training, or disagreement with the discourse that centers on the community's texts, essentially excused the individual from the discourse community.Footnote 89

This can be applied to the socialization function of the medieval school year. Each child was required to learn and to fit into its structure, and thus became an active participant in maintaining that structure. As a result, the structure was perpetuated and its function to create members who would fit into the local community was deemed to have succeeded. Likewise, the unruly child or misfit could be acculturated or rejected depending on their involvement in—or elimination from—the court of the boy bishop, for example.Footnote 90 The same structures and events could also help shape the “emotional communities” Barbara Rosenwein proposes:

It is a group in which people have a common stake, interest, values, and goals. [They] are largely the same as social communities—families, neighborhoods, syndicates, academic institutions, monasteries, factories, platoons, princely courts. But the research looking at them seeks above all to uncover systems of feeling, to establish what these communities (and the individuals within them) define and assess as valuable or harmful to them (it is about such things that people express emotions): the emotions that value, devalue, or ignore; and the modes of emotional expression that they expect, encourage, tolerate, and deplore.Footnote 91

This is a useful point from which to approach medieval school festivals in particular, especially those containing elements of misrule or “reversal.”Footnote 92 School-sanctioned cockfights, football matches, and so on provided a release for pent-up emotions but also gave them the correct shape in the correct space at the correct time. The medieval school year, therefore, can be seen as an emotional framework as well as a temporal one, helping to cultivate emotional and temporal cultures.

By fashioning and engaging with a temporal culture, schools could make themselves into discrete communities that could interlock and overlap with other communities. As Rosenwein proposes, medieval society was made up of “a large circle within which are smaller circles, none entirely concentric but rather distributed unevenly within the given space.”Footnote 93 Perhaps we can adapt this analogy by seeing these “circles” as cogs that interlink with each other in order to power larger societal structures. In other words, all these communities working together helped society in general to function.

Conclusion

Medieval people, from the lowest peasant to the most learned cleric, were acutely aware of the passage of time and the seasons. They could not ignore its physical manifestations, such as seasonal weather patterns and changes in the length of the day, which governed the shape of the school year and its moments of punctuation, its festivals. But medieval people also knew that time, at least how they measured and used it, was a flexible and evolving construct. In his work on the effects of the emergence of clocks on timekeeping, Gerhard Dohrn-van Rossum acknowledges:

In medieval understandings, . . . the division of time, and especially of the day, was not simply a given fact, beyond doubt and unchangeable. Instead, it was seen as determined in part by natural rhythms, in part by social convention or “political” decisions, and as subject to historical change.Footnote 94

The school year—observably shaped by social convention and subject to historical change—was both an expression of this fluidity and a tool that could build time discipline and temporal cultures. Time was, as Le Goff asserts, pliable.Footnote 95

If time was pliable, then it could be used. And if time was an instrument, motivation was required to wield it for a desired outcome. The temporal culture that the school year represented was a consciously constructed framework that was intended to have a function. The evidence presented in this article argues that this function was to socialize children and to create and maintain social cohesion. Learning to adhere to the time discipline of the school day and the academic year was one way to inculcate children and youths with the capacity to operate effectively in the wider communities. School festivals were linked to those celebrated in the wider communities, allowing children a chance to take on adult roles. These festivals also permitted pupils an emotional and physical release, but in a contained and guided manner. Ultimately, despite the apparent anarchy of some of these events, they served to reinforce communal bonds. As scripture states: “To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven” (Ecclesiastes 3:1). Time and its measurement and rhythm had a purpose in the medieval school.