INTRODUCTORY ISSUES AND HISTORICAL CONTEXT

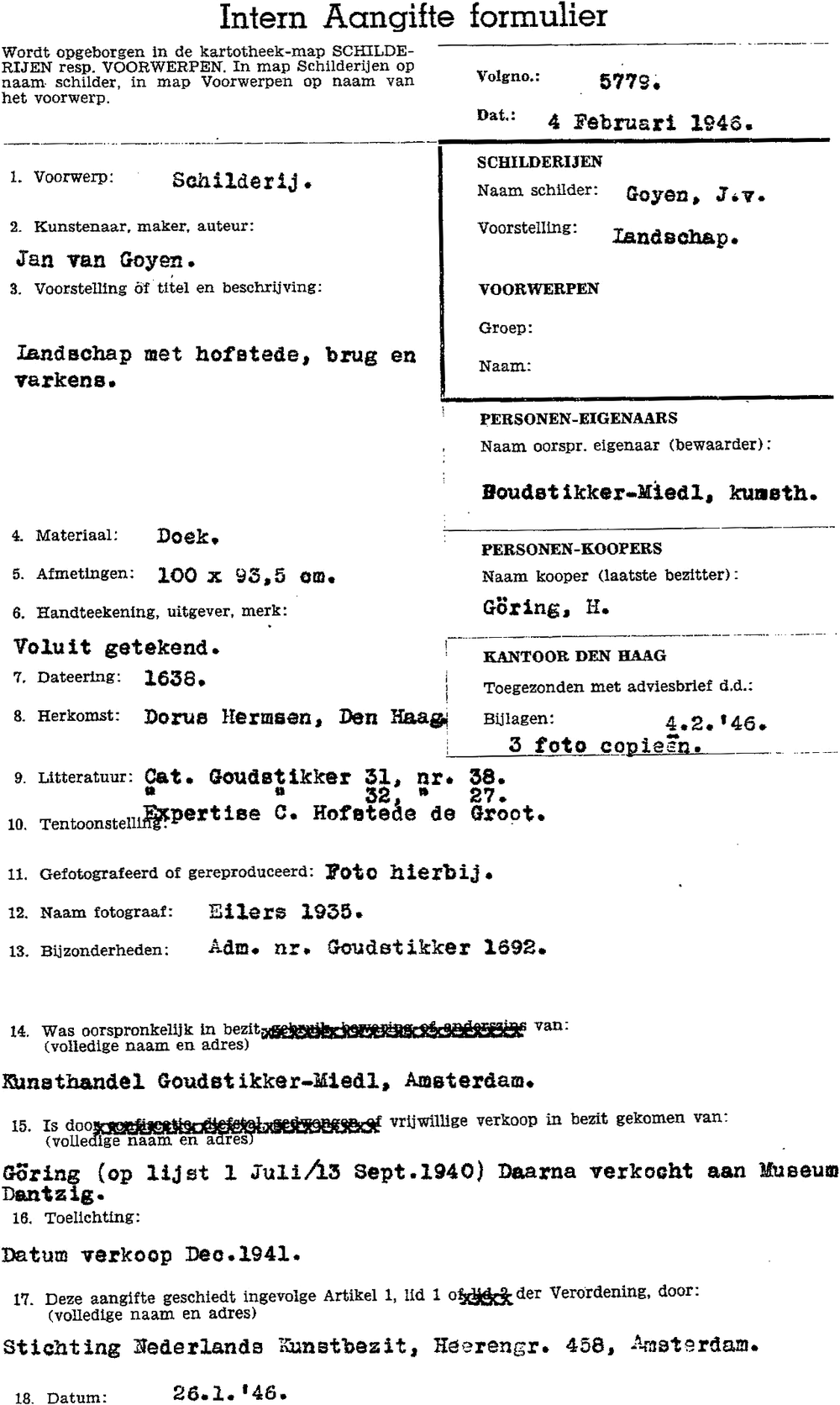

Twenty years after the Washington Principles, and ten years after the Terezín Declaration, this article traces the provenance and wartime migration of a charming painting by Jan van Goyen (1595–1656), now hanging in the Muzeum Narodowe in Gdańsk (one of Poland’s National Museums), but still “missing” since World War II from the Collection of Jacques Goudstikker (1897–1940) (see Figure 1).Footnote 1 As an initial, practical purpose, this article first serves to correct my earlier published allegation in this journal (and in a Czech conference presentation) that Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring (1893–1946) had sold this painting to Erich Koch (1896–1986), Gauleiter and Oberpräsident of East Prussia in the fall of 1940.Footnote 2 Accordingly, in turn, it corrects that erroneous allegation (and several others) in the US Office of Strategic Services (OSS) Art Looting Investigation Unit (ALIU) 1945 “Consolidated Investigation Report no. 2: The Goering Collection” (“CIR: Goering Collection”), thus calling for further scrutiny of such oft-quoted sources.Footnote 3

Figure 1. Jan van Goyen (1595–1656), Huts on a Canal (Chałupy nad kanalem in Polish), Muzeum Narodowe, Gdańsk, 1638. Earlier River Landscape with a Swineherd; Landschap met Hofstede (Brug en varkens, Goudstikker BB no. 1692), sold to Albert Forster, Gauleiter of Danzig for the Stadtmuseum in December 1941, following Alois Miedl’s takeover of the Goudstikker Gallery, Amsterdam (courtesy of the Muzeum Narodowe, Gdańsk; see https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Goyen_Cottages_by_the_canal.jpg [accessed 4 November 2019]).

Simultaneously, while fulfilling that immediate corrective purpose, this analysis presents an example of the wartime trans-European migration of a Dutch painting of prewar provenance in the collection of a highly respected Dutch Jewish dealer in Old Masters, which, following “red-flag” Nazi elite “purchase,” first by German banker Alois Miedl (1903–90) and then by Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, was sold by Miedl’s Germanized Dutch firm of Goudstikker-Miedl (with two other Dutch paintings) to the National Socialist (NS) Gauleiter of Danzig (now Polish Gdańsk), Albert Forster. That sale in December 1941 was a year later than Göring was erroneously reported to have sold the painting to Gauleiter Koch.

The complicated trans-European migration of this painting (and those that travelled with it) is better understood with a bit of historical context. Between 1918 and 1939, Danzig was a Free City, with a large German population and strong German pretensions; Albert Maria Forster (1902–52) was named Gauleiter (a function of the National Socialist German Workers Party [NS]) already in 1930. The initial German invasion of the Polish Corridor (1 September 1939), with the bitter battle for the Polish munitions depot of Westerplatte at the Danzig harbor entrance, was the first step in the invasion of Poland at the start of World War II (80 years ago). Gauleiter Forster, who then helped engineer the annexation of the Free City of Danzig and the Polish Corridor to the German Reich, became the Reichsstatthalter (governor) of Danzig-West Prussia. He brutally pursued Germanization and extinguished the large Jewish and Polish population, as well as Poles throughout the area. He lavishly promoted Nazi art preferences in the Municipal Museum (Stadtmuseum), which became a gathering place for Nazi-looted works of art during the war. With the Red Army “liberation” of Danzig in March and April 1945, which left the city in rubble, Forster fled to the Hamburg area that became part of the British Occupation Zone. The British captured and extradited Forster to Poland, where he was condemned to death for war crimes in 1948 and hanged in Warsaw in 1952.

In the fall of 1941, Forster personally journeyed to the Netherlands and, in December, purchased the van Goyen (along with the two other Dutch paintings) in Amsterdam from Alois Miedl (that is, Goudstikker-Miedl). The van Goyen (and the other two) were registered in the Danzig Municipal Museum (Stadtmuseum), among no fewer than 29 works of art “purchased” in the occupied Netherlands through 1944 by Forster and/or the Danzig museum director Willi Drost (1892–1964), along with others acquired elsewhere. The van Goyen in focus here, as we shall learn, was twice evacuated from Danzig; the second 1944 evacuation was to a castle in Thuringia (in the postwar Soviet Occupation Zone), where it was captured by one of Stalin’s “trophy brigades” in 1946. After a 10-year sojourn in the Hermitage (thus avoiding postwar Dutch claims), the painting returned to Poland in 1956. Meanwhile, with the Potsdam Agreement (August 1945), Danzig (with its Polish name Gdańsk) had become part of Poland with its extended western frontier.

Tracing more details of the wartime and postwar odyssey of this painting simultaneously highlights several important issues deserving attention today in provenance research for still-displaced Nazi-looted art. First, it shows an example of the Polish government’s silence and neglect of potentially “red-flag” wartime cultural acquisitions by Nazi elite currently held in Poland; the lack of needed transparent provenance research on such NS-period acquisitions, especially in cities annexed to the NS-period German Reich; and an unwillingness to deal with potential claims, especially from Holocaust victims, according to European Union (EU) and other international agreements and resolutions that the Polish government has signed.

Since the fall of the Communist regime, and given the extensive Polish wartime cultural losses, Polish government attention and tremendous funding has been devoted (successfully) to the retrieval of many Polish cultural losses abroad. However, Poland still offers no reciprocity in terms of its willingness transparently to identify Nazi-looted (including illegally purchased) and otherwise displaced foreign-owned cultural property acquired during the NS regime that is now in state museums. This Danzig case may focus on one important painting from a well-known collection in the Netherlands, purchased during the war (with two others) by the Nazi Gauleiter of Danzig-West Prussia, but it reflects a much larger problem: Poland still lacks a viable procedure for processing restitution claims from Holocaust victims throughout the country and from abroad. No wonder that, in 2014, Poland was listed by the Claims Conference among those Eastern European countries “that do not appear to have made significant progress towards implementing the Washington Principles and the Terezín Declaration.”Footnote 4

Second, the article also contrasts the recent neglect by the Dutch government in continuing to seek repatriation and restitution of cultural losses belonging to private Dutch Jewish owners (including, in this case, a prominent Dutch Holocaust-victimized dealer). Dutch authorities claimed the van Goyen painting (and the two others sold with it) during the immediate postwar years (as will be shown below), along with at least 23 others purchased by Danzig Nazi officials on the wartime Dutch art market, but, at that time, the van Goyen, along with many other Danzig purchases from the Netherlands, had been captured by a Soviet trophy brigade near Gotha, East Germany (where they were evacuated from Danzig).

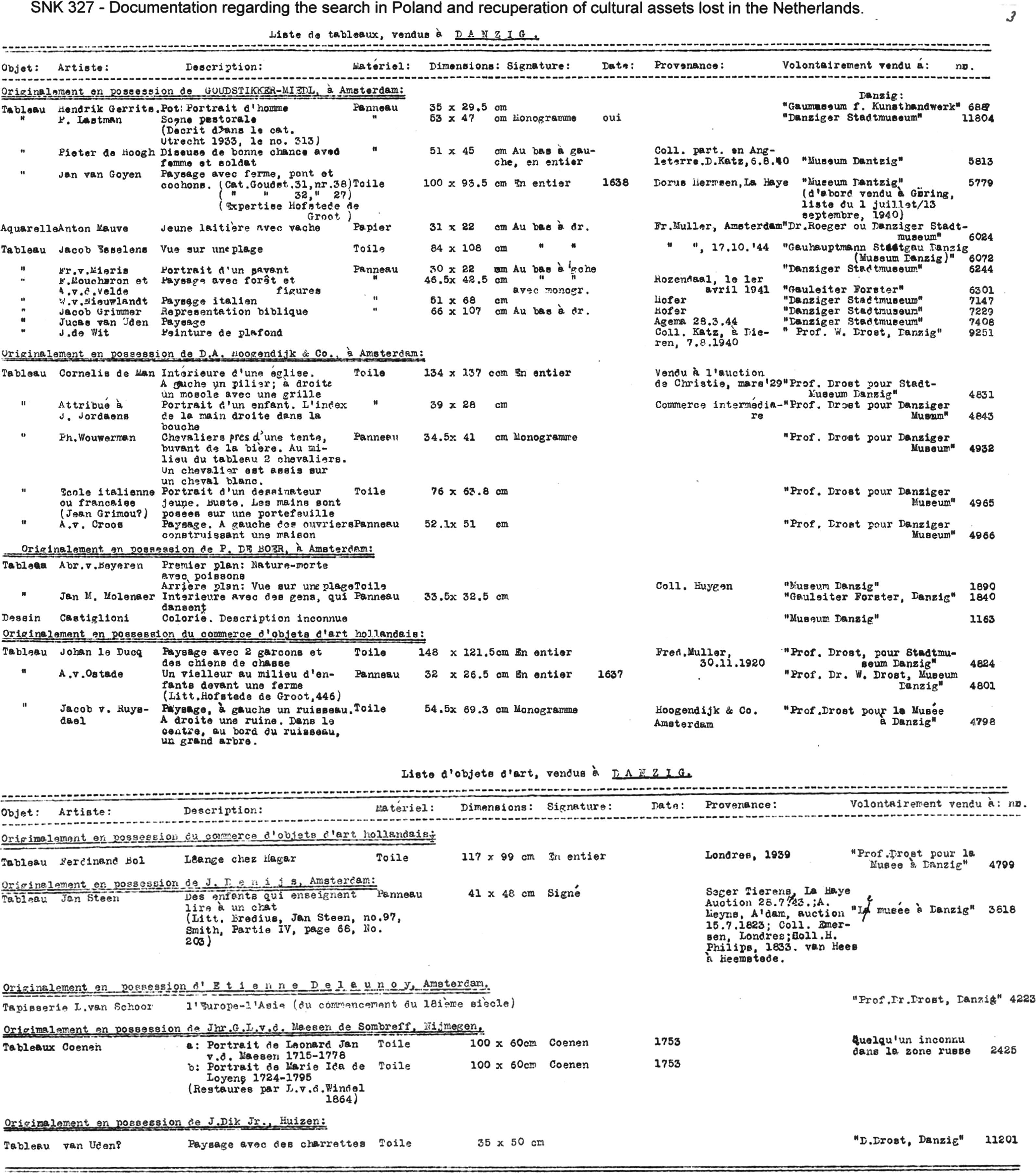

To Dutch credit, the postwar Netherlands Art Property Foundation (Stichting Nederlands Kunstbezit [SNK]) had one of the most detailed registration systems of any victimized country for individual wartime art losses, public and private.Footnote 5 Already in 1946–47, an SNK compilation lists the van Goyen among 29 “missing” works of art sold by various Dutch dealers during German NS occupation to the Nazi governor and museum director in Danzig (see Figure 11), along with 25 sold to art dealer Galerie Steinecker in Posen (now Polish Poznań), nine paintings purchased by Nazi leaders for the Germanized museum in Breslau (now Polish Wrocław), and five to a collector in Liegnitz (now Polish Legnica). Further provenance research is needed about those art works, many still presumed to be in Poland, listed with dealers from whom they were purchased, and many with the names of their original Dutch owners.Footnote 6 The van Goyen painting was also listed (among others on that SNK list) on Dutch claims to US restitution authorities in Germany. The recently launched database of the Bureau Herkomst Gezocht (BHG) / Origins Unknown Bureau, together with online databases of the RKD-Netherlands Institute for Art History / Nederlands Instituut voor Kunstgeschiedenis, provide exemplary sources for provenance research on these and other Dutch-owned and still displaced works of art.Footnote 7

Finally, the above issues, woven together within the narrative that follows, serve as a call to arms for more careful provenance research, especially with attention to forced or “red-flag” wartime sales, and for the need to verify the reliability of otherwise trusted sources. And they also reflect a hope that Polish authorities will begin to realize that foreigners would be much more sympathetic to the retrieval of Polish lost cultural valuables (amidst the horrific Polish wartime losses) if Polish authorities would offer reciprocity and show a bit of sympathy for other Nazi victims, in identifying the provenance and honoring claims for foreign-owned wartime losses and “missing” art and other cultural property now in Poland.

GÖRING’S ALLEGED SALE OF THIS GOUDSTIKKER VAN GOYEN TO ERICH KOCH DENIED

According to the “CIR: Goering Collection,” in the fall of 1940, Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring sold to Erich Koch, Gauleiter and Oberpräsident of East Prussia, a painting by Jan van Goyen, River Landscape, from the Goudstikker Collection.Footnote 8 Now known in Polish as Chałupy nad kanalem (Peasant Huts on a Canal and, earlier, as River Landscape with a Swineherd or Landscape with Peasant Farm), I admired the charming painting in the summer of 2014 as it hung proudly in the Muzeum Narodowe in Gdańsk (Danzig in German), where Polish colleagues had kindly arranged for my visit (see Figure 1). It is the only van Goyen in Gdańsk, a former Hanseatic port with close medieval and early modern ties to the Netherlands.

When I presented my paper about the paintings from the Koch Collection now “hidden in the Hermitage” at a workshop in Berlin in 2016, with due respect to our Berlin workshop sponsors from the Polish Ministry of Culture, I concluded my presentation with a few remarks about this van Goyen painting now in Gdańsk. I introduced it as “the only painting in the Koch Collection that I had actually seen” and one that had emerged after a 10-year sojourn “hidden in the Hermitage.” Now, with the correction that it had never belonged to Erich Koch, it falls into a different category than the twice-looted paintings that Koch had appropriated from French and Dutch dealers and a Kyiv museum for his personal collection in Königsberg, but that have yet to emerge from hiding (presumably still in the Hermitage) after similar postwar capture in East Germany. The images I showed of the painting included the verso with its stretcher bearing a well-preserved Goudstikker label and a visible number 1692. In discussion thereafter, Nina Senger, a German provenance researcher with Christie’s, cast serious doubts on my claim of Göring’s sale of that painting to Koch, also questioning its inclusion in the Koch Collection, as I had also alleged in a 2015 article in this journal.Footnote 9 Thus, Senger also cast doubt on the same allegation in the postwar “CIR: Goering Collection.” The account that follows is in part an effort to correct those allegations with more extensive research and consultation.

The alleged sale to Koch, according to the testimony of Göring’s principal art curator, Walter Andreas Hofer (1893–1971), supposedly took place after Göring’s newly acquired Goudstikker paintings arrived in Berlin. However, instead of selling the painting to Koch as Hofer had suggested, the van Goyen painting in question here, now known as Peasant Huts on a Canal, in fact went to the auction block in Berlin in December 1940, as Senger suggested, together with other paintings, in what has been termed the “Old Goudstikker” inventory that Göring did not appropriate for his own collection. Then, despite its reported sale in that Lange Berlin auction, as we shall see, the painting returned to Amsterdam in 1941 to the former Goudstikker Gallery then controlled by Alois Miedl.

My attention to this van Goyen painting and my trip to Gdańsk to pursue more data about the Koch Collection, were part of my attempt to verify the paintings that Göring had sold to Erich Koch as Gauleiter of Königsberg and Präsident of East Prussia, and whom Göring subsequently recommended as Reichskommissar of Ukraine. My research about the hitherto unknown collection of Nazi-looted art that Koch brought together on his palatial estate outside of Königsberg started in 2009, when I found reports about the Soviet removal of remains of the Koch Collection from a Weimar bank in the fall of 1948, among recently declassified documents in a Moscow archive. The Hermitage curator who was involved claimed that Koch had stolen all of the paintings from Ukraine. I had recently published an article about the massive collection of art from Kyiv that Koch had ordered be taken to Königsberg in the fall of 1943 during the German retreat from Ukraine. I had earlier assumed that almost all of those paintings had been intentionally destroyed on a German estate south of Königsberg when the Red Army arrived in February 1945.Footnote 10 Could these Koch paintings that the Hermitage curator found in Weimar possibly be Ukrainian survivors?

In the meantime, I have uncovered and scrutinized several lists of Koch’s personal collection deposited on his behalf in Weimar by his Schutzstaffel (SS) estate manager from Königsberg in February 1945. I reviewed the Hermitage’s published documents about the arrival of the Koch paintings in Leningrad in early 1949, as well as the original archival files on which the publication was based. Those lists and Hermitage reports, together with additional archival documentation in Moscow, Berlin, and Weimar, have enabled me to reconstruct considerable details about the Western (Dutch and French) provenance of many looted paintings in that collection and the postwar fate of some of them. As will be clear from what follows, other than the “CIR: Goering Collection,” there is no evidence that the van Goyen painting that I saw hanging in Gdańsk was ever part of Koch’s collection of looted art.

GOUDSTIKKER PROVENANCE DENIED AND CONFIRMED

More careful provenance research is needed today by museums throughout the world, especially for their wartime acquisitions, to assure the public that the legitimate property of Holocaust victims is not hanging on their walls or hidden away in their storage rooms. Apparently, that has not been a concern for the National Museum in Gdańsk; even since my 2014 visit, the director Wojciech Bronisławski, who received me, was in place through 2019. To my knowledge, he never revised his denial of the Goudstikker provenance of the van Goyen hanging in the museum, but we can hope the situation will change with a new director starting in January 2020. Images of the many paintings needing transparent provenance disclosure on the basis of their wartime purchase by the Nazi museum director and the Gauleiter of Danzig were earlier displayed on the museum website, but are no longer pictured there five years later.Footnote 11 Provenance research has recently become a more serious issue in the context of Nazi art looting, given the plentitude of “forced” or dubious art sales and Nazi elite “purchases” during World War II and recent claims by Holocaust victims. The need for such research and transparency about wartime acquisitions is even greater in Poland, which is one of the former Eastern Bloc countries now in the EU that has not enacted a viable claims procedure for tainted cultural property illegitimately purchased from another EU member country during the war, especially the property of Holocaust victims.

The present case study also provides revealing examples of inconsistent sources that may be involved, complicated by opposing attitudes of those who apparently deny the need for such transparency about provenance; in this case, the unwillingness of a Polish museum director to look beyond the immediate wartime purchase on behalf of his predecessor, a Nazi museum director. When I first visited the Muzeum Narodowe in Gdańsk in the summer of 2014 on the trail of suspected looted paintings that Koch had “purchased” from Göring, I was gratified that a meeting could be arranged with the Museum director, Wojciech Bronisławski. During our first encounter, Bronisławski emphatically denied any Goudstikker or Göring connections for the van Goyen painting in question. Even before my arrival, a Gdańsk colleague had sent me a newspaper reference in which Bronisławski had earlier denied any Goudstikker or Göring connection to a local journalist. However, neither he nor his staff could provide an alternative provenance for the painting, claiming only that “it was purchased by the wartime Danzig Museum director Willi Drost on the Dutch art market,” as if that fact legitimized the museum acquisition.Footnote 12

Yet during that same visit, the museum curator of Dutch and Flemish paintings, Beata Purc-Stępniak, kindly presented me with a compact disc with several quality images of the van Goyen painting, including its verso with the Goudstikker label intact on its stretcher. That label immediately confirmed my homework before arrival in Gdańsk and, hence, led me to quite a different conclusion than the museum director had presented; even the Goudstikker no. 1692 I suspected was still clearly visible on the label (see Figure 2).

Figure 2. Jan van Goyen—Goudstikker label on stretcher—with Black Book no. 1692 (courtesy of the Muzeum Narodowe, Gdańsk).

GOUDSTIKKER PROVENANCE FURTHER CONFIRMED, EVEN WITHOUT KOCH

Aside from Theodore Rousseau’s listing in the “CIR: Goering Collection,” based on Walter Andreas Hofer’s assertion, I have found no evidence that Göring sold the van Goyen to Koch or that the painting was ever in Königsberg. No van Goyen appears on the list of paintings deposited on Koch’s behalf in Weimar in February 1945.Footnote 13 Yet, quite coincidentally, as I have since learned, at the time of Koch’s Weimar deposit, the van Goyen in question was a little over 50 kilometers (30 miles) from Weimar—among the 53 paintings evacuated from Danzig and deposited in 1944 in Schloss Reinhardsbrunn (close to Gotha). That was where a Soviet trophy brigade seized the Danzig treasures in 1946; the van Goyen spent the next 10 years presumably hidden in the Hermitage.Footnote 14

Even if the name of Erich Koch should not be included in the painting’s pedigree of provenance, there is no question about the prominent name of Jacques Goudstikker, who purchased it in 1924 from the Dutch painter and dealer Dorus Hermsen (1871–1931) in The Hague. The 1923 expert listing of the painting by Cornelis Hofstede de Groot in his respected Catalogue raisonné of Jan van Goyen (1595/6–1656) gave the English title River Landscape with a Swineherd (Fluszlandschaft mit einem Schweinehirten in German), noting that it was signed and dated 1630; he provided two earlier provenance attributions from London in 1917 and 1919.Footnote 15 The Dutch RKD registration card gives the Dutch title as Landschap met hofstede (brug en varkens). Goudstikker exhibited the painting in Rotterdam in 1926 and 1927, using the French title Le Porcher (The Swineherd) in two of his catalogues (nos. 31 and 32), with images and a tracing of the date and signature as “VGoien 1638 [sic].”Footnote 16 Apparently, Goudstikker greatly admired the painting, and, reportedly, it was one of his prime examples in a lecture he prepared on paintings with representations of swine!Footnote 17

The painting appears as no. 1692 in Goudstikker’s small notebook known as the “Black Book,” which he had with him when he fled the Netherlands in May 1940.Footnote 18 No suggestion has been found that he sold that van Goyen before his death on 16 May 1940 aboard the ship that was carrying him and his family to safety across the English Channel.Footnote 19 That was just two days after Göring’s Luftwaffe bombed Rotterdam at the start of the Nazi occupation of the Netherlands.

THE VULTURES DESCEND: MURKY SHIFTS OF PROVENANCE, MAY 1940–DECEMBER 1941

Immediately after the German invasion, the vultures descended in search of major Dutch Jewish art collections with a sequence of under-the-table and backroom deals that are difficult to untangle, let alone fully comprehend, during the year and a half after Goudstikker’s death.Footnote 20 As key dates of importance, on 1 July 1940, Alois Miedl (1903–90), a German banker and businessman resident in the Netherlands, underhandedly acquired the entire Goudstikker legacy (against the wishes of the Dutch heirs), in what today would be considered a “forced sale,” purchasing the assets of the Goudstikker firm and rights to the J. Goudstikker name, against the wishes of Goudstikker’s widow. That acquisition was quickly countered on 13 July 1940 by Reichsmarschall Hermann Göring, who, in another highly questionable transaction, commandeered “all paintings … that were in the Netherlands on 26 June 1940 and that were the property of the said public limited company at that time.”Footnote 21

Subsequently, on 15 July 1940, many of the “Old Goudstikker” paintings were sold back to Miedl at a fraction of their value and, hence, under German occupation authorities, were considered part of the Goudstikker/Miedl inventory. The second in a series of lists for “Sales of Miedl to Göring during the period 1 July to 13 September 1940,” covering the “Oude N.V. Goudstikker” legacy, includes the painting under consideration: “1692 … J. v. Goyen Landsch.m.hofstede 100 x 93.5” (with a value of 1000 Reichsmarks); it appears on “Liste nr. 2: ‘Door Göring behouden van aankoop’ [Retention of purchase by Göring].”Footnote 22 This would affirm the painting was among those that passed to Göring ownership.

After Göring commandeered the Goudstikker Collection in a somewhat questionable arrangement with Miedl, most of the paintings were shipped to Berlin in July 1940. Many of them were delivered to Göring’s Carinhall estate, while others remained in Berlin with Göring’s principal art agent, Walter Andreas Hofer. Existing lists (including the copy cited above), leave no doubt that the van Goyen painting—at least in theory—passed to Göring, through Hofer. The Black Book no. “1692 J. v. Goyen Varkens” appears (with a value of 8,000 Reichsmarks) among the “Old Goudstikker” paintings Göring “purchased.”Footnote 23 There is no evidence, however, that the painting was actually delivered to Göring at Carinhall, which presumably explains why no “RM”—Reichsmarschall (RM) catalogue—number was assigned to it within the Göring Collection, as was the case of others actually acquired at Carinhall. That also explains why this van Goyen painting was not included in the original Göring catalogue of his collection, now held in the French Foreign Ministry Archives (AMAE) in La Courneuve.Footnote 24

Those dealings during the early years of German occupation still remain confusing, which may have affected the initial postwar 1953 settlement of the Dutch government with Goudstikker’s widow, whereby the Dutch government retained many of the paintings recovered after the war and returned to the Netherlands from the Göring Collection.Footnote 25 The fact that a large portion of the Goudstikker inventory remained with the Dutch government led to renewed legal proceedings in 1996–97 about the fairness of the Goudstikker postwar settlement. Indeed, it was not until 2006, after eight years of legal proceedings, that the Dutch government’s Advisory Committee on Restitutions finally agreed to the restitution of 202 paintings of Goudstikker provenance to his daughter-in-law Marei von Saher, a US citizen.Footnote 26

CORRECTING THE “CIR: GOERING COLLECTION”: GÖRING’S AUTUMN 1940 SALE TO KOCH

My initial allegation that Koch had purchased van Goyen’s River Landscape from Göring was based on its listing in the “CIR: Goering Collection.” The compiler, US Monuments, Fine Arts, and Archives art specialist, Theodore Rousseau, later chief curator at New York’s Metropolitan Museum, recorded a Göring sale “to Gauleiter KOCH, Danzig,” with four entries (with eight or more Dutch paintings). Rousseau’s quoted source was none other than Walter Andreas Hofer, Göring’s agent for the acquisition—or would-be “purchase”—of the entire Goudstikker inventory in July 1940. Under the heading “Sales of Objects Purchased on the Open Market,” the sale to Koch was one of several sales “to a group of friends” in the autumn of 1940, “immediately after arrival of the large shipment of works of art from Holland which included the Goudstikker Collection and pictures purchased from other Dutch dealers.” According to the “CIR: Goering Collection,” an oft-quoted source, although hastily prepared with little access to reference materials, the van Goyen was one of no fewer than 16 or 17 paintings from the Old Goudstikker Collection that Göring had sold to Koch—some in 1940 and others in 1943. Only the 1940 sale is in question here.Footnote 27

The fourth entry named in the “CIR: Goering Collection” was: “4. Jan van Goyen River Landscape bought from GOUDSTIKKER” (no Goudstikker number nor further details given).Footnote 28 Koch, the supposed recipient of all four entries named, who since 1928 was the NS Gauleiter of Königsberg, is incorrectly identified as Gauleiter of Danzig. As it turned out, the Danzig connection was quite appropriate since in fact, the painting actually was sold (although not by Göring) to the Nazi Gauleiter of Danzig, Albert Forster, by Miedl in December 1941!Footnote 29 Perhaps Hofer and/or Rousseau had simply gotten the Gauleiters mixed up, but, as it turns out, Koch did purchase the first set of four paintings on that sale list. The second and third paintings named in the same Göring sale to Koch, on the other hand, apparently never went to Koch or to Danzig, did not appear in the AMAE Göring catalogue, and were never assigned Göring “RM” catalogue numbers.

The first entry on that “CIR: Goering Collection” list that can be verified as being acquired by Koch—was Canaletto’s Four Views of Venice—“all purchased from GOUDSTIKKER and numbered 2165, 2166, 2167, 2168 in the original catalogue.”Footnote 30 According to the original AMAE Göring catalogue, these Four Views of Venice were initially hung in Carinhall—“two in the entrance hall (RM324 and RM325, acquired 28 July 1940) and two in a reception room (RM370 and RM371, acquired June 1940).” All are noted there as being “returned to Hofer”; in fact, they went to Koch in Königsberg and never went to Danzig.Footnote 31 All four can be matched with the 1945 list of Koch’s Weimar deposit from Königsberg; two of them (matched with a later 1947 Weimar list of remaining Koch paintings and also with Hermitage documents) are reportedly now in the Hermitage, although now attributed to the School of Canaletto rather than to Canaletto himself.Footnote 32

This would explain why Nancy Yeide, author of the authoritative 2009 catalogue raisonné of the Göring Collection, has no entry for the Goudstikker van Goyen now in Gdańsk in her “Section A” for paintings that she had confirmed were acquired by Göring, whereas she does include the van Goyen in her “Section B—Likely in Göring’s Collection”:

B88, Jan Van Goyen (1596–1656), Landscape with Farm, 1638, Oil on canvas, 100 x 93.5 cm. Goudstikker 1692, … Doros Hermson (The Hague); (Goudstikker, Amsterdam); acquired July 1940 by Göring;3 …

3 … This could be the picture of the same dimensions that was together with Doros Hermson and then Goudstikker, listed in Hans-Ulrich Beck, Jan van Goyen, Amsterdam, 1973 (II: no. 160) and now at the museum in Danzig (No. M/428/MPG).Footnote 33

Confirming Yeide’s citation, already in 1973, Hans-Ulrich Beck’s catalogue raisonné, Jan van Goyen, describes (with an image) the van Goyen painting now in Gdańsk with the title A Swineherder Drives Three Pigs (Ein Schweinehirt treibt drei Schweine). Curiously, however, neither the name Göring nor Koch appear in Beck’s provenance notes. Following the provenance listing for the Dutch dealer Dorus Hermson in The Hague, from whom Goudstikker purchased the painting in 1924, and Goudstikker (in Amsterdam), he does not mention the Göring acquisition, nor does he mention the name of Miedl. He next cites an unidentified Berlin auction on 3 December 1940 with sale to the Danzig Museum (for 47,000 Reichsmarks).Footnote 34 Apparently he was not aware that the painting reverted to Miedl after the Hans W. Lange auction in Berlin on 3 December 1940.

As yet another confusing twist, in her Göring catalogue, Yeide lists in “Section C—Uncertain Associations” a second entry for the same Gdańsk van Goyen (with the same title as in the “CIR: Goering Collection”):

C29 Jan van Goyen (1596–1656) River Landscape … (Goudstikker/Miedl, Amsterdam); acquired by Goering; sold for 130,000, with RM 324, RM 325, RM 370, RM 371 and two other pictures to Gauleiter Koch, Danzig.Footnote 35

Here again, the only Göring “RM” numbers that Yeide gives in this alleged Göring sale to Koch are for the same four Canaletto Four Views of Venice (listed with Goudstikker numbers as in the “CIR: Goering Collection”), which we already now know Göring did sell to Koch. The Göring Database on the website of the German Historical Museum follows the Bundesarchiv Koblenz’s (postwar) copy of the Göring catalogue (noting the “CIR: Goering Collection”) about the sale to Koch, although with a parenthetical correction to the Danzig Gauleiter Albert Forster:

RMG00721: Jan van Goyen Landschaft mit Bauerngut (Goudstikker no. 1692) [with dimensions of] 100 x 93.5 [cm]; [with the date of] 13 July 1940 for receipt by Göring’s agent Walter Andreas Hofer; [and] a sale to Gauleiter Koch (Forster, Albert), Danzig Stadtmuseum; now in Poland.Footnote 36

SOLD ON AUCTION (BERLIN, 3 DECEMBER 1940) BUT RETURNED TO MIEDL (AMSTERDAM)

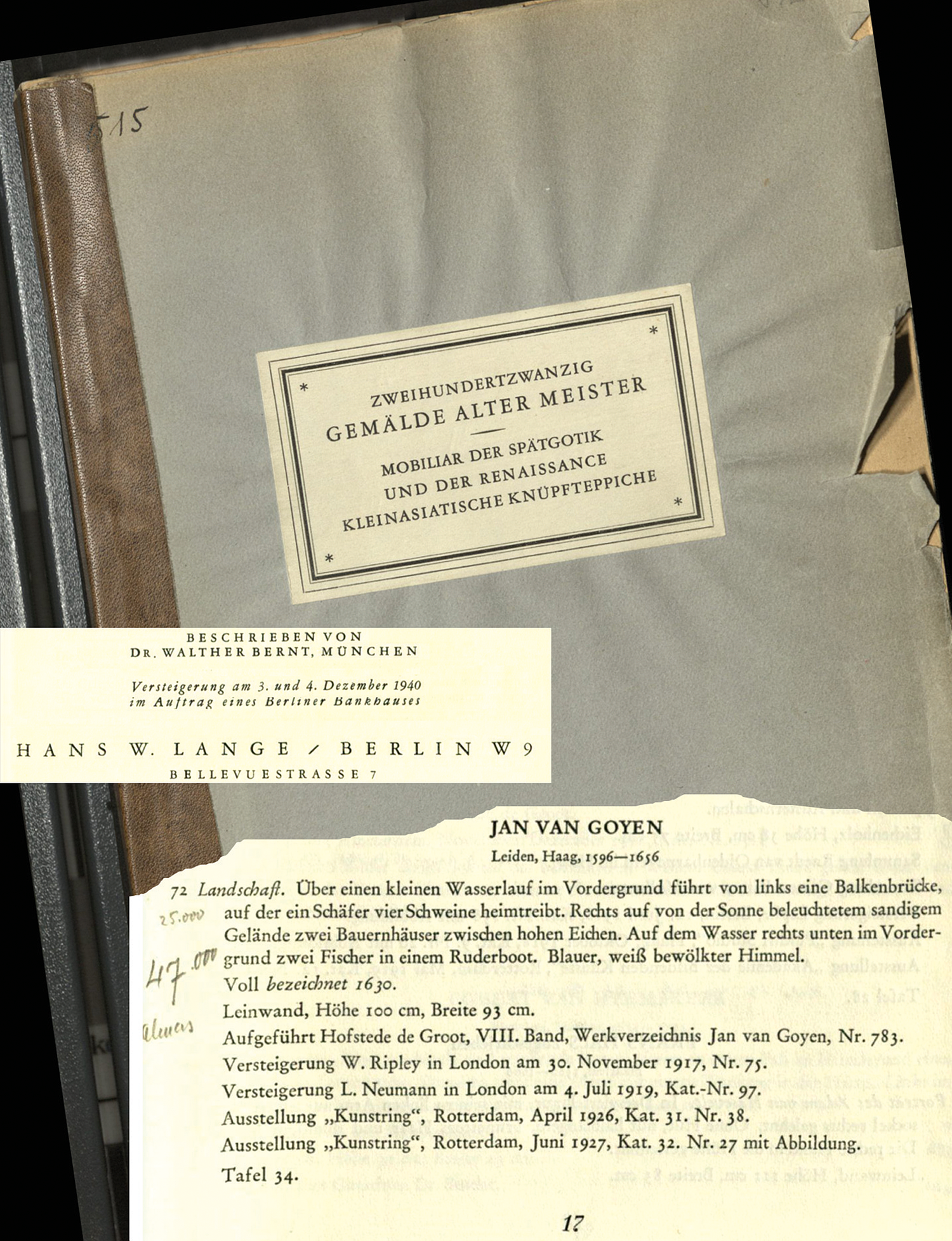

The inclusion of Erich Koch in any provenance history for the van Goyen must accordingly be discarded as erroneous; this allegation is definitely contradicted by the documented sale of the painting at auction on 3 December 1940 in Berlin, where there is no indication—or other suggestion—that Koch was in any way involved. The auction catalogue for Hans W. Lange’s large Berlin sale on 3–4 December 1940 of predominantly Goudstikker paintings was compiled by German art expert and collector Walther Bernt (1900–1980), who was based in Munich. Bernt’s personally annotated copy of the auction catalogue, part of his large collection gifted to the Fine Arts Library of Harvard University, lists the van Goyen (Lot no. 72) with a full-page image (Plate no. 34) (see Figures 3 and 4).Footnote 37

Figure 3. Hans W. Lange Auction, Berlin, Catalogue for Sale, 3–4 December 1940, compiled by Walther Bernt, Lot no. 72: JAN VAN GOYEN, Landschaft (Landscape). The presale estimate of 25,000 Reichsmarks, the sale price of 47,000 Reichsmarks, and the purchaser [Maria] Almas[-Dietrich] penciled in the left-hand margin by the compiler of the catalogue (reprinted from the personal copy of Walther Bernt, donated with his collection to the Fine Arts Library, Harvard University).

Figure 4. Plate 34: 72 JAN VAN GOYEN, Lange Auction Catalogue, 3–4 December 1940. The sale price of 47,000 Reichsmarks penciled below by the compiler (reprinted from the personal copy of Walther Bernt, donated with his collection to the Fine Arts Library, Harvard University).

Bernt’s preface claims the works of art were from private collections, but (as appropriate in 1940 Berlin) Goudstikker is not named nor is Göring. The sale, allegedly engineered by Miedl in cooperation of Hofer and associates, was announced in Bernt’s catalogue as being “on commission from a Berlin bank,” which, given the offerings of Goudstikker provenance (not so indicated), might suggest the involvement of the Landvolkbank in Berlin, of which Miedl was a half owner. While no provenance notes in the catalogue mention the name of Goudstikker or any other current owner, a review of the many items with corresponding Goudstikker “Black Book” numbers suggests a major consignment of Oude Goudstikker paintings were being offered for sale—namely, those not appropriated by Göring. In the case of the van Goyen, even the provenance notes given for the Rotterdam exhibitions in 1926 and 1927, for which the painting was pictured in the Goudstikker catalogues, do not mention the name of Goudstikker for those years.Footnote 38 Yet, quite appropriately, the name “[J. Goudstikker]” appears (written by hand) on both the cover and the title page of another annotated copy of that Lange sale catalogue held by the RKD in The Hague.Footnote 39

On a loose printed sheet with estimated (anticipated) sale prices, the van Goyen is listed at 25,000 Reichsmarks. Bernt’s personal annotated copy of the sale catalogue has that estimated price penciled in the margin beside the van Goyen entry, along with the sale price of 47,000 Reichsmarks (exactly the sale figure quoted by Beck in 1963, discussed earlier). However, Bernt noted “Almas” as the buyer in the margin beside Lot no. 72—namely Maria Almas-Dietrich, one of the principal buyers for Hitler’s Linz Museum, who Bernt noted in pencil also purchased at least four other paintings in the sale.Footnote 40 The published compendium of auction prices gives a sale price of 42,000 Reichsmarks for Lot no. 72 (van Goyen), a difference of 5,000 Reichsmarks from the price noted by Bernt (quite probably the commission).Footnote 41

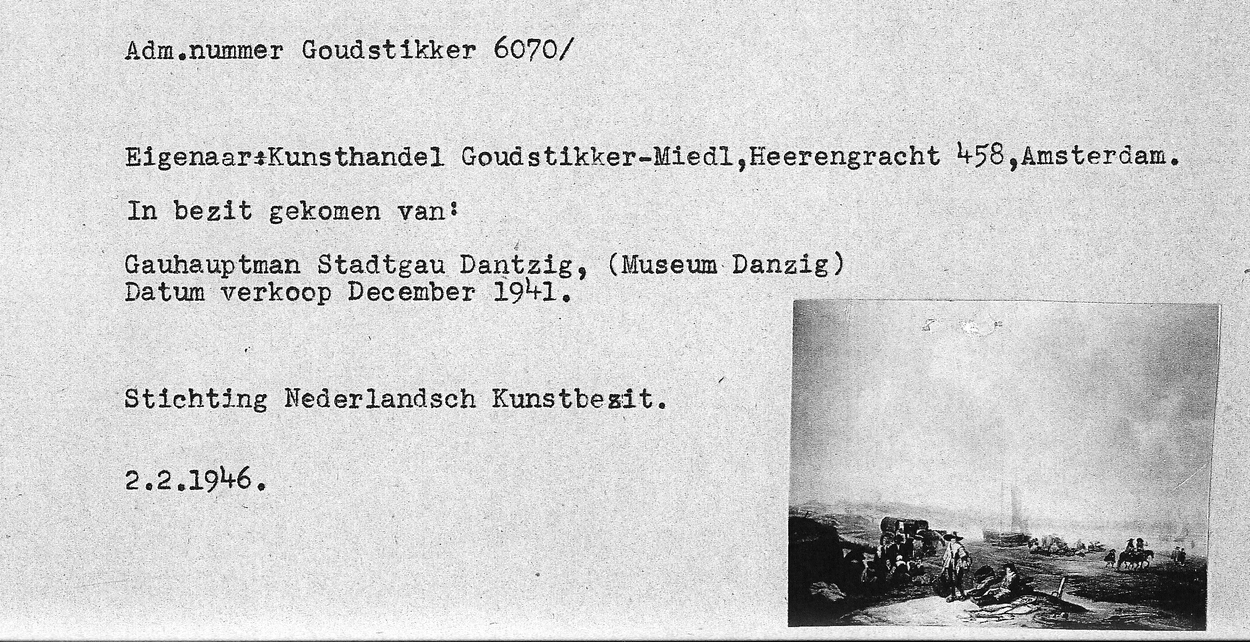

If the van Goyen went to the Almas Gallery in Munich, it did not stay there long, and it was not chosen for the Linz Museum. The RKD (Miedl) card for that van Goyen confirms that on 15 July 1941 the painting returned to Miedl in Amsterdam at the prestigious Goudstikker Gallery that he had taken over on the Herengracht.Footnote 42 Although none of the “purchasers” penciled in the margin of Bernt’s annotated catalogue mention the name of Miedl, a 14 July 1941 covering note remains from the Berlin freight forwarder Schantung Handels-Aktiengesellschaft for paintings, tapestries, and various sculptures shipped to Miedl at Herengracht 458. These documents, including the list of paintings shipped, are publicly available among the wartime files of the Miedl-Goudstikker Amsterdam firm within the records of the postwar Netherlands Management Institute (Nederlandse Beheersinstituut [NBI]) in the National Archives in The Hague. The Miedl files from the postwar investigation of the wartime art market also have a summary tally of the results of the Lange sale and related documents.Footnote 43 Further clarification is needed, however, to understand how and why so many of the paintings that were supposedly “sold” at the Lange Auction in Berlin were returned to Miedl at the Goudstikker Gallery on the Herengracht. Nevertheless, these documents confirm Miedl’s acquisition of many of the paintings that Göring did not keep from the Goudstikker Collection, including the van Goyen.

Such details in the transactions between Goudstikker’s death in May 1940 and Miedl’s now-confirmed sale of the van Goyen to the Danzig Museum in December 1941 are still inadequately explained and arouse suspicions, particularly the Berlin auction and the transfers back and forth to Miedl. Given the complexity of the legal issues involved, it is not my intention to enter the judicial fray. However, even if Göring did not sell the painting to Koch, it does not lessen its “red-flag” status as a victim of Göring and Miedl’s hasty underhanded acquisition in what many today would consider a “forced sale,” if not an illegal wartime seizure, from the estate of a Holocaust victim within two months of his unfortunate death aboard the ship carrying him and his family to safety from the Nazi invaders.

SALE TO GAULEITER FORSTER, DANZIG, DECEMBER 1941

The postwar 1946 SNK loss-registration form for van Goyen’s Landschap met hofstede, brug en varkens (Landscape with Peasant Farm, Bridge and Swine) (Goudstikker no. 1692) in the SNK files in The Hague lists Göring’s acquisition (1 July–13 September 1940) followed by the sale to Danzig in December 1941. The Lange December 1940 auction is not mentioned, although, clearly, the various copies of the Lange catalogue, and reports of the sale, including annotated sales and published lists of sale prices, all indicate that the painting was sold on that Berlin auction. Kunsthandel Goudstikker/Miedl in Amsterdam is noted as the last owner on the SNK form (Figure 10).Footnote 44 The sale to the Danzig Museum (Stadtmuseum) dated December 1941 was a year after the Lange Berlin auction and over a year after the Hofer-alleged sale of the van Goyen to Koch (in Danzig), as erroneously listed in the “CIR: Goering Collection.”

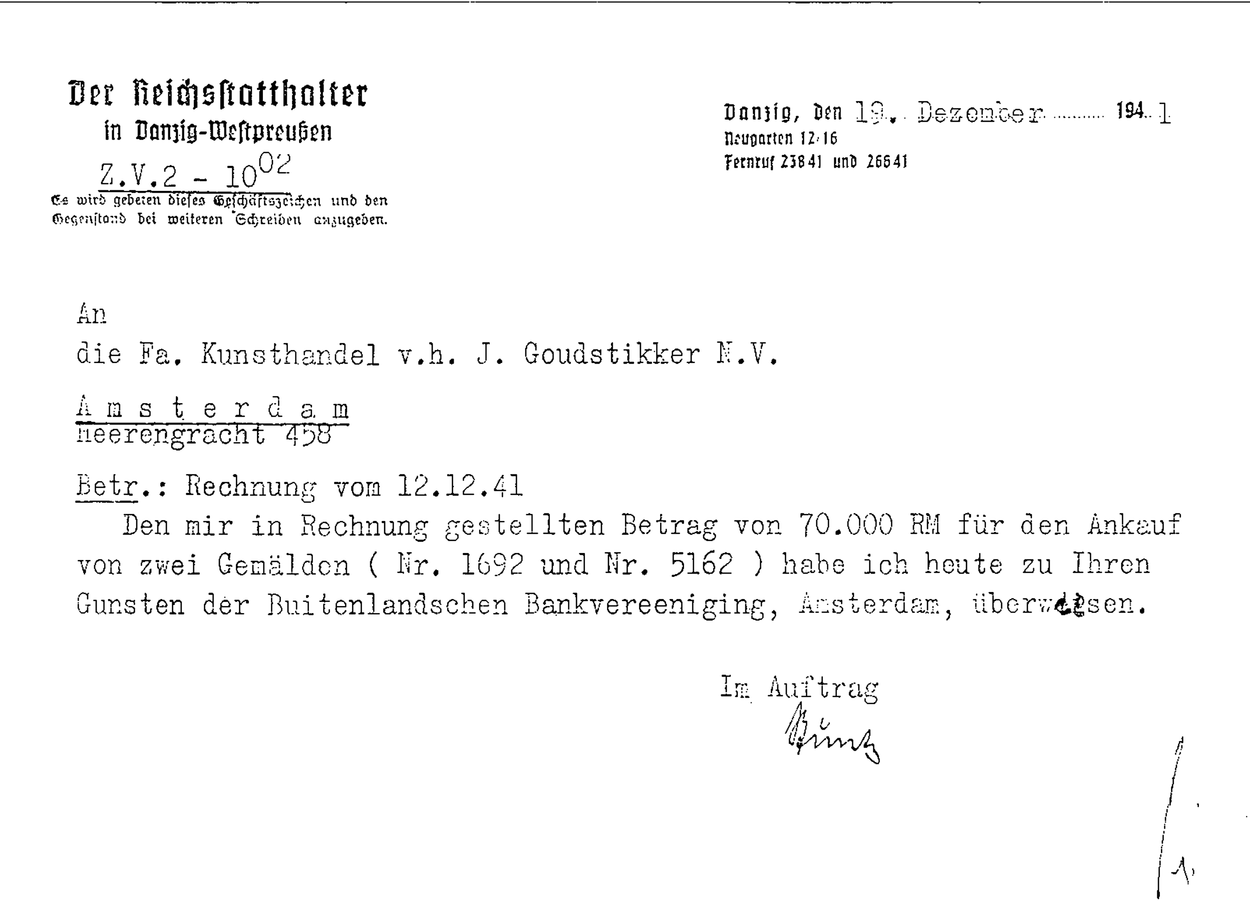

On 19 December 1941, Gauleiter Albert Forster, on the letterhead of his office of Reichsstatthalter in Danzig-West Prussia, addressed a notice of payment through a foreign bank to Kunsthandel v.h. J. Goudstikker N.V., Amsterdam, referencing an invoice of 12 December 1941 for the purchase of two paintings—“Nr 1692 and Nr 5162”—and naming the sum of 70,000 Reichsmarks (Figure 5). No. 1692 obviously was the van Goyen! The original incoming archival copy of this document has not yet been located.Footnote 45

Figure 5. Signed note from Albert Forster, Gauleiter and Reichsstattthalter of Danzig-West Prussia, confirming payment to Kunsthandel v.h. J. Goudstikker (Miedl) for two paintings (No. 1692 and No. 5162) (courtesy of Nina Senger, Christie’s, Berlin).

Along with the Goudstikker van Goyen (no. 1692), the second Miedl no. 5162 turns out to be a painting then attributed to Pieter de Hooch (1629–84; sometimes referred to as de Hoogh), Bei der Wahrsagerin (At the Fortuneteller), of provenance in the collection of Nathan Katz in Dieren (see Figure 6). The painting was another Miedl “red-flag” purchase on 6 August 1940, along with some 500 paintings he acquired from the Katz brothers.Footnote 46

Figure 6. Anonymous, The Fortune Teller (earlier attributed to Pieter de Hooch), from the collection of Nathan Katz, Dieren (The Netherlands), now in the Muzeum Narodowe, Gdansk. Sold by Miedl to Gauhauptman Reichgau Danzig Albert Forster for the Stadtmuseum, Danzig, 12 December 1941 with the van Goyen (courtesy of Muzeum Narodowe, Gdansk).

Some confusion might arise about that The Fortune Teller from the Katz Collection because another de Hoogh painting of a Fortune Teller appears next to the van Goyen on the list (cited above) of “Oude Goudsikker” paintings that Göring retained in the summer of 1940: “1693 P. de Hoogh [sic.] Waarzegster (96.3 cm x 129 cm … [price 22,000]).”Footnote 47 This larger de Hoogh painting owned by Goudsikker (with those dimensions) also appears in the Goudstikker Black Book (no. 1693), coincidentally, one number after the van Goyen.Footnote 48 The Fortune Teller that Miedl sold to Danzig from the Katz Collection, however, has dimensions that are half this size (50.2 x 45 centimeters), as confirmed (with image) in the 1943 Drost catalogue of recent purchases for the Danzig City Museum, which he directed under NS occupation.Footnote 49

The postwar SNK “missing from the Netherlands” registration document further confirms the D. Katz (Dieren) provenance of the de Hooch painting sold to Danzig. This document indicates its transfer to Goudstikker/Miedl in Amsterdam on 6 August 1940 and then sale to the Danzig Museum on 12 December 1941.Footnote 50 That same de Hooch(?) Fortune Teller from the Katz Collection sold to Danzig also appears on a list of the Dutch paintings that the Dutch government officially claimed after the war, as submitted to US occupation authorities in Germany.Footnote 51 The curator of the Muzeum Narodowe in Gdańsk in charge of early Dutch and Flemish art, Beata Purc-Stępniak, recently verified that this painting is now registered under Pieter de Hooch (1629–83) (Hoogh?) because there is a signature of “Pie. D. Hooch” in the lower left corner. However, she further explains: “[S]uch attribution cannot be maintained. By no means is this painting by de Hooch.”Footnote 52 Indeed, currently, the RKD in The Hague no longer attributes Katz’s The Fortuneteller (49.5 x 44.5 centimeters) to de Hooch but, rather, cites an anonymous seventeenth-century artist from the northern Netherlands (1635–60). The RKD cites Peter C. Sutton’s Reference Sutton1980 catalogue raisonné Pieter de Hooch, in connection with the rejected de Hooch attribution; Sutton in turn notes for The Gipsy Fortune-Teller: “Old photographs reveal that the signature has been falsified.”Footnote 53 The RKD’s English title is Gipsy Telling a Young Woman’s Fortune outside a Shed, with provenance of D. Katz of Dieren (Rheden) and the present location is Muzeum Narodowe in Gdańsk.Footnote 54

Among the Miedl-Goudstikker business records during wartime German occupation (now held among the NBI records in the Dutch National Archives), remaining Miedl accounting registers confirm Miedl’s sale of those two paintings in December 1941 to the Reichsstatthalter Danzig-Westpreussen, Albert Forster, for the Danzig City Museum. A separate stock register of Miedl’s Oude Goudstikker holdings (below no. 5000) has not been located—that would have specifically recorded the sale of the van Goyen (Oude Goudstikker no. 1692) to Forster on 12 December 1941.Footnote 55 However, Miedl’s stock register of paintings with running numbers starting with 5001 (that is, above the Oude Goudstikker numbers) lists the de Hoogh Fortuneteller (Miedl no. 5162) as being acquired from Katz on 6 August 1940 for 3,000 guilders. The corresponding facing page for outgoing transactions confirms its sale to the Stadtmuseum Danzig on 12 December 1941 for 15,071.59 guilders. These same data are repeated on the SNK’s 1946 “missing” registration form (Claim no. 5813).Footnote 56

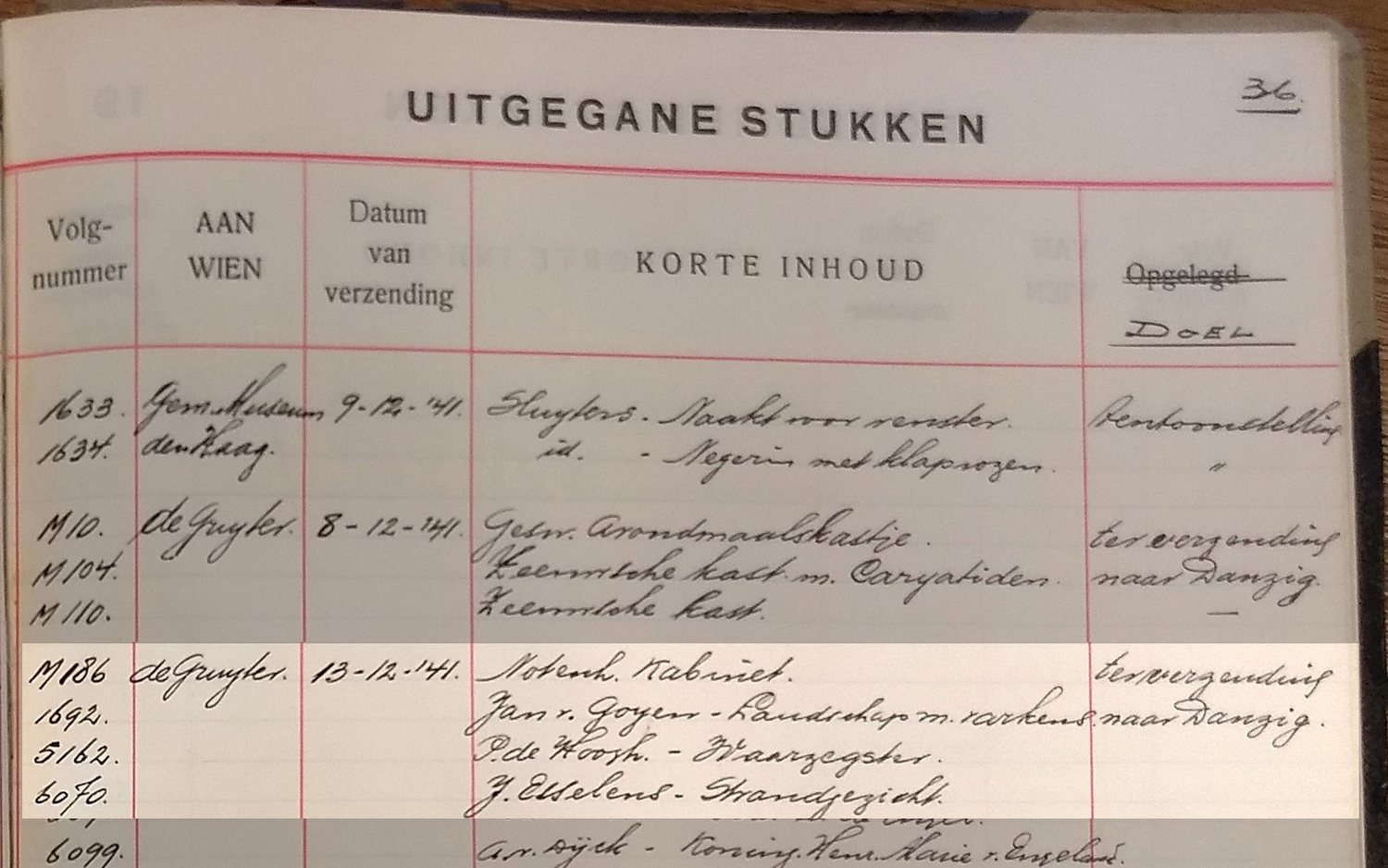

Miedl’s 12 December 1941 sale of those two paintings to Danzig—van Goyen (no. 1692) and Pieter de Hoogh (no. 5162)—is also recorded in the Goudstikker-Miedl firm’s chronological register including receipts (Ingekomen stukken) and outgoing items (Uitgegane stukken). There, we learn that a third Dutch painting by Jacob Esselens, Strandgezicht (Beach Scene) (Miedl no. 6070) was also included in the same December 1941 sale to Danzig (see Figure 7), although no price is indicated.Footnote 57 The Esselens painting was not mentioned in Forster’s 19 December 1941 payment notification to Miedl mentioned above (Figure 5), but, as noted below, the Danzig Muzeum registration (March 1942) confirms its arrival.Footnote 58

Figure 7. Cropped clipping from Miedl transaction register, 13 December 1941, NBI 861, folio 36 (reprinted from the Dutch National Archives; courtesy of Bureau Herkomst Gezocht, The Hague).

Checking in the register of Miedl holdings above no. 5000 (in which the sale of the Fortune Teller to Forster was also recorded), we learn that Miedl had purchased the Esselens painting (Miedl no. 6070) at the Muller auction on 17 October 1941 (no price given), which he in turn sold on 12 December 1941 to “Gauhauptmann Reichgau Danzig [that is, Albert Forster]” for 9,042.95 guilders.Footnote 59 The Frederik Muller auction catalogue for the 17 October 1941 sale in Amsterdam indeed lists the painting Strandgezicht (Beach Scene), signed by Jacob Esselens (1626–87), as Lot no. 304 (oil on canvas, 84 x 108 centimeters), but provides no consignor or earlier provenance notes.Footnote 60 These data likewise appear on the SNK’s 1946 “missing” registration form for the Esselens painting.Footnote 61 A typewritten copy of that SNK registration form for the Esselens painting found in another SNK file includes a thumbnail image (Figure 8). This same SNK file contains a 1946 list of 29 paintings and other works of art sold to Danzig during the German occupation, prepared in connection with postwar Dutch claims, as will be discussed below. All three paintings that Miedl sold to Forster on 12 December 1941 appear on this list with similar data as given above.Footnote 62

Figure 8. Bottom portion of a page with typewritten data from the SNK’s “missing” form (no. 6072) for the Esselens painting (Goudstikker-Miedl no. 6070), NA SNK 327 (reprinted from the National Archives; courtesy of Herkomst Gezocht, The Hague).

VISIT TO GDAŃSK AND THE VAN GOYEN

When Polish colleagues in Gdańsk heard of my efforts to track down the Koch Collection and my earlier supposition (and theirs) that some of the paintings that Göring had sold to Koch might still be in Gdańsk, they kindly arranged a visit for me in July 2014. From what they were able to ascertain in advance, after I sent them an initial list of the paintings Koch had reportedly purchased from Göring (as per the “CIR: Goering Collection”), they informed me that only the van Goyen was now in Gdańsk. At that point, I had not known any details about the 12 December 1941 sale explained above, and, hence, neither the de Hooch(?) or the Esselens were on my agenda. My Gdańsk colleagues had warned me, even before I booked the trip, that the director of the National Museum (Muzeum Narodowe), Wojciech Bronisławski, had publicly denied that the van Goyen had come from the Goudstikker Collection or from Göring. They sent me a clipping from the local newspaper Dziennik Bałtycki (with an image of the painting) quoting Bronisławski’s response to a journalist’s inquiry, insisting that there were no Goudstikker or Göring connections. He had explained that the van Goyen “was purchased during the war on the Dutch art market by Albert Forster,” naming a purchase price of 50,000 Reichsmarks.Footnote 63 An earlier 2007 article on “trophy art” in Der Spiegel pictured that same Goudstikker van Goyen held in Gdańsk; also pictured there in color was another Goudstikker Dutch seventeenth-century painting now in Gdańsk by Willem van Nieulandt, Italienische Landschaft, which the Danzig Museum purchased from Miedl in March 1944 (following an elaborate trade with Göring).Footnote 64 There were enough questions demanding clarification to justify the trip, especially with those early reports suggesting that perhaps the director was not fully informed about the provenance of the museum collections or else was not prepared to reveal the whole story.

My 2014 visit to the Muzeum Narodowe in Gdańsk included a lengthy meeting with Director Wojciech Bronisławski, the deputy director, and, as mentioned earlier, the curator responsible for Dutch and Flemish paintings, Beata Purc-Stępniak, who had kindly prepared considerable documentation for me on the van Goyen. They explained that they had no documentation about the purchase of the van Goyen by Gauleiter Albert Forster for the museum (many records did not survive the war). They quoted a 1942 newspaper account that announced the van Goyen acquisition at the end of 1941 or early 1942. However, they could provide no further provenance data before the painting was “purchased on the Dutch art market for the museum by Albert Forster.” Bronisławski again named the price as 50,000 Reichsmarks.

Even more important, the curator furnished me with a copy of a page from the wartime Danzig museum register showing the van Goyen was entered in March 1942 (Stm. 479). At the time of my visit, I had not known about the Fortune Teller and the Esselens that Forster had purchased together with the van Goyen from Miedl, but their acquisition is likewise confirmed on the same page of the museum register; the de Hooch painting (Stm. 478) immediately precedes the van Goyen, and the Esselens is entered several lines down (Kgm. 4632).Footnote 65 They also showed me the 1943 published catalogue of “New Acquisitions 1940/41” (mentioned above), prepared by Danzig City Museum Nazi wartime director, German art historian Willi Drost. Both the van Goyen and the de Hooch are pictured, along with others purchased 1940 and 1941, including at least nine of them from dealers in the Netherlands, as since confirmed in SNK documentation. The Esselens, however, is not included.Footnote 66 This NS wartime publication itself, however, provides no earlier provenance or acquisition data for any of the paintings that Drost discussed or those pictured.

Curator Purc-Stępniak came to the meeting with documentation and a compact disc prepared for me, which she eagerly demonstrated, even before they escorted me to the gallery. When she showed me the images, including details of the verso of the van Goyen painting, I was fully reassured about the importance of my visit: I could immediately point out to her the familiar Goudstikker label in the center of the stretcher! What a coincidence, I explained, as the no. 1692 inscribed thereon corresponds precisely to the number I had noted from the Goudstikker “Black Book” catalogue and other Dutch sources for the van Goyen.Footnote 67 I then showed them my copy of the SNK’s loss registration form from The Hague, which also confirmed the Goudstikker provenance and that same number for the van Goyen.

WARTIME EVACUATION AND SOVIET SEIZURE

The Gdańsk museum also kindly gave me photocopies of their relevant wartime evacuation lists, which indeed included the van Goyen. Along with many other important paintings from Danzig, including many of those purchased by Forster and Drost, the van Goyen was first evacuated on 13 July 1942 to Senslau (now Polish Żelisławki, not far from Danzig) and then, on 2 August 1944, to Schloss Reinhardsbrunn near Gotha (close to Weimar) in Thuringia.Footnote 68 They told me that a Soviet trophy brigade had seized the van Goyen and other Danzig paintings from Schloss Reinhardsbrunn and transported them to the Hermitage. Hans Memling’s Triptych of the Last Judgement, Danzig’s most famous painting from Saint Anne’s Church, was among the Soviet seizures. The de Hooch painting purchased with the van Goyen is likewise listed on the same wartime evacuation lists and was among the Soviet seizures. That seizure is well confirmed by other sources, although the relevant Soviet documentation is currently reclassified in Russia.

In contrast to these two paintings, the Esselens was reportedly evacuated in July 1942 to the village of Russoschin (Rusocin in Polish), 16 kilometers south of Danzig. One wartime listing in the Danzig Museum files includes the Esselens among “Paintings of the Gauleiter” (no. 4632).Footnote 69 While it was not listed with those other Danzig paintings evacuated to Gotha (Thuringia) in 1944, its subsequent fate is unknown. In any case, it did not return to Gdańsk, and is most recently pictured in the 2017 catalogue among 405 paintings lost during the war by the Stadtmuseum Danzig. That catalogue notes its provenance as “Purchased in wartime in the Amsterdam art market” and also a more specific reference that it was “purchased ‘Goudstikker Amsterdam’” as well as a note that it is “signed in the lower right corner” (see Figure 9).Footnote 70

Figure 9. Jacob Esselens (1626–87), Strandgezicht (Beach Scene). Sold by Miedl to Gauhauptmann Reichgau Danzig Albert Forster, 12 December 1941. Polish title: Brzeg morza (Danzig registration: Kgm. 4632), not returned from wartime evacuation (current location unknown) (reprinted from Helena Kowalska, Straty wojenne Muzeum Miejskiego (Stadtmuseum) w Gdańsku, Seria Nowa, vol. 1 [Gdańsk: Muzeum Narodowe w Gdańsku, 2017], 131).

Both the van Goyen and the painting then still attributed to Pieter de Hooch, along with the Memling and a number of other paintings from Gdańsk, were pictured in the extensive 1949–50 published Catalogue of Paintings Removed from Poland by the German Occupation Authorities, prepared by the Polish Ministry of Culture (also in English for international circulation). The introduction claims the Danzig Stadtmuseum collections were taken to the Hamburg area, but says nothing about the 1944 evacuation of Memling’s Triptych, the van Goyen and others to Thuringia, or the 1946 seizure by a Soviet “Trophy Brigade” in the Soviet Occupation Zone of Germany.Footnote 71 Meanwhile, Danzig and its surrounding region became part of Poland in August 1945. When that catalogue was issued (first in Polish in 1949), Poland was firmly in the Soviet orbit, and, at that point, those paintings were in Leningrad. The catalogue gave no provenance data for the van Goyen or the other Danzig paintings that Forster and Drost had also “purchased on the Dutch art market” during the war.

SNK WARTIME “MISSING” REGISTRATION AND DUTCH POSTWAR CLAIMS

Meanwhile in the Netherlands, following liberation, Dutch specialists immediately started registering war losses in an effort to retrieve Dutch art and other cultural valuables of the royal family and government institutions as well as private organizations, families, and individuals. The SNK organized one of the most thorough item-level art registration systems of any victimized country for individual wartime art losses, seized or sold, and taken abroad during the NS occupation.Footnote 72 Item-level forms were collected reflecting the extensive Dutch losses through German seizure as well as foreign sales through the active Dutch art market, involving a number of ‘Aryanized’ dealers.

Danzig provides a key highly revealing example, which is apparent from a recent initial search of the paintings pictured in Drost’s Reference Drost1943 catalogue of the Danzig museum new acquisitions. Many of those that Drost pictured, along with others sold to Danzig during wartime occupation, now appear in the Herkomst Gezocht database in The Hague, which incorporates copies of those Dutch SNK registration forms. Copies of postwar report forms for many of the paintings sold to Danzig could easily be found, thereby determining the seller for those purchased on the wartime art market and “removed from the Netherlands during German occupation.” Most of those sales by NS-approved (that is, Aryanized) dealers operating during the occupation doubtless involved what today would be considered “red-flag” sales, but further provenance research will be required in each case. The SNK’s “missing” form for the van Goyen in question (see Figure 10) is a good example, where provenance prior to the sale to Danzig is provided, because 80 years after Danzig was invaded and annexed to the Third Reich, that painting sold in December 1941 is still “missing from the Netherlands.” And even though it has hung in the Municipal or Regional—and, since 1972, National—Museum in Gdańsk for the last 50 years, its real provenance has never been openly revealed.

Figure 10. 1946 SNK “missing” registration form for the Goudstikker van Goyen (Oude Goudstikker no. 1692), Claim no. 5779, SNK 2.08.42/751/9274, 26 January 1946 [note 44 above] (reprinted from the National Archives, The Hague; courtesy Herkomst Gezocht, The Hague).

Symbolically in Amsterdam, the SNK office occupied the premises of the former Goudstikker (and wartime Miedl) Gallery on the Herengracht. Already in 1946–47, given the large quantity of Dutch-owned art revealed in the SNK’s registration forms that were sold during occupation to Nazi leaders or museum directors, or dealers, in the cities of Danzig, Breslau, and Posen, all annexed to the German Reich, but that became part of postwar Poland, the SNK staff prepared a compilation listing some 75 works of art sold to those three major Germanized cities.Footnote 73 Our focus on the Goudstikker van Goyen can be seen in the context of 26 paintings (plus a watercolor, a drawing, and a tapestry) “sold” to Nazi authorities in Danzig on the SNK combined list of sales to Poland, all purchased for the Danzig museum, either personally by Nazi Gauleiter and Reichsstattthalter of Danzig-West Prussia Albert Forster or by Nazi German museum director Willi Drost. Of the two-page Danzig list (see Figure 11), half of the paintings—the initial 12 paintings listed—were sold by Miedl’s firm of Goudstikker-Miedl; included are the two other paintings Albert Forster purchased at the same time as the van Goyen—namely, de Hooch(?)’s Fortune Teller and Esselens’s View on the Beach. Footnote 74

Figure 11. “Liste de tableaux, vendus à Danzig,” SNK 2.08.42, inv no. 327, National Archives, The Hague. Danzig portion of a 1946–47 SNK List entitled “Documentation Regarding the Search in Poland and Recuperation of Cultural Assets Lost in the Netherlands,” with data on wartime sales to cities that became part of Poland after the war (courtesy of Herkomst Gezocht, The Hague).

Similar lists as part of the same SNK document cover 25 paintings sold to a dealer in Posen (now Polish Poznań), which had been annexed to the Third Reich in 1939 as the capital of Reichsgau Wartheland, where the Wielkopolskie (Greater Poland) Museum had become a branch of the Kaiser-Friedrich Museum in Berlin, as well as nine paintings and additional antique furniture and porcelain sold to Breslau (now Polish Wrocław), where the museum in that prewar German-dominated major city of Silesia was directed by Gustav Barthel, one of Kajetan Mühlmann’s main assistants.Footnote 75 (Several additional paintings listed were sold to Hans Haid in Bischdorf, near Liegnitz [now Polish Legnica], which became the Soviet military headquarters after the war.) These three major cities were annexed to the Third Reich, and all had major museums during the war, and, as with the Danzig example, their Nazi-elite leaders and museum directors had generous financial allocations to enrich their museum holdings with Nazi-approved art. With Dutch and Flemish Old Masters among the most sought-after paintings in Nazi artistic taste, there was plenty of quality on the Dutch art market.

Most of those sales or transfers out of the occupied Netherlands initially came from German seizures and forced sales from wealthy Jewish collectors and art dealers obliged to flee their home countries, whose galleries were Aryanized during the NS rule. The holdings of those Germanized firms, such as the case of the Miedl takeover of the Goudstikker firm, greatly expanded during the war. Further research on these issues and particularly specific cases will be needed to determine which items sold to those cities now in Poland may have been the property of victimized Dutch Jews who fled the country or were deported. For the Netherlands, special attention is needed on items previously owned by those Jews forced to deposit their art and other valuables with the so-called “robber bank” Lippmann, Rosenthal and Company. Notably, the Lippmann-Rosenthal name appears as an earlier source for many works of art on the SNK wartime Polish sale lists, especially for items sold to a dealer in Posen.Footnote 76

As evident from other documents in the same SNK file, Dutch diplomatic officials in 1946 and 1947 were in direct contact with their relevant Polish counterparts, who were anxious to recover Polish property seized during the war. By then, however, the new Polish government had already enacted a decree in 1946 forbidding the export of cultural items recovered within the territories of postwar Poland.Footnote 77 That would have made repatriation to the Netherlands extremely difficult, if not virtually illegal, even if the van Goyen and other paintings had been returned to Gdańsk immediately after the war. As far as is known, that decree is still in effect today. Most probably in 1946, neither Dutch nor Polish diplomats or other officials knew the fate of those paintings from Danzig in Schloss Reinhardsbrunn (near Gotha) that had fallen prey to a Soviet trophy brigade. That would also explain the lack of success for Dutch postwar retrieval efforts.Footnote 78 Claims filed with Western Allied restitution authorities in occupied Germany for those Dutch-owned paintings sold to Danzig were likewise in vain.Footnote 79

RETURN FROM LENINGRAD: GDAŃSK AND EXHIBITION TOURS

A 2014 publication of selected documents from the Hermitage Archive related to postwar “displaced” or “trophy art” in the Leningrad Museum from 1945 to 1955 provided limited insights before the volume was withdrawn from circulation three years later. The frontispiece of a small section with only limited documents relating to art removed from Poland, featured Hans Memling’s Triptych of the Last Judgement, the most famous Soviet-seized painting from Gdańsk, pictured on exhibit in the Hermitage.Footnote 80 Other paintings, including the Goudstikker van Goyen, that had accompanied the Memling from Gotha to Leningrad, were not mentioned. Apparently, Hermitage specialists had taken no notice of the Goudstikker label on the van Goyen’s stretcher, when they returned it to Poland in 1956. But, even if they had, under Nikita Khrushchev, the Soviet Union was continuing Stalin’s non-restitution policy to the Western Allies for cultural property found in the Soviet orbit, let alone to victims of the Holocaust. In contrast, 1956 was the same year that Moscow returned to Warsaw many of the books seized by the Einsatzstab Reichsleiter Rosenberg from the Polish Library in Paris, along with some major returns of captured archives to Poland and other East European Communist-bloc countries. That same year, during the Khrushchev “thaw,” the Memling, the Goudstikker van Goyen, as well as the de Hooch(?), and many other paintings were returned to Poland as part of a much larger Soviet political program of cultural returns to Eastern-bloc countries.

After 10 postwar years in the Hermitage with many other Polish victims of Soviet seizure, the van Goyen was among the fortunate ones that came back to Poland and its home since 1942 in Gdańsk, as Danzig was known in Polish after it became part of Poland in August 1945. In 1956, the van Goyen was first displayed in a Warsaw exhibition of art “rescued by the USSR.”Footnote 81 The Municipal Museum (Muzeum Miejskie) in Gdańsk in 1958 was renamed the Pomerania Museum (Muzeum Pomorskie), and the van Goyen was given a new registration number. Two years later, in October–November 1958, Chałupy nad kanalem (Huts on a Canal in English), as the painting was rebaptized in Polish, was included in a special exhibition of paintings of the seventeenth-century Dutch countryside in the Muzeum Narodowe in Warsaw, which included several other van Goyens, including the two van Goyens among the 25 paintings sold to Poznań during the war (and also returned from the Hermitage). As its only provenance note, the exhibition catalogue claimed the Goudstikker van Goyen came to the Gdańsk museum in 1940. “Without a doubt,” the catalogue claimed, it was “one of the most beautiful paintings of Goyen.”Footnote 82

In 1960, perhaps surprisingly in retrospect, for a painting that had official Dutch postwar claims, the van Goyen from Gdańsk was sent to the Netherlands for exhibition, first to Leiden—the Stedelijk Museum de Lakenhal in June–July 1960—and then to Arnhem—the City Museum (Gemeentemuseum) in July–September.Footnote 83 The exhibition catalogue did not mention its Goudstikker provenance, although, presumably, its stretcher still bore the Goudstikker label. But then neither did Hans-Ulrich Beck mention this provenance in his 1973 catalogue raisonné of van Goyen paintings, published in Amsterdam a decade later (as noted above). With the centennial of the Municipal Museum in Gdańsk in 1972, the Muzeum Pomorskie was granted the status of a national museum—Muzeum Narodowe—with many of its art exhibits still located in the former Franciscan Monastery, dating from the fifteenth century.

Following the fall of the Berlin Wall, the collapse of the Soviet Union, and Poland’s entry in the EU, a 1992–93 exhibition in Gdańsk was entitled “European Dispersed Heritage (Europejskie Dziedzictwo Rzproszone).” The brief multilingual preface to the catalogue mentions early historical acquisitions of the museum; a brief concluding mention of wartime disruption and losses ends with a query that is in reference to paintings that disappeared at the end of the war including those not returned from the Soviet Union: “Is the restitution of this scattered collection still possible?” But not a word about the questionable Nazi wartime purchases by the City Museum.Footnote 84 That year also saw a well-illustrated Polish album, Flemish and Dutch Art of the XVIIth Century in the Collections of the Muzeum Narodowe in Gdańsk: Guide to the Exhibits, with a full-page picture of the van Goyen along with several other wartime purchases from the Netherlands.Footnote 85 Several years later, a 1996 souvenir album with trilingual text (Polish, German, and English) briefly outlines the museum history, bringing together several other Gdańsk museums. Colored plates highlight some of the artistic treasures, again including a full-page illustration of van Goyen’s Huts on a Canal. Memling’s The Last Judgement is featured with images of the triptych as well as several enlarged fragments.Footnote 86

My Gdańsk museum hosts proudly showed me an elegant exhibition catalogue from the Milwaukee Art Museum, Leonardo da Vinci and the Splendour of Poland, published in 2002, which included the van Goyen on a tour of several museums in the United States.Footnote 87 Among the other paintings from Polish museums were two other Dutch Old Masters that Drost had purchased for Danzig during the war—Ferdinand Bol’s (1616–80) Hagar and the Angel (claimed after the war as Dutch state property) Footnote 88 and Jan Rutgers Niewael’s (ca. 1620–61) Young Woman Dressed as a Shepherdess (1635).Footnote 89 Apparently, no concerns, let alone “red flags,” were raised by US authorities about the provenance of any of the paintings from Gdańsk at that time, although Bol’s painting as well as van Goyen’s were registered with the SNK as “missing” from the Netherlands as a result of questionable wartime sales. Disappointingly, that catalogue, published in the United States four years after the 1998 Washington Principles, provides no provenance notes.

CONCLUSION

As is clear from the foregoing case study about the wartime and postwar fate of the Goudstikker van Goyen now in Gdańsk, my findings invalidate the ALIU’s allegation that Göring sold that van Goyen painting to Erich Koch. As mentioned, questions likewise arise about several other paintings included in the same sale listed in the “CIR: Goering Collection” that Göring allegedly sold to Koch, which should now also be corrected in accounts that cite that sale. There is no question, however, about the Goudstikker pedigree of the van Goyen painting in focus here. Lack of clarity may remain about the sequence of transfers between Goudstikker’s death aboard a ship in May 1940 and the Miedl sale to Gauleiter Forster of Danzig in December 1941. Clearly, however, Miedl sold Forster a painting that he and Göring had acquired under “red-flag” circumstances in June 1940, following Goudstikker’s death.

The foregoing provenance analysis of the Goudstikker van Goyen in Gdańsk suggests that similar analysis would be advisable for many other NS-era acquisitions now in Poland, especially those sold to cities in areas annexed to the German Reich. Better scrutiny today in verifying provenance details of Nazi wartime transfers could help avoid potential injustices to Holocaust victims and their heirs as part of the horrendous Nazi cultural ravages and displacements during the war and its aftermath. Certainly, Danzig, which was newly annexed to Germany at the very start of World War II 80 years ago, experienced more than its share of wartime loss in both human and cultural terms, including reduction of much of the city and port to rubble.Footnote 90 In connection with this article, it was distressing to peruse the latest 2017 Gdańsk catalogue compiled by Helena Kowalska of 405 paintings from the wartime Danzig Stadtmuseum still missing since the war, including details and quality image of the Esselens (see Figure 9), sold to Danzig Gauleiter Forster together with the van Goyen.Footnote 91 For those items not destroyed at the end of the war, it will take considerable provenance research in attempt to track their present location. Some that had been evacuated to Thuringia in 1944 may still be in Russia, along with many files from the Danzig City Archive that have never come home from the war. But many questions arise about the rest. For the incoming works of art acquired by Danzig’s Nazi leadership in efforts to Germanize the Stadtmuseum, more research is also needed to determine their provenance before their sale to Danzig in the NS-controlled Germanized Dutch art market during occupation of the Netherlands. How many of them came from other Nazi victims abroad, including Holocaust victims or survivors? The items in the Drost Reference Drost1943 volume registered as “missing” from the Netherlands in the SNK records in The Hague, together with the SNK 1946 list of paintings sold to Danzig (Figure 11), and the 2018 Herkomst Gezocht “Poland Report,” to be discussed below (note 103), all suggest that the van Goyen and the Gipsy Fortune Teller may be only the tip of the iceberg.

In a preliminary check during numerous research visits to The Hague since my visit to Gdańsk, with the help of Herkomst Gezocht specialists, I identified postwar SNK loss-registration/claims and related documents for at least 10 of the other paintings Drost pictured in his 1943 published catalogue of early wartime Danzig Museum acquisitions.Footnote 92 Colleagues in the BHG were quick to respond, recognizing and confirming the need for more serious attention to their Dutch provenance and suggesting willingness to assist Polish specialists in pursuing the needed investigation, if any were so inclined.Footnote 93 The initial findings suggested that sources are readily available for further analysis of more paintings, together with resources of the RKD for paintings by Dutch artists.Footnote 94 Possible joint collaboration in provenance research has already been suggested informally to specialists in the Polish Ministry of Culture and National Heritage as well as the Foreign Office on several occasions since my visit to Gdańsk and my participation in the Polish Ministry of Culture-sponsored 2014 conference on Polish cultural war losses in Kraków.

Today, even more SNK and other sources relating to the wartime Dutch art market are readily and openly available for research in the Netherlands. Of particular importance in this context, the BHG completed an upgraded database in 2017 with online public searching capacity (in English and Dutch), providing access with images to postwar SNK registration forms for Dutch wartime art losses as well as the so-called NK Collection of art returned to the Netherlands but still held as Dutch state property.Footnote 95 The project resulted from support of the Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, the National Archives, and the RKD, together with major initiatives and contributions from the Conference on Jewish Material Claims against Germany (Claims Conference).

Subsequent to the launch of this upgraded Herkomst Gezocht online facility, the Claims Conference sponsored an exploratory investigation by BHG specialists, using the new database with Dutch postwar SNK registration files of “missing” works of art, to list those involved in potentially suspicious wartime sales to Poland. To be sure, again reflecting the findings on the SNK’s 1946–47 lists, the “suspicious” sales were highest for the western Reich-annexed and wartime Germanized cities of Posen and Breslau, along with Danzig, which became part of Poland in August 1945. Understandably, many of the same missing art items on the SNK’s 1946–47 lists discussed above surfaced again. The resulting preliminary “Poland Report” lists 81 art items (many with images) sold to cities (including those three) that are now part of postwar Poland (since 1945); most of those items sold to Danzig during the war overlap with those on the SNK’s 1946–47 lists of art works “missing” from the Netherlands (Figure 11), which together with the lists for Posen and Breslau are included as Appendix III. The “Poland Report” also covers the Goudstikker van Goyen and the two other Dutch paintings sold to Alfred Forster in the same 12 December 1941 transaction; although as documented above, today the Esselens remains on the Gdańsk “missing” list. More paintings sold to Danzig may well be found as research continues. Half of the Danzig early wartime acquisitions purchased in the Netherlands are pictured in the Drost Reference Drost1943 catalogue, but others were acquired after that publication. Five of the 20 missing Dutch paintings sold to Danzig, listed in the preliminary “Poland Report,” including the Esselens, never returned to Danzig after the war and appear in the 2017 Gdańsk catalogue covering some 405 paintings missing from postwar Gdańsk; but none of those 20 listed ever returned to their prewar homes in the Netherlands.Footnote 96

Dutch colleagues involved have subsequently expressed considerable interest in assisting Polish museum curators or advanced postgraduate students involved in further joint research on the Gdańsk items listed – if there would be a Polish inclination for a collaborative effort to establish transparent provenance attributions. Recently, more formal suggestions for such joint research have been raised in Poland through contacts of the Claims Conference and the World Jewish Restitution Organization. Early in 2019, BHG operations were transferred and became directly coordinated with the newly established Expertise Centre Restitution (Expertisecentrum Restitutie) within the NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies in Amsterdam, under the Royal Netherlands Academy of Arts and Sciences. Administrative reorganization affecting these research agencies in the Netherlands may alter working relationships and delay a possible joint project. Some informal contacts are already underway, encouraged, for example, by the fulsome assistance of the Gdańsk museum curator in response to editorial queries in connection with this article. It can be hoped that this newly reorganized Dutch Expertise Centre, which now incorporates the BHG, will encourage and further promote the joint cooperation in provenance research badly needed on these issues in the future.

At the time of my 2014 Gdańsk visit and subsequently, an image of van Goyen’s Huts on a Canal was displayed on the Gdańsk Muzeum Narodowe’s website along with quality images of the other Dutch and Flemish paintings held by the museum, including many of those that appeared in Drost’s account of his wartime acquisitions and in subsequent Polish publications. Disappointingly by 2017, and still currently in 2019, that webpage is no longer displayed. In September 2017, an unidentified image of the van Goyen painting could be found within a large sidebar collage on one of the museum webpages; by 2019, that collage has also disappeared.Footnote 97

Gdańsk museum officials kindly and openly received me as an academic historian, not as a representative of any potential claimant or a specialist in restitution law, which I am not. In my own informal conversations with Polish specialists, as well as with Dutch specialists in the Netherlands, after my research uncovered so many “suspicious” Nazi-era acquired paintings in Polish museums, I have often suggested joining hands with Dutch and Polish specialists in a collaborative provenance research undertaking, if support could be found. Perhaps, as a start, further research would be in order on other paintings involved in “suspicious” sales acquired during the war by Forster and Drost as Nazi leaders in Danzig for its Stadtmuseum. Even with initial results, it might be worth considering restoration of the website display of the early Dutch and Flemish treasures in the Muzeum Narodowe in Gdańsk with expanded already researched provenance data. The initiation of such efforts might help explicate earlier “red-flag” press inquiries and reassure the public internationally. It is not my place to adjudicate the legal status of the van Goyen painting now hanging as part of a lovely exhibit in the Muzeum Narodowe in Gdańsk. But, at least for the sake of transparency in the near future, as a component of international Holocaust education and remembrance, it might be nice to see a plaque mentioning its provenance in the collection of a prominent Holocaust victim, who was perhaps one of the best-known and respected interwar Dutch dealers in Old Masters and who had a special personal interest in that painting.

Even in 2019, as we celebrate the tenth anniversary of the Terezín Declaration and the eightieth anniversary of the start of World War II with the German armed annexation of Danzig, Poland still lacks a viable procedure for restitution claims from individual Holocaust victims and their heirs, both within the country and from abroad. Reference was accordingly made in the introduction to the 2015 criticism of the lack of progress in Poland “towards implementing the Washington Principles and the Terezín Declaration.”Footnote 98 In the years ahead, concerned specialists as well as the public at large will undoubtedly follow the extent to which Poland will conform to the 17 January 2019 European Parliamentary Resolution on Cross-Border Restitution Claims of Works of Art and Cultural Goods Looted in Armed Conflicts and Wars. Footnote 99 Until the Polish government is prepared to recognize and implement such European legal and moral standards with reciprocity, however, there is scant hope that Goudstikker’s charming van Goyen could easily return to the Netherlands, let alone to the United States, where the Goudstikker heirs now reside as citizens. But, in the meantime, without even a label of transparent provenance, can that charming painting still comfortably continue to hang proudly in the Gdańsk Muzeum Narodowe?