How do archaeologists, governments, law enforcement, and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) respond to a hole in the ground, a hole that is the direct result of archaeological site looting? Demand for Early Bronze Age archaeological objects (3600–2000 bc) has resulted in decades of illegal excavation, leaving thousands of holes in the surface of ancient sites along the Dead Sea Plain in Jordan. While site surveys (aerial and pedestrian), mapping, oral interviews, and archival research help to identify patterns in looting, none of these tools alone is sufficient to reveal looters’ profit motives or the potential income derived from looting and selling antiquities. Instead, a comprehensive suite of methods allows the Follow the Pots (FTP) and the Landscapes of the Dead (LOD) projects to gain valuable insights into the past and the present regarding these holes. Information derived from such an approach may strengthen current anti-looting measures and lead to new protection mechanisms and programs. The following is an examination of the (w)hole picture: individual and institutional responses to looters’ holes at Early Bronze Age sites along the Dead Sea Plain in Jordan—diverse reactions with the common goal of preserving Jordanian cultural heritage.

DOCUMENTING THE HOW AND THE WHY OF HOLES

Typically, archaeologists focus on making systematic holes in the ground in order to access information about ancient people, lives, cultures, and traditions. The contents of these holes provide data that allow for the acquisition of knowledge and for reconstructions of the past. Holes of this nature are usually made with the permission of a governmental ministry, heritage organization, or landowner. But what of the holes that are the result of illegal excavation of archaeological sites without the permission of the landowner or the relevant governmental authority, an action that occurs daily across the globe? Sites are routinely mined for objects, for private or institutional consumption, as part of the commodity chain involving looters, intermediaries, dealers, and, eventually, consumers.Footnote 1 When an item is illegally removed from its archaeological find-spot, all of the associated contextual information is lost, compromising our comprehension of how, when, and where it was used in the past. An artifact’s contextual information can be more important than the object. The demand for artifacts causes illegal looting at sites, which destroys the archaeological context of an object, whether at a known or previously undiscovered site.

Governments, aid agencies, cultural heritage non-profit organizations, and academics grapple with how best to deal with the act of looting and its resultant holes. These varied entities all want to understand the mechanics of looting—the where, the how, the why, and what happens to looted artifacts that are illegally removed from the ground. Gathering this knowledge enables assessments of the efficacy of current laws, policies, and programs, with an eye to the ultimate goal of protecting and preserving cultural heritage.

Individuals, institutions, and states wrestle with monitoring site destruction during times of unrest,Footnote 2 warfare,Footnote 3 development,Footnote 4 and economic downturn.Footnote 5 In addition to archaeological site prospection and survey applications, archaeologists and cultural heritage specialists also turn to satellite imagery to assess archaeological site looting and destruction.Footnote 6 In situations where reconnaissance on the ground is impractical or impossible, satellite imagery is an incredibly useful tool in assessing and quantifying damage to sites as demonstrated by recent studies of Afghanistan, Egypt, Iraq, and Syria.Footnote 7 Looting is not limited to the Middle East; on a global scale, the outlook is grim.Footnote 8 Together, these recent studies and those in progress demonstrate clearly that there are many holes created by the looting of archaeological sites and landscapes—holes that have a negative effect on understanding the past.

The driving forces behind looting are far more complex than is often recognized. Motivations for looting can involve notions of nationalism, the forces of globalism, conflicting preservation and management plans, colonialism, long-entrenched traditional practices, and even quests for buried treasure.Footnote 9 According to archaeologist Michael Press, the destruction of antiquities and sites to find hidden treasure was a common trope in Western writing about the early exploration of Palestine, whether in popular literature or in scholarly accounts.Footnote 10 Press recounts that, in surveying Lebanon for the Palestine Exploration Fund in 1869, Charles Warren reported: “The upper part [of the face of a possible deity on a temple at Rakhlah, Syria] has been blown away with gunpowder, probably in hopes of finding treasure inside.”Footnote 11 At its core, most looting is triggered by the indiscriminate demand for archaeological material, regardless of provenance or documentation.Footnote 12 It is a simple economic equation of supply and demand. As demonstrated below, there is demand for archaeological artifacts from sites associated with the people and places of the bible, which has resulted in looting at various sites along the Dead Sea Plain in Jordan.Footnote 13

HOLES ALONG THE DEAD SEA PLAIN, JORDAN

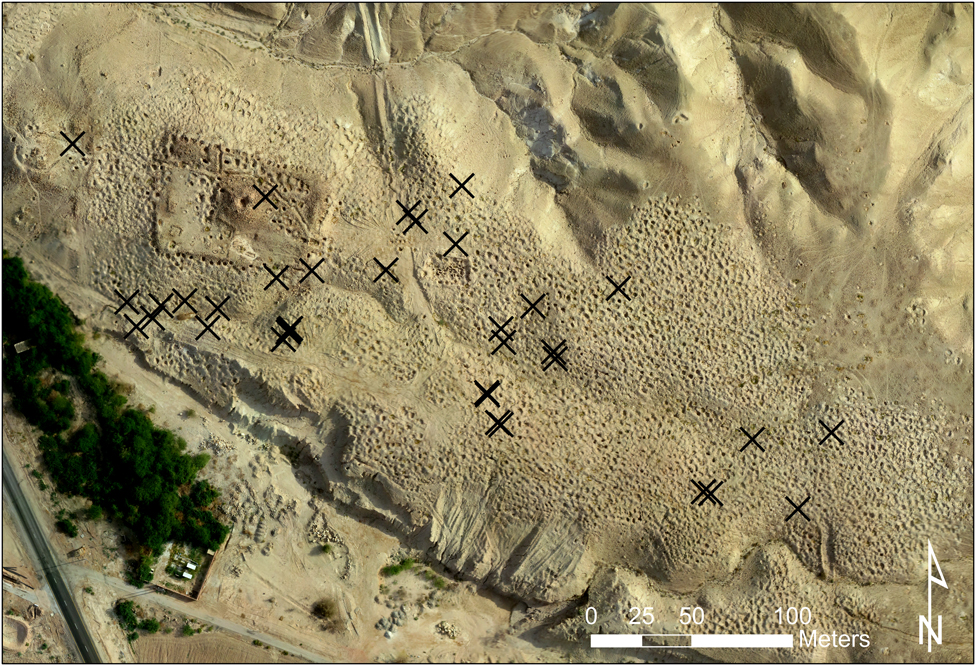

A series of Early Bronze Age mortuary and domestic sites (Bab adh-Dhra’ and Fifa) along the Dead Sea were identified by early explorers as two of the biblical cities of the Dead Sea Plain (see Figure 1).Footnote 14 This ongoing association with the Old Testament “time of the Patriarchs” or the “City of Sin”Footnote 15 led to a sustained demand for items (usually ceramic vessels) with Holy Land associations. In the early 1970s, while carrying out archaeological surveys in the southeastern plain of the Dead Sea in Jordan, Walter Rast and R. Thomas Schaub reported some negative interactions such as looting, quarrying, and unauthorized construction activity at the Early Bronze Age IA cemetery site of Fifa (circa 3600–3200 bc). With thousands of cist tombs, Fifa sits on a promontory that overlooks the southern tip of the Dead Sea (Figure 2). Rast and Schaub noted a few looted tombs, a scattering of ceramic fragments and human remains on the surface of the site and quarrying along the southern and western edges of this cemetery.Footnote 16 In the archaeology of the southern Levant, this site represents an important resource on burial practices during this period, as Fifa is one of only four large known Early Bronze Age cemeteries.Footnote 17

Figure 1. Early Bronze Age sites, Dead Sea Plain, Jordan (courtesy of Austin (Chad) Hill).

Figure 2. UAV-derived orthophotograph of Fifa, with 2001 excavations by Mohammad Najjar highlighted by the box in the center of the image (courtesy of Austin (Chad) Hill).

To date, only two small seasons of systematic excavation have been conducted at Fifa: a three-week season in 1989–90 by Rast and SchaubFootnote 18 and a salvage excavation in 2001 by Mohammad Najjar,Footnote 19 the latter carried out on behalf of the Jordanian Department of Antiquities (DoA) in response to site destruction by looters. Since 2011, the FTP project has focused on documenting and assessing the mortuary site of Fifa.Footnote 20 Looting has continued at the site despite the efforts of the Jordanian DoA and local site protection initiatives. Where there were once graves, there are now holes, 3,723 of them (Figure 3). As a part of the FTP project, interviews conducted with Dead Sea region residents who illegally excavate at local sites confirm an overall generalization that individuals and groups loot in the agricultural off-seasons when there is no other full-time work. Digging is a viable economic activity because looters know that a “big black car” from Kerak (the closest big city) or Amman will come by the site and buy whatever they recover.Footnote 21 Knowing that there are systems in place that will reward the person producing the holes encourages the vibrant enterprise of creating holes. Archival records and oral histories confirm the networks in Kerak and Amman to be the driving force behind the organization of local labor to illegally excavate at the sites in order to procure saleable items (Looters 2, 5, 12).Footnote 22 This practice has persisted for generations, with particular families involved in various nodes along the artifact pathways.

Figure 3. Map of 3,723 looters’ holes at Fifa (courtesy of Austin (Chad) Hill).

Decades of illegal excavation at the Early Bronze Age sites (3600–2000 bc) along the Dead Sea Plain have resulted in well-established corridors of trade and thousands of holes. The responses of archaeologists, government, law enforcement, and NGOs to a hole in the ground are distinct, some more effective than others, but all with the common purpose of gaining greater insights into the processes of looting with the aim of increased protection of the archaeological heritage of Jordan.

RESPONDING TO HOLES IN JORDAN

Jordanian Government and Law Enforcement’s Response to Holes

Over the years, the Jordanian government, the DoA, and local law enforcement have tried different strategies to combat illegal excavation at the sites along the Dead Sea Plain, but with limited success. In 1976, Jordan’s legislature passed a law (Antiquities Provisional Law no. 12) banning the legal trade in antiquities. In enacting this law, various authorities charged with the protection and monitoring of archaeological objects, sites, and monuments hoped that prohibiting the trade would stop looting. In a searing indictment of the ineffectiveness of the law, the former Jordanian DoA director, Ghazi Bisheh, remarked: “Instead of eliminating or even reducing the trade in antiquities, which was the aim of the new law, a surge in illicit excavations and pillaging of archaeological [sites] became noticeable along with the creation of a brisk black market.”Footnote 23 Archival and ethnographic research by the FTP project confirms Bisheh’s observations on the increase of illegal excavations at the Dead Sea sites; in the post Antiquities Provisional Law no. 12 era, artifacts from this area have found (and continue to find) their way into local, regional, and international collections through an intricate network of looters, dealers, and buyers.Footnote 24

In response to this looting, the local police force, in collaboration with the regional office of the DoA, placed a fence and guards at the site of Bab adh-Dhra’. The fence was stolen overnight, and the guards proved to be ineffectual in the face of a great number of looters and the size of the site. Limited governmental resources, ongoing demand, and extremely effective national and international trade networks allowed for a persistent business in the sale of Early Bronze Age material from the Dead Sea Plain. In its attempt to think of creative solutions for the issue of looting and recognizing the connection between demand for archaeological material and the looting of sites, the Jordanian DoA instituted a “buy-back” program.Footnote 25 Spurred by mid-1990s international news accounts of looting in the Ghor es-Safi region,Footnote 26 and the lack of sustained government response to the worsening situation,Footnote 27 the DoA developed a strategy for cultural heritage protection in collaboration with local and foreign archaeologists.Footnote 28

Under the auspices of the Jordanian DoA, and with the approval of the minister of tourism and antiquities, direct purchasing from looters of some of the more important antiquities began. The program consisted of working with looters to retrieve information on their activities; there were no recriminations and no arrests. Looters would be paid for the artifacts in their possession if they turned over the item and the associated information about the find-spot to the relevant authorities.Footnote 29 Looters, archaeologists, and DoA representatives returned to the original area of looting in order to document the archaeological context of the material,Footnote 30 and all looted objects were recorded, photographed, and collected by the Jordanian DoA for eventual placement in a museum.

According to Konstantinos Politis, an archaeologist who has worked for decades in this region, this program had the multiple effects of gaining local confidence and acquiring important archaeological material for local and national museums, all the while disrupting the well-established trade networks.Footnote 31 Artifacts were purchased, studied, and published.Footnote 32 With the general archaeological find-spot for items from the Dead Sea Plain established, some are now housed at the Museum at the Lowest Place on Earth in Ghor es-Safi.Footnote 33 The question of whether the government-sponsored buy-back program actually encouraged a greater amount of looting has yet to be studied, but it is clear that this program did not stop illegal excavation. Looting continued to produce more holes, to affect the reconstruction of ancient life in the region, and to compromise the archaeological landscape of this region. How then do archaeologists respond to these holes?

Archaeological Response to Holes

Responding to Holes at Fifa, a Case Study Using Drones

The first phase of the FTP project mapped the site and carried out oral interviews with those who interacted with the cemetery site of Fifa. This 2011 field season was successful in some respects as well as highlighting some of the shortcomings associated with the project methods.Footnote 34 One such deficiency was the discrepancy noted between the pre-season analysis of Google Earth© satellite imagery of the site, used to quantify the number of looted graves, and the realization that not every hole identified from space is an actual ancient tomb.Footnote 35 Standing in the lunar landscape of Fifa, comparing satellite images (with limited resolution) with what was on the ground, led to the radical idea of using drones to gather data with much greater spatial resolution, which would allow for the more accurate identification of individual pits and the potential differentiation of unsuccessful looters’ pits from actual looted graves. It was in this way that the Landscapes of the Dead (LOD) research project was born. To this end, drones—both fixed and rotary wing—are being used to build a (w)hole picture of the mortuary landscape, including looting activity and holes.

As part of a comprehensive approach to the Early Bronze Age IA mortuary landscape at Fifa, and in cooperation with the Jordanian DoA under the umbrella of the FTP, the LOD project is using unpiloted aerial vehicles (UAVs), or “drones” as they are commonly known, to study the scale and pace of natural and cultural landscape modification at Fifa. The integrated approach of the LOD project combines low elevation aerial photography, and the resultant spatial data for digital mapping, pedestrian survey, and ground truthing, with oral interviews with the constituents who interact with the site and its objects. This innovative interdisciplinary and collaborative endeavor provides a thorough change-over-time examination of the effects of looting and landscape modification on the local community and the archaeological record, while, at the same time, assessing the impact of the Jordanian DoA’s anti-looting campaigns, national laws, and local community outreach programs.

Mindful of recent backlash against the use of drones, remote sensing, and satellite imagery—what archaeologist William Caraher refers to as a type of “technological solutionism—new-fangled technologies as a key to solving some of the ills affecting archaeological fieldwork”Footnote 36—the LOD project sought to overcome the impersonal nature of “eyes from the sky,” which can have a dehumanizing effect wherein the landscape is considered to be a part of a scientific investigation devoid of local interaction.Footnote 37 The LOD project, of which drones are only one part, includes multifaceted modes of research and analyses, community engagement, and knowledge sharing. This unique program provides a methodology for better understanding the ancient and modern interactions with the site. Implicit and explicit in this approach is an acknowledgment of, and a focus on, the ethical implications of operating UAVs and the potential negative and positive impacts of this research on the local communities of the region, an often missing element from many research projects.Footnote 38

The merit of using drones (ease, efficiency, and affordability) to document landscape features,Footnote 39 archaeological excavation areas,Footnote 40 and subsurface (thermal and near infrared) surveysFootnote 41 is well established, but the need for ground-truthing sites is echoed by most, if not all, practitioners who utilize satellite imagery, drones, or both for landscape interpretation and prospection. Pedestrian surveys are a vital component of archaeological landscape assessment;Footnote 42 without pedestrian ground surveys, features are undoubtedly missed or misinterpreted. In 2013, through comprehensive ground truthing and archival research, and in collaboration with a local archaeologist, an important discovery was made regarding the occurrence of looting, which was not identified using Google Earth© or even with the unprocessed drone images. Many of the Early Bronze Age cist tombs share a single wall, a characteristic building technique confirmed by the earlier excavations of Mohammed Najjar (Figure 4).Footnote 43 Even where looting is most concentrated at Fifa, there are many undisturbed graves covered by the back-dirt piles of previously looted adjacent graves. However, the graves often share a wall, a phenomenon of which the looters are well aware. In an efficiently destructive approach, pristine graves can be rapidly accessed by digging sideways through the wall of a previously looted grave. It is much easier to dig sideways between two graves than to dig down from the surface through the overburden and the large limestone capstones covering the tombs.

Figure 4. Image of adjacent cist tombs sharing a single wall (courtesy of Morag M. Kersel).

The LOD project undertook aerial drone survey at Fifa from 2013 to 2016. Over the course of four seasons, as technology improved, a variety of fixed-wing and rotary-wing drones were used. The aerial surveys were designed to record the site at centimeter-level resolution in order to generate undistorted orthophotographs (see Figure 2) and digital elevation models (DEMs) of the site. After photogrammetric processing using Agisoft Photoscan Pro, the resulting data were analyzed via visual inspection and DEM comparison in order to identify new destruction at the site each year (Figure 5). Comparisons between 2013 and 2014 change over time, using the difference between annual DEMs, indicate discernable modifications to the landscape in the form of new holes as well as new positive change in elevation due to the creation of spoil heaps (Figure 5A), which are also visible in the orthophotographs as fresh (moist) dirt (Figures 5B and 5C), from new looting episodes, often alongside visible new pits (Figure 5D). Although, initially, it was unclear why there would occasionally be new back dirt adjacent to a previously looted cist grave, as mentioned above, pedestrian survey confirmed that sideways digging between looted and unlooted tombs created new back-dirt piles (positive change) without obvious new holes (negative change), a trend confirmed in later seasons (2015 and 2016).

Figure 5. Evidence for a single new hole: (A) difference in elevation between 2013 and 2014 (positive change is white, negative change is black); (B) orthoimage from 2013; (C) orthoimage from 2014; (D) hill shaded digital elevation model showing shape of new hole (courtesy of Austin (Chad) Hill).

One incentive for using drones to record change-over-time data is not only to examine the transforming landscape but also to provide comprehensive maps for use by the DoA, heritage organizations, and local communities, which may assist in the greater awareness of archaeological site destruction.Footnote 44 The high resolution diachronic data generated from the air, in conjunction with archival research, pedestrian surveys, site mapping, and oral interviews on the demand for, and the movement of, looted material are used to evaluate site protection strategies and to develop local community outreach programs, resulting in a comprehensive model that might be applied to other at-risk sites and regions.

Results of the Archaeological Response to Holes

There are a number of important results of the site monitoring with UAVs over four seasons of investigation at Fifa. First, despite the continued efforts of the DoA and local community programs of the Petra National Trust (PNT), looting persists. The individual reasons behind looting vary, but, in the final analyses of the trade in undocumented antiquities, the driving force is demand; institutional and individual demand for ceramic vessels from the Early Bronze Age results in the looting at Fifa.Footnote 45 Investigating this demand—another element of the FTP project—is a topic for another article, but there is compelling evidence that demand is driving the ruin of this (and other) landscapes.Footnote 46 As a component of the overall picture of site destruction, looting, and demand for archaeological artifacts, conducting oral interviews with various actors (dealers, looters, tourists, collectors, and intermediaries) provides an increased understanding of the constituent elements in the illegal trade in Early Bronze Age material from the Dead Sea Plain in Jordan, thus supplying complementary data to the UAV flyovers. Demand is for the ceramic vessels alone, not the other associated grave goods from the cist tombs.Footnote 47

A second outcome of this research is an understanding of what remains at the site, which at first glance appears to be completely decimated. Though looting at the site continues to have a devastating effect, it would be imprudent to believe that the cemetery at Fifa is completely destroyed. In the area excavated by Mohammad Najjar in 2001, the density of tombs is estimated at approximately 25 graves per 100 square meters. The area covered by the identified boundaries of the site is approximately 70,658 square meters. Assuming that the density of burials across the entire site is similar to the results of this methodically excavated area, then the total number of burials at Fifa could be as high as 17,664. The 3,723 documented looting pits might then account for only 21 percent of the estimated total burials at the site. While this simple calculation likely overestimates the total number of graves at Fifa, even in the most disturbed part of the site, the number of successfully looted pits rarely approaches a density to match that of the scientifically excavated area of 2001. In these densely looted areas, there are between 5 and 10 looters’ pits per 100 square meters. Thus, even in heavily damaged areas, there may still be twice as many undisturbed graves as looted ones. There are many graves left to loot, and parts of the site remain intact.

The following is a detailed description of the quantitative and qualitative outcomes of a thorough methodology, which allows the LOD project to gain valuable insights into landscape change and the economic possibilities generated as a consequence of the holes at Fifa. Working collaboratively with the local authorities, the DoA, and NGOs allows for the exchange of information on these elements of looting in the Dead Sea region, which may aid in future anti-looting initiatives.

Results from Season 2013–14: New Holes, New Insights

Thirty-four new pits were dug between the 2013 and 2014 field seasons (Figure 6). While this is only a small proportion of the total holes at the site (less than 1 percent), it still represents a significant number of looted artifacts and potential prices realized. If each grave might contain an estimated 6–30 ceramic vessels, then the total number of saleable vessels from these 34 graves could be as low as 204 and as great as 1,020.Footnote 48 In today’s market, these pots sell for between $30 and $150, resulting in a low total estimate of $6,120 and a high estimate of $153,000 (see Table 1). Oral interviews with local looters (Looters 7, 8, 12) confirm that they receive between three and five Jordanian dinars ($4–7) per pot, which means they could be making roughly between 1.5 percent and 15 percent of the final price paid by the consumer.Footnote 49 This estimation corroborates the findings of Neil Brodie and Daniel Contreras who suggest looters make about 1 percent of the final sales price,Footnote 50 and the work of Jerome Rose and Delores Burke with looters in northern Jordan who earned about 15 percent on the sale of illegally excavated items.Footnote 51 In high and low estimates, looters could realize between $816 and $7,140 by illegally excavating 34 holes. The average yearly salary in Jordan is $5,160,Footnote 52 and while there is no suggestion that a single looter or even a group of looters is reaping all of the financial rewards, looting at Fifa has the potential to be a modestly lucrative endeavor.

Figure 6. Map with new looters’ pits 2013–14 (courtesy of Austin (Chad) Hill).

Table 1. Quantifying looted holes at Fifa

The 34 new holes were concentrated, not surprisingly, in the area of the main wadi (river bed) that runs through the site and down along the lower slopes in the southwestern edge—areas less visible from the road. Two types of looting are clearly evident at the site: systematic and opportunistic. Empty plastic water bottles, broken tools, sardine cans, and the detritus left by professional looters suggest individuals choose locations in the wadi or on the southern slope in order to dig in anonymity.Footnote 53 During this period, looters also methodically revisited old holes in order to dig in a sideways fashion as described previously. Archaeological and ethnographic data indicate there is also ad hoc looting by bored individuals with nothing to do, digging around in an already heavily looted landscape.Footnote 54 Evidence in the form of broken liquor bottles suggests that the lower slope to the southwest is a favored haunt for local youth, resulting in coincidental, rather than targeted, looting. Whatever the motivation, artifacts are purchased by intermediaries from the larger cities of Kerak and Amman and then traded through the extensive national and international networks (Dealers 17, 49).

Results from Season 2014–15: A Decrease in Looting Activity

An assessment of the maps between 2014 and 2015 indicate just three new holes during this period, which were analyzed using the same set of criteria that generated the following statistics (Figure 7). The estimated number of saleable pots from the three new graves is between 18 and 90. Today’s market prices of $30–$150 per pot provide a low total estimate of $540 and a high estimate of $13,500. Based on oral interviews with looters, the potential income generated from the illegal excavation of three holes could be between $72 and $630. Compared with the previous and subsequent years of analyses, there were fewer holes during this period, which results in questions surrounding the factors that are leading to less looting at Fifa. Between 2014 and 2015, a series of public outreach programs carried out by the PNT, in collaboration with the team from the FTP project, formed part of an all-encompassing approach to addressing issues related to archaeological site looting and the demand for artifacts (see the section on the response of NGOs to holes below).Footnote 55 Staff from the Jordanian DoA Safi Inspectorate and the Museum at the Lowest Place on Earth provided greater oversight and management of the site, with more on-site foot patrols and drive-by site monitoring. Moreover, a third possibility was uncovered through ethnographic interviews with buyers (Tourists 12, 24, 113) and sellers (Dealers 4, 8, 17, 29, 47, 49) of Early Bronze Age ceramic vessels for sale in the legal market in Israel. During the summer of 2014, there were fewer tourists in the region due to the Israel–Gaza conflict, which occasioned a downturn in artifact sales in general. Interviews with dealers also indicated that there was no demand for the Early Bronze Age pots, a consequence of changing consumer tastes (Dealers 4, 8, 17, 29, 47, 49). Russian icons were, and still are, the new “hot” item for religious pilgrims and other tourists (Dealers 4, 18, 23, 47). Are fewer holes at Fifa the result of effective outreach efforts, changing consumer tastes, or the downturn in regional tourism? Are our results skewed based on the time of year we surveyed the site (earlier in 2015 than previous or subsequent years) versus the potential peak season for looting, which is between harvests (see Kersel and Chesson Reference Kersel and Chesson2013b). Or is this season an anomaly?

Figure 7. Map with new looters’ pits 2014–15 (courtesy of Austin (Chad) Hill).

Results from Season 2015–16: Looting Activity Returns

In the analysis of aerial survey data between the 2015 and 2016 seasons, 24 new holes were recorded (Figure 8). Mapping the holes revealed an interesting pattern of looting. Along the northern extent, there are four new holes beyond the edge of the site, which were undoubtedly unsuccessful excavations. Looters are moving beyond the previous areas of concentration in the hope of finding new and untapped parts of the site. However, previous looting appears to have already effectively identified the margins of the cemetery. New holes are also apparent in formerly looted and scientifically excavated areas. A new cluster of holes is evident to the west of the 2001 scientific excavations of Mohammad Najjar (Figure 9). In the back-dirt pile of this looting, a complete vessel was recovered, suggesting perhaps novice looters or a certain degree of sloppiness in technique (Figure 10). Interactions with looters at the site have included groups of kids (aged between 8 and 16), seasoned regulars, and bored teens, who are mentioned above. The varying levels of experience and expertise in looting are evident in the tools left behind by the looters, the location of looting holes, the artifacts left behind, and the methods visible through ground truthing.

Figure 8. Map with new looters’ pits 2015–16 (courtesy of Austin (Chad) Hill).

Figure 9. Close up of orthophotographs demonstrating looting near the 2001 excavations: (A) 2015 and (B) 2016 (courtesy of Austin (Chad) Hill).

Figure 10. A complete discarded pot (courtesy of Austin (Chad) Hill).

Applying the same model of analysis based on patterns of grave goods identified by Rast and Schaub in the 1990 excavation at Fifa, the 24 new holes produced the following figures. An estimated low number of 144 pots to a high of 720 pots might have been recovered from the 24 holes, which could generate anywhere from a low total of $4,320 to a high of $108,000 in estimated sales. The potential income earned by the looters of these 24 holes is estimated to be between $576 and $5,040, which would be meaningful sums for the local residents of the Ghor es-Safi region. The 24 new holes recorded between 2015 and 2016 demonstrate an increase in looting in comparison to the 2014–15 season, where only three new holes were documented. The results from the 2014–15 season remain an irregularity.Footnote 56 Further investigation into the reasons for the low number is ongoing and could include the local economy, artifact demand, trade networks, and regional instability. Some general observations are possible based on the four seasons of drone flyovers (see Table 1). Analyses of the maps in conjunction with pedestrian surveys indicate that the looting of 61 holes at Fifa since 2013 has the potential to realize a total financial gain from sales in the range of $10,980 to $274,500. This does not reflect the prices paid to the looter (typically between $4–7 per pot), which could result in profits from looting between $1,464 and $12,810. Nor do these figures factor in how many hands the artifacts pass through in the associated financial transactions leading to the eventual purchasers; they only reveal the number of potential looted pots and the final sales price to the buyer. Quantifying a lifetime of looting at Fifa provides some stunning statistics from a single site (Table 2). Between 1989 and 2016, the looting of 3,723 graves potentially produced between 22,338 and 111,690 pots, which may have sold for between $30 and $150 per pot, resulting in prices realized between $670,140 and $16,753,500. Looters, paid anywhere from 3–5 Jordanian dinars ($4–7) for each pot, could possibly have earned 66,600 Jordanian dinars and 555,000 Jordanian dinars ($88,800 and $777,000).

Table 2. Quantifying a lifetime of looting at Fifa

Consumer tastes for items with a biblical association never completely go out of fashion, as attested by 27 years of looting in order to meet demand in the marketplace.Footnote 57 People buying Early Bronze Age pots from this region are typically tourists and religious pilgrims to the area who want to leave with a small memento of their trip.Footnote 58 The pots are prosaic, inexpensive keepsakes manufactured in the past that evoke a message about an associated biblical place. Bab adh-Dhra’ has been identified not merely as a city of the plain but also as the biblical Sodom, a city synonymous with sin. According to data collected, it is these biblical associations that make artifacts from the Dead Sea Plain sites desirable. Dealers interviewed during the summers of 2016 and 2017 indicated that they were already seeing a rise in demand for objects (including Early Bronze Age pots) with connections to the Holy Land (Dealers 6, 8, 23, 47, 49). The antiquities market is complicated, with illegal Jordanian artifacts legitimately available for the willing consumer in Israel, on eBay, and in other markets.Footnote 59 The desire for Early Bronze Age pots, as the drone survey and the oral interviews demonstrate, results in more holes. Given the continual demand for Holy Land material, the question of why there were only three holes between 2014 and 2015 remains. Perhaps recent NGO response to holes could be a factor in the fewer holes at Fifa?

NGO Response to Holes

In response to holes at archaeological sites across Jordan, the PTN, a non-governmental agency, has worked with the FTP project to develop a module for their Petra Junior Rangers and the Youth Engagement Petra programs on the illegal excavation of artifacts and the trade in antiquities. Looting Stops Us Learning is a series of workshops targeted at Jordanian youth, aged 12 to 18.Footnote 60 The workshops are targeted specifically at raising an awareness of one of the most destructive forces that threaten Jordan’s cultural heritage—the demand for undocumented artifacts—which results in the devastation of archaeological sites to meet market demand. Over the course of a day, students move through a heritage site (for example, the Citadel in Amman, Petra, Umm el-Jimal, or Umm Qais), the associated site museum, and the visitor center, completing a series of directed activities that focus on looting, the sale of antiquities, and the destruction of heritage sites.Footnote 61 Understanding demand for archaeological material and the connection to looting is one of the main goals of this educational program. In its response to holes, the PNT hopes that cultural heritage protection will be an indirect outcome of workshops aimed at increasing esteem for the past, clarifying the connection between tourism and site preservation, and implementing anti-looting programs in Jordan. Evaluations of the pilot workshops carried out between 2014 and 2015 at Petra revealed that 41 percent of participants rated the program as excellent and 55 percent rated it as very good.Footnote 62 Responses showed that some 60 percent of participants agreed that looting leads to a misunderstanding of the past, which is a key objective of the workshops.

During a week that the FTP project was in the field, three different groups of looters were encountered. Of these three groups, one was comprised of five kids ranging in age from about 8 to 14 using the very same tools and techniques as the adult looters. Clearly, any anti-looting initiatives need to focus not only on stiffer penalties and policing but also on outreach programs with younger generations. The PNT practicums on looting and site protection are an excellent first step in introducing the topic to a younger generation of Jordanians; undoubtedly, there are future collectors and looters in the participant pool at the PNT workshops. Many of the young people who participated in the PNT program agreed that it would be difficult to arrive at solutions to looting without understanding why people demand artifacts. Whether the workshops result in decreased looting at sites like Fifa is still under investigation.

CONCLUSIONS ABOUT RESPONDING TO HOLES

The creation of holes as a result of looting is an enduring problem despite decades of responses by governments, law enforcement, NGOs, and archaeologists. Whether the response is training and outreach, law and policy, or archaeological fieldwork, the goal is the same: the protection of Jordanian cultural heritage through a curtailing of archaeological looting. The diverse responses include fences, guards, buy-back programs, site documentation, educational outreach, and community collaboration. New to the standard suite of responses are UAVs, which have a proven track record as powerful tools for documenting excavations, mapping landscapes, and identifying buried features. The LOD project demonstrates that, in tandem with ground truthing and oral interviews and in collaboration with local communities, UAVs can also be used for monitoring ongoing site destruction and threats to endangered landscapes. Four seasons of assessment at Fifa establish that drones can provide reliable, quantifiable evidence for the rate of continuing site damage in contexts where other remote-sensing systems might offer insufficient data. Previous looting at Fifa has taken a heavy toll on the site, and the research of LOD verifies a continuation of the practice, albeit at a reduced pace. Ground truthing and drone data analysis also show significant numbers of undamaged tombs at the site that remain at risk and that are worthy of protection and further study. A comprehensive approach to the landscape, which includes UAV flyovers, ground truthing, oral interviews, and collaborative efforts with the Jordanian DoA and local cultural heritage organizations, is integral to safeguarding and documenting what remains of this Early Bronze Age mortuary site.

Essential to this methodology is, first, an obligation to the people of Jordan and their cultural heritage. The work is not conducted in a landscape devoid of people but includes those who interact with the site daily, weekly, monthly, or yearly. In debates about how to stop or to reduce looting, it is often alleged that local residents do not, and are unable to, care properly for their cultural heritage. The work of the FTP and LOD projects confirms that Jordanians do care and that they are effective custodians when empowered with resources. The demonstrated quantifiable results of the income potential for looters could assist local authorities in creating alternative income supplements or jobs that would replace income from looting.Footnote 63 The LOD project strives to collaborate with local, regional, and national actors in understanding, monitoring, and assessing landscape change at Fifa. The ethical use of drones, which includes a set of safe practices, local engagement, and knowledge sharing, is a growing part of this commitment to doing good for the archaeological record of Jordan.Footnote 64

However, this depiction of the situation at these Early Bronze Age sites on the Dead Sea Plain is incomplete—a hole in the picture in more ways than one. The research is ongoing. More UAV work, archaeological pedestrian surveys, strategic excavations, interviews, local engagement, collaborative efforts with locals, NGOs, and the Jordanian DoA, and interaction with researchers asking similar questions of their landscapes in other parts of the world are all required. In what appears to be the antithesis of archaeological practice, the FTP and LOD projects are working toward filling the holes in the story in order to provide the w(hole) picture of responding to a looted landscape.