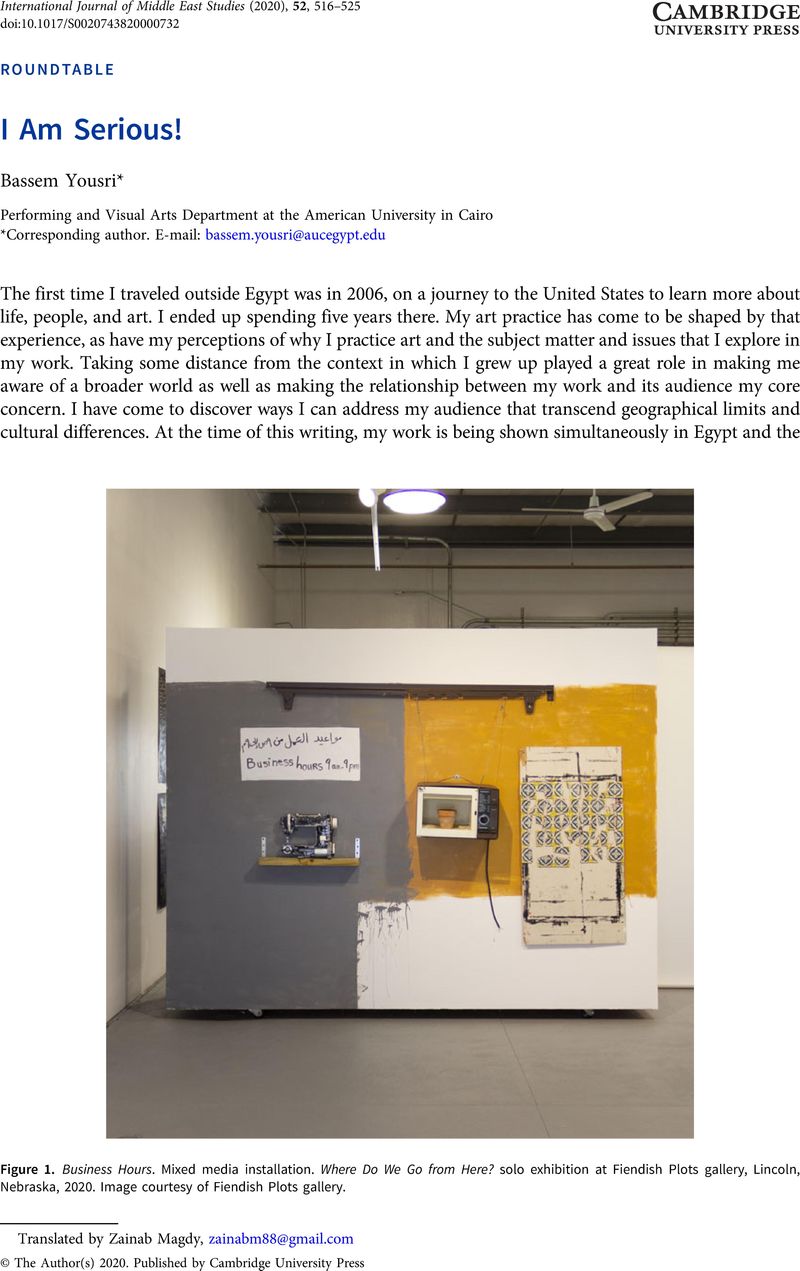

The first time I traveled outside Egypt was in 2006, on a journey to the United States to learn more about life, people, and art. I ended up spending five years there. My art practice has come to be shaped by that experience, as have my perceptions of why I practice art and the subject matter and issues that I explore in my work. Taking some distance from the context in which I grew up played a great role in making me aware of a broader world as well as making the relationship between my work and its audience my core concern. I have come to discover ways I can address my audience that transcend geographical limits and cultural differences. At the time of this writing, my work is being shown simultaneously in Egypt and the United States. Part of a new project that I've called The Art Guide is being shown at Shelter ِِArt Space in Alexandria, Egypt, at the same time that I am showing a different project called Where Do We Go from Here? at Fiendish Plots gallery in Lincoln, Nebraska, in the United States (Fig. 1).

Figure 1. Business Hours. Mixed media installation. Where Do We Go from Here? solo exhibition at Fiendish Plots gallery, Lincoln, Nebraska, 2020. Image courtesy of Fiendish Plots gallery.

In this text, I explore several stops along my career from 2007 to the present. I will not describe these stops chronologically but rather in a sequence that better reflects the evolution of my artistic language over the years and the reasons for this progression. This is not an attempt to write an academic essay in which I try to connect my works with theory or specialized writings; it is more of a personal attempt to examine some of the experiences and events across the span of several years that have necessarily played a part in reshaping my art practice and the choices I make when expressing and representing my ideas.

The Art Guide, January 2020

It always gives me pleasure to make a friend laugh or smile. This thought has inspired one of my latest projects, which I have developed during several artist residencies since 2016. Can I create a conceptual art piece that manifests itself as a joke and would make its viewer burst out laughing rather than feel intimidated by it? What gives an art piece value or worth and what strips it of this, deeming it worthless? Is art that takes on a serious tone more valuable than art that is predominantly humorous?

When I visit an exhibition, I do not look at the works on display as an artist; rather, I form my opinions as a recipient or a member of the audience. I have always pondered the problematic relationship between audiences (especially in Egypt) and art exhibitions in general, especially when it comes to conceptual art. Except for those who work there, museums of modern art have no visitors, and contemporary art spaces are only visited by the same small circle of artists and those interested in the cultural scene or those who work in it. Add to this the assertion I repeatedly hear from many who are not visual arts specialists that they cannot understand the works they see and therefore cannot formulate an opinion about them. They presume that the shown works are “good” but that they lack the required experience to understand them. They might even go so far as to assume that they are less intelligent than the shown work and the artist who created it, since certainly the visual artist has depicted some deep concept, and to understand it the viewer needs to match the artist's depth.

Personally, I do not prefer works that presume cleverness or project a sense of being above the viewer formally or culturally. I realize that this generalization is somewhat obscure; perhaps what I am referring to are works that are difficult to decode and interact with even if you read the accompanying texts. Such a text may be written in a style or jargon that is alienating and complicated to the point that even those who work in the arts find it difficult to understand. I am not interested in creating art only for curators and art specialists. On the contrary, I seek to create art that speaks to the largest audience possible, even if I may not always be successful in such endeavours.

All of these concerns and ideas have led me to a project in which I make works that explain themselves to the audience. And so the “Art Guide” was born: a cartoon-like character who plays the role of my alter ego and explains the works that I have created using various methods and mediums (Fig. 2). Through this character, I try to create a platform that allows me a great deal of freedom to experiment with diverse mediums and art forms; a platform that allows me to experiment to the extent of creating art that goes against my personal taste, as long as the Art Guide comments on them. In the context of the Art Guide, I sometimes try to conceptually impersonate other artists and to formulate concepts and create works using methods that are unfamiliar to me. Through this process, I can present the same concept from various angles simultaneously, and maybe then I can reach a deeper level of objectivity and a deeper understanding of multiple creative processes.

Figure 2. Reality Is a Construction. “Here, ladies and gentlemen, the artist invites us to reconsider our understanding of reality. Could it be a construct of our own imagination?” Wood, glass, photographic prints on archival matte paper, acrylic paint. Figure 60 x 48 cm, speech bubble 68 x 46 cm, right panel 98 x 53 cm, center panel 130 x 113 cm, left panel 98 x 53 cm. Magic Window group exhibition, Shelter Art Space, Alexandria, Egypt, 2020. Image courtesy of the artist.

Tyler School of Art, Philadelphia, Fall 2007

“When I look at these works, I don't see where you come from in them!” said Odili Odita, the Nigerian American artist who was one of my professors at Tyler School of Art and Architecture at Temple University, where I did my MFA. Odita said this to me during his visit to my studio close to the end of the first semester I spent at Tyler. At that time, I had started rebelling against traditional methods in search of my singular voice and for an answer to the question of why I make art in the first place. I was trying to move away from all influences that connected my art with ancient Egyptian art and the traditional figurative style that I had been taught at the School of Fine Arts in Cairo (Fig. 3). I had started making a group of drawings and oil paintings in which I mixed realistic representation with characters executed in childish and cartoonish form (Fig. 4). The paintings posed philosophical questions related to the general human condition.

Figure 3. The Arrival. Oil on papyrus and carved wood, 64 x 90 cm, 2008. Image courtesy of the artist.

Figure 4. The Creation of Eve from Adam's Rib. Oil on canvas, 175 x 246 cm, 2008. Image courtesy of the artist.

I was surprised by Odili's remark. It made me question whether the US art scene expects an Egyptian artist to make a certain type of art that somehow depicts their “Egyptian-ness.” Every now and then, I hear an echo of his remark; since then, I have been searching for the meaning of my Egyptian-ness both in Egypt and abroad.

Homage to the Egyptian Revolution, March 2011; The Parliament of the Revolution, January 2012

I have always avoided making art that falls into the trap of political propaganda or promotes a certain ideology and always thought of my art practice as a way of starting an open discussion with the widest audience possible. I constantly strive to include my audience in the process of asking questions, rather than offering specific information or opinions that are tightly closed off to the viewers or coming up with rigid statements. However, when I look back at the projects I made during the period around the 25 January Revolution, I find an incredibly direct discourse, and I fear that I may have fallen into the trap I was trying to avoid.

Between 2011 and 2012, I participated with several works in exhibitions in Egypt, the US, Germany, Italy, and the UK. Most of these works reflected direct political messages inspired by the political events I was living through at the time; Homage to the Egyptian Revolution (1 and 2), Cairo Headlines, and The Parliament of the Revolution are a few examples (Figs. 5 and 6). Many curators, institutions, and art festivals were interested at that time in exhibiting the “art of the Arab spring,” putting many young Egyptian artists in the limelight, although over time their presence in the art scene has receded.

Figure 5. Homage to the Egyptian Revolution. Acrylic ink on walls and fired white stoneware figurines. Kansas State University, Kansas, 2011. Image courtesy of the artist.

Figure 6. The Parliament of the Revolution. Mixed media (wall drawing and digital video projection). Shift Delete 30 group exhibition, Saad Zaghloul Center, Cairo, 2012. Image courtesy of the artist.

Maybe the aforementioned works have contributed to documenting this pivotal moment in history. Despite my reservations about their direct discourse, I hope these works presented ideas and concepts that went beyond the events that inspired them. With time and the changing political realities, I continued to create works inspired by and critiquing the political situation, except that now I use a less direct discourse and avoid relying on images that are directly related to the content of daily news reports. I have become more conscious of and more concerned with an artistic practice that takes a “political” stance. To go further, I believe that to continue creating and teaching art during times of political oppression is in itself a form of resistance and an attempt to promote change.

“Are You Addicted to Conflict?” Residency Unlimited, New York City, Summer 2016

A question came from a woman in the audience during a lecture I gave on my work at Residency Unlimited. “Are you addicted to conflict?” she asked. This was in New York City in the summer of 2016. I was with two other artists, both from Lebanon, and the question was addressed to the three of us. The answer given by both of them shocked me; they confirmed that they were indeed addicted to life amid conflict. I found the question astonishing and heavily laden with preconceived notions that the Western world has about life in Arab countries or the Middle East as a whole, since it seemed to automatically assume that Arab artists who make art based on their political reality reside in countries that are seething with conflicts. The question also implied that these artists were addicted to life in such difficult circumstances because without conflict they would not find subject matter for their art. My answer to the question was clear and immediate: “I definitely try to live my life away from any struggles and conflicts, but when you find yourself within one, you have to deal with it.”

I do not necessarily feel that my life in Cairo is a life amid conflict. It is life in a huge city that is full of contradictions. Since I grew up in Cairo, I am accustomed to life under the rule of an autocratic regime that restricts freedom of speech as well as independent artistic movements and spaces, yet I cannot imagine that anyone can be addicted to this. On an ordinary day in Cairo, I do not sit at home lamenting my luck and weeping over my life in this miserable place all day. When I roam the streets of Cairo, I do not find people crying in streets and alleyways all day and night. This is not to repudiate or belittle people's daily struggles to make ends meet or the general sentiment of frustration at the difficult living conditions, the ever-increasing prices, and the regime's autocracy and corruption. I find that describing life in Arab countries as one that is desolate and full of conflict is a superficial portrayal. I have always felt irritated by artworks from the Arab world that adopt a melodramatic tone and present only a desperate image of the lives of our peoples—unfortunately an image that is easily promoted in international festivals and exhibitions.

During the same talk, another attendee asked a question in a somewhat resentful tone: “What then is your role as an artist living in the current political circumstances in Egypt?” From his features and accent, I thought he was probably an Egyptian (or Arab) who had migrated years ago to the United States. I am always perplexed by questions like this, which are usually asked in the context of lectures or talks that I've given or attended outside of Egypt. However, with time, I have come to have a clear stance about these questions. Why, when outside the Middle East, does a large segment of the audience that attends art events featuring works by Arab artists in various fields consider these artists representatives of their people or their generation? What exactly is this role I carry on my shoulders whenever I travel abroad to show my work? My role, as I understand it, is to express my ideas and concerns as genuinely or sincerely as I can. I would like the viewer to smile or laugh when they encounter one of my works and also feel provoked enough by it to ask questions related to the concept it carries. I am not a politician, nor do I work in politics or ever plan to. I am an artist and a thinker who is concerned with the political and economic situation in the context I live in because it affects my daily life. Other things I am concerned with are love, people, our human existence and our relationships with each other, nature, animals, planets, and galaxies, and so forth.

The Wardrobe Man, 2018

On a summer day in 2016, I received an email from Karen Havskov Jensen and Klavs Weiss, who run a small arts organization called ET4U in the West Jutland area in the Danish countryside, inviting me to participate in a compelling project. They were organizing a video art festival, and within the framework of that project they came up with the idea of inviting five artists from different countries and asking each of them to create a video work based on one of the objects in different local museum collections. The invitation was to participate in a game that involved a playful challenge; none of the artists would receive any information related to the museum object assigned to them except a title and each artist would have to do their research on the subject in a short period of three days only. The point of the game was not to commission international artists to make documentary films on the local history of these towns in the Danish countryside but rather to offer the possibility for an artist to come from a very different context and look closely at a context that was foreign to them and reinterpret it. I agreed to playing the game for two reasons; the first was that the idea itself appealed to me, and the second was because of how accustomed we are to researchers and artists from the “First World” doing research and art projects on issues related to “Third World” countries. The opposite rarely happens, cementing the long history of unbalanced power structures between these two entities. I was told that the museum object I was to research was the “Wardrobe Man.” In October of the same year, I traveled to Denmark for three days to do the necessary research and film raw material with the help of the archivist of the Struer Museum, Karin Elkjær, and one of the elders of the town, a former school teacher named Søren Raarup, who knew its history and its tales.

The Wardrobe Man was an interesting and perplexing character; he decided to isolate himself in 1914 and walked around dragging his wardrobe on wheels to settle on the beach of a village called Oddesund where he lived by the sea until he died in 1956.

At the beginning of my research, I assumed he was just an eccentric or someone who had gone mad, and I tried to find facts that would support this assumption. Yet, after looking into his history and speaking to people who actually met him during childhood or early youth, I realized that my assumption was far from true. This confronted me with quite a contradiction. I have always pondered on the idea of isolating myself from the complications of life brought on by social, political, economic, and cultural restraints. I have thought about the possibility of enjoying the experience of existing in and of itself and living at peace without having to give in to the pressures of making a living or fulfilling career aspirations. Despite all this, the moment I was face to face with the story of an individual who achieved this, I jumped to the conclusion that he was either mad or eccentric.

By then, I had decided to make a film about points of similarity between the Wardrobe Man and myself, through which I could also probe the idea of quitting the social context in which one lives (Fig. 7). I started digging into my personal archive while concurrently digging into the history of the Wardrobe Man, planning to present my assumptions about him and the reasons for his chosen isolation.

Figure 7. The Wardrobe Man, film still. Experimental docufiction, 48 minutes, 2018. Image courtesy of the artist.

Guideposts: I am Serious! Sharjah, UAE, 2016

Having been raised in Cairo, since I was young I have been intrigued with the visual culture of clutter that dominates the city. The source of this “clutter” has always preoccupied me, and with time I noticed that this clutter was a main feature of various government institutions and bodies. I began documenting its manifestations in 2012 during the numerous visits I paid to many of these governmental institutions to procure official papers or fulfill similar errands. I have finally reached the conclusion that these government bodies are the source of this perplexing visual phenomenon that extends to the street and manifests itself in a myriad of forms, from official signposts stressing the state's ownership over a piece of land, to other signposts that declare a checkpoint on the highway (Figs. 8 and 9) or a sculpture in public spaces that the state has commissioned “artists” to make, a few of which became quite famous on social media and were the subject of ridicule. An example of this is a crudely rendered replica of Queen Nefertiti's bust that was placed, in 2015, in the Minya governorate which is where the original bust was found. Later on, I came up with a name for this phenomenon, the “Institutional Aesthetic,” which is marked by a complete disregard for the visual effect, as long as the object fulfills the function for which it was originally created. The Institutional Aesthetic naturally extends to the daily practices of the Egyptian people and is manifested in some haphazardly made-up solutions for any and all types of problems. For example, securing a parking spot for a car in front of a shop by way of placing various objects to occupy that space, or placing a worn-out piece of wood as a sign stating “Closed for Prayer” by one of the shops, and so on and so forth.

Figure 8. Border Guards. Checkpoint near the entrance/exit of Sinai. Image courtesy of the artist.

Figure 9. State Property, Cairo Municipality. Sign near al-Arafa neighborhood in Cairo. Image courtesy of the artist.

Does this phenomenon reflect a certain philosophy or approach to management? Does its effect go beyond the obvious contradictions between the authority of the state as an entity and its visual means of expression and communication?

I decided in 2016 to begin a series of sculptural pieces under the title Guideposts that adopt this aesthetic, and to investigate this culture of clutter and visual chaos by removing it from its original context and putting it under the spotlight (Fig. 10). The works that belong to this ongoing project generally address the audience with a written statement or instructions expressed as particular orders that are in contrast with the chaotic appearance of the work itself (Fig. 11). In doing so, I want to methodically examine the relationship between the authority that the work attempts to maintain over the audience and the reactions of this audience.

Figure 10. I Am Serious! Mixed media installation, 9 x 4.5 m, Sharjah, UAE. Commissioned by Sharjah Art Foundation, 2016. Image courtesy of the artist.

Figure 11. Trash Goes Here. Mixed media installation. Where Do We Go from Here? solo exhibition at Fiendish Plots gallery, Lincoln, Nebraska, 2020. Image courtesy of Fiendish Plots gallery.

The Guideposts project is an extension of a work I created in 2013 entitled The Official Institution. The last solo exhibition I created (in January 2020) at Fiendish Plots in Lincoln, Nebraska, Where Do We Go from Here?, can also be considered an extension to this project.

When corruption has become a visual aesthetic so embedded in our everyday details, where do we go from there? When xenophobia and bigotry have become the new face of major governments around the world, where do we go from there? It is also a question I ask myself after finishing any new project or a large body of work. Where do I go from here?

Bassem Yousri is a visual artist, filmmaker, and art educator. His work has been exhibited nationally and internationally including at the Museum of the Moving Image (MoMI) in New York, USA; Centre Pompidou in Paris, France; Sharjah Art Foundation, UAE; and Mathaf: the Arab Museum of Modern Art in Doha, Qatar.