No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

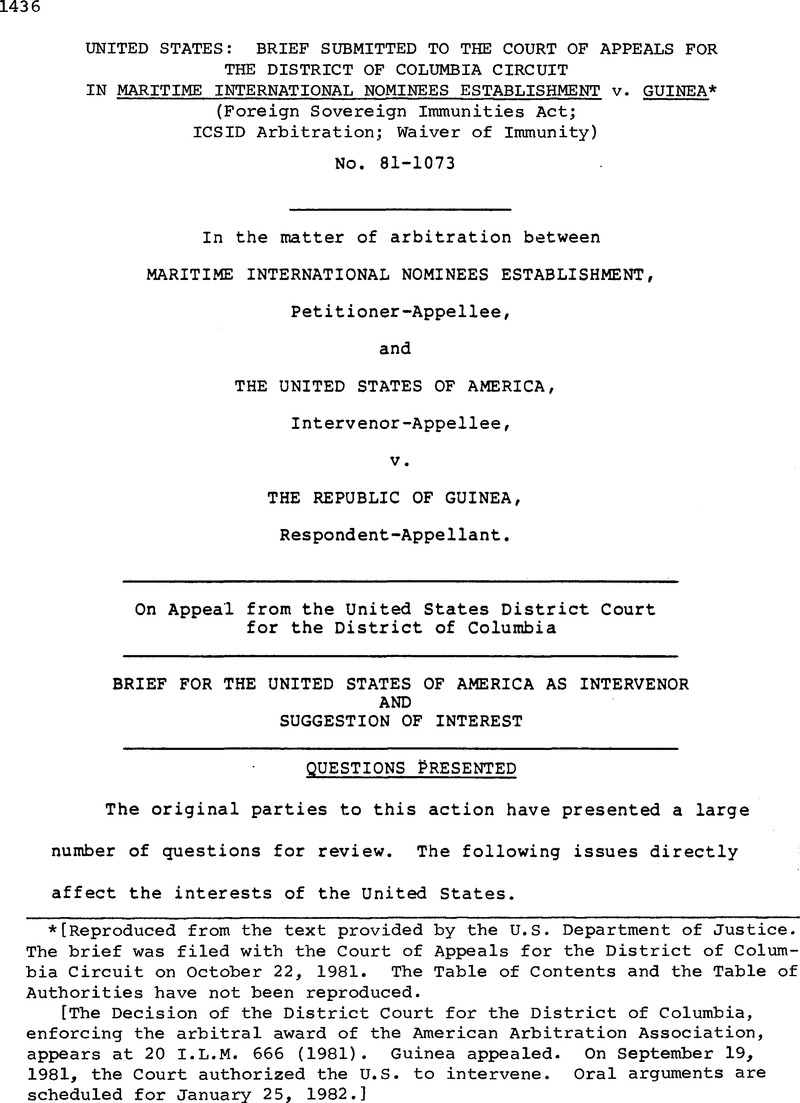

United States: Brief Submitted to the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit in Maritime International Nominees Establishment V. Guinea*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 March 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1981

Footnotes

[Reproduced from the text provided by the U.S. Department of Justice. The brief was filed with the Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit on October 22, 1981. The Table of Contents and the Table of Authorities have not been reproduced.

[The Decision of the District Court for the District of Columbia, enforcing the arbitral award of the American Arbitration Association, appears at 20 I.L.M. 666 (1981). Guinea appealed. On September 19, 1981, the Court authorized the U.S. to intervene. Oral arguments arescheduled for January 25, 1982.]

References

1/ The committee report issued by the House of Representatives is identical to the one issued by theSenate. Compare, H.R. Rep. No. 94-1487, 94th Cong;., 2d Sess.(1976) with S. Rep. No. 94-1310, 94th Cong., 2d Sess.(1976). To avoid duplication, this brief cites only the House Report. [15 I.L.M. 1398 (1976)]

2/ In Fandel, this Court held that diplomatic activities donot constitute contacts with the forum under the long-arm statute for the District of Columbia. The long-arm provisions of the FSIA were patterned on that statute. H.R.Rep. No. 94-1487, 94th Cong., 2d Sess. 13 (1976).

3/ On one occasion, the House Report to the FSIA describes sovereign immunity as an “affirmative defense,” suggesting that it only enters the case at the behest of the defendant. H. Rpt. at 17. The inquiry required by § 1330, however, makes it clear that the assertion of jurisdiction over a foreign state must rest upon a consideration of the immunity issue. This interpretation of the Act is confirmed by the provision concerning default judgments. In default situations, sovereign immunity remains in issue despite the absence of the foreign state altogether. 28 U.S.C. § 1608(e). See H. Rpt. at 25-26. International Assoiationof Machinists v. OPEC, 649 F.2d 1354, 1356 (9th Cir. 1981);Ipitrade International, S.A. v. Federal Republic of Nigeria, 465 F. Supp. 824, 827 (D.D.C. 1978).

4/ In this connection, it bears noting that the Verlinden court reached its decision without benefit of briefing on any of the critical questions. Neither party to the appeal challenged the application of 28 U.S.C. § 1330 to suits brought by alien plaintiffs; and, although the constitutionality of a federal statute was decided, the court did not notify the Attorney General or provide him with an opportunity to intervene in support of the statute. Contra 28 U.S.C. § 2403(a).

5/ The sovereign immunity of foreign governments differs in this respect from the sovereign immunity of the United States. The latter doctrine rests, at least in part, upon the notion that the courts, as creatures of the sovereign,lack the power to assert jurisdiction over their creator without its express consent.

5/ The Verlinden court erred in suggesting that most commercial cases brought pursuant to the FSIA will begoverned by the law of the state in which the suit was filed. 647 F.2d at 326. In fact, most international legal contracts specify what law will apply in the event of a dispute. Verlinden and Nigeria specified that disputes would be resolved in accordance with the Uniform Customs and Practice of Documentary Credits. Contrary to the suggestion of the court of appeals, that document does not form part of the law of the State of New York. Id. It is a brochure published by the International Chamber of Commerce in Paris and it represents the body of private international law established by the major international banks for dealing with the problems that arise in connection with the use of international letters of credit.

6/ The Centre may be moved by a two-thirds vote of ICSID's governing body, The Administrative Council. ICSID Convention, Art. 2.

7/ ICSID maintains a list of potential arbitratorsdesignated by contracting states and the President of the World Bank. ICSID Convention, Articles 12-16. Actualpanels, however, need not be drawn exclusively from thislist. ZA., Art. 40. Similarly, ICSID's Administrative Council has promulgated rules of procedure which govern ICSID proceedings unless the parties specify alternative procedures. Id., Art. 6; ICSID Regulations and Rules,ICSID/4/Rev. 1. [7 I.L.M. 351 (1968)]

8/ The enforcement of ICSID awards is thus on an entirelyseparate footing from awards within the frame work of eitherthe Federal Arbitration Act, 9 U.S.C. §§ 1-14, or the Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of ForeignArbitral Awards, [1958] 21 U.S.T. 2517, T.I.A.S. 6997; 9U.S.C. §§ 201-208.

9/ By agreement, however, the parties may provide for amodification of this rule of exclusivity. See ICSID Convention, Art. 26 (exhaustion of local remedies as aprerequisite to ICSID); Amerasinghe, 5 J. MAR. L. & COM. at234 (provisional measures by national courts pending conclusion of ICSID proceedings.)

10/ Because parties may mutually agree to forego the ICSID process, the abstention rule proposed would arise intwo contexts: where both parties appear before the court,but present reasonably differing views on whether ICSID isavailable to adjudicate their dispute; and, where the only party appearing argues that ICSID is unavailable, but thepleadings reflect that there is a non-trivial question as to whether the case comes within ICSID's exclusive jurisdiction.

11/ Such claims may be raised through diplomatic channels,see Declaration of Lannon Walker, appended to Suggestion ofInterest of the United States of America in Support of Appellant's Motion for Stay without Bond, or pursuant to the Convention's provision for mandatory jurisdiction before the International Court of Justice. See ICSID Convention, Art.64.

12/ This interpretation is supported by the text of thecourt's opinion, particularly its reference to the ICSID rules, see 595 F. Supp. at 143, and by the court's commentsin the hearing preceding its ruling, see Hearing on Motions(January 8, 1981), Civil Action No. 78-388 at 17-18, 23-24[excerpts attached as appendix to this brief].

13/ MINE argues that the court's finding of waiver was based exclusively on the original contract and codicilbetween the parties (rather than the subsequent consent form), and argues that those documents did not contemplate an arbitration under ICSID auspices. See Brief for Appellee at20-23. The United States takes no position on either ofthese contentions; its sole interest is to apprise this courtof its view that, where there is an agreement contemplating arbitration through ICSID, that agreement should not be used to infer a waiver of sovereign immunity except for purposes of enforcing an ICSID award.