No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

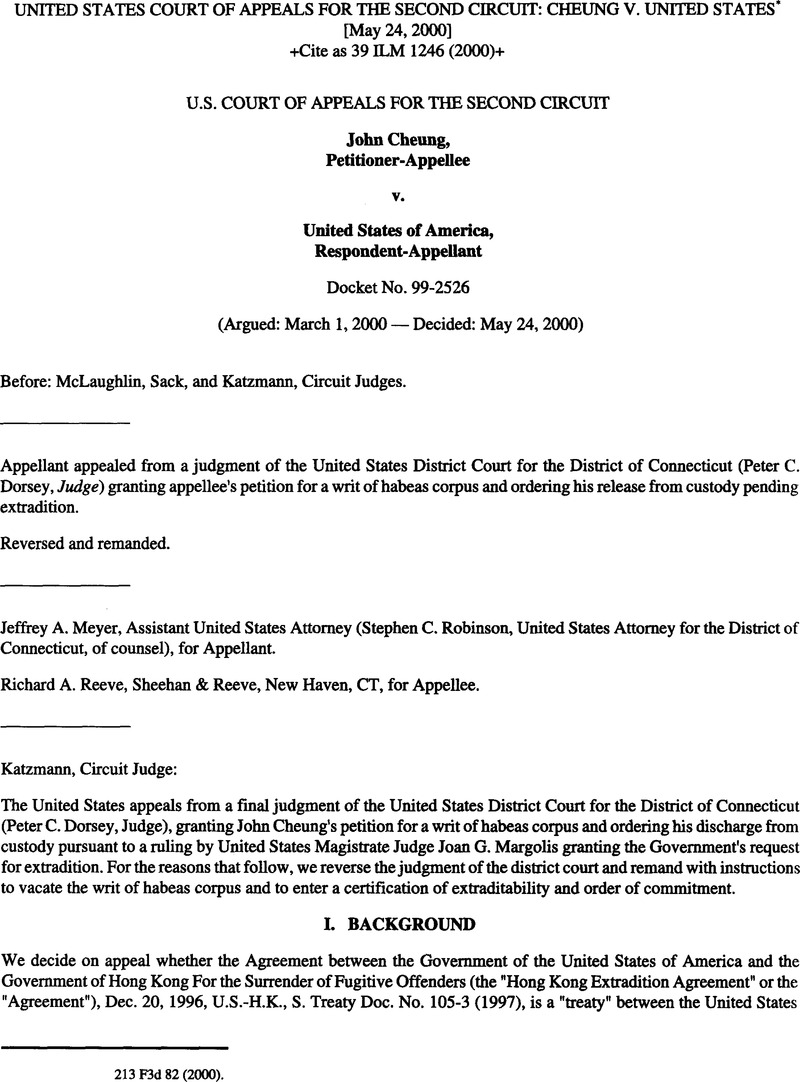

United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit: Cheung v. United States*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © 2000

Footnotes

213 F3d 82 (2000).

References

Endnotes

* 38 ILM 450 (1999) — ILM Editor

1 As used in this opinion, “Hong Kong” refers to the physical territory comprising three areas: Hong Kong Island, the Kowloon Peninsula, and the New Territories (an area comprising 92 percent of the total terrain of the three areas).

2 In Cheung I, decided before Hong Kong's return to Chinese rule, the magistrate judge granted a prior request for Cheung's extradition. Id., 968 F. Supp. at 809. Subsequently, on July IS, 1997, without objection by the Government, the district court granted Cheung's petition for a writ of habeas corpus in light of Hong Kong's reversion. The present case commenced upon the Government's filing of a second complaint for extradition, dated June 24,1998.

3 In 1948, as part of an overall recodification of title 18 of the United States Code, §3181 was amended. Prior to the 1948 amendments, this section read: The provisions of this Title relating to the surrender of persons who have committed crimes in foreign countries shall continue in force during the existence of any treaty of extradition with any foreign government, and no longer. R.S. § 5275, reprinted in H.R. Rep. No. 80-304, at 242 (1948) (emphasis added). The recodification changed “Title” to “chapter” and “any foreign government, and no longer” to “such foreign government.” 18 U.S.C. § 3181. The legislative history of the amendment makes clear that it resulted in only “[m]inor changes … in phraseology.” H.R. Rep. No. 80-304, at 158 (1948).

4 The courts in Rossi, McCullough, and Blanco sought to reconcile a later statute with a pre-existing treaty, whereas in the present case, we seek to reconcile an earlier statute as it applies to a subsequent treaty.

5 Although the statement referred to the treaties with France and England, the object of the extradition law could not have been limited to then-existing treaties because the United States had, by 1848, begun negotiations with, among others, Mexico, Prussia, Belgium, and Austria. See Moore, supra,§ 74, at 84.

6 The Committee Report explained that the document was termed an “agreement” rather than a “treaty” and used the word “surrender“ rather than “extradite” at the request of the PRC, but referred to these as “semantic preferences” only. S. Exec. Rep. No. 105- 2, at 11.

7 In recommending the Agreement to the full Senate, the Committee explained that the Agreement had been authorized by the PRC. See S. Exec. Rep. No. 105-2, at 8. This fact was also noted by the President in his Letter of Submittal, see S. Treaty Doc. No. 105-3, at v, and is incorporated into the preamble to the Agreement. The PRC's approval of the Agreement is, however, of no moment to our interpretation of the extradition statute. Whatever significance the political branches of our Government may have attached to the PRC's endorsement, that is a political issue that is constitutionally committed to them.