No CrossRef data available.

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 May 2017

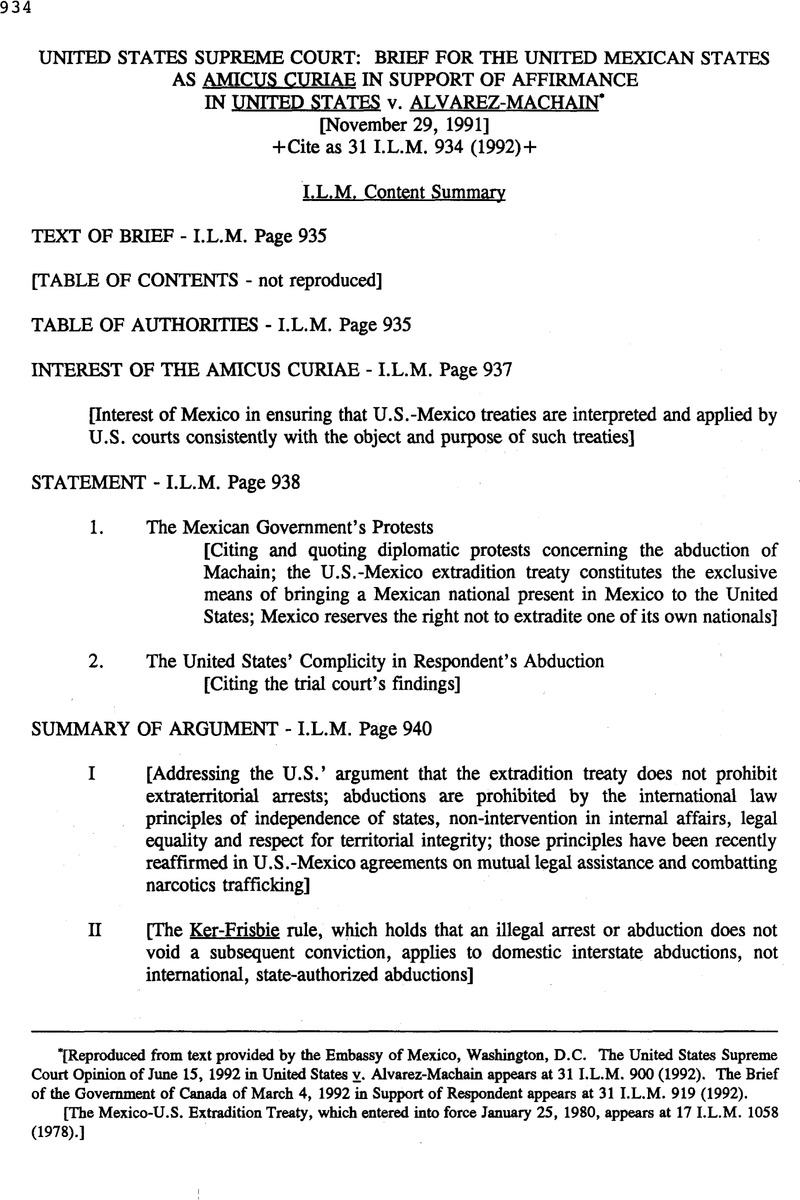

[Reproduced from text provided by the Embassy of Mexico, Washington, D.C. The United States Supreme Court Opinion of June 15, 1992 in United States v. Alvarez-Machain appears at 31 I.L.M. 900 (1992). The Brief of the Government of Canada of March 4, 1992 in Support of Respondent appears at 31 I.L.M. 919 (1992).

[The Mexico-U.S. Extradition Treaty, which entered into force January 25, 1980, appears at 17 I.L.M. 1058 (1978).]

1 Extradition Treaty between the United States of America and the United Mexican States with Appendix, done in Mexico May 4, 1978, entered into force January 25, 1980, 31 U.S.T. 5059, T.I.A.S. No. 9656, registered by the United States in the United Nations Treaty Series as U.N.T.S. 19462 on December 9, 1980, pursuant to Article 102 of the Charter of the United Nations; reprinted in J.A. 72-87.

2 59 Stat. 1031, T.S. No. 993.

3 2 U.S.T. 2394, T.I.A.S. No. 2361, 119 U.N.T.S. 3, as amended by the Protocol of Buenos Aires of February 27, 1967, 21 U.S.T. 607, T.I.A.S. No. 6847.

4 See Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, May 23, 1969, Art. 31, reprinted in 63 Am.J.Int’l L. 875, 885 (1969):

5 The precursors of the current extradition treaty between Mexico and the United States are the treaty of May 20, 1862, 12 Stat. 1199, T.S. No. 209 (terminated January 24, 1899), and the treaty of April 22, 1899, 31 Stat. 1818, T.S. No. 242, with supplements of 1903, 1926 and 1941 (terminated January 25, 1980).

6 Art. 14 of the “Ley de Extradición Internacional” of December 22, 1975, provides: No Mexican shall be extradited to a foreign state except in exceptional cases in the discretion of the Executive. (Informal translation.)

7 Exec. Rep. M, Extradition Treaty with the United Mexican States, 96th Cong., 1st Sess. VI (1979) (Letter of Submittal by Secretary of State Cyrus Vance).

8 The Mexican Political Constitution provides in relevant part: Article 14. … No person shall be deprived of life, liberty, property, possessions, or rights without a trial before a previously established court in which the essential formalities of procedure are observed in accordance with laws in effect prior to the act. In criminal cases no penalty shall be imposed by mere analogy on convincing rationale but rather must be based on a law which is in precisely applicable to the crime in question…. Article 16. No one shall be disturbed in his person, family, domicile, documents or possessions except by virtue of a written order by the competent authority stating the legal grounds and justification for the action taken. No order of arrest or detention shall be issued against any person other than by the competent judicial authority, unless such arrest or detention is preceded by a charge, accusation, or complaint concerning a specific act pun¬ishable by physical punishment, made by a credible party, supported by a sworn affidavit or by other evidence indicating the probable guilt of the accused;…

9 Mexican municipal law makes no distinction between “self-executing” treaties and those that merely constitute a contract between States, as known in United States law. Article 133 of the Mexican Political Constitution provides: This Constitution, the laws of the congress of the Union which emanate therefrom, and all treaties made, or which shall be made in accordance therewith by the President of the Republic, with the approval of the Senate, shall be the Supreme Law throughout the Union. The judges of each State shall conform to the said Constitution, the law, and treaties, notwithstanding any contradictory provisions that may appear in the Constitution or laws of the States. A treaty that has been approved by the Mexican Senate and proclaimed by the President forms part of the municipal law of Mexico and confers personal rights on individuals that are enforceable in Mexican courts.

10 Article 3 of the treaty provides in relevant part: Evidence Required Extradition shall be granted only if the evidence be found sufficient, according to the laws of the requested Party,… to justify the committal for trial of the person sought if the offense of which he has been accused had been committed in that place….

11 Article 16 of the Mexican Extradition Law requires that the Mexican authorities be furnished: The formal extradition request and the documents on which it is based by the requesting State must include: Specification of the crime for which the extradition is sought. Proof that the crime has been committed and the probable involvement of the accused. If the accused has been convicted by the courts of the requesting state, it will suffice to submit an authenticated copy of the final judgment. A copy of the legal provisions of the requesting State, with regard to the definition of the crime and the punishment, and the corresponding statute of limitations, as well as an authorized statement of the fact that said provisions and statute were in force at the time the crime was committed. The original warrant of arrest which may have been issued against the accused.

12 The treaties described in the text provide a “relevant rule of [conventional] international law” that governs the relations between Mexico and the United States within the purview of Art. 31(3) of the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, supra, n.4.

13 Treaty of Cooperation Between the United States of America and the United Mexican States for Mutual Legal Assistance, done in Mexico City December 9, 1987, entered into force for the United States May 3, 1991, T.I.A.S. No., reprinted in 27 I.L.M. 443 (1988).

14 Agreement between the United States of America and the United Mexican States on Cooperation in Combatting Narcotics Trafficking and Drug Dependency, done in Mexico City February 23, 1989, entered into force July 30, 1990, T.I.A.S. N, reprinted in 29 I.L.M. 58 (1990).

15 United Nations Convention Against Illicit Traffic in Narcotic Drugs and Psychotropic Substances, done at Vienna December 20, 1988, entered into force for the United States and for Mexico on November 11, 1990, T.I.A.S. No, reprinted in 28 I.L.M. 493 (1989).

16 119 U.S. 436 (1886).

17 The additional historical facts, not recorded in the Court's opinion, are taken from Fairman, Ker v. Illinois Revisited, 47 Am.J.Int'l L. 678 (1953).

18 It was less than three decades ago, in Banco National de Cuba v. Sabbatino, 376 U.S. 398 (1984), that the Court squarely ruled that international law is federal law, and that state courts must follow the federal lead in ascertaining, interpreting and applying that body of law.“[R]ules of international law should not be left to divergent and perhaps parochial state interpretations.” Id. at 425.

19 Aside from the provisions of the extradition treaty, under international law Mexico has the primary right to place him on trial, both under principles of territoriality and nationality.

20 E.g., United States v. Lira, 515 F.2d 68, 70-71 (2d Cir. 1975).

21 E.g., United States v. Toro, 840 F.2d 1221, 1229 (5th Cir. 1988); see also Verdugo-Urquidez, supra, 939 F.2d at 1353 n. 12 (citing cases).

22 E.g., United States v. Yunis, 924 F.2d 1086 (D.C. Cir. 1991).

23 E.g., Matta-Ballesteros v. Henman, 896 F.2d 255, 260 (7th Cir.), cert, denied, U.S. (1990); see also Verdugo-Urquidez, supra, 939 F.2d at 1349 n. 9 and 1353 n. 12. (citing cases).

24 Mexican authorities commenced a criminal investigation in 1985 into the kidnaping and murder of DEA agent Enrique Camarena Salazar and Alfredo Zavala Avelar. Warrants of arrest were issued for Rafael Caro Quintero, Ernesto Fonseca Carrillo, and others in the state of Jalisco (Guadalajara) on charges of illegal deprivation of freedom in the form of abduction, homicide, and various narcotics offenses. They were charged with the offenses named on September 19, 1989, and were tried and convicted on December 12, 1989. The court imposed the maximum penalty on both defendants, viz., 40 years imprisonment, various fines and forfeiture of properties. The convictions were affirmed on appeal on August 10, 1990, by the Third District Criminal Court of the State of Jalisco. Nine of their principal associates were also convicted and sentenced for their complicity in the offenses. In addition, Caro Quintero, Fonseca Carrillo and twenty-one of their associates were convicted and sentenced in the Federal District (Mexico City) for narcotics offenses, firearms offenses, criminal association and illegal deprivation of freedom offenses. In that case, Caro Quintero was sentenced to a separate 34-year prison term and Fonseca Carrillo was sentenced to a separate 11-1/2 year term. Their twenty-one associates received sentences ranging from 12-1/2 to 14-1/4 years, plus fines and forfeitures. A third person, believed to be a principal in the Camarena case, Miguel Angel Felix Gallardo, has also been arrested and is being tried, together with nine of his associates in the Federal District (Mexico City) on various narcotics trafficking, firearms and bribery charges. They have been in custody since April 1989.

25 The Reporter and the Assistant Reporter of the project were Prof. Edwin D. Dickinson and Prof. William W. Bishop, Jr., respectively. The advisory panel on the project consisted of a veritable Who's Who of American international law scholars and practitioners at the time: Judge Learned Hand; George W. Wickersham, former Attorney General of the United States; Elihu Root, former Secretary of State; Manley 0. Hudson, former judge of the Permanent Court of International Justice and a member of the Permanent Court of Arbitration; Green H. Hackworth, Legal Adviser of the Department of State; Charles Chaney Hyde and James Brown Scott, former Solicitors of the Department of State; Philip C. Jessup, a future American judge on the International Court of Justice.

26 The United States' reliance on The Ship Richmond v. United States, 9 Cranch (13 U.S.) 102 (1815) (Pet. Br. at 14 n.8) is misplaced. The holding of that case cannot be reconciled with this Court's decisions, supra. and Richmand must, be regarded as having been overruled.