No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

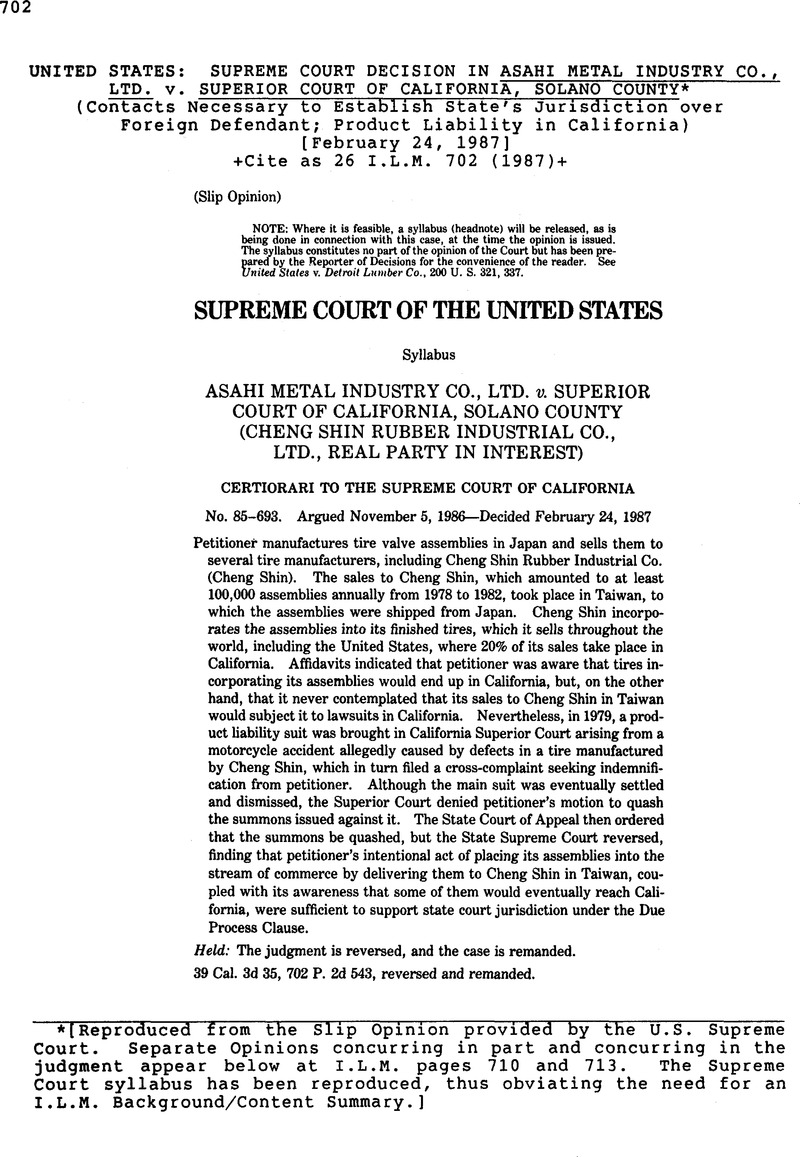

United States: Supreme Court Decision in Asahi Metal Industry co. Ltd. V. Superior Court of California, Solano County (Contacts Necessary to Establish State's Jurisdiction Over Foreign Defendant; Product Liability in California)

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1987

Footnotes

[Reproduced from the Slip Opinion provided by the U.S. Supreme Court. Separate Opinions concurring in part and concurring in the judgment appear below at I.L.M. pages 710 and 713. The Supreme Court syllabus has been reproduced, thus obviating the need for an I.L.M. Background/Content Summary.]

References

* We have no occasion here to determine whether Congress could, consistent with the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment, authorize federal court personal jurisdiction over alien defendants based on the aggregate of national contacts, rather than on the contacts between the defendant and the State in which the federal court sits. See Max Daet-wyler Corp. v.R. Meyer, 762 F. 2d 290, 293-295 (CA3 1985); Dejames v. Magnificence Carriers, Inc.,654 F.2d 280, 283 (CA3 1981); see also Born, Reflections on Judicial Jurisdiction in International Cases, to be published in 17 Ga.J. Intfl,Comp. L. 1 (1987); Lilly, Jurisdiction Over Domestic and Alien Defendants, 69 Va.L. Rev.85, 127-145 (1983).

1 See, e. g., Bean Dredging Corp. v. Dredge Technology Corp., 744 F. 2d 1081 (CA5 1984); Hedrick v. Daiko Shoji Co., 715 F. 2d 1355(CA9 1983); Nelson by Carson v. Park Industries, Inc., 717 F. 2d 1120, 1126 (CA7 1983), cert, denied, 465 U.S. 1024 (1984); Stabilisierungsfonds Fur Wein v. Kaiser Stuhl Wine Distributors Pty. Ltd., 207 U. S. App. D. C. 375, 378, 647 F.2d 200, 203 (1981); Poyner v. Erma Werke Gmbh, 618 F.2d 1186, 1190-1191 (CA6),cert,denied,449 U.S.841 (1980); cf. Fidelity and Casualty Co. of New York v. Philadelphia Resins Corp.,766 F.2d 440 (CA10 1985) (endorsing stream-of-commerce theory but finding it inappli cable in instant case), cert, denied,U.S.(1986); Montalbano v. Easco Hand Tools,Inc.,766 F.2d 737 (CA2 1985)(noting potential applicability of stream-of-commerce theory, but remanding for further factual findings). See generally Currie, The Growth of the Long-Arm: Eight Years of Extended Jurisdiction in illinois, 1963 U.111. Law Forum 533, 546-560 (approving and tracing development of the stream-of-commerce theory); C. Wright A.Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure: Civil§ 1069, pp. 259-261 (1969)(recommending in effect a stream-of-commerce approach); von Mehren & Trautman, Jurisdiction to Adjudicate: A Sug-gested Analysis, 79 Harv. L. Rev. 1121, 1168-1172 (1966) (same).

2 The Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit appears to be the only Circuit Court to have expressly adopted a narrow construction of the stream-of-commerce theory analogous to the one the plurality articulates today, although the Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit has implic itly adopted it. See Humble v. Toyota Motor Co., Ltd., 727 F.2d 709 (CA8 1984); Banton Industries, Inc. v. Dimatic Die Tool Co.,801 F.2d 1283 (CAll 1986). Two other Courts of Appeals have found the theory inapplicable when only a single sale occurred in the forum State, but do not appear committed to the interpretation of the theory that the Court adopts today. E.g.Chung v. Nan A Development Corp., 783 F.2d 1124(CA4) cert, denied,U.S.(1986); Dalmau Rodriguez v. Hughes Air craft Co., 781 F. 2d 9 (CA11986). Similarly, the Court of Appeals for the Third Circuit has not interpreted the theory as the plurality has today, but has rejected stream-of-commerce arguments for jurisdiction when the rela tionship between the distributor and the defendant “remains in dispute“ and “evidence indicating that [defendant] could anticipate either use of its product or litigation in [the forum State] is totally lacking,” Max Daetwyler Corp.y. R. Meyer,762 F. 2d 290,298,300, n.13, cert, denied,U.S.(1985), and when the defendant's product was not sold in the forum State and defendant “did not take advantage of an indirect marketing scheme,” De James v. Magnificence Carriers, Inc.,654 F. 2d 280, 285,cert,denied, 454 U.S.1085 (1981).

3 In dissent, I argued that the distinction was without constitutional significance, because in my view the foreseeability that a customer would use a product in a distant State was a sufficient basis for jurisdiction. 444 U.S., at 306-307, and 11,12. See also id.,at 315 (Marshall,J.,dissenting)(“I cannot agree that jurisdiction is necessarily lacking if the product enters the State not through the channels of distribution but in the course of its intended use by the consumer“); id., at 318-319 (Blackmun, J., dissenting)(“foreseeable use in another State seems to me little different from foreseeable resale in another State“). But I do not read the deci Foreign Investment, of September 30, 1986, this prior authorization was obviated; Gaceta Ordinar ia No.33,968 of October 2, 198.

4 Moreover, the Court found that “at least 18 percent of the tubes sold in a particular California motorcycle supply shop contained Asahi valve assemblies,“ App. to Pet. for Cert. C-ll, n. 5, and that Asahi had on ongoing business relationship with Cheng Shin involving average annual sales of hundreds of thousands of valve assemblies, id.,at C-2.