No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

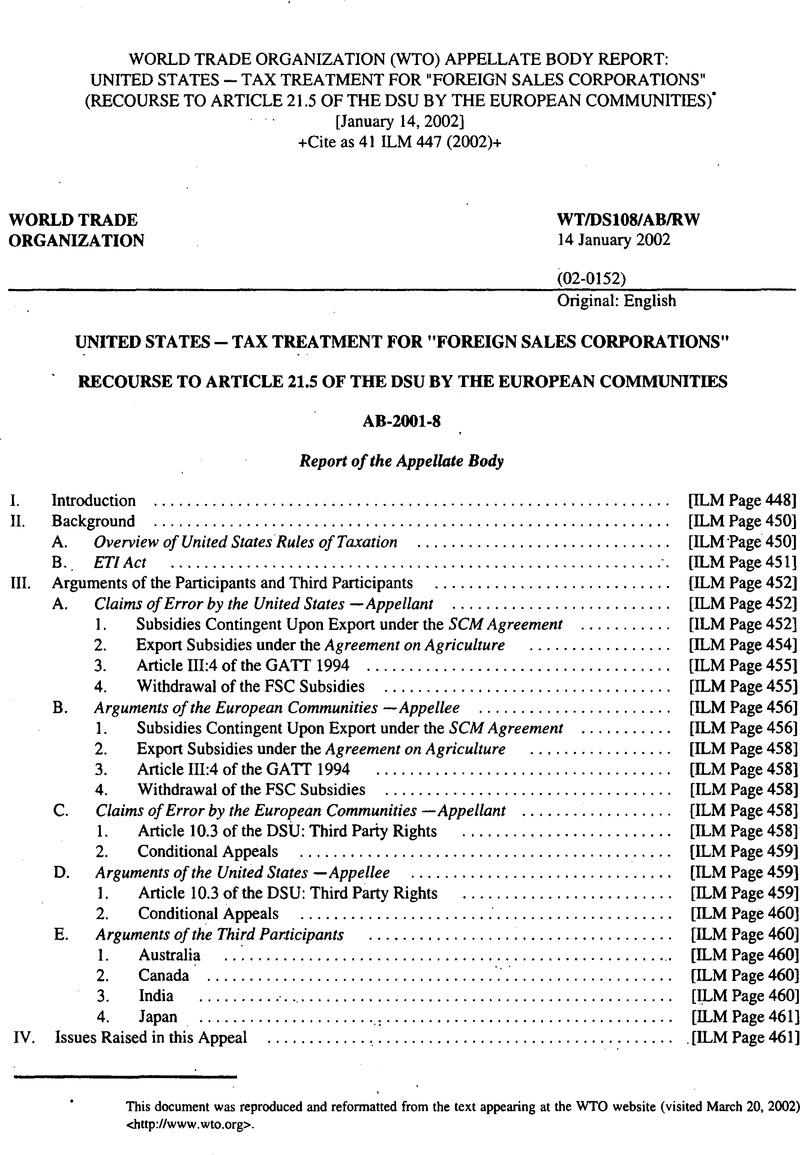

World Trade Organization (WTO) Appellate Body Report: United States - Tax Treatment for “Foreign Sales Corporations” (Recourse to Article 21.5 of the DSU by the European Communities)

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright ©American Society of International Law 2002

References

Endnotes

* This document was reproduced and reformatted from the text appearing at the WTO website (visited March 20, 2002) http://www.wto.org.

1 WT/DS108/RW, 20 August 2001.

2 United States Public Law 106-519, 114 Stat. 2423 (2000).

3 The recommendations and rulings of the DSB resulted from the adoption, by the DSB, of the Appellate Body Report in US —FSC, WT/DS 108/AB/R, adopted 20 March 2000 (the “original Appellate Body Report“). In this Report, we refer to the panel that considered the original complaint brought by the European Communities as the “original panel” and to its report as the “original panel report”.

4 Original Panel Report,US — FSC, WT/DS 108/R, adopted 20 March 2000, as modified by the Appellate Body Report,WT/DS 108/AB/R, para. 8.1.

5 Ibid., para. 8.8.

6 WT/DSB/M/90, paras. 6-7. See also Panel Report, para. 1.3.

7 Panel Report, para. 1.5.

8 Ibid., paras. 1.1-1.13.

9 WT/DS 108/16, 8 December 2000.

10 WT/DS108/19, 5 January 2001.

11 Panel Report, para. 9.1.

12 Ibid., para. 9.2.

13 WT/DS 108/21, 15 October 2001.

14 In its letter, the United States explained that, due to the delivery of the bacterium anthrax to the United States Congress, several buildings had been temporarily closed, including buildings housing the offices of United States Senate officials with jurisdiction over the issues arising in this appeal.

15 Pursuant to Rule 21(1) of the Working Procedures.

16 Pursuant to Rule 23(1) of the Working Procedures.

17 Pursuant to Rules 22 and 23(3) of the Working Procedures.

18 Pursuant to Rule 24 of the Working Procedures.

19 Pursuant to Rule 28(1) of the Working Procedures.

20 Pursuant to Rule 28(2) of the Working Procedures.

21 Appellate Body Report, supra, footnote 3, paras. 6-7.

22 Section 901 (a) IRC.

23 Section 1 relates to the short title of the ETI Act, while Section 4 sets forth a number of “technical and conforming” amendments.

24 Subpart C of part III of Subchapter N of chapter 1, consisting of Sections 921 -927 IRC.

25 Section 3 of the ETI Act, Section 943(e) IRC.

26 Under the ETI Act, the need to satisfy these three conditions is subject to a number of exceptions. We examine certain of these exceptions below, to the extent that they are pertinent to our analysis of the issues on appeal.

27 The detailed rules of the ETI measure provide that foreign trading gross receipts may be earned through (i) any sale, exchange, or other disposition of qualifying foreign trade property; (ii) any lease or rental of qualifying foreign trade property; (iii) any services which are related and subsidiary to (i) and (ii); (iv) for engineering or architectural services for construction projects located (or proposed for location) outside the United States; and (v) for the performance of managerial services for a person other than a related person in furtherance of activities under (i), (ii) or (iii). (Section 3 of the ETI Act, Section 942(a) IRC) We will generally refer to sale and lease transactions as a shorthand reference to the transactions described in (i) and (ii) of this footnote.

28 Section 3 of the ETI Act, Section 943(a)(l) IRC. Section 943(a)(3) and (4) IRC set forth specific exclusions from this general definition.

29 Section 3 of the ETI Act, Section 942(b) IRC.

30 The relevant activities are: (i) advertising and sales promotion; (ii) processing of customer orders and arranging for delivery; (iii) transportation outside the United States in connection with delivery to the customer; (iv) determination and transmittal of final invoice or statement of account or the receipt of payment; and (v) assumption of credit risk. A taxpayer will be treated as having satisfied the foreign economic process requirement when at least 50 percent of the total costs attributable to such activities is attributable to activities performed outside the United States, or, for at least two of these five categories of activity, when at least 85 percent of the total costs attributable to such category of activity is attributable to activities performed outside the United States. (Section 3 of the ETI Act, Section 942(b)(2)(A)(ii), (b)(2)(B) and (b)(3) IRC).

31 Foreign sales and leasing income is defined in Section 941 (c)( 1) IRC.

32 Foreign trading gross receipts are defined in Section 942(a) IRC.

33 Foreign trade income is defined in Section 941(b) IRC.

34 United States’ appellant's submission, para. 107.

35 United States'additional written memorandum, p. 1.

36 Ibid., p. 3.

37 Subject to the anti-abuse rules contained in Subpart F of the IRC. (United States’ additional written memorandum, p. 2)

38 United States’ appellant's submission, para. 142.

39 United States’ appellant's submission, para. 173.

40 Appellate Body Report, WTYDS26/AB/R, WT/DS48/AB/R, adopted 13 February 1998, DSR 1998:1, 135.

41 United States’ appellant's submission, para. 253.

42 Ibid., para. 256.

43 Panel Report, WT/DS139/R, WT/DS142/R, adopted 19 June 2000, as modified by the Appellate Body Report, WT/DS139/AB/R, WT7DS142/AB/R.

44 Appellate Body Report, WT/DS161/AB/R, WT/DS169/AB/R, adopted 10 January 2001.

45 Panel Report, para. 8.23.

46 Panel Report, para. 8.25.

47 Appellate Body Report, WT/DS27/AB/R, adopted 25 September 1997, DSR 1997:11, 591.

48 European Communities’ first submission to the Panel, para. 119; Panel Report, p. A-23.

49 Ibid., para. 158;p.A-29.

50 Ibid., paras. 183-184; p. A-34.

51 Ibid., para. 246; p. A-44.

52 Done at Vienna, 23 May 1969,1155 U.N.T.S. 331; 8 International Legal Materials 679.

53 European Communities’ other appellant's submission, para. 4.

54 European Communities’ second submission to the Panel, para. 160; Panel Report, p. C-30.

55 European Communities’ response to Question 35 posed by the Panel, para. 101; Panel Report, p. F-17.

56 Panel Report, supra, footnote 43; Appellate Body Report, WT/DS139/AB/R, WT/DS142/AB/R, adopted 19 June 2000.

57 Panel Report, para. 8.96.

58 Panel Report, para. 8.43. (footnote omitted)

59 We observe that the United States does not appeal the Panel's finding, in paragraph 8.48 of the Panel Report, that the financial contribution it found to exist under Article l.l(a)(l)(ii) of the SCM Agreement confers a “benefit” within the meaning of Article 1.1 of that Agreement.

60 United States’ appellant's submission, para. 71. See also United States’ additional written memorandum, p. 4.

61 United States’ additional written memorandum, p. 2.

62 Appellate Body Report, WT/DS70/AB/RW, adopted 4 August 2000, para. 47.

63 Supra, footnote 3, para. 90.

64 Appellate Body Report, supra, footnote 3, para. 90.

65 Appellate Body Report, supra, footnote 3, para. 91.

66 We recognize that a Member may have several rules for taxing comparable income in different ways. For instance, one portion of a domestic corporation's foreign-source income may not be subject to tax in any circumstances; another portion of.such income may always be subject to tax; while a third portion may be subject to tax in some circumstances. In such a situation, the outcome of the dispute would depend on which aspect of the rules of taxation was challenged and on a detailed examination of the relationship between the different rules of taxation. The examination under Article 1.1 (a)( 1 )(ii) of the SCM Agreement must be sufficiently flexible to adjust to the complexities of a Member's domestic rules of taxation.

67 Section 943(e) IRC. Thus, although the ETI measure applies to foreign corporations, these corporations are deemed for these purposes to be United States corporations and not foreign corporations. In our discussion below, we treat these foreign corporations as United States corporations.

68 Section 942(a)(3) IRC. We have outlined the United States rules of taxation, including the ETI measure, in Section II of this Report.

69 Qualifying foreign trade property is defined in Section 943(a)(l) and (2) IRC, while Section 943(a)(3) and (4) identifies property that is excluded from the definition.

70 The transactions giving rise to income covered by the measure are described in Section 942(a)( 1) IRC. We recall that we refer to sale and lease transactions as a shorthand reference to the “sale, exchange or other disposition” of QFTP, and to the “lease or rental” of this property. See Section 942(a)(l)(A) and (B) IRC.

71 Section 114(e) IRC, read together with Section 942(a) IRC.

72 See infra, paras. 104 and 181 -183.

73 Panel Report, paras. 8.25-8.26.

74 We examine below the merits of the United States’ characterization of QFTI as “foreign-source income”, which the United States is entitled to exempt to avoid double taxation of this income, when we review the Panel's findings regarding footnote 59. See infra, paras. 121-186.

75 We recall that the measure applies to certain foreign corporations that elect to be treated as United States corporations. For the purpose of United States taxation, these corporations are deemed to be United States corporations, (supra, para. 93 and footnote 67 thereto) Thus we do not examine the United States’ fiscal treatment of the foreign-source income of foreign corporations including foreign subsidiaries of United States corporations — that do not elect to be treated as United States corporations. We do not, therefore, examine the rules of taxation for the foreign-source income of foreign subsidiaries of United States corporations. See United States’ appellant's submission, paras. 34-36.

76 Sections 861-865 IRC and 26CFR 1.861-1.865 provide rules to determine whether income of United States citizens and residents is from sources within or outside the United States.

77 Section 901(a) IRC. Such creditable foreign taxes are those listed in Sections 901(b), 902 and 960 IRC, but these tax credits are subject to the limitation set forth in Section 904. See also the applicable Federal Regulations in 26 CFR 1.901-1.902, 1.904 and 1.960.

78 Section 904(a) IRC. We understand this provision to mean that if foreign-source income makes up, for instance, 10 percent of the total taxable income, the amount of the tax credit cannot exceed 10 percent of the total tax due. The amount of the foreign-source income is determined by applying the source rules contained in Sections 861-865 IRC and 26 CFR 1.861-1.865.

79 See J. Isenbergh, International Taxation – U.S. Taxation of Foreign Persons and Foreign Income, 2nd ed., (Aspen Law & Business, 1999), Vol. II, para. 30:4, p. 55:2, who states “[t]his limitation [in Section 904(a)] seeks to confine the credit to the U.S. tax attributable to foreign source income.”

80 We mentioned earlier that, where a taxpayer elects to use the ETI measure, it must give up any tax credits it has obtained through taxation in a foreign State that is attributable to the income excluded from taxation. Accordingly, the measure will be beneficial to taxpayers where the amount of tax otherwise due on excluded QFTI is greater than the amount of tax credits which the taxpayer must give up in relation to the excluded QFTI. For instance, this calculus is likely to result in taxpayers electing to use the measure where: (a) the amount of income actually taxed in a foreign jurisdiction is less than the amount of excluded QFTI and (b) where the rate of taxation applied to income taxed in a foreign jurisdiction is lower than the United States rate of taxation that would "otherwise" be applied to the excluded QFTI.

81 European Communities' first submission to the Panel, paras. 104-120; Panel Report, pp. A-21-A-23. The European Communities also argued, in the alternative, that both the basic and the extended subsidies provided under the ETI Act are de facto export contingent. See European Communities' first submission to the Panel, paras. 131-145; Panel Report, pp. A-25-A-28; European Communities' response to Question 2 posed by the Panel, para. 6-11; Panel Report, p. F-3.

82 Panel Report, para. 8.75.

83 Panel Report, para. 8.60.

84 Ibid., para. 8.163. The European Communities filed a conditional appeal relating to the Panel’s failure to examine the “extended” subsidy, which we will come to below, (infra, paras. 253–255) 85United States’ appellant’s submission, paras. 164 and 169.

86 Appellate Body Report, Canada – Measures Affecting the Export of Civilian Aircraft (“Canada –Aircraft”), WT/DS70/AB/R, adopted 20 August 1999, paras. 162–180; Appellate Body Report, US – FSCsupra, footnote 3, paras. 96-121; Appellate Body Report, Canada –Autos, supra, footnote 56, paras. 95–117; Appellate Body Report, Canada – Aircraft (Article 21.5 – Brazil), supra, footnote 62, paras. 25–52. 87Appellate Body Report, supra, footnote 86, para. 166.

88 Appellate Body Report, supra, footnote 56, para. 100.

89 Although Section 943(a)(l)(A) IRC applies to property “manufactured, produced, grown, or extracted within or outside the UnitedStates”, we will refer to property “produced” within or outside the United States as a shorthand reference.

90 Section 943(a)(l)(B) IRC. (emphasis added)

91 United States’ response to questioning at the oral hearing.

92 Under the FSC measure, qualifying property had to be produced in the United States by a person other than an FSC, and it had to be held primarily for sale, lease, or rental, in the ordinary course of trade or business by, or to, an FSC for direct use, consumption, or disposition outside the United States. (Section 927(a)(1)(A) and (B), now repealed by the ETI Act) Under Section 943(a)(1)(B), inserted into the IRC by Section 3 of the ETI Act, a United States citizen or resident producing property within the United States must hold this property “primarily for sale, lease, or rental, in the ordinary course of trade or business outside the United States.” Thus, the only difference between the provisions at issue in the original proceedings and those at issue in these proceedings, relating to property produced in the United States, is that the FSC measure provided that the FSC could not produce the qualifying property, but that it had to be the seller or lessor, whereas the ETI measure does not state who must produce the qualifying property or who must sell it. This difference between the provisions has no bearing on the export contingency of the respective measures.

93 We recall that the European Communities makes a conditional appeal of the Panel's exercise of judicial economy with respect to its claim concerning property produced outside the United States. We address this conditional appeal below. See infra, paras. 253-255.

94 Supra, paras. 108-109.

95 We note that the European Communities makes a conditional appeal concerning the Panel's exercise of judicial economy in relation to this issue. See infra, paras. 253-255.

96 Panel Report, para. 8.90 and footnote 188 thereto, (footnote omitted)

97 Ibid., para. 8.93.

98 Ibid., para. 8.95. (footnote omitted)

99 Ibid.

100 Ibid.

101 Panel Report, paras. 8.107 and 9.1(a).

102 United States’ appellant's submission, para. 207.

103 Ibid., para. 204.

104 Ibid., para. 218.

105 Ibid., paras. 187-188.

106 Ibid., para. 194. See also Panel Report, footnote 197 to para. 8.95.

107 United States’ appellant's submission, para. 209.

108 Appellate Body Report, United States —Measure Affecting Imports of Woven Wool Shirts and Blouses from India (” US — Wool Shirts and Blouses“), WT/DS33/AB/R and Corr. 1, adopted 23 May 1997, DSR 1997:1, 323, at 335.

109 Ibid., at 337.

110 Appellate Body Report, supra, footnote 40, para. 104.

111 Appellate Body Report, US —FSC, supra, footnote 3, para. 93. (emphasis omitted)

112 Appellate Body Report, supra, footnote 3, para. 101.

113 Shorter Oxford English Dictionary, C. T. Onions (ed.) (Guild Publishing, 1983), Vol. II, p. 2057.

114 Ibid., Vol. I, p. 788.

115 Panel Report, para. 8.93.

116 See Appellate Body Report, Japan — Taxes on Alcoholic Beverages (“Japan — Alcoholic Beverages II “), WT/DS8/AB/R, WT/DS10/AB/R, WT/DS11/AB/R, adopted 1 November 1996, DSR 1996:1, 97, at 110; Appellate Body Report, Chile — Taxes on Alcoholic Beverages, WT/DS87/AB/R, WT/DS110/AB/R, adopted 12 January 2000, paras. 59-60; and Appellate Body Report, US — FSC, supra, footnote 3, para. 90.

117 Panel Report, para. 8.93.

118 Department of the Treasury, Internal Revenue Service, Publication 901 (Rev. April 2001), Cat. No. 46849F.

119 Two commonly used model tax conventions are the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (“O.E.C.D.“) Model Tax Convention on Income and Capital (“O.E.C.D. Model Tax Convention“) and the United Nations Double Taxation Convention between Developed and Developing Countries (“U.N. Model Tax Convention“), which contain similar provisions. The majority of bilateral treaties adopt the principles of these two model tax conventions, with many also adopting their detailed provisions (See B. J. Arnold & M. J. Mclntyre, International Tax Primer (Kluwer Law International, 1995), p. 100 and A. H. Qureshi, The Public International Law of Taxation (Graham & Trotman, 1994), p. 371). According to the O.E.C.D., there are close to 350 treaties between O.E.C.D. Members and over 1500 treaties world-wide which are based on the O.E.C.D. Model Tax Convention (O.E.C.D. website, www.oecd.org; 2001). The member States of the Andean Community (Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela) adopted a model tax agreement among themselves, which is to be used when member States conclude bilateral taxation treaties with third States (Decision 40 of 8 November 1971 of the Andean Group, Annex II, Standard Agreement to Avoid Double Taxation between Member Countries and Other States Outside the Subregion (Convenio Tipo para evitar la doble tributacidn entre los Paises Miembros y otros Estados ajenos a la Subregion) (“Andean Community Model Tax Agreement“).

120 The member States of the Andean Community (Bolivia, Colombia, Ecuador, Peru and Venezuela) adopted an agreement among themselves to address double taxation (Decision 40 of 8 November 1971 of the Andean Group approving the Agreement to Avoid Double Taxation between Member Countries (Convenio para evitar la doble tributacidn entre los Poises Miembros) ;“Andean Community Agreement“). (www.comunidadandina.org/normativa/dec/d040.htm and www.comunidadandina.org/ingles/treaties/dec/d040e.htm) This agreement entered into force on 1 January 1981. 11 member States of the Caribbean Community (Antigua and Barbuda, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, Saint Kitts and Nevis, Saint Lucia, Saint Vincent and the Grenadines, and Trinidad and Tobago) also adopted an agreement on double taxation among themselves on 6 July 1994 (Agreement Among the Governments of the Member States of the Caribbean Community for the Avoidance of Double Taxation and the Prevention of Fiscal Evasion with Respect to Taxes on Income, Profits or Gains and Capital Gains and for the Encouragement of Regional Trade and Investment) ;“Caricom Agreement“), (www.Caricom.org under “Information Services” and “Treaties and Protocols“)

121 We observe that, before the Panel, the United States provided examples of the source rules applied by Brazil, Canada, Chile, Malaysia, Panama, Saudi Arabia, Taiwan, the United Kingdom and the United States. The widely recognized principles of taxation appear to be reflected in these domestic rules of taxation. (United States’ second submission to the Panel, para. 62; Panel Report, p. C-69; Exhibits US-24-US-29 submitted by the United States to the Panel; United States’ response to Question 12 posed by the Panel, paras. 27-29; Panel Report, pp. F-38 and F-39)

122 For instance, some States will tax a non-resident only on business income generated by a permanent establishment on its territory. In that respect, we observe that the O.E.C.D. Model Tax Convention allows a State to impose tax on business profits generated by a non¬ resident through a “permanent establishment” situated on its .territory. Article 5.1 of the Convention defines a “permanent establishment” as a “fixed place of business through which the business of an enterprise is wholly or partly carried on.” This definition requires a relatively strong link with the “foreign” State before it may tax a non-resident. However, Article 5.5 of the Convention adds that a permanent establishment may exist where a person, other than die taxpayer, “habitually exercises … an authority to conclude contracts” for the taxpayer. The O.E.C.D. Model Tax Convention itself, therefore, admits of differing standards to determine whether business income was generated by activities linked to the territory of a “foreign” State. However, we also observe that some States will tax a non-resident on the basis of activities of a less permanent character provided there is nonetheless a sufficient connection between the activities generating the income and the territory of the taxing State. The United States, for instance, taxes the business income of non-residents if the income is “effectively connected” with a trade or business conducted in the United States. (Sections 871(b) and 882(b) IRC) The United States cites examples of other States which it considers tax non-residents on income generated through a trade or business conducted in that State, without the creation of a permanent establishment (see supra, footnote 121).

123 We note that the Andean Community Agreement, the Caricom Agreement, and the Andean Community Model Tax Agreement and the O.E.C.D. and U.N. Model Tax Conventions describe a variety of situations in which a “foreign” State is entitled to tax a non-resident on income generated through activities which are linked to that State. The nature of the links required depends on the nature of the income. Articles 7 of the Andean Community Agreement and of the Andean Community Model Tax Agreement provide that business profits are taxable only in the State where these profits are “obtained” through business activities conducted in that State. Article 8 of the Caricom Agreement states that business profits are taxable only in the State where the business activities generating these profits are “undertaken”. Thus, a non-resident will be taxed on business profits generated through activities undertaken in a “foreign” State. Articles 7 of the O.E.C.D. and U.N. Model Tax Conventions provide that “business” income of a non-resident, generated through a “permanent establishment”, may be taxed in the State where the permanent establishment is located see supra, footnote 122). Articles 5 and 12 of the Andean Community Agreement and the Andean Community Model Tax Agreement, Articles 6 and 7.2(i) of the Caricom Agreement, and Articles 6 and 13 of the O.E.C.D. and U.N. Model Tax Conventions state that income, or capital gains, derived by a non-resident from immovable property, or from its alienation, are taxable in the “foreign” State where the property is situated. Articles 8 of the O.E.C.D. and U.N. Model Tax Conventions provide that income generated from the “operation of ships or aircraft in international traffic” may be taxed in a “foreign” State if the “place of effective management” of the non-resident enterprise is situated in that State. Article 8 of the Andean Community Agreement and Article 9.1 of the Caricom Agreement allow only the State of residence of the enterprise to tax such “international” income. However, Article 9.2 of the Caricom Agreement provides that where the transport activities take place exclusively within the territory of one of the member States, that State shall tax the income, irrespective of the place of residence of the enterprise. Article 8 of the Andean Community Model Tax Agreement is similar to Article 8 of the Andean Community Agreement, while the alternative Article 8 of the Andean Community Model Tax Agreement, allows a State to tax transport activities that take place in that State, irrespective of the place of residence of the enterprise. Articles 13 of the Andean Community Agreement and of the Andean Community Model Tax Agreement, and Articles 15 of the Caricom Agreement and of the O.E.C.D. and U.N. Model Tax Conventions, indicate that the employment income of a non-resident may be taxed in a “foreign” State if the services are rendered or if the employment is exercised in that State. According to Article 17 of the Caricom Agreement, and Articles 16 of the O.E.C.D. and U.N. Model Tax Conventions, the fees of a non-resident director may be taxed in the “foreign” State if the corporation of which the person is a director is resident in that State. Under Article 14 of the Andean Community Agreement and of the Andean Community Model Tax Agreement, professional services provided by an enterprise may be taxed in a “foreign” State if the services are performed there. Under Articles 16 of the Andean Community Agreement and of the Andean Community Model Tax Agreement, Article 18 of the Caricom Agreement, and Articles 17 of the O.E.C.D. and U.N. Model Tax Conventions, the income of an entertainer derived from “activities” exercised in a “foreign” State may be taxed in that State. Thus, in the case of each type of income addressed by these agreements and conventions, a “foreign” State may tax a non-resident only on income which is generated by activities which are linked to or connected with the territory of that State.

124 United States’ additional written memorandum, p. 2.

125 Ibid.

126 We note that Isenbergh states that “the concept of source is not infinitely malleable. If only for practical reasons, some connection with a country is required to justify treating income as being from sources within that country.” (emphasis added) Isenbergh also states that “commercial or industrial countries regard income as deriving its source from specific economic activity conducted within them, whereas many developing countries … focus on whose pocket income is paid from.” (emphasis added) (J. Isenbergh, supra, footnote 79, Vol. I, para. 5.1, p. 5:2)

127 See, for” instance, Articles 23A of the O.E.C.D. and U.N. Model Tax Conventions. Among bilateral tax treaties, See, for instance, Article 22(l)(a) of the Agreement between the Federal Republic of Germany and the Islamic Republic of Pakistan for Avoidance of Double Taxation in the Area of Taxes on Income (Abkommen zwischen der Bundesrepublik Deutschland und der Islamischen Republik Pakistan zur Vermeidung der Doppelbesteuerung aufdem Gebiet der Steuern vom Einkommen), 14 July 1994, Bundesteuerblatt 1995 I p. 617, Bundesgesetzblatt 1995 II p. 836; Article 22(2)(a) of the Double Taxation Agreement between Mauritius and Madagascar ;Convention entre le Gouvemement de la Re∼publique de Maurice et le Gouvernement de la Ripublique de Madagascar tendant a iviter les doubles impositions et la prevention de I'Evasion fiscale en matiere d'impdts sur le revenu), 30 August 1994; and Article 24(b)(l) of the Double Taxation Agreement between the Republic of France and the United Kingdom (Convention entre la France et le Royaume-Uni de Grande-Bretagne et d'Irlande du Nord tendant a iviter les doubles impositions et a privenir VEvasion fiscale en matiere d'impdts sur les revenus), 22 May 1968, Journal Officiel de la Ripublique franqaise, 24 November 1969, p. 11476, as amended. See also A. H. Qureshi, supra, footnote 119, p. 370; B. J. Arnold & M. J. Mclntyre, supra, footnote 119, pp. 40-43; J. Schuch, “The Methods for the Elimination of Double Taxation in a Multilateral Tax Treaty”, in M. Lang et al. (eds.), Multilateral Tax Treaties, New Developments in International Tax Law (Kluwer Law International and Lindeverlagwien, 1998), pp. 129-152; and M. Pires, International Juridical Double Taxation of Income (Kluwer Law and Taxation, 1989), pp. 173-184.

128 Panel Report, para. 8.95; United States’ appellant's submission, paras. 216-220.

129 United States’ appellant's submission, para. 194, quoting the United States’ Senate Report on the FSC Repeal and Extraterritorial Income Exclusion Act (“Senate Report“), S. Rep. No. 106-416 (2000), Exhibit US-2 submitted by the United States to the Panel, pp. 2 and 6; United States’ House of Representatives Report on the FSC and Repeal and Extraterritorial Income Exclusion Act (“House Report“), H.R. Rep. No. 106-845 (2000), Exhibit US-3 submitted by the United States to the Panel, pp. 10 and 13.

130 Panel Report, footnote 197 to para. 8.95 quoting House Report, p. 19.

131 See infra, paras. 175-177, where we address the exception to this requirement in Section 942(c)(l) IRC.

132 Sections 942(b)(2)(A)(ii) and 942(b)(3) IRC. As an alternative, the foreign economic process requirement may be satisfied where the costs attributable to activities performed outside the United States account for at least 85 percent of the costs in two of the five categories mentioned in paragraph 152. See Section 942(b)(2)(B) IRC.

133 We note that Isenbergh states that, in the case of sale of goods by a producer, the income generated by the sales transaction is attributable to “easily distinguishable activities” which are “often combined”, namely “production and sale” activities. Isenbergh indicates that in an international sales transaction, these production and sales activities may take place “in different countries.” These activities, therefore, generate income that has different sources which are “compounded” unless the income from the different sources is separated. Isenbergh states that “ideally” the different “elements of the transaction” would be “disengaged” using arm's length pricing rules. The manufacturer would be treated as if it had sold the goods to an independent distributor at arm's length prices, who in turn resold the goods. This would “dissect” the transaction on the basis of the place where the different activities occurred. (J. Isenbergh, supra, footnote 79, Vol. I, para. 10.9, p. 10:16)

134 Section 941(a)(l)(C) IRC.

135 Section 941(a)(l)(B) IRC. We note that, under Section 941(a)(l)(A) IRC, QFTI may be 30 percent of the “foreign sales and leasing income” of the taxpayer. We will examine this formula below. See infra, paras. 172-178.

136 At the oral hearing, the United States referred to the formulae for calculating the amount of QFTI as “rules of thumb.“

137 House Report, p. 20. The figures used in these examples are also based on the example given in the United States’ House Report.

138 United States’ response to questioning at the oral hearing.

139 The United States confirmed our understanding at the oral hearing.

140 See supra, para. 25, for a description of the formulae used to calculate the amount of QFTI.

141 Where the taxpayer elects to use the 1.2 percent rule to calculate the tax exemption with respect to any transaction, Section 941 (a)(3) IRC confines the exemption to the income earned in that single transaction. Any income earned in any other transaction, relating to the same property, cannot benefit from an exemption, even in the case of a second transaction between related parties. This provision, therefore, effectively excludes the application of the deeming rule for related parties in Section 942(b)(4) IRC, which allows income from more than one transaction to be included in the calculation of QFTI. See supra, paras. 159 and 163.

142 See supra, paras. 25 and 156.

143 See supra, para. 159.

144 We acknowledge that, for certain purposes, related parties may be treated as a single economy entity. Yet, the application of the deeming rule here adds another situation where the ETI measure misallocates domestic- and foreign-source income.

145 This method of determining FSLI does not apply to income derived from the “lease or rental” of QFTP. We examine below the calculation of FSLI in transactions involving the “lease or rental” of QFTP. See infra, paras. 170-174.

146 We note that under Section 941(c)(3)(B) IRC, only “directly allocable expenses” are to be “taken in account in computing foreign trade income for purposes of FSLI. (emphasis added)

147 Senate Report, p. 10; House Report p. 2 (emphasis added)

148 Section 941 (c)( 1 )(B) IRC.

149 See supra, paras. 155 and 166.

150 Senate Report, p. 11; House Report, p. 24.

151 We note that Isenbergh considers that the use of arm's length pricing is an appropriate method for separating manufacturing income from sales income. (J. Isenbergh, supra, footnote 79, Vol. I, para. 10.9, p. 10:16) See also supra, footnote 133.

152 We note that a taxpayer with no more than $5,000,000 of declared foreign trading gross receipts may have other gross receipts which are not declared as foreign trading gross receipts.

153 Clearly, where the transaction involves the production of QFTP outside the United States, there would be other foreign links than the use outside the United States. We deal here with the United States’ argument as it relates to property produced within the United States.

154 Senate Report, p. 19; House Report, p. 33.

155 26CFR1.924(a)-lT-(d).

156 See supra, para. 100.

157 We recall that, under Section 114(d) IRC, a taxpayer gives up tax credits attributable to income excluded from taxation under the ETI measure.

158 See supra, para. 104 and footnote 80 thereto.

159 See supra, para. 170, examining the rule that, where QFTI is calculated as 30 percent of FSLI, FSLI is the income “properly allocable“ to certain foreign activities, other than in the case of “lease or rental” income.

160 See supra, paras. 175-177, examining the exemption granted to certain taxpayers without satisfaction of the foreign economic process requirement and, paras. 178-180, examining the exemption granted for service-related income where the services are performed in the United States.

161 See supra, paras. 156-168, examining the rules whereby QFTI may be calculated either as 1.2 percent of total foreign trading gross receipts or as 15 percent of total foreign trading income.

162 In addition, under the third formula for FSLI, there are circumstances where the ETI measure could grant a tax exemption for lease or rental income which includes domestic-source income. See supra, para. 173.

163 Panel Report, para. 8.122.

164 Panel Report, para. 8.116.

165 United States’ appellant's submission, paras. 247-248.

166 Appellate Body Report, US — FSC, supra, footnote 3, para. 138

167 Ibid., para. 139.

168 Appellate Body Report, US— FSC, supra, footnote 3, para. 140.

169 Ibid., paras. 141-142.

170 We note that the United States has not appealed any other aspect of the Panel's finding under Article 10.1 of the Agreement on Agriculture. In particular, the United States has not appealed the Panel's finding that it was appropriate to examine the European Communities’ primary claim under Article 10.1 of the Agreement on Agriculture, without first examining its alternative claim under Article 9.1 of that Agreement. (Panel Report, para. 8.112 and footnote 219 thereto) Nor has the United States appealed the Panel's finding that the measure is “applied in a manner which results in, or which threatens to lead to, circumvention of export subsidy commitments” within the meaning of Article 10.1. (Panel Report, paras. 8.117-8.120) We note that the United States did not contest either of these issues before the Panel. (Panel Report, para. 8.112 and footnote 219 thereto; Panel Report, para. 8.121; and United States' first submission to the Panel, paras. 220-221; Panel Report, p. A-100)

171 See supra, para. 21. See also infra, para. 201, for the text of Section 943(a)(l)(Q IRC of the fair market value rule.

172 Panel Report, para. 8.158.

173 Ibid., para. 8.135.

174 Ibid, para. 8.149.

175 Ibid, para. 8.158.

176 We refer to this provision as the “fair market value rule“; the Panel termed it the “foreign articles/labour limitation.“

177 Appellate Body Report, Japan —Alcoholic Beverages II, supra, footnote 116, at 109-110, quoting from Panel Report, United States —Section 337 of the Tariff Act of 1930, adopted 7 November 1989, BISD 36S/345, para. 5.10. We cited this statement in Appellate Body Report, European Communities — Measures Affecting Asbestos and Asbestos-Containing Products ;“EC — Asbestos “), WT/DS135/AB/R, adopted 5 April 2001, para. 97, a dispute that also involved Article III:4 of the GATT 1994.

178 Appellate Body Report, EC —Asbestos, supra, footnote 177, para. 98.

179 United States’ appellant's submission, paras. 254-256.

180 Article 1:1 of the GATS provides that “[t]his Agreement applies to measures by Members affecting trade in services.” (emphasis added)

181 Appellate Body Report, supra, footnote 47, para. 220. We made the same statement regarding the word “affecting” in Article 1:1 of the GATS in our Report in Canada —Autos, supra, footnote 56, para. 150.

182 See United States’ first submission to the Panel, para. 201; Panel Report,..pp. A-95-A-96. The United States confirmed our understanding of the fair market value rule in its response to questioning at the oral hearing.

183 Appellate Body Report, Korea —VariousMeasures on Beef, supra, footnote 44, para. 142.

184 Appellate Body Report, Japan —Alcoholic Beverages II, supra, footnote 116, at 110.

185 We recall that the tax exemption may be:. 1.2 percent of foreign trading gross receipts; 15 percent of foreign trade income; or 30 percent of foreign sales and leasing income. See supra, para. 25.

186 See supra, para. 201, for the text of the fair market value rule. See also Panel Report, para. 8.133.

187 We note that the European Communities provided the Panel with a list of circumstances, for illustrative purposes, where such a requirement to use like domestic products may arise. (Annex to the European Communities’ second submission to the Panel; Panel Report, pp. C-46-C-52)

188 Panel Report, para. 8.170.

189 Appellate Body Report, supra, footnote 3, para. 177(a).

190 Original Panel Report, supra, footnote 4, para. 8.8.

191 WT/DS108/11,2 October 2000. See ato WT/DSB/M/90, paras. 6-7.

192 Appellate Body Report, supra, footnote 86, para. 45.

193 Section 5(b)( 1) of the ETI Act.

194 Section 5(c)(l)(A)of the ETI Act.

195 See Section 5(c)(l)(B)(ii) of the ETI Act.

196 Panel Report, para. 8.169.

197 Appellate Body Report, Brazil —Aircraft (Article 21.5 — Canada), supra, footnote 86, para. 46.

198 Ibid., para. 45.

199 Panel Report, para. 6.1; European Communities’ first submission to the Panel, paras. 247-258 and 260; Panel Report, pp. A-44-A-45.

200 Panel Report, para. 6.2. (footnote omitted)

201 Ibid., para. 6.3, subpara.2.

202 Panel Report, para. 6.3, subpara. 11.

203 By way of background, we note that the European Communities has, as a third party in four unrelated proceedings under Article 21.5 of the DSU, requested an Article 21.5 panel to amend a rule in its working procedures similar to the contested portion of Rule 9 of the Working Procedures. Two of those panels denied the request by the European Communities. (Panel Report, Australia —Measures Affecting Importation of Salmon — Recourse to Article 21.5 of the DSU by Canada, WT/DS18/RW, adopted 20 March 2000, paras. 7.5-7.6; and Panel Report, Australia —Subsidies Provided to Producers and Exporters of Automotive Leather —Recourse to Article 21.5 of the DSU by the United States, WT/DS126/RW and Corr.l, adopted 11 February 2000, paras. 3.9-3.10) According to the United States, a similar decision refusing the request of the European Communities was taken by the panel in a third case, although such decision was not published as the parties ultimately reached a mutually acceptable solution. (Panel Report, United States —Anti- Dumping Duty on Dynamic Random Access Memory Semiconductors (DRAMS) of One Megabit or Above from Korea —Recourse to Article 21.5 of the DSU by Korea, WT/DS99/RW, 7 November 2000; Decision of the panel concerning the EC request for access to the parties’ rebuttal submissions, 27 June 2000, reproduced in part in the United States’ first submission to the Panel, para. 236; Panel Report, p. A-103) One panel agreed to modify its working procedures to provide that the third parties in those proceedings were entitled to receive all written submissions submitted by the parties prior to the single substantive meeting of the panel. (Panel Report, Canada —Measures Affecting the Importation of Milk and the Exportation of Dairy Products —Recourse to Article 21.5 of the DSU by New Zealandandthe United States ;“Canada -Dairy (Article 21.5 —New Zealand and US)“), WT/DS103/RW, WT/DS113/RW, adopted 18 December 2001, as reversed by the Appellate Body Report, WT/DS103/AB/RW, WT/DS113/AB/RW, paras. 2.32-2.35) This is the first occasion on which this issue has been raised on appeal.

204 Article 21.5 of the DSU contemplates that panels will complete their work within 90 days, whereas Articles 12.6 and 12.8 of the DSU contemplate that panels will circulate their reports within six months.

205 Appellate Body Report, Argentina —Measures Affecting Imports of Footwear, Textiles, Apparel and Other Items, WT/DS56/AB/R and Corr.l, adopted 22 April 1998, DSR 1998:111, 1003, para. 79.

206 Ibid.

207 Appellate Body Report, India —Patent Protection for Pharmaceutical and Agricultural Chemical Products, WT/DS50/AB/R, adopted 16 January 1998, DSR 1998:1, 9, para. 92.

208 Appellate Body Report, United States —Anti-Dumping Act of 1916 (” US —1916 Act“), WT/DS136/AB/R, WT/DS162/AB/R, adopted 26 September 2000, para. 145.

209 Appellate Body Report, US —1916 Act, supra, footnote 208, para. 150. See also Appellate Body Report, EC-Hormones, supra, footnote 40, para. 154.

210 We note, in this regard, that paragraph 6 of Appendix 3 to the DSU also links the participatory rights of third parties to this step in the proceeding. It states that third parties “ shall be invited in writing to present their views during a session of the first substantive meeting of the panel.” (emphasis added)

211 We note, in that respect, that the DSU does not place any limits on the number of submissions which panels can request of the parties in advance of the first meeting.

212 Panel Report, para. 6.3, subpara. 5.

213 Ibid., para. 6.3, subpara. 9. (emphasis added)

214 Paragraph 12 of Appendix 3 to the DSU recognizes that the standard timetable for panels may be adjusted to allow for “additional meetings with the parties”, including a possible meeting at the stage of interim review.

215 Panel Report, supra, footnote 203, para. 2.34.

216 Panel Report, paras. 8.108, 8.162-8.163 and 8.171.

217 European Communities'other appellant's submission, para. 31.

218 Ibid., para. 30.

219 United States’ appellee's submission, para. 13.