No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

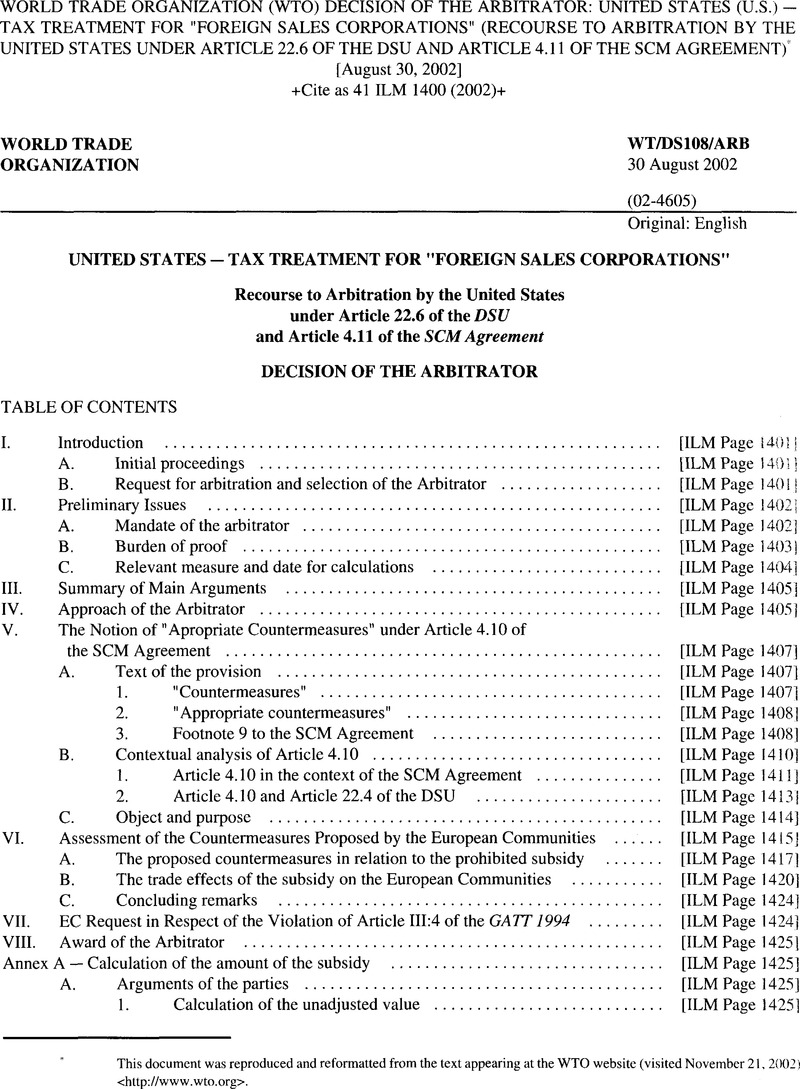

World Trade Organization (WTO) Decision of the Arbitrator: United States (U.S.) - Tax Treatment for “Foreign Sales Corporations” (Recourse to Arbitration by the United States Under Article 22.6 of the DSU and Article 4.11 of the SCM Agreement)*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 18 May 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 2002

Footnotes

This document was reproduced and reformatted from the text appearing at the WTO website (visited November 21, 2002) <http://www.wto.org>.

References

Endnotes

1 Panel Report, United States — Tax Treatment for "Foreign Sales Corporations" ("US — FSC")WT/DS108/R, adopted 20 March 2000 as modified by original Appellate Body Report, WT/DS108/AB/R, DSR 2000:IV, 1677, para. 8.8.

2 See Minutes of the DSB meeting held on 12 October 2000, WT/DSB/M/90, paras. 6-7.

3 WT/DS 108/11,2 October 2000.

4 United States Public Law 106-519, 114 Stat. 2423 (2000), submitted as Exhibit EC-5; Exhibit US-1. in the Article 21.5 Compliance Panel proceedings.

5 Minutes of the DSB meeting held on 17 November 2000, WT/DSB/M/92, para. 143.

6 Circulated as document WT/DS 108/12, 5 October 2000.

7 Ibid, para. 8.

8 Ibid, para. 10.

9 WT/DS 108/12, para. 11.

10 See WT/DS 108/15.

11 See WT/DS 108/17.

12 See WT/DS 108/18.

13 EC response to question 2 of the Arbitrator.

14 On the notion of “difference,” see Report of the Appellate Body on Guatemala —Anti-Dumping Investigation Regarding Portland Cement from Mexico (“Guatemala —Cement I“), WT/DS60/AB/R, adopted 25 November 1998, DSR 1998:IX, paras. 65 and 66.

15 EC first submission, para. 6 and US first submission para. 27.

16 US first submission, para. 27.

17 Report of the Appellate Body, United States —Measure Affecting Imports of Woven Wool Shirts and Blouses from India (“US — Wool Shirts and Blouses“), WT/DS33/AB/R, adopted 23 May 1997, DSR 1997:1, 323, at 337.

18 For previous application of these rules in arbitration proceedings under Article 22.6 of the DSU, see Decision by the Arbitrators, European Communities — Measures Concerning Meat and Meat Products (Hormones) — Original Complaint by Canada — Recourse to Arbitration by the European Communities under Article 22.6 of the DSU (“EC —Hormones (Canada) (Article 22.6 — EC), WT/DS48/ARB, 12 July 1998 DSR 1999:111, 1135, paras. 8 ff. For an application in the context of Article 4.10 of the SCM Agreement, see Decision by the Arbitrators, Brazil —Export Financing Programme for Aircraft —Recourse to Arbitration by Brazil under Article 22.6 of the DSU and Article 4.11 of the SCM Agreement, (Brazil -Aircraft, (Article 22.6 Brazil)“) WT/46/ARB, 28 August 2000, paras. 2.8 ff.

19 Report of the Appellate Body, US — Wool Shirts and Blouses, p. 14.

20 Report of the Appellate Body, Canada — Measures Affecting the Export of Civilian Aircraft (“Canada — Aircraft“), WT/DS70/AB/R, adopted 20 August 1999, DSR 1999:111, 1377, para. 190.

21 WT/DS 108/11.

22 Ibid.

23 We recall that, in EC — Bananas III, the arbitrators considered that the level of proposed suspension of concessions had to be assessed in relation to the measure taken in order to comply with the recommendations and rulings of the DSB, rather than the original measure. See WT/DS27/ARB, para. 4.3: “In the original Bananas III dispute, the findings of nullification and impairment were based on the conclusion that several parts of the EC measures at issue were inconsistent with its WTO obligations. Therefore, any assessment of the level of nullification or impairment presupposes an evaluation of consistency or inconsistency with WTO rules of the implementation measures taken by the European Communities, i.e. the revised banana regime, in relation to the panel and Appellate Body findings concerning the previous regime.“

24 WT/DS108/13.

25 Decision by the Arbitrator, EC —Hormones, WT/DS48/ARB, paras. 38 to 42 and Decision of the Arbitrator, Brazil —Aircraft, WT/DS46/ARB, para. 3.66.

26 We note that the arbitrator in Brazil —Aircraft based its calculations on the number of deliveries and sales that took place between the end of the period of implementation and the latest period for which figures were available (18 November 1999-30 June 2000). However, this solution was based on the particular circumstances of the case, where the amount of subsidy granted was specifically related to the delivery of aircraft after the end of the reasonable period of time.

27 See Annex 1, “shift to the ETI Act.“

28 We recall, in particular, that the ETI act's provisions “grandfathering” the FSC subsidies were part of the subject of examination in the compliance proceedings.

29 EC answers to additional questions from the arbitrator, para. 4 and US answers to additional questions, para. 2.

30 US second submission.

31 US first submission, para. 15.

32 US first submission, paras. 16 to 57.

33 US first submission, para. 62.

34 US Exhibit 17.

35 US second submission, para. 4. In its first submission, the United States had initially estimated the actual value of the subsidy at a lower figure. However, it subsequently re-evaluated that amount to take account of certain EC arguments concerning the relevant elements for the calculation. The amount cited here is the US figure for the amount of the subsidy as adjusted to take account of the coverage of the subsidy and the shift to the ETI Act. A more detailed analysis of the relevant factors and figures can be found in Annex 1.

36 EC second submission para 22.

37 The full text of Article 31 of the Vienna Convention reads as follows:

-

1. A treaty shall be interpreted in good faith in accordance with the ordinary meaning to be given to the terms of the treaty in their context and in the light of its object and purpose.

-

2. The context, for the purpose of the interpretation of a treaty shall comprise, addition to the text, including its preamble and annexes: (a) any agreement relating to the treaty which was made between all the parties in connexion with the conclusion of the treaty; (b) any instrument which was made by one or more parties in connexion with the conclusion of the treaty and accepted by the other parties as an instrument related to the treaty.

-

3. There shall be taken into account together with the context: (a) any subsequent agreement between the parties regarding the interpretation of the treaty or the application of its provisions; (b) any subsequent practice in the application of the treaty which establishes the agreement of the parties regarding its interpretation; (c) any relevant rules of international law applicable in the relations between the parties.

-

4. A special meaning shall be given to a term if it is established that the parties so intended.

38 Our analysis, in this section, of the terms “appropriate countermeasures” as contained in Article 4.10 of the SCM Agreement (as informed by footnote 9), should be understood to apply also the same terms as they are contained in Article 4.11 (as informed by footnote 10).

39 The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (1993).

40 Ibid.

41 Webster's New Encyclopaedic Dictionary (1994).

42 The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (1993).

43 Webster's New Encyclopaedic Dictionary (1994).

44 The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (1993).

45 Webster's New Encyclopaedic Dictionary (1994).

46 Webster's New Encyclopaedic Dictionary (1994).

47 The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (1993). Vol. I, p. 700.

48 Ibid.

49 See, on that issue, the Case Concerning the Air Services Agreement of27 March 1946 (United States of America v. France) (1978) International Law Reports, Vol. 54 (1979), p. 304 (hereafter “Air Services arbitration“): “It has been observed, generally, that judging the proportionality of countermeasures is not an easy task and can at best be accomplished by approximation” (at para. 83, p. 338).

50 On this point, see WT/DS46/ARB, para. 3.51.

51 We would only add on this point that, as regards countering any demonstrated effects, the standard of judgement is still that of appropriateness, in the sense of being not disproportionate, by which we take it to mean a judgement that does not require mathematical exactness of equivalence but that of proportionality in the sense of not being manifestly excessive. We see this as consistent with the view of the arbitrator in Brazil —Aircraft (footnote 55) to the effect that “'appropriate’ should not be given the same meaning as ‘equivalent', but should be understood as giving more discretion in the appraisal of the level of countermeasures against prohibited subsidies.“

52 We note in this regard the view of the commentator, Sir James Crawford, on the relevant Article of the ILC text on State Responsibility, reflected in a resolution adopted on 12 December 2001 by the UN General Assembly (A/RES/56/83), which expresses — but only in positive terms — a requirement of proportionality for countermeasures:

“the positive formulation of the proportionality requirement is adopted in Article 51. A negative formulation might allow too much latitude.” (J. Crawford, The ILC's Articles on State Responsibility, Introduction, Text and Commentaries 2002, CUP, para. 5 on Article 51).

Article 51 of the ILC Articles on State responsibility (entitled “Proportionality“ reads as follows:

“countermeasures must be commensurate with the injury suffered, taking into account the gravity of the internationally wrongful act and the rights in question.” (emphasis added)

We also note in this respect that, while that provision expressly refers — contrary to footnote 9 of the SCM Agreement — to the injury suffered, it also requires the gravity of the wrongful act and the right in question to be taken into account. This has been understood to entail a qualitative element to the assessment, even where commensurateness with the injury suffered is at stake. We note the view of Sir James Crawford on this point in his Commentaries to the ILC Articles:

“Considering the need to ensure that the adoption of countermeasures does not lead to inequitable results, proportionality must be assessed taking into account not only the purely “quantitative” element of the injury suffered, but also “qualitative” factors such as the importance of the interest protected by the rule infringed and the seriousness of the breach. Article 51 relates proportionality primarily to the injury suffered but “taking into account” two further criteria: the gravity of the internationally wrongful act, and the rights in question. The reference to “the rights in question” has a broad meaning, and includes not only the effect of a wrongful act on the injured State but also on the rights of the responsible State. Furthermore, the position of other States which may be affected may also be taken into consideration.” (op. cit., para. 6 of the commentaries on Article 51).

53 See US first submission, paras. 32 ff.

54 See US first submission, para. 44.

55 The United States acknowledges that Article 4.10 does not require the strict equivalence imposed under Article 22.4 of the DSU. Nonetheless, it construes the “appropriateness” of countermeasures under Article 4.10 fundamentally as a “trade effects” test of a nature comparable to that foreseen under Article 22.4. See US answers to questions by the Arbitrator, paras. 4 and 5.

56 We are aware of the provisions of Article 31 of the SCM Agreement and that Members took no action to extend the application of the provisions of Articles 8 and 9 of the Agreement concerning non-actionable subsidies beyond the period of five years from the date of entry into force of the WTO Agreement. However, these provisions can nevertheless be helpful, in our view, in understanding the overall architecture of the Agreement with respect to the different types of subsidies it sought and seeks to address.

57 See for example the reports of the Appellate Body in India — Quantitative Restrictions, WT/DS90/AB/R, DSR 1999:IV. 1763, para 94; EC - Hormones, WT/DS26/AB/R, and WT/DS48/AB/R, DSR 1998:1, 135, para. 181; India - Patents (US).WT/DS50/AB/R, DSR, 1998:1, 9, para. 45.

58 See for example the reports of the Appellate Body on US — Gasoline, WT/DS2/AB/R, DSR 1996:1, 3, at 21 and Korea — Dairy, WT/DS98/AB/R, DSR 2000:1, 3, para. 81.

59 See paras. 4.24-4.26 above.

60 With respect to the differences in the elements defining the applicable obligations, we recall that Article 3.1 (a) of the SCM Agreement — containing the defining elements of prohibited export subsidies — provides: “3.1 Except as provided in the Agreement on Agriculture, the following subsidies, within the meaning of Article 1, shall be prohibited: (a) subsidies contingent, in law or in fact,4 whether solely or as one of several other conditions, upon export performance, including those illustrated in Annex I;“5 (original footnote)

4.This standard is met when the facts demonstrate that the granting of a subsidy, without having been made legally contingent upon export performance, is in fact tied to actual or anticipated exportation or export earnings. The mere fact that a subsidy is granted to enterprises which export shall not for that reason alone be considered to be an export subsidy within the meaning of this provision.

61 Thus, the concept of “adverse effect” is indeed to be found in the SCM Agreement, but only in relation to provisions that contrast with the prohibition on export subsidies in Article 4. Article 7 makes it clear that when a member considers that the granting or maintaining of a subsidy results in, inter alia, nullification or impairment, the provisions on remedies pursuant to that Article will apply. It should be emphasized that a positive finding of nullification and impairment is, by definition, also a finding of “adverse effects” (this ultimately deriving from the use of i.e. in Article 5 which makes it plain that nullification and impairment is one category of the overarching concept of “adverse effects” under the SCM Agreement.). It is also to be noted that where a positive finding is made, the party concerned may either “remove the adverse effects of the subsidy” (Article 7.9) or “withdraw the subsidy” (ibid.). In a situation where there is non-compliance by the party against whom a finding has been made, the complaining Member is entitled “to take countermeasures, commensurate with the degree and nature of the adverse effects determined to exist.“

62 SCM Agreement, Article 7.2.

63 SCM Agreement, Article 4, including Article 4.12.

64 SCM Agreement, Article 4.7.

65 One might note, in passing, that there is no provision for compensation in a nullification and impairment case under these provisions of the SCM Agreement as there is provided for under Article XXIII GATT 1994 and the Article 22 of the DSU, although that is not important for present purposes.

66 Of course, as a logical matter, removal of the measure would certainly encompass a suppression of effects. One might underline here that is a matter of removal of all effects: the practical effect of the remedy provided for under Article 4 is clearly to eliminate a measure in its entirety-including its effects. That is clearly distinct from the practical effect of the Article 5 and 7 disciplines under which it is envisaged that a remedy can be applied which would ensure elimination of the effect on a complaining party but where the possibility of effects on other parties remains.

67 See, e.g., the Naulilaa arbitral award (1928), UN Reports of International Arbitral Awards, Vol. II, p. 1028 and the Air Services arbitration, op. cit.

68 Resolution of the General Assembly of the UN, A/RES/56/83, Responsibility of States for internationally wrongful Acts, adopted on 12 December 2001. We note that the ILC's work is based on relevant State practice as well as on judicial decisions and doctrinal writings, which constitute recognized sources of international law under Article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice.

69 See J. Crawford, op. cit., p. 286. This author notes in particular that “countermeasures are taken as a form of inducement, not punishment” (para. 7 of the Commentaries on Article 49).

70 Decision by the Arbitrators, European Communities —Regime for the Importation, Sale and Distribution of Bananas —Recourse to Arbitration by the European Communities under Article 22.6 of the DSU (“EC — Bananas HI (US) (Article 22.6 — EC)“), WT/DS27/ARB, 9 April 1999, DSR 1999:11, 725, para. 6.3.

71 Supra, para. 5.22.

72 Of course, the balance of rights and obligations between Members will only ultimately be properly redressed through full compliance with the DSB's recommendations, i.e., in this case, withdrawal of the unlawful subsidy. Countermeasures merely offer a temporary and imperfect redress to the persisting violation, which in no way reduces the need to comply or substitutes for such compliance.

73 For a detailed analysis of the value of the subsidy, see Annex A below.

74 One of the arbitrators wishes to stress that this and the following paragraph should not be read to mean that, without regard to the particular circumstances of individual cases, the total amount of the subsidy would be a universally and generally applicable standard at all times.

75 See supra para. 5.18.

76 For a detailed analysis of calculations of the amount of the subsidy, see Annex A below.

77 For a detailed analysis of the value of the subsidy, see Annex A below.

78 See WT/DS46/ARB, para. 3.60.

79 This is not necessarily the case, e.g., for the effects of the measure, it being understood, of course, that as regards responsibility, this extends also to the consequences as well as the act.

80 The European Communities has referred, in the course of the proceedings, to the notion of benefits to the United States of the scheme in the context of proposing alternative methodological approaches to calculate an amount of “appropriate countermeasures” and suggests that “since the benefits the US derives from the FSC/ETI scheme are higher than the value of the subsidy, the imposition of countermeasures equivalent to the value of the subsidy can be seen to be a modest and conservative estimate of what is required to induce compliance” (First submission, para. 69). It has also argued that it had proposed “countermeasures based on the — and proportionate to — the benefit provided by the FSC-ETI scheme to United States exporters” (Second submission para. 55). However, the European Communities has not sought to directly quantify these benefits to demonstrate an exact correspondence between these benefits and the amount it is suggesting in this instance. Rather, it argues that these benefits would be higher than the amount of the subsidy.

81 We would only observe that our judgement is, in any case, simply that the countermeasures sought by the European Communities are not disproportionate, based on our reasoning and the facts of this case. In determining that, we have not necessarily defined this quantum of countermeasures as being the definitive limit. We have not made — and do not make — any judgement on that matter. The only question before us is whether the amount sought by the European Communities is not disproportionate.

82 One of the arbitrators wishes to stress that under different circumstances in a particular case, this consideration alone may not automatically lead to the conclusion that the countermeasures are “appropriate” within the meaning of Article 4.10 of the SCM Agreement.

83 EC response to question 42 from the Arbitrator, para. 116.

84 See para. 5.41 above. For instance, it is conceivable that some adverse effects on a Member could be manifestly greater than the amount of the subsidy that is expended. In such cases, the Agreement can hardly be construed to preclude a Member from taking countermeasures to deal with that situation precisely on the basis of adverse trade effects or that Member — especially when that would otherwise mean that they had recourse thereby only to countermeasures that would be less effective than those available to a Member under Article 5 of the SCM Agreement (or for that matter under the countervailing provisions of the Agreement, where the other conditions for application would also be present). That is not, of course, the situation we are dealing with here. The European Communities is not seeking entitlement to countermeasures greater than the face value of the subsidy.

85 Amount of the subsidy for the year 2000 as calculated by the United States, including relevant adjustments.

86 See US First submission, para. 69.

87 See US Second Submission, para. 4.

88 See the Decision of the Arbitrator, Brazil —Aircraft (Article 22.6 —Brazil) WT/DS46/ARB, para. 3.54 (“given that export subsidies usually operate with a multiplying effect (a given amount allows a company to make a number of sales, thus gaining a foothold in a given market with the possibility to expand and gain market shares), we are of the view that a calculation based on the level of nullification or impairment would, as suggested by the calculation of Canada based on the harm caused to its industry, produce higher figures than one based exclusively on the amount of the subsidy“).

89 Assuming full pass through of the subsidy, a value of -1.65 for the price elasticity of the aggregate US export demand curve will result in the value of the trade effect equalling the value of the subsidy (see exhibit US-17).

90 The quantitative estimate of the impact of an export subsidy on trade depends upon the relationship between the mode of delivery of the subsidy and various economic parameters. In this case the subsidy is allocated on the basis of export income. Eligible export income is used to reduce the overall tax burden of a firm. The overall impact depends upon four factors: the value of the subsidy; the reduction in the price of the good benefiting from the subsidy; the export response of producers benefiting from the subsidy; and the price elasticity of demand for US exports.

91 EC First Submission, paragraph 62. For example, using the US Treasury model as proposed by the European Communities and the estimated subsidy values of both the European Communities and the United States for industrial products as set out in Annex A, the range of the estimated trade effects can be estimated between $3,253 million and $4,294 million.

92 The United States proposed the Armington model, which assigns elasticities to products based on their country of origin. Therefore. the model, according to the United States, has the advantage of isolating the EC specific trade impact of the subsidy (US Second submission, para 122).

93 The United States took the position that “imputed” elasticity estimates from estimated substitution elasticities are more robust than the estimates provided by the European Communities. The calculations provided by the United States were justified on the grounds that they were more recent and could be calculated at a disaggregate level.

94 While we acknowledge the general contribution that the Armington approach to modelling differentiated products models of trade can make, the United States did not, in the case before us, satisfactorily explain why we would be obliged to find the particular approach suggested by it to be more reasonable than that generated by the proposed EC approach. On the contrary, the United States’ approach had demonstrable flaws as it sought to apply it in this case. We note that, in this case, the estimation of the trade impact of the subsidy generated by the United States using the Armington model does not in fact employ EC-specific cross price elasticities nor does it use specific elasticities of US export demand (US Second submission, footnote 97). Furthermore, in response to a question from the Arbitrator relating to the use of the alternative methodology, the United States underlined the lack of reliable basis to use this approach. Its response was that “Although the United States could not find the information necessary to distinguish between the EC and the rest of the world, the Armington model runs, nevertheless, at least furnish the Arbitrator with an independent assessment of the trade impact of the US subsidy on the EC based on a different set of parameter estimates” (emphasis added) (Para. 30, US Response to Additional Questions by the Arbitrator). The United States also stated that it lacks information, which if available would have allowed them to calculate the trade effects with more precision. “With this additional information, the Armington model may have possibly provided better guidance than the Treasury model, because it would have incorporated more information (i.e. the degree of substitutability between US exports and EC goods) and would have avoided the need to determine how to calculate the EC share” (US Answers to Additional Questions from the Arbitrator, paragraph 30) (emphasis added). Thus, at most, the United States hypothesizes that there could be a more reliable and robust approach. It however has been itself unable to give us a reliable alternative basis to make a judgement that would definitively prevail over any based on the Treasury model.

95 The United States submitted that the range of estimates of the point price elasticity of the aggregate US export demand is between -1.13 and -2.53, whereas the simple average of the estimates of the price elasticities used in the US Treasury study is -3.0. The difference between these estimates, the United states argues, is one reason why the US Treasury model would lead to overestimates of the actual trade impact. The United States, however, did not submit evidence to support the use of these alternative aggregate stimates. More to the point, it did not deal with the fact that four sectors alone in the US Treasury study account for 66 per cent of the total FSC exempt income and pursuant to the US Treasury study, these have estimates at the sectoral level of -1.7, -3.8, -4.1. -3.8 respectively. Given the weight of these sectors in the overall trade effect of the subsidy, the value of the price elasticity of these sectors should be the focus of analysis. This is consistent with the view that simple aggregate elasticities would be more inherently likely to underestimate elasticities for the purposes of an analysis of the FSC/ETI scheme.

96 The United States took the position that ‘imputed’ elasticity estimates from estimated substitution elasticities are more robust than the estimates provided by the European Communities. The calculations provided by the United States were justified on the grounds that they were more recent and could be calculated at a disaggregate level. The process by which the elasticities are imputed, however, was never clearly specified by the United States. The original estimates from which the imputed estimates are done were sourced from two academic studies (Gallaway et al. (2001); Shiells and Reinert (1993)). Both studies relate to the United States. We note that these estimates are derived from demand functions for US consumers. Therefore, these estimates relate to the degree of substitution between imported products into the United States and domestically produced products for US consumers. The United States did not establish why measures of elasticities of imports into the United States could be used as estimates of elasticities of exports. In our view, the United States failed to effectively respond to three reasons identified by the EC as a cause for concern about the procedure used by the United States:

“The Armington elasticity estimates used by the United States are for substitution between imports into the United States and domestically produced US products. These are not the same as substitution elasticities between US exports and domestically produced products in foreign countries. First, the foreign countries will have different policies towards imports. Second, foreign consumers will have tastes and preferences that are different from US consumers. Third, it is likely that the set of trade goods in an industry is not the same as the set of domestically produced goods offered for local sale. Therefore, the set of US exported goods is not the same as the set of domestically produced goods offered for sale in the United States, and the set of goods imported into the United states is not the same as the set of foreign produced goods offered for sale in foreign countries.” ( EC comments on US Responses to Additional Questions from the Arbitrator, para 5).

97 The issue of pass through relates to the degree to which a company uses a subsidy it receives to lower the price of the product that it exports. At one extreme the company may choose to apply the full amount of the subsidy to the price of its products, thereby lowering its price. At the other, it may choose not to lower the price of the product. The concept of pass through is further explained in paragraph 89 of US Answers to Questions from the Arbitrator:

“An exporter presented with the FSC/ETI tax savings can do one of two things. One the one hand, it can lower the price of its exports by the amount of the tax savings. If it does this, its net profit per transaction will remain the same, although its overall profits may increase because — other factors being held constant — the volume of its exports will increase. This is the “full pass through” scenario.

Alternatively, the exporter can leave the price of its exports unchanged. If it does this, the volume of its exports will remain unchanged — other factors being held constant — but its net profit per transaction will increase by the amount of the tax savings. This is the “no pass-through scenario.“

98 The United States asserts that “pass-through is so critical that if it were determined that firms completely absorbed the tax subsidy rather than reflecting it in export prices, the subsidy would have no effect on US exports and the quantification of the trade impact would be zero.” (US Oral Statement, para. 56).

99 US Answers to Questions from the Arbitrator, para 94.

100 US Answers to Questions from the Arbitrator, paras 95-97.

101 US Answers to Questions from the Arbitrator, para 98-99.

102 EC Answers to Questions from the Arbitrator, para 134.

103 The market access landscape for industrial products as a result of the Uruguay Round was a reduction in average tariffs of 40 per cent from 6.3 per cent to 3.8 per cent. Furthermore, the proportion of products entering duty-free in the developed country markets would increase from 20 to 44 per cent, while the proportion of products facing tariffs above 15 per cent declined from 7 to 5 per cent GATT Secretariat (1994), The Results of the Uruguay Round of Multilateral Trade Negotiations, Geneva, GATT). In addition, the United States did not successfully rebut arguments presented by the European Communities as to the increasing global competition in markets for industrial goods. In particular, the European Communities cited relevant economic literature suggesting rising global competition to US firms (see EC Answer to Question 47 by the Arbitrator).

104 An upper limit would be 100 per cent, whereas a lower limit could be the estimate for the similar programme in the 1970s of 75 per cent (see EC Answers to Questions from the Arbitrator, para. 134).

105 See paragraph 5.62 above.

106 As a practical application, one could relate this to pass through. Even if one took the view that there was no decisive evidence for 100 per cent pass through, in a situation where plausibility was at stake, say, as between 75, 90 or 100 per cent, it would need to be borne in mind that the prohibition of export subsidies is not inherently conditioned on whether or not the export subsidy is entirely passed through into prices. A dollar of export subsidy is a dollar of export subsidy. That being so, in circumstances where there is no decisive element to opt for one particular alternative, the direction in footnote 9 comes into play, to the effect that there is no presumption that a lower option should prevail.

107 We recall that the United States itself considered that they did not provide a reliable tool, in this case, to estimate these effects, in light of the number of uncertain variables that would need to be accounted for.

108 We refer to paragraph 6.29 above and the European Communities’ statement in this respect.

109 EC response to Question 2 of the Arbitrator.

110 We note in this respect that the European Communities argued in the course of the proceedings that more recent actual data should be available through a report to be presented to Congress for the period 1997-2000. In response to a question by the Arbitrator, the United States indicated that the US Department of the Treasury has been collecting and processing data on the operation of the FSC programme every four years since 1992, and that the most recent year for which data have been collected and analyzed in 1996. While data has been collected for the year 2000, the “finished data” for tax year 2000 should be available by the end of 2002. Publication of the analyzed data is not expected before 2004. The United states also indicates that the production of tax returns would not be permissible under US law, and that the use of selected data would produce an unreliable and potentially very misleading picture of the programme's operation in the year 2000 ﹛see US answers to Questions, paras. 75 to 83).

111 Exhibits EC 11 and US 15.

112 These are summarized in exhibits EC 11 and US 15.

113 Para. 34.

114 EC first submission para 41.

115 EC-3.

116 Para. 7.

117 Page 28.

118 Page 29.

119 US first submission para 74 .

120 US Second submission para. 84.

121 US Second Submission paragraphs 77-78.

122 US Second Submission para. 84.

123 US Second Submission para. 86.

124 EC Oral Statement para. 47.

125 EC Oral Statement, para. 50.

126 EC Oral Statement, para. 50.

127 US Answers to questions from the Arbitrator, para. 122.

128 US Answers to questions from the Arbitrator, para. 122.

129 Question 10 of Additional Questions from the Arbitrator and the response of the United States to that question.

130 EC Second submission paras 40-45.

131 EC Oral Statement, para 52 and Exhibit EC-11.

132 EC Comments on US Responses to Additional Questions from the Arbitrator, para 16.

133 EC Comments on US Answers to Additional Questions from the Arbitrator, para 17.

134 EC Comments on US responses to Additional Questions from the Arbitrator, para 19.

135 The data is produced in exhibit EC 17 and the study was submitted as Exhibit EC 15.

136 EC Response to questions from Arbitrator, para. 52.

137 EC first submission, para. 93.

138 US Second Submission, para. 23.

139 This amount was based on 2000 SOI data: i.e. the proportion.

140 EC second submission, para. 86.

141 See Hormones and Aircraft arbitrations, op. cit.

142 See above paras. 2.14 and 2.15.

143 Exhibit EC 11 and paragaph 73 of US Second submission.

144 The formula is V=A(1 + g)1. Where V is the final value, A is the initial value, t is the number of time periods, and g is the annual average growth rate.

145 US Answers to Additional questions, response to question 10.

146 US Second Submission para 23.

147 We recall that under the ETI Act, certain income of a United States taxpayer may be excluded from taxation. Such income — “extraterritorial income” that is “qualifying foreign trade income” — may be earned with respect to goods only in transactions involving qualifying foreign trade property. Outside the goods area, such income may be earned in relation to services which are related and subsidiary to (i) any sale, exchange, or other disposition of qualifying foreign trade property, or (ii) any lease or rental of certain qualifying foreign trade property; for engineering or architectural services for construction projects located (or proposed for location) outside the United States; or for the performance of managerial services for a person other than a related person in furtherance of the production of certain foreign trading gross receipts. ETI Act, section 3; section 942 IRC, as described in Compliance Panel Report, para. 2.3 and note 23.

148 See US first submission, para. 73; US Second Submission, para. 88; EC first submission, para. 93.

149 First Submission para. 88.

150 We recall that the 21.5 panel in this case made a separate ruling that the FSC/ETI scheme was in violation of the Agreement on Agriculture, in addition to the SCM Agreement. The Appellate Body upheld this finding (Article 21.5 Appellate Body Report, para. 256(d)). We also note, in respect of the deduction for agricultural products discussed here, that if a separate assessment were made to evaluate the level of nullification or impairment resulting from the violation of the Agreement on Agriculture, this could provide a separate basis for suspension of concessions which would in any event not lower the entitlement to countermeasures under the SCM Agreement.

151 See Agreement on Agriculture, Annex I.

152 From WTO, Unfinished Business.

153 Two of the submissions received are not reproduced, at the request of the submitting parties concerned.