No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

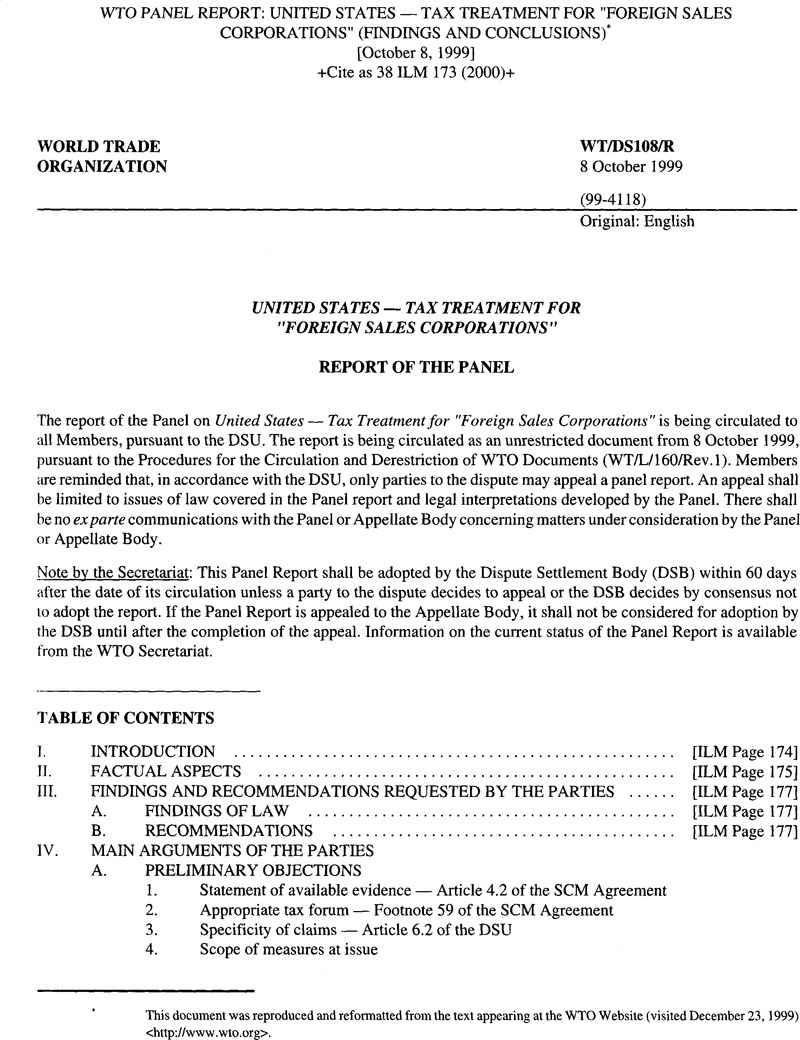

WTO Panel Report: United States — Tax Treatment for “Foreign Sales Corporations” (Findings and Conclusions)

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 2000

Footnotes

This document was reproduced and reformatted from the text appearing at the WTO Website (visited December 23,1999) <http://www.wto.org>.

References

1 See the European Communities’ request for consultations, WT/DS108/1 (28 November 1997).

2 WT/DS108/l/Add.l (12 March 1998).

3 WT/DS108/2 (9 July 1998).

4 WT/DS108/3 (11 November 1998).

5 Certain exceptions to this definition of export property may be found in Section 927(a)(2) of the IRC. They are: (a) property leased or rented by a FSC for use by any member of a controlled group of corporations of which such FSC is a member; (b) patents, inventions, models, designs, formulas, or processes whether or not patented, copyrights (other than films, tapes, records, or similar reproductions, and other than computer software (whether or not patented), for commercial or home use), good will, trademarks, trade brands, franchises, or other like property; (c) oil or gas (or any primary product thereof); (d) products the export of which is prohibited or curtailed to effectuate the policy set forth in paragraph (2)(C) of section 3 of the Export Administration Act of 1979 (relating to the protection of the domestic economy); and (e) any unprocessed timber which is a softwood. For purposes of subparagraph (e), the term “unprocessed timber” means any log, cant, or similar form of timber.

6 Section 922(a) of the IRC.

7 Section 924(b) of the IRC.

8 Such income is generally exempt from tax under section 882 of the Internal Revenue Code, if it is earned by a corporation resident outside the United States.

9 See Section 923(a) of the IRC.

10 Section 926(a) and 245(c) IRC.

11 See Section 923(a)(4) of the IRC.

12 See Section 245(c)(2)(B) of the IRC.

13 Exhibit EC-1.

14 See Sections 925(a) (1) and (2) of the IRC.

15 See Sections 923(a)(3) and 291(a)(4) of the IRC.

16 See Section 925(d) of the IRC.

17 See Section 925(c) of the IRC.

18 Section 924(d) and (e) of the IRC.

588 WT/DS108/1, 28 November 1997.

589 Concise Oxford Dictionary, Ninth edition, 1995.

590 The materials in questions were comprised of testimony before the US Congress, reports and other descriptive materials relating to the FSC prepared by US government officials, articles in tax, legal and business publications about the FSC, copies of the requests for consultations and establishment of a panel in this dispute, and excerpts from OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations. All of these materials are explanatory of the FSC except for the OECD Guidelines, which were submitted in support of the European Communities’ view of the meaning of the concept of the “arm's length“ principle referred to in footnote 59 to the SCM Agreement.

591 Of course, a Member may also request establishment of a panel under Article 4.3 of the DSU if a Member does not respond within ten days after the date of the receipt of the request, or does not enter into consultations within a period of no more than 30 days, or a period otherwise mutually agreed.

592 See Korea — Taxes on Alcoholic Beverages, WT/DS75/R-WT/DS84/R, Report of the Panel adopted on 17 February 1999, paragraph 10.19 (stating, in the context of an argument relating to the adequacy of consultations, that” [t]he only requirement under the DSU is that consultations were in fact held, or were at least requested, and that a period of sixty days has elapsed from the time consultations were requested to the time a request for a panel was made.“)

593 Guatemala—Anti-Dumping Investigation Regarding Portland Cement from Mexico, WT/DS60/AB/R, Report of the Appellate Body adopted on 25 November 1998.

594 European Communities — Regime for the Importation, Sale and Distribution of Bananas, WT/DS27/AB/R, Report of the Appellate Body adopted on 25 September 1997, paragraph 142.

595 See paragraphs 7.134 - 7.143, infra.

596 European Communities — Customs Classification of Certain Computer Equipment, WT/DS62/AB/R-WT/DS67/AB/R- WT/DS68/AB/R, Report of the Appellate Body adopted on 22 June 1998, paragraph 67.

597 Footnote 65,supra.

598 European Communities — Regime for the Importation, Sale and Distribution of Bananas, WT/DS27/AB/R, Report of the Appellate Body adopted on 25 September 1997, paragraph 142.

599 European Communities — Customs Classification of Certain Computer Equipment, WT/DS62/AB/R-WT/DS67/AB/R- WT/DS68/AB/R, Report of the Appellate Body adopted on 22 June 1998, paragraph 67.

600 WT/DS108/2, 9 July 1998.

601 WT/DS108/2 dated 9 July 1998.

602 We have examined Section 245(c) of the US Internal Revenue Code in respect of the dividends-received deduction for shareholders of a FSC and Section 951 (e) of the US Internal Revenue Code in respect of the exemption of foreign trade income of a FSC from the anti-deferral rules. See paragraphs 7.96-7.97, infra. Sections 245(c) and 951(e) were however identified in the European Communities’ first written submission (paragraph 65). Accordingly, the terms of the United States’ preliminary objection do not extend to these provisions.

603 Tax Legislation, BISD 28S/114, 7-8 December 1981.

604 European Communities — Regime for the Importation, Sale and Distribution of Bananas, WTVDS27/AB/R, Report of the Appellate Body adopted on 25 September 1997, paragraph 204.

605 We do not mean to suggest that it would never be appropriate to begin the analysis of an export subsidy issue by reference to the Illustrative List — particularly in a case where the claimant relied primarily upon that List — but merely that we have chosen to begin with Articles land 3 in this case.

606 Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (Third Edition).

607 Paragraph 4.526, supra.

608 Indonesia — Certain Measures Affecting the Automobile Industry, WT/DS54/R-WT/DS55/R-WT/ DS59/R-WT/DS64/R, paragraph 14.155, Report of the Panel adopted on 23 July 1998.v

609 Paragraph 4.591, supra.

610 The United States disputes that the reference point for determining whether revenue foregone is “otherwise due” must as a general matter relate to the generally applicable tax regime of the Member in question, and describes at length the complexity of determining in particular circumstances which rules are the “general” rules and which are the “exceptions”. In the view of the United States, this approach confuses the issue of whether revenue foregone is “otherwise due” with the issue of specificity under Article 2 of the SCM Agreement. The United States has not, however, advocated application of a “but for” approach, nor has it been able to identify any generally relevant alternative to a Member's own tax regime for determining when foregone revenue is “otherwise due”. When asked by the Panel what criteria it considered should be applied when examining whether revenue foregone was “otherwise due”, the United States responded that “one obvious criterion is whether there has ever been a decision or ruling under the same or a related agreement”. Other criteria identified were “the desirability of avoiding results that exalt form over substance” and “the need to have clear rules”. Paragraphs 4.1103-4.1114, supra.

611 Code of Federal Regulations, Section 351.509.

612 63 Federal Register 65376 (25 November 1998).

613 The United States further argues that the 1981 understanding is relevant to interpreting Article 3.1 (a), item (e) of the Illustrative List of Export Subsidies and footnote 59 to that item. Our consideration of the legal status of the 1981 understanding to interpretation of the SCM Agreement is equally applicable in these various contexts.

614 Paragraph 4.847, supra.

615 Japan — Taxes on Alcoholic Beverages, WT/DS8/AB/R-WT/DS10/AB/R-WT/DS11/AB/R, Report of the Appellate Body adopted on 1 November 1996.

616 United States Tax Legislation (DISC), adopted 7-8 December 1981, BISD 23S/98, paragraph 74; Income Tax Practices Maintained by France, adopted 7-8 December 1981, BISD 23S/114, paragraph 53; Income Tax Practices Maintained by Belgium, adopted 7-8 December 1981, BISD 23S/127, paragraph 40; Income Tax Practices Maintained by the Netherlands, adopted 7-8 December 1981, BISD 23S/137, paragraph 40.

617 Tax Legislation, BISD 28S/114, 7-8 December 1981.

618 Ibid.

619 As noted above, the European Communities relies upon the Appellate Body Report in Japan — Alcoholic Beverages for the proposition that the 1981 understanding is not an “other decision” for the purposes of paragraph l(b)(iv) of the language of Annex 1A incorporating the GATT 1994 into the WTO Agreement. In that case, the Appellate Body found that adopted panel reports do not “in themselves” constitute “other decisions of the Contracting parties to the GATT 1947” within the meaning of that provision. We do not consider that Japan — Alcoholic Beverages addresses the precise situation presented in this case. In that dispute, the issue was the status of adopted panel reports themselves. The 1981 understanding, however, was not limited to the adoption of certain panel reports. Rather, the text of the understanding, when read against the background of the Tax Legislation cases, indicates disagreement with certain aspects of those reports. Further, the reports were adopted “on the understanding that with respect to these cases, and in general, economic processes … located outside the territorial limits of the exporting country need not be subject to taxation by the exporting country … .” (emphasis added). Because the 1981 understanding is not simply a decision to adopt certain panel reports, Japan — Alcoholic Beverages does not in itself offer a clear answer to the issue now before us.

620 The parties have argued extensively about whether the 1981 understanding was adopted pursuant to Article XXIIL2 or Article XXV of GATT 1947. In our view, this is not the precise question that should be posed. Article XXV was an umbrella provision regarding decision-making by the Contracting Parties. That Article XXV joint action involved “decision-making” is confirmed by Article XXV:4 of GATT 1947, which provided that, “[e]xcept as otherwise provided for in this Agreement, decisions of the Contracting Parties shall be taken by a majority of the votes cast”. One form of joint action by the Contractingparties involved making appropriate recommendations or giving rulings under Article XXIII, and the 1981 understanding involves, at least in part, joint action under that provision. There are however numerous other provisions “which involve joint action” in GATT 1947 (See John H. Jackson, World Trade and the Law of GATT (Bobs-Merrill, 1969), section 5.4) and Article XXV further provided for joint action “with a view to facilitating the operation and furthering the objectives of GATT 1947”. Thus, even if one takes the view that the 1981 understanding goes beyond making a recommendation or ruling under Article XXIIL2, such action would still have been authorized under Article XXV: 1, which allowed the CONTRACTING PARTIES broad power for decision- making in order to facilitate the operation and furthering of the objectives of GATT 1947. This does not of course mean that the 1981 understanding necessarily represents a decision within the meaning of paragraph l(b)(iv) of the language of Annex 1A incorporating the GATT 1994 into the WTO Agreement to adopt an “interpretation” of GATT 1947. One can imagine numerous forms of joint action under Article XXV: 1, other than interpretations, to facilitate the operation and further the objectives of GATT 1947.

621 Oxford Shorter English Dictionary (Third edition).

622 Japan — Alcoholic Beverages, p. 13 (“We do not believe that the CONTRACTING PARTIES, in deciding to adopt a panel report, intended that their decision would constitute a definitive interpretation of the relevant provisions of GATT 1947.“)(emphasis added).

623 Contracting parties, Thirty-Eighth Session, Summary Record of the First Meeting, SR.38.1, 15 December 1982.

624 Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (Third edition).

625 Black's Law Dictionary (Revised fourth edition).

626 In fact, the term “legal instrument” is used in the immediately preceding paragraph (a) in the context of the rectification, amendment or modification of the text of GATT 1947. This would appear to represent further confirmation of our understanding of the term “legal instrument”.

627 MTN/FA (15 December 1993).

628 It may be noted that, unlike the WTO Agreement, GATT 1947 nowhere specifically provided the Contracting parties with authority to make “interpretations” of GATT 1947 and, although such authority seems to have been widely recognized by the contracting parties, the existence of that power as a legal matter was not entirely clear. See John. H. Jackson, World Trade and the Law of GATT (Bobs-Merrill, 1969), section 5.5 (“In summary, although a careful legal analysis, having particular reference to the preparatory work, could lead one to conclude that the Contracting parties of GATT do not have the legal power to make a binding interpretation of the General Agreement, nevertheless, in practice, the CONTRACTING PARTIES do make interpretations and there seems to be remarkably little objection to those interpretations”.).

629 Council of Representatives, Report on Work Since the Thirty-Seventh Session, L/5414, 12 November 1982.

630 Contracting parties, Thirty-Eighth Session, Summary Record of the First Meeting, SR.38.1, 15 December 1982.

631 As the Appellate Body explained in Japan —Alcoholic Beverages, WT/DS8/AB/R-WT/ DS10/AB/R-WT/DS11/AB/R, Report of the Appellate Body adopted on 1 November 1996, p. 13, under GATT 1947, “the conclusions and recommendations in an adopted panel report bound the parties to the dispute in a particular case, but subsequent panels did not feel legally bound by the details and reasoning of a previous panel report.“[footnotes omitted]

632 Tax Legislation, L/5271, 7-8 December 1981.

633 Footnote 341, supra.

634 Item 4 of the Agenda, C/W/376/Rev.l, 8 December 1981.

635 BISD28S/114.

636 C/M/154, 28 January 1982, p. 6.

637 Ibid., pp. 7-8.

638 Ibid., p. 8.

639 Ibid., p. 8.

640 Paragraph 4.1168, supra.

641 Paragraph 4.380, supra.

642 Paragraphs 7.55-7.56, supra.

643 A number of panels have explicitly or implicitly found that adopted GATT 1947 panel reports fall within the scope of Article XVI: 1 of the WTO Agreement. See, e.g., India — Patent Protection for Pharmaceutical and Agricultural Chemical Products, Report of the Panel adopted, as modified by the Report of the Appellate Body, on 16 January 1998, WT/DS50/R, paragraph 7.19; European Communities — Regime for the Importation, Sale and Distribution of Bananas, Report of the Panel adopted, as modified by the Report of the Appellate Body, on 25 September 1997, WT/DS27/R/US A, paragraph 7.40.

644 Regarding the legal status of adopted panel reports, the Appellate Body in Japan —Alcoholic Beverages (p. 14) explained that: “[a]dopted panel reports are an important part of the GATT acquis. They are often considered by subsequent panels. They create legitimate expectations among WTO Members, and, therefore, should be taken into account where they are relevant to any dispute. However, they are not binding, except with respect to resolving the particular dispute between the parties to that dispute.“

645 Japan—Alcoholic Beverages, p. 14.

646 To take an extreme example, it is highly unlikely that the 1981 understanding would provide relevant guidance with respect to the interpretation of the Agreement on Sanitary and Phytosanitary Measures.

647 Paragraph 4.679, supra.

648 See, e.g., C. Pouncey and K. J. Kuilwijk, WTO Disciplines on Subsidies: An Overview of Residual Problems — Part I, in International Trade Law and Regulation, Vol. 4, Issue 5 (October 1998), p. 173.

649 We recognize that, although not part of the text of Article XVT.4 of GATT 1947, item (c) of the “1960 list” found in the Report of the Working Party relating to the Provisions of Article XVL4 (BISD 9S/185) is similar, although by no means identical, to item (e) of the Illustrative List annexed to the SCM Agreement. We note, however, that item (e) of the Illustrative List is identical — except in regard to certain aspects of footnote 59 — to its counterpart in the Tokyo Round Subsidies Code, and that, as discussed below, the Chairman's statement accompanying the 1981 understanding explicitly precluded the use of the 1981 understanding to interpret the Tokyo Round Subsidies Code.

650 Brazil — Measures Affecting Desiccated Coconut, WT/DS22/AB/R, Report of the Appellate Body adopted on 20 March 1997,p. 16.

651 Paragraph 4.679, supra.

652 Brazil — Measures Affecting Desiccated Coconut, WT/DS22/AB/R, Report of the Appellate Body adopted on 20 March 1997, p. 17.

653 Agreement on Interpretation and Application of Articles VI, XVI and XXIII of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade.

654 Tax Legislation, 28S/114,7-8 December 1981. The United States has argued that, “[b]ecause the Subsidies Code was an agreement that interpreted, inter alia, Article XVI, the [1981 understanding] would have been equally applicable to the provisions of the Subsidies Code …. Thus, going into the Uruguay Round, the FSC was protected by the [1981 understanding] under both Article XVI and the Subsidies Code”. Second Submission of the United States to the Panel, footnote 47. Clearly, this view cannot be reconciled with Chairman's statement that the 1981 understanding “does not affect and is not affected by” the Tokyo Round Subsidies Code.

655 We note that Article XVI: 1 of the WTO Agreement states that the WTO shall be guided by the decisions, procedures and customary practices followed by the Contracting Parties to GATT 1947 “except as otherwise provided under [the WTO Agreement] or the Multilateral Trade Agreements”. In light of our view regarding the lack of relevance of the 1981 understanding to this dispute, we need not and do not address whether the SCM Agreement “provides otherwise” than the 1981 understanding in the sense of Article XVI: 1 of the WTO Agreement.

656 Paragraph 4.523, supra.

657 The United States asserts that this legal principle is relevant both to establishing whether there is a subsidy within the meaning of Article 1 and whether there is an export subsidy within the meaning of Article 3. We address the latter issue in Section VII.B.4(c), infra.

658 Article 31(1) of the Vienna Convention provides that “[a] treaty shall be interpreted in good faith in accordance with the ordinary meaning to be given to the terms of the treaty in their context and in the light of its object and purpose.“

659 Paragraph 4.366, supra.

660 United States — Anti-Dumping Duty on Dynamic Random Access Semiconductors (DRAMs) of One Megabit or Above from Korea, WT/DS99/R, Report of the Panel adopted on 19 March 1999, paragraph 6.21.

661 It should be noted that footnote 1 to Article 1 of the SCM Agreement refers, inter alia, to the Illustrative List of Export Subsidies with respect to the issue when exemptions or remissions of duties and indirect taxes represent a subsidy within the meaning of Article 1. That footnote clearly is not applicable in the context of this dispute, which relates to issues of direct taxes.

662 Paragraph 4.472, supra. The European Communities continues to note, however, that “[t]he quoted sentence does not say or even imply that the exporting country has the right to exempt from tax income from an export transaction which would otherwise bear tax.“

663 Paragraph 4.699, supra.

789 As the Appellate Body explained in the context of “like product” analysis under Article III of GATT 1994, “[i]n applying the criteria cited in Border Tax Adjustments to the facts of any particular case … panels can only apply their best judgement in determining whether in fact products are “like”. This will always involve an unavoidable element of individual, discretionary judgement.” Japan — Taxes on Alcoholic Beverages, WT/DS8/11-WT/DS10/11-WT/DS11/8, Report of the Appellate Body adopted on 1 November 1996, pp. 20-21.

664 Paragraph 4.271, supra.

665 30 per cent or 15/23, in the case of a corporate shareholder. See US Internal Revenue Code, Section 291(a)(4).

666 Paragraph 4.1128, supra. The caveat “directly” is significant, in that the foreign-source income of a US-owned foreign corporation would be taxable either when distributed to the US parent or, in the case of the Sub-part F income of a controlled foreign corporation, as an imputed dividend whether or not distributed. This example demonstrates the importance of looking at the FSC exemptions as a package rather than separately.

667 Statement of Joseph H. Guttentag, International Tax Counsel, Department of the Treasury before the United States Senate, 21 July 1995, p. 12.

668 US Internal Revenue Code, Section 927(f).

669 Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, Tax Expenditures — Recent Experiences (Paris, 1996), p. 107 et seq.

671 US Department of Commerce, Foreign Sales Corporations — A Tax Incentive for Exporters, p. 1.

672 Paragraph 4.975, supra.

673 Description of Foreign Sales Corporation (FSC), Appendix A to the First Submission of the United States to the Panel, paragraph 1.

674 Ibid., paragraph 1.

675 Testimony of Joseph J. Guttentag, International Tax Counsel, Department of the Treasury, Before the Committee on Finance, US Senate, 21 July 1995, p. 10.

676 US Department of Commerce, Foreign Sales Corporations — A Tax Incentive for US Exporters.

677 Paragraph 4.364, supra.

678 Paragraph 4.363, supra.

679 Paragraph 4.366, supra.

680 Paragraph 4.382, supra (emphasis added).

681 Paragraph 4.639, supra. To the contrary, it could be observed — and not entirely in jest — that the most important provisions of the WTO Agreement are found in footnotes, and it is certainly not the case that language found in a footnote to the WTO Agreement is somehow subsidiary in legal terms to that found in the body of the Agreement.

682 The United States has not asserted that either of these provisions is relevant to this dispute.

683 Paragraph 4.378, supra.

684 European Communities — Measures Affecting the Importation of Certain Poultry Products, WT/DS69/AB/R, Report of the Appellate Body adopted on 23 July 1998, paragraph 83.

685 Paragraph 4.320, supra.

686 As the Appellate Body has stated, “Members of the WTO are free to pursue their own domestic policy goals through internal taxation or regulation so long as they do not do so in a way that violates Article III or any of the other commitments they have made in the WTO Agreement” (emphasis added). Japan — Taxes on Alcoholic Beverages, WT/DS8/AB/R-WT/DS10/AB/R-WT/DS11/AB/R, Report of the Appellate Body adopted on 1 November 1996, p. 16.

687 Paragraph 4.668, supra.

688 Paragraph 4.273, supra.

689 Paragraph 4.1083, supra.

690 Paragraphs 4.1131-4.1135, supra.

691 Paragraph 4.296, supra.

692 Paragraph 4.272.

693 The Appellate Body has explained that a panel should address those claims on which a finding is necessary in order to enable the DSB to make sufficiently precise recommendations and rulings so as to allow for prompt compliance by a Member with those recommendations and rulings “in order to ensure effective resolution of disputes to the benefit of all Members” as provided by Article 21.1 of the DSU. See Australia—Measures Affecting Importation of Salmon, WT/DS18/AB/R, Report of the Appellate Body adopted on 6 November 1998, paragraph 223.

694 The sole EC discussion of the consistency of this hypothetical scheme is comprised of a few sentences in its response to questions from the Panel after the second meeting, responses to which the United States has not had an opportunity to react. While vigorous argumentation is always important to ensure that a panel has before it all relevant considerations, this is particularly the case where legislation as complex as the US Internal Revenue Code is involved.

695 US Internal Revenue Code, Section 927(a)(l)(C).

696 See Section IV.C of this Report.

697 See supra, paragraph 7.127.

698 In this regard, it is perhaps no surprise that the arguments of the parties in this dispute focused on the European Communities’ Article 3.l(a) claim. Although the European Communities’ Article 3.1(b) claim clearly was not abandoned, the legal issues relating to that claim were not thoroughly explored by either party.

699 See, e.g., United States — Measure Affecting Imports of Woven Wool Shirts and Blouses from India, WT/DS33/AB/R, Report of the Appellate Body adopted on 23 May 1997, pp. 13-14.

700 Although the parties also disagree as to whether products which appear in a Member's schedule but at a zero level are subject to “reduction commitments”, none of the products in the US schedule are scheduled at a zero level. See Schedule XX — United States of America, Section II, Part IV. Accordingly, we need not decide whether products which are scheduled at a zero level are subject to “reduction commitments” within the meaning of Article 10.3.

701 The difficulties would be particularly great in cases where a number of different export subsidies are granted with respect to a product subject to some non-zero level of commitment. In this case, even if the complaining Member knew the quantity of exports benefiting from each export subsidy, it would not know whether the different export subsidies were being provided with respect to the same exports or whether different export subsidies were being provided with respect to distinct exports.

702 For instance, a measure which is listed as an export subsidy in Article 9.1 of the Agreement on Agriculture is an export subsidy for the purposes of the Agreement on Agriculture independently of the definition of subsidy in the SCM Agreement.

703 The United States argued that the term “subsidy” as used in the Agreement on Agriculture must be interpreted in light both of Article 1 of the SCM Agreement and Article XVI: 1 of GATT 1994. It is however the SCM Agreement, and not Article XVI of GATT 1994, that contains a definition of the term “subsidy”. Further, we have already rejected the United States’ arguments that the 1981 understanding is part of GATT 1994 or that, in any event, Article 1 must be interpreted in light of that understanding not to encompass the FSC scheme. Accordingly, we see no basis to consider that the 1981 understanding should control our interpretation of the term “subsidy” as used in the Agreement on Agriculture.

704 Webster's Third International Dictionary, Vol. II.

705 US Internal Revenue Code, Section 924(e).

706 The United States further suggests that, under the European Communities’ interpretation, Article 9.1(d) would apply to rebates of VAT. Value-added taxes, however, are not related primarily to marketing, but rather relate to the entire chain of production. In any event, the non-excessive rebate of VAT would of course not be a subsidy within the meaning of the SCM Agreement pursuant to footnote 1 to Article 1 of that Agreement, a conclusion we presume—but which we need not decide — would be equally applicable in the context of the Agreement on Agriculture.

707 The European Communities has not alleged that the FSC scheme represents an export subsidy listed in any other item of Article 9.1 of the Agreement on Agriculture. Consequently, although we do not preclude the possibility that the FSC scheme might also represent an Article 9.1 (a) export subsidy, we need not and do not resolve that question here.

708 The relevant data is summarised below: Source: Comext2 — Comtrade (HS).

709 In fact, the only evidence on the record relating to the use of FSC subsidies with respect to wheat indicates that, in 1992, twenty- seven FSC returns were filed with respect to “grains and soybeans”. Daniel S. Holick, Foreign Sales Corporations (1992), Table 1, EC exhibit 12.

710 The European Communities does not contend, in respect of scheduled products, that the availability of FSC subsidies — as opposed to their actual grant — represents the provision of export subsidies listed in Article 9 in excess of the United States’ reduction commitments and thus gives rise to a violation of the first limb Article 3.3 of the Agreement on Agriculture. To the contrary, the European Communities — in response to a question from the Panel — states that: “[g]iven the fact that there are agricultural products for which the US has a commitment of zero level the mandatory availability of FSC to any agricultural product (i.e. the fact that anybody who wants to export any agricultural product is entitled to FSC subsidies) is in itself a violation of Article 3 and 8.” We also recall that none of the products listed in the US schedule are scheduled at a zero level. Accordingly, we need not and do not decide this issue.

711 The New Shorter Oxford English Dictionary (1993), at p. 2393.

712 The provisions cited by the United States in this regard are: (a) the first limb of Article 3.3, which provides that a Member: “shall not provide export subsidies … in excess of the budgetary outlay and quantity commitment levels specified [in the Member's Schedule]“; (b) Article 9.2(a)(ii), which refers to: ”… the maximum quantity … in respect of which such export subsidies may be granted in that year.“; (c) Article 10.1, which states that: “Export subsidies not listed in paragraph 1 of Article 9 shall not be applied in a manner which results in, or which threatens to lead to, circumvention of export subsidy commitments;…“; and (d) Article 10.3, which refers to the need to ”… establish that no export subsidy … has been granted in respect of the quantity of exports in question”.

713 In respect of Article 10.3, please refer to our conclusion in paragraph 7.143 above that Article 10.3 applies only in the context of scheduled products.

714 In this respect, however, we note that the Shorter Oxford English Dictionary reflects a variety of definitions of the term “grant”, including: “3. An authoritative bestowal or conferring of a right, etc.; a gift or assignment of money, etc. out of a fund”. Further, it cannot simply be assumed a priori that Article 10.3 serves to define the scope of the first limb of Article 3.3, much less that it defines the scope of the second limb of that Article.

715 See footnote 710, supra.

716 In light of our finding that the FSC scheme is an export subsidy listed in Article 9.1 of the Agreement on Agriculture, we need not address the European Communities’ alternative claim under Article 10.1 of that Agreement.