No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

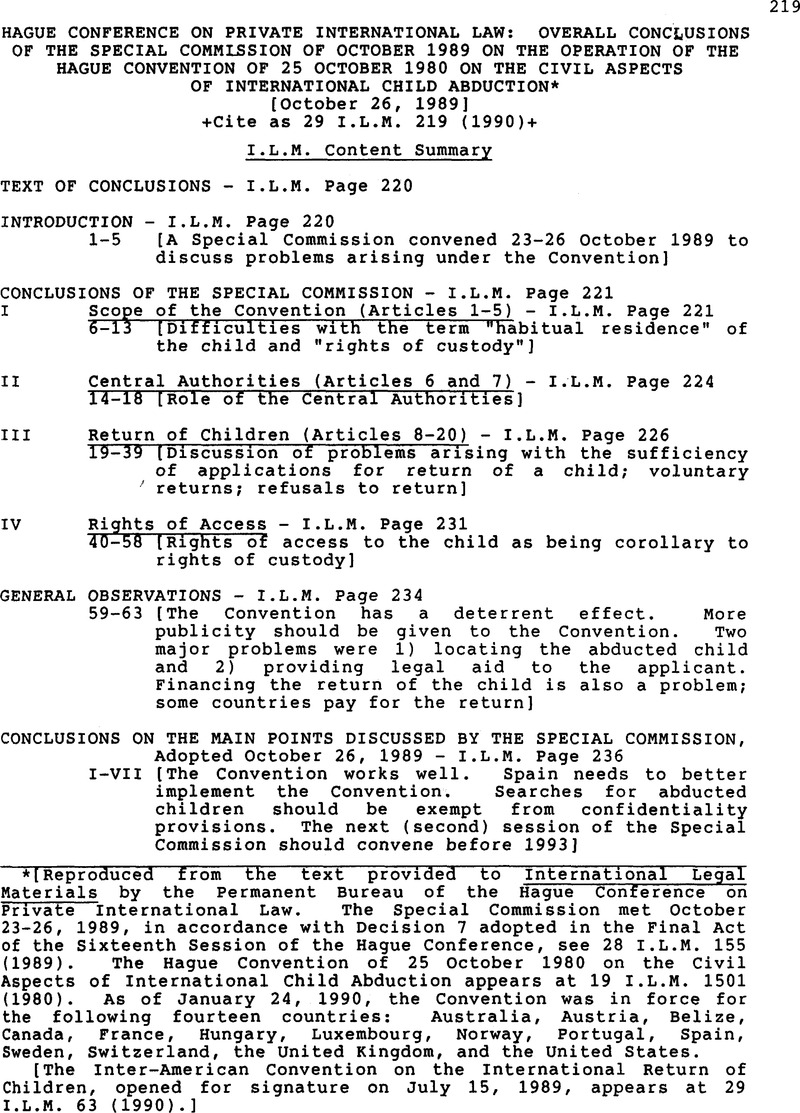

Hague Conference on Private International Law: Overall Conclusions of the Special Commission of October 1989 on the Operation of the Hague Convention of 25 October 1980 on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Reports

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1990

References

* Reproduced from the text provided to International Legal Materials by the Permanent Bureau of the Hague Conference on Private International Law. The Special Commission met October 23-26, 1989, in accordance with Decision 7 adopted in the Final Act of the Sixteenth Session of the Hague Conference, see 28 I.L.M. 155 (1989). The Hague Convention of 25 October 1980 on the Civil Aspects of International Child Abduction appears at 19 I.L.M. 1501 (1980). As of January 24, 1990, the Convention was in force for the following fourteen countries: Australia, Austria, Belize, Canada, France, Hungary, Luxembourg, Norway, Portugal, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

1 Affaire ward/baume, arrét du 23 mars 1989 (see Preliminary Document No 4, p.4).

2 Note by the Permanent Bureau.Compare the decision of the High Court (England) in the case of In re J.,(Abduction; Ward Of Court), [1989] 3 W.L.R., 825, The Weekly Law Reports, 20 October 1989, in which the child had been declared a “ward of court”,the mother had been granted care and control of the ward, and the father had been granted weekly access.The court held that, since the court had the right under English law to determine the child's place of residence, the court would (on application by the father) declare that the mother, by removing the child to the United States without the court's consent, had wrongfully removed the child within the meaning of Article 3 of the Hague Convention.

3 Note by the Permanent Bureau.It is relevant to this issue that the Convention never specifies that the “return” of the child is to be made to his or her habitual residence. This was intentional, since it was contemplated that the custodial parent might change habitual residences before return of the child could be achieved. However, it does not seem to have been specifically foreseen that a country might be asked under the Convention to enforce the custody decree entered by its own courts in order to send the child away from his or her place of habitual residence.

4 Note by the Permanent Bureau.In a few cases, courts have undertaken a broader enquiry into the merits of the cases and into the general interests of the child who had been abducted than seems to be justified by the more concrete criteria set out in Article 13 b,of the Convention. Here reference can be made to the decision of 13 July 1989 by the Court of Appeal of Lisbon, summarized in Preliminary Document No 2, at pages 64-65, and the decision of the Bezirksgericht Uster, (Switzerland) of 19 September 1989 set out (in German) in Preliminary Document No.2, Addendum I, at pages 90-107. In the great majority of cases from all countries, however, thecourtshave interpreted Article 13 b, strictly and have adhered closely to the spirit of the Convention.

5 Note by the Permanent Bureau.Information received during and after the October 1989 Special Commission meeting indicates that the opportunity for the personnel of Central Authorities designated under the Convention to meet each other in person and to engage in both formal and informal discussion of problems arising in practice has contributed to a greatly improved set of working relationships.