No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

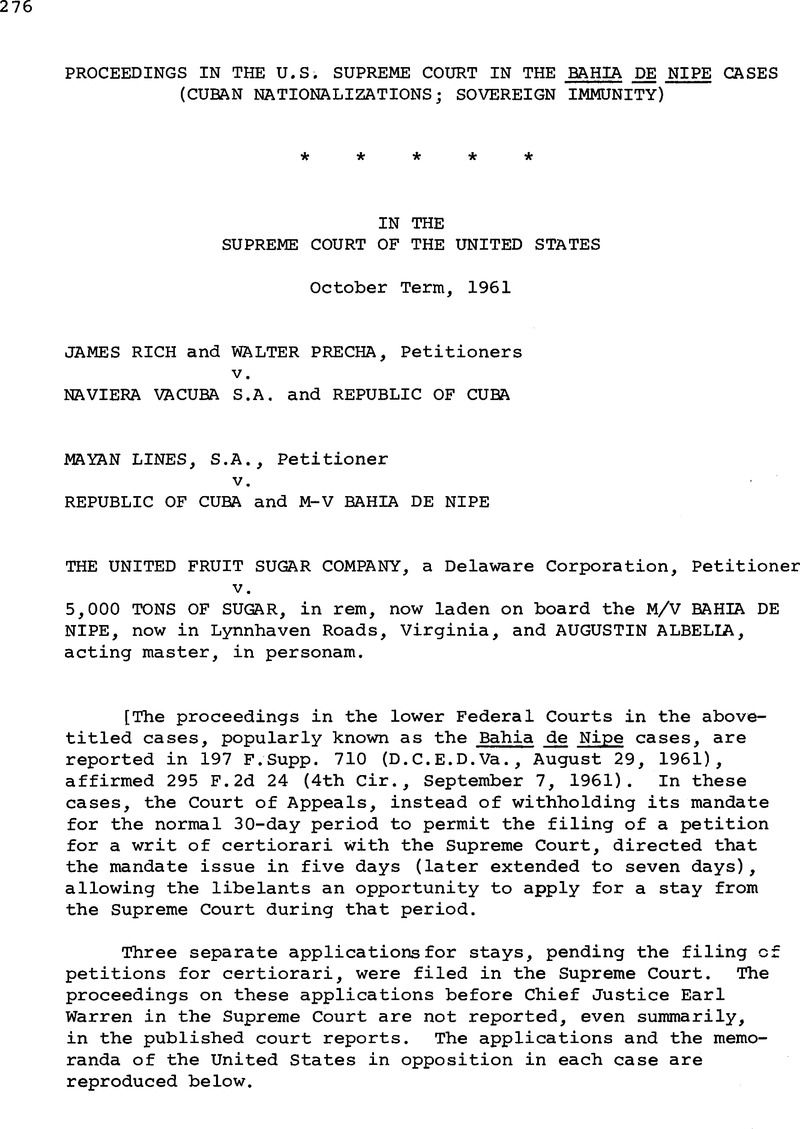

Proceedings in the U.S. Supreme Court in the Bahia de Nipe Cases (Cuban Nationalizations; Sovereign Immunity)

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 17 August 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Arbitral Decisions

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1962

References

page 279 note 1. See the case of Harris & Company Advertising, Inc. v. Republic of Cuba. 127 So. 2d 687 (Fla.), where the Cuban Government itself pleaded sovereign immunity and the State Department refused to recognize and allow the plea in that case.

page 279 note * [not reprinted here]

page 287 note 2. “Every judicial action exercising or relinquishing jurisdiction over the vessel of a foreign government has its effect upon our relations with that government.” Republic of Mexico v. Hoffman. 324 U.S. 30, at 35.

3. Moreover, we do not agree that the BAHIA DE NIPE was not in the possession of the Cuban Government; it was being operated for that government by one of its arms.

4. The certiorari petition appended to the stay application asserts a conflict between the ruling of the Fourth Circuit below and the decision of the Second Circuit, in 1941, in The Katinqo Hadjipatera. 119 F. 2d 1022, affirming on the opinion below, 40 F. Supp. 546 (S.D. N.Y.). There is no conflict. First, the Katinqo case was decided before Ex parte Peru and Mexico v. Hoffman were decided by this Court, and any intimations contrary to the principles of those opinions have been overruled. Second, in Katinqo the vessel was in the United States at the time the foreign government issued its requisition order, and it appeared that that government had never taken possession of the vessel; the status of property outside the sovereign's territorial jurisdiction when an attempt at seizure is made is quite different from property which is taken over by the foreign sovereign within its own territory. Third, our government's suggestion to the district court appears, so far as we can tell, to have been more limited than the suggestion of immunity in the present and not to have full outweight immunity for the vessel.

page 297 note 1. “* * * The clear weight of authority in this country, as well as that of England and Continental Europe, is against all seizures, even though a valid judgment has been entered. To so hold is not depriving our own courts of any attribute of jurisdiction. It is but recognizing the general international understanding, recognized by civilized nations, that a sovereign's person and property ought to be held free from seizure or molestation at all peaceful times and under all circumstances. Nor is this in derogation of the dignity owed to our courts.”

page 297 note 2. “Of course, the sovereign can consent that any judicial question can be determined by any court. But such consent is entirely voluntary, and it may withdraw its consent at any time.”

page 300 note * [not reprinted here]

page 302 note 1. The first application, in the Rich case, was filed on Saturday, September 9, 1961, and denied on Monday, September 11, 1961. The second application, in the Mayan Lines case, was filed on Monday and denied the following day. Both of those cases, together with the present United Fruit case, were consolidated and disposed of in a single order in the district court and in the same opinion in the court of appeals.

page 302 note * [Pages 280-291 of International Legal Materials]

page 303 note 2. The dissenting opinion in the case objected only to applying the act of state doctrine to defeat a counterclaim against the foreign sovereign where the foreign sovereign had deliberately invoked the jurisdiction of our courts. Cf. National City Bank v. Republic of China, 348 U.S. 356. The present claim against the cargo does not, of course, arise in any counterclaim situation and the considerations underlying the dissenting opinion as well as the Republic of China case thus have no application here.