No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

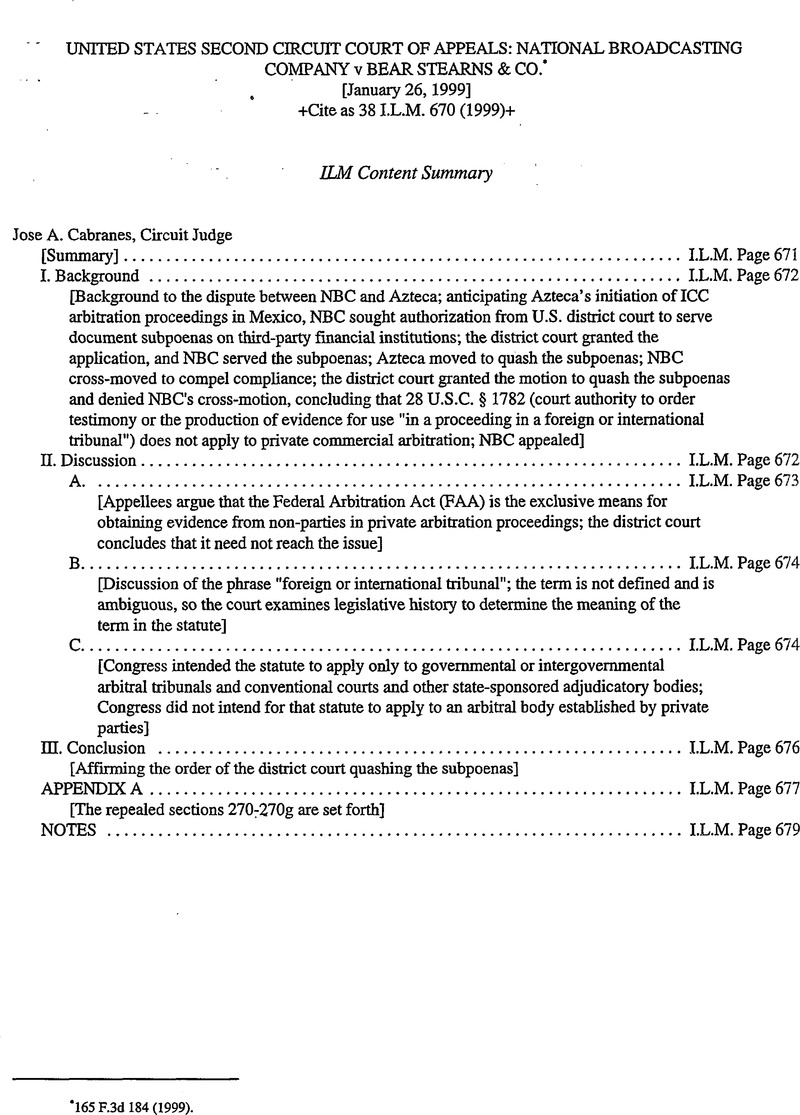

United States Second Circuit Court of Appeals: National Broadcasting Company v Bear Stearns & Co

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1999

Footnotes

165 F.3d 184 (1999).

References

[1] The Honorable Robert N.Chatigny, of the United States District Court for the District of Connecticut, sitting by designation.

[1] Section 1782 provides in relevant part that:The district court of the district in which a person resides or is found may order him to give his testimony or statement or to produce a document or other thing for use in a proceeding in a foreign or international tribunal, including criminal investigations conducted before formal accusation. The order may be made pursuant to a letter rogatory issued, or request made, by a foreign or international tribunal or upon the application of any interested person and may direct that the testimony or statement be given, or the document or other thing be produced, before a person appointed by the court. 28 U.S.C. § 1782(a).

[2] Bear Stearns & Co., Inc., Merrill Lynch & Company, Salomon Brothers, Inc. and SBC Warburg, Inc. are investment bankers for Azteca and Violy Byorum & Partners is Azteca's financial advisor. NBC also served a subpoena on Allen & Company, another of Azteca's investment bankers, but Allen & Company neither moved to quash nor produced documents. It indicated that it would abide by the decision of the court concerning the enforceability of the subpoenas.

[3] Section 7 reads as follows: The arbitrators selected either as prescribed in this title or otherwise, or a majority of them, may summon in writing any person to attend before them or any of them as a witness and in a proper case to bring with him or them any book, record, document, or paper which may be deemed material as evidence in the case. The fees for such attendance shall be the same as the fees of witnesses before masters of the United States courts. Said summons shall issue in the name of the arbitrator or arbitrators, or a majority of them, and shall be signed by the arbitrators, or a majority of them, and shall be directed to the said person and shall be served in the same manner as subpoenas to appear and testify before the court; if any person or persons so summoned to testify shall refuse or neglect to obey said summons, upon petition the United States district court for the district in which such arbitrators, or a majority of them, are sitting may compel the attendance of such person or persons before said arbitrator or arbitrators, or punish said person or persons for contempt in the same manner provided by law for securing the attendance of witnesses or their punishment for neglect or refusal to attend in the courts of the United States. 9 U.S.C. § 7.

[4] The version of § 1782 in effect prior to the 1964 revisions provided as follows: The deposition of any witness within the United States to be used in any judicial proceeding pending in any court in a foreign country with which the United States is at peace may be taken before a person authorized to administer oaths designated by the district court of any district where the witness resides or may be found. The practice and procedure in taking such depositions shall conform generally to the practice and procedure for taking depositions to be used in courts of the United States. 28 U.S.C. § 1782 (1958) (as reproduced in Hans Smit, Assistance Rendered by the United States in Proceedings Before International Tribunals, 62 Colum. L. Rev. 1264,1267 n.18 (1962)).

[5] Act of July 3,1930, ch. 851 §1-4,46 Stat. 1005,1006; and Acts of July 3,1930, ch. 851 §§ 5-8, as added June 7,1933, ch. 50,48 Stat. 117,118, repealed by Act of Oct. 3,1964, § 3,78 Stat. 995. See also Hans Smit, Assistance Rendered by the United States in Proceedings Before International Tribunals, 62 Colum. L. Rev. 1264,1266 n.17,1269 n.30,1270 n.31,1271 n.35,1273-74 n.48,1275 n.52 (1962) (reproducing statute). Because the repealed sections 270-270g are nowadays difficult to find, we set forth in Appendix A the pertinent provisions.

[6] In an article written more than three decades later, Professor Smit claims that § 1782, as amended in 1964, should be read to encompass private as well as governmental arbitration. Hans Smit, American Assistance to Litigation in Foreign and International Tribunals, 25 Syracuse J. Int'l L. & Com. 1,5 (1998). It is perhaps enough to say, in response, that Professor Smit's recent article does not purport to rely upon any special knowledge concerning legislative intent, and we find its reasoning unpersuasive. By contrast, statements in the 1962 article, which was specifically relied upon in the House and Senate reports, are probative of Congress's contemporaneous interpretation of the statutory language.

[7] If the statutory language unambiguously extended § 1782 to private arbitral tribunals, we would be reluctant to accord great weight to the legislative history's silence with respect to such entities. See Anderson v. Conboy, 156 F.3d 167,179 (2d Cir. 1998) (holding that references in legislative history to racial discrimination but not to alienage discrimination could not overcome statutory language clearly encompassing both categories). It seems inappropriate, in the circumstances presented, to read an ambiguous term so broadly that the statute effects a change in public policy which, if actually intended by Congress, very likely would have elicited at least some comment but did not do so.

[8] We acknowledge that because § 1782 does not apply to proceedings before private arbitrators, those who do not sit within the United States may face some difficulty in compelling evidence located here. See 9 U.S.C. § 7 (providing for compulsion of evidence by district court in district where arbitrators are sitting). Nevertheless, we consider this inconsistency to be less significant than that which would obtain from the contrary result

[9] For example, Professor Smit's most recent interpretation of the statute would have"tribunal" under § 1782 refer to "all bodies with adjudicatory functions." Hans.Smit, American Assistance to Litigation in Foreign and International Tribunals, 25 Syracuse J. Int'l L. & Com. 1,5 (1998). A tribunal would be international "when any of the parties before it, or any of the arbitrators, is not a citizen or resident of the United States"; and a tribunal would be foreign "when it is held anywhere outside the United States or is created under the law of a foreign country." Id. at 7-8. This understanding of the term "foreign or international tribunal" contains no discernible limits and could theoretically encompass even the most informal, unorthodox private dispute resolution proceedings. Further, it would produce anomalous results. For example, if the parties in a domestic arbitration simply appointed one foreign arbitrator to an otherwise entirely domestic panel dealing with a purely domestic dispute, that appointment would make § 1782 available to the parties where it otherwise would not be.