No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

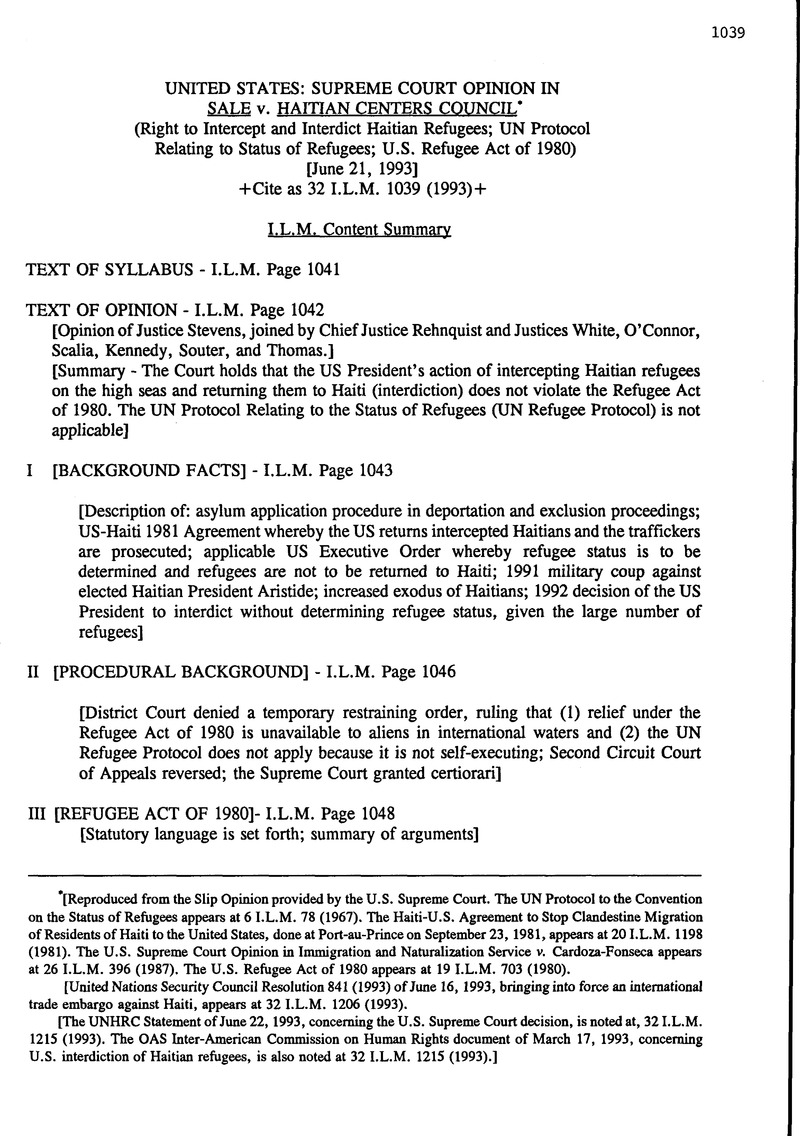

United States: Supreme Court Opinion in Sale V. Haitian Centers Council (Right to Intercept and Interdict Haitian Refugees; UN Protocol Relating to Status of Refugees; U.S. Refugee Act of 1980)

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 February 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1993

References

* [Reproduced from the Slip Opinion provided by the U.S. Supreme Court. The UN Protocol to the Convention on the Status of Refugees appears at 6 I.L.M. 78 (1967). The Haiti-U.S. Agreement to Stop Clandestine Migration of Residents of Haiti to the United States, done at Port-au-Prince on September 23, 1981, appears at 20 I.L.M. 1198 (1981). The U.S. Supreme Court Opinion in Immigration and Naturalization Service v. Cardoza-Fonseca appears at 26 I.L.M. 396 (1987). The U.S. Refugee Act of 1980 appears at 19 I.L.M. 703 (1980).

[United Nations Security Council Resolution 841 (1993) of June 16, 1993, bringing into force an international trade embargo against Haiti, appears at 32 I.L.M. 1206 (1993).

[The UNHRC Statement of June 22,1993, concerning the U.S. Supreme Court decision, is noted at, 32 I.L.M. 1215 (1993). The OAS Inter-American Commission on Human Rights document of March 17, 1993, concerning U.S. interdiction of Haitian refugees, is also noted at 32 I.L.M. 1215 (1993).]

1 This language appears in both Executive Order No. 12324, 3 CFR 181 (1981-1983 Comp.), issued by President Reagan, and Executive Order No. 12807, 57 Fed. Reg. 21133 (1992), issued by President Bush.

2 Title 8 U. S. C. § 1253(h) (1988 ed. and Supp. IV), as amended by § 203(e) of the Refugee Act of 1980, Pub. L. 96-212, 94 Stat. 107. Section 243(h)(l) provides: “(h) Withholding of deportation or return. (1) The Attorney General shall not deport or return any alien (other than an alien described in section 1251(a)(4)(D) of this title) to a country if the Attorney General determines that such alien's life or freedom would be threatened in such country on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion.” Section 243(hX2), 8 U. S. C. § 1253(h)(2), provides, in part: “(2) Paragraph (1) shall not apply tn any alien if the Attorney General determines that— “(D) there are reasonable grounds for regarding the alien as a danger to the security of the United States.” Before its amendment in 1965, § 243(h), 66 Stat. 214, read as follows: “The Attorney General is authorized to withhold deportation of any alien within the United States to any country in which in his opinion the alien would be subject to physical persecution on account of race, religion, or political opinion and for such period of time he deems to be necessary for such reason.” 8 U. S. C. § 1253(h) (1976 ed.); see also/TVS v. Stcvic, 467 U. S. 407, 414, n. 6(1984).

3 Jan. 31, 1967, 19 U. S. T. 6223, T. I. A. S. No. 6577.

4 8 U. S. C. § 1252 (1988 ed. and Supp. IV).

5 8U. S. C. § 1226. Although such aliens are located within the United States, the INA (in its use of the term exclusion) treats them as though they had never been admitted; § 1226(a), for example, says that the special inquiry officer shall determine “whether an arriving alien …shall be allowed to enter or shall be excluded and deported.” Aliens subject to either deportation or exclusion are eventually subjected to a physical act referred to as “deportation,” but we shall refer, as immigration law generally refers, to the former as “deportables” and the latter as “excludables.“

6 See INS v. Stevic, 467 U. S., at 423, n. 18.

7 Id., at 424-25; 426, n. 20.

8 As a part of that agreement, “the Secretary of State obtained an assurance from the Haitian government that interdicted Haitians would 'not be subject to prosecution for illegal departure.’ See Agreement, on Migrant(s)—Interdiction, Sept. 23,1981, United States-Haiti, 33 U. S. T. 3559, 3560, T. I. A. S. No. 10241.” See Department of State v. Ray, 502 U. S.,(1991) (slip op., at 3-4).

9 That proviso reflected an opinion of the Office of Legal Counsel that Article 33 of the United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees imposed some procedural obligations on the United States with respect to refugees outside United States territory. That opinion was later withdrawn after consideration was given to the contrary views expressed by the legal advisor to the State Department. See App. 202-230.

10 App. 231. In 1985 the District Court for the District of Columbia upheld the interdiction program, specifically finding that §243(h) provided relief only to Haitians in the United States. Haitian Refugee Center, Inc. v. Gracey, 600 F. Supp. 1396, 1406. On appeal from that holding, the Court of Appeals noted that “over 78 vessels carrying more than 1800 Haitians have been interdicted. The government states that it has interviewed all interdicted Haitians and none has presented a bona fide claim to refugee status. Accordingly, to date all interdictees have been returned to Haiti.” Haitian Refugee Center v. Gracey, 257 U. S. App. D. C. 367, 370, 809 F. 2d 794, 797 (1987). The Court affirmed the judgment of the District Court on the ground that the plaintiffs in that case did not have standing, but in a separate opinion Judge Edwards agreed with the District Court on the merits. He concluded that neither the United Nations Protocol nor § 253(h) was “intended to govern parties' conduct outside of their national borders… . The other best evidence of the meaning of the Protocol may be found in the United States’ understanding of it at the time of accession. There can be no doubt that the Executive and the Senate decisions to adhere were made in the belief that the Protocol worked no substantive change in existing immigration law At that time‘[t]hereliefauthorizedby§243(h)r8U. S. C. § 1253(h)] was not … available to aliens at the border seeking refuge in the United States due to persecution.'” Id., at 413-414, 809 F. 2d, at 840-841 (Edwards, J., concurring in part and dissenting in part).See INS v. Stevic, 467 U. S., at 415.

11 A “refugee” as defined in 8 U. S. C. § 1101(a)(42XA), is entitled to apply for a discretionary grant of asylum pursuant to 8 U. S. C. § 1158. The term “refugee” includes “any person who is outside any country of such person's nationality or, in the case of a person having no nationality, is outside any country in which such person last habitually resided, and who is unable or unwilling to return to, and is unable or unwilling to avail himself or herself of the protection of, that country because of persecution or a well-founded fear of persecution on account of race, religion, nationality, membership in a particular social group, or political opinion ….” Section 1158(a) provides: “The Attorney General shall establish a procedure for an alien physically present in the United States or at a land border or port of entry, irrespective of such alien's status, to apply for asylum, and the alien may be granted asylum in the discretion of the Attorney General if the Attorney General determines that such alien is a refugee within the meaning of section 1101(a)(42XA) of this title.” (Emphasis added.) This standard for asylum is similar, but not quite as strict as the standard applicable to a withholding of deportation pursuant to §243(h)(l). See generally, INS v. Cardoza-Fonseca, 480 U. S. 421(1987).

12 See App. 244-245.

13 Executive Order No. 12,807 reads in relevant part as follows: “Interdiction of Illegal Aliens “By the authority vested in me as President by the Constitution and the laws of the United States of America, including sections 212(0 and 215(a)(l) of the Immigration and Nationality Act, as amended (8 U. S. C. 1182(0 and 1185(a)(l), and whereas: “(1) The President has authority to suspend the entry of aliens coming by sea to the United States without necessary documentation, to establish reasonable rules and regulations regarding, and other limitations on, the entry or attempted entry of aliens into the United States, and to repatriate aliens interdicted beyond the territorial sea of the United States; “(2) The international legal obligations of the United States under the United Nations Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees (U. S. T.I.A.S. 6577; 19 U. S.T. 6223) to apply Article 33 of the United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees do not extend to persons located outside the territory of the United States; “(3) Proclamation No. 4865 suspends the entry of all undocumented aliens into the United States by the high seas; and “(4) There continues to be a serious problem of persons attempting to come to the United States by sea without necessary documentation and otherwise illegally; “I, GEORGE BUSH, President of the United States of America, hereby order as follows: “Sec. 2. (a) The Secretary of the Department in which the Coast Guard is operating, in consultation, where appropriate, with the Secretary of Defense, the Attorney General, and the Secretary of State, shall issue appropriate instructions to the Coast Guard in order to enforce the suspension of the entry of undocumented aliens by sea and the interdiction of any defined vessel carrying such aliens. “(c) Those instructions to the Coast Guard shall include appropriate directives providing for the Coast Guard: “(1) To stop and board defined vessels, when there is reason to believe that such vessels are engaged in the irregular transportation or persons or violations of United States law or the law of a country with which the United States has an arrangement authorizing such action. “(2) To make inquiries of those on board, examine documents and take such actions as are necessary to carry out this order. “(3) To return the vessel and its passengers to the country from which it came, or to another country, when there is reason to believe that an offense is being committed against the United States immigration laws, or appropriate laws of a foreign country with which we have an arrangement to assist; provided, however, that the Attorney General, in his unreviewable discretion, may decide that a person who is a refugee will not be returned without his consent. “(d) These actions, pursuant to this section, are authorized to be undertaken only beyond the territorial sea of the United States. “Sec. 5. This order shall be effective immediately. (s)George Bush to enter the United States and is necessary to protect the lives of the Haitians, whose boats are not equipped for the 600-mile sea journey. “The large number of Haitian migrants has led to a dangerous and unmanageable situation. Both the temporary processing facility at the U. S. Naval base Guantanamo and the Coast Guard cutters on patrol are filled to capacity. The President's action will also allow continued orderly processing of more than 12,000 Haitians presently at Guantanamo. “Through broadcasts on the Voice of America and public statements in the Haitian media we continue to urge Haitians not to attempt the dangerous sea journey to the United States. Last week alone eighteen Haitians perished when their vessel capsized off the Cuban coast. “Under current circumstances, the safety of Haitians is best assured by remaining in their country. We urge any Haitians who fear persecution to avail themselves of our refugee processing service at our Embassy in Port-au-Prince. The Embassy has been processing refugee claims since February. We utilize this special procedure in only four countries in the world- We are prepared to increase the American embassy staff in Haiti !Vii refugee processing if necessary.“ App. 327.

14 This decision was not based on agreement with the executive's policy. The District Court wrote: “On its face, Article 33 imposes a mandatory duty upon contracting states such as the United States not to return refugees to countries in which they face political persecution. Notwithstanding the explicit language of the Protocol and dicta in Supreme Court cases such as INS v. Cardoza Fonseca, 480 U. S. 421 (1987) and INS v. Stevic, 467 U. S. 407 (1984), the controlling precedent in the Second Circuit is Bertrand v. Sava which indicates that the Protocols’ provisions are not self-executing. See 684 F. 2d 204, 218 (2d Cir. 1982).

15 Section 101(a)(3), 8 U. S. C. §1101(a)(3), provides: “The term ‘alien’ means any person not a citizen or national of the United States.“

16 Before 1980, §243(h) distinguished between two groups of aliens: those ‘within the United States', and all others. After 1980, §243(h)(l) no longer recognized that distinction, although § 243(h)(2)(C) preserves it for the limited purposes of the ‘serious non political crime’ exception. The government's reading would require us to rewrite § 243(h)(l) into its pre-1980 status, but we may not add terms or provisions where congress has omitted them, see Gregory v. Afiheroft, [501 U. S., 1 (1991); West Virginia Univ. Hosps., Inc. v. Casey, 1499 U. S.,1 (1991), and this restraint is even more compelling when congress has specifically removed a term from a statute: ‘Few principles of statutory construction are more compelling than the proposition that Congress does not intend sub silentio to enact statutory language that it has earlier discarded.’ Nachman Corp. v. Pension Benefit Guaranty Corp., 446 U. S. 359, 392-93 … (1980) (Stewart,.1., dissenting) (quoted with approval in INS v. Cardoza-Fonseca, 480 U. S. at 442—43 …). ‘To supply omissions transcends the judicial function.’ Iselin v. United States, 270 U. S. 245, 250 … (1926) (Brandeis, J.).“ 969 F. 2d, at 1359.

17 The statute's location in Part V reflects its original placement there before 1980—when §243(h) applied by its terms only to ‘deportation'. Since 1980, however, § 243(h)(l) has applied to more than just ‘deportation'—it applies to ‘return’ as well (the former is necessarily limited to aliens ‘in the United States', the latter applies to all aliens). Thus, § 243, which applies to all aliens, regardless of whereabouts, has broader application than most other portions of Part V, each of which is limited by its terms to aliens In’ or ‘within’ the United States; but the fact that § 243 is surrounded by sections more limited in application has no bearing on the proper reading of § 243 itself.” Id., at 1360. 1

18 July 28, 1951, 19 U. S. T. 6259, T. I. A. S. No. 6577.

19 See INS v. Cardoza-Fonseca, 480 U. S. 421, 436-437 (1987). Although the United States is not a signatory to the Convention itself, in 1968 it acceded to the United Nation Protocol Relating to the Status of Refugees, which bound the parties to comply with Articles 2 through 34 of the Convention as to persons who had become refugees because of events taking place after January 1, 1951. See INS v. Stevic, 467 U. S., at 416. Because the Convention established Article 33, and the Protocol merely incorporated it, we shall refer throughout this opinion to the Convention, even though it is the Protocol that applies here.

20 “One of the considerations stated in the Preamble to the Convention is that the United Nations has ‘endeavored to assure refugees the widest possible exercise of … fundamental rights and freedoms.’ The government's offered reading of Article 33.1, however, would narrow the exercise of those freedoms, since refugees in transit, but not present in a sovereign area, could freely be returned to their persecutors. This would hardly provide refugees with the widest possible exercise’ of fundamental human rights, and would indeed render Article 33.1 ‘a cruel hoax.'” 969 F. 2d, at 1363.

21 The Netherlands, Belgium, The Federal Republic of Germany, Italy, Sweden, and Switzerland. See id.,at 1365.

22 Judge Newman concurred separately, id.,at 1368-1369, and Judge Walker dissented, noting that the 1980 amendment eliminating the phrase “within the United States” evidenced only an intent to extend the coverage of § 243(h) to exclusion proceedings because the Court had previously interpreted those words as limiting the section's coverage to deportation proceedings. Id.,at 1375-1377. See Leng May Ma v.Barber,357 U. S. 185, 187-189 (1958); see also Plyler v.Doe,457 U. S. 202, 212-213, n. 12(1982).

23 On November 30,1992, we denied the respondents’ motion to suspend briefing. 506 U. S

24 See 8 U. S. C. §§1104, 1105, 1153, 1201, and 1202 (1988 ed. and Supp. IV).

25 See 8 U. S. C. §§ 1157(a), (b), and (d); § 1182(0; §§ 1185(a) and (b); and § 1324a(d) (1988 ed. and Supp. IV).

26 See §§1161(a), (b), and (c) (Secretaries of Agriculture and Labor); § 1188 (Secretary of Labor); § 1421 (federal courts).

27 Title8U. S. C.§1182(f) provides: “Whenever the President finds that the entry of any aliens or of any class of aliens into the United States would be detrimental to the interests of the United States, he may by proclamation, and for such period as he shall deem necessary, suspend the entry of all aliens or any class of aliens as immigrant or non immigrants, or impose on the entry of aliens any restrictions he may deem to be appropriate.“

28 It is true that Executive Order 12807, 57 Fed. Reg. 23133, 23134 (1992), grants the Attorney General certain authority under the interdiction program (“The Secretary of the Department in which the Coast Guard is operating, in consultation, where appropriate, with the … Attorney General … shall issue appropriate instructions to the Coast Guard,” and “the Attorney General, in his unreviewable discretion, may decide that a person who is a refugee will not be returned without his consent“). Under the first phrase, however, any authority the Attorney General retains is subsidiary to that of the Coast Guard's leaders, who give the appropriate commands, and of the Coast Guard itself, which carries them out. As for the second phrase, under neither President Bush nor President Clinton has the Attorney General chosen to exercise those discretionary powers. Even if she had, she would have been carrying out an executive, rather than a legislative command, and therefore would not necessarily have been bound by §243(h)(l). Respondents challenge a program of interdiction and repatriation established by the President and enforced by the Coast Guard.

29 See, e.g., § 1158(a), quoted in n. 11, supra.

30 66 Stat. 214; see also n. 2, supra.

31 We conclude that petitioner's parole did not alter her status as an excluded alien or otherwise bring her ‘within the United States’ in the meaning of § 243(h).“ 357 U. S., at 186.

32 Even respondents acknowledge that §243(h) did not apply extra-territorially before its amendment. See Brief for Respondents 9, 12.

33 See H. R. Rep. No. 96-608, p. 30 (1979) (the changes “require … the Attorney General to withhold deportation of aliens who qualify as refugees and who are in exclusion as well as deportation, proceedings“); see also S. Rep. No. 96-256, p. 17 (1979).

34 “The President and the Senate believed that the Protocol was largely consistent with existing law. There are many statements to that effect in the legislative history of the accession to the Protocol. E.g., S. Exec. Rep. No. 14, 90th Cong., 2d Sess., 4 (1968) ('refugees in the United States have long enjoyed the protection and the rights which the protocol calls for’); id., at 6,7 ('the United States already meets the standards of the Protocol’); see also, id., at 2; S. Exec. K, 90th Cong., 2d Sess., III, VII (1968); 114 Cong. Rec. 29391 (1968) (remarks of Sen. Mansfield); id., at 27757 (remarks of Sen. Proxmire). And it was ‘absolutely clear’ that the Protocol would not ‘requir[e] the United States to admit new categories or numbers of aliens.’ S. Exec. Rep. No. 14, supra, at 19. It was also believed that apparent differences between the Protocol and existing statutory law could be reconciled by the Attorney General in administration and did not require any modification of statutory language. See e.g., S. Exec. K, supra, at VIII.” INS v. Stevic, 407 U. S., at 417-418.

35 U. S. Const., Art. VI, cl. 2 provides: “This Constitution, and the Laws of the United States which shall be made in Pursuance thereof; and all Treaties made, or which shall be made, under the Authority of the United States, shall be the supreme Law of the Land; …” In Murray v. The Charming Betsy, 2 Cranch 64, 117-118 (1804), Chief Justice Marshall wrote that “an act of congress ought never to be construed to violate the law of nations if any other possible construction remains … .” See also Weinberger v.Rossi, 456U. S. 25, 32(1982); Clark v. Allen, 331 U. S. 503, 508-511 (1947); Cook v. United States, 288 U. S. 102, 118-120 (1933)

36 Although the parallel provision in § 243(h)(2)(D), 8 U. S. C. § 243(h)(2)(D), that was added to the INA in 1980 does not contain the “country in which he is” language, the general understanding that it was intended to conform the statute to the Protocol leads us to give it that reading, particularly since its text is otherwise so similar to Article 33(2). It provides that §243(h)(l) “shall not apply” to an alien if the Attorney General determines that “there are reasonable grounds for regarding the alien as a danger to the security of the United States.” Thus the statutory term “security of the United States” replaces the Protocol's term “security of the country in which he is.” The parallel surely implies that for statutory purposes “the United States” is “the country in which he is.“

37 The New Cassell's French Dictionary 440 (1973), gives this translation: “return (I) [n'ts:n], v.i. Revenir(to comeback); retourner (to go back); rentrer (to come in again); répondre, répliquer (to answer). To return to the subject, revenir au sujet, (fam.) revenir à ses moutons.—u.t. Rendre (to give back); renvoyer (to send back); rembourser (to repay); rapporter (interest); répondre à; réndre compte (to render an account of); élire (candidates). He was returned, il fut élu; the money returns interest, largent rapporte intérêt; to return good for evil, rendre le bien pour le mal.—n. Retour (coming back, going back), TO.; rentrée (coming back in), /.; renvoi (sending back), m.; remise en place (putting back), f; profit, gain (profit), TO.; restitution (restitution), /.; remboursement (reimbursement), M.; élection (election), f.\ rapport, compte rendu, relevé, état (report); (Comm. montant des opérations, montant des remises; bilan (of a bank), m.; (pl.) produit, M. By return of post, par retour du courrier; in return for, en retour de; nil return, état néant, m.; on my return, au retour, comme je revenais chez moi; on sale or return, en dépôt, en commission; return address, addrese de l'éxpediteur,/.; return home, retour au foyer,m.; return journey, retour, m.; return match, revanche, f; return of casualties, état des pertes, m.; small profits (and) quick returns, petits profits, vente rapide; the official returns, les releves officiels, m.pl.; to make some return for, payer de retour.” Although there are additional translations in the Larousse Modern French-English Dictionary 545 (1978), “refouler” is not among them.

38 refouler [rrfiile], v.t. To drive back, to back (train etc.); to repel; to compress; to repress, to suppress, to inhibit; to expel (aliens); to refuse entry; to stem (the tide); to tamp; to tread (grapes etc.) again; to full (stuffs) again; to ram home (the charge in a gun). Refouler la marée, to stem, to go against the tide.—v.i. To ebb, to flow back. La marée refoule, the tide is ebbing.“ Cassell's, at 627. “refouler [-le] v. tr. (1). To stem (la marée). || NAUT. To stem (un courant). || TECHN. To drive in (une cheville); to deliver (1'eau); to full (une étoffe); to compress (un gaz); to hammer, to fuller (du métal). || MILIT. To repulse (une attaque); to drive back, to repel (l'ennemi); to ram home (un projectile). || PHILOH. To repress (un instinct). || CH. DE F. To back (un train). || Fl(i. To choke back (un sanglot). —v. intr. To flow back (foule); to ebb, to be on the ebb (marée). || MED. Refoule, inhibited.“ Larousse, at 607.

39 Under Article 33, after all, a nation is not prevented from sending a threatened refugee back only to his homeland, or even to the country that he has most recently departed; in some cases Article 33 would even prevent a nation from sending a refugee to a country where he had never been. Because the word “return,” in its common meaning, would make no sense in that situation (one cannot return, or be returned, to a place one has never been), we think it means something closer to “exclude” than “send back.“

40 See, e. g. ,N. Robinson, Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees: Its History, Contents and Interpretation 162-163 (1953) (“The Study on Statelessness [,U. N. Dept. of Social Affairs 60 (1949),! defined ‘expulsion’ as ‘the juridical decision taken by the judicial or administrative authorities whereby an individual is ordered to leave the territory of the country’ and ‘reconduction’ fwhich is the equivalent of ‘refoulement’ and was changed by the Ad Hoc Committee to the word ‘return’) as ‘the mere physical act of ejecting from the national territory a person residing therein who has gained entry or is residing regularly or irregularly.'… Art. 33 concerns refugees who have gained entry into the territory of a Contracting State, legally or illegally, but not to refugees who seek entrance into [the] territory“); 2 A. Grahl-Madsen, The Status of Refugees in International Law 94 (1972) (“\Non-refoulemeni] may only be invoked in respect of persons who are already present—lawfully or unlawfully—in the territory of a Contracting State. Article 33 only prohibits the expulsion or return ﹛refoulement) of refugees to territories where they are likely to suffer persecution; it does not obligate the Contracting State to admit any person who has not already set foot on their respective territories“). A more recent work describes the evolution of non-refoule-ment into the international (and possibly extraterritorial) duty of nonreturn relied on by respondents, but it also admits that in 1951 non-refoulement had a narrower meaning, and did not encompass extraterritorial obligations. Moreover, it describes both “expel” and “return” as terms referring to one nation's transportation of an alien out of its own territory and into another. See G. Goodwin-Gill, The Refugee in International Law 74-76(1983). Even the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees has implicitly acknowledged that the Convention has no extraterritorial application. While conceding that the Convention does not mandate any specific procedure by which to determine whether an alien qualifies as a refugee, the “basic requirements” his office has established impose an exclusively territorial burden, and announce that any alien protected by the Convention (and by its promise of non-refoulement) will be found either “'at the border or in the territory of a Contracting State.'” Office of United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Handbook on Procedures and Criteria for Determining Refugee Status 46 (Geneva, Sept. 1979) (quoting Official Records of the General Assembly, Thirty-second Session, Supplement No. 12 (A/32/12/Add.l), paragraph 53(6)(e)). Those basic requirements also establish the right of an applicant for refugee status “'to remain in the country pending a decision on his initial request.'” (emphasis added). Handbook on Refugee Status, at 460.

41 The Convention's failure to prevent the extraterritorial reconduction of aliens has been generally acknowledged (and regretted). See Aga Khan, Legal Problems Relating to Refugees and Displaced Persons, in Hague Academy of Int'l Law, 149 Recueil des Cours, 287, 318 (1976) (“Does the non-refoulement rule …apply…only to those already within the territory of the Contracting State? … There is thus a serious gap in refugee law as established by the 1951 Convention and other related instruments and it is high time that this gap should be filled“); Robinson, Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, at 163 (“fl]f a refugee has succeeded in eluding the frontier guards, he is safe; if he has not, it is his hard luck. It cannot be said that this is a satisfactory solution of the problem of asylum“); Goodwin-Gill, The Refugee in International Law, at 87 (“A categorical refusal of disembarkation cannot be equated with breach of the principle of non-refoulement, even though it may result in serious consequences for asylum-seekers“)

42 Conference of Plenipotentiaries on the Status of Refugees and Stateless Persons, Summary Record of the Sixteenth Meeting, U. N. Doc. A/CONF.2/SR.16, p. 6 (July 11, 1951)

43 Conference of Plenipotentiaries on the Status of Refugees and Stateless Persons, Summary Record of the Thirty-fifth Meeting, U. N. Doc. A/CONF.2/SR.35, at 21-22 (July 25, 1951).

44 The Swiss delegate's statement strongly suggests, moreover, that at least one nation's accession to the Convention was conditioned on this understanding

1 United Nations Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees, July 28, 1951, 19 U. S.T. 6259, 189 U.N.T.S. 150. Because the Protocol to which the United States acceded incorporated the Convention's Article 33,1 shall follow the form of the majority, see ante, at 12, n. 19, and shall refer throughout this dissent (unless the distinction is relevant) only to the Convention.

2 This Court has recognized that Article 33 has independent force. See, e.g., INS v. Stevic, 467 U. S., at 428, n. 22 (1984) (By modifying his discretionary practice, Attorney General “ ‘implemented'” and “honor[ed]” the Protocol's requirements). Because I agree with the near-universal understanding that the obligations imposed by Treaty and the statute are coextensive, I do not find it necessary to rely on the Protocol standing alone. As the majority suggests, however, ante, at 22, to the extent that the Treaty is more generous than the statute, the latter should not be read to limit the former

3 See, e.g., 5 Op. Off. Legal Counsel 242, 248 (1981) (under proposed interdiction of Haitian flag vessels, “^Individuals who claim that they will be persecuted …must be given an opportunity to substantiate their claims” under the Convention); United States as a Country of Mass First Asylum: Hearing Before the Subcommittee on Immigration and Refugee Policy of the Senate Committee on the Judiciary, 97th Cong., 1st Sess., 208-209 (1981) (letter from Office of Attorney General stating: “Aliens who have not reached our borders (such as those on board interdicted vessels) are … protected … by the U.N. Convention and Protocol“); id., at 4 (statement by Thomas O. Enders, Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs, regarding the Haitian interdiction program: “I would like to also underscore that we intend fully to carry out our obligations under the U.N. Protocol on the status of refugees“

4 The Court seems no more convinced than I am by the Government's argument that “refouler” is best translated as “expel.” See Brief for Petitioners 38-39. That interpretation, as the Second Circuit observed, would leave the treaty redundantly forbidding a nation to “expel” or “expel” a refugee. Haitian Centers Council, Inc. v. McNary, 969 F. 2d 1350, 1363 (1992

5 I am surprised by the majority's apparent belief that (a) the translations of“refouler” are of uncertain relevance (“To the extent that they are relevant, these translations imply …“), and (b) the term “refouler” is pertinent only as an aid to understanding the meaning of the English word “return” (“these translations imply that ‘return’ means …“). Ante at 25. The first assumption suggests disregard for the basic rule that consideration of a treaty's ordinary meaning must be the first step in its interpretation. The second assumption, by neglecting to treat the term “refouler” as significant in and of itself, overlooks the fact that under Article 46 the French and English versions of the Convention's text are equally authoritative.

6 In proceedings prior to that at which van Boetzelaer made his remarks, the Ad Hoc Committee delegates from France, Belgium, and the United Kingdom had made clear that the principle of non-refoulement, which existed only in France and Belgium did proscribe the rejection of refugees at a country's frontier. Ad Hoc Committee on Statelessness and Related Problems, Summary Record of the Twenty-First Meeting, U.N. Doc. E/AC.32/SR.21, pp. 4-5 (1950). Consistent with the United States’ historically strong support of non return, the United States delegate to the Committee, Louis Henkin, confirmed this: “Whether it was a question of closing the frontier to a refugee who asked admittance, or of turning him back after he had crossed the frontier, or even of expelling him after he had been admitted to residence in the territory, the problem was more or less the same. “Whatever the case might be … he must not be turned back to a country where his life or freedom could be threatened. No consideration of public order should be allowed to overrule that guarantee, for if the State concerned wished to get rid of the refugee at all costs, it could send him to another country or place him in an internment camp.” Ad Hoc Committee on Statelessness and Related Problems, Summary Record of the Twentieth Meeting, U.N. Doc. E/AC.32/SR.20, I'll 54 and 55, pp. 11-12 (1950). Speaking next, the Israeli delegate to the Ad Hoc Committee concluded: “The Committee had already settled the humanitarian question of sending any refugee … back to a territory where his life or liberty might be in danger.” Id., at 161, p. 13

7 See, e. g., A/Conf.2/SR.35, at 22 (“adopting] unanimously” the proposal to place the word “refouler” alongside the word “return“; ibid. (“adopt[ing] unanimously” the suggestion that the words “membership of a particular social group” be inserted); ibid, (“agreeing]” to changes in the actual wording of Article 33).

8 The majority also cites secondary sources that, it claims, share its reading of the Convention. See ante, at 26, nn. 40 and 41. Not one of these authorities suggests that any signatory nation sought to reserve the right to seize refugees outside its territory and forcibly return them to their persecutors. Indeed, the first work cited explains that the entire reason for the drafting of Article 33 was “the consideration that the turning back of a refugee to the frontiers of a country where his life or freedom is threatened on account of race or similar grounds would be tantamount to delivering him into the hands of his persecutors.” N. Robinson, Convention Relating to the Status of Refugees: Its History, Contents and Interpretation 161 (1953). These sources emphasize instead that nations need not admit refugees or grant them asylum—questions not at issue here. See, e.g., 2 A. Grahl-Madsen, The Status of Refugees in International Law 94 (1972) (“Article 33 only prohibits the expulsion or return (rcfoulement) of refugees to territories where they are likely to suffer persecution; it does not obligate the Contracting States to admit any person who has not already set foot on their respective territories“) (emphasis added); Goodwin-Gill, The Refugee in International Law 87 (“A categorical refusal of disembarkation cannot be equated with breach of the principle of non-refbulement, even though it may result in serious consequences for asylum-seekers“) (emphasis added); Aga Khan, Legal Problems Relating to Refugees and Displaced Persons, in Hague Academy of Int'l Law, 149 Recuil des Cours 287, 318 (1976) (“Does the non-refoulement rule thus laid down apply to refugees who present themselves at the frontier or only to those who are already within the territory of the Contracting State? …. It is intentional that the Convention fails to mention asylum as a right which the contracting States would undertake to grant to a refugee who, presenting himself at their frontiers, seeks the benefit of it …. There is thus a serious gap in refugee law as established by the 1951 Convention and other related instruments and it is high time that this gap should be filled“) (emphasis added). The majority also cites incidental territorial references in the 1979 Handbook on Procedures and Criteria for Determining Refugee Status as “implici[t] acknowledgement]” that the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees subscribes to their view that the Convention has no extraterritorial application. The majority neglects to point out that the current High Commissioner for Refugees acknowledges that the Convention does apply extraterritorially. See Brief for United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees as Amicus Curiae

9 The Executive Order at issue cited as authority 8 U. S. C. § 1182(0, which allows the President to restrict or “for such period as he shall deem necessary, suspend the entry of all aliens or any class of aliens as immigrant or non immigrants.” The Haitians, of course, do not claim a right of entry. Indeed, the very invocation of this section in this context is somewhat of a stretch. The section pertains to the President's power to interrupt for as long as necessary legal entries into the United States. Illegal entries cannot be “suspended”—they are already disallowed. Nevertheless, the Proclamation on which the Order relies declares, solemnly and hopefully: ‘The entry of undocumented aliens from the high seas is hereby suspended … .” Presidential Proclamation No. 48G5, 46 Fed. Reg. 48,107 (1981)

10 Of course the Attorney General's authority is not dependent on its recognition in the Order.

11 “[T]he Attorney General, in his unreviewable discretion, may decide that a person who is a refugee will not be returned without his consent.”

12 The word “return” is used throughout the INA; in no instance is there any indication that the word has a specialized meaning. See, e.g., 8 U. S. C. §§ 1101(a)(27)(A) (“special immigrant” is one lawfully admitted “who is returning from a temporary visit abroad“); 1101(a)(42)(A) (“refugee” is a person outside his own country who is “unable or unwilling to return to” his country because of persecution); 1182(a)(7)(B)(i)(I) (non immigrant who does not possess passport authorizing him “to return to country from which” he came is excludable); 1252 (deportable alien's parole may be revoked and the alien “returned to custody“); 1353 (travel expenses will be paid for INS officers who “become eligible for voluntary retirement and return to the United States“). It is axiomatic that “identical words used in different parts of the same act are intended to have the same meaning.” Atlantic Cleaners & Dyers, Inc. v. United States, 286 U. S. 427, 433 (1932).

13 Indeed, reasoning backwards, the majority actually looks to the American scheme to illuminate the Treaty. See ante, at 24

14 For this reason, the majority is mistaken to find any significance in the fact that the ban on return is located in the Part of the INA that deals as well with the deportation and exclusion hearings in which requests for asylum or for withholding of deportation “are ordinarily advanced.” Ante, at 17.

15 Congress used the words “physically present within the United States” to delimit the reach not just of § 208 but of sections throughout the INA. See, e.g., 8 U. S. C. §§ 1159 (adjustment of refugee status); 1101(a)(27)(I) (defining “special immigrant” for visa purposes); 1254(a)(l)-(2) (eligibility for suspension of deportation); 1255a(a)(3) (requirements for temporary resident status); 1401(d),(e),(g) (requirements for nationality but not citizenship at birth); 1409(c) (requirements for nationality status for children born out of wedlock); 1503(b) (requirement for appeal of denial of nationality status); and 1254a(c)(l)(A)(i), (c)(3)(B) (1988 ed., Supp. IV) (requirements for temporary protected status). The majority offers no hypothesis for why Congress would not have done so here as well.

16 Even if the majority's LengMay Ma proposition were correct, it would not support today's result. Leng May Ma was an excludable alien who had been in custody but was paroled into the United States. The Court determined that her parole did not change her legal status, and therefore that her case should be analyzed as if she were still “in custody.” The Court then explained that “the detention of an alien in custody pending determination of his admissibility does not legally constitute an entry though the alien is physically within the United States,” and stated: “It seems quite clear to us that an alien so confined would not be ‘within the United States’ for purposes of § 243(h).” 357 U. S., at 188. Lerig May Ma stands for the proposition that aliens in custody who have not made legal entries—including, but not limited to, those who are granted the privilege of parole—are legally outside the United States. According to the majority, Congress deleted the territorial reference in order to extend protection to such aliens. By the majority's own reasoning, then, § 243(h) applies to unadmitted aliens held in U. S. custody. That, of course, is exactly the position in which the interdicted Haitians find themselves.

17 Indeed, petitioners are hard-pressed to argue that restraints on the Coast Guard infringe upon the Commander-in-Chief power when the President himself has placed that agency under the direct control of the Department of Transportation. See Declaration of Admiral Leahy, App. 233.