No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

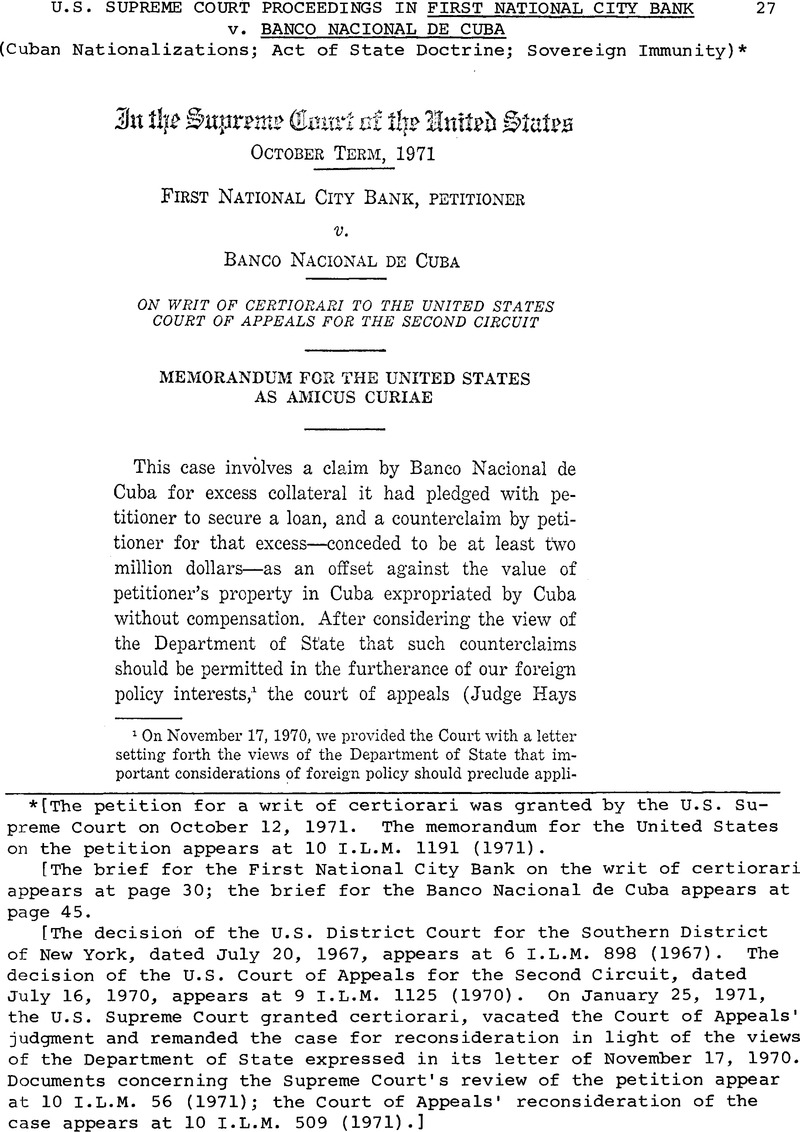

U.S. Supreme Court Proceedings in First National City Bank v. Banco Nacional de Cuba (Cuban Nationalizations; Act of State Doctrine; Sovereign Immunity)*

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 20 March 2017

Abstract

- Type

- Judicial and Similar Proceedings

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © American Society of International Law 1972

Footnotes

[The petition for a writ of certiorari was granted by the U.S. Supreme Court on October 12, 1971. The memorandum for the United States on the petition appears at 10 I.L.M. 1191 (1971).

[The brief for the First National City Bank on the writ of certiorari appears at page 30; the brief for the Banco Nacional de Cuba appears at page 45.

[The decision of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York, dated July 20, 1967, appears at 6 I.L.M. 898 (1967). The decision of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit, dated July 16, 1970, appears at 9 I.L.M. 1125 (1970). On January 25, 1971, the U.S. Supreme Court granted certiorari, vacated the Court of Appeals’ judgment and remanded the case for reconsideration in light of the views of the Department of State expressed in its letter of November 17, 1970. Documents concerning the Supreme Court’s review of the petition appear at 10 I.L.M. 56 (1971); the Court of Appeals’ reconsideration of the case appears at 10 I.L.M. 509 (1971).]

References

1 On November 17, 1970, we provided the Court with a letter setting forth the views of the Department of State that important considerations of foreign policy should preclude application of the act of state doctrine to cases like the instant one. See Memorandum submitted by the Solicitor General in First National City Bank v. Banco Nacional De Cuba, No. 846, O.T., 1970. On January 25,1971, the Court granted certiorari, vacated the judgment and remanded the case to the court of appeals “for reconsideration in light of the views of the Department of State” as set forth in that letter. 400 U.S. 1019. The letter is appended to the petition (Pet. App. C).

2 The act of state doctrine is an exception to the basic principle that United States courts adjudicate cases and controversies including those involving the application of international law “as often as questions of right depending upon it are duly presented for their determination.” The Paquete Habana, 175 U.S. 677, 700.

3 As the district court pointed out, there “is no serious question that the Government of Cuba and Banco. Nacional are one and the same for purposes of this litigation” (Pet. App. E4).

* The district court found that “There is no serious question that the Government of Cuba and Banco National are one and the same for purposes of this litigation”. (Appendix (“A.”), p. 37) Respondent “at various times has argued that defendant’s (petitioner’s) claim against the Cuban government cannot be asserted against Banco National, an entirely separate entity”. (A. p. 37, n. 3) This argument was renewed on appeal, but the court below did not pass on it.

1 E.g., Banco Nacional de Cuba v. Fair, 383 F.2d 166 (2d Cir. 1967) cert. den. 390 U.S. 956; Bernstein v. N.V. Nederlandsche-Amerikaansche, etc., 210 F.2d 375 (2d Cir. 1954) ; Stevenson Letter, 10 Int’l Legal Mat. 89 (1971) (A. p. 82) ; Hickenlooper Amendment, 22 U.S.C. § 2370(e) (2) (infra, p. 2a) ; Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. v. Jaffrate, [1953] 1 YV.L.R. 246 (The Rose Mary). As hereafter shown, infra pp. 11-15, these exceptions are applicable to this case.

2 Banco National de Cuba v. Sabbatino, 376 U.S. 398 (1964); United States v. Pink, 315 U.S. 203 (1942) ; United States v. Belmont, 301 U.S. 324 (1936) ; Shaplcigh v. Mier, 299 U.S. 468 (1937) ; Ricaud v. American Metal Co., 246 U.S. 304 (1918); Octjen v. Central Leather Co., 246 U.S. 297 (1918) ; The Santissima Trinidad, 7 Wheat. 283 (1822); L’Invincible, 1 Wheat. 238 (1816); The Schooner Exchange v. McFaddon, 7 Cranch 116 (1812); Hudson v. Guesticr, 4 Cranch 293 (1808) ; Ware v. Hylton, 3 Dall. 199 (1796) ; see 376 U.S., at 416, 417.

3 American Banana Co. v. United Fruit Co., 213 U.S. 347 (1909) and Underhill v. Hernandez, 168 U.S. 250 (1897) did not involve title to property, nor a defaulted obligation of a foreign sovereign, nor was a foreign sovereign a party in either case.

4 Admittedly, it denies effect to Cuba’s failure and presumed refusal to pay for what it took, but that was the consequence in Republic of China, and respondent itself has said “There may be some question as to whether a simple failure to meet a debt, unaccompanied by any specific act or repudiation, constitutes an Act of State. . . .” Brief in Opposition to Second Petition for Certiorari, p. 11, n. 9.

5 Sec Lillich, , International Law, 1970 Survey of New York Law, * 22 Syracuse L. Rev. 269-80 (1971)Google Scholar; Note, , 11 Va. J. Int’l L. 406 (1971)Google Scholar ; Malawer, , The Act of State Doctrine and the City Bank Case: A Proper Role for the Judiciary in the World Public Order, * 1 Bait. L. Rev. 70 (1971)Google Scholar.

6 Accord, Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. v. Jaffrate, [1953] 1 W.L.R. 246 (The Rose Mary).

7 In Isbrandtsen Tankers, Inc. v. President of India, 446 F.2d 1198 (2d Cir. 1971) the Second Circuit affirmed the role of the State Department in determining whether or not a given sovereign could be held responsible for its obligations. In President of India, it was held that the suggestion of immunity by the Department of State overrode the sovereign’s otherwise applicable waiver of immunity, citing Victory Transport, Inc. v. Comisaria General. 336 F.2d 354 (2d Cir. 1964). cert. den. 381 U.S. 934 (1965), and National City Bank of New York v. Republic of China, 348 U.S. 356 (1955). Also see Heaney v. Government of Spain, 445 F.2d 501 (2d Cir. 1971). In neither President of India nor Heaney did the court below cite this case.

8 E.g. Banco Nacional de Cuba v. The Chase Manhattan Bank, S.D.N.Y., 60 Civ. 4663; see A. p. 34.

9 In Pons v. Republic of Cuba, 294 F.2d 925 (D.C. Cir. 1961), cert. den. 368 U.S. 960 (1962), the court did not reach the merits because the counterclaim was asserted by a Cuban national, who was not entitled, as against his own government, to raise any claim based on violation of international law or of Cuban law. (See A. p 38, n. 4) Nonetheless, then Circuit Justice Burger was moved to say, in dissent, that I do not think we should carry the act of state doctrine to

the point where we permit a foreign state to come into our courts as a suitor and secure equitable relief on better or different terms than those available to an American litigant in the same courts.

10 Although respondent, in its briefs below, has denied the universality of this proposition, the great weight of authority holds that governmental seizure of property requires the payment of fair compensation. Some commentators maintain that the sovereign obligation does not extend beyond payment of some compensation or even beyond provision for deferred payment; Friedman, Expropriation in International Law, 206 (1953); Dawson & Weston, “Prompt, Adequate and Effective”: A Universal Standard of Compensation?, 30 Ford. L. Rev. 727 (1962) ; compare Fachiri, Expropriations & International Law, [1925] Brit. Y. B. Int’l L. 15, with Williams, International Law and the Property of Aliens [1928] Brit. Y. B. Int’l L. 1 ; cf. Sabbatino, 376 U. S., at 428, n. 26, 429 n. 31, 430 n. 32, but sec 430 n. 34. The United States has never regarded as persuasive those isolated instances in which confiscators or their apologists have declined to be bound by any requirement of compensation, or have urged, in furtherance of their immediate political purposes, that the established rule be abrogated. Hackworth, etc., supra.

11 Under Rule 13 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure it was proper (indeed, may have been compulsory) for petitioner to plead that offsetting claim as a counterclaim.

1 The complaint alleges two causes of action, of which only the first is involved in this proceeding. The second was decided adversely to respondent by the District Court and was abandoned on appeal.

2 The position of the Executive Branch and of the petitioner as well is based on the assumption that the counterclaim is a valid claim, supported by the record and that the only issue is the sufficiency of the respondent’s defense thereto. But this is not so; there is no record to support a judgment on the counterclaim in any event. See Points V and VI, infra, pp. 32-38. Logically that should therefore be the first issue to be considered by this Court, since if respondent is right there is no occasion to consider any of the different issues arising out of the act of state doctrine and the alleged exceptions thereto. We have not been logical, however, in the writing of this brief because the Court of Appeals considered the issues in such sequence that it never reached the question of the validity of the counterclaim, although it did agree that respondent’s argument as to its invalidity was made “with some justification” (J.A. 54). For that reason and because this Court remanded for further consideration of the issues arising out of the application of the act of state doctrine, we have given first attention to those issues. In fact, however, none of them need be reached.

3 The original of this memorandum will be found in the files of this Court, and was reprinted in full in 1 Amer. Soc. Int’l Legal Materials, 276, 302-305 (1962).

4 One highly relevant fact does not appear in the opinions: on August 16, 1961, the day before the Bahia di Nipe sailed into United States waters, the Cuban Government had returned to the United States an Eastern Air Lines plane which had been hijacked three weeks prior (New York Times, August 17, 1961, p. 8, col. 6).

From the political point of view, the United States could hardly refuse to return the freighter and its cargo, in view of the fact that Cuba had just returned an airplane which had come into Cuban territory under comparable conditions. The incident affords an excellent illustration of public policy considerations which motivate governments in this area of activity and of the reasons the courts should refrain from involvement.

5 That brief will be referred to hereinafter as the Sabbatino Amicus Brief.

6 See, infra, footnote 8.

7 The present Legal Advisor to the State Department was then Chairman of the International Law Committee of the Bar Association. The same views were expressed by him in 1963 in 57 Amer. J. of Int. Law 97, entitled The Sabbatino Case—Three Steps Forward and Two Steps Back, a commentary on the Court of Appeals decision in the Sabbatino case. Mr. Stevenson was then a member of the Board of Editors of the American Journal of International Law. The view was again put forward before this Court in the Sabbatino case itself.

8 The same point was also made by the Executive Branch in its testimony before Congress when it was considering the Hickenlooper Amendment. See Hearings before Committee on Foreign Relations, United States Senate, 88th Cong., 2d Sess. on S. 2659, 2660, 2662 and H.R. 11380, pp. 618, 619; Hearings Before the Committee on Foreign Affairs, House of Representatives, 89th Cong., 1st Sess., on H.R. 7750, p. 1234.

9 Throughout the legislative history of the amendment in both 1964 and 1965 it is referred to, not as the Hickenlooper amendment, but as the Sabbatino Amendment. (Senate Hearings, supra; Hearings before the House Committee on Foreign Affairs on H.R. 7750, 89th Cong., 1st Sess. [1965], passim.)

10 After his appearance before the House Committee, Professor Olmstead wrote a letter to it changing his testimony (H. Hearings, p. 1306). The letter appears to have been written with this case in mind. We do not know what prompted Professor Olmstead to change position, but his letter is almost the only support that petitioner can cite in support of its interpretation of the law.

11 After the passage of the Hickenlooper amendment, the District Court offered to petitioner an opportunity to discuss the applicability of the amendment to this case, then pending before it. Counsel for petitioner submitted a memorandum to the court declining the opportunity to present its views orally, stating:

“It has been the contention of the defendant bank, from the commencement of this action, that the obligation of Cuba was due and owing and that the counterclaim expressing that obligation up to the value of the amount sought in the complaint was a complete defense to the claim of Cuba and so was pleaded to defeat that claim. The contentions made by the defendant Bank in this case long antedated the Hickenlooper Amendment. It is the belief of the defendant that the Hickenlooper Amendment did not change, purport to change, nor intend to change the obligations of Cuba to pay for American-owned property it has confiscated and it is for this reason that it is believed unnecessary to make any further statement here concerning that new U. S. enactment.”

12 So the petitioner, at page 19 of its first brief to the Court of Appeals, said:

“The distinctions [between the case at bar and Sabbatino] . . . are fundamental. In Sabbatino the validity of Cuban Law No. 851 was challenged; in the case at bar the validity of that law is not in issue. In Sabbatino, the former owners of confiscated property asserted that, notwithstanding a fully executed act of stale, they continued to be the owners of the property; in the case at bar Citibank does not deny that Cuba effectively took Citibank’s Cuban property; Citibank merely seeks some part of the compensation due it in consequence of that taking. In Sabbatino, Cuba sought no affirmative recovery from C.A.V. or Sabbatino (its claim was to the proceeds of sugar), and neither C.A.V. nor Sabbatino asserted counterclaims or offsets against Cuba; in the case at bar, Cuba seeks a money judgment against Citibank and Citibank denies that any amount is owing because of Cuba’s offsetting money obligation to Citibank.”

13 That law provides as follows:

“Article 5. The payment for the expropriated property shall be made, after the due appraisal thereof, in accordance with the following rules, to wit:

a) The payment shall be made in Bonds of the Republic, which will be issued for that purpose by the Cuban State and shall be subject to the terms and conditions set forth in this law.

b) For the amortization of said bonds, and by way of security therefor the Cuban State shall set up a sinking fund which shall be fed annually with twenty-five per cent (25 %) of the foreign exchange corresponding to the excess of the purchases of sugar made in each calendar year by the United States of North America over and above Three Million (3,000,000) Spanish Long Tons, for their domestic consumption, at a price of not less than 5.75 cents of a dollar per English pound (F.A.S.). To this end the National Bank of Cuba shall open a special dollar account which shall be captioned ‘Fund for the Payment of Expropriations of Properties and Enterprises of Nationals of the United States of North America.’ ”

Bonds have not been issued and there are no funds out of which compensation can be made under the provisions of the law.

14 In its first petition for certiorari, petitioner urged, as its fourth “Question Presented” the argument that an ex parte decision by Foreign Claims Settlement Commission was decisive in its favor. See Petition for Certiorari, pp. 3, 6. The point seems to have now been abandoned, though the fact of the Commission’s action is recited at page 3 of petitioner’s brief on the writ. In any event, respondent answered the argument in its opposition to that petition, at pp. 7 to 9 and reference is made thereto should the Court wish to consider that point.

15 A transcript of the remarks by Mr. Chayes is available from the files of the Bar Association.

16 For a detailed discussion, see the opinion prepared for the Supreme Court by Chief Justice Taney, printed at 117 U.S. 567.

17 A strong Congressional policy against retroactive operation of statutes extinguishing substantive rights is reflected in 1 U. S. C. § 109 and reflects Congressional sensitivity to this constitutional issue.

18 The statutes creating the bank and the unchallenged affidavit of Dr. Lopez Gonzales make it abundantly clear that Banco Nacional is an autonomous state instrumentality with an identity and capital of its own and that under Cuban law it is not responsible for the debts of the Republic of Cuba. Indeed, Art. 2 of Law 930 of February 23, 1961 (an English translation of which is annexed to the Lopez Gonzales affidavit as Ex. 2) specifically provides that the plaintiff “shall not answer for the obligations of the state or other government agencies and state enterprises, unless such obligations have been expressly assumed”. The law further provided (as had the 1948 law which created the plaintiff) that the plainitff had an independent juridical status (Art. 1 of Law 930), that it had a capital structure of its own (Art. 6) and that it had its own “functional autonomy” (Art. 11).

19 In a qui tarn action where the government sues on behalf of an individual (i.e. non governmental) informer, the same rules apply and a counterclaim may only be interposed against the true “opposing party”. See United States ex rel. Rodriguez v. Weekly Publications, 74 F. Supp. 763, 768-69 (S.D.N.Y. 1947) for a discussion of how this determination of the real “party” is made for Rule 13 purposes.

20 This is, of course, the exact opposite situation to that in National City Bank of New York v. Republic of China, supra, where it was the Republic which sued to collect money deposited in the defendant bank by one of its governmental agencies. Since it was the named party there, a counterclaim was permitted against it as the Republic of China, although no counterclaim would presumably have lain against its agency, the Shanghai-Nanking Railway Administration.

21 This Court has said, concerning such writings: “Such works are resorted to, not for the speculations of their author concerning what the law ought to be, but for the trustworthy evidence of what the law really is.” The Paquete Habana, 175 U.S. 677, 700.

22 For a sampling see: Books—Domke, International Aspects of European Expropriation Measures (1941); Foighel, Nationalisation; A Study in the Protection of Alien Property in International Law (1957) ; Friedman, Expropriation in International Law (1953) ; Nishoff, Confiscation in Private International Law (1956) ; Re, Foreign Confiscations in Anglo-America v. Law (1951) ; U. S. Dep’t of State, Compensation for American-Owned Lands Expropriated in Mexico (1939) ; G. White, Nationalization of Foreign Property (1961); Wortley, Expropriation in Public International Law (1959).

Articles— Abdel-Wahab, , Economic Development Agreements and Nationalization, * 30 U. Cine. L. Rev. 418 (1961)Google Scholar; Allison, , Cuba’s Seizure of American Business, 47 * A. B. A. J. 48 (1961)Google Scholar; Baade, Expropriation of Foreign Private Property and The Decline of the Act of State Doctrine, 1963 J. Bus. L. 182; Becker, Just Compensation in Expropriation Cases: Decline and Partial Recovery, 53 Am. Soc. Int’l Proc. 336 (1959); Dawson and Weston, “Prompt, Adequate and Effective”: A Universal Standard of Compensation?, 30 Fordham L. Rev. 727 (1962) ; Domke, Foreign Nationalizations: Some Aspects of Contemporary International Law, 55 Am. J. Int’l L. 585 (1961); Domke and Baade, Nationalization of Foreign-Owned Property and the Act of State Doctrine—Two Speeches, 1963 Duke L. J. 281; Drucker, Compensation Treaties Between Communist States: An Addendum, 10 Int’l and Comp. L. Q. (1961) ; Farchiri, Expropriations and International Law, 1952 Brit. Int’l L. 15; Graving, Shareholder Claims Against Cuba, 48 A. B. A. J. 226 (1962) ; Katzarov, Validity of the Act of Nationalization in International Law, 22 Modern L. Rev. 639 (1959) ; Kissam and Leach, Sovereign Expropriation of Property and Abrogation of Concession. Contracts, 28 Fordham L. Rev. 177 (1959); Kutner, Habeas Proprietatim : An International Remedy for Wrongful Seizures of Property, 38 U. Det. L. J. 419 (1961); Mann, Outlines of a History of Expropriation, 75 L. Q. Rev. 188 (1959); Metger, Act of State Doctrine and Foreign Relations, 23 U. Pitt. L. Rev. 881 (1962); Patty, Tax Aspects of Cuban Expropriations, 16 Tax L. Rev. 415 (1961) ; Re, Foreign Claims Settlement Commission: Its Functions and Jurisdiction, 60 Mich. L. Rev. 1079 (1962); Reeves, Cuban Situation: The Political and Economic Relations of the U. S. and Cuba, 17 Bus. Law 980 (1962) ; Rheinstein and Wortley, Observations on Expropriation, 7 Am. J, Comp. L. 86 (1958); Seidl-Hohenveldern, Communist Theories on Confiscation and Expropriation: Critical Comments, 7 Am. J. Comp. L. 541 (1958) ; Timberg, Expropriation Measures and State Trading, 55 Am. Soc. L. Proc. 113 (1961); Todd, Winds of Change and the Law of Expropriation, 39 Can. B. Rev. 542 (1961) ; Williams, International Law and the Property of Aliens, Brit. Yb. Int’l L. 1 (1928); Wortley, Protection of Property Situated Abroad, 39 Tul. L. Rev. 739 (1961); Rafat, Compensation for Expropriated Property in Recent International Law, 14 Villanova Law Review 199 (1969).

23 That the Resolution was, in fact, an outright confiscation, pro tanto, of the property of aliens, has not escaped the attention of other countries. See the views of Mexico, in its note of Sept. 1, 1938 [1938] 5 For. Rel. U. S. 698.

24 The only two cases we have ever seen which attempted this task were Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. v. Jaffrate (the Rose Mary) [1953], 1 Weekly L. R. 246, and Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. Ltd. v. S.U.P.O.R. (Rome) [1955], Int’l L. Rep. 23 In the first of these cases (which was sugsequently critisized by the Court of Chancery in In re Helbort Wagg & Co. Ltd. [1956], 1 Ch. 323), an English colonial court at Aden found that the Iranian Oil Nationalization Decree of 1951 was in violation of International law because it did not provide adequate compensation to the owners of the oil wells. In the latter case, the Rome court found the opposite, namely, that the nationalization decree did provide adequate compensation. To complete the picture, the Tokyo court, in Anglo-Iranian Oil Co. V. Idemitsu Kasan Kabushike Kaisha [1953] Int’l L. Rep. 305, in considering the same nationalization decree, could find no standards of international law-to apply.

25 There is a voluminous literature on the subject of Cuban expropriations.

See, for example, Huberman & Sweezy, Anatomy of a Revolution (1960); Williams, The United States, Castro and Cuba (1962); Morray, The Second Revolution in Cuba (1962) ; Phillips, Island of Paradox (1960); Smith, The United States and Cuba (1960); Zeitlin and Scheer, Cuba: Tragedy hi Our Hemisphere (1963).

The easiest reference in English to the specific nationalization decrees can be found in the files of the New York Times which, from time to time, reported the progress of nationalization. The first important nationalizations took place with the passage of the Agrarian Reform Act of May 17, 1959. By December 8, 1960 substantially every major enterprise in Cuba, whether owned by Cubans or by aliens, was nationalized. So far as the banking industry was concerned, the first nationalization was of the Chinese (Taiwan) Bank on September 5, 1960 (New York Times, September 6, p. 18, col. 4). United States banks were nationalized on September 17, 1960 and Cuban owned banks on October 13, 1960 (New York Times, October 15, 1960, p. 1, col. 8). Canadian banks were nationalized on December 8, 1969. No compensation was paid for any of these nationalizations. It is difficult to see how any finding of discrimination can be made in these circumstances. The element of discrimination found by the Court of Appeals in Sabbatino (at p. 867) was not present in the case of the nationalization of the banks.

1 The Soviet view on nationalization is best expressed by Bystricky in Notes on Certain International Problems Relating to Socialist Nationalization, International Association of Democratic Lawyers, Proceedings of the Commission on Private International Law, 6th Congress (1956) 15. See also Doman, Post-War Nationalisation of Foreign Property in Europe, 48 Col. L. Rev. 1125, 1143-1158.

2 See Exchange of Correspondence, United States and Mexico [1938] 5 For. Rel. U. S. 679-702.

3 Dawson and Weston “Prompt, Adequate and Effective”: A Universal Standard of Compensation?, 30 Fordham L. Rev. 727, 740, 741 (1962).

4 Ibid.

5 Ibid.

6 Id. at 742.

7 Id. at 743, 744. This was the procedure followed in the cases of Hungry, Bulgaria and Czechoslovakia. See Public Law 285, 84th Cong, and Public Law 604, 85th Cong.

8 Id. at 743.

9 Id. at 744.

10 Id. at 744.

11 Id. at 744.

12 Clubb, Twentieth Century China (1964), p. 322.

13 Thomas, in 1 Proceedings of the 1959 Institute on Private Investments Abroad 437.

14 Eder, Inflation and Development in Latin Amercia: A Case History of Inflation and Stabilisation in Bolivia (1968), p. 549.

15 Thomas, supra, 437.

16 Dawson and Weston, supra, 748, 749; Rafat, Compensation for Expropriated Property in Recent International Law, 14 Villanova L. Rev. 236 (1969).

17 Dawson and Weston, supra, at 747; Wise and Ross, The Invisible Government (1964), pp. 110, 111.

18 Horowitz, The Free World Colossus (1965), p. 184.

19 Rafat, supra, 239-242.

20 Ebasco Industries, Inc. Annual Report 1968, p. 6; American Foreign and Power Co. Annual Report 1964, pp. 8-11; Electric Bond and Share Co. Annual Report 1967, p. 13.

21 New York Times, July 4, 1965, p. 4, col. 1; 63 Oil and Gas Journal 113 (December 27, 1965).

22 New York Times, July 29, 1965, p. 34, col. 7; New York Times, July 4, 1965, p. 4, col. 1.

23 Tanzer, The Political Economy of International Oil and the Underdeveloped Countries (1969), pp. 353, 354.

24 65 Oil and Gas Journal, p. 61 (January 9, 1967); New York Times, October 26, 1963, p. 45, col. 4; New York Times, November 16, 1963, p. 1, col. 1.

25 Wall Street Journal, August 11, 1965, p. 26, col. 2.

26 Wall Street Journal, December 31, 1965, p. 26, col. 5.

27 Wall Street Journal, February 15, 1967, p. 32, col. 1; Wall Street Journal, November 8, 1967, p. 2, col. 3.

28 Tanzer, supra, pp. 75, 76.

29 Wall Street Journal, February 7, 1969, p. 21, col. 3.

30 Wall Street Journal, March 25, 1969, p. 9, col. 1.

31 Wall Street Journal, June 26, 1970, p. 8, col. 3.

32 W. R. Grace Annual Report 1970, p. 56.

33 Wall Street Journal, October 31, 1969, p. 5, col. 1.

34 Wall Street Journal, September 11, 1970, p. 20, col. 3.

35 Wall Street Journal, September 14, 1970, p. 13, col. 2.

36 New York Times, December 16, 1971, p. 24, col. 3.

37 Wall Street Journal, October 20, 1969, p. 15, col. 1; Fortune, Vol. 82, No. 2, August 1970, p. 190.

38 13 Executive (Canada), Vol. 13, No. 6 (June, 1971), pp. 34, 35; Wall Street Journal, July 15, 1971, p. 5. col. 1; New York Times, June 28, 1971, p. 47, col. 3.

36 Chile: Documents Concerning the Nationalization of the Copper Companies, 10 Int. Legal Materials (November 1971), pp. 1235 through 1253; Wall Street Journal, December , 1971, p., col.

40 Root: The Expropriation Experience of American Companies: What Happened to Thirty-Eight Companies, 11 Business Horizons, p. 69 (April 1968).

41 [1962] 1 U. S. Code, Congressional & Administrative News, p. 2078, 87 Cong., 2d Session.