Colonial warfare has been a frequent and bloody feature of international politics. In the early nineteenth century, revolutions in Spanish America killed tens of thousands of civilians, with royalist armies “sweeping into towns and pillaging, raping, and murdering the occupants into submission.”Footnote 1 During the 1857 Sepoy Rebellion, British forces stormed Delhi, “sacking and looting the Mughal capital and massacring great swaths of the population.”Footnote 2 At the turn of the twentieth century, the Dutch military launched a series of offensives across the Indonesian archipelago during which the “population was punished arbitrarily, severely, and collectively.”Footnote 3 The interwar period featured uprisings across the Middle East, including one in Syria that the French suppressed by bombarding Damascus by means of artillery, tanks, and airplanes over multiple days, killing thousands and leaving “an entire quarter of the city … a smoldering ruin.”Footnote 4 Estimating the human toll from these conflicts is difficult, but according to one study, wars of colonial expansion alone resulted in the deaths of 25 to 30 million people, 95 percent of them civilians.Footnote 5

Despite the bloody character of colonial wars, most studies of wartime civilian harm focus on either interstate or civil wars. For interstate conflicts, scholars have explored the extent to which regime type, the identity of the combatants, the character of warfare, wartime objectives, and international legal obligations influence decisions to target civilians.Footnote 6 Scholars of civil wars have examined how the structure of the government and its armed forces, the ideological and organizational character of rebel groups, and the international context can shape when parties harm civilians.Footnote 7 The only study that has examined civilian harm in the context of colonial wars is that of Valentino, Huth, and Balch-Lindsay, who pool interstate, civil, and colonial wars in their analysis of mass killings after World War II.Footnote 8 Yet they do not consider the distinct mechanisms driving civilian targeting in colonial settings.

In this article, I argue that ignoring colonial warfare has impoverished our understanding of state-directed violence against civilians. Most studies of civilian harm in interstate wars have focused on strategic factors, emphasizing how a state's war aims and wartime strategy can create opportunities and incentives to target noncombatants.Footnote 9 These same studies have downplayed the role of ideational factors, finding a contested relationship between combatant identity, regime type, international legal commitments, and civilian harm. This emphasis on strategic factors makes sense, given that these wars are fought between sovereign states using organized militaries to advance their national interests.

But colonial wars differ from interstate wars in fundamental ways. They are fought against nonstate adversaries, outside a state's recognized international boundaries, with the aim of either establishing or sustaining hierarchic relations of imperial rule. I argue that this setting creates distinctive strategic, normative, and institutional incentives for colonial powers to harm civilians. Colonial militaries are often operating against adversaries who exploit their mobility and knowledge of the terrain to avoid battle, which can create incentives for colonial powers to embrace “scorched earth” tactics. Colonial powers are often confronted by adversaries who they perceive as racially inferior, which can make it easier for them to justify punitive collective punishments. The colonial state often struggles to generate the authority required to effectively govern, so it outsources responsibility for repression to intermediaries who apply force indiscriminately. The presence of settlers can further exacerbate these dynamics by hardening racial attitudes and unleashing escalating violent competitions over land and labor that can become “eliminationist,” if not genocidal, in character.

To assess these possibilities, I introduce and analyze a new data set of 193 cases of colonial warfare from 1816 to 2003. Using a variety of measures of civilian harm, I find that colonial wars are especially brutal. Three-quarters of states in colonial wars targeted civilians, compared to a third of states in interstate wars. Mass killing occurred nearly twice as frequently in colonial wars as in interstate wars. Colonial militaries would burn down villages, destroy crops, and seize livestock. Colonial security forces would conduct mass arrests, employ torture, and execute suspects based on little evidence. In short, the empirical record confirms that colonial conflicts deserve their reputation as “dirty wars.”

But some colonial wars are harder on civilians than others. The data suggest that colonial powers are more likely to target civilians when their indigenous adversaries employ guerrilla tactics, when their indigenous adversaries come from a different racial background, and when the colonial state relies on settlers or indigenous intermediaries to compensate for its frail governance capacity. When we ignore colonial wars, therefore, we underestimate the symbolic role that violence can play in certain settings, especially as a means of reinforcing racial hierarchies and protecting settler privileges. In interstate wars civilian harm is relatively rare and is adopted as a tactic of last resort, while in colonial wars it is commonplace and is embraced as a necessary tool of performative racialized retribution.

The rest of this article proceeds as follows. The first main section describes how existing studies have neglected colonial violence and offers some possible explanations for this oversight. The second section develops a theory of colonial violence, focusing on its unique strategic, ideational, and institutional features. The third section introduces the colonial war data set and sketches out some of the broad features of colonial violence over the past two centuries. The fourth section examines the correlates of civilian harm in colonial wars. The final section offers some observations about the benefits of integrating colonial violence into the study of wartime civilian targeting.

The Neglect of Colonial Violence

Colonial violence has not been a major focus of the study of conflict. To some extent this is an accident. As it refined its data sets, the Correlates of War (COW) project drew a distinction between three kinds of war: “interstate” wars, fought between recognized member states of the international system; “intrastate” or civil wars, fought between a state and nonstate actor within a state's territorial boundaries; and “extra-state” or colonial and imperial wars, fought between a state and a nonstate actor outside the state's territorial boundaries.Footnote 10 An unintended consequence of partitioning the data in this manner was the neglect of colonial violence in quantitative research. As Sarkees, Wayman, and Singer lament, “In contrast to virtually hundreds of publications related to the [COW] inter-state war data set, hardly any scholarship has examined the extra-state war data set.”Footnote 11

There have been studies of the causes of conflict that pooled data on interstate and colonial wars.Footnote 12 There have also been studies of civil war onset that include post-1945 anticolonial wars in their analyses.Footnote 13 Colonial wars also feature prominently in certain specialized data sets. Lyall and Wilson's data set on counterinsurgency wars contains numerous colonial cases,Footnote 14 although they do not center this in their analysis of declining trends in incumbent performance.Footnote 15 Arreguín-Toft includes a number of colonial wars in his data set on “asymmetric conflict,” but he intermixes these cases with asymmetric interstate and civil wars.Footnote 16 In short, there have been relatively few quantitative studies that have examined colonial violence on its own terms,Footnote 17 and none that has explored how the violence states unleash in colonial wars might differ in intensity or kind from violence in other conflicts.

The neglect of colonial violence is not just an issue for quantitative research. Most qualitative studies of war focus on interstate wars, especially those involving European great powers.Footnote 18 Those that focus on the “periphery” of the system tend to emphasize interstate rivalries and territorial scrambles, rather than colonial violence.Footnote 19 Perhaps most surprisingly, even studies of overseas empires can sometimes downplay the extent of colonial violence. In his history of the British Empire, Ferguson neglects to mention the violence that accompanied the suppression of postwar revolts in Kenya and Malaya, in which upwards of 30,000 civilians were killed.Footnote 20 In his survey of American involvement in “small wars,” Boot claims that the American occupation of the Philippines was “less brutal than some critics have charged,”Footnote 21 yet he omits discussion of the massacre at Bud Dajo, in which six hundred Moros, including women and children, were slaughtered.Footnote 22

There are many reasons why even these dramatic examples of colonial violence are minimized. One is that the colonial powers went to great lengths to hide their brutality. In the interwar period, British military writers articulated a doctrine of imperial policing centered on “minimum force,” an idea that supposedly reflected British common law traditions and norms of “gentlemanly restraint.”Footnote 23 Yet in practice, “coercion through exemplary force” remained “the mainstay of British counterinsurgency policy” through decolonization.Footnote 24 A related reason is that colonial officials would employ euphemisms to describe colonial violence. Massacres were redescribed as “battles.” Prisoners were not summarily executed but “shot while trying to escape.” These rhetorical deflections were not accidental but designed for metropolitan audiences, who would get “upset a little too quickly,” in the words of one French official, when confronted by reports of colonial brutalities.Footnote 25

A final reason colonial violence is ignored is that the testimonies of colonized peoples, who experienced the violence firsthand, are rarely collected or considered. The sources that we do have speak to the traumatic character of colonial wars. A pictographic account of the 1876 Battle of Greasy Grass (Little Bighorn), drawn by the Minneconjou warrior Red Horse, shows “the battle's claustrophobic messiness and carnage.”Footnote 26 An oral history provided by a witness to the 1906 Dutch assault on the Balinese kingdom of Badung, which ended in the slaughter of over a thousand civilians, recounts how “modern weaponry met weapons of yore … blood spurted and bodies piled higher.”Footnote 27 A 1914 poem by an anonymous Amazigh performer describes a French raid in the Atlas Mountains, in which “The French use fire / It burns the land / Fire stirs the wind from the west / It kills everything that it touches.”Footnote 28

Whatever the reasons, the neglect of colonial violence is unjustifiable given the importance of colonial empires. At their height prior to the Second World War, colonial empires “spread over 42 percent of the planet's area and affected 32 percent of its inhabitants.”Footnote 29 Violence played a central role in the establishment, maintenance, and ultimate collapse of these empires. Moreover, the experience of colonial violence left important legacies, shaping patterns of postcolonial state-building and the prospects of postcolonial violence.Footnote 30 Finally, the neglect of colonial violence is a missed opportunity to enrich our theories of political violence, given diversity in the modes of colonial rule and patterns of resistance across different empires.Footnote 31

A Theory of Colonial Violence

Colonial wars are staggeringly diverse and share features with both interstate and civil wars. Some colonial wars, such as the 1826 Russo–Persian War or the 1839 Anglo–Chinese Opium War, were fought along conventional lines between organized armies, and thus resemble interstate conflicts. Others, such as the 1936 Arab Revolt and the 1954 Algerian War, featured small groups of rebels utilizing guerrilla tactics, and thus anticipate many contemporary civil conflicts. Between these extremes we have numerous examples of indigenous polities opposing colonial empires, with various kinds of military forces using a wide range of tactics.

Given this variety, we must be careful in generalizing about colonial violence. Yet for all their differences, colonial wars do share some characteristics. In particular, colonial wars are (1) fought by states outside their own territorial boundaries, (2) against adversaries who are not recognized members of the international system, (3) with the goal of establishing or sustaining hierarchical relations of dominance. I argue that these features create strategic, normative, and institutional tendencies that influence how colonial wars are fought, and I suggest specific hypotheses about when colonial powers are more likely to target civilians.

Strategic Character of Colonial Wars

One feature of colonial wars is that they are often fought by irregular forces using guerrilla methods. As Walter argues, many indigenous adversaries of empire “avoided engaging in battle wherever possible” and “instead relied upon concealment, ambushes and surprise attacks, on ruses such as feigned retreats, and on surrounding and ‘cutting off’ the enemy.”Footnote 32 Indigenous polities might opt not to fight using conventional methods for a variety of reasons. In some cases they embrace guerrilla methods for tactical reasons, seeking to exploit their greater mobility, knowledge of the terrain, and intelligence advantages.Footnote 33 In other cases they use such methods because they are well suited to indigenous military manpower systems, which are centered on small bands of fighters operating independently.Footnote 34 Indigenous polities may also avoid open battle in response to technological factors, withdrawing to fortifications or rough terrain to nullify colonial advantages in firepower.Footnote 35

As in other conflicts, the use of guerrilla methods by one side can generate strategic incentives for the other side to target civilians.Footnote 36 First, colonial powers may target civilians to deny guerrillas material resources, such as weapons, food, or fresh recruits. Moving civilians into fortified villages is a familiar tactic to interdict supplies intended for rebels.Footnote 37 Second, colonial powers can use civilian targeting as an intimidation tactic, to deter civilians from aiding the rebels. Burning a village suspected of aiding the guerrillas can send a message to neighboring villages.Footnote 38 Third, guerrilla tactics can take on symbolic meanings in colonial settings. Societies that embrace guerrilla modes of warfare are perceived as unchivalrous, and thus less deserving of restraint, than those who fight “honorably” in the open.Footnote 39 Whatever the motive, civilians are easier to target than elusive rebels, so civilian victimization is a cheaper counterinsurgency tactic than the systematic clearing and holding of territory.Footnote 40 All of this suggests:

H1 In colonial wars, states are more likely to target civilians when indigenous adversaries adopt guerrilla tactics.

Ideological Content of Colonial Wars

A second shared feature of colonial wars is that the indigenous adversaries of empire are not recognized members of the international system, and are often perceived as having different and inferior racial identities. The kinds of actors that have taken up arms against empires are varied, and have included military monarchies, modernizing proto-states, and “tribes” or chiefdoms, among many others.Footnote 41 What unites these actors is that colonial powers often perceive them as racial others: rather than accept them as “rational” or “civilized” states, they stigmatize them as “barbaric” or “savage” societies. Of course, the specific ways in which colonial powers understand racial differences can vary from empire to empire, and can shift over time.Footnote 42 Yet as imperial historians have emphasized, by the nineteenth century, the “color line” had become a core principle around which European empires were organized.Footnote 43

Perceptions of racial difference are not just central to the ideology of empire; they can also influence practices of colonial violence. First, they can be used to justify performative collective punishments. Because “backward” peoples purportedly act in impulsive and collective ways, colonial powers find it harder to maintain the distinction between combatants and civilians. They come to see themselves as involved in wars against entire societies, which must be chastised through collective punishments.Footnote 44 Because “barbaric” societies are governed through despotic force, colonial powers likewise assume that they will respond to only spectacular “performances of punitive violence.”Footnote 45 Second, perceptions of racial difference can be used to exempt societies from the usual normative or legal restraints related to war. “Construction of the enemy as ‘un-civilized’,” Wagner argues, “dictated and justified techniques of violence that were … considered unacceptable in conflicts between so-called ‘civilized’ nations.”Footnote 46 Because they are not recognized states, indigenous polities do not fall under the traditional ambit of international law.Footnote 47 And because nonwhite societies are perceived as “fanatical,” colonial powers believe they must adopt “emergency” legal frameworks that allow harsh measures.Footnote 48 All of this suggests:

H2 In colonial wars, states are more likely to target civilians when indigenous adversaries are perceived as having a distinct and inferior racial identity.

Institutional Context of Colonial Wars

A third feature of colonial wars is that they are fought to establish and sustain hierarchical relations of imperial rule. A key feature of imperial hierarchies, like all hierarchies, is that the dominant state (or metropole) is entitled to command, while the subordinate polity (typically a colony) is required to obey.Footnote 49 Yet imperial hierarchies are also distinctive. Metropolitan governments deprive subordinate societies of some, but not necessarily all, of their sovereignty.Footnote 50 They then appoint representatives—typically a governor, high commissioner, or some similar figure—to oversee their interests. In turn, these “men on the spot” must negotiate with indigenous intermediaries—often a king, paramount chief, or similar local authority—to share the responsibility of governing the population. The colonial state, which emerges from these various compromises, is unique. Compared to sovereign states, the colonial state has a limited governance capacity. Its territorial boundaries are often undefined, its bureaucratic infrastructure limited, and its administrative reach circumscribed. In many cases, a “thin white line” of metropolitan officials attempts to govern a large indigenous population, with colonial authority struggling to reach beyond coastal enclaves or capital cities.Footnote 51 “Even during its heyday,” Conrad and Strange conclude, “the colonial state was essentially a weak state.”Footnote 52

Given its weaknesses, the colonial state often becomes heavily dependent on intermediaries, who officials hope will augment its governance capacity and authority. Yet this reliance on intermediaries creates two potential pathways for civilian harm. First, the interests of the intermediaries and the colonial officials overlap but are not the same. Thus the situation is vulnerable to classical principal–agent problems, where intermediaries seek to exploit the authority granted them for their own parochial purposes.Footnote 53 Second, the colonial state is often unwilling or unable to exercise control over its intermediaries, in part because it fears undermining their effectiveness. This trade-off between competence and control becomes particularly acute in wartime, when the colonial state is desperate for resources to fend off armed challenges.Footnote 54 In these situations, the colonial state may let its intermediaries loose, sacrificing control for competence, in ways that allows them to abuse civilians.

While all colonial powers struggle to manage intermediaries, there are important variations between colonies. “In some contexts, colonial rule thickened into an effective apparatus of surveillance and punishment,” Burbank and Cooper observe, “but elsewhere its presence was thin, arbitrary, and episodically brutal.”Footnote 55 I distinguish between three types of colonial institutions. Settler colonies are colonial dependencies where a significant number of settlers reside on a semipermanent basis. These settlers, Robinson argues, are “ideal prefabricated collaborators.”Footnote 56 They can supplement the coercive capacity of the colonial state by volunteering for service in colonial militias. They can act as landlords or employers, integrating indigenous populations into expanding colonial economies. Yet the presence of settlers can also open up pathways of civilian harm. First, settlers tend to have different—and often more extreme—interests than colonial authorities. They tend to see colonial wars as opportunities to loot indigenous wealth, expropriate land, smash indigenous social systems, and force individuals into colonial labor markets.Footnote 57 They also tend to be more invested in the maintenance of colonial racial hierarchies and thus are more willing to sanction punitive policies that restore settler prestige.Footnote 58 Second, settlers often have competencies that colonial authorities are reluctant to sacrifice. Settler militias are seen as particularly adaptable to local modes of warfare. Settler leaders are assumed to have a strong understanding of indigenous populations. In wartime, the colonial state may feel pressure to make concessions to settler interests. All of this suggests:

H3a In colonial wars, states are more likely to target civilians when large populations of settlers are present.

Compare these dynamics to those found in indirect-rule colonies. Here the colonial state relies on indigenous “intermediaries,” “collaborators,” or “loyalists.” These actors can be used to police subject populations, administer justice, allocate land, collect taxes, and recruit corvée labor, among other tasks.Footnote 59 As with settlers, however, the reliance of the colonial state on indigenous intermediaries can put civilians at risk. First, indigenous intermediaries do not have the same interests as colonial authorities. They seek opportunities to exploit the arbitrary authority granted to them by the colonial state to monopolize resources, eliminate rivals, and appropriate the wealth and labor of their followers.Footnote 60 Colonial wars can thus provide opportunities for indigenous intermediaries to further entrench the systems of “decentralized despotism” that Mamdani argues are a core feature of indirect rule.Footnote 61 Second, indigenous intermediaries have competencies that colonial authorities prize during wartime. Indigenous fighters are valued for their knowledge of the terrain, tactical skill, and—in a racist perception—their “ruthlessness.” Indigenous elites are seen as valuable sources of local authority. In wartime, the colonial state will often increase its reliance on indigenous intermediaries, granting them license to use force indiscriminately to restore order. All of this suggests:

H3b In colonial wars, states are more likely to target civilians in indirect-rule colonies.

Compare both of these dynamics to those in direct-rule colonies, where the metropole makes extensive use of its own administrators. Instead of grafting precolonial institutions onto the colonial state, it supplants them with its own bureaucratic structures for raising revenues, administering justice, and policing populations.Footnote 62 This does not free the colonial state from some reliance on intermediaries, but it does channel collaboration into more formal settings, with indigenous actors serving as clerks, translators, and military recruits. Building direct-rule institutions can be expensive and time consuming, of course, and a colonial power's ability to do so can depend on the colony's size, revenue base, and precolonial governance institutions. Yet, as Lange argues, once they are established, direct-rule colonies tend to exhibit greater “infrastructural power.”Footnote 63 Like all colonial states, they maintain control through repression. Yet because they have a more developed coercive capacity, with more robust police forces and more extensive intelligence apparatuses, they are able to anticipate and defuse conflict more quickly.Footnote 64 Moreover, the indigenous intermediaries in direct-rule colonies tend to be different from their indirect-rule counterparts. Because they are more deeply entrenched within the colonial bureaucracy, they tend to have interests that align more closely with the colonial state, reducing principal–agent problems. Given the infrastructural power of direct-rule institutions, colonial officials are able to empower intermediaries without sacrificing control over them. All of this suggests:

H3c In colonial wars, states are less likely to target civilians in direct-rule colonies.

Patterns of Colonial Violence

To test this theory of colonial violence, I compiled a data set of 193 cases of state participation in a colonial war between 1816 and 2003. Following Sarkees, Wayman, and Singer, I define a colonial war as sustained combat between a territorial state and a nonsovereign entity outside the borders of that state that results in at least a thousand combined fatalities over the course of the conflict.Footnote 65 Within this broad category, I confine my analysis to colonial wars between European states or other great powers and nonsovereign entities outside Europe. Thus I do not consider cases of territorial conquest within Europe, such as the partition of Poland. I also do not consider cases of expansion by non-European empires, such as the Chinese subjugation of Tibet. These restrictions allow me to focus on what scholars consider the most essential and puzzling feature of modern imperialism: the dramatic expansion of European states into the “periphery” of the international system over the course of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.Footnote 66

I identified cases using a variety of sources. First, I included every case of a colonial war in the COW extra-state war data set, excluding those within Europe (such as the Garibaldi Expedition) and those that did not involve a European state or a great power protagonist (such as Egypt's suppression of Sudanese slave traders). I also excluded cases that developed as part of an ongoing interstate war (such as the German East Africa campaign) and cases that were unresolved as of 2003 (such as the US war in Afghanistan). Second, I identified cases of colonial violence in specialized data sets on asymmetric conflict and counterinsurgency warfare that are not included in the COW extra-state war data set.Footnote 67 They included cases of violence across frontiers against indigenous peoples by expanding continental states, such as the Sioux Wars in the United States. Finally, I consulted various specialized encyclopedias of both warfare and colonialism.Footnote 68 From these sources, I identified an additional eighteen cases that had not appeared in prior data sets, including the Sétif uprising in postwar Algeria. A complete list of cases can be found in Appendix 1.

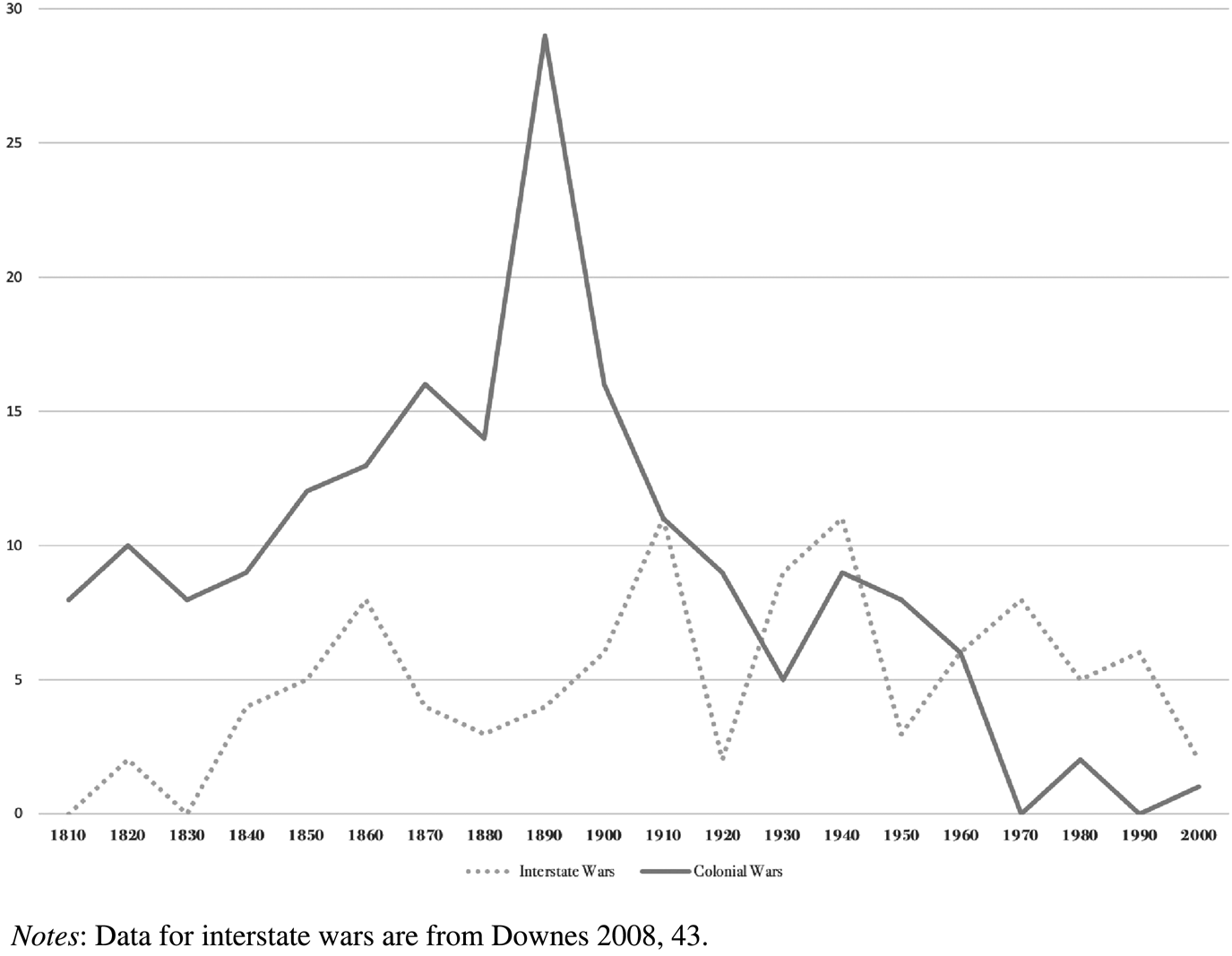

Figure 1 plots the frequency of the onset of colonial and interstate wars in each decade between 1816 and 2003. In general, colonial wars have been more common than interstate conflicts, with an average of 9.3 colonial wars starting per decade compared to 5.0 interstate wars. Outbreaks of colonial violence peaked in the late nineteenth century during the territorial scrambles associated with the “new imperialism.” They subsequently declined over the twentieth century, before nearly disappearing following the postwar wave of decolonization. A consideration of colonial violence, however, reframes how scholars periodize eras of war and peace. It is possible to talk about the nineteenth century as a period of “stability” only if we exclude colonial violence.Footnote 69 Claims of a “long peace” following the Second World War likewise require us to ignore the significant bloodshed that occurred in various wars of national liberation.Footnote 70

Figure 1. Frequency of Colonial and Interstate Wars, 1816–2003

Coding Civilian Harm in Colonial Wars

My primary outcome of interest is the intensity of state violence in colonial wars. To facilitate comparisons with existing studies, I collected data around three wartime practices. First, I examined whether colonial powers engaged in civilian victimization, which Downes defines as “a wartime strategy that targets and kills (or attempts to kill) noncombatants.”Footnote 71 Common examples of civilian victimization in colonial wars include the systematic burning of villages and the widespread destruction of crops. One challenge in coding civilian victimization is the dissonance between official policy statements and actual practice. I therefore code civilian victimization in terms of the actual battlefield practices sanctioned by leaders of colonial security forces, rather than the declarations of metropolitan officials or colonial governors.

Second, I catalog the degree of brutality employed by the colonial state across four issue areas: (1) its treatment of civilians, (2) its treatment of prisoners, (3) its use of “inhumane” weapons, and (4) its use of aerial bombardment. Following Morrow and Jo, who undertake a similar coding exercise for interstate wars,Footnote 72 I score the colonial state's methods on a four-point ordinal scale: (1) no brutality reported; (2) only minor cases of brutality; (3) major cases of brutality occur, but the state makes some attempt to minimize harm; and (4) major cases of brutality occur frequently and without constraint. For treatment of civilians, I record whether the colonial state engaged in the shelling of population centers, village burning, food control, collective punishments (such as fines and embargoes), forced resettlement, indiscriminate massacres, systematic looting, and widespread sexual violence.Footnote 73 For treatment of prisoners, I observe whether the colonial state employed mass arrests, summary executions, show trials, torture, deportation, forced labor, and the mutilation and display of dead bodies. For inhumane weapons, I note whether the colonial state used weapons that were considered inhumane by contemporaries, including chemical weapons, expanding “dum dum” bullets, and napalm and other defoliants. For aerial bombardment, I look for examples where the colonial state used fixed- or rotary-wing aircraft to target civilians, their homes, or their food supplies.

Third, I examine whether the colonial state engaged in mass killing, which Valentino defines as the intentional killing of at least 50,000 noncombatants over the course of five years or less.Footnote 74 Accurate data on civilian deaths are difficult to collect in almost all conflict environments, but matters are even more complicated in the colonial context. Colonial governments tend to exaggerate the battlefield losses of their adversaries, trumping up indecisive skirmishes into decisive victories, while downplaying the suffering of civilians. Imperial historians compensate by using demographic data to generate mortality estimates, but the quality of colonial record keeping varies, and estimates can have large margins of error. For example, Blacker concludes that “excess deaths” during the Mau Mau rebellion were probably not as high as the 300,000 figure cited in some sources, but provides a wide-ranging estimate of 30,000 to 60,000.Footnote 75 I err on the side of caution and require clear evidence of more than 50,000 deaths.

To code individual cases, I consulted a wide variety of sources. Histories of particular empires provided useful background but rarely delved into battlefield practices. Military histories proved more useful, although campaign narratives were less helpful than those that quoted extensively from soldiers’ letters and diaries. I also consulted primary documents, mostly accounts by officers involved in colonial campaigns. Every effort was made to collect narratives from colonized peoples, and when this was not possible, I endeavored to “read against the grain,” as Guha suggests, to identify potential elisions in colonial sources.Footnote 76 All told, the coding materials cite roughly 600 sources in six languages. A complete coding rubric, with examples, can be found in Appendix 2. Despite every attempt to be as thorough as possible, however, it is likely that more taboo behaviors, such as torture and sexual violence, remain underreported in the data.

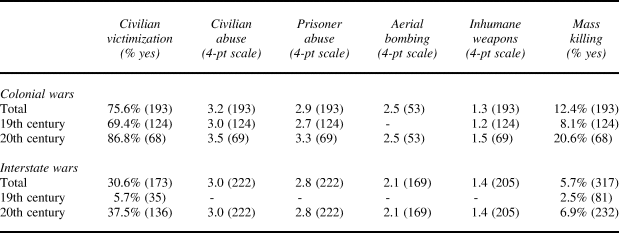

Comparing Civilian Harm in Colonial Versus Interstate Wars

I begin by comparing state-directed civilian harm in colonial wars with comparable data on interstate wars.Footnote 77 I exclude civil wars largely on the grounds of data availability; the data we have on civilian harm in civil wars either pool government and rebel violenceFootnote 78 or cover only the post–Cold War period.Footnote 79 The overall picture provided by the descriptive statistics is stark: regardless of what metric one chooses, colonial wars are particularly hard on civilians (Table 1). Whereas 31 percent of states in interstate wars engage in civilian victimization, 76 percent of state participants in colonial wars do so.Footnote 80 These findings contradict Downes, who finds (using a smaller sample of eighty-four cases of COW extra-state wars) that only 29 percent of colonial powers targeted civilians.Footnote 81 I suspect this discrepancy is driven by two factors. First, my data set is based on the updated COW extra-war data set, which provides a larger and more complete sample of cases. Second, I had the opportunity to consult more recent historical work, which has uncovered significant abuses in canonical cases, such as the 1936 Arab revolt, which had previously been viewed as models of restrained warfighting.Footnote 82

Table 1. Comparing Violence in Colonial Versus Interstate Wars, 1816–2003

Note: Numbers of cases in parentheses.

Colonial wars are also fought using more brutal methods than interstate wars. This is particularly true if we compare the behavior of colonial powers with Morrow's coding of state compliance with the laws of war. Using a four-point scale from full compliance to noncompliance, colonial powers are significantly more likely than states in interstate wars to mistreat civilians (3.5 versus 3.0), to abuse prisoners (3.3 versus 2.8), and to bomb civilians (2.5 versus 2.1).Footnote 83 The one exception to this finding concerns the use of inhumane weapons, where colonial powers and states are roughly equal in compliance (1.5 versus 1.4).Footnote 84 The most commonly reported civilian harm in colonial wars is village burning (72 percent of cases), followed by food destruction (45 percent), bombardment of towns (36 percent), and forced resettlement (31 percent). The most frequent kind of prisoner mistreatment is summary execution (55 percent of cases), followed by torture (23 percent), mass arrests (21 percent), and deportation (21 percent).

Colonial wars are also more likely than interstate wars to feature mass killings. While 6 percent of states engaged in mass killing in interstate wars, more than 12 percent of states did so in colonial wars.Footnote 85 Again, my data report a higher rate of colonial mass killings than previous studies. Valentino, Huth, and Balch-Lindsay identify two cases of mass killing in post-1945 extra-state wars (Indochina and Algeria), but my data set has eight such cases.Footnote 86 This discrepancy probably stems from my use of more recent historical work. Dutch brutality in Indonesia, for example, has been the subject of significant revisionist scholarship, which has found that “atrocities and clear cases of war crimes occurred on a regular basis and may even have been systematic.”Footnote 87 Scholars have also revisited French repression in Madagascar, which was the site of “the worst violence in a French African territory since the Rif War in Morocco twenty years earlier.”Footnote 88 The emerging picture is that the intense violence that accompanied the end of empire in well-known cases such as Algeria was far from an exception and more the rule.

Correlates of Colonial Violence

Colonial violence is worth examining not only because of its distinctive character but also because it provides a useful setting in which to test existing theories of wartime civilian targeting. As I noted in the introduction, most studies focus on the strategic incentives states have to target civilians and downplay the importance of normative factors. In what follows, I use the colonial war data set to test whether these findings hold when we examine civilian victimization in colonial settings.

Research Design

My unit of analysis is the state participant in a colonial war.Footnote 89 My dependent variable is civilian victimization, as defined by Downes.Footnote 90 Drawing on my theory of colonial violence, I consider three core explanatory variables. The first is the strategic character of the war, in particular whether an indigenous adversary employs guerrilla tactics. Coding this variable can be complicated. Ferris notes that indigenous forces in colonial wars frequently adopt “hybrid” methods, employing a mix of “regular and irregular forces” that would use their “conventional weapons in unconventional ways.”Footnote 91 Colonial wars can also change over time: the 1899 Boer War opened with a series of conventional battles and sieges, before evolving into a prolonged guerrilla conflict. I apply relatively stringent criteria for the category of a guerrilla war. Evasion and harassment must be the primary approach of an indigenous adversary throughout the conflict. I code wartime strategy as 1 if guerrilla methods predominate, and 0 otherwise.

The second explanatory variable relates to combatant identity, in particular whether colonial powers perceive their indigenous adversaries as having a different racial identity. Because race is a socially constructed concept whose meaning is constantly changing, coding this variable can be fraught.Footnote 92 Race can also take on multifaceted meanings in colonial settings. Officials in British India considered themselves superior to their colonial subjects, but also believed in a distinction between “martial” and “non-martial” races.Footnote 93 British military officers perceived their opponents in the Boer War as white, but also denigrated them as “backward” and “corrupt.”Footnote 94 To simplify matters, I follow theorists such as DuBois and focus on the overriding importance of the “color line” in colonial settings.Footnote 95 “The colonized world,” Fanon observes, “is a world divided in two,” where colonial powers draw sharp distinctions between white and nonwhite peoples and places.Footnote 96 I draw on the Ethnic Power Relations data set and its coding of a group's socially constructed racial marker, based on its origin in one of seven world regions.Footnote 97 I code combatant identity as 1 if the indigenous adversaries’ racial identity differs from the colonial power, and 0 otherwise.

The third set of explanatory variables concerns the structure of the colonial state, in particular whether a colony is a settler colony or is under indirect rule. Coding these variables is also challenging. Despite a rich literature on settler colonialism, there is no commonly accepted definition of a settler colony.Footnote 98 There are always a smattering of individuals from the metropole present in colonial settings, such as soldiers, traders, or missionaries. What makes settler colonies unique is that these people settle in large numbers, more or less permanently. The most comprehensive data on settlers come from Easterly and Levine, who code the share of European population in a given colony during its formative years.Footnote 99 I code the settler colonialism variable as 1 if the share of settlers exceeded 0.5 percent of the total population, and 0 otherwise.

Similarly, there is no consistent cross-colonial measure of indirect rule. Scholars have used various indicators—such as the proportion of court cases handled by native courts, the relative density of colonial road networks, or the survival rate of precolonial political dynasties—as proxies, yet these indicators are not available for all empires, colonies, or periods.Footnote 100 Further complicating matters is the fact that different regions within a colony can have different forms of rule. British India featured a mix of direct and indirect rule, depending on whether a territory was ruled by a native prince. At the risk of oversimplification, I consider indirect-rule colonies to be those where colonial officials are heavily dependent on indigenous institutions. For British colonies, I draw on Lange's data and consider colonies where more than half of court cases are handled by customary courts to be under indirect rule.Footnote 101 For non-British colonies, I rely on administrative histories to assess the degree of colonial dependence on local collaborators. The resulting variable is coded as 1 when a colony is governed indirectly, and 0 otherwise.

In addition to these core explanatory variables, most of my models include a battery of control variables, which I derive from the existing literature.Footnote 102 These control variables include measures of the colonial power's war aims, the colonial power's regime type, the colonial power's aggregate military capabilities, the extent to which a colonial power has ratified international legal covenants related to the laws of war, the degree of professionalism in a colonial power's military, and the duration of the colonial war. A complete description can be found in Appendix 3. In addition to these controls, some models also include fixed effects for colonial power, region, or both. Some scholars have claimed that the French style of colonial warfare, as developed by Galliéni, Lyautey, and others, favored “peaceful penetration” rather than punitive methods.Footnote 103 Colonial power fixed effects take into account the possibility that these kinds of unmodeled differences between colonial powers might account for their targeting choices. Other scholars have speculated that colonial wars fought in sub-Saharan Africa impose particular challenges on combatants due to the continent's climate, geography, and disease profile.Footnote 104 Region fixed effects take into account the possibility that these kinds of unmodeled regional differences might influence patterns of colonial warfare.

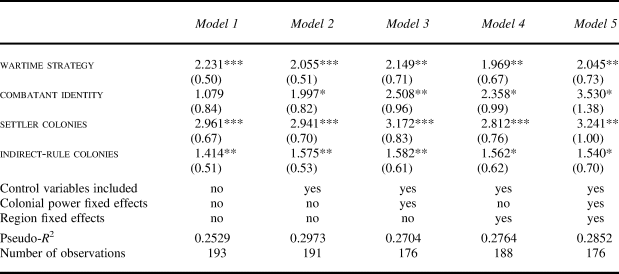

Empirical Results

Because my dependent variable is dichotomous, all models are estimated using a logit model, with robust standard errors clustered by conflict. Table 2 reports the results of five models. Model 1 includes only my core explanatory variables. Model 2 adds the control variables. Model 3 includes the controls plus colonial power fixed effects. Model 4 includes the controls plus region fixed effects. Model 5 considers the controls and both colonial power and region fixed effects. The complete regression tables for all five models can be found in Appendix 4. I discuss each of my core explanatory variables in turn.

Table 2. Correlates of Civilian Victimization in Colonial Wars

Notes: Robust standard errors in parentheses. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

Civilian Victimization in Guerrilla Colonial Wars

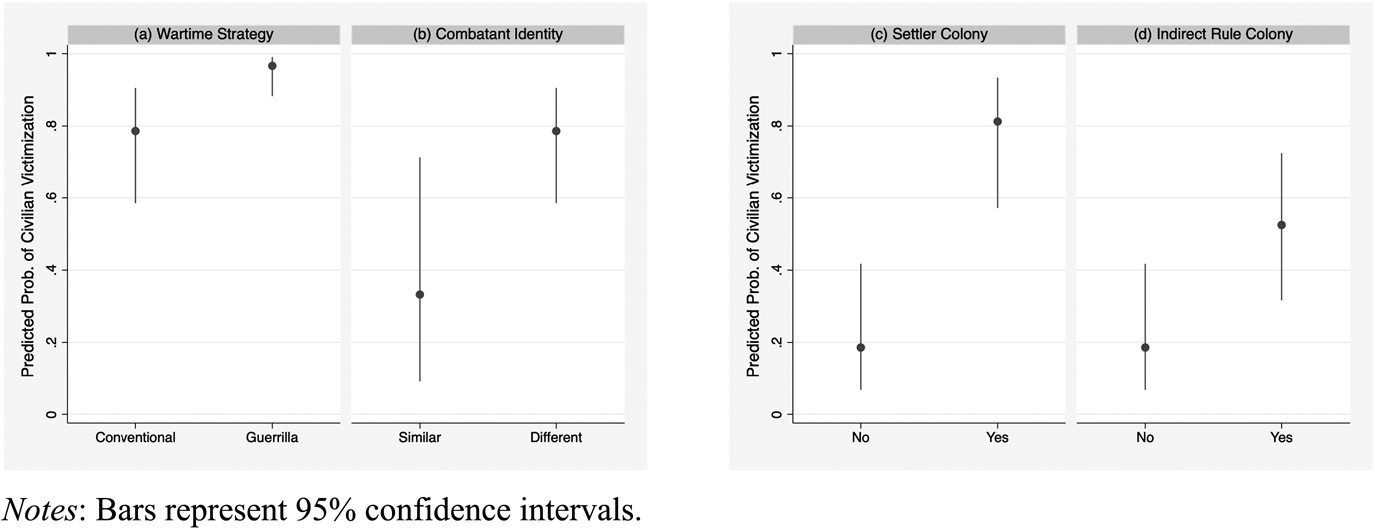

The coefficients for wartime strategy are positive and statistically significant at the p < .01 level across all five models, providing strong support for Hypothesis 1. The predicted probability that a colonial power will target civilians in a colonial war is eighteen percentage points higher when an adversary adopts guerrilla tactics (Figure 2a).Footnote 105 As in both interstate and civil wars, wartime strategy appears to be strongly associated with decisions to target civilians.Footnote 106 In this important respect, colonial wars have much in common with other kinds of conflicts.

Figure 2. Marginal Effects of Core Explanatory Variables

While the models suggest a strong association between guerrilla colonial wars and civilian victimization, the case narratives provide evidence for the particular causal mechanisms. First, colonial powers routinely targeted civilians to deny guerrillas access to resources. During the 1911 Fez Revolt, French officials decided that “to reduce such a tenacious enemy, it is necessary to burn their crops without mercy … Only then, will they come to settle.”Footnote 107 Portuguese officials reached a similar conclusion during the 1962 Guinea-Bissau War, endorsing the napalming of rural villages to “starve [insurgent] forces to death or better still force them to surrender.”Footnote 108 British authorities during the 1948 Malaya Emergency viewed the forcible resettlement of nearly 500,000 people in similar terms, stating that “if these areas are dominated to such an extent that food, money, information and propaganda were denied the enemy … the initiative then becomes ours.”Footnote 109

Second, colonial powers frequently targeted civilians to deter them from aiding guerrillas. During the 1816 Caucus Campaign, Russian commanders argued that shelling villages was “necessary as an example … to other peoples, who can be tamed only through the lessons of terror.”Footnote 110 French officials justified the bombing of suspicious hamlets during the 1930 Yen Bay uprising because “it was important to inflict on the bandits and those sheltering them a quick and exemplary lesson.”Footnote 111 Spanish authorities employed a similar logic during the 1821 Venezuelan Revolution, when they executed civilians suspected of harboring republican sympathies and displayed their cadavers “to terrorize noncombatants into either submission and loyalty or flight and exit.”Footnote 112

Third, colonial powers developed pejorative images of adversaries who adopted guerrilla tactics, as a pair of wars fought by the British East Indian Company illustrate. In 1855, the Santal tribe in Bengal fought a grueling six-month guerrilla campaign in which insurgents burnt rival villages, plundered indigo factories and railway works, and harassed colonial security forces.Footnote 113 Company officials concluded these guerrilla tactics required a harsh response. “Forbearance towards ravaging and exterminating bands perpetrating unlimited and unparalleled atrocities, is cruelty to the multitude of victims,” the Board of Control concluded, endorsing the imposition of martial law.Footnote 114 Governor General Dalhousie likewise approved harsh tactics—including the systematic destruction of Santal villages—stating simply that “these people have ceased to deserve mercy.”Footnote 115 Compare this to the Company's reaction to the 1846 Sikh War, which was largely fought along conventional lines. In this case, British sources are full of praise for the Sikhs and their martial spirit. One general wrote of the “rare species of courage possessed by these men.”Footnote 116 Dalhousie acknowledged that “the Sikhs behaved bravely, and stood their ground obstinately.”Footnote 117 Given the nature of the fighting, the Company did not engage in systematic village burning or crop destruction; instead, set-piece battles were followed by rounds of prisoner exchanges and diplomatic negotiations. Conventional war provided neither the incentive, nor justification, for brutality.

Civilian Victimization in Racialized Colonial Wars

Turning to the role of race, the coefficients for combatant identity are positive and statistically significant at the p < .05 level across four of the five models, providing mixed but positive support for Hypothesis 2. The predicted probability that a colonial power will target civilians in a colonial war is forty-six percentage points higher when their adversaries have racial identities different from their own (Figure 2b). Colonial wars are more likely than interstate wars to be fought by combatants with different racial identities (89 percent versus 57 percent) and feature higher rates of civilian victimization (76 percent versus 31 percent), which provides prima facie evidence that race matters. Yet these results suggest that there is important variation within the category of colonial wars. Colonial wars fought across racial lines are more likely to feature civilian victimization than nonracialized ones, such as when colonial powers are fighting rival white settlers. Recent work by Fazal and Greene finds that in interstate wars European states are more likely to target civilians when fighting non-European opponents.Footnote 118 These results suggest this is generally the case in colonial settings, too.

The case narratives again provide illustrations of the causal mechanisms connecting racial difference to civilian targeting. First, colonial powers frequently drew on race to legitimate collective punishments. In the 1876 Lakota War, American officers justified the shelling of Lakota villages by claiming that “Indians are the most clannish people in existence.”Footnote 119 British officials along the Northwest Frontier of India defended the razing of entire villages by observing that the Pashtun “does not possess … innocent subjects to be spared … All of them to a man [are] concerned in hostilities.”Footnote 120 French officials endorsed harsh methods during the 1894 campaign against Samory Touré based on a similarly racist view that “all the blacks understand is fear.”Footnote 121

Second, colonial powers repeatedly appealed to race to explain that normative restraints on war did not apply in colonial conflicts. German commanders responsible for 1903 genocide of the Herero and Nama were blunt in their assessment that “against ‘nonhumans’, one cannot conduct war ‘humanely’.”Footnote 122 Dutch hardliners responsible for the pacification of Aceh in the 1890s insisted that international law applied to only “European situations” and not to a conflict with “an uncivilized nation.”Footnote 123 Despite its doctrine of “minimal necessary force,” the British army claimed that the “degree of force necessary … will obviously differ very greatly between the United Kingdom and places overseas,” a carve-out that was used early on during the 1952 Mau Mau rebellion to justify mass evictions and extrajudicial killings.Footnote 124

In cases where racial differences were absent, colonial powers found it harder to endorse civilian targeting. During the 1880 Transvaal Rebellion, British generals denigrated Boers as “the most ignorant … of white men,”Footnote 125 yet British forces did not target Boer civilians, and the Cabinet ultimately agreed to restore Boer independence because it feared the conflict might “excite a war of races throughout South Africa.”Footnote 126 During the 1954 Cyprus Emergency, British officials considered the option of collective punishments, but ultimately concluded—in racially coded language—that it was “inappropriate to use such a tribal method against a more developed people.”Footnote 127

A skeptic might point to the 1899 Boer War, in which the British military employed various “methods of barbarism” against Boer civilians—including concentration camps in which thousands died from disease and malnutrition—as a notable exception.Footnote 128 Yet comparing this case to similar wars against nonwhite opponents during the same period supports arguments about the centrality of race. The concentration camps were established in part for humanitarian reasons, to save homeless Boer women and children from starvation, and when liberal critics raised concerns about their horrendous conditions, officials made efforts to improve them.Footnote 129 The British Cabinet also prohibited imperial forces from using “dum dum” bullets, in part because of concerns it would contradict a Hague Conference prohibition.Footnote 130 The British military urged its soldiers to treat detainees humanely, and in one notable case, brought charges against three officers accused of murdering Boer prisoners and civilians.Footnote 131

Compare this to the 1906 Zulu Rebellion, where colonial forces did nothing to help starving African women and children but instead forced them back into the bush;Footnote 132 where colonial forces were equipped with expanding bullets and nobody raised any objections;Footnote 133 and where colonial forces made no effort to protect prisoners. Indeed, two of the rebellion's decisive “battles” were little more than massacres, in which colonial forces slaughtered every African male they encountered.Footnote 134 The point here is not to suggest the Boer War was fought in a humane manner or to minimize anti-Boer chauvinism. Yet because the war was fought between two white opponents, there was at least some belief that violence should be kept under control and at least some effort to use regular parliamentary and legal instruments to do so. No similar expectations or protections were extended to the black Africans who rebelled four years later.

Colonial Institutions and Civilian Victimization

Turning to colonial institutions, the coefficients for both settler and indirect-rule colonies are positive and statistically significant at the p < .05 level across all five models, providing consistent support for Hypothesis 3. The predicted probability of civilian victimization is sixty-one percentage points higher in settler colonies and thirty-four percentage points higher in indirect-rule colonies, relative to a direct-rule baseline (Figure 2c, 2d). Studies by Stanton and Balcells have highlighted the important role that preexisting political institutions can play in shaping decisions to target civilians in civil wars.Footnote 135 Governance institutions appear to play an analogous role in colonial wars, creating opportunities and incentives for local actors, whether settler militias or indigenous auxiliaries, to target civilians.

The case narratives confirm that settler militias were among the most frequent abusers of civilians. During the 1850 Mlanjeni War, settler militias on the Eastern Cape frontier conducted “a brutal campaign of extermination waged against men, women, and children.”Footnote 136 Settler militias unleashed a similar “war of extermination” during the 1860 Apache War, with “Indian hunters volunteering to be paid for scalps.”Footnote 137 In the 1945 Sétif Uprising, settlers formed “self-defense groups” which fanned out into Muslim towns, conducting hastily assembled tribunals. In Guelma alone, these vigilantes executed over a quarter of the town's adult males.Footnote 138

In some cases, settlers targeted civilians to advance material goals. During the Kalkadoon Wars in Queensland, armed groups of white farmers would harass Aboriginal bands, poisoning crops and kidnapping women and children, to clear grazing pasturage.Footnote 139 Settlers seized similar opportunities for gain during the 1893 Matabele War, when raiding parties stole an estimated 100,000 cattle.Footnote 140 In other cases, settlers abused civilians because of their racist views. During the 1832 Black Hawk War, settlers conducted a brutal campaign of retribution, slaughtering women and children, with one militiaman explaining that if you “kill the nits … you'll have no lice.”Footnote 141 Even as norms of racial equality gained strength during the twentieth century, many settlers continued to harbor deep prejudices. During the 1952 Mau Mau rebellion, the settler-dominated Kenya Regiment committed numerous atrocities, an unsurprising outcome given its motto: “The only good Kikuyu is a dead one.”Footnote 142

The case narratives suggest that indigenous intermediaries played a similar role in indirect-rule colonies. During the 1892 Arab War in the Congo, Belgian officials compensated for their relatively thin administrative presence by recruiting various auxiliaries, including cannibals, who would “carry out much of the ‘dirty work’ during the campaign.”Footnote 143 French officials were so reliant on local militias in their 1899 Chad campaign that the pillaging and enslavement of the residents of defeated villages by these intermediaries became an “integral part of French strategy.”Footnote 144 The British were similarly dependent on local levies to police northern Nigeria, and when the town of Satiru rebelled in 1906, British officials sat idly by as these forces massacred its residents.Footnote 145

Colonial powers were reluctant to give up the “competencies” these intermediaries were purportedly providing. During the 1900 War of the Golden Stool, British officials raised local levies called “locusts” from traditional enemies of the Ashanti, assuming that these groups would be highly motivated fighters, and stood by when they would “murder, rape, and … enslave any Asante women and children they were able to capture.”Footnote 146 During the 1898 Philippine insurgency, the American army compensated for its lack of ties to a “class of Filipinos … willing to cooperate” by encouraging its indigenous scout units to torture civilians for information.Footnote 147 The British army addressed its intelligence deficits during the 1936 Arab Revolt by forming “special night squads,” consisting of a mix of British officers and local Jewish fighters, who developed a reputation for “vindictiveness … [and] killing in cold blood.”Footnote 148

In direct-rule colonies, in contrast, colonial officials were able to exert more control over security forces and thus temper their abuses. During the 1921 Moplah Revolt, the government of India mobilized four Indian army regiments and declared martial law, but also took steps to ensure that “petty persecution of inhabitants in places occupied by troops” was “rigorously forbidden.”Footnote 149 Similarly, during the 1942 Quit India movement, colonial authorities recognized that while “maintaining internal order was of utmost importance,” there was a “need to avoid excesses in doing so.”Footnote 150 Officials in provinces such as Uttar Pradesh thus focused on expanding the strength of the civil police and armed constabulary, and called the military out of its barracks only in exceptional circumstances. The sheer scale and complexity of the Raj's coercive infrastructure limited the need to outsource barbarism to unreliable intermediaries.

Robustness Checks and Extensions

To further explore the robustness of these findings, I conducted a series of sensitivity analyses, which are reported in full in Appendix 5. I consider various ways of operationalizing key variables, yet substituting alternative measures for wartime strategy, military professionalism, democracy, and international legal obligations do not alter the main results. I explore whether the results are biased by the fact that Great Britain is the incumbent state in almost 40 percent of colonial wars, yet the results are unchanged when I include a dummy variable for Britain's imperial wars. I assess whether the inclusion of wars involving expanding continental empires, such as the United States and Russia, might be biasing the results; yet the results hold if I confine the analysis to overseas colonies. I examine whether the distance between the metropole's capital and the location of a colonial war is associated with civilian harm. Yet neither the coefficient for distance, nor interaction terms that include it, achieve statistical significance. I also consider alternative model specifications, including models that consider individual explanatory variables on their own or that include different configurations of controls. In general, the coefficients for the core explanatory variables remain significant, with the sole exception of the combatant identity variable, which is sensitive to the inclusion of both the war aims and settler colony variables.

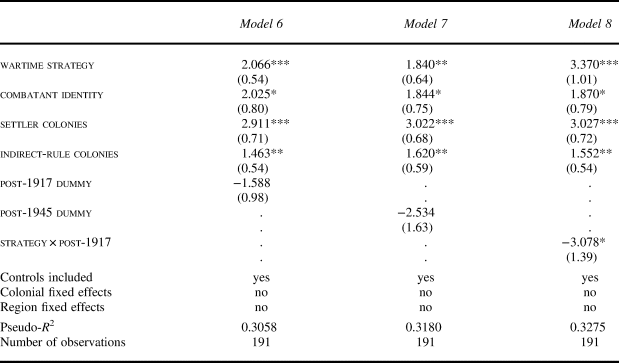

It is also possible that the findings might be driven by unmodeled temporal factors. Numerous scholars have noted the profound shifts in the strategic, economic, and normative context in which empire building took place from the nineteenth to twentieth centuries.Footnote 151 To explore this possibility, I add dichotomous variables for the post-1917 and the post-1945 periods, each of which has been posited as a turning point for practices of colonialism. Table 3 reports the results of these robustness checks. The coefficients for the post-1917 dummy variable (model 6) and the post-1945 dummy variable (model 7) do not achieve statistical significance, while the coefficients for the core explanatory variables remain unchanged. Collectively, these results suggest a surprising degree of continuity in the correlates of civilian victimization in colonial wars over time.

Table 3. Temporal Factors and Civilian Victimization in Colonial Wars

Notes: Robust standard errors in parentheses. *p < .05; **p < .01; ***p < .001.

While the correlates of civilian victimization in colonial wars appear consistent, it is possible that the strength of these associations has shifted over time. To explore this possibility, I sequentially add interaction terms for the post-1917 dummy and each of my core explanatory variables. While neither the combatant identity nor colonial institution interaction terms achieves statistical significance, the one for wartime strategy does (model 8). The predicted probability of civilian victimization is twelve points higher for guerrilla wars in the nineteenth century, but only five points higher in the twentieth century. There are two possible explanations for this decline. First, guerrilla tactics were the predominant way colonial wars were fought in the twentieth century, accounting for 84 percent of all colonial wars after 1917, which may decrease the importance of wartime strategy relative to other covariates. Second, twentieth-century colonial militaries refined their doctrines of “imperial policing,” which may have enhanced their ability to fight guerrilla wars without targeting civilians, although the brutality of many postwar counterinsurgency campaigns suggests that guerrilla tactics continued to pose profound challenges for metropolitan militaries.

Conclusion

Colonial powers claimed to be spreading civilization, yet frequently acted in barbaric ways in their colonial wars. In this article, I have argued that this penchant for brutality stems from the distinctive features of the colonial setting. Colonial powers often struggle to bring indigenous adversaries to battle, and are thus drawn to “scorched earth” methods. They frequently perceive their indigenous adversaries as racially inferior, and thus deserving targets of collective punishments. They govern imperial hierarchies through the fragile institutions of the colonial state, which can lead to insecurity, paranoia, and a tendency to respond to challenges with performative violence. Attempts to compensate for these liabilities, by recruiting settlers or indigenous intermediaries, can exacerbate these dynamics, providing additional pathways to civilian harm.

My analysis of 193 cases of colonial war between 1816 and 2003 confirms these hypotheses. Colonial powers are more likely than states in interstate wars to target civilians, to employ brutal methods, and to engage in mass killing. Variables related to the use of guerrilla methods, perceptions of racial difference, and the structure of the colonial state are all associated with civilian victimization in colonial wars across various model specifications and sensitivity analyses. Taken together, these findings modify the conventional wisdom regarding wartime civilian harm, which portrays it as a rational choice adopted for strategic reasons. In colonial wars, the normative and institutional setting is equally important. Colonial brutality is not just a wartime strategy, it is also a byproduct of racial hierarchies and imperial modes of governance.

These findings suggest a number of avenues for future research. First, they highlight the important role racial hierarchies can play in international politics. During the colonial era, race provided colonial powers with a framework for understanding why indigenous polities rebelled and what methods were required to suppress them. The experience of colonial warfare, in turn, hardened colonial understandings around race and elevated the maintenance of racial hierarchies into a central purpose of the colonial state. These racialized frameworks did not disappear with decolonization, however. They endure in the form of colonial-era ethnographies and manuals on “small wars,” which states draw on to guide their own contemporary counterinsurgency campaigns.Footnote 152 Exploring the linkages between colonial violence, racial understandings, evolving military doctrines, and varied practices of counterinsurgency is an important avenue of future research.

Second, the findings underscore the distinctiveness of the colonial state as a political unit in international politics. One of the primary imperatives of aspiring colonial state-builders was to manage violence to make up for their lack of legitimacy. The persistence of violent reactions to colonial state-building suggests that this project was necessarily contested and incomplete. The state structures that colonial powers handed over to their postcolonial successors were profoundly shaped by anxieties about—and often the experience of—colonial violence. Studies by Verghese and Mukherjee have illustrated how colonial rule left social and institutional legacies that shape patterns of political and ethnic violence in contemporary India.Footnote 153 Future studies could examine whether the experience of colonial violence, or different levels of colonial violence, has left similar historical legacies.

Finally, the findings shed light on why third-party interveners, who are often compared to colonial powers,Footnote 154 often struggle to fight nonstate adversaries in ways that avoid harming civilians. It is telling that in the three most recent “extra-state wars” in the COW data set—the 2000 Second Intifada, the 2001 Afghan Insurgency, and the 2003 Iraq Insurgency—the states involved have all been accused of mistreating civilians to varying degrees.Footnote 155 In all three cases, nonstate actors embraced guerrilla tactics and there were stark racial and religious divides between the primary antagonists. In the case of Israel, events in the West Bank highlight how the presence of armed settlers can fuel violent clashes. The American occupation of Iraq illustrates how the reliance on ethno-sectarian militias can unleash cycles of bloodletting. Reasonable people may disagree about whether these cases should be described as colonial wars, “internationalized” civil wars, or something else altogether. The bottom line is that the partitioning of data on political violence into three somewhat arbitrary categories, two of which are studied extensively and one of which is often overlooked, has limited our ability to draw meaningful comparisons. By ignoring colonial violence, we miss an opportunity to situate recent conflicts in their proper structural contexts and risk overlooking how racial prejudices and violent intermediaries can contribute to civilian suffering.

Data Availability Statement

Replication files for this article may be found at <https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/9XV0B7>.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material for this article is available at <https://doi.org/10.1017/S002081832300019X>.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Bianca Freeman, Stacie Goddard, Robert Jervis, James McAllister, Michael MacDonald, Ngoni Munemo, Craig Murphy, Costantino Pischedda, Joseph Parent, Jack Snyder, Malik Izaak Taylor, Ari Weil, the editors, and two anonymous reviewers for their comments and discussions of the article's themes.