No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

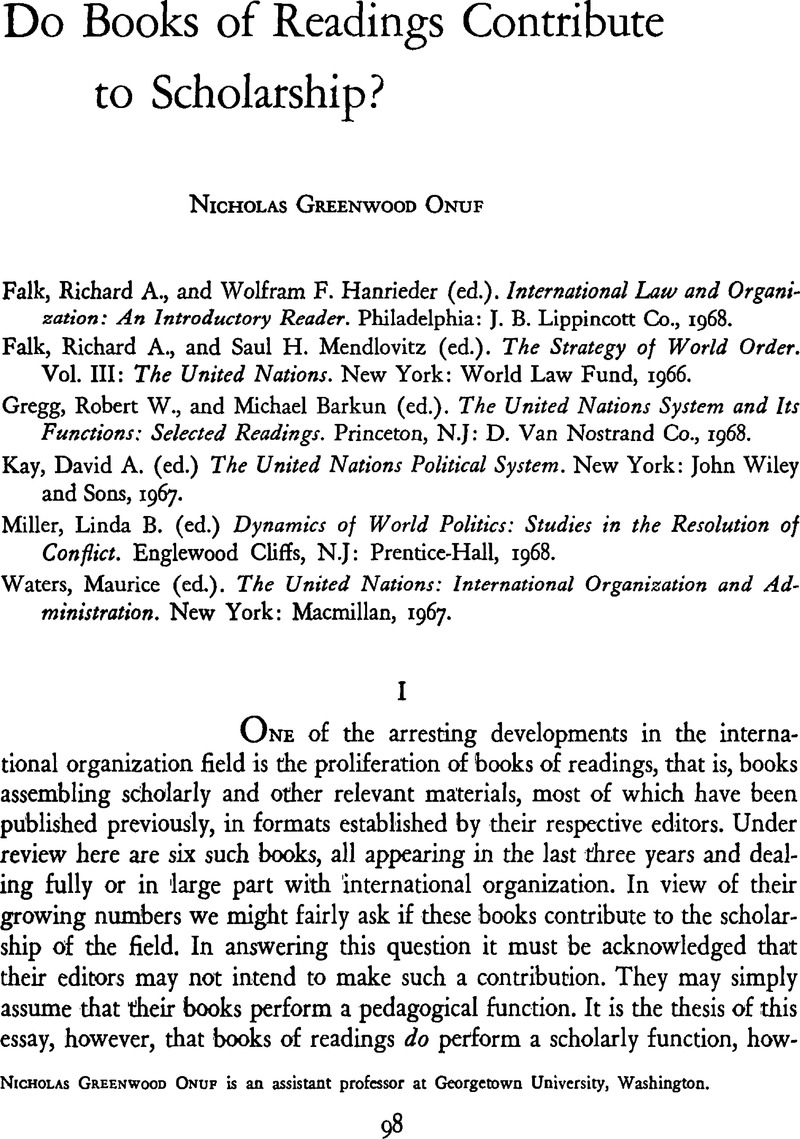

Do Books of Readings Contribute to Scholarship?

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 May 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Article

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The IO Foundation 1969

References

1 The Falk and Mendlovitz volume is the third of four parts (with two more projected) in a more general design for selecting the components of a viable strategy for the attainment of world order. While much of the editors' introductory material relates selections to the problem of developing a strategy of world order, the book itself stands alone, its design independent of the greater design.

2 While Gregg and Barkun maintain the distinction between political and governmental functions, Almond dropped it when he grafted “capabilities” onto his functional scheme. Six of the seven functions are now labeled conversion functions, and die seventh—socialization and recruitment—is called die system maintenance and adaptation function.

Almond himself is ambiguous on the precise relationship of functions and capabilities. He identifies capabilities bodi as “functions” and as “functioning” or “performance” The usual meaning of the term “capability” and Almond's commonest usage would indicate that capabilities are functions considered with the available means for dicer performance and the conditions under which they are performed. All functions must be viewed in this empirical way—as capabilities—if they are to have any analytic utility. What distinguishes Almond's capabilities from his original seven functions is not their empirical formulation but die fact that they describe the political functioning of a social system instead of die functioning of a political subsystem.

See Almond, Gabriel A. and Powell, G. Bingham Jr, Comparative Politics: A Developmental Approach (Boston: Little, Brown, 1966), pp. 27–30, 190–195Google Scholar.

3 See, for example, “Non-resolution Consequences of the United Nations and Their Effect on International Conflict,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, 06 1961 (Vol. 5, No. 2), pp. 128–145Google Scholar; and “United Nations Participation as a Learning Experience,” Public Opinion Quarterly, Fall 1963 (Vol. 27, No. 3), pp. 411–426Google Scholar.

4 Young, Oran R., The Intermediaries: Third Parties in International Crises (Princeton, N.J: Princeton University Press, 1967)CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

5 There are three variants of systems analysis relevant to social science—general systems theory, input-output analysis, and (structural-) functional analysis. The first two tend to emphasize Process and Environment in their conceptual baggage, and the third obviously tends to emphasize Structure and Function. No one variant of systems analysis gives significant or sustained attention to all four attributes although reference to all four will appear in virtually any exposition of any of the variants. See Young, Oran R., Systems of Political Science (Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall, 1968), pp. 13–48Google Scholar, for a concise treatment of the diree variants.

6 Systems are conceived, particularly in general systems theory, as being constituted by subsystems and as being subsystems themselves in larger systems. Given the relatedness of all reality implied by the concept of systems within systems, environmental phenomena must, strictly speaking, be related to a system in various larger systems but obviously not in the way a system's phenomena are related. If there were no difference, there would be no system.

Limitations of space prohibit formal definitions and further elucidation which the reader may readily supply from the systems literature.

7 This assertion views reality in terms of unending causal chains. In systems language it assumes that the output of a system (effect) is a constituent of the input to other systems (cause)—this is how systems are related.

8 By defining independent variables as explanatory factors and dependent variables as factors to be explained Oran R. Young is willing to ascribe independence to the actors, structures, processes, and context (a refinement of the idea of environment) of the international system. He views structures (not the category Structure) as independent, not in relation to processes, for example, but to five dependent variables—power, management of power, stability, change, and system transformation. Since they are “interdependent among themselves in considerable degree,” the independent variables are only really that in relation to the system's consequences (belonging to the category Function). Although he has banished it from his vocabulary, Young implicitly views Function as the attribute of the international system to be explained with the other attributes to be emphasized in providing explanations.

See Young's, A Systemic Approach to International Politics, Research Monograph No. 33 (Princeton, N.J: Center of International Studies, Princeton University, 1968), pp. 27–49Google Scholar. The quotation is from P. 35.

9 Since these attribute-categories are part of the image of reality (subjective knowledge structure) common to the members of a culture or subculture, the public for which they have a shared meaning is culturally defined. Boulding, Kenneth, The Image: Knowledge in Life and Society (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1956)CrossRefGoogle Scholar, uses the concept of image in discussing the connection between culture and knowledge.

10 See Barkun, Michael, Law without Sanction: Order in Primitive Societies and the World Community (New Haven, Conn: Yale University Press, 1968), pp. 78–81Google Scholar, for a similar discussion with appropriate references to the technical literature on perception.

11 Clark, Grenville and Sohn, Louis B., World Peace through World Law (3rd ed.; Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1966)CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

12 Dunn, Frederick S., War and the Minds of Men (New York: Harper and Bros, [for the Council on Foreign Relations], 1950)Google Scholar.

13 Haas, Ernst B., Beyond the Nation-State: Functionalism and International Organization (Stanford, Calif: Stanford University Press, 1964)Google Scholar.

14 Since isolated precursors or primitive versions can be found for most approaches, assigning dates to their appearance is somewhat arbitrary. For example, speculation on alternative systems of order for the world has been going on for centuries, but only after two world wars has it gained academic respectability.

15 Despite Stanley Hoffmann's preference for lengthy selections to avoid giving a book of readings a “shopping-center” flavor his Contemporary Theory in International Relations (Englewood Cliffs, N.J: Prentice-Hall, 1960) is still a model of how to contribute to scholarship with an approach-oriented bookGoogle ScholarPubMed.