No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

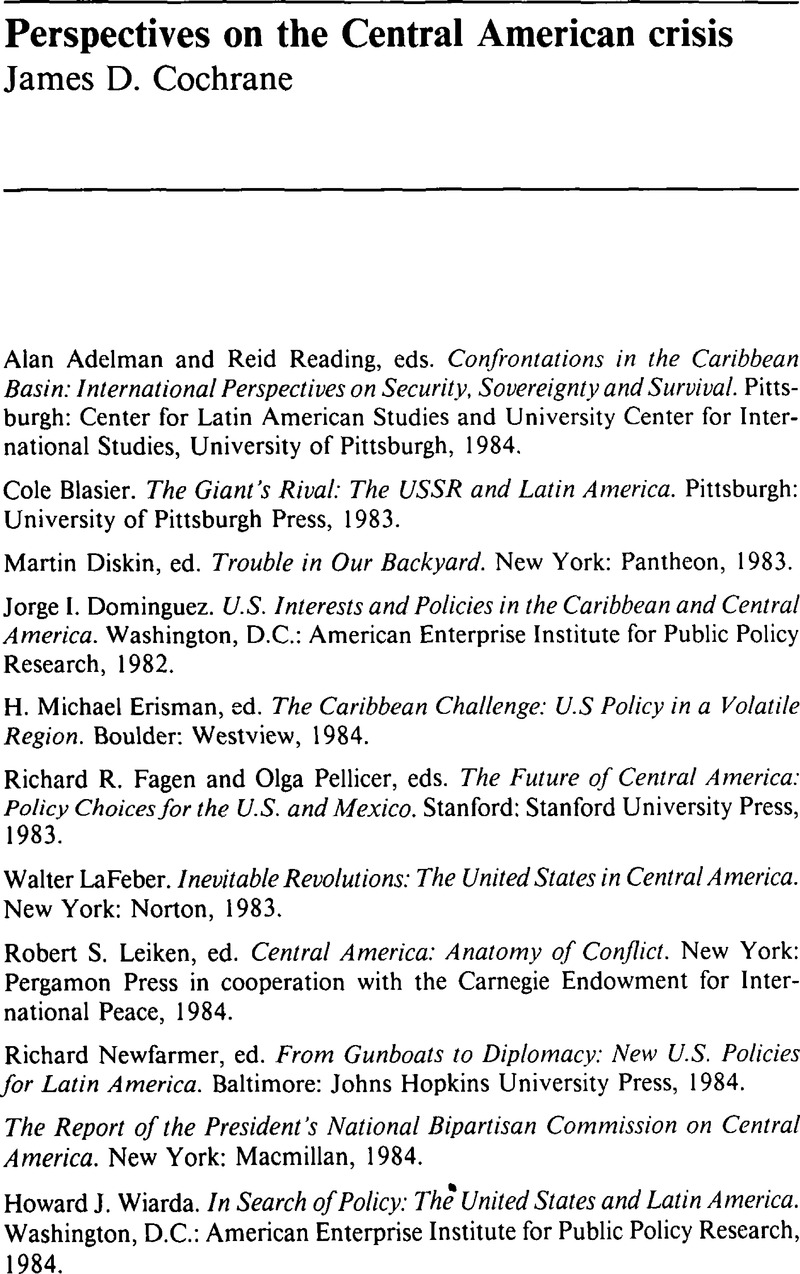

Perspectives on the Central American crisis

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 May 2009

Abstract

- Type

- Review Essay

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The IO Foundation 1985

References

1. Although some of the books under review deal with the island Caribbean as well as Central America, this essay does not address the island Caribbean situation.

2. Wiarda, , In Search of Policy, p. 135Google Scholar.

3. LaFeber, Inevitable Revolutions.

4. Ibid., p. 16.

5. Cochrane, James D., “The Evolution of U.S. Policy toward Latin America, 1945–1984: Change, Continuity, and Lessened U.S. Influence” (paper presented at the 4th Tamkang American Studies Conference, Graduate Institute of American Studies, Tamkang University, Taipei, Taiwan, 25–28 11 1984)Google Scholar, forthcoming in the published proceedings of the conference.

6. Dominguez, , U.S. Interests and Policies, p. 1Google Scholar.

7. Report of the President's National Bipartisan Commission, p. 45.

8. Dominguez, , U.S. Interests and Policies, pp. 13–17Google Scholar.

9. Wiarda, , In Search of Policy, pp. 24–25Google Scholar.

10. Hayes, Margaret Daly, “Coping with Problems That Have No Solutions: Political Change in El Salvador and Guatemala,” in Adelman and Reading, Confrontation in the Caribbean Basin, p. 38Google Scholar. Also see her book, Latin America and the U.S. National Interest: A Basis for U.S. Foreign Policy (Boulder: Westview, 1984Google Scholar).

11. For an excellent, succinct treatment of what such concepts mean in Latin America, see Dealy, Glen, “Pipe Dreams: The Pluralistic Latins,” Foreign Policy no. 57 (Winter 1984–1985), pp. 108–27CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

12. Jennie K. Lincoln, “Central America: Regional Security Issues,” and Ferris, Elizabeth G., “Mexico's Foreign Policies: A Study in Contradictions,” both in Lincoln, and Ferris, , eds., The Dynamics of Latin American Foreign Policies: Challenges for the 1980s (Boulder: Westview, 1984)Google Scholar.

13. Maira, Luis, “Reagan and Central America: Strategy through a Fractured Lens,” in Diskin, Trouble in Our Backyard, p. 37Google Scholar.

14. On the convergence of U.S.-Central American elite interests and U.S. exercise of its influence through that elite, see Wesson, Robert, “Introduction,” in Wesson, , ed., U.S. Influence in Latin America in the 1980s (New York: Praeger, 1982), pp. 1–19Google Scholar.

15. Erisman, H. Michael, “Colossus Challenged: U.S. Caribbean Policy in the 1980s,” in Erisman, and Martz, John D., eds., Colossus Challenged: The Struggle for Caribbean Influence (Boulder: Westview, 1982), p. 20Google Scholar.

16. Erisman, H. Michael, “Contemporary Challenges Confronting U.S. Caribbean Policy,” in , Erisman, The Caribbean Challenge, p. 6Google Scholar.

17. Report of the President's National Bipartisan Commission, p. 36.

18. Valenta, Jiri and Valenta, Virginia, “Soviet Strategy and Policies in the Caribbean Basin,” in , Wiarda, Rift and Revolution, p. 198Google Scholar.

19. Feinberg, Richard E., “Central America: No Easy Answers,” Foreign Affairs 59 (Summer 1981), pp. 1123–24CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

20. Schoultz, Lars, “Nicaragua: The United States Confronts a Revolution,” in Newfarmer, , From Gunboats to Diplomacy, p. 134Google Scholar.

21. LeoGrande, William M., “U.S. Policy Options in Central America,” in , Fagen and , Pellicer, Future of Central America, p. 117Google Scholar.

22. In addition to the articles by Schoultz and LeoGrande, the Nicaraguan revolution and U.S. policy toward the country are treated in several of the other works under review, including Richard Fagen, “Revolution and Crisis in Nicaragua,” in Diskin, Trouble in Our Backyard; Xabier Gorostiaga, “Dilemmas of the Nicaraguan Revolution,” in Fagen and Pellicer, Future of Central America; LaFeber, Inevitable Revolutions; Arturo Cruz Sequeira, “The Origins of Sandinista Foreign Policy,” in Leiken, Central America; and Sims, Harold D., “Revolutionary Nicaragua: Dilemmas Confronting Sandinistas and North Americans,” in , Adelman and , Reading, Confrontation in the Caribbean Basin, pp. 51–78Google Scholar.

23. Blasier, , The Giant's Rival, p. 154Google Scholar.

24. Ibid., p. 158.

25. A summary examination of the historical roots of the contemporary Central American crisis can be found in the excellent article by Woodward, Ralph Lee Jrw, “The Rise and Decline of Liberalism in Central America: Historical Perspectives on the Contemporary Crisis,” Journal of Inter-American Studies and World Affairs 26 (08 1984), pp. 291–312Google Scholar. Also, see his excellent book, Central America: A Nation Divided, 2d ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985)Google Scholar.

26. This section and the following one draw heavily on two of the works under review: Roland H. Ebel, “The Development and Decline in the Central American City State,” in Wiarda, Rift and Revolution, and Wiarda, In Search of Policy. The two sections also draw on Anderson, Charles W., Politics and Economic Change in Latin America: The Governing of Restless Nations (Princeton: Van Nostrand, 1967Google Scholar); Anderson, Thomas A., Politics in Central America (New York: Praeger, 1982Google Scholar); Ebel, Roland H., “Governing the City State: Notes on the Politics of Small Latin American Countries,” Journal of Inter-American Studies and World Affairs 19 (08 1977), pp. 325–46Google Scholar; Ebel, , “Political Instability in Central America,” Current History no. 472 (02 1982), pp. 56–59, 86Google Scholar; and Wiarda, Howard J., “The Central American Crisis: A Framework for Understanding,” AEI Foreign Policy and Defense Review 9, 2 (1982), pp. 2–7Google Scholar.

27. Anderson, Thomas P., “The Roots of Revolution in Central America,” in , Wiarda, Rift and Revolution, pp. 107–8Google Scholar.

28. Wiarda, , “The Central American Crisis,” p. 6Google Scholar.

29. Ebel, “Governing the City State.”

30. Wiarda, , “The Central American Crisis,” p. 4Google Scholar.

31. Ibid., p. 5.

32. Johnson, John J., Political Change in Latin America: The Emergence of the Middle Sector (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1958)Google Scholar.

33. Maira, Luis, “The U.S. Debate on the Central American Crisis,” in , Fagen and , Pellicer, Future of Central America, p. 88Google Scholar.

34. Milieu, Richard, “Praetorians or Patriots? The Central American Military,” in , Leiken, Central America, p. 69Google Scholar.

35. Anderson, Politics and Economic Change.

36. Wiarda, , “The Central American Crisis,” p. 5Google Scholar.

37. Hayes, , “Coping with Problems That Have No Solutions,” pp. 20–31Google Scholar.

38. Erisman, , “Contemporary Challenges Confronting U.S. Caribbean Policy,” p. 21Google Scholar.

39. Millett, Richard, “Comment” [on Hayes, “Coping with Problems That Have No Solutions”], in , Adelman and , Reading, Confrontation in the Caribbean Basin, p. 48Google Scholar.

40. Wesson, Robert, The United Slates and Brazil: The Limits of Influence (New York: Praeger, 1981Google Scholar), and Wesson, , ed., U.S. Influence in Latin America in the 1980s (New York: Praeger, 1982)Google Scholar.

41. LeoGrande, William, “Through the Looking Glass: The Kissinger Report on Central America,” World Policy 1 (Winter 1984), p. 283Google Scholar.