Article contents

Admission of European Free Trade Association states to the European Community: effects on voting power in the European Community Council of Ministers

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 22 May 2009

Abstract

Several member states of the European Free Trade Association have applied for admission into the European Community (EC). Paradoxically, enlarging the EC in this way will expand the voting power of Luxembourg, the smallest EC member state, in the EC Council of Ministers but diminish the power of the other states. In an EC with more members, voting by unanimity increasingly becomes an impractical decision-making procedure. As the Single European Act and possibly also the Treaty on European Union are being implemented, the distribution of EC council voting power takes on growing importance, since the range of issues to be decided by qualified majority votes increases considerably. Moreover, there are tendencies within the EC to render decision making more transparent and to publish member states' positions taken in majority votes. Thus, the distribution of voting power will increasingly be a crucial aspect for the EC.

- Type

- Research note

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © The IO Foundation 1993

References

This article was written while I was a visiting scholar at the Center for Political Studies at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor. I gratefully acknowledge the infrastructure provided to me while I was there, the valuable interaction with several members of the center, and especially the support by Harold K. Jacobson. Very special thanks also go to Arno C. Hoogerwerf for the construction of a computer program that calculates the Banzhaf and the Shapley-Shubik power indexes. Finally, several people have given valuable comments that have improved the manuscript. In particular—apart from three anonymous referees—I thank Chris Achen, Lars-Erik Cederman, Maria G. Fanis, Bruno S. Frey, Sieglinde Gstöhl, Ted Hopf, Kent Jennings, Jack Knight, Kar Mueller, Robert D. Pahre, Roy Pierce, and William Zimmerman.

1. For calculations based on the Banzhaf power index with respect to earlier constellations of the EC Council of Ministers, see Brams, Steven J., Rational Politics: Decisions, Games, and Strategy (Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Press, 1985)Google Scholar; and Bruno Frey, S., International Political Economics (New York: Basil Blackwell, 1984)Google Scholar.

2. This holds for the (old) consultation procedure as well as for the “cooperation procedure” introduced by the Single European Act (SEA). The new “codecision procedure” to be initiated by the Treaty on European Union grants the European Parliament veto power in selected situations.

3. However, for an analysis of the power of the European Parliament in the decision-making process, see Tsebelis, George, “The Power of the European Parliament as a Conditional Agenda Setter,” paper presented at the annual meeting of the American Political Science Association, Chicago, 3–6 09 1992Google Scholar.

4. The Comité des Représentants Permanents des Etats Membres also plays an important role by preparing decisions to be taken in the council. For an overview of the committee's functions, see Hayes-Renshaw, Fiona, Lequèsne, Christian, and Lopez, Pedro Mayor, “The Permanent Representations of the Member States to the European Communities,” Journal of Common Market Studies 18 (12 1989), pp. 119–37CrossRefGoogle Scholar. The present article will, however, concentrate exclusively on decision making within the Council of Ministers.

5. Compare, for example, Commission of the European Communities, Europe and the Challenge of Enlargement (Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 1992)Google Scholar.

6. Norway is the only nonneutral country of this group.

7. Popular opinion shows, however, that there is some skepticism involved in most of the countries with respect to EC membership. The order in which popular referenda are held could turn out to be crucial for the outcomes. If for instance Norway, in which skepticism seems to be strong, holds a referendum first, the results could have a negative influence on the numbers favoring membership in Finland and Sweden.

8. Swiss voters turned down participation in the EEA in a referendum on 6 December 1992 by a narrow margin in terms of total votes but by a clear majority of—mainly German—speaking—cantons. In contrast, the citizens of Liechtenstein decided in favor of EEA membership in a referendum that occurred shortly after the Swiss one.

9. In December 1986 the council de facto amended its procedures by allowing for majority votes on request of a member of the council or of the commission. In a report on the activities of the EC in 1988, the commission noted that “the fully accepted possibility of adopting a decision by a qualified majority forces the delegations to display flexibility throughout the debate, thus making decisionmaking easier.” See Keohane, Robert O. and Hoffmann, Stanley, The New European Community: Decisionmaking and Institutional Change (Boulder, Colo.: Westview Press, 1991), p. 7Google Scholar.

10. Article citations refer to the articles of the Treaty of Rome. See Treaties Establishing the European Communities, abridged ed. (Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities, 1987)Google Scholar. The transitory period was concluded in 1970. In accordance with article 8 of the European Economic Community (EEC) Treaty it was defined to consist of three steps comprising four years each (the treaty had become effective on 1 January 1958).

11. Article 8a states the aim of creating an area without borders and the realization of the free movement of goods, services, capital, and persons by 31 December 1992.

12. For an empirical analysis of the speed of decision making in the Council of Ministers, see Sloot, Thomas and Verschuren, Piet, “Decision-making speed in the European Community,” Journal of Common Market Studies 29 (09 1990), pp. 75–85CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

13. Banzhaf, John F. III , “Weighted Voting Doesn't Work: A Mathematical Analysis,” Rutgers Law Review 19 (Winter 1965), pp. 317–43Google Scholar.

14. For an overview of the two indexes and their computation, see Brams, Steven J., Game Theory and Politics (New York: Free Press, 1975)Google Scholar.

15. Brams, Steven J., Negotiation Games: Applying Game Theory to Bargaining and Arbitration (New York: Routledge, 1990), p. 232CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

16. With respect to the EC Council of Ministers, see Zamora, Stephen, “Voting in International Economic Organizations,” American Journal of International Law 74 (07 1980), pp. 566–608CrossRefGoogle Scholar: “the allocation of votes appears to result from a combination of population, economic power, historical precedent, and political reality” (p. 583).

17. A qualified majority basically is sufficient in all areas in which, according to the EEC treaty, decisions can be made on the basis of a commission proposal. This is the most common case. In the other cases, in addition to qualified majority voting, the support of a minimum of eight member states is necessary.

18. This drop was in accordance with a rise from four out of six to ten out of twenty-three votes.

19. See Brams, Steven J., Rational Politics: Decisions, Games, and Strategy (Washington, D.C.: Congressional Quarterly Press, 1985)Google Scholar; and Brams, Steven J. and Affuso, Paul J., “New Paradoxes of Voting Power on the EC Council of Ministers,” Electoral Studies 4 (08 1985), pp. 135–39CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

20. Brams and Affuso, “New Paradoxes of Voting Power on the EC Council of Ministers.”

21. Previously, this organization required unanimous decisions. However, since the organization parallels the EC's efforts in the framework of the “new approach” to elaborate European norms, it partially operates on the principle of qualified majority votes (the CEN/Comité Européen de Normalisation Eléctro-technique international regulations determine, moreover, that a qualified majority requires a minimum of twenty-five weighted votes in favor of a proposal, a maximum of twenty-two against it, and that the total number of member states voting against a proposal may not exceed three).

22. In the present constellation, tiny Luxembourg also holds two votes within the Council of Ministers, i.e., one-fifth of the amount of the largest members (France, Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom).

23. See Table 1.

24. Even though Germany has obtained a larger number of votes in the European Parliament since reunification, for political reasons an increase in its voting weight in the Council of Ministers seems unlikely in the near future.

25. The decline in relative power also would be large for Spain, namely from 0.109 to 0.092 in the pessimistic scenario, partial enlargement or 0.0776 in the optimistic scenario, total enlargement, if the number of votes remains unchanged at eight.

26. This increase in power is due to the fact that more coalitions are theoretically possible, and Luxembourg with two votes can more often add a crucial contribution in the new constellation.

27. If Iceland and Liechtenstein were to obtain only one vote each (while the votes accorded to the other European Free Trade Association members would correspond to the pessimistic scenario), their power would decrease to 0.012.

28. Shapley, Lloyd S. and Shubik, Martin, “A Method of Evaluating the Distribution of Power in a Committee System,” American Political Science Review 48 (09 1954), pp. 787–92Google Scholar.

29. Compare Brams, Steven J. and Affuso, Paul J., “Power and Size: A New Paradox,” Theory and Decision 7 (02/05 1976), pp. 29–56CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

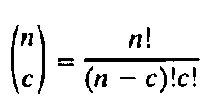

30. The equation

is the Norton Binomial denoting the number of possible coalitions consisting of c members that can be formed out of an n-member voting body.

31. Similar results—with different assumptions for an enlargement—also have been obtained by Mattei, Aurelio, “Pouvoir politique et pouvoir économique: La Suisse et l'Europe” (Political power and economic power: Switzerland and Europe)Google Scholar, cahier de recherches économiques (economic research papers) no. 9017, Department of Econometrics and Political Economy, University of Lausanne, 1990. See also Herne, Kaisa and Nurmi, Hannu, “The Distribution of A Priori Voting Power in the EC Council of Ministers and in the European Parliament,” paper presented at the European Consortium for Political Research Joint Sessions, Leiden, Netherlands, 04 1993Google Scholar.

32. Its power according to the Shapley-Shubik index presently is 0.0118.

33. From a realist perspective, it is somewhat counterintuitive that present EC states could be interested in expanding the EC and thereby assume a loss of relative power. However, the expected gain in economic advantages such as increased economies of scale may be one of the major reasons why they may indeed opt for enlargement.

34. The Shapley-Shubik index does not take account of this aspect either. For a recalculation of the Banzhaf index in the present council, on the assumption that France and Germany each have a de facto veto, see Brams, Steven J., Doherty, Ann E., and Weidner, Matthew L., “Game Theory and Multilateral Negotiations: The Single European Act and the Uruguay Round,” in Zartman, I. William, ed., The Analysis of Multilateral Negotiation (San Francisco: Jossy-Bass, forthcoming)Google Scholar.

35. See Moravcsik, Andrew, “Negotiating the Single European Act: National Interests and Conventional Statecraft in the European Community,” International Organization 45 (Winter 1991), pp. 651–88CrossRefGoogle Scholar; and Garrett, Geoffrey, “International Cooperation and Institutional Choice: The European Community's Internal Market,” International Organization 46 (Spring 1992), pp. 533–60CrossRefGoogle Scholar.

- 47

- Cited by