No CrossRef data available.

Article contents

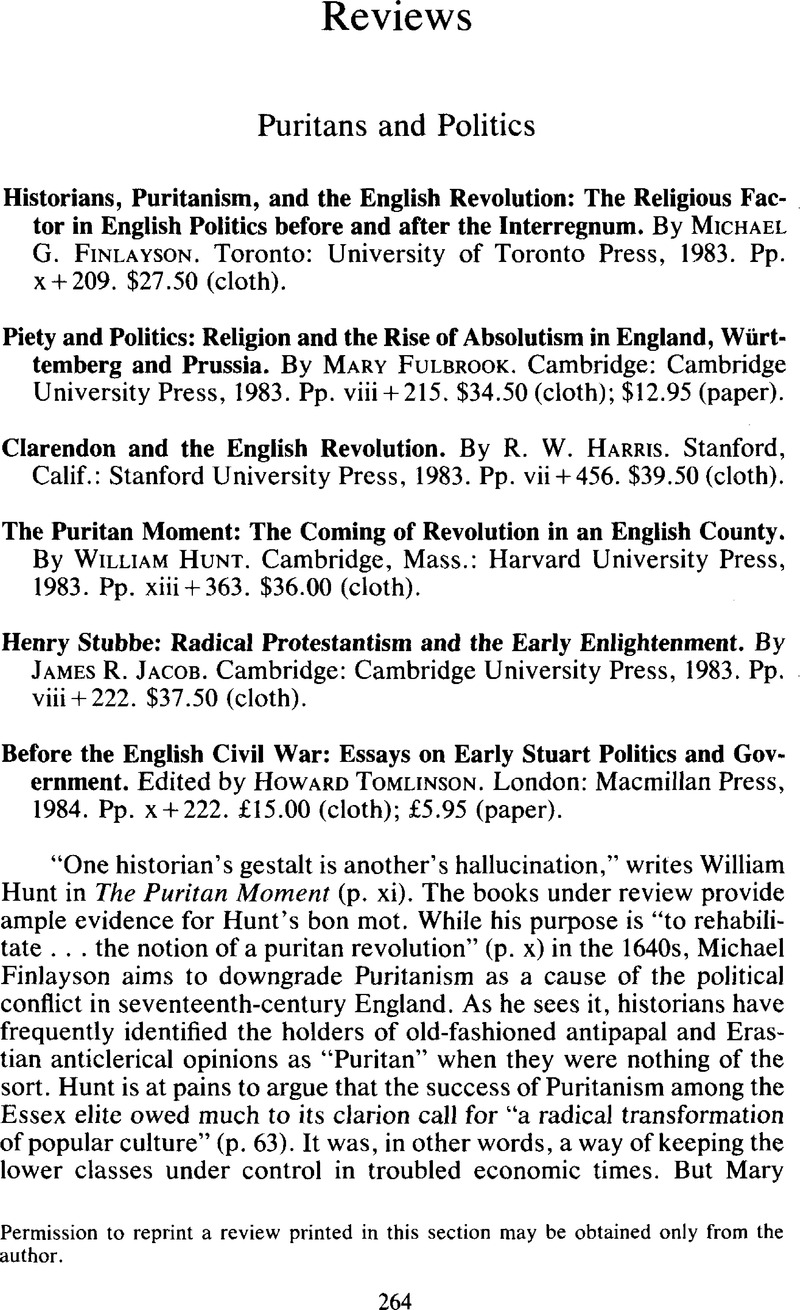

Puritans and Politics - Historians, Puritanism, and the English Revolution: The Religious Factor in English Politics before and after the Interregnum. By Michael G. Finlayson. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 1983. Pp. x + 209. $27.50 (cloth). - Piety and Politics: Religion and the Rise of Absolutism in England, Württemberg and Prussia. By Mary Fulbrook. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983. Pp. viii + 215. $34.50 (cloth); $12.95 (paper). - Clarendon and the English Revolution. By R. W. Harris. Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1983. Pp. vii + 456. $39.50 (cloth). - The Puritan Moment: The Coming of Revolution in an English County. By William Hunt. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 1983. Pp. xiii + 363. $36.00 (cloth). - Henry Stubbe: Radical Protestantism and the Early Enlightenment. By James R. Jacob. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983. Pp. viii + 222. $37.50 (cloth). - Before the English Civil War: Essays on Early Stuart Politics and Government. Edited by Howard Tomlinson. London: Macmillan Press, 1984. Pp. x + 222. £15.00 (cloth); £5.95 (paper).

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 10 January 2014

Abstract

- Type

- Reviews

- Information

- Journal of British Studies , Volume 24 , Issue 2: Politics and Religion in the Early Seventeenth Century: New Voices , April 1985 , pp. 264 - 272

- Copyright

- Copyright © North American Conference of British Studies 1985

References

Permission to reprint a review printed in this section may be obtained only from the author.

1 On the Elizabethan origins of this “Protestant polity,” see MacCaffrey, Wallace, The Shaping of the Elizabethan Regime (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1968)Google Scholar.

2 For persuasive evidence that Protestant fears about a “Catholic conspiracy” were not without some foundation, see Hibbard, Caroline, Charles I and the Popish Plot (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1983)Google Scholar.

3 See Lake, Peter, Moderate Puritans and the Elizabethan Church (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), pp. 218–42Google Scholar.

4 It also makes one more inclined to forgive the occasional overstatements and errors of fact. Sir John Hawkins was not assassinated in 1573 (p. 95)—he died in the West Indies in 1595 on an expedition with Drake. Nor are Puritan sermons characterized by “a striking absence of imagery drawn from rural or urban labor processes” (p. 124). Goodwin's, ThomasTriall of a Christians Growth (London, 1643)Google Scholar is an extended horticultural metaphor. Examples could easily be multiplied.

5 Burke, Peter, Popular Culture in Early Modern Europe (London: Temple Smith, 1978), p. 212Google Scholar. See also A. D. Wright's argument that there was from the mid-fifteenth to the mid-eighteenth century an “Augustinian moment,” during which Western Christendom was obsessed with “the most central problems of the Christian faith, salvation and grace, Justification and predestination” (The Counter-Reformation [New York: St. Martin's Press, 1982], p. 6Google Scholar).

6 On Finlayson's argument, what Fletcher calls Puritanism is nothing of the sort. As I have indicated, I think Finlayson's exorcism of the demon of Puritanism goes too far.