Introduction

On 12 May 2016, Dilma Rousseff left the presidential palace in Brasilia after the country's Senate had voted to commence impeachment procedures against her. Delivering a brief speech to supporters, she lambasted the ‘coup’ against her and Brazilian democracy, and pointed an accusatory finger at her vice-president for five years, Michel Temer.Footnote 1 Temer was indeed the first person to benefit from her fall, assuming office as president the same day.

Rousseff's accusations against her deputy, together with recent similar processes in countries such as Paraguay and Guatemala, resonate well with the history of the vice-presidency in the region. Often labelled ‘a magnet for conspiracies’,Footnote 2 or a ‘coup-maker on a state salary’,Footnote 3 the office has repeatedly been found at the centre of real or imagined coups and intrigues to oust sitting presidents.

This situation may, in turn, stem from the fact that Latin American presidents have often had vice-presidents who come from outside their own parties. As we will demonstrate, presidencies with such ‘external’ vice-presidents are almost three times as likely to suffer interruptions such as coups and impeachments than are those which have a designated successor with the same partisan background as the president.Footnote 4

There is thus reason to think that the vice-presidency matters, and, in this article, we give an account of the institution's historical evolution and current role in Latin America. More specifically, we study how vice-presidents have been elected and what role they have played during government crises. Over time, we thus observe a regional tendency towards electoral systems that should promote greater political congruence between the president and the vice-president, and, hence, decrease the likelihood of conflicts between the two. In today's Latin American democracies, however, electoral considerations have often led presidential candidates to pick running mates from outside their own political party. But by doing so presidential candidates may unwittingly be reinforcing a source of potential tension that constitution-makers in Latin America have historically tried to eliminate.

Yet our argument is not that the vice-presidency is the primary cause of such instability. Rather, we believe that the institution represents an unjustly overlooked intermediary variable and possible causal mechanism in the relationship between presidentialism, political instability and factors such as party fragmentation. Accordingly, the principal purpose of this article is to provide an empirical and analytical description of the vice-presidency in Latin America and its relationship to the presidency, thereby demonstrating its political relevance in general, and its relevance for the literature on presidentialism and governance in particular. In doing so, we are in a sense juxtaposing two positions with regard to the vice-presidency: one that presents the institution as mostly inconsequential, and one that sees it as an important factor for understanding the outcome of government crises in the presidential regimes of Latin America. But above all our approach is inductive, as we attempt to use our overview of the vice-presidency to formulate some initial propositions regarding when and how the institution may matter, and point to further lines of inquiry into the vice-presidency, its role and significance, and its relevance for studies of presidentialism in Latin America.

Previous Studies and Our Data

Vice-presidents are often dismissed as irrelevant and have rarely been the focus of systematic academic enquiry and consideration. There are exceptions to this neglect, however. For instance, Juan Linz points out the risk that the vice-presidency may bring an unqualified or unpopular politician to the presidency.Footnote 5 Similarly, Matthew Shugart and John Carey briefly discuss the possible benefits and disadvantages of having a vice-president, and the merits of different forms of electing its titular (they conclude that the best solution is no vice-presidency and a special election to fill presidential vacancies).Footnote 6 But there is to our knowledge no systematic comparative study of the office's political role either in normal political times, or in times of crisis, and one searches in vain for the inclusion of this variable in most systematic cross-national studies of different aspects of Latin American presidentialism.Footnote 7

Even so, individual vice-presidential offices in Latin America have lately received increased scholarly attention, possibly due to the prominent role some of them have played in a number of recent presidential crises. Such studies, which tend to be inspired by the US literature on the institution, fall mostly within the fields of political history and law.Footnote 8 Although they often contain considerable empirical information, there is frequently little of theoretical and comparative insight in these case studies.

The Argentine vice-presidency is perhaps the most studied vice-presidential office in Latin America, which may be because it is also the oldest such institution in continuous existence in the region.Footnote 9 The Argentine studies have focused either on the relationship between the president and the vice-president, or on the historical and institutional development of the office.Footnote 10 With the exception of the more journalistic account of Nelson Castro,Footnote 11 the role of vice-presidents during presidential crises has received less attention in Argentina.

In Bolivia, former vice-president and subsequent President Carlos Mesa directed a project on the vice-presidency, which focused mainly on the institution's history,Footnote 12 and in countries such as Colombia and Brazil one can find shorter articles about the office and its inclusion in or exclusion from various constitutions throughout history.Footnote 13 Likewise, in Mexico, even though the vice-presidency was abolished in 1917, there has lately been a constitutional and legal discussion focused on whether or not there is a need for such an institution. While some observers point to the country's troubled history with the office, others have focused on the need for clear rules for presidential succession during times of instability, and hence have argued for reinstalling the vice-presidency.Footnote 14

Although we are convinced there is more literature on the vice-presidency in the various countries in Latin America than we have been able to find and review, we believe that there is still an absence of systematic studies on the institution. Given the reputation for political meddling that the vice-presidency has traditionally enjoyed in Latin America, and the recent and historic instability of the continent's presidential regimes, we find this lacuna puzzling. The following pages are an attempt to remedy this absence by providing an overview of the institution and the role that it has filled in the politics of the continent. In doing so, we draw on data from two unique recent databases on vice-presidencies in Latin America.Footnote 15

The first database deals with the vice-presidency and the rules of succession in Latin American constitutions since independence. The data come from 188 constitutions and 68 constitutional amendments relating to the rules of succession. The second database focuses on the political relationship between presidents and their vice-presidents,Footnote 16 and on the occurrence of political crises and ‘presidential interruptions’. It covers democratic countries in Latin America in the period from 1978 to 2016 and contains information on 114 presidencies and 220 combinations of presidential and vice-presidential candidates.Footnote 17

These databases provide us with unique systematic data for Latin America in its entirety on the methods for electing vice-presidents and on the relationship between them and their presidents. Below we use this evidence to present a comparative account of the historical evolution of the vice-presidency from independence onwards, and to analyse the role of the vice-presidency during recent (1978–2016) elections and government crises in democratic Latin America.

The Origins of the Latin American Vice-Presidency

In adopting republican constitutions, the newly independent states of Latin America faced the twin problems of how to select a head of state and how to make provision for succession should that ruler become incapacitated. In the tumultuous years after independence, several mechanisms were attempted for the former task. Simón Bolívar proposed a president for life for Bolivia in 1826, and later installed a dictatorship in Gran Colombia in 1828, and Mexico attempted a monarchy under Agustín de Iturbide in 1822. With the exception of the Brazilian monarchy, all such experiences were short-lived. Inspired by French Enlightenment thinking and the example of the United States, the constitutional solution that eventually prevailed was a presidential system with direct or indirect periodic elections of the head of state.

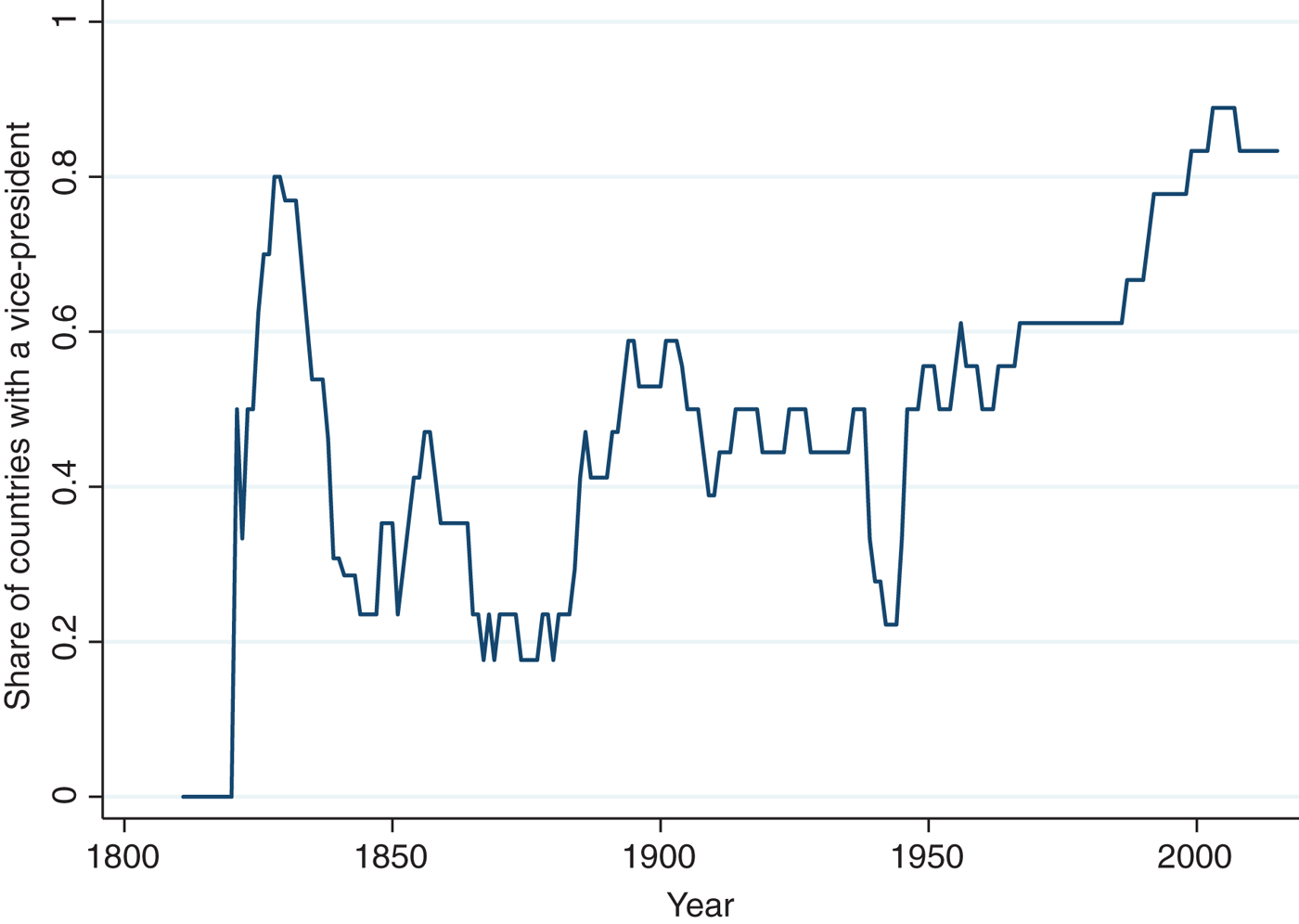

Following the US example, presidential succession in Latin America, in turn, was often entrusted to a vice-president.Footnote 18 As can be seen in Figure 1, most of the constitutions that came into force in the newly independent Latin American republics included a vice-president.Footnote 19

Figure 1. Share of Countries with One or More Vice-Presidents in Latin America since Independence

The Latin American vice-presidency, however, fell quickly in disrepute, and Figure 1 shows that the popularity of the office in the region has varied considerably over time. The anecdotes and stories concerning tensions and conflicts between presidents and their deputies are many, and it is possible that the source of the vice-presidency's reputation as a conspirator lies in the developments during this early period after independence. For instance, the first two vice-presidents of Mexico (Nicolás Bravo and Anastasio Bustamente) both tried to overthrow their presidents, though only the latter was successful (in 1830).Footnote 20 After even more conflicts involving the vice-president under the first presidency of Antonio López de Santa Anna in the early 1830s, the office was abolished for the first time in 1835.Footnote 21

The controversies surrounding the vice-presidency were not unique to Mexico. During the turbulent early nineteenth century, the role of the vice-presidency was enhanced by the long physical absences of presidents who led their armies in war.Footnote 22 Returning presidents would often find themselves in conflict with the vice-presidents who had comfortably ruled in their stead. The most famous example is probably that of Gran Colombia, where Vice-President Francisco de Paula Santander ruled during Simón Bolívar's absence in the wars of liberation. Upon Bolívar's return, their increasing political differences generated a deep rift in government, and Santander was accused of treason.Footnote 23 When Bolívar took dictatorial power in 1828, he removed the vice-presidency.Footnote 24 Similar conflicts occurred both in Bolivia in the 1830s,Footnote 25 and in Argentina during the war of War of the Triple Alliance (1864–70).Footnote 26

Accordingly, the office's reputation for being ‘a magnet for conspiracies’ (in Lloyd Meecham's term)Footnote 27 and conflicts between presidents and vice-presidents led to the abolition of the vice-presidency in six countries during the 1830s alone (see Figure 1).Footnote 28 Presidents thus often gained the upper hand in conflicts with their deputies. But while removing the vice-presidency may have terminated a source of conspiracies, it also removed an element of power-sharing, and served the interests of powerful presidents with little desire for being checked by a vice-president.

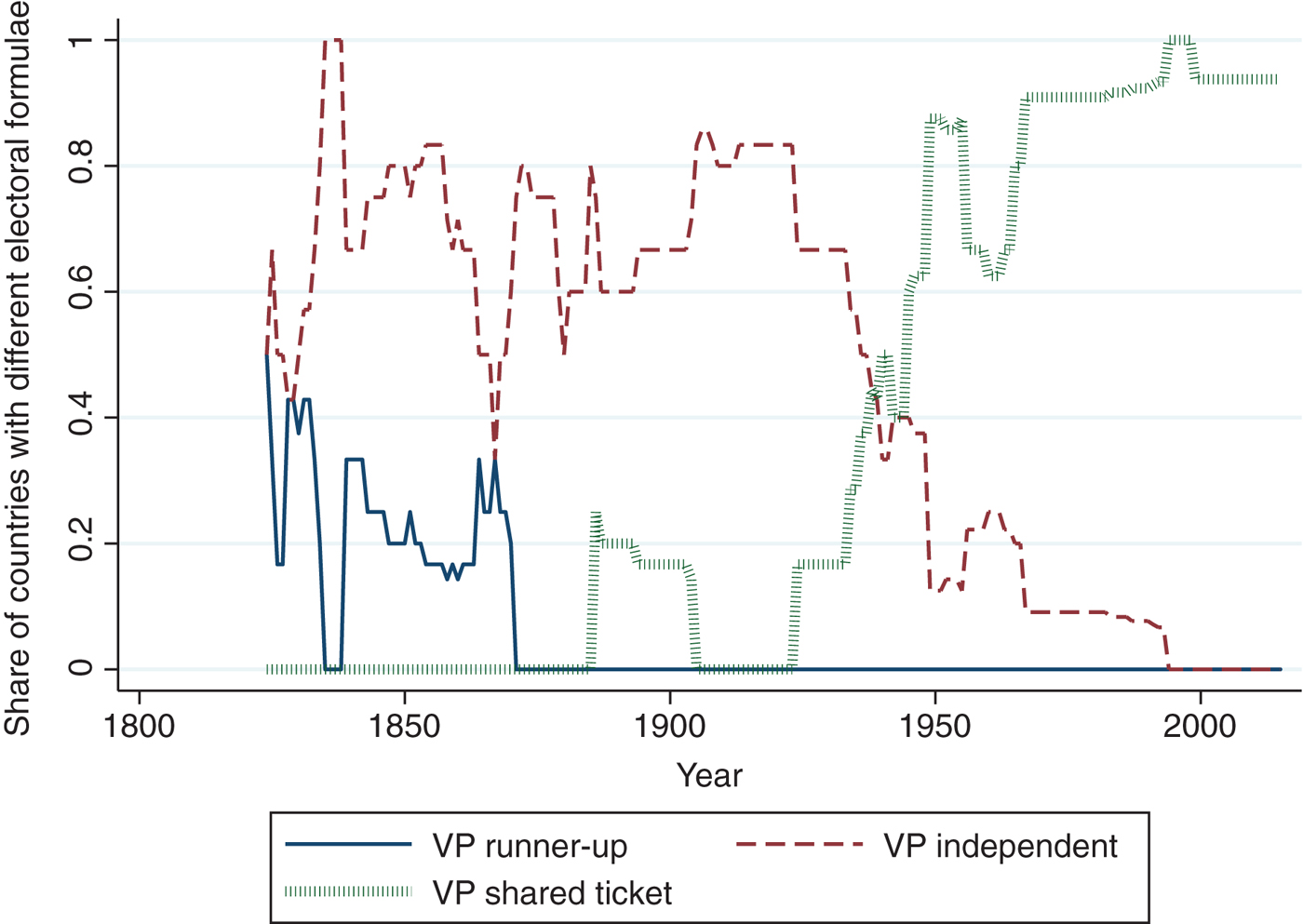

Furthermore, one could argue that it was not the vice-presidency itself that caused tension between presidents and their deputies, but rather the electoral formulae that tended to elevate antagonists to the presidency and vice-presidency. Contrary to what would subsequently become the norm, several early constitutions, such as Mexico's charter of 1824, Chile's of 1828 and Peru's of 1828, gave the vice-presidency to the runner-up in the presidential election (as did the 1787 US Constitution).Footnote 29

But this electoral formula also brought almost automatic divisions between presidents and vice-presidents, as the new president's principal competitor became his designated successor, obviously giving the latter incentives to promote the demise of the former. This point was not lost on the politicians of the early nineteenth century. In the United States the problem was solved by introducing separate ballots for presidents and vice-presidents in the electoral college in 1804. In Latin America, however, it was more common to simply abolish the institution altogether.

Nevertheless, in spite of its reputation, the vice-presidency provides a practical, economical, and stable solution to succession should the presidency become vacant, and during the decades leading up to the year 1900 vice-presidents gradually became more common again in Latin American constitutions (see Figure 1).Footnote 30 Furthermore, constitution-makers in several countries turned their attention to finding a formula for electing the vice-president that would ensure a proper balance within the executive power, but without creating the tensions recurrent in the runner-up model. As can be seen in Figure 2, which shows the different electoral formulae (the runner-up model, the independent election of the vice-president and the shared ticket model), already at the inception of the new republics a different electoral formula was being tried: separate election for vice-president. This electoral formula co-existed with the runner-up system after independence, but as the latter system was not employed after the mid-nineteenth century, independent election of the vice-president became predominant in Latin America. In 1906, independent elections of the vice-president were employed in six out of nine countries with such an office. In total, of the 125 constitutions on which we have data on the mode of election of the vice-president, 38 constitutions in 13 countries established independent elections for the office.

Figure 2. Electoral Formulae for Electing the Vice-President in Latin America

But even if the use of a separate ballot for electing the vice-president did not automatically create the same tension as the runner-up model had done, it constituted no guarantee against electing an incongruous combination of president and vice-president from different parties, and conspiracies involving the vice-president continued to be a recurring feature on the continent. Hence, apart from Vice-President Gómez’ overthrow of Cipriano Castro in Venezuela in 1908, Colombian Vice-President José Manuel Marroquín overthrew President Manuel Antonio Sanclemente in 1900,Footnote 31 Dominican Vice-President Horacio Vásquez organised a coup against President Juan Isidro Jimenes in 1902,Footnote 32 and in 1934 Vice-President José Luis Tejada was rumoured to have participated in the plot that sealed the fate of President Daniel Salamanca in Bolivia. Interestingly, Tejada and Salamanca had been elected on a joint ticket, but as representatives of different parties. Salamanca's overthrow thus contained elements that presaged future patterns.

Towards the Modern Vice-Presidency

During the first decades of the twentieth century, the proportion of Latin American republics having vice-presidents held relatively stable at one in two. What varied was the mode of election. Whereas the runner-up and separate ballot models had dominated during the century of independence, it gradually became more common to elect the vice-president on the same ballot as the president. This model had been pioneered in a couple of countries around the year 1900, and would become increasingly popular during the course of the twentieth century. This popularity may have been because it promised to end divisions between presidents and their designated successors, and is also most certainly related to the invention and establishment of parties and party systems, and the increasing prevalence of direct over indirect elections. Indeed, from the 1920s independent elections for the vice-presidency would steadily decline and, from mid-century onwards, only Brazil during its second republic (1946–64) applied this electoral formula for the vice-presidency.

In fact, developments in Brazil would provide a reminder of the perils involved in applying this system. In the 1960 election the right-wing politician Jânio Quadros was elected president, while João Goulart from the other end of the political spectrum was re-elected vice-president on a separate ballot. When Quadros suddenly resigned in the autumn of 1961, Goulart became president. The political position of the executive shifted accordingly, which – in the polarised political climate of the 1960s – set the country on the road to a military coup. Of course, neither did joint tickets guarantee political stability. In the same year as the Brazilian coup against Goulart, Víctor Paz Estenssoro of Bolivia was overthrown in a coup by his erstwhile running mate, Air Force General René Barrientos, whom he had reportedly picked as his deputy to ensure the loyalty of the armed forces. Just as in the case of Brazil, Barrientos’ act of treason spelled an end to democratic politics, and ushered in 15 years of military governments.

Given that vice-presidents in several countries thus contributed to the processes that led to the downfall of democracy, it is somewhat surprising that the period since democracy's return to Latin America in the 1980s has coincided with a renewed popularity of the vice-presidency. At the initiation of the third wave of democracy, only three out of every five Latin American countries had a vice-president. During the following years that proportion would rise to more than four out of five, as Nicaragua (1987), Venezuela (1999), Colombia (1991) and Paraguay (1992) installed vice-presidencies, and Honduras substituted such an office for the country's three ‘presidential delegates’ in 2003, only to return to the previous system in 2008–9. As can be seen in Figure 1, the vice-presidency has today attained what seems to be a region-wide and permanent presence in Latin America: the only two Latin American countries, apart from Honduras, that do not have a vice-presidency are Chile and Mexico.

With the renewed enthusiasm for the vice-presidency, the joint ticket model for electing vice-presidents has become predominant. In some countries, this may have been because of the lessons taught by history. Accordingly, the 1988 constitution in Brazil kept the vice-presidency, but stipulated that its holder should be elected on the same ticket as the president. Similar arrangements were set up in country after country, until, at the end of the twentieth century, the separate election of vice-presidents had gone the way of the runner-up model of the previous century. True, some special arrangements survived into the 2000s. For instance, Bolivia's 1967 constitution (in force until 2009) stipulated that Congress should select president and vice-president should no single ticket receive more than 50 per cent of the popular vote. In 1989, the Bolivian Congress famously picked Jaime Paz Zamora (who had come in third place in the popular vote) for the presidency, but chose Luis Ossio, the running mate of Hugo Banzer (who had come in second place) to be his deputy. More dramatically, in Paraguay in the year 2000, a by-election was held for the post of vice-president following the murder of the previous incumbent (which also led to the downfall of the president, rumoured to be behind the killing of his deputy).Footnote 33 In the event, the contest was won by the opposition candidate, leading to a situation of political tension within the government.Footnote 34

But even with the ticket-sharing model, conflicts between presidents and their designated successors have continued to be a common feature in Latin America. In Panama, for instance, a conflict about corruption allegations between President Ricardo Martinelli and his Vice-President Juan Carlos Varela, from different parties, reportedly left Martinelli's government dysfunctional.Footnote 35 In Honduras, President Manuel Zelaya and his Vice-President Elvin Santos, both from the Liberal Party, experienced serious rifts, which ended in Zelaya opposing Santos’ bid to run for the presidency in 2008. The conflict weakened Zelaya's position in his own party, contributing to his downfall in 2009.Footnote 36 Similarly, the case of Dilma Rousseff being ousted in favour of her vice-president had a precedent in neighbouring Paraguay, where an alliance of convenience – between the presidential candidate Fernando Lugo and the Liberal Party that had supplied his vice-president – turned sour in 2012 as a botched land eviction led to fatalities; the following crisis exposed Lugo to the machinations of his vice-president's party and resulted in him being voted out of office through an express impeachment that left his deputy in power.Footnote 37

The Vice-Presidency Today

As can be seen in Figure 1, the vice-presidency is today more common in Latin America than ever before, meaning that most Latin American presidents have designated successors waiting in the wings. During normal political times, however, the vice-presidency in Latin America is commonly considered unimportant and in most countries the office and its functions remain under-institutionalised. Exceptions to this rule include Argentina, Bolivia and Uruguay, where the vice-president is also the speaker of the Senate.Footnote 38 While this is often a ceremonial task, it can at times have crucial importance, as when Vice-President Julio Cobos cast the decisive vote against the Argentine government's proposed law on agricultural taxes in 2008.Footnote 39 Cobos’ actions are a reminder that the vice-presidency during normal political times may play the role of a check on the president, and contribute an element of power-sharing to the presidency. Yet, as might be suspected, such a function is likely to be resisted. Even though presidents cannot remove the vice-president, or the office, through constitutional reform, they can find other ways to neutralise the vice-president, as Cobos would learn when the president isolated him after his decisive vote.Footnote 40

Today, all vice-presidents except the Venezuelan are elected together with their presidents as part of a joint offer to the electorate.Footnote 41 Theoretically, such a joint ticket should create greater political cohesion within the executive. Yet the peculiarities and multi-party nature of Latin American politics appear to have conspired against such logic, as many presidential hopefuls seem to be doing exactly what constitution-makers in the region have tried to avoid: creating a potential political divide at the centre of executive power that can be exploited to upset the democratic process. They have done this by picking their vice-presidents from outside their own party.

The Vice-Presidency and Cross-Party Alliances in Latin America

Studies of the US vice-presidency often stress the ‘balancing’ potential of the running-mate, whereby qualities of the vice-president should complement those of the presidential candidate in order to appeal to broader electoral segments.Footnote 42 Whereas in the stable two-party system of the US such balancing relates to qualities such as age, gender and geographic origin, it is not uncommon in Latin America, in particular in the continent's more fluid multi-party systems, for presidential candidates to take a step further and balance their tickets by including persons from outside their own party.Footnote 43 Indeed, of the two leading tickets in presidential elections in Latin America between 1978 and 2016, 98 out of 220 (45 per cent) have included what can be called ‘external’ candidates for vice-president, i.e. persons who either have had a background in other political parties or who were political neophytes without any previous partisan experience (the latter group amounts to 30 candidates ranging from persons who were well known non-politicians – several of them being media personalities – to virtual unknowns whose primary quality may have been to not overshadow the presidential candidate him- or herself).

Such joint candidacies have sometimes made for very strange political bedfellows, as candidates strive to draw votes from across the political spectrum. Accordingly, the Banzer–Zamora ticket in Bolivia in 1993 comprised both a former guerrilla (Zamora) and the dictator he had sought to overthrow (Banzer). Likewise, Daniel Ortega was joined by Jaime Morales Carazo – a rightist politician and erstwhile Contra – for his electoral bid in 2006. Less dramatically, but still remarkably, Dilma Rousseff picked Michel Temer, a leading politician of the centre–right clientelistic Partido do Movimento Democrático do Brasil (Brazilian Democratic Movement Party, PMDB) for her running mate in 2010. In doing so, she was only following the precedent established by her political mentor, however.Footnote 44 For his fourth and successful run for office in 2002 Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva had chosen a running mate who would effectively allow him to dispel fears regarding the presumed radicalism of the Partido dos Trabalhadores (Workers’ Party, PT), businessman José Alencar from the rightist Partido Liberal (Liberal Party).Footnote 45

As can be seen in Table 1, such external vice-presidential candidates are much more common in countries that have a larger number of political parties. Indeed, the difference in party fragmentation between those elections in which there is at least one external vice-presidential candidate on either of the two leading tickets and those in which there is not is statistically significant at the 0.01 level.Footnote 46 While the data allow only for speculation in this regard, one may assume that it is the need to appeal to sympathisers of other parties and/or to secure future legislative majorities that explain this correlation. In Brazil since 1985, for instance, only three of the 16 leading vice-presidential candidates have come from the same party as the presidential candidate (locally known as ‘chapa puro sangue’ or ‘full-blooded ticket’).

Table 1. External Vice-Presidential Candidates on the Two Leading Tickets at Different Levels of Party Fragmentation (Latin American Elections 1978–2016)

Source: VPILA database. Sources for number of effective parliamentary parties: Manuel Alcántara, ‘Elections in Latin America 2009–2011: A Comparative Analysis’, Kellogg Institute Working Paper no. 386 (2012), App. III and Michael Gallagher, ‘Election Indices Dataset’ (2015) at http://www.tcd.ie/Political_Science/people/michael_gallagher/ElSystems/Docts/ElectionIndices.pdf (last access 12 Oct. 2018).

Note: The correlation (Pearson's r) between the number of effective parliamentary parties and external vice-presidential candidates on the two leading tickets is 0.454, and is significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed).

Even more remarkably, all of the eight vice-presidents elected in Brazil since the return of democracy have had a background in a party different from that of the president. Brazil is an extreme case, but, since 1978, out of 114 elected Latin American presidencies in systems in which a vice-president is also elected, 43 (38 per cent) have had deputies who did not have a background in the president's party (15 of these were political independents prior to their elevation to the vice-presidency, with the rest coming from other parties). Thus, in practice Latin American politicians seem to have circumvented the institutional safeguard (the joint election) against divisions and potential strife within the executive power. Interestingly, this seems to have an effect on the emergence and outcomes of government crises.

The Vice-President in Times of Crisis

While it has not been uncommon for relationships between presidents and vice-presidents to sour to the point where the latter have become vocal critics of their governments, as was the case with Julio Cobos in Argentina and Juan Carlos Varela in Panama mentioned above, this normally means little for the operation of the presidency. Indeed, the full importance of the office becomes apparent only during full-fledged political crises. This is of course in line with the institution's function, which is to provide an institutionalised structure for succession should the president become incapacitated, die or be removed. In such instances, the political relationship between vice-president and president is likely to acquire particular importance.

It can be suspected that presidents with external vice-presidents will be more likely to suffer attempts to bring about their forced removal from office. The reason for this is that interruption would in such circumstances lead to a greater political change than if the vice-president were a loyalist from the president's own party. Opposition parties seeking a political change would find the chances of producing such a change increased in the presence of an external vice-president. Indeed, several vice-presidents have actually been open about this possibility. For instance, when the Ecuadorian President Lucio Gutiérrez ran into increasing problems in 2004, and Congress was considering how to impeach him, his Vice-President Alfredo Palacio, an independent outsider, declared in the national media he was more than ready to become president should it come to that.Footnote 47

For the ‘external’ vice-president and his/her party, the prospect of a presidential interruption opens a road to the presidency, and thus an incentive to bring about such an event. The party of the vice-president would have a stronger incentive to topple the president than if theirs had been only one opposition party among others, as such an action will not only hurt a political competitor, but also give the vice-president's party supreme executive power. A slightly different logic, but no less compelling, may apply to other allies of the government. Even though they may not be next in line of succession, they may see in a less politically tainted vice-president a stronger guarantee for their interests than a beleaguered president from an unpopular party.

Accordingly, it could be assumed that external vice-presidents stand a better chance of ascending to the presidency after an interruption brought about by external agents than would an internal one. Whereas it would make little sense to interrupt a presidency only to have the president replaced with a potentially vengeful loyalist, a vice-president without direct partisan ties to the president is likely to show more gratitude towards the promoters of the interruption,Footnote 48 while bestowing a cloak of democratic legitimacy to the events that brought about the president's demise. It is likely that a president's opponent may find an external vice-president more open to such possibilities, hence increasing the risk for the president.

In fact, there is rather clear evidence as to the importance of vice-presidential partisan affiliation during crises that lead to presidential interruptions. Table 2 displays all 21 instances of permanently interrupted presidencies between 1978 and 2016 in the Latin American countries with a vice-presidency. The table identifies the main reason for the president's fall, the relationship between president and vice-president, and the eventual outcome for the vice-president. It is organised according to the reason for each president's demise, i.e. natural causes (illness, death), presidential resignations or whether an external actor forced the president's ouster through votes in Congress or a coup. As will be seen, there are certain systematic differences among these groups of cases, which indicate the importance that an external vice-president may have in times of presidential crisis.

Table 2. Interrupted Presidencies in Latin American Democracies with Vice-Presidents 1978–2016

Source: Elaborated by the authors.

Notes: a E and I denote respectively external (VP with no background in the president's party) and internal (VP with background in the president's party) vice-presidents. Vice-presidents whose names are in brackets had left office before their presidents’ fall.

b A self-coup is when a president uses unconstitutional means to dissolve or curtail the other powers of the state (legislative and judicial).

With regard to the reasons for interruption, for most of these there is no evident association between their occurrence and the presence of an external vice-president, as interruptions due to natural causes, presidential resignations or military interventions happen with equal frequency no matter what the political relationship between president and vice-president. However, when it comes to successful impeachment processes or congressional dismissals of popularly elected presidents with vice-presidencies in Latin America, it is notable that all of these have occurred in situations in which the vice-president has either come from a party different from the president's (Michel Temer in Brazil and Federico Franco in Paraguay, for instance) or has been a political independent (Alejandro Maldonado in Guatemala and Alfredo Palacios in Ecuador).Footnote 49 The evidence thus seems to support the above argument that an external vice-president may embolden a president's opponents and thus increase his or her vulnerability to forced interruptions.Footnote 50 Even though a simple association does not suffice to affirm causality in this regard, the connection is strong enough to indicate that the vice-president's political affiliation should be a factor to consider in future studies of presidential interruptions.Footnote 51

The rightmost column (‘Political Outcome’) of Table 2 indicates other interesting relationships between the vice-president's political affiliation and his or her chances of remaining in office after a presidential interruption. Cases in which death or illness was the cause of presidential disruption have always led to the assumption of the vice-president, irrespective of his or her partisan affiliation. This would be in line with expectations, as such events do not depend on political actors and their possible calculations. Yet, in the cases in which succession is triggered by political crisis, the pattern is different, and outcomes seem related both to the way in which the president leaves office, and to the political relationship between president and vice-president. In the eight cases in which presidents resigned on their own initiative in midst of crises, this has normally forced out their vice-presidents from political power as well (if they had not already left office before the president did, as in Argentina in 2001 and – a result of assassination – in Paraguay in 1999). This outcome is not surprising if the vice-president is perceived to have been jointly responsible for the situation causing the crisis. Accordingly, in no case has a presidential resignation led to a vice-president from the president's own party assuming power. The only case in which a vice-president has taken power after such an event was one in which the designated presidential successor was a political independent: Carlos Mesa, who assumed the Bolivian presidency upon Gonzalo Sánchez de Lozada's resignation in 2003. Significantly, Mesa had distanced himself from the president during the preceding crisis, a move that his political independence might have facilitated, and which seems to have made him acceptable for the opposition in Congress and on the streets.

The association between the vice-president's affiliation and the outcome of a presidential interruption appears even clearer when such an event is brought about by the actions of outside parties, i.e. by a coup or an impeachment. In such cases, the final outcome appears closely related to the political affiliation of the vice-president. In the two cases of coups interrupting a presidency, the one vice-president who was allowed to assume power (Gustavo Noboa in Ecuador) was an independent who had been included on the presidential ticket of the ill-fated Jamil Mahuad, but who had come to oppose many of the government's policies. In the coup in Honduras in 2009, conversely, Manuel Zelaya's vice-president was a handpicked collaborator close to the president and fell with him.Footnote 52

Likewise, just as there is a connection between successful impeachment processes or congressional dismissals (a group in which we include the instance of the Guatemalan Congress stripping Otto Pérez Molina of his immunity from prosecution) and the presence of an external vice-president, all of the vice-presidents in such cases, except one, were able to assume power after their presidents had been forced out of office. The exception was Rosalía Arteaga in Ecuador, vice-president to Abdalá Bucaram in 1997, who kept power for only two days after Congress had dismissed Bucaram, after which she lost it to the president of Congress.

The patterns described above also hold true when we look at the survival rate of Latin American presidents with internal, external or no vice-presidents (Table 3). Between 1978 and 2016, there were 43 elected presidents in Latin America with ‘external’ vice-presidents. Ten of these governments, or 23 per cent, ended prematurely (excluding for health reasons). In comparison, of the 71 elected presidents who had vice-presidents from the president's party, only six, i.e. 8 per cent, saw the president permanently removed from office by crises or by external actors, and in no case through impeachment as detailed above.Footnote 53 In the countries without a vice-president, though, there has been only one presidential interruption during the period (the impeachment of Carlos Andrés Pérez in Venezuela).

Table 3. Interruptions to Elected Latin American Presidencies with External, Internal or No Vice-President, 1978–2016

Notes: These figures exclude interruptions for health reasons and deaths (five presidencies in total; see Table 2). Venezuela after 1999 and Honduras (except 2005–9) are also excluded due to their anomalous succession rules. The rank correlation coefficient (Spearman's Rho) between the status of the vice-president and the occurrence of an interruption is (–0.220) and significant at the 0.01 level (two-tailed).

While such figures demonstrate a possible correlation, they should not be confused with causation. As was shown above, features such as party fragmentation also correlate with external vice-presidents, and could by themselves increase the risks of presidential interruptions, leading to a spurious conclusion regarding the connection between the two factors. Similarly, although we can give anecdotal evidence of vice-presidents inviting such interruptions, or of how the opponents of deposed presidents reasoned, closer studies of the processes involved are required to substantiate any causality in this regard. What the data do show, however, is that the vice-presidency and the relationship of its titular to the president seem to represent important intermediary variables for explaining political developments during government crises.Footnote 54

In sum, then, Dilma Rousseff's fate does not appear extraordinary, but rather as another case of a little-noticed connection between vice-presidential affiliation and the risk of presidential interruptions. ‘External’ vice-presidents seem to attract interruptions and are also more likely to benefit from these than are vice-presidents drawn from the president's own party.

Conclusions

This article offers the first comprehensive overview of the vice-presidency in Latin America. By focusing on the institution's role during elections and presidential interruptions, we have tried to demonstrate the political relevance of this hitherto overlooked office.

Combining two original databases on the vice-presidency, we show how Latin American countries have struggled with the question of presidential succession and the incentives for tensions and betrayal that the office may imply. Having previously chosen vice-presidents from runners-up, or through separate ballots, which risked giving the vice-presidency to political opponents to the president, most countries eventually tried to solve this problem by electing president and vice-president on the same ticket. But electoral considerations seem to conspire against such a solution. Accordingly, giving the vice-presidency to persons from outside the president's own party has become a common strategy in Latin America, and seems to be related to the need to build presidential support in a multi-party setting.

It may not always be possible to equate the creation of such mixed electoral tickets with the separate election of the vice-president.Footnote 55 In particular, the former strategy would seem to require an element of ideological proximity and is often the result of formal cross-party alliances, which is not the case with the separate ballot. Yet the considerable pragmatism evident in choosing running-mates, combined with the ephemeral nature of many party alliances, means that the result of both mechanisms of election may be similar; namely the institution of designated successors to the president who have little interest in his or her permanence in office.

Accordingly, while the choice of external running-mates may be rational from an electoral perspective, it may also put the stability of the executive in danger. This suspicion is supported by our data, as vice-presidents from outside the president's party are associated with a markedly increased risk of presidential interruptions, particularly in the form of impeachment proceedings. Such external vice-presidents also seem to have a greater chance of benefitting from such interruptions.

The mechanism that underlies such developments appears to be related to the vice-president's role as a designated successor to the president. In fact, this succession formula makes presidential regimes confront some of the same succession dilemmas as those faced by authoritarian and monarchical regimes.Footnote 56 His or her privileged position as successor may induce the vice-president to conspire against the president, and/or embolden the latter's political opponents if they sense that there are internal divisions within the executive. Although they are clearly not helpless when confronting such situations, presidents have less room for manoeuvre given the vice-president's constitutional protection, which in most countries means that he or she cannot be removed by the president.

Yet the political stability that Latin America has enjoyed during recent decades means there are too few cases to draw a firm conclusion as to the causal impact of an ‘external’ vice-president on presidential survival. It is possible that countries with such vice-presidents are also more crisis-prone to begin with, because of higher degrees of party fragmentation, possibly weaker party systems and similar variables. Therefore, we cannot claim that the presence of a vice-president (even an external one) is by itself the cause of instability and presidential interruption. Rather, we see the institution as a possible intervening variable that may explain the outcome of periods of instability and attempted overthrows of the executive power. In such cases, the succession role of the vice-president, combined with the institution's ability to confer a degree of legitimacy on presidential interruptions, seem to make it more significant than has often been assumed, and it appears from our description that the question of whether the president and his/her deputy share partisan affiliation has particular importance in this regard.

In the end, though, a definitive answer as to the effects of having a president and a vice-president from different parties will require further research. Even so, we hope that the preceding pages indicate that vice-presidencies may wield considerably more political importance than is commonly assumed. More particularly, we believe that the above analysis indicates a number of possible further enquiries related to the vice-presidency. We still know little of the role of vice-presidents in presidential governments during normal times and what may explain potential variation in the office's performance across the region. Similarly, our assumptions above concerning the legitimacy and power that follows from different modes of electing the vice-president could certainly be discussed further, and more refined models developed in this regard, possibly combined with more detailed evidence on how the vice-president can serve as a vote-winner. On a related note, the fact that external vice-presidents are more common in multi-party settings indicates that the office may often have an important role in the formation and maintenance of government coalitions and should be considered by scholarly debates on such issues. Likewise, the extent to which the vice-president – particularly an external one – can serve as a mechanism for power-sharing and internal accountability within the executive power can offer a promising avenue for further enquiry regarding the role of the vice-president in the normal operation of the presidency. Related to this, and in a sense contrary to our analysis above, the importance of the vice-presidency for maintaining political stability by offering an institutionalised solution to presidential interruptions remains to be explored,Footnote 57 along with the quasi-parliamentary mechanisms evident in impeachment and dismissal processes that shift executive power from one party to another by way of the vice-president.

Appendix: Description of the Databases Used

The Latin American Presidential Succession and Vice-Presidency Database (LAPSVP)

Maintained by: Leiv Marsteintredet, University of Bergen.

Brief description: the database contains data on constitutional succession rules, rules on election and re-election of presidents and vice-presidents, and regulations of the vice-presidency for all countries in Latin America from independence with exception of constitutions under the Central American Federation and Panama before it became independent in 1904, and Cuba. Key variables are whether there is a designated successor (vice-president or designado) or not; the line of succession; how the successor is elected; the mode of succession (permanent/temporary); the duties of the successor/vice-president; and re-election rules for president and successor.

Years covered: 1819–2016.

Countries covered (since year): Argentina (1819), Bolivia (1826), Brazil (1824), Chile (1822) Colombia (1830), Costa Rica (1844), Dominican Republic (1844), Ecuador (1830), El Salvador (1841), Guatemala (1825), Honduras (1825), Mexico (1814), Nicaragua (1826), Panama (1904), Paraguay (1844), Peru (1823), Uruguay (1830), Venezuela (1821).

Number of cases: 256 (188 constitutions and 68 reforms).

Variables: country; year of constitution/reform; vice-president (presence/absence), number of vice-presidents/designates; who is presidential successor; rules of succession; rules of presidential election; rules of election of successor; electoral term president; electoral term vice-president; term limits president; term limits vice-president; rules of impeachment (majority required to depose president/vice-president; number of veto points in impeachment process); duties of vice-president.

Main sources: national constitutions, including constitutional reforms relating to rules of elections, re-election, term limits, presidential succession and the vice-presidency. The point of departure was the Cervantes virtual database on constitutions;Footnote 58 gaps have been filled in and the Cervantes virtual database has been double checked against specific country sources.

Data were gathered during 2015 and 2016. Mikal Rian assisted with the collection of the data.

Vice-Presidents in Latin America (VPILA)

Maintained by: Fredrik Uggla, Stockholm University.

Brief description: the database contains data on the two leading tickets in every presidential election, plus additional data on substitute vice-presidents. Apart from election results, it contains data on the personal and partisan background of the presidential and vice-presidential candidates, as well as information on possible interruptions to their periods in office.

Years covered: 1978–2016.

Countries covered (since year): Argentina (1983), Bolivia (1980), Brazil (1985), Colombia (1991), Costa Rica (1978), Dominican Republic (1978), Ecuador (1979), El Salvador (1984), Guatemala (1985), Honduras (2005), Nicaragua (1990), Panama (1994), Paraguay (1993), Peru (1980), Uruguay (1984).

Number of cases: 114 presidencies and 220 combinations of presidential and vice-presidential candidates.

Variables: country; year; presidential candidate's name; vice-presidential candidate's name; presidential candidate's party; presidential candidate's age; vice-presidential candidate's party prior to election campaign; relationship between presidential and vice-presidential candidate; vice-presidential candidate's age; electoral system; election results; number of candidates in presidential election; party fragmentation; party fragmentation in previous election; other information on president/vice-president; information on possible second vice-president.

Main sources: local newspapers; Dieter Nohlen (ed.): Elections in the Americas, 2 vols. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005); Manuel Alcántara and Flavia Freidenberg (eds.), Partidos Políticos de América Latina, 3 vols. (Salamanca: Ediciones Universidad, 2001); Alcántara, ‘Elections in Latin America 2009–2011’; Gallagher, ‘Election Indices Dataset’.

Data were gathered during 2016 and 2017.

Acknowledgements

The authors want to thank three anonymous reviewers as well as Andrés Rivarola and other participants at the research seminar on Latin America at Stockholm University for valuable comments. In addition, Marsteintredet wants to thank Mikal Rian for research assistance in constructing the LAPSVP database. Whilst the authors share responsibility for the content of the article, Marsteintredet has primarily contributed the historical data and analysis, while contemporary data and analysis is mainly Uggla's work.