Introduction

Ediacara-type macro-organisms are soft-bodied, morphologically complex eukaryotes that flourished in the last 30 million years of the Ediacaran Period (~571–539 Ma; Pu et al., Reference Pu, Bowring, Ramezani, Myrow, Raub, Landing, Mills, Hodgin and Macdonald2016; Linnemann et al., Reference Linnemann, Ovtcharova, Schaltegger, Gärtner, Hautmann, Geyer, Vickers-Rich, Rich, Plessen, Hofmann, Zieger, Krause, Kriesfeld and Smith2019). These macro-organisms are characterized by unusual body plans with few modern analogs. As such, their phylogenetic affinities have been highly debated, even at the kingdom level (Glaessner, Reference Glaessner, Moore, Robinson and Teichert1979; Seilacher, Reference Seilacher, Holland and Trendall1984; Retallack, Reference Retallack1994; Peterson et al., Reference Peterson, Waggoner and Hagadorn2003; Xiao and Laflamme, Reference Xiao and Laflamme2009; Erwin et al., Reference Erwin, Laflamme, Tweedt, Sperling, Pisani and Peterson2011). Among all Ediacara-type fossils, frondose forms are some of the most common fossils with wide geographic and long stratigraphic distributions (Laflamme and Narbonne, Reference Laflamme and Narbonne2008; Xiao and Laflamme, Reference Xiao and Laflamme2009). They are also phylogenetically diverse (Dececchi et al., Reference Dececchi, Narbonne, Greentree and Laflamme2017, Reference Dececchi, Narbonne, Greentree and Laflamme2018). Rangeomorph fronds (e.g., Charnia Ford, Reference Ford1958 and Fractofusus Gehling, Reference Gehling and Narbonne2007) dominate the Avalon Assemblage, and arboreomorph fronds (e.g., Arborea Glaessner and Wade, Reference Glaessner and Wade1966) are also common. In the younger White Sea and Nama assemblages, arboreomorph and erniettomorph fronds overtake rangeomorphs as the dominant fronds, although rangeomorphs continue to persist (Waggoner, Reference Waggoner1999; Boag et al., Reference Boag, Darroch and Laflamme2016; Droser et al., Reference Droser, Tarhan and Gehling2017).

Many Ediacaran fronds are characterized by a stem attached to a leaf-like petalodium at the apical end, and a discoid structure at the basal end, suggesting a benthic lifestyle. Delicate structures of the petalodium could have facilitated osmotrophic feeding (Laflamme et al., Reference Laflamme, Xiao and Kowalewski2009, Reference Laflamme, Gehling and Droser2018; Hoyal Cuthill and Conway Morris, Reference Hoyal Cuthill and Conway Morris2014). But the possibility that they were photoautotrophs has been excluded because of their occurrence in deep-marine environments below the photic zone (Wood et al., Reference Wood, Dalrymple, Narbonne, Gehling and Clapham2003). Laflamme and Narbonne (Reference Laflamme and Narbonne2008) considered Ediacaran fronds as an artificial group, comprising taxa from different phylogenetic lineages, and a recent cladistic analysis by Dececchi et al. (Reference Dececchi, Narbonne, Greentree and Laflamme2017) found support for the monophyly of three major frond groups (i.e., rangeomorphs, arboreomorphs, and erniettomorphs; see Laflamme and Narbonne, Reference Laflamme and Narbonne2008; Erwin et al., Reference Erwin, Laflamme, Tweedt, Sperling, Pisani and Peterson2011). Xiao and Laflamme (Reference Xiao and Laflamme2009), Budd and Jensen (Reference Budd and Jensen2015), and Dunn et al. (Reference Dunn, Liu and Donoghue2018) each proposed that rangeomorph fronds are probably metazoans or stem-group metazoans. Hoyal Cuthill and Han (Reference Hoyal Cuthill and Han2018) suggested that some Ediacaran fronds might be metazoans on the basis of their purported morphological similarities to the Cambrian animal fossil Stromatoveris Shu, Conway Morris, and Han in Shu et al., Reference Shu, Morris, Han, Li, Zhang, Hua, Zhang, Liu, Guo, Yao and Yasui2006. Recent studies also suggest that arboreomorphs might be animals as well. Dunn et al. (Reference Dunn, Liu and Gehling2019a), for example, concluded that Arborea is a colonial organism belonging to the total-group Eumetazoa, based on evidence for tissue differentiation, fascicled branching arrangement, probable fluid-filled holdfast, and apical-basal and front-back differentiation.

Laflamme et al. (Reference Laflamme, Gehling and Droser2018) summarized the taxonomic history of Arborea. Arborea arborea (Glaessner in Glaessner and Daily, Reference Glaessner and Daily1959) Glaessner and Wade, Reference Glaessner and Wade1966 was first described in the genus Rangea. Glaessner and Wade (Reference Glaessner and Wade1966) recognized its difference from Rangea and erected the new genus Arborea to host this species. Arborea is a frondose fossil with a bifoliate petalodium, a prominent central stalk, parallel primary branches, and sometimes a discoidal holdfast.

Arborea was once synonymized with Charniodiscus Ford, Reference Ford1958 based on their morphological similarities (Jenkins and Gehling, Reference Jenkins and Gehling1978). However, more recent studies of the original material of Charniodiscus suggest that the holotype of its type species, Charniodiscus concentricus Ford, Reference Ford1958, could be a multifoliate frond (Dzik, Reference Dzik2002; Brasier and Antcliffe, Reference Brasier and Antcliffe2009) with a fractal branching pattern that resembles that of Rangea (Brasier and Antcliffe, Reference Brasier and Antcliffe2009). However, all other species placed in the genus Charniodiscus seem to be bifoliate and do not appear to have a fractal branching pattern. Laflamme et al. (Reference Laflamme, Gehling and Droser2018) considered these characteristics to represent fundamental differences in construction and reassigned Charniodiscus arboreus and Charniodiscus oppositus Jenkins and Gehling, Reference Jenkins and Gehling1978, which are based on Australian specimens, to the genus Arborea. The genus Charniodiscus therefore includes five species, Charniodiscus longus Glaessner and Wade, Reference Glaessner and Wade1966, Charniodiscus spinosus Laflamme, Narbonne, and Anderson, Reference Laflamme, Narbonne and Anderson2004, Charniodiscus procerus Laflamme, Narbonne, and Anderson, Reference Laflamme, Narbonne and Anderson2004, Charniodiscus yorgensis Borchvardt and Nessov, Reference Borchvardt and Nessov1999, and the type species Charniodiscus concentricus. Khatyspytia grandis Fedonkin, Reference Fedonkin, Sokolov and Ivanovskiy1985 from the terminal Ediacaran Khatyspyt Formation in northern Siberia (Fedonkin, Reference Fedonkin, Sokolov and Ivanovskiy1985; Grazhdankin, Reference Grazhdankin2014) is said to be “indistinguishable from the Avalon species Charniodiscus procerus” (Grazhdankin et al., Reference Grazhdankin, Balthasar, Nagovitsin and Kochnev2008, p. 805), but a formal taxonomic treatment has not been published. Further study is needed to determine the taxonomic relationship (or lack thereof) between these Charniodiscus spp. and Arborea. A systematic revision of these Charniodiscus spp. is beyond the scope of the present study, but the morphological differences between Charniodiscus and Arborea spp. are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Comparison of taxa of Charniodiscus and Arborea. NP = not preserved; * = type species; - = no data. References: 1 = Ford (Reference Ford1958); 2 = Brasier and Antcliffe (Reference Brasier and Antcliffe2009); 3 = Laflamme et al. (Reference Laflamme, Narbonne and Anderson2004); 4 = Glaessner and Wade (Reference Glaessner and Wade1966); 5 = Ivantsov (Reference Ivantsov2016); 6 = Glaessner and Daily (Reference Glaessner and Daily1959); 7 = Hofmann et al. (Reference Hofmann, O'Brien and King2008); 8 = Laflamme et al. (Reference Laflamme, Gehling and Droser2018); 9 = Jenkins and Gehling (Reference Jenkins and Gehling1978).

To contribute to our understanding of Ediacaran frondose fossils, here we provide a systematic description of new arboreomorphs preserved in limestone of the terminal Ediacaran Shibantan Member in the Yangtze Gorges area of South China. The new material includes four species of Arborea: Arborea arborea, Arborea denticulata new species, Arborea sp. A, and Arborea sp. B. These taxa represent the first formal report of Arborea from terminal Ediacaran carbonate facies, and together with possible arboreomorphs from the Khatyspyt Formation in northern Siberia described as Khatyspytia grandis (Fedonkin, Reference Fedonkin, Sokolov and Ivanovskiy1985; Grazhdankin et al., Reference Grazhdankin, Balthasar, Nagovitsin and Kochnev2008; Grazhdankin, Reference Grazhdankin2014), they help us to better understand the stratigraphic, ecological, and taphonomic ranges of the Arboreomorpha.

Geological setting

Cryogenian-Ediacaran successions crop out around the Huangling anticline in the Yangtze Gorges area (Fig. 1.1). Ediacaran successions in this area, consisting of the Doushantuo and Dengying formations, are underlain by the Cryogenian Nantuo Formation and overlain by the Cambrian Yanjiahe Formation (Fig. 1.2). The late Ediacaran Dengying Formation represents the terminal Ediacaran (551–539 Ma) sediments in the Yangtze Gorges area (Condon et al., Reference Condon, Zhu, Bowring, Wang, Yang and Jin2005; Schmitz, Reference Schmitz, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2012). It consists of carbonate rocks deposited in sub- to supratidal inner-ramp environments (Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Xiao, Gill, Schiffbauer, Chen, Zhou and Yuan2014; Duda et al., Reference Duda, Zhu and Reitner2016) on a shallow-water carbonate platform (Cao et al., Reference Cao, Tang, Xue, Yu, Yin and Zhao1989; Zhou and Xiao, Reference Zhou and Xiao2007). The Dengying Formation contains three members, in ascending order, the Hamajing, Shibantan, and Baimatuo members (Fig. 1.2).

Figure 1. Geological map (1) and stratigraphic column (2) showing the locality of the Wuhe quarry [black dot in (1)] and the stratigraphic range of Ediacara-type fossils [black star in (2)]. Arborea fossils reported in this paper were collected from two horizons at 0.5 m and 20 m above the base of the Shibantan Member. Modified from Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Zhou, Xiao, Wang, Guan, Hua and Yuan2014). Geochronometric data from Condon et al. (Reference Condon, Zhu, Bowring, Wang, Yang and Jin2005) and Schmitz (Reference Schmitz, Gradstein, Ogg, Schmitz and Ogg2012). Fm = Formation; Mbr = Member; U-Pb = uranium-lead radiometric dating.

The fossils described in this paper were collected at the Wuhe section in the Yangtze Gorges area (Fig. 1.1). There, the Hamajing Member is ~24 m thick and is mostly composed of medium- to thick-bedded whitish-gray dolostones with chert concretions and thinly bedded chert bands. Sedimentary evidence for subaerial exposure, e.g., tepee structures and dissolution vugs, is common in the Hamajing Member (Zhou and Xiao, Reference Zhou and Xiao2007; Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Xiao, Gill, Schiffbauer, Chen, Zhou and Yuan2014). Additional evidence includes calcite pseudomorphs after gypsum crystals (Duda et al., Reference Duda, Zhu and Reitner2016), consistent with the shallow peritidal environment interpretation (e.g., Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhou, Meyer, Xiang, Schiffbauer, Yuan and Xiao2013, Reference Chen, Zhou, Xiao, Wang, Guan, Hua and Yuan2014; Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Xiao, Gill, Schiffbauer, Chen, Zhou and Yuan2014).

The Shibantan Member at Wuhe is ~150 m thick and consists of blackish-gray, thin- to medium-bedded, bituminous limestone, intercalated with thin chert bands and concretions. Weathered outcrops often display a rusty or ochre color, probably derived from the oxidative weathering of pyrite. The Shibantan Member is generally characterized by microlaminated limestones deposited in subtidal environments, with occasional occurrence of stromatolitic structures indicating deposition in the photic zone, as well as hummocky cross-stratification and lenticular rip-up clasts indicating depositional environments above the storm-wave base (Sun, Reference Sun1986; Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Xiao, Gill, Schiffbauer, Chen, Zhou and Yuan2014; Duda et al., Reference Duda, Zhu and Reitner2016; Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, She, Wang, Li, Ouyang, Cao, Mason and Du2020). Dark, millimeter-scale, clay-rich, crinkled laminae are also common in the Shibantan Member. These crinkled laminae have been interpreted as microbial mats (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhou, Meyer, Xiang, Schiffbauer, Yuan and Xiao2013), which have been hypothesized to be an important factor facilitating the preservation of soft-bodied Ediacaran fossils (Gehling, Reference Gehling1999; Callow and Brasier, Reference Callow and Brasier2009; Laflamme et al., Reference Laflamme, Schiffbauer, Narbonne and Briggs2011). A number of macrofossil taxa have been reported from the Shibantan Member, including classical Ediacara-type fossils (e.g., Rangea Gürich, Reference Gürich1929, Pteridinium Gürich, Reference Gürich1930, and Hiemalora Fedonkin, Reference Fedonkin1982; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhou, Xiao, Wang, Guan, Hua and Yuan2014), macroalgal fossils such as Vendotaenia Gnilovskaya, Reference Gnilovskaya1971 (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Xing, Ding, Liu, Zhao, Zhang, Meng, Yin, Ning and Han1988), problematic fossils such as Yangtziramulus Shen et al., Reference Shen, Xiao, Zhou and Yuan2009 (Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Shen, Zhou, Xie and Yuan2005) and Curviacus Shen et al., Reference Shen, Xiao, Zhou, Dong, Chang and Chen2017, as well as remarkably diverse trace fossils that provide exciting opportunities to study early animal evolution (Zhao et al., Reference Zhao, Xing, Ding, Liu, Zhao, Zhang, Meng, Yin, Ning and Han1988; Weber et al., Reference Weber, Steiner and Zhu2007; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhou, Meyer, Xiang, Schiffbauer, Yuan and Xiao2013, Reference Chen, Chen, Zhou, Yuan and Xiao2018, Reference Chen, Zhou, Yuan and Xiao2019; Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Xiao, Gill, Schiffbauer, Chen, Zhou and Yuan2014; Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Chen, Zhou and Yuan2019).

The Baimatuo Member at Wuhe is ~60 m thick and is composed of medium- to thick-bedded light gray dolostones. Similar to the Hamajing Member, dissolution structures, tepees, and intraclasts are common in the Baimatuo Member, indicating deposition in a peritidal environment (Zhou and Xiao, Reference Zhou and Xiao2007).

Materials and methods

The Arborea specimens described here were collected from the Shibantan limestone at the Wuhe quarry (30.789°N, 110.051°E) with known stratigraphic orientation (Fig. 1.1). Two fossiliferous horizons were recorded, at ~0.5 m and 20 m above the base of the Shibantan Member. Petrographic thin sections were prepared for one Arborea arborea specimen and observed under a transmitted light microscope. One of the specimens (NIGP 170063, Fig. 2.1) was previously illustrated by Droser et al. (Reference Droser, Tarhan and Gehling2017, fig. 1, top left), but all other specimens are illustrated here for the first time.

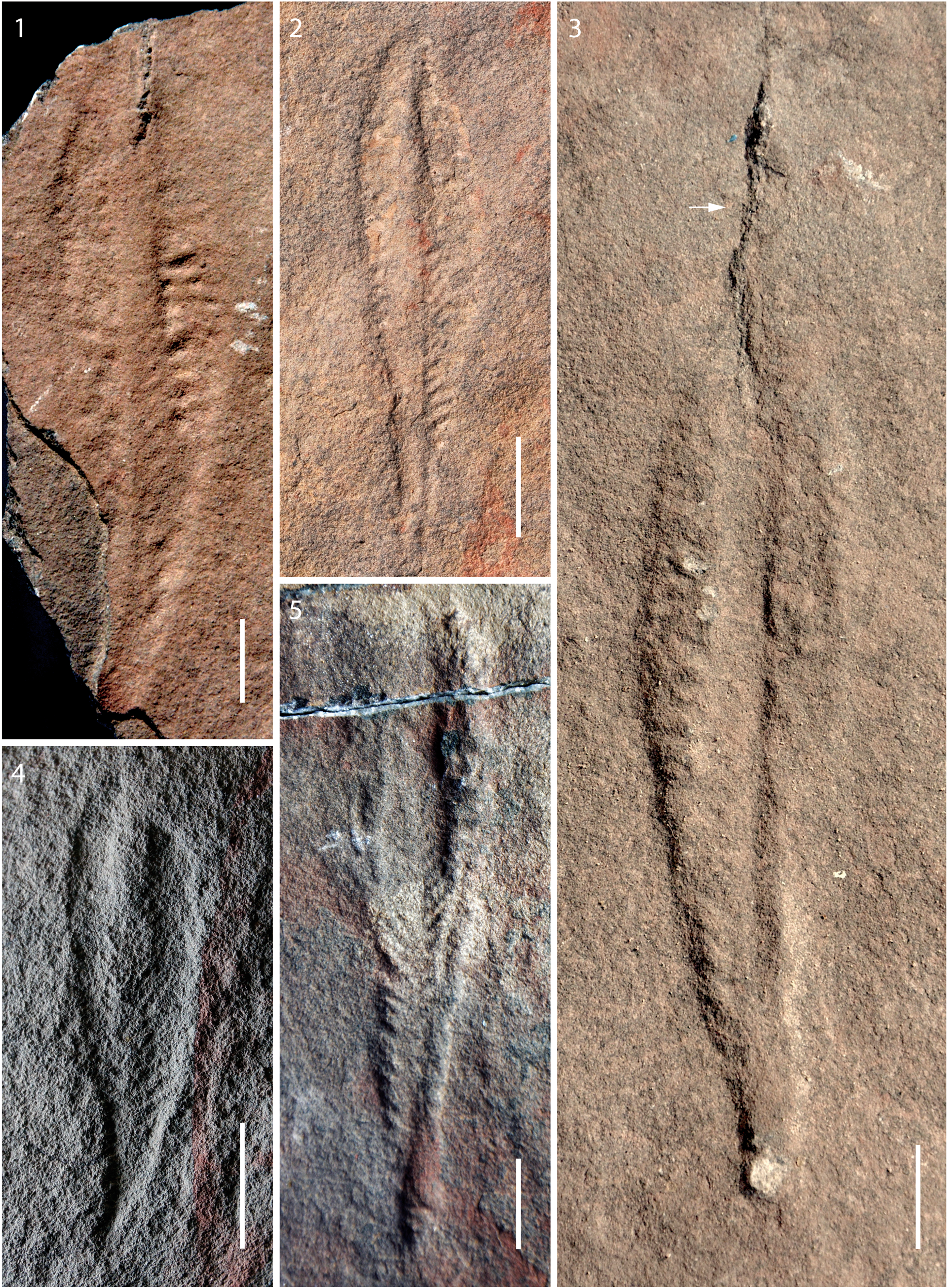

Figure 2. Arborea arborea from the Shibantan limestone: (1) nearly complete specimen with central stalk and primary branches preserved in positive relief, bed sole view, NIGP 170063; (2) specimen with stalk preserved as central furrow, bed top view, field specimen; (3) counterpart of specimen in (1), spine-like structure (arrow) extends beyond apex of the petalodium; (the spine-like structure appears to be a crack rather than a biological feature, and no such structure is present in other specimens; bed top view, NIGP 170063; (4) small but nearly complete specimen, with stalk that does not extend through entire length of the petalodium, bed sole view, NIGP 170065; (5) nearly complete specimen, bed top view, NIGP 170066. Scale bars = 1 cm.

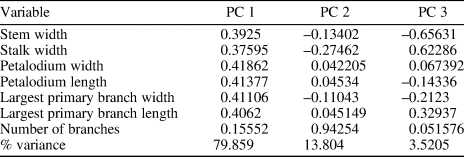

A principal component analysis (PCA) was conducted to assist taxonomic identification and to evaluate morphological similarities among Arborea species. The analysis was based on morphological data collected from 20 specimens with a complete petalodium, including eight Arborea arborea specimens and one Arborea denticulata n. sp. specimen from South China (this paper), three Arborea arborea specimens from South Australia (Laflamme et al., Reference Laflamme, Gehling and Droser2018; Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Liu and Gehling2019a), and five Charniodiscus sp. specimens and three “Charniodiscus” arboreus specimens from Newfoundland (Laflamme et al., Reference Laflamme, Narbonne and Anderson2004; Hofmann et al., Reference Hofmann, O'Brien and King2008). Measurements of Newfoundland specimens were taken on retrodeformed photos (with elliptical holdfasts restored to their original circular shape; Hofmann et al., Reference Hofmann, O'Brien and King2008) because the host sediments are known to have been tectonically deformed. One exception is the specimen ROM 36504, which was discovered on a loose block near Portugal Cove South and contains a circular holdfast indicating locally negligible shearing (Laflamme et al., Reference Laflamme, Narbonne and Anderson2004). No retrodeformation was performed on specimens from South Australia and South China, where discoidal holdfasts are mostly circular in shape, indicating very little tectonic deformation. Seven morphological variables were measured, including the widths of the stem (measured at the base of the petalodium) and stalk, the widths and lengths of the petalodium and the largest primary branch, and the number of primary branches (Table 2). The biometric data were presented in cross-plots and fed into PCA analysis. The PCA analysis was performed using the PAST software (Hammer et al., Reference Hammer, Harper and Ryan2001).

Table 2. Variable loadings and variance partition among the first three PCs.

Repository and institutional abbreviation

All illustrated specimens are deposited in the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology (NIGP), Nanjing, China. Additional specimens for PCA and biometric analysis (Table 3) are housed at The Royal Ontario Museum (ROM), Toronto, Canada; the Provincial Museum of Newfoundland and Labrador (NFM F), St. John's, Canada; and the South Australian Museum (SAM P), Adelaide, Australia.

Table 3. Biometric data for measured specimens. N = Newfoundland; N/A = not available; SA = South Australia; SC = South China.

Systematic paleontology

Genus Arborea Glaessner and Wade, Reference Glaessner and Wade1966

Type species

Arborea arborea (Glaessner in Glaessner and Daily, Reference Glaessner and Daily1959) Glaessner and Wade, Reference Glaessner and Wade1966.

Arborea arborea (Glaessner in Glaessner and Daily, Reference Glaessner and Daily1959) Glaessner and Wade, Reference Glaessner and Wade1966, emended

Figure 2

- Reference Glaessner and Daily1959

Rangea arborea Glaessner in Glaessner and Daily, p. 383–387, pls. 43.1–43.3, 44.1–44.3, 45.1, 45.2, 46.1.

- Reference Glaessner and Wade1966

Arborea arborea; Glaessner and Wade, p. 619–620, pl. 102, figs. 1, 2.

- Reference Jenkins and Gehling1978

Charniodiscus arboreus; Jenkins and Gehling, fig. 3.

- Reference Glaessner, Moore, Robinson and Teichert1979

Charniodiscus arboreus; Glaessner, fig. 12.2c.

- Reference Jenkins, Davies, Twidale and Tyler1996

Charniodiscus arboreus; Jenkins, p. 36, fig. 4.2a, b, 4.3.

- Reference Dzik2002

Charniodiscus (Arborea) arboreus; Dzik, fig. 4.

- Reference Laflamme, Narbonne and Anderson2004

Charniodiscus arboreus; Laflamme et al., p. 832, fig. 4.5.

- Reference O'Brien and King2004

frond-like fossils; O'Brien and King, p. 206, fig. 3A, 3B, pls. 3C, 4A.

- Reference Hofmann, O'Brien and King2008

Charniodiscus arboreus; Hofmann et al., p. 20, fig. 16.7–16.8.

- Reference Hofmann, O'Brien and King2008

Charniodiscus sp.; Hofmann et al., p. 23, fig. 16.1–16.6.

- Reference Gehling and Droser2013

Charniodiscus sp.; Gehling and Droser, fig. 2c.

- Reference Chen, Zhou, Xiao, Wang, Guan, Hua and Yuan2014

Charniodiscus; Chen et al., fig. 3c.

- Reference Droser, Tarhan and Gehling2017

Arborea; Droser et al., fig. 1 (top left specimen).

- Reference Laflamme, Gehling and Droser2018

Arborea; Laflamme et al., p. 4–7, figs. 1–8.

- Reference Dunn, Liu and Gehling2019a

Arborea; Dunn et al., figs. 1–5.

Holotype

SAM P 12891, from the Ediacaran Member of the Rawnsley Quartzite, Flinders Ranges, South Australia.

Emended diagnosis (from Laflamme et al., Reference Laflamme, Narbonne and Anderson2004)

Arborea with ovate petalodium and at least 14 primary branches alternating on either side of stalk. Primary branches approximately uniform in width throughout petalodium, with distal branches slightly narrower than proximal ones.

Occurrence

Shibantan Member, Dengying Formation, Yangtze Gorges area of South China (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhou, Xiao, Wang, Guan, Hua and Yuan2014); Mistaken Point and Fermeuse formations, Newfoundland, Canada (Laflamme et al., Reference Laflamme, Narbonne and Anderson2004; Hofmann et al., Reference Hofmann, O'Brien and King2008); Rawnsley Quartzite, Flinders Ranges, South Australia (Glaessner and Wade, Reference Glaessner and Wade1966).

Description

The Shibantan specimens are characterized by a bifoliate frond with 15–21 primary branches emanating from a prominent stalk at 40–90°. Oblanceolate petalodium tapers toward an apex at the distal end, connecting to a basal disc (holdfast) via a stem at the other end. The best-preserved specimen, consisting of a part and counterpart (NIGP 170063, Fig. 2.1, 2.3), is nearly complete, with fully preserved petalodium but missing the stem and holdfast. The petalodium is 80 mm in length, 25 mm in width, preserved as positive hyporelief in limestone. Two rows of primary branches attach alternately to a central stalk. Primary branches are better preserved on one side of the petalodium (Fig. 2.1, right), where 16 primary branches are discernable. Primary branches are 1.6–3.3 mm in width (measured along the length of the stalk) and 6.7–11.6 mm in length (measured perpendicular to the length of the stalk). The length/width ratio of primary branches is 3.5–4.2 (3.5 for the largest primary branch). Branching angles of primary branches increase from 40° at the base of the petalodium to almost 90° at the apex. Secondary branches were not discernable. The stalk is parallel-sided, 7 mm wide. Other specimens (three of which are illustrated in Fig. 2.2, 2.4, 2.5) show a similar petalodium shape, with a petalodium length of 40–262 mm (mean 87 mm, N = 16) and petalodium width of 12–51 mm (mean 22 mm, N = 16). The width of the central stalk also varies among specimens. In a small specimen (Fig. 2.4), the central stalk does not run through the entire length of the petalodium.

Materials

Total 17 specimens.

Remarks

Laflamme et al. (Reference Laflamme, Gehling and Droser2018) described the diverse morphologies of the central stalk in Australian Arborea specimens, including a condition in which the primary branches originate from within the boundaries of the central stalk (Laflamme et al., Reference Laflamme, Gehling and Droser2018, fig. 3.2). Dunn et al. (Reference Dunn, Liu and Gehling2019a) suggested that some of this variation is caused by composite molding of rotated branch connection points onto a cylindrical stalk. Some Shibantan specimens exhibit a similar stalk condition (e.g., Fig. 2.1). The morphological variation of the stalk could in part reflect taphonomic differences. For example, in the Australian specimens, the stalk can be sinuous when the primary branches originate from within the boundaries of the central stalk, and Laflamme et al. (Reference Laflamme, Gehling and Droser2018) considered this a taphonomic artifact resulting from compression of an originally cylindrical stalk and the composite molding of alternating primary branches. However, the Shibantan specimens typically have a parallel-sided stalk and their primary branches tend to be superimposed on the stalk. It is uncertain whether the differences in stalk morphology between the Australian and Chinese specimens are biological (e.g., different degrees to which the proximal end of the primary branches encroach onto the central stalk) or taphonomic (e.g., perhaps slight rotation of the cylindrical stalk during compression).

Some Australian Arborea specimens show a peapod-like or teardrop-like architecture of secondary branches (e.g., Laflamme et al., Reference Laflamme, Gehling and Droser2018; Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Liu and Gehling2019a), but these structures are not preserved in the Shibantan Arborea specimens. The presence or absence of such structures can be taphonomic variation, a dorsal/ventral differentiation of the petalodium (i.e., peapod-like structures are enveloped by a membrane and only visible on the dorsal side; Jenkins and Gehling, Reference Jenkins and Gehling1978; Laflamme et al., Reference Laflamme, Gehling and Droser2018; Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Liu and Gehling2019a), or an ontogenetic variation (i.e., peapod-like structures only developed in larger, developmentally mature specimens). The Shibantan Arborea specimens are generally smaller than the Australian specimens, and their preservation is relatively poor, with no secondary branches discernable. Thus, the absence of the peapod-like structures in the Shibantan specimens is probably related to either ontogenetic or taphonomic variation.

Hofmann et al. (Reference Hofmann, O'Brien and King2008) reported Charniodiscus sp. from the Bonavista Peninsula, Newfoundland, Canada; it is very similar to Arborea arborea except that it has 14–18 primary branches, whereas Arborea arborea has > 20 primary branches as diagnosed by Laflamme et al. (Reference Laflamme, Narbonne and Anderson2004). However, one specimen assigned to Arborea arborea (by Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Liu and Gehling2019a, fig. 3A) from South Australia has only 19 primary branches. Hofmann et al. (Reference Hofmann, O'Brien and King2008) also considered possibly emending the diagnosis of Arborea arborea to accommodate specimens with < 20 branches. This emendation is formalized here and is further supported by morphometric data described below (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. Principal components analysis (PCA) and biometric cross-plots for Arborea arborea, Arborea denticulata n. sp., and Charniodiscus sp. of Hofmann et al. (Reference Hofmann, O'Brien and King2008): (1) PC 1 versus PC 2; the outlier to the right represents an exceptionally large specimen from South Australia; (2) PC 2 versus PC 3; Arborea denticulata n. sp. is separated from other taxa along PC 2 and PC 3 (refer to Table 2 for variable loadings and variance partition among the first three PCs); (3) cross-plot of petalodium width versus length; (4) Cross-plot of width versus length of the largest primary branch in each measured specimen; this plot includes measurements of two additional Arborea denticulata n. sp. specimens, NIGP 170068 and 173165, which are not included in PCA and (3) because their petalodia are incompletely preserved. Data sources: Arborea arborea (N = 8; this study) and Arborea denticulata n. sp. [N = 1 in (1–3), N = 3 in (4); this study] from South China, Arborea arborea (N = 3) from South Australia (Laflamme et al., Reference Laflamme, Gehling and Droser2018; Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Liu and Gehling2019a), Charniodiscus sp. (N = 5) and Charniodiscus arboreus (N = 3) from Newfoundland (Laflamme et al., Reference Laflamme, Narbonne and Anderson2004; Hofmann et al., Reference Hofmann, O'Brien and King2008).

Figure 4. Arborea denticulata n. sp. from the Shibantan limestone: (1–3) holotype, NIGP 170067: (1, 2) part and counterpart, bed sole and bed top views, respectively; arrow points to where basal disc connects with stem (3) magnified view of boxed area in (1) photographed in different lighting direction, showing shiny silver-colored carbonaceous compression of a vendotaenid fossil (arrow) directly underlying the Arborea specimen; (4) incomplete specimen, bed sole view, NIGP 170068; (5) incomplete specimen, bed sole view, NIGP 173165. Scale bars = 1 cm (1, 2, 4, 5); 0.5 mm (3).

Results of principal component analysis (PCA) show that the first three principal components (PC) are responsible for 97.2% of the total variance observed (Table 2). PC 1 explains ~80% of the total variance; the uniform and positive loadings for all variables (Table 2) suggest that it mainly reflects body size. PC 2 and PC 3 could reflect morphological variations among different species. PC 2 explains ~14% of the total variance. The number of primary branches and the stalk width have the greatest positive and negative loadings, respectively, on PC 2 (Table 2). PC 3 explains ~4% of the total variance. The stalk width and the largest primary branch length have large positive loadings whereas stem width has the greatest negative loading on PC3 (Table 2). Figure 3.1 and 3.2 plots all specimens in the PC 1/2 and PC 2/3 space, respectively. Arborea arborea from South China and South Australia share a similar morphospace as do Charniodiscus sp. and Charniodiscus arboreus from Newfoundland in these plots (Fig. 3.1, 3.2), supporting the taxonomic treatment that they all belong to the same species. This taxonomic treatment is further supported by biometric data (Table 3) and biometric plots (Fig. 3.3, width versus length of petalodium; Fig. 3.4, width versus length of the largest primary branch). In contrast, Arborea denticulata n. sp. is separated from other taxa along PC 2 and PC 3 (Fig. 3.2) and has a distinctly lower length/width ratio of the largest primary branch (Fig 3.4).

Arborea denticulata new species

Figure 4

Holotype

NIGP 170067.

Diagnosis

Arborea with elliptical petalodium consisting of rectangular primary branches attached alternately to a central stalk at 75–90°. Primary branches separated from each other by distinct furrows. Petalodium attached to basal disc by a stem.

Occurrence

Shibantan Member, Dengying Formation, Yangtze Gorges area of South China.

Description

Holotype (Fig. 4.1, 4.2) is a bifoliate frond, 89 mm long (measured from the center of the basal disc to the apex), preserved as negative epirelief and positive hyporelief. The petalodium is 60 mm in length, 18 mm in width, tapers toward an apex at the distal end, and is connected to a discoidal holdfast at the basal end through a stem. Each side of the petalodium consists of at least 13 primary branches, alternately anchored to the central stalk at nearly right angles (75–90°). Primary branches are rectangular, separated from each other by transverse grooves. Primary branches are 2.9–5.8 mm in width (measured along the length of the stalk) and 6.0–7.9 mm in length (measured perpendicular to the length of the stalk), with a length/width ratio of 1.4–2.1. The largest primary branch has a length/width ratio of 1.4 and widens abaxially (away from the stalk), from 3 mm to 5 mm. No discernable subdivisions of primary branches were observed. The petalodium is attached to a basal holdfast through a stem. The stem is 29 mm long, representing approximately one-third of the entire length of the specimen, narrows slightly toward the petalodium, and widens slightly toward the holdfast. The discoidal holdfast is 12 mm in diameter. It has a circular outer ridge and a central boss.

In addition to the holotype, there are two other incomplete specimens (NIGP 170068 and 173165; Fig. 4.4, 4.5) collected from the Shibantan Member. Although the stem and holdfast are not preserved in these specimens, the features of their petalodia are consistent with the diagnosis of Arborea denticulata n. sp. Their petalodia are 25 mm and 106.8 mm long and 10 mm and 39.8 mm wide, respectively. Their largest primary branches are 3.4 mm and 12.3 mm wide (measured along the length of the stalk) and 4.8 mm and 19.6 mm long, with a length/width ratio of 1.4 and 1.6, respectively. The branching angles of primary branches emerging from the central stalk vary from 72–90°.

A reconstruction of Arborea denticulata n. sp. based mainly on the holotype (NIGP 170067) is presented in Figure 5.

Figure 5. Reconstruction of Arborea denticulata n. sp. Scale bar = 1 cm.

Etymology

From denticulata (Latin, tooth), in reference to the tooth-like rectangular shape of the primary branches.

Materials

Three specimens.

Remarks

Arborea denticulata n. sp. can be distinguished from Arborea arborea by its fewer primary branches and lower length/width ratio of the largest primary branch. The PCA analysis and biometric cross-plot (Fig. 3.2, 3.4) also show that Arborea denticulata n. sp. is distinct from Arborea arborea. Arborea denticulata n. sp. can also be distinguished from Charniodiscus yorgensis, beautifully illustrated by Ivantsov (Reference Ivantsov2016), by its possession of fewer primary branches, which are rectangular in shape. In contrast with the multifoliate frond of Charniodiscus concentricus (see Dzik, Reference Dzik2002; Brasier and Antcliffe, Reference Brasier and Antcliffe2009), Arborea denticulata n. sp. is bifoliate and does not display a rangeomorph-type branching pattern. The overall morphology of Arborea denticulata n. sp. resembles Charniodiscus procerus in that both have < 15 primary branches (Table 1). But the latter differs in that the stem occupies a greater portion (mean 39%, N = 14; Laflamme et al., Reference Laflamme, Narbonne and Anderson2004) of the entire length of the specimen, the stalk is more prominent, and diverging angles of the primary branches are more variable (45–90°). Finally, Arborea denticulata n. sp. differs from Charniodiscus spinosus in its ovate petalodium and the lack of a pronounced distal spine that is present in the latter species.

Arborea sp. A

Figure 6.1–6.4

- Reference Shao, Chen, Zhou and Yuan2019

unnamed frond; Shao et al., fig. 2A–E.

Figure 6. Arborea sp. A and Arborea sp. B from the Shibantan limestone: (1, 2) part and counterpart of Arborea sp. A with a prominent tentacle-bearing Hiemalora-like basal disc, NIGP 169472: (1) negative relief on bed top; (2) positive relief on bed sole; (3) magnified view of boxed area in (1), showing primary branches (arrows); (4) magnified view of boxed area in (2), showing the apical spine (arrows); (5, 6) almost complete specimen of Arborea sp. B, bed sole view, NIGP 170064: (5) stem (arrowhead) connecting petalodium and tentacle-bearing Hiemalora-like basal disc (arrow); (6) magnified view of boxed area in (5), showing that the apical end of the petalodium is bent to the right (arrow). Scale bars = 1 cm.

Occurrence

Shibantan Member, Dengying Formation, Yangtze Gorges area of South China.

Description

Only one specimen is assigned to this open nomenclature. The frond is 14.3 cm long (measured from the center of the basal disc to the apical spine), consisting of a petalodium, a Hiemalora-like holdfast, and a connecting stem. The petalodium is elliptical, 8.2 cm long, 3.2 cm wide, composed of two rows of primary branches (Fig. 6.3). Each row consists of 6–8 primary branches. The primary branches are parallelogram-shaped, meeting alternately at a cylindrical central stalk. The branching angles are 45–90°. No secondary branches are preserved. The distal end of the petalodium tapers to an apical spine (Fig. 6.4). The stem is 6.1 cm in length, 1.3 cm in width, and connected to the outer rim of the holdfast. The holdfast resembles Hiemalora. The central part of the holdfast is a disc, 2.5 cm in diameter, flat, and without concentric rings. Approximately 27 tentacle-like appendages radiate from the outer rim of the central disc. The tentacle-like appendages are relatively uniform in width (1.0–1.3 mm; mean 1.2 mm, N = 27) but vary in length (4.9–43.8 mm; mean 16.5 mm, N = 27). The tentacle-like structures tend to be directed, perhaps taphonomically, toward the petalodium and they sometimes overlap each other. The rows of primary branches are preserved as negative epireliefs whereas the central stalk, stem, and holdfast are preserved as positive epireliefs on the top bedding surface.

Materials

One specimen.

Remarks

The overall morphology of Arborea sp. A resembles Charniodiscus spinosus in petalodium shape, the number of primary branches, and the presence of an apical spine (Table 1). However, Charniodiscus spinosus exhibits a greater ratio of frond length to stem length (mean 5.77, N = 28; Laflamme et al., Reference Laflamme, Narbonne and Anderson2004; Table 1), whereas the ratio is 1.4 for Arborea sp. A. This difference, however, could represent either taxonomic or ecophenotypic variation (Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Wilby, Kenchington, Grazhdankin, Donoghue and Liu2019b). Moreover, the discoidal holdfast of Charniodiscus spinosus lacks tentacle-like structures. Kenchington and Wilby (Reference Kenchington and Wilby2017) have shown that the presence/absence of tentacle-like structures in the holdfast of Ediacaran fronds could represent a species-level but not a genus-level difference, as in the case of Primocandelabrum Hofmann, O'Brien, and King, Reference Hofmann, O'Brien and King2008. Indeed, it is possible that Charniodiscus spinosus might need to be transferred to the genus Arborea given that the type species, Charniodiscus concentricus, is characterized by a multifoliate frond (Dzik, Reference Dzik2002; Brasier and Antcliffe, Reference Brasier and Antcliffe2009). Because Charniodiscus spinosus and Arborea sp. A differ not only in the presence/absence of tentacle-like structures in their holdfasts (see discussion below) but also in the ratio of frond length to stem length, we are hesitant to consider these two species synonymous.

The tentacle-bearing basal disc of Arborea sp. A is morphologically indistinguishable from the discoidal fossil Hiemalora, which also occurs in the Shibantan assemblage (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhou, Xiao, Wang, Guan, Hua and Yuan2014; Shao et al., Reference Shao, Chen, Zhou and Yuan2019). The Shibantan Arborea sp. A specimen provides clear evidence that an arboreomorph frond can have a Hiemalora-type holdfast. Two specimens of Charniodiscus from Newfoundland are also associated with a few filamentous structures (Liu and Dunn, Reference Liu and Dunn2020). The frondose fossil Primocandelabrum from the Bonavista Peninsula, Canada, possesses either a Hiemalora-type or an Aspidella-type holdfast (i.e., discoidal structure without radiating tentacle-like appendages). Hofmann et al. (Reference Hofmann, O'Brien and King2008) considered the presence/absence of tentacle-like structures as the main diagnostic characteristic to distinguish Primocandelabrum hiemaloranum Hofmann, O'Brien, and King, Reference Hofmann, O'Brien and King2008 and Primocandelabrum sp. They also commented that these two species are strikingly similar in frond morphologies but differ only in holdfast structures. The presence/absence of tentacle-like structures could reflect genuine biological features or taphomorphs because the tentacle-like appendages might not manifest on the bedding surface if they are preserved in the sediment and unexposed on the bedding surface. If Hiemalora-type and Aspidella-type basal discs are different taphomorphs of the same biological structure, as Burzynski and Narbonne (Reference Burzynski and Narbonne2015) suggested, it might not be appropriate to use the presence/absence of tentacle-like structures in holdfasts as a diagnostic feature for taxonomic distinction. For this reason and because there is only one specimen in our collection, we leave Arborea sp. A in open nomenclature.

Arborea sp. B

Figure 6.5, 6.6

Occurrence

Shibantan Member, Dengying Formation, Yangtze Gorges area of South China.

Description

The only specimen (Fig. 6.5) is 15.3 cm in length (measured from the center of the basal disc to the apex of the petalodium), 1.5 cm in width, and occurs as a positive hyporelief, consisting of a basal disc, a petalodium, and a connecting stem. The petalodium is elongate and nearly parallel-sided. The uppermost part of the petalodium is poorly preserved, and the remaining petalodium is 11.7 cm long and contains 34 primary branches on either side of the stalk. The primary branches diverge at 30–45°. No central stalk is present, but there is a central furrow in the lower part of the petalodium. No discernible secondary branches are observed. The basal disc is 3.5 cm in diameter with a faint outline. The basal disc is largely smooth, with a central boss aligned with the stem. The basal disc is attached with a ring of closely arranged tentacle-like structures up to 0.8 cm in length. The stem is 3.6 cm long and appears to have a central furrow flanked by two lateral ridges.

Materials

One specimen.

Remarks

The overall shape of Arborea sp. B resembles that of Arborea arborea, but it has a greater number of primary branches. Also, the petalodium of Arborea sp. B is elongated and parallel-sided, different from the ovate petalodium of Arborea arborea. Arborea sp. B also bears a large Hiemalora-like basal disc. As discussed above, because the morphology of basal discs is susceptible to preservational variation (Hofmann et al., Reference Hofmann, O'Brien and King2008; Dunn et al., Reference Dunn, Liu and Gehling2019a), the only specimen of Arborea sp. B is placed in open nomenclature.

Taphonomy

Ediacara-type fossils have been found in a wide range of taphonomic windows, mostly in sandstones (Sprigg, Reference Sprigg1947), siltstones (Grazhdankin, Reference Grazhdankin2004), beneath volcanic tuffs (Narbonne, Reference Narbonne2005), and less commonly in carbonaceous shales (Grazhdankin et al., Reference Grazhdankin, Balthasar, Nagovitsin and Kochnev2008; Tang et al., Reference Tang, Yin, Bengtson, Liu, Wang and Gao2008; Zhu et al., Reference Zhu, Gehling, Xiao, Zhao and Droser2008; Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Droser, Gehling, Hughes, Wan, Chen and Yuan2013) and carbonates (Sun, Reference Sun1986; Grazhdankin et al., Reference Grazhdankin, Balthasar, Nagovitsin and Kochnev2008; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhou, Xiao, Wang, Guan, Hua and Yuan2014). The Shibantan Member in South China and the Khatyspyt Formation in Arctic Siberia represent the only two carbonate successions that are known to host morphologically complex, soft-bodied Ediacara-type macrofossils (Duda et al., Reference Duda, Zhu and Reitner2016), although dolostone of the Gametrail Formation in northwestern Canada also contains some simple discoidal Ediacara-type macrofossils (MacNaughton et al., Reference MacNaughton, Narbonne and Dalrymple2000). The Shibantan limestone hosts a moderately diverse assemblage of Ediacaran fossils, including Pteridinium, Hiemalora, Rangea, and now Arborea, as well as the tubular fossil Wutubus Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhou, Xiao, Wang, Guan, Hua and Yuan2014, the segmented and trilobate animal Yilingia Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhou, Yuan and Xiao2019, and abundant trace fossils (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhou, Meyer, Xiang, Schiffbauer, Yuan and Xiao2013, Reference Chen, Chen, Zhou, Yuan and Xiao2018, Reference Chen, Zhou, Yuan and Xiao2019; Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Xiao, Gill, Schiffbauer, Chen, Zhou and Yuan2014; Xiao et al., Reference Xiao, Chen, Zhou and Yuan2019).

Arborea from the late Ediacaran Shibantan limestone of South China are preserved as impressions and casts/molds. On bed tops, petaloids tend to be preserved as negative reliefs, whereas stalks and holdfasts are preserved as positive reliefs. A transverse thin section of an epirelief specimen of Arborea arborea cut perpendicular to the bedding plane illustrates this style of preservation (Fig. 7.1–7.5). The difference in relief between the stalk/holdfast and the petaloids likely reflects a combination of biological and taphonomic features: the holdfast was buried in sediment (and perhaps filled with sediment) in life, the stem and stalk might have had a greater structural integrity than the petalodium, and the petalodium might have been inflated in life and made concave impressions when it fell upon microbial mats (Fig. 7.6). Upon burial, a thin veneer of authigenic calcite was formed along the buried microbial mats, replicating the morphology of whichever side of the petalodium contacted the microbial mats (Fig. 7.7). The buried petalodium subsequently decomposed and collapsed, with sediment filling from above (Fig. 7.8).

Figure 7. Petrographic observations and proposed preservation mechanism of Arborea: (1) specimen of Arborea arborea preserved on bed top; (2) transverse section cut perpendicular to bedding plane along red line in (1), in plane-polarized light, showing the central stalk and primary branches (arrows); stratigraphic up direction at top; (3–5) magnified views of labeled dots in (2): (3) possible lithified microbial mat (arrow) on fossil surface, with abundant clotted organic matter; (4, 5) calcite crystals (arrows) surrounded by organic matter interpreted to represent microbial mats underlying fossil surface; note abundant organic inclusions in calcite crystals; (6–8) schematic illustrations showing a proposed model of Arborea preservation: (6) transverse sectional view of Arborea before burial (blue = seawater; green = microbial mat; gray = sediment); (7) early stage of burial, with a carbonate veneer formed rapidly along the former microbial mat surface (red curve), which replicated the morphology of Arborea in contact with mat surface; (8) organism collapsed due to decomposition and compaction, with its lower surface (side in contact with microbial mat) preserved as a positive hyporelief. Scale bars = 5 mm (1); 1 mm (2); 20 μm (3–5).

Early diagenetic cementation to stabilize the morphology of buried carcasses prior to significant degradation is essential for the preservation of Ediacara-type macrofossils. In siliciclastic environments, this is likely achieved by the precipitation of sulfide minerals in the microbial mat that covers the buried carcasses (Gehling, Reference Gehling1999; Liu, Reference Liu2016; Liu et al., Reference Liu, McMahon, Matthews, Still and Brasier2019), thus forming ‘death masks’ of Ediacara-type organisms (Gehling, Reference Gehling1999). The ubiquitous microbial mats in Ediacaran benthic marine realms provided favorable loci for precipitation of iron monosulfides, fueled by microbial sulfate and iron reduction during organic degradation. These metastable iron monosulfides were transformed to pyrites during early diagenesis and molded the external features of Ediacara-type organisms. Alternatively, Tarhan et al. (Reference Tarhan, Hood, Droser, Gehling and Briggs2016) proposed that early diagenetic precipitation of silica, which was ultimately sourced from seawater due to the high silica content in Ediacaran oceans, might have facilitated the preservation of soft-bodied macroscopic fossils. Thin-section observations of Shibantan Arborea specimens show that calcite, rather than pyrite or silica, is associated with the fossils (Fig. 7), suggesting that authigenic calcite might have played an important taphonomic role here. Indeed, Bykova et al. (Reference Bykova, Gill, Grazhdankin, Rogov and Xiao2017) independently suggested that early authigenic calcite cementation, partly facilitated by masking microbial mats, might have fulfilled the role of casting and molding the morphologies of Ediacara-type fossils, e.g., Aspidella Billings, Reference Billings1872, preserved in carbonate facies of the Khatyspyt Formation in Arctic Siberia.

Like the Khatyspyt specimens, traces of microbial mats as evidenced by dark organic laminae are often associated with the fossil surface of Arborea preserved in the Shibantan limestone (Fig. 7.2, 7.3). Within the putative microbial mats, organic matter forms clots and anastomosing stringers around carbonate minerals, which are also cloudy and full of organic inclusions, typical of authigenic minerals precipitated in degrading microbial mats (Flügel, Reference Flügel2010; Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhou, Meyer, Xiang, Schiffbauer, Yuan and Xiao2013, Reference Chen, Zhou, Xiao, Wang, Guan, Hua and Yuan2014; Meyer et al., Reference Meyer, Xiao, Gill, Schiffbauer, Chen, Zhou and Yuan2014). In modern microbial mats, cyanobacteria and other microbes produce exopolymeric substances (EPS), which inhibit precipitation of calcium carbonate by absorbing Ca2+ (e.g., Dupraz and Visscher, Reference Dupraz and Visscher2005; Glunk et al., Reference Glunk, Dupraz, Braissant, Gallagher, Verrecchia and Visscher2011; Pace et al., Reference Pace, Bourillot, Bouton, Vennin, Braissant, Dupraz, Duteil, Bundeleva, Patrier, Galaup, Yokoyama, Franceschi, Virgone and Visscher2018). Immediately beneath the cyanobacterial mat, a large amount of calcium carbonate precipitation initiates where degradation of EPS occurs. Low-molecular-weight organic carbon as well as EPS are broken down by sulfate-reducing microbes, liberating Ca2+ and increasing alkalinity. The zone of microbial sulfate reduction, which could be very shallow and only 2–5 mm deep from the mat surface (e.g., Visscher et al., Reference Visscher, Reid and Bebout2000; Glunk et al., Reference Glunk, Dupraz, Braissant, Gallagher, Verrecchia and Visscher2011), is where carbonate precipitation occurs. A similar carbonate precipitation mechanism may have also played an important role in stabilizing the mat surfaces, hence facilitating the preservation of Arborea fossils in the Shibantan limestone.

Sun (Reference Sun1986) noted that the Ediacaran fossil Paracharnia Sun, Reference Sun1986 from the Shibantan Member is closely associated with vendotaenid macroalgal remains. Abundant vendotaenids are also present on the slab of the holotype of Arborea denticulata n. sp. and some of them are directly associated with specimens of Arborea denticulata n. sp. (Fig 4.3). Intriguingly, vendotaenids are typically preserved as carbonaceous films perhaps surrounded by authigenic minerals, e.g., clays and pyrites (Anderson et al., Reference Anderson, Schiffbauer and Xiao2011), whereas Arborea denticulata n. sp. is preserved as casts and molds. The co-existence of two different types of preservation in the same slab is intriguing. We speculate that biological, ecological, and stratinomic differences could have led to different preservation modes in vendotaenids and Arborea denticulata n. sp. For example, vendotaenids are traditionally interpreted as thin planktonic thalli that are unlikely to make concave impressions on sediment surface, whereas Arborea denticulata n. sp. was a benthic macro-organism with a three dimensionality that allowed cast-and-mold preservation. Additionally, different tissue types between vendotaenids (possibly algae) and Arborea denticulata n. sp. (probably a total-group metazoan) might have also contributed to their different preservational modes.

Conclusion

This report augments our knowledge about Ediacaran frondose fossils by illustrating four taxa of Arborea (Arborea arborea, Arborea denticulata n. sp., Arborea sp. A, and Arborea sp. B) from the terminal Ediacaran Shibantan limestone in the Yangtze Gorges area of South China. Arborea arborea is the most abundant among the four taxa. Arborea denticulata n. sp. resembles Arborea arborea in general morphology but differs in possessing fewer primary branches that are rectangular in shape, as well as a lower length/width ratio of its primary branches. Arborea sp. A and Arborea sp. B are fronds with a Hiemalora-type basal attachment.

Microbial mats and early diagenetic precipitation of carbonate minerals might have facilitated the preservation of Arborea in the Shibantan limestone. The co-existence of Ediacaran fronds (preserved as casts and molds) and vendotaenids (preserved as carbonaceous films, perhaps surrounded by authigenic minerals) testifies the taphonomic diversity in the Shibantan Member.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Chinese Academy of Sciences (QYZDJ-SSW-DQC009, XDB26000000, and XDB18000000), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41921002 and 41602007), the Chinese Ministry of Science and Technology (2017YFC0603100), the Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province of China (BK20161090), and the State Key Laboratory of Palaeobiology and Stratigraphy (20201102). SX was supported by the U.S. National Science Foundation (EAR-2021207). The paper has benefitted from discussions with Y. Shao. Figure 5 was drawn by Y. Du. We thank Associate Editor A. Liu, G. Narbonne, and M. Laflamme for constructive reviews.