Introduction

Since Shelby County v. Holder (2013), which undercut key enforcement provisions of the Voting Rights Act, minority voters have faced increased barriers to accessing the vote in states across the country (Barreto et al., Reference Barreto, Nuño, Sanchez and Walker2019; Fraga and Miller, Reference Fraga and MillerForthcoming; Walker et al., Reference Walker, Herron and Smith2019). Native Americans are no exception in states where they comprise a substantial portion of the population and are potentially decisive to election outcomes. In the few years leading up to the 2020 election, voting rights advocates have challenged election rules in several states on the grounds that they are likely to disproportionately impact Native American voters. Two months before the election, the courts in Montana struck down provisions that restricted how ballots could be collected for the disproportionate burden such provisions would present for Native American people living on remote reservations (Court permenantly strikes down Montana law that restricts voting rights of Native Americans, 2020). Advocates have likewise challenged election rules in Nevada, which moved to only vote-by-mail in response to the Novel Coronavirus Pandemic, but which again threatens Native Americans' capacity to vote, since many people living on reservations do not receive residential mail delivery (Nevada tribes seek to protect Native voters, 2020).

Perhaps most notably, North Dakota instituted a voter identification requirement that seemed targeted to Native American residents, insofar as it required one's ID to list a physical address, which many living on reservations do not possess. North Dakota's residential address requirement recalls those employed by states to disenfranchise Native Americans under Jim Crow, which for a variety of reasons very often turned on whether one lived on a reservation (described in detail below). Yet, even as election administration rules intersect with residency and geography in ways that increase barriers to voting for this group, little empirical evidence exists around how such laws systematically impact Native Americans. This paper addresses this gap in the literature. We draw on two unique surveys of eligible Native American voters in North Dakota that measure access to a valid piece of identification under the state's law. While our analysis is limited to one specific state, the richness of our data allow us to draw out how election administration may impact Native American voters when those rules intersect with the specific nature of Native American residency and the political geography of living on a reservation. Our analysis thus offers insight into the ongoing contest around voting rights for this group across multiple contexts.

Over 30 states have laws requiring identification to vote (Underhill, Reference Underhill2019). Since the Supreme Court ruled that such laws do not violate the Voting Rights Act legal challenges have shifted to the states, yielding inconsistent outcomes (Barreto et al., Reference Barreto, Nuño, Sanchez and Walker2019). Legislators craft laws specific to state context, and North Dakota is a key example. At 5% of the population, Native Americans are the state's largest minority group (Statistics, 2019). Prior to 2013, the state employed a non-strict identification requirement that allowed vouchers and affidavits as failsafe measures (Campbell and De Leon, Reference Campbell and De Leon2020). Following Democrat Heidi Heitkamp's successful senate campaign, to which Native Americans were crucial, lawmakers passed a strict version eliminating the failsafe measures (Reilly, Reference Reilly2018). Acceptable identification must include one's name, date of birth and current residential address (Campbell and De Leon, Reference Campbell and De Leon2020). While tribal identification is accepted, such IDs often list a mailing address instead of a residential one (Campbell and De Leon, Reference Campbell and De Leon2020). Over half the Native population resides on a reservation (Statistics, 2019), which are so remote they are not provided residential delivery by the postal service. Instead, individuals receive mail at a post office box, and it is this address that is printed on tribal IDs (Campbell and De Leon, Reference Campbell and De Leon2020). While advocates successfully challenged the law in 2015, the amended version preserved the residential address requirement, and it was again challenged in 2017 (Campbell and De Leon, Reference Campbell and De Leon2020).

Lawsuits challenging North Dakota's law draw on survey data examining access to an ID among Native and non-Native residents, but more rigorous analyses than a simple comparison of the haves and have-nots is lacking. Moreover, existing scholarship overlooks the extent to which such laws are tailored to the populations in the states that adopt them. North Dakota's residential address requirement recalls those employed by states to disenfranchise Native Americans under Jim Crow. As states with large Native populations, like Nevada, Arizona, Texas, and Florida, become important to national elections, and their minority populations to local ones, it behooves scholars to understand the means by which otherwise seemingly innocuous policies disproportionately inhibit access to the vote. To that end, we employ two unique surveys to detail the impacts of the voter identification laws on Native voters in North Dakota. We ask: Do Native Americans in North Dakota possess a valid identification at rates similar to their white counterparts, or like minorities in other states are they less likely to possess such an ID? Does any observed relationship between race and possession of a valid ID persist after accounting for socio-economic status? What are the specific obstacles to voting faced by this population?

In what follows, we begin by detailing the historical disenfranchisement of Native Americans. We then review the specific context in North Dakota, drawing out how we might expect such laws to negatively impact Native voters. We then detail our data and methods, before turning to an explanation of our findings. We find that Native Americans are seven percentage points less likely to possess a valid piece of identification than are whites, a gap that replicates across both datasets and remains statistically meaningful after including relevant covariates. Among those without an ID, Native Americans are significantly less likely to possess the necessary documents to obtain an ID. Finally, Native Americans are more likely to report that they would face significant barriers to getting an ID. We bring needed attention to the impact of carefully crafted electoral rules on this often-overlooked group.

Relevant literature

The historical disenfranchisement of Native American voters

Historically, Native Americans have faced institutional barriers to voting that centered around their status as members of sovereign nations and without formal citizenship. At the turn of the 20th century when federal policy focused largely on assimilating the Native population, tribal members could gain citizenship and the right to vote through demonstrably cutting all ties with their tribe and traditional ways of life (Wolfley, Reference Wolfley1991). Subsequent to the passage of the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924, which granted Native Americans formal citizenship, institutional barriers to voting stemmed from the threat they posed to the dominant racial order in states where they comprised a large enough portion of a given electorate to sway election outcomes (Ferguson-Bohnee, Reference Ferguson-Bohnee2015). States employed Jim-Crow style tactics to deny Native Americans the right to vote. In some places officials argued that tribal sovereignty precluded participation in state and local government, even as citizenship permitted voting in federal elections; drawing on similar logic, administrators in Arizona employed competency requirements, where they argued that residents of reservations were technically dependents of the federal government, and thus not fit to cast a ballot (Ferguson-Bohnee, Reference Ferguson-Bohnee2015). In New Mexico, Native Americans were summarily barred from voting, despite gaining citizenship, until 1948 (Ferguson-Bohnee, Reference Ferguson-Bohnee2015; Kickingwoman, Reference Kickingwoman2020). Access to the ballot was won when Miguel Trujillo, a World War II Marine veteran from the Pueblo of Isleta, used litigation to extend the right to vote for all Native American people in the state (Kickingwoman, Reference Kickingwoman2020).

Especially pernicious were residency requirements and literacy tests. States like Utah leveraged residency requirements to exclude Native Americans, delineating in-state residency along reservation lines, and in some cases arguing that tribal citizenship precluded state citizenship (Wolfley, Reference Wolfley1991; McDonald, Reference McDonald2004). Literacy tests likewise disproportionately impacted Native Americans, a substantial portion of whom were not English literate (Wolfley, Reference Wolfley1991). Literacy requirements in particular led to special coverage under the Voting Rights Act, extended to protect language minorities in 1975, where substantial evidence supported that Native Americans had routinely had their rights curtailed (McDonald, Reference McDonald2004; Schroedel and Aslanian, Reference Schroedel and Aslanian2015). Between 1970 and 1975 alone the Department of Justice was involved in over 30 lawsuits regarding the disenfranchisement of this group (McDonald, Reference McDonald2004; Schroedel and Aslanian, Reference Schroedel and Aslanian2015). In the wake of the 1975 extension, efforts to diminish the electoral power of Native Americans again mirrored those directed toward other minority groups, centering on vote dilution through districting, election and nomination schemes that prevented them from electing their candidates of choice (Wolfley, Reference Wolfley1991; McDonald, Reference McDonald2004; Wang Reference Wang2012; Pryor et al., Reference Pryor, Herrick and Davis2019).

The history of the suppression of Native American votes provides insight into how more recent changes to election administration, like voter identification laws, might disproportionately impact Native American voters. Requirements that one's ID carry a physical address beyond proof of residency on a reservation within a given state establish extra barriers related to reservation dwelling, reminiscent of these Jim Crow era laws. The historical institutional context around voting restrictions suggests that to the extent that changes to election administration condition access to the ballot box on residency in ways that uniquely intersect with tribal affiliation in particular, we should expect disproportionate outcomes for Native American voters. This is true above and beyond the sorts of barriers introduced by the low socio-economic status that Native Americans may likewise face, but which changes related to residency may exacerbate. For example, reducing the number of polling locations available at which to cast ballots may be expected to disparately negatively impact Native Americans living on reservations insofar as they may have to travel further to vote. Thus, in assessing how identification requirements might negatively impact Native Americans, we center the challenges posed by residing on a reservation.

The impact of voter identification laws on Native Americans

As a consequence of this long history with institutional discrimination, researchers find that Native Americans vote at exceptionally low rates, even relative to other minority groups (Peterson, Reference Peterson1997; Huyser et al., Reference Huyser, Sanchez and Vargas2017). Yet, the turnout gap is narrowing and Native Americans participate at higher rates in other types of activities, suggesting that low voter turnout is not due to efficacy or interest (Skopek and Garner, Reference Skopek and Garner2014; Huyser et al., Reference Huyser, Sanchez and Vargas2017; Herrick and Mendez, Reference Herrick and Mendez2019). At the same time, data limitations inhibit our knowledge around Native American political attitudes and behavior. Surveys standard in the discipline of Political Science, like the American National Election Survey and the General Social Survey, include too few Native American respondents to generate reliable analyses. Thus, little systematic evidence around the impact of voter identification laws on Native American populations exist. We therefore turn to research on the impact of voter identification laws on other non-white groups, together with what we know about the historical exclusion of Native Americans specifically, to develop a theoretical foundation for the analysis that follows.

Research around the impact of voter identification laws on turnout is mixed (Erikson and Minnite, Reference Erikson and Minnite2009; Hershey, Reference Hershey2009). Several studies conclude that the impact of voter ID laws on turnout is negligible (Erikson and Minnite, Reference Erikson and Minnite2009; Mycoff et al., Reference Mycoff, Wagner and Wilson2009; Grimmer et al., Reference Grimmer, Hersh, Meredith, Mummolo and Nall2018; Cantoni and Pons, Reference Cantoni and Pons2021). Others find that the strictest laws have a depressive effect, but do not find differences among racial and ethnic groups (Hood and Bullock, Reference Hood and Bullock2012; Hood and Buchanan, Reference Hood and Buchanan2020). In keeping with this, using an opt-in survey of Native Americans, Herrick and Mendez (Reference Herrick and Mendez2019) find that voter ID laws and court cases related to American Indian voting rights have no effect on the participation of Native Americans. In contrast, a handful of studies demonstrate the negative consequences of identification laws for voting among Black Americans and Latinos (Vercellotti and Anderson, Reference Vercellotti and Anderson2006; Hajnal et al., Reference Hajnal, Lajevardi and Nielson2017; Kuk et al., Reference Kuk, Hajnal and Lajevardi2020; Fraga and Miller, Reference Fraga and MillerForthcoming; Grimmer and Yoder, Reference Grimmer and Yoder2021). For example, Hajnal et al. (Reference Hajnal, Lajevardi and Nielson2017), use validated vote data from the Cooperative Congressional Election Study to examine turnout across states and elections, and find diminished turnout among Latino and Black Americans in states with the strictest laws. In what is perhaps the first direct test, Fraga and Miller (Reference Fraga and MillerForthcoming) link voter files in Texas with records of individuals who cast a provisional ballot when unable to present an ID at the polls, and report that, “Black voters were approximately 54% more likely to vote without identification than non-hispanic whites, while Latinx voters were 14% more likely to do so than non-hispanic whites,” (pg. 17). Using administrative records from North Carolina and exploiting changes in the ID law in 2016, Grimmer and Yoder (Reference Grimmer and Yoder2021) find that the law deterred turnout among those without ID, and that non-white voters were less likely to possess an ID than were white voters. In keeping with this, Henninger et al. (Reference Henninger, Meredith and Morse2021) found that minority voters in Michigan who ostensibly had ID as verified by administrative records were five times more likely to fail to produce that ID at the polls than were white voters.

These studies are laudable for their precise empirical approach to evaluating the extant effects of voter identification laws. However, they are focused on turnout, evaluating access to a valid piece of identification among individuals who are already registered to vote. An exclusive focus on how such laws may impact individuals already registered to vote or with a voting history obscures the full extent of the harm incurred by laws apparently structured to disenfranchise minority voters. Assessments of these laws should include an account of the real barriers they erect for all eligible voters. One does not lose the right to vote simply because one is unlikely to use it, and the importance of access to the franchise to the health of American democracy should remain at the center of our inquiry if we are interested in evaluating power. Moreover, administrative records do not permit an analysis of the unique barriers ID laws present to members of hard to reach populations for the same reasons that they are hard to reach: such individuals may live on the social margins and in ways that evade capture by government records. This is particularly true in the case of Native Americans who live on reservations, whose residency does not make their claim to the right to vote less valid.

In order to answer the normatively democratic important question of the disparate impact of identification laws, scholars have leveraged surveys that allow them to employ culturally competent methods of reaching minority populations, to ask specific questions specific to a states' law, and around access to relevant resources to obtain a compliant ID. For example, leveraging six datasets collected between 2008 and 2014, Barreto et al. (Reference Barreto, Nuño, Sanchez and Walker2019) find that Blacks and Latinos were almost ten percentage points less likely to have an appropriate ID than were whites. Even given the breadth of their data, however, Barreto et al. (Reference Barreto, Nuño, Sanchez and Walker2019) do not offer insight into how such laws might uniquely impact the Native American population. Recent findings that Black Americans and Latinos are less likely to possess a valid piece of identification together with the specific history of the disenfranchisement of Native Americans suggests that this group is likely to be vulnerable to such laws. As noted above, election rules are likely to disproportionately impact Native Americans when access to the vote is conditioned on residency, wherein tribal affiliation is relevant. The requirement that one shows a piece of ID to vote is not facially problematic, but it may become so depending on the conditions one's ID has to meet. For example, if one must possess an identification issued by the state where tribal identification would not suffice, we would expect Native Americans to be disproportionately impacted by that law. The North Dakota law includes a requirement that one's identification list a physical address. The physical address requirement itself likewise becomes problematic because while tribal ID's are accepted, they often do not include a physical address. As a consequence, the law has been challenged in court.

North Dakota

North Dakota first introduced a voter identification requirement in 2004 pursuant to the Help American Vote Act (HAVA). The initial law required voters to provide a piece of ID at the polls, but allowed a wide variety of types of ID, and individuals had the option to vote by affidavit or for poll workers to vouch for them (Campbell and De Leon, Reference Campbell and De Leon2020). In 2012, the race for North Dakota's open Senate seat was extraordinarily close with Democrat Heidi Heitkamp beating out her Republican opponent by less than 3,000 votes (Nichols, Reference Nichols2018). In the months after her victory, the Republican-dominated legislature began considering proposed changes to their existing voter ID law, eventually passing a strict version in 2013. The 2013 law eliminated fail-safe options including voting by affidavit and with the affirmation of one's identity by a poll worker, and tightened restrictions on the types of ID poll workers may accept (Campbell and De Leon, Reference Campbell and De Leon2020). Under the new law, identification must be unexpired and must include one's name, date of birth, and current physical address.

The requirement that the piece of identification includes a current physical address was understood to potentially disproportionately impact Native Americans, who are less likely to have a piece of identification with a physical address and more likely to possess an ID that contains a P.O. Box (Feldman, Reference Feldman2018). Native Americans were crucial to Heitkamp's victory. The Native American Rights Fund (NARF) challenged the law in 2016, and the courts blocked its implementation without some kind of failsafe measure, in recognition of its potentially disparate impact on Native Americans (Campbell and De Leon, Reference Campbell and De Leon2020). Therefore, in 2017 North Dakota law-makers rewrote the law, this time including the option to fill out a provisional ballot contingent on the presentation of a valid piece of identification within 6 days of the election (Astor, Reference Astor2018). Thus, while the new law addressed the concerns outlined by courts insofar as it ensured no one would be turned away at the polls, it still inhibited voting for those who lacked a piece of ID with a physical address in the first place. The U.S. District Court therefore blocked the enforcement of the 2017 law, issuing an order that allowed identification with P.O. boxes and expanded the types of acceptable identification. The state of North Dakota challenged the district court's ruling, but their request to stay the order during the June primaries was denied by the 8th circuit court of appeals in June of 2018 (Feldman, Reference Feldman2018). In the lead up to the 2018 midterms, the 8th circuit again held a special hearing and this time overturned the circuit court's order, meaning that the law would be in effect during the November election, at which point early voting had already begun in North Dakota. NARF filed an emergency application with the Supreme Court. The Court denied the application on the grounds that they did not want to introduce additional confusion during the election process (Campbell and De Leon, Reference Campbell and De Leon2020).

At 5.6% of the population, Native Americans are the largest minority in North Dakota (Statistics, 2019). The key provision in North Dakota's law that has natural implications for Native Americans is the requirement that one's ID list a physical address. A P.O. Box is considered unacceptable. Over half of the Native American population lives on a reservation (Statistics, 2019). Reservations are remote, so much so that they are not provided residential delivery by the postal service. Moreover, most residences located within the reservation are not assigned an official address, colloquial knowledge standing in for formal mapping and directions. For these reasons, Tribal governments and the Bureau of Indian Affairs print ID cards with a P.O. Box. Thus, the means by which the voter ID law may directly, uniquely and negatively impact Native Americans in North Dakota is straight forward. As a consequence of this potential impact, in February of 2020 North Dakota entered into an agreement with two tribes that makes suitable provision for individuals who may not have a physical address listed on their ID (Campbell and De Leon, Reference Campbell and De Leon2020). Thus, the law both remains in effect while making an exception for potentially impacted Native Americans. The case of North Dakota provides insight into how administrative laws in other states with significant Native American populations may likewise impact those voters.

Voter identification laws may both impact racial minorities directly via tailored clauses like the address requirement in North Dakota's law, but they also do so indirectly via the costs that are associated with accessing a valid piece of government-issued identification. For example, it may be difficult for some eligible voters to access offices where they can get a piece of identification, and researchers estimate that in states with restrictive laws substantial portions of the voting age population live at least 10 miles from an office that issues state IDs. In Mississippi, Wisconsin and Alabama over 30% of the voting-age population resides more than 10 miles away from such an office, and these same states very often have a low investment in public transportation (Gaskins and Iyer, Reference Gaskins and Iyer2012). In the case of North Dakota, law makers appeared to have taken efforts to substantially reduce access to offices providing state-issued IDs. The 2017 version of the law reduced the hours of the driver's license site that is most accessible to the specific tribes named in the suit such that it, “now operates the most restrictive hours of any location; it is open for less than five hours one day a month; there is not a single driver's license site on an in Indian reservation in North Dakota,” (Campbell and De Leon, Reference Campbell and De Leon2020).

The cost of accessing a valid piece of ID further includes those associated with getting the underlying documentation, like a birth certificate or bank statement or utility bill that bears one's address. Native Americans in North Dakota lag behind their non-Native counterparts socio-economically across a variety of indicators. While over 90% of the total population in the state has at least a high school diploma, this decreases to 79% of Native Americans (The American Community Survey, 2019). Almost 40% of Native Americans live below the poverty line, compared to about 10% of the overall population (The American Community Survey, 2019). They are likewise less likely to have full employment, to have access to health insurance and to have achieved a college degree than are non-Natives living in North Dakota (The American Community Survey, 2019).

One aspect of identification laws that has been lost in the scholarly shuffle around the impact of these laws on turnout is the extent to which identification laws are tailored to the populations in the states that pass them. Identification laws are not created equal, but instead employ unique clauses and caveats that impact the marginalized in unique ways. North Dakota's law now includes appropriate protections for Native American voters, but those protections were won because of a lengthy and costly court battle waged by voting rights activists that spanned multiple election cycles. As states with large indigenous populations become increasingly important to national elections, and these same voters to local ones, it behooves scholars to understand the means by which otherwise seemingly innocuous policies and procedures disproportionately inhibit or support access to the ballot box. To that end, we now turn to unique survey data to detail the potential impacts of the voter ID law on Native and non-Native voters in North Dakota.

Data and methods

This project assesses access to a valid piece of voter identification under North Dakota's law among Native and non-Native Americans in the state. In order to do this, we draw on two original surveys, one collected in 2015, reflecting the specifications of the 2013 law; and one in 2017, after the 2017 amendment which allowed individuals to cast a provisional ballot. The chief alternative approach to measuring rates of possession of a valid ID leverages large, administrative databases collected by relevant public entities, such as the department of motor vehicles (DMV). However, this approach faces a number of challenges. Not all acceptable types of identification may be included in administrative records of this sort, and such records do not account for factors like whether one has lost their ID, had it stolen, changed their name due to marriage, and so forth (DeCrescenzo and Mayer, Reference DeCrescenzo and Mayer2019). Reliance on administrative datasets, moreover, preclude the opportunity to evaluate whether any observed differences persist after controlling for relevant socio-economic factors and the specific obstacles one might experience in an effort to obtain an ID. In order to overcome these challenges, researchers have leveraged survey methods, which allows one to ask individuals directly about the specific nature of their identification in ways tailored to the laws in a given state, and about various other challenges that might arise from having lost one's ID, and confusion around the exact nature of a given law (Barreto et al., Reference Barreto, Nuño, Sanchez and Walker2019; DeCrescenzo and Mayer, Reference DeCrescenzo and Mayer2019).

Surveys are not without their own limitations, and chief among them are challenges related to generating a representative sample of the population of interest. These challenges are particularly acute with respect to hard-to-reach groups. Native Americans are considered hard to reach via traditional survey methods due to the fact that they are numerically small, geographically dispersed, more likely to lack telephones relative to other populations, and language and cultural barriers decrease trust in the interviewer and the surveying organization (Lavelle et al., Reference Lavelle, Larsen and Gundersen2009). Thus, multiple modes of contact, including mail, is the best strategy for collecting data that accurately represent the population (De Leeuw, Reference De Leeuw2005; Dillman et al., Reference Dillman, Lesser, Mason, Carlson, Willits, Robertson and Burke2007). A multi-mode approach can also help mitigate other limitations of surveys, including response and sampling bias (Fowler et al., Reference Fowler, Roman and Di1998; Chang and Krosnick, Reference Chang and Krosnick2009; Rao et al., Reference Rao, Kaminska and McCutcheon2010; Sakshaug et al., Reference Sakshaug, Yan and Tourangeau2010; Ansolabehere and Schaffner, Reference Ansolabehere and Schaffner2011; Atkeson et al., Reference Atkeson, Adams and Michael Alvarez2014). This is the strategy developed by the U.S. Census Bureau in an effort to mitigate undercounting the population, and is thus the most rigorous means of sampling Native Americans available to researchers (Hatcher, Reference Hatcher2002; Lavelle et al., Reference Lavelle, Larsen and Gundersen2009).

Thus, we followed best practices and composed a sampling frame from lists of landline and cellphone numbers, as well as an addressed-based list administered via the mail. The telephone portion of our list came from a combination of random digit dial landline and cell phone sample for the entire state of North Dakota, and a targeted phone sample for Native Americans. For the mail portion, we relied on a combination of randomly selected home addresses and randomly selected Post Office boxes for the state. To ensure that we were reaching a representative sample of Native Americans, we further received a member enrollment roster from each of the major tribes in North Dakota and selected a random sample to contact via mail, after removing individuals already present in the mail/phone sampling frame. Finally, to encourage participation individuals contacted via the mail received multiple follow-up contacts including a letter from tribal leaders, which was intended to increase compliance by heightening trust in the researchers and a sense of importance around participating.

The resulting sample reflects the very deep socioeconomic disparities between Native and non-Natives in the state. For example, according to data from the 2016 American Community Survey, the median income among for whites was $61,387 compared to $33,122 for the American Indian population.Footnote 1 In the 2015 survey, the Native American sample had a mean income between $30,000 and $40,000 annually, relative to non-Natives who had a mean income between $50,000 and $60,000 annually. Our strategy yielded a slightly more educated sample than the statewide population, where 29% of whites in the state hold a college degree compared to 16% of Native Americans.Footnote 2 Comparatively, in our 2015 sample 32% of Non-Native respondents and 25% of Native respondents held a college degree. To correct for these discrepancies, the samples were weighted on age, education, gender, income and reservation dwelling to bring them in line with census estimates.

The final samples included 456 Native American and 875 non-Native respondents in the 2015 survey, and 434 Native American and 869 non-Native respondents in the 2017 survey. Because the method of contacting folks by mail was developed specifically to bolster the hard-to-reach Native American population, nearly all non-Native respondents in both waves completed the survey via phone (97% in 2015, and 98% in 2017). In contrast, 64% of Native American respondents in 2015 and 48% in 2017 completed the survey by mail.Footnote 3 In addition to large sub-samples of Native American voters, the primary analytic value in repeated cross-sections is replication and (dis)confirmation (rather than allowing, for example, an assessment of change over time, which our data are unable to address). The majority of non-Native respondents in both surveys are white. In the 2015 survey, only 88 respondents identified as non-white and non-Native, and in 2017 this was true for only 61 respondents. This reflects North Dakota's overall population, which is 87% white (The American Community Survey, 2019).

Both surveys were designed to evaluate the extent to which voters in North Dakota have access to the sort of identification required to vote under the state's law. Thus, questions were tailored to the law's specifications. For example, respondents were asked to indicate whether they were in possession of any of the accepted forms of identification: a North Dakota driver's license, a North Dakota non-driver identification card that was issued by the North Dakota Department of Transportation, a tribal government-issued identification card or one issued by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, or a long-term care identification certificate issued by a North Dakota facility. Respondents were then asked to indicate whether they had their ID, or whether it had been lost, stolen or revoked, and those who indicated they had their ID were prompted to take it out and look at it to answer questions that followed. Respondents were asked to confirm whether their ID included an address, that the address was a physical address (rather than a P.O. Box), and that it was current.Footnote 4

The law included additional provisions that the ID carry one's date of birth and that it be unexpired. However, the provision of the law thought to disproportionately impact Native Americans concerned whether one's ID listed a current, physical (residential) address. Therefore, individuals who affirmed that they possessed an accepted piece of identification that listed a current, physical address were coded as having an acceptable ID; everyone else was coded as not having an acceptable ID.Footnote 5 In the 2015 survey dataset, 12% of respondents indicated that they did not have access to a valid piece of identification, as did 13% of respondents in the 2017 dataset.Footnote 6

In addition to exploring racial differences among those who do not have access to a valid piece of identification, we are further interested in the various obstacles individuals might face should they want to obtain an ID. In both surveys, we therefore followed up and asked respondents whether they had access to the underlying documents required to obtain identification issued by the state of North Dakota. These documents include proof of citizenship, such as a birth certificate, documentation of a name change if circumstances require it; proof of residency; and proof of social security. In the 2015 survey, among the total population who lacked a valid piece of identification, 60% lacked the appropriate underlying documents to obtain one; the same was true for 51% of respondents in the 2017 survey.

In order to evaluate racially disparate rates of access to a valid piece of identification, we proceed in the following way. Leveraging logistic regression analysis, we begin by evaluating bivariate rates of possession of a valid ID among Native and non-Native respondents. We then subject these findings to more rigorous analysis, including a variety of relevant covariates. Factors that are likely to impact access to a valid piece of identification include socio-economic status, age and gender; those with low levels of education and income are less likely to have a driver's license, and also more likely to face obstacles obtaining such an ID; women face unique challenges, due to the cultural norm related to changing one's name upon marriage; younger voters are more likely to be transient and to not have an updated address; and the elderly are more likely to have expired identification (Barreto et al., Reference Barreto, Nuño, Sanchez and Walker2019). Researchers have likewise found that gender is an important variable to the political incorporation of Native Americans, where men lag behind their female counterparts (Sanchez et al., Reference Sanchez, Foxworth and Evans2020). We then repeat the analysis, but among those without a valid piece of identification, and with respect to barriers to obtaining such identification.

Findings

At the bivariate level, Native Americans are statistically less likely to possess a valid piece of identification than are their white counterparts (p < .01). In the 2015 survey 82% of Native Americans had a valid piece of identification, relative to 89% of white Americans (Figure 1, Table 1). Likewise, in the 2017 survey 81% of Native Americans relative to 88% of whites had an ID acceptable under North Dakota's law. For context, Barreto et al. (Reference Barreto, Nuño, Sanchez and Walker2019) report that in their combined sample, 90.5% of white eligible voters had access to a valid piece of identification, compared with 81.2% of Black eligible voters and 82% of Latino eligible voters. Thus, the findings from North Dakota comport with known estimates derived from similar methods.

Figure 1. Rates of possession of a valid piece of voter identification among Native and Non-Native Americans in North Dakota in 2015 and 2017.

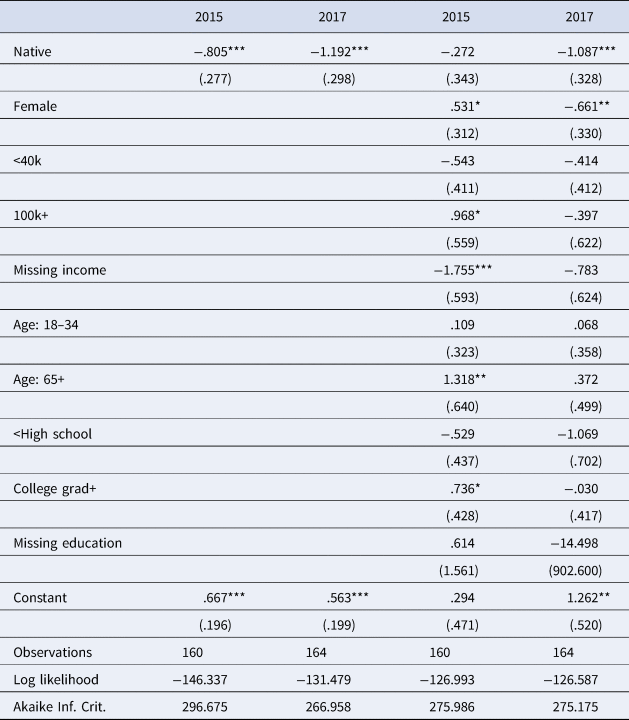

Table 1. Logistic regression results—possession of a valid piece of voter identification by year

Note:*p < .1; **p < .05; ***p < .01.

Although the size of the effect of being Native American on the likelihood of possessing a valid piece of identification diminishes after controlling for a variety of different covariates, the impact of being Native American remains statistically significant (Table 1). Figure 2 displays the average marginal effects of each variable included in the models displayed in Table 1 on the likelihood of possessing a valid piece of identification. Native American status is as important to having access to a piece of identification as is making less than 40k annually in the 2015 dataset and being a young person in the 2017 dataset. We therefore take this as strong evidence that, like Latino and Black Americans in other states, Native Americans are disproportionately burdened by North Dakota's voter identification law. This is particularly striking, given that racial differences persist even after accounting for education and income. Although it is the case that Native Americans are on average poorer than non-Native Americans in North Dakota, material deprivation alone does not account for disparate rates of access to a valid ID. The data allow us to drill down further to examine what percentage of each group lack a valid ID specifically due to the address requirement. Among Native Americans without a valid ID, 20% are due to the address requirement, compared to only 8.2% of non-Native residents for whom the same is true. Like Jim Crow era residency requirements, the unique structure of the law itself and its intersection with the political geography of reservations account for differences in access to a valid piece of identification.

Figure 2. Factors impacting possession of a valid piece of voter identification among Native and Non-Native Americans in North Dakota in 2015 and 2017.

Next, we examine the specific barriers Native Americans face to obtaining a valid piece of identification. We begin by examining access to the underlying documents needed to obtain a government-issued ID. This is particularly relevant because in 2016, North Dakota amended their rules, allowing Native Americans to cast a provisional ballot, assuming they could provide proof of residency within a week of the election. Yet, Native Americans may disproportionately lack these documents for the same reasons that they are less likely to have a valid piece of identification. Table 2 displays rates of possession of the various required documents, including proof of address, to obtain a government-issued piece of identification among survey respondents who did not already have one. Across both surveys, non-Natives are more likely to possess each type of required document, and more likely to possess all three types of required documents. In the 2015 survey, 77% of non-Native respondents who did not already possess a valid piece of identification indicated they could provide some other form of identification, such as a passport or birth certificate, relative to only 62% of Native Americans for who the same was true. Similar differences persisted in the 2017 survey.

Table 2. Percent possessing necessary documents to obtain an ID by race, among those without an ID

Specifically with reference to proof of residence in North Dakota, which would also suffice when paired with an affidavit and an otherwise valid ID, Native Americans are likewise disadvantaged. Such documents might include a utility bill or a financial statement with a North Dakota address listed. In the 2015 survey 81% of non-Natives indicated they had such proof, relative to 71% of Native Americans. In the 2017 survey, the gap is dramatic at over a 30 percentage point difference. We do not make too much of this large gap, however, given that respondents without an appropriate piece of ID are a fairly small portion of our sample overall, and smaller still when split among Native and non-Native respondents. Instead, we examine these trends in order to illustrate that the gap between the two groups persists across nearly all ways of looking at access to an ID and relevant underlying documents.Footnote 7

The specific disadvantage experienced by Native Americans is further demonstrated by rates of use of the affidavit failsafe at the polls in 2016—among those counties with the highest concentrations of Native Americans 5% of ballots cast were via affidavit, while among those counties with the lowest concentration of Native Americans only 2% of votes cast were via affidavit (Barreto and Sanchez, Reference Barreto and Sanchez2017). Moreover, the ID law changed between the 2012 and 2016 elections. Likewise, the use of the affidavit failsafe method increased in high Native American counties by 665%, but declined by 11% in low Native American counties (Barreto and Sanchez, Reference Barreto and Sanchez2017).

Finally, in addition to proof of identification and residency, individuals must provide evidence that they have a social security number. In 2015, 93% of Native and 98% of non-Native American respondents indicated they could provide a social security number. In 2017, 96% of respondents indicated that they could provide proof of a social security number, relative to 83% of Native Americans for whom the same was true. Overall, in 2015 66% of non-Native respondents indicated they had all of the documents required to obtain a government-issued ID, relative to 47% of Native Americans. In 2017, this gap grew to a 30 percentage point difference, where 64% of non-Native respondents indicated they had all required documents relative to 34% of Native American respondents. In both surveys, these bivariate differences are statistically meaningful (Table 3).

Table 3. Logistic regression results—possession of underlying documents necessary to obtain an id by year

Note: *p < .1; **p < .05; ***p < .01.

The 2015 survey afforded the opportunity to explore even further the kinds of barriers individuals may experience when attempting to obtain a government-issued piece of identification that complied with North Dakota's law. Respondents were asked whether a variety of circumstances would pose a problem for getting to the DMV in order to obtain an ID. They included the following: finding out where the nearest DMV office was located; getting a ride to the DMV office; getting time off of school or work to make the trip; accessing public transportation to make the trip; making it to the office during their regular business hours; and making it to their office during regular business hours, specifically during the week. In almost all cases, Native Americans without an ID were more likely to indicate these items would pose a problem for them in trying to obtain an ID (Table 4). Almost 50% of Native Americans indicated taking time off of work or school would be a problem, relative to 29% of non-Native respondents who said so. About 25% of Native Americans likewise indicated it would be a problem to get a ride to the DMV. Fully 67% of Native American respondents without an ID indicated that at least one or more items in the battery posed a problem, relative to 60% of non-Native respondents for whom the same was true. The findings with respect to these kinds of issues that might arise when getting an ID indicate that getting an appropriate ID is not an easy task for those who do not already have one, and in turn highlight the real barrier voter identification laws pose to accessing the vote. These barriers are problematic for all voters, but Native Americans in North Dakota face a disproportionate burden relative to their non-Native counterparts.Footnote 8

Table 4. Percent facing issues getting to the DMV to get an ID, among those without an ID in the 2015 survey

Descriptive findings around access to the DMV provide useful context when thinking through our final research question, which asked what sorts of barriers individuals face when attempting to obtain an ID. Our primary point of inquiry pertains to differences between non-Native and Native American respondents, and we endeavor to rigorously assess these differences by ruling out other explanations, like socio-economic status, and subjecting them to replication. Table 3 displays the results of logistic regression analysis. As mentioned above, at the bivariate level the difference between rates of access to documents required to obtain a government-issued ID are statistically significant.

When subjected to a more rigorous analysis that includes control variables, we find that these differences only achieve significance in the 2017 sample (Table 3). In the 2015 sample, while the impact of being Native American remains negative, the size of the effect is relatively small. These relationships are likewise displayed in Figure 3. Here we can see that in 2015, age, wealth and education have the strongest impact on access to underlying documents required to obtain an ID. In 2017, identifying as Native American was statistically and negatively associated with access to relevant underlying documents among those without an ID, and the size of the effect is commensurate with not having graduated from high school.

Figure 3. Factors impacting possession of the necessary documents to obtain an ID among Native and Non-Native Americans without a valid ID in North Dakota in 2015 and 2017.

We interpret these findings as suggestive that Native Americans lack access to underlying documents necessary to obtain a piece of identification above and beyond issues associated with material deprivation. Together with contextual evidence that Native Americans would face a variety of issues even getting to a DMV, which are likewise associated with the remote nature of living on a reservation, it is clear that the voter identification law in North Dakota poses a significant challenge to accessing the ballot box for this group.

Conclusion

This paper has examined disparate rates of access to a valid piece of identification required to vote among Native and non-Native Americans in North Dakota. We undertake this inquiry because in the wake of court decisions removing important protections for the right to vote for minority populations, attempts at curtailing or diluting minority voting power have proliferated. Scholars elsewhere have paid close attention to the impact of changes to a variety of aspects of election administration on Black and Latino voters. Much less attention as been paid to how election administration may impact Native American voters. At the same time, the importance of the Native American vote to the outcome of federal and local elections is heightened as once reliably red states become purple with changing demographics. Such states include New Mexico, Oklahoma, where at least one house district was competitive in the 2018 midterm election, Arizona, Nevada and Colorado. These states are among the top 15 in terms of size of the Native American population, and New Mexico and Oklahoma are among the top five. Even states like Montana and North Dakota that are not important to presidential outcomes, where election laws have been challenged specifically in reference to Native Americans, take on national importance because they have (or have had) representation from both parties in the national legislature (the contest over which in North Dakota directly preceded a stricter ID law) (Reilly, Reference Reilly2018).

In 2013 North Dakota passed one of the strictest voter identification laws in the country. Although unlike select other states the law does not require one to present an ID with a photo, it does include the requirement that one's ID list a physical address. Native Americans make up the largest minority group in North Dakota, and the physical address requirement has unique implications for this group. A substantial portion of Native Americans live on reservations, which are vast and remote, so much so that the postal service does not provide residential delivery. As such, identification issued by tribal governments often includes a post office box instead of a physical address. While previous scholarly research has examined differential rates of access to a valid ID among whites, Blacks, Latinos and Asian Americans, very little work has examined the consequences of these laws for Native Americans.

Thus, an inquiry into the impact of North Dakota's voter identification law yields important scholarly insight across a variety of dimensions. First, it highlights an oft-overlooked dimension in the literature around voter identification laws—changes to election administration rules designed to deter participation are often tailored to the specific populations of the state. In the case of North Dakota, the law echos residency requirements employed to disenfranchise Native Americans under Jim Crow, insofar as the physical address requirement raises additional burdens for Native Americans that turn on whether one lives on a reservation. Most often research examining the consequences of voter identification laws use one-size-fits-all measures of identification, or examines pre-post turnout at the state level, looking for national consequences. More research is needed around the impact of election administration on important population subgroups, with competency around parochial contexts, and attention to the unique barriers that racial and ethnic marginalization produces for local populations. That is, scholars should not simply query whether an individual has a state-issued ID, but should instead pay attention to how the specific requirements for an acceptable ID map on to the lived experiences of the minoritized populations in a given state. Second, this research offers important insight around Native Americans, about whom we know very little, politically, but who comprise a not-insignificant portion of the population in states where elections are becoming more competitive because of changing demographics.

In order to address these issues, we collected two unique datasets in North Dakota, employing culturally competent survey methods to ensure a representative and robust sample. In addition to a high-quality sample, we also tailored our instrument to the specifics of the law, and asked additional follow up questions about the challenges one might face should they try to obtain an ID. The result is a dataset that is both rich and broad, allowing us to provide detailed contextual information about the barrier to voting North Dakota's law poses for Native Americans, relative to their non-Native counterparts. We find that Native Americans are about seven percentage points less likely to have access to a valid ID than are non-Native respondents, a relationship that is statistically significant, and replicates across both datasets after the inclusion of socio-economic co-variates. They are likewise more likely to lack access to all the documents needed to obtain a piece of government-issued identification.

Our analysis is not without limitations. Despite our best efforts to generate a robust and representative sample of Native Americans in North Dakota, it is modest enough to make subgroup analysis difficult. We do not delineate between those who do and do not live on a reservation; it may be that the impact of these laws are negligible for those who do not live on a reservation. We cannot offer an evaluation of Native Americans by income, gender, or age, all three important factors attenuating the effect of ID laws. Finally, our surveys lack some key measures important to ascertaining the extent effects of election administration procedures, including political factors like interest, attention to news, and past voting behavior (Vercellotti and Anderson, Reference Vercellotti and Anderson2006; Mycoff et al., Reference Mycoff, Wagner and Wilson2009; Barreto et al., Reference Barreto, Nuño, Sanchez and Walker2019). While we center questions of access to an ID, questions about turnout which we are unable to address naturally follow. Issues related to sampling and turnout thus turn attention toward administrative records, of the sort employed by Fraga and Miller (Reference Fraga and MillerForthcoming), Henninger et al. (Reference Henninger, Meredith and Morse2021), and Grimmer and Yoder (Reference Grimmer and Yoder2021). For all these reasons, our intervention is a starting point for thinking about the unique effects of election administration on highly contextualized minoritized populations.

The differences we do observe between Native and non-Native eligible voters in North Dakota are due, in no small part, the requirement that one's ID must include a physical address, which presents a unique challenge for Native Americans, many of whom live in the remoteness of the reservation. North Dakota has at present modified its law to ensure Native Americans without an address on their ID can have their voices heard. This change is a consequence of a lengthy and costly court battle spanning two election cycles. It therefore behooves those concerned with questions of normative democracy to heed the call for continuing research on the specific racial and local nature of election administration raised by this piece, which operate, “within the subtext of racial power to reproduce the inequalities that demand the attention of political scientists in the first place” (Barreto et al., Reference Barreto, Nuño, Sanchez and Walker2019, 3).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/rep.2022.1.

Acknowledgment

The authors would like to thank Matthew Campbell and the Native American Rights Fund for support of this project.