Article contents

Tile-stamps of Philippianus in Late Roman Sicily: a talking signum or evidence for horse-raising?

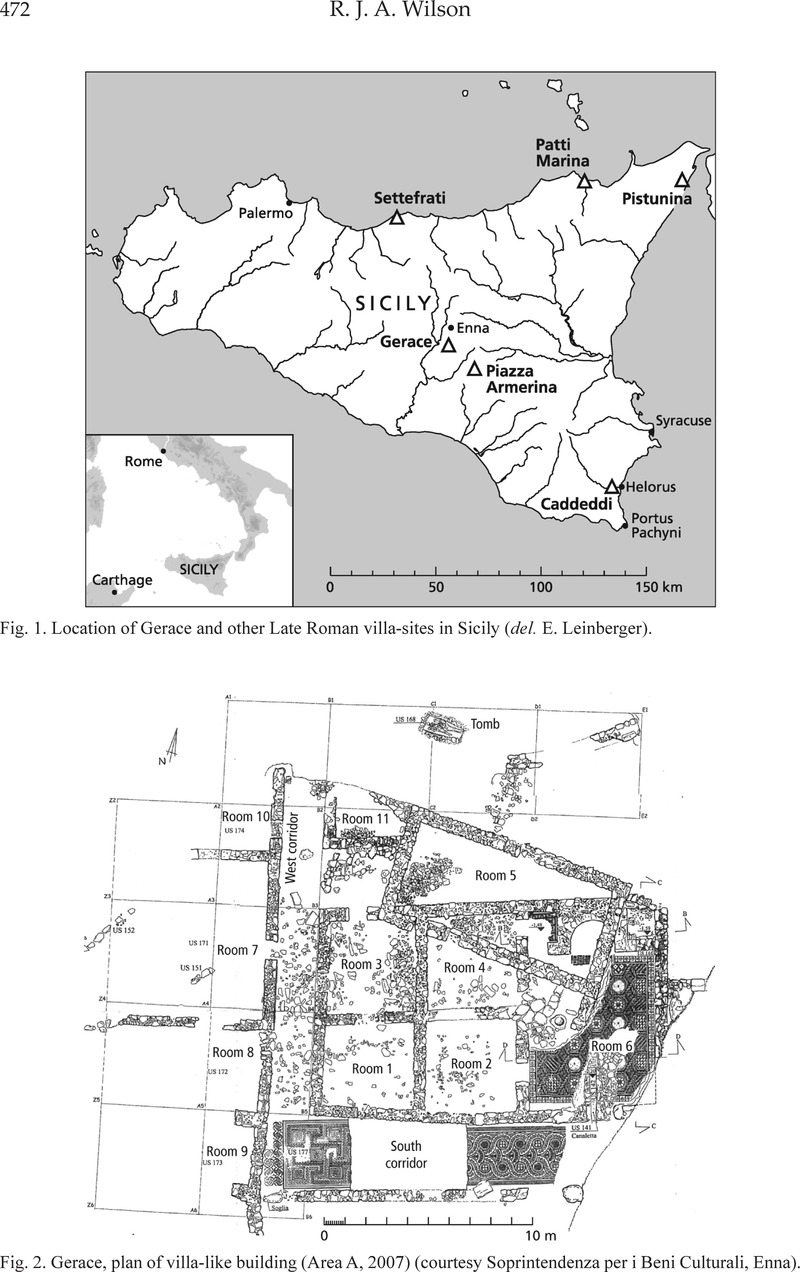

Published online by Cambridge University Press: 27 November 2014

Abstract

- Type

- Archaeological Notes

- Information

- Copyright

- Copyright © Journal of Roman Archaeology L.L.C. 2014

References

1 Platamone, E. Cilia, “Recente scoperta nel territorio di Enna: l’insediamento tardo-romano in contrada Geraci,” L’Africa romana 11.3 (1996) 1683–89Google Scholar; ead., “Rinvenimenti musivi nel territorio di Enna tra passato e presente,” in Bonacasa, R. M. Carra and Guidobaldi, F. (edd.), Atti IV Colloq. Assoc. Ital. Stud. Cons. Mosaico, 1996 (Ravenna 1997) 273–90Google Scholar.

2 Bonanno, C., Carbella, R., Capelli, C. and Piazza, M., “Nuove esplorazioni in località Gerace (Enna-Sicilia),” in Menchelli, S. et al. (edd.), LRCW3 (BAR S2185; Oxford 2010) especially 261 Google Scholar (the pottery reported comprises surface finds, especially from the adjacent almond orchard); Bonanno, C., “La villa romana di Gerace (EN),” in Rizzo, F. P. (ed.), La villa del Casale e oltre [=Seia 15-16 (2010–2011) (2013)] 183 Google Scholar and 185 for the dating; Bonanno, C., “La villa romana di Gerace,” in Pinzino, S. Lo (ed.), Studi, ricerche, restauri per la tutela del patrimonio culturale ennese, I (Enna 2014) 88–92 Google Scholar.

3 Guzzardi, L., “Attività della sezione archeologica della Soprintendenza di Enna negli anni 1997-2000,” Kokalos 47–48 (2001–2002) 582–84Google Scholar.

4 Hay, S. and James, A., “Geophysics projects,” PBSR 81 (2013) 353–55Google Scholar

5 Liban., Or. 18.291-93.

6 A rim fragment of Hayes ARS Form 67 embedded in the (primary) white mortar floor of room 2 in this building is unlikely to be before A.D. 360: cf. Bonifay, M., Études sur la céramique romaine tardive d’Afrique (BAR S1301; Oxford 2004) 171–73CrossRefGoogle Scholar (his Form 41A); Mackensen, M., Die spätantiken Sigillata- und Lampentöpfereien von El Mahrine (Nordtunisien) (Munich 1993) 595–96Google Scholar (his form 9) with pp. 403-4 on dating. Early examples of the form are attested in destruction deposits associated with the earthquake of A.D. 365 in the E Mediterranean: Reynolds, P., Bonifay, M. and Cau, M. A., “Key contexts for the dating of Late Roman Mediterranean fine wares: a preliminary view and ‘seriation’,” in Cau, M. A., Reynolds, P. and Bonifay, M. (edd.), LRFW 1 (Oxford 2011) 18 Google Scholar.

7 The destruction débris contains two ARS lamps of Bonifay’s (ibid. 382-6) type 55, “de petite taille”, which were in circulation c.450-500, as well as ARS Hayes 61B and 81. The former is Bonifay form 38, dated by him to 420/500 (ibid. 167-70).

8 On Sicilian roof-tiles, Wilson, R. J. A., “Brick and tile in Roman Sicily,” in McWhirr, A. (ed.), Roman brick and tile (BAR S68; Oxford 1979) 20–23 Google Scholar, Type B, with my further thoughts, especially on chronology, in “Iscrizioni su manufatti siciliani in età ellenistico-romana,” in Nenci, G. (ed.), Sicilia epigrafica. Convegno Erice 1998 (AnnPisa 4, Quaderni, 1999.1-2) 538 Google Scholar. On Greek rooftiles, including the so-called ‘Laconian’ type (the earliest curved tiles), cf. Hellmann, M. C., L'architecture grecque, 1 (Paris 2002) 298 Google Scholar, fig. 402 and especially 306-8.

9 For earlier discussions of Sicilian tile-stamps, see Wilson ibid. 1979, 23-26; id., Sicily under the Roman Empire (Warminster 1990) 216-17; id. ibid. 1999, 537-42; and now most fully (for W Sicily) Garozzo, B., Bolli su anfore e laterizi in Sicilia (Agrigento, Palermo, Trapani) (Pisa 2008) 611–724 Google Scholar. The GALB(a) tiles from Piano Camera (CL) appear to be associated with 2nd- and 3rd-c. material, while the stamp-type ECNAT[i] at the same site comes from its 4th- and 5th-c. levels: Carra, R. M. Bonacasa and Panvini, R. (edd.), La Sicilia centro-meridionale tra il II ed il VI sec. d.C. (mostra; Caltanissetta 2002) 81–82 Google Scholar. It seems likely that the second half of the 4th c. represents the final period of stamping roof-tiles in Sicily. An extensive tile-fall in a building at Campanaio (AG), constructed c. 375/400, yielded only a single stamped tile ( Wilson, R. J. A., “Rural settlement in Hellenistic and Roman Sicily: excavations at Campanaio [AG], 1994-1998,” PBSR 68 [2000] 347 Google Scholar; cf. also Garozzo ibid. 688-89).

10 The apparent crescent-shaped mark on the horse’s hindquarters (fig. 6) is not a brand mark but a stray piece of superfluous clay (the feature is not present on the other examples stamped from this die).

11 The existence of some of these tile stamps was noted in passing by earlier scholars who have worked at Gerace: Cilia Platamone 1996 (supra n.1) 1687; Bonanno et al. 2010 (supra n.2) 265; Bonanno 2013 (supra n.2) 195-96.

12 The reading of the legend is uncertain because of poor stamping in the extant examples, but it is assumed that there was once a second P to the left of the crown.

13 The standard work is Muthmann, F., Der Granatapfel: Symbol des Lebens in der Alten Welt (Bern 1982)Google Scholar; cf. also on pomegranates Jashemski, W. and Meyer, F. G. (edd.), The natural history of Pompeii (Cambridge 2002) 152–54Google Scholar; Cappers, R. J. T., Roman foodprints at Berenike (Los Angeles, CA 2006) 122–23CrossRefGoogle Scholar; The seeds number between 250 and 400 per fruit. Pomegranates do not appear in the Rome brick-stamps, but it does occur once on a dolium there (CIL XV 2491r).

14 No complete example of this stamp was recovered in 2013.

15 I had originally thought, because of considerable differences between the tiles, that these marks were all added by hand, but P. Kenrick kindly informs me that he is convincd that, despite the differences (caused by varying degrees of pressure applied during stamping), the circle of marks formed part of the original die: by overlapping and so comparing images of different occurrences of the same stamp, he observed that these marks are in exactly the same position on all examples.

16 One of the tile-stamp varieties produced by legio XXII primigenia pia fidelis has its name inscribed within the shape of a dolphin: Brandl, U. and Federhofer, E., Ton + Teknik. Römische Ziegel (Stuttgart 2010) 50 Google Scholar, Abb. 52e (from Zugmantel). A dolphin appears half a dozen times on brickstamps from the Rome production ( Steinby, E. M., Indici complementari ai bolli doliari urbani (CIL XV.1) [Rome 1987] 346)Google Scholar, but always as a separate decorative element, not with letters inscribed within.

17 Salus also means ‘personal safety’, so the sense may include ‘stay safe’.

18 Generally a pale pinkish-brown, hard fabric with pale yellowish-brown core, and a smooth, possibly levigated clay matrix with abundant small white particles, probably lime, and occasional subangular particles which are shiny in reflected light. The surfaces are generally pale brown, and some have a wet-smoothed surface; a few are fired pinkish red. Such variety of colour even within a single tile often occurs in tile production, where the appearance of the final product is of little or no consequence.

19 Brodribb, G., Roman brick and tile (Gloucester 1987) 118–20Google Scholar; Brandl and Federhofer ibid. 51-52 with Abb. 54-56. The deep narrow bands framing the circular border to FILIPPIANI in Type 3 would be difficult to achieve in relief in a wooden die, so this stamp type at least was probably manufactured employing a punch made of metal, either bronze (copper alloy) or iron.

20 Adamesteanu, D., “Nuovi documenti paleocristiani nella Sicilia centro-meridionale,” BdA ser. 4, 48 (1963) 272, fig. 28Google Scholar; Wilson 1990 (supra n.9) 216, fig. 176, nos. 21-22; Bonacasa Carra and Panvini 2002 (supra n.9) 256, no. 57, fig. 39 (for the Filippiani stamp). Bonanno (2013 [supra n.9] 195) states that the villa at Piano della Clesia is of the 2nd c. A.D. but its surface finds date from between the 1st and the 5th c. (Wilson ibid. 214). The FILIPPIANI stamp here is from the same die as those at Gerace and should belong to the second half of the 4th c. Pensabene, P. (“Studi recenti sulla Villa del Casale …,” RendPontAc 83 [2010–2011] 181)Google Scholar claims that a Philippiani stamp is also attested “nel territorio di Gela”, citing Fiorentini, G., Gela. La città antica e il suo territorio. Il museo (Palermo 1984) 49 Google Scholar (it should be 1985, 51), but the latter is a reference to the Piano della Clesia example.

21 The only other example which may be related to the same production is problematical. CIL X 8045.16Google Scholar ( Avolio, F. P., Delle antiche fatture di argilla che si ritrovono in Sicilia [Palermo 1829] 57–58 Google Scholar; Fasolo, M., Tyndaris e il suo territorio I [Rome 2014) 90, no. 55)Google Scholar records a tile stamp with the reading PHILIPPIANORVM, in incuse letters, and with a hedera; according to the description, the stamp also depicted a horse. It was in Baron Astuto of Noto’s collection before the latter was sold to the Archaeological Museum of Palermo in 1830. The stamp is recorded as coming from Tindari on the N coast, but that collection was made up of finds from all over Sicily and the provenience cannot be taken as certain. The ivy leaf and the incuse letters make it seem related to the circular FILIPPIANI stamp (Type 3, although the start of the name is different), but the horse recalls the other circular stamp (Type 4), which lacks the ivy leaf but includes a crown, and also has relief letters, not incuse ones (unless the horse in the Astuto piece represents a separate stamp, as with some of our examples). The plural use of the name is unattested at Gerace and, if correctly reported, may indicate a related tile production, by two (or more) men named Philippianus. Avolio (loc. cit.) recorded the stamp as being on a circular brick (a mistake for a circular stamp?); his Tav. II, no. 7 shows the name written in a single straight line, but this is an interpreted transcript, not a facsimile. If the crown present in a type 4 stamp was misunderstood and read as an O, one can easily see how a proposed expanded reading PHILIPPIANO[rum] might have occurred.

22 There is only one example known to me of fecit being used on Sicilian tile stamps ( CIL X 8045.14)Google Scholar, a late example incorporating also a chi-rho; but in most instances there is no way of concluding whether such names are of the tile-maker or of the owner of the establishment (if different). A few examples with names in the nominative preceded by another name in the genitive are likely to represent slave tile-makers and their owners: e.g., CIL X 8045.20Google Scholar (C. SATRI PHO(e) BVS, Catania, ‘Phoebus (slave of) C. Satrius’); 22 (SOLEMNIS ET NATALIS COSSIOR(um), ‘Solemnis and Natalis (slaves of) the Cossii’).

23 I am here in disagreement with Manganaro, G., “La Sicilia da Sesto Pompeo a Diocleziano,” ANRW II.11.1 (Berlin 1988) 32–34 Google Scholar, who believes that all Sicilian tile-stamps record the names of officinatores or conductores, and never domini.

24 Ampolo, C. and Parrà, M. C., “L'agora di Segesta: uno sgardo d’insieme tra iscrizioni e monumenti,” in Ampolo, C. (ed.), Agora greca e agorai di Sicilia (Pisa 2012) 274 with pls. 309-10Google Scholar. For the tiles, see Giustolisi, V., Parthenicum e le Aquae Segestanae (Palermo 1976) 38 with pl. 33bGoogle Scholar; Müller, P., “Gestempelte Ziegel,” in Bloesch, H. and Isler, H. P. (edd.), Studia Ietina I (Zürich 1976) 63–64 Google Scholar (dating on p. 69) with Taf. 35.28-29; Bivona, L., “Le fornaci romane di Partinico (Palermo),” Kokalos 36–37 (1990–1991) 139–44Google Scholar. For their distribution, see Wilson 1990 (supra n.9), 269 with fig. 229a; Garozzo (supra n.9) 655-60. An amphora stamped with the same name is also known from Segesta: ibid. 574. If all referring to the same Onasus, active in the late 1st c. B.C. and early 1st c. A.D., he was presumably related to the Onasus Segestanus, homo nobilis, recorded by Cicero (Verr. 2.5.120) during Verres’ praetorship in the 70s B.C.

25 Popilia Paetina: Wilson 1990 (supra n.9) 216, fig. 176.12-14 with 390, n.109; id. 1999 (supra n.8) 544. An Aelia Paetina occurs on the brick-stamps at Rome (P. Setäla, Private domini in Roman brickstamps of the Empire [Helsinki 1977] 40), but this is unrelated to the Sicilian domina. Some 43 female domini (30% of the total) are attested on the Rome brick-stamps (T. Helen, Organization of Roman brick-production in the first and second centuries A.D. [Helsinki 1975] 113). One of them, Domitia Domitiani (Setäla no. 103), is known to have had an estate in Sicily ( AE 1985. 483)Google Scholar; whether she also stamped bricks and tiles at the latter is unknown.

26 CALV: Wilson 1990 (supra n.9) 215-16 with fig. 176.6-8 (on their distribution see 269 with fig. 229a); 1999 (supra n.8) 543; Garozzo (supra n.9) 681-83.

27 Bodel, J., “Speaking signa and the brickstamps of M. Rutilius Lupus,” in Bruun, C. (ed.), Interpretare i bolli laterizi di Roma e della Valle del Tevere (ActInstRomFinl 32, 2005) 61–94 (I owe this reference to C. Bruun)Google Scholar.

28 Dunbabin, K. M. D., “The victorious charioteer on mosaics and related monuments,” AJA 86 (1982) especially 82–84 Google Scholar. The horse appears half a dozen times on Rome brick-stamps (Steinby [supra n.16] 346), once with a palm branch in its mouth, and another with a palm alongside ( CIL XV 175 and 390)Google Scholar, but these are purely decorative elements unrelated to the accompanying names.

29 See most recently Matter, M., “Des chevaux du cirque: économie et passions à Rome,” in Lazaris, S. (ed.), Le cheval, animal de guerre et de loisir dans l'Antiquité et Moyen Âge (Bibl. AnTar 22, 2012) 61–72 CrossRefGoogle Scholar. For a discussion of the N African mosaics with this theme, see Ennaïfer, M., “Le thème des chevaux vainqueurs à travers la série des mosaïques africaines,” MEFRA 95 (1983) 817–58CrossRefGoogle Scholar. Similar floors in the Iberian peninsula celebrate named racehorses (e.g., Torre de Palma: Lancha, J. and Beloto, C., Chevaux vainqueurs. Une mosaïque romaine de Torre de Palma, Portugal (Paris 1994)Google Scholar; Lissón’s, M. Darder De nominibus equorum circensium. Pars occidentis (Barcelona 1996)Google Scholar is a corpus of all known named racehorses.

30 Dunbabin, K. M. D., The mosaics of Roman North Africa: studies in iconography and patronage (Oxford 1978) 93–95 Google Scholar; Rossiter, J. J., “ Stabula equorum: evidence for race-horse stables in Roman Africa,” in Afrique du Nord antique et médiévale: spectacles, vie portuaire, religions. Ve Colloque int. 1990 (Paris 1992) 46–47 Google Scholar; Benseddik, N., Cirta-Constantina et son territoire (Paris 2012) 106–9Google Scholar with col. pl. VIII. For the accurate drawings of these mosaics, see Morvillez, E., “Les mosaïques des bains d’Oued Athménia (Algérie): les calques conservés à la Médiathèque de l’Architecture et du Patrimoine,” BullSocNatAntFr 2006, 304–21Google Scholar; id., “Sur la fameuse villa de Pompéanus à Oued Athménia, près de Constantine,” in C. Blondeau et al., Ars auro gemmisque prior. Mélanges en hommage à Jean-Pierre Caillet (Turnhout 2013) 111-18. For what are almost certainly the excavated stables themselves at this site (the villa proper is unexcavated), cf. Berthier, A., “Établissements agricoles antiques à Oued Athménia,” BAAlg 1 (1962–1965) 7–20 Google Scholar.

31 Lavagne, H., “Sousse: la domus de Sorothus et ses mosaïques,” CRAI 2006, especially 1354–78Google Scholar.

32 Lavagne, H. (ed.), Mosaico romano del Mediterráneo (Paris and Madrid 2001) 80–81 Google Scholar. The sprigs with flowers on the head are standard attire for competing racehorses; by contrast, victorious racehorses are sometimes distinguished by a garland set around the shoulders and across the chest, as worn, for example, by Lenobartis on the Torre de Palma mosaic (Lancha and Beloto [supra n.29] 18, pl. 6c).

33 Landes, C., “Le Circus Maximus et ses produits derivés,” in Nelis-Clément, J. and Roddaz, J.-M. (edd.), Le cirque romaine et son image (Ausonius Mémoires 20, 2008) 413–30Google Scholar. The horse's head is depicted with a palm-branch alongside.

34 For the practice of giving additional cognomina, agnomina and signa, cf. Kajanto, I., Onomastic studies in the Early Christian inscriptions of Rome and Carthage (ActInstRomFinl II.1, 1963) 24–49 Google Scholar; id., Supernomina. A study in Latin epigraphy (Comm. Hum. Litt. 40.1; Helsinki 1966) passim; Salway, B., “What's in a name? A survey of Roman onomastic practice from c.700 B.C. to A.D. 700,” JRS 84 (1994) 127–28Google Scholar and especially 136-37 (for the Late Empire). The term supernomen occurs rarely, and not before the 3rd c. A.D. (Kajanto 1966, 5 with n.1). An agnomen should (sensu stricto) be preceded by qui et, ‘who [is] also [known as]’, but a second cognomen, even without this specification, is sometimes referred to as an agnomen without this indication. If an additional name granted in his lifetime, Philippianus may be an example of this phenomenon. It is unlikely to be a signum, another (especially Late Roman) form of additional name, since the vast majority of these end in -ius: of Kajanto’s (ibid. 1966, 76-90) list of 383 signa, only 3 examples end in -us (Marianus, Rusticulus and Secundinus).

35 The only example in Sicily recorded by Fraser, P. M. and Matthews, E. (edd.), A lexicon of Greek personal names, vol. IIIA (Oxford 1997) 451 Google Scholar is this one (based on the Piano della Clesia stamp). For the name elsewhere, cf. M. Aurelius Philippianos Iason at Prusias ad Hypium (first half of the 3rd c.) (SEG 30 1442); Tiberius Claudius Secundus Filippianus, imperial freedman and coactor, on the via Appia 5 km south of Rome ( CIL VI 1860)Google Scholar; two senators, T. Flavius Secundus Philippianus, governor of Gallia Lugdunensis c. 209 (PIR2 F 362) and his son T. Flavius Victorinus Philippianus (PIR2 F 400; cf. ILS 1152, Lyon); and Flavius Philippianus, a centurion in cohors V of legio II Traiana (ILS 2304, near Alexandria). There is also one example (3rd/4th c.) of Philippianos at Perinthus-Heraclea ( Fraser, P. M., Matthews, E. and Catling, R. W. V. (edd.), A lexicon of Greek personal names>, vol. IV [Oxford 2005] 344)Google Scholar and 7 examples in Asia Minor, 6 of them in Bithynia, all datable to the period 198/221, and one at Sardis ( Fraser, P. M. et al. [edd.], A lexicon of Greek personal names, vol. VA [Oxford 2010] 448)Google Scholar. There are also two men called Philippianos/-us of uncertain rank in Rome, one of the 2nd, the other of the first half of the 3rd c. ( Solin, H., Die griechischen Personennamen in Rom [2nd edn., Berlin 2003] 226)Google Scholar. Mention of a Philippianus also occurs in a letter of Libanius (7.90).

36 Another possibility is that the father was called Philippus (a more common name) and chose to call his son Philippianus, a natural choice. Alternatively, if putative father and son worked in the business together for a time, and if the father also was a Philippianus, they might in theory have produced tiles stamped PHILIPPIANORVM (CIL X 8045.16: see above n.21); but at Gerace tiles used in the storehouse a generation earlier than the Late Roman ‘villa’ of c. 375 bore no name stamps. For family brickworks (albeit on a much vaster scale) passing on from one generation to another, cf. Cn. Domitius Tullus and Cn. Domitius Lucanus who inherited jointly in A.D. 59 that of Domitius Afer ( Steinby, M., La cronologia delle “figlinae” doliari urbane dalla fine dell’età repubblicana all’inizio del III secolo [Rome 1977] 47–58 Google Scholar; Helen [supra n.25] 100-2; Setäla [supra n.25] 34-37).

37 Veget., Ars Mulomed. 3.6.2-4 (writing after 383 and before 450); Expos. Tot. Mundi 65; Symm., Ep. 6.33 and 42. Cf. Matter (supra n.27) 63-64, who also believes that the mention of probatio equorum on a fragment of the Taormina consular Fasti of 28/19 B.C. ( AE 1988. 625–26 and 1996. 788)Google Scholar indicates that horse-trainers of repute had been around in Sicily long before the 4th c.

38 Darder Lissón (supra n.29) 244 and 294 no. 2 (Ostia) and 315, no. 128 (a contorniate, perhaps early 5th c.).

39 Ibid. 202 and 320 no. 177 ( CIL VI 37834, l.26)Google Scholar; the creature seems, however, to have been of African origin, since the name is qualified by AF(er), ‘the African’ (and Panhormus is not attested as a place-name in Africa).

- 2

- Cited by