I INTRODUCTION

An unusual first-century c.e. funerary altar from the Via Flaminia in Rome documents two distinct stages in the lifespan of a family.Footnote 1 The epitaph on the front attests to a small family unit (Fig. 1): a father and mother united in grief over the death of their young daughter, who is pictured in the portrait above. The viewer of the monument is enjoined to let the remains of the three members of this family rest together for eternity:Footnote 2

Dis Manibus

Iuniae M(arci) f(iliae) Proculae vix(it) ann(is) VIII m(ensibus) XI d(iebus) V miseros

patrem et matrem in luctu reliquid fecit M(arcus) Iuniu[s – – –]

Euphrosynus sibi et [[ [–6?–] Actạ]]e tu sine filiae et parentium in u[no ossa]

requ(i)escant quidquid nobis feceris idem tibi speres mihi crede tu tibi testis [eris]

To the divine shades of Junia Procula, daughter of Marcus. She lived eight years, eleven months and five days. She left her wretched father and mother in grief. Marcus Junius Euphrosynus made (this) for himself and for [name erased]. Let the bones of the daughter and parents rest in one (place). Whatever you have done for us, may you hope for the same yourself. Believe me, you will be a witness to yourself.

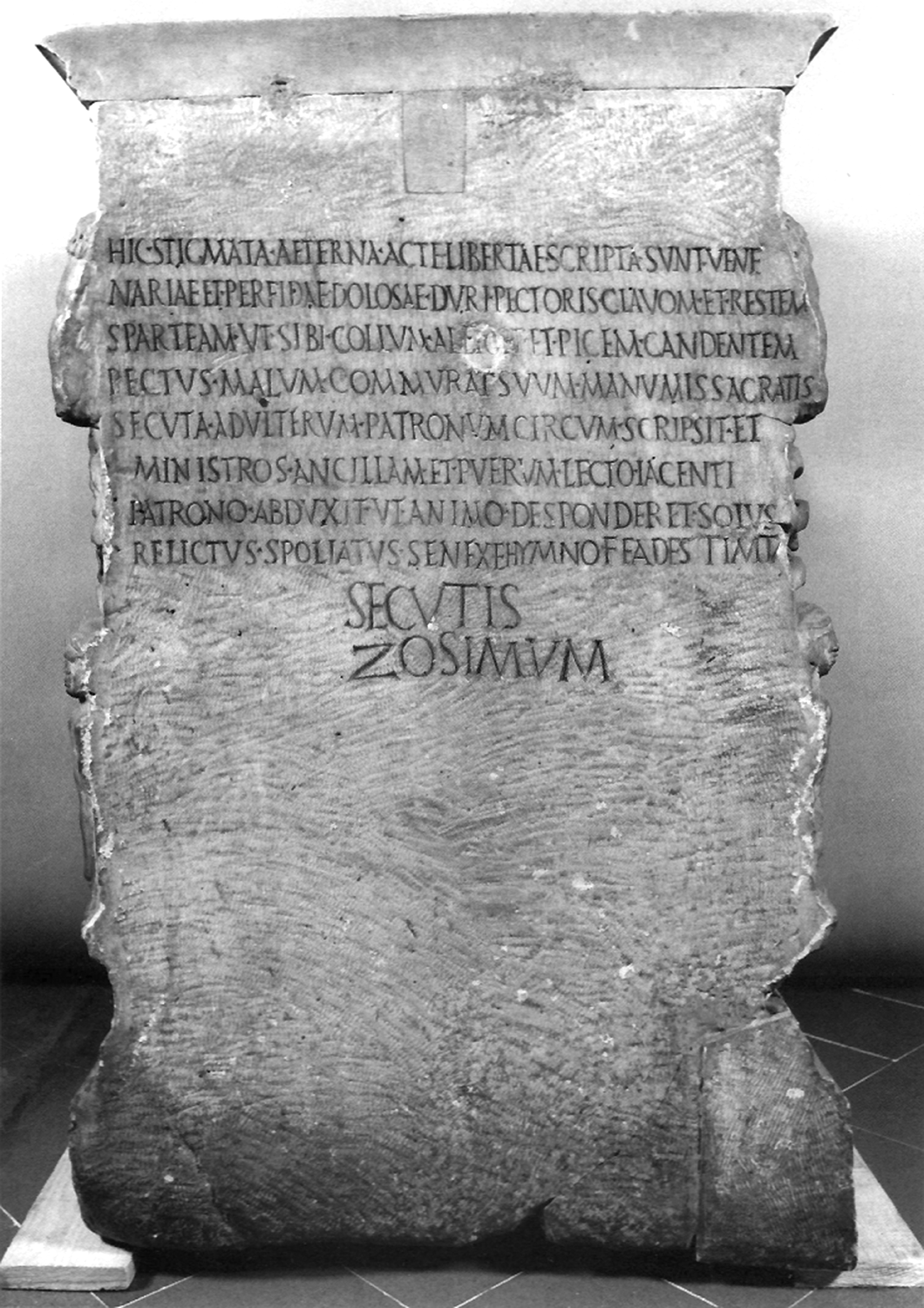

Two later alterations to the monument indicate that the harmony between the parents was short-lived. At some point after the epitaph was inscribed, the mother's name was deliberately scratched out, leaving only father and daughter in the line that had once contained all three.Footnote 3 The mother's identity was not, however, obliterated from the monument altogether. The second act, presumably contemporaneous with the erasure, was the addition of a new text hidden from view on the back of the altar (Fig. 2).Footnote 4 There someone inscribed a vicious curse directed at a woman named Acte:

Hic stigmata aeterna Acte libertae scripta sunt vene-

nariae et perfidae dolosae duri pectoris clavom et restem

sparteam ut sibi collum alliget et picem candentem

pectus malum commurat suum manumissa grati(i)s

secuta adulterum patronum circum scripsit et

ministros ancillam et puerum lecto iacenti

patrono abduxit ut animo desponderet solus

relictus spoliatus senex e<t> Hymno ⌈e⌉ade(m) sti<g>m<a>ta

secutis

ZosimumFootnote 5

Here are written the eternal marks of disgrace of the freedwoman Acte, sorceress, faithless, deceitful, hard-hearted. A nail and a hemp rope to hang her neck and boiling pitch to burn up her evil heart. Manumitted for free, following an adulterer, she cheated her patron and she abducted his attendants — an enslaved girl and boy — from her patron while he lay in bed, so that he, alone, despaired, an old man abandoned and despoiled. And the same curse for Hymnus and those who followed Zosimus.

It is not a stretch to assume that the woman condemned on the back and the woman obliterated on the front are one and the same, that Acte was Procula's mother and Euphrosynus’ wife — until, of course, she walked out on him. The author of the curse, presumably Euphrosynus himself, makes the case that the devoted mother and wife enshrined in the epitaph was a false front. In running off with another man — possibly the mysterious Zosimus or Hymnus — and stealing two enslaved persons from the household to take with her, Acte revealed herself to be an adulterer, a cheat and a thief.Footnote 6

FIG. 1. CIL 6.20905, front, Galleria degli Uffizi, Firenze (FL). (Photo: Neg. D-DAI-Rom-dig 2007.0712; Granino Cecere Reference Granino Cecere2008: no. 3451.4)

FIG. 2. CIL 6.20905, back, Galleria degli Uffizi, Firenze (FL). (Photo: Granino Cecere Reference Granino Cecere2008: no. 3451.9)

There are many features of this altar that have attracted attention — from the private damnatio memoriae on the front, to the metrical and magical content of the curse on the back — but my interest is the monument's attestation of the complex interface between relations of kinship and relations of slavery.Footnote 7 For in the curse, Euphrosynus reveals a detail of their family history that was not made explicit in the epitaph: he had held Acte as his slave before he freed her and made her his wife. Of these two legal acts, the manumission and the marriage, it is the former that is emphasised in the curse: he begins the account of their relationship with her ‘free’ (gratiis) release, identifies Acte as liberta and himself as patronus (twice) and characterises her crimes against him as commercial fraud (circum scribere). Indeed, Acte's standing as Euphrosynus’ wife is indicated only by the reference to the man she leaves with as adulter. It is their patronal connection that Euphrosynus makes central to the story he is telling about her transgressions; as he represents it, her manumission initiated a series of obligations that she, in spectacular fashion, failed to fulfil.

This article focuses on the position of women like Acte, who were married to men that had once owned them as slaves.Footnote 8 For while the record of Acte and Euphrosynus’ relationship is one of a kind, the union itself is not. Other funerary monuments from the Roman world, over 300 in total, attest that male slave owners sometimes freed women enslaved to them in order to take them as legally recognised wives.Footnote 9 This practice is by no means confined to the Roman context; comparative studies of slavery have shown that marriage was a common and almost exclusively female mode of release from slavery.Footnote 10 In what follows, I examine manumission for marriage in the early imperial Roman world — first in the case of Acte and Euphrosynus, then in legal discourse and finally in the larger epigraphic corpus attesting to patron–freedwoman marriages — in order to interrogate the extent to which marriage functioned as a pathway to freedom for enslaved women.

II ACTE'S MANUMISSION

Recent work on Roman manumission has emphasised the advantages of the practice for slaveholders. Not only did they benefit from the labour that manumission incentivised, they continued to be compensated after the grant of freedom by the institution of patronage: the culturally and legally enforced dependency of former slaves on their former owners.Footnote 11 Patronage turned manumission into a kind of exchange: slaveholders released a slave and received in return another individual subject to them, a freedman. Freedmen were useful in different but sometimes equally valuable ways. The classic example is the freed business agent who, unlike an enslaved man, had the capacity to conduct legal transactions on behalf of his patron. Freedmen also profited their patrons, though, in more diverse and less tangible ways, as, for example, dependents that provided social and political capital.Footnote 12 This conceptualisation of manumission does important work by turning our attention to the way in which modes of release from slavery were constructed to further the interests of slaveholders.

I have been using the term ‘freedman’ because the manumission of enslaved women, and especially the manumission of enslaved women for marriage, has not been integrated into this transactional model. Historians have been more focused on freedwomen's gain — free status for themselves and their children — than on the benefits that might accrue to former owners through, for example, their continuing service, labour or position in the household.Footnote 13 Even more problematic is the assumption that these types of rational considerations rarely played a role in slaveholders’ decisions to free women. It is emotional factors, especially love and intimacy, that are cited as the main impetuses behind the manumission of enslaved women.Footnote 14 The only work dedicated to the subject of manumission for marriage takes this sentimental reading even further by representing the practice as an act of sacrifice by the slaveholder on behalf of his slaves.Footnote 15 Such language mimics the rhetoric of our ancient sources — the opinion of the early third-century jurist Ulpian, for example, that early manumission should be granted on the basis of affection (affectus) — and, in doing so, reproduces the justifications of slaveholders.Footnote 16

The altar documenting Acte and Euphrosynus’ relationship serves as a good starting point for re-evaluating our approach to manumission for marriage, because it has generated just these types of readings. Interpreters have taken at face value Euphrosynus’ representation of himself as a benefactor who released Acte free of cost (gratiis), suggesting that he must have been motivated by ‘love’ (or, in one case, lust) to offer her the ‘gift’ of freedom.Footnote 17 A closer examination of his words, however, makes it abundantly clear that Euphrosynus did anticipate a return on the manumission: marriage.

We can be specific about what this marriage entailed. The key section of the curse is Euphrosynus’ articulation of all of the ways that Acte has failed him and, therefore, exactly what he expected from her: ‘Manumitted for free, following an adulterer, she cheated her patron and she abducted his attendants — an enslaved girl and boy — from her patron while he lay in bed, so that he, alone, despaired, an old man abandoned and despoiled.’ According to Euphrosynus, Acte ‘cheated her patron’ by violating the sexual norms of behaviour for a wife (taking up with an adulterer); by failing to preserve his property (stealing two of his slaves and leaving him spoliatus); and by deserting him. This last crime has multiple dimensions. He is abandoned (relictus) not only by Acte, but also by those she took with her: his enslaved attendants (ministri) and any future children that she might have borne. His description of himself as an old man (senex) is meant to elicit sympathy by pointing to his particular need for these individuals — wife, slaves and offspring — as caretakers and, especially, as heirs. In freeing Acte, Euphrosynus sought sexual fidelity, companionship and procreation.

Acte did perform some of these duties. We know from the epitaph on the front that they married and that she bore him a child, Procula. What is even more striking than what Euphrosynus says in the curse, then, is what he leaves out. For this information is nowhere to be found. In jumping directly from Acte's manumission to her departure from the household (‘manumissa … secuta’), Euphrosynus contracts the timeline of their relationship, skipping over their, at a minimum, eight-year union and the birth and death of Procula. The history effaced by the telescoping of time on the back is the same as that erased on the front: her relationship to her deceased daughter and performance of her duties as wife and mother.

Euphrosynus’ focus in the curse on their patronal relationship rather than their spousal one makes it clear that these roles were initiated by her manumission, the act that made her eligible for them. Under Roman law, it was only two free individuals with conubium who were eligible to contract legitimate marriage and produce legitimate children.Footnote 18 Offspring were, we can assume, one of the goals of this union. For iustum matrimonium was only one of Euphrosynus’ options for a sexual relationship with Acte. Enslaved women sometimes served as short- or long-term sexual partners of their owners, bearing enslaved children, and freedwomen were at times the concubinae of their patrons, bearing children that were freeborn but fatherless. Each of these unions had distinctive reproductive implications that were intimately connected to the slaveholder's estate: one resulted in additional human property, one in additional heirs to pass this property on to, and one had no effect at all on the composition or transmission of the estate. There is evidence that some Roman men made these choices strategically, and Euphrosynus may have been one of them.Footnote 19

In pointing to the duties expected of Acte as a freed-wife, Euphrosynus’ curse serves as a fitting introduction to my argument: that the manumission of enslaved women for marriage is not an exception to the transactional model of manumission. Far from representing a loss for the slaveholder, a grant of freedom and a subsequent marriage could be a rational family strategy for the acquisition of a legitimate spouse and legitimate offspring. If we have reversed the usual calculus by pointing to the patron as beneficiary rather than benefactor, we can perform the same operation for the freedwoman: while she gained freedom, it did not come without a cost. Freed-wives paid for their freedom with their conjugal and reproductive labour, to which the husband-patron obtained exclusive rights not only through the standard rights of marriage — those owed to any husband — but, as we will see, through a more controlling form of marriage.

III MANUMISSION FOR MARRIAGE IN LAW

In order to understand the position of women freed for marriage, we must now move beyond the example of a single family to examine a different body of evidence, Roman law.Footnote 20 According to jurists from the classical era, whose commentary was compiled at a much later date, the position of women manumitted for marriage was the subject of a number of legal innovations in the first and second centuries. These laws almost certainly did not introduce the practice of freeing a slave to marry her, but instead formalised what was already an existing custom, and, in doing so, constructed a hybrid status for these women. As we survey the status of freed-wives in juristic commentary, we will see that they were allowed a more limited freedom of action than other wives, with their ability to enter and exit the marriage restricted and no separation between their own property and that of their husbands.

An individual's legal capacity to manumit a slave for marriage was dependent on gender and social standing. Female slave owners were, as a rule, discouraged from manumitting and marrying men that they owned. It was not prohibited outright, but there were more restrictions on it.Footnote 21 For men, on the other hand, the manumission of a slave for marriage was much less problematic. It was only men of the highest status, the senatorial elite, who were forbidden from marrying freedwomen, whether their own former slave or someone else's. All other men eligible to contract marriage could do so with their freedwoman; indeed, their right to marry their own freedwomen was positively identified by the jurist Ulpian: ‘If any man should wish to manumit [an enslaved woman] for the purpose of marriage and he is the kind of man who could take a wife of this status without dishonour, this will be permitted for him’ (‘matrimonii causa manumittere si quis uelit et is sit, qui non indigne huiusmodi condicionis uxorem sortiturus sit, erit ei concedendum’) (Dig. 40.2.20.2).Footnote 22

The first step towards marriage was the manumission of the intended spouse. Here many owners — and by this I mean, from now on, male owners — would encounter a problem. As part of his manumission reforms, Augustus had set in place age thresholds: all manumissions of either slaves under thirty or by owners under twenty required approval by a council convened for the purpose.Footnote 23 Women manumitted for marriage were, presumably, often under the age of thirty, so to effect this manumission the owner would need to present the enslaved woman before the council and offer a valid reason (causa) for her manumission, in this case his desire for marriage.Footnote 24 The surviving lists of acceptable causae suggest that permission was often granted on the basis of an existing personal relationship — for example, if the slave was the owner's nurse, natural child or had saved his owner's life — or on the basis of a desired future relationship, such as a freedman to act as his patron's business agent.Footnote 25 Marriage is included as a legitimate justification for the manumission of an enslaved woman in two lists, and it seems to fall easily under both categories: it looked ahead to a new relationship post-manumission but, probably more often than not, also looked back to a relationship pre-manumission.Footnote 26 And yet, while it is easy to explain the inclusion of marriage as a reason for manumission, we should pay more attention to its distinctiveness among the other reasons. Manumission for marriage is more strictly regulated than any other justification for freedom — both in terms of the act of manumission itself and its effects. No other causa required an additional step beyond the act of manumission itself for the grant to be effected, nor did any other basis for manumission affect the status of the individual post-manumission. No other reason for early manumission, in other words, resulted in a particular type of freed person.

As to the additional step, the manumittor not only needed to state before the council that he wanted to marry the woman he was freeing, he also needed to show that he would indeed carry out this union. He could do so by swearing an oath that the nuptials would take place within six months of the woman's manumission.Footnote 27 If this oath was broken, that is, if the patron did not marry the woman, the manumission was invalidated. The woman would revert to slave status and the manumittor would once again be her owner rather than her patron. Her manumission, in other words, was contingent upon the marriage, and yet there was no mechanism by which she could ensure that a promised marriage went through; patrons who did not fulfill their vows were not penalised.

The necessity that marriage complete the manumission meant that there might be a period of limbo of up to six months in which the woman was only conditionally freed. The status of any children born during this period was undetermined. The early second-century jurist Celsus describes one possible scenario: ‘If a minor has manumitted a pregnant woman before the council and, in the meantime [i.e., before the marriage has taken place], she gives birth, whether the child is of enslaved or free status remains in suspense’ (‘si minor annis apud consilium matrimonii causa praegnatem manumiserit eaque interim pepererit, in pendenti erit, seruus an liber sit, quem ea peperit’) (Dig. 40.2.19). The phrase used here, ‘in pendenti erit’, refers to an issue that will be decided in the future. The child's status, then, was settled at the same time as the mother's: if the marriage went through, the mother and child were free; if not, both were enslaved.

It should be emphasised that the situation described, in which the slave woman manumitted is already pregnant, is probably not simply a juristic thought exercise. As noted, one of the purposes of a legal marriage, as opposed to concubinage or a de facto marriage, was the birth of legitimate children. It is likely, then, that a slave's pregnancy would incentivise an owner to manumit and marry her if he wanted a (free) child. Moreover, the goal of procreation might also explain the introduction of a six-month window for carrying out the marriage. The need for a prescribed time period suggests that some patrons were freeing enslaved women for marriage, but then delaying the marriage itself. If the conditionally freed slave did not, for example, conceive within a certain number of months or bear a male child, the owner might decide not to complete the manumission process.

The decision of whether or not to marry was entirely in the patron's hands, so much so that, according to Ulpian, he could actually force an unwilling freedwoman to marriage if he had manumitted her for such a purpose:Footnote 28

Marcianus libro decimo institutionum. Inuitam libertam uxorem ducere patronus non potest: Ulpianus libro tertio ad legem Iuliam et Papiam. quod et Ateius Capito consulatu suo fertur decreuisse. hoc tamen ita obseruandum est, nisi patronus ideo eam manumisit, ut uxorem eam ducat.

Marcian in the tenth book of his Institutes:

A patron cannot marry his freedwoman if she is unwilling.

Ulpian in his third book on the Lex Iulia et Papia:

Ateius Capito is said to have decided this during his consulate. This rule should be observed unless the patron manumitted her for the purpose of making her his wife.

It is here, then, that we come to the first of the mechanisms that granted patron-husbands an unusual degree of power over wives freed expressly for marriage. Consensus (agreement) was one of the requirements of a Roman marriage — unions were supposed to be entered freely and exited freely by both parties — and yet, in the case of women freed for marriage, no consent was required.Footnote 29 The husband's unusual degree of control was not based on patronage alone; according to Ulpian, Ateius Capito, consul in 5 c.e., explicitly prohibited patrons from forcing freedwomen into marriage (though the fact that he made such a ruling suggests that they might have been trying to do so). Rather, a patron could only force a freedwoman to marry him if marriage was the stated purpose of the manumission. The power to compel was predicated on a perceived exchange: the woman given freedom for marriage owes marriage.

What constituted a manumission for marriage? The purpose of a grant of freedom was most clear-cut in an under-age manumission, since the owner would have to present a justification before the council to set in motion the slave's freedom. But a patron's ability to force his freedwoman into marriage may have been possible in regular, that is of-age, manumissions as well, if the owner had declared his intent at the time of manumission. We hear, for example, that it was legal during a manumission for an owner to force his freedwoman to swear by oath (iureiurando) to marry him.Footnote 30 The mechanism that could be used to compel marriage in this case, the swearing of an oath at manumission, is the same as that used for establishing operae, the duties required of a freedman or woman post-manumission — for example, to bake bread for the patron three times a week or to perform any necessary carpentry on his house.Footnote 31 A freedwoman's marriage to her patron, it seems, was perceived to be akin to the performance of operae in the sense that both could be stipulated as a condition for freedom.

Indeed, a rescript of the early third-century emperor Severus Alexander represents patron–freedwoman marriage as a kind of replacement for operae.Footnote 32 Freedwomen were typically excused from performing operae for male patrons if they married a third party, and the case was no different if the husband and patron were one in the same; a patron-husband was not permitted to demand the performance of these duties from his freed-wife. The emperor goes on to explain, however, that though the patron-husband could not access this particular patronal privilege, he did enjoy another: ‘[You should] be satisfied with the benefit of the law, that [your freed-wife] cannot legally marry another without your consent’ (‘legis beneficio contentus esse, quod inuito te iuste non possit alii nubere’). According to Severus Alexander, it was not simply marriage that a patron-husband enjoyed, but a marriage in which balance is weighted in his control — in both the formation of the union and its dissolution.

The rule that a freed-wife needed permission to remarry was part of a larger effort to impede her from dissolving the marriage.Footnote 33 Legal commentators agreed that just as men should have the ability to compel the women they freed into marriage in the first place, so they should have the ability to compel them to remain married. It was difficult, however, to give patron-husbands this power in practice. The ban introduced by Augustus — ‘let there be no power of divorce for a freedwoman married to her patron’ (‘diuortii faciendi potestas libertae, quae nupta est patrono, ne esto’) — was not, Ulpian explains, technically enforceable (Dig. 24.2.11.pr). At issue was the civil law foundation of Roman marriage. Since marriage was based on consensus, if one party no longer intended to be married, the union was effectively terminated. The jurists sought a workaround. Rather than being denied the divorce itself, freedwomen were denied the legal consequences of a divorce, namely the ability to sue for restitution of their dowry and, as stated above, remarry against the will of their patron.Footnote 34

This solution, if followed consistently, had some consequences that were undesirable to the jurists and that they sought to remedy individually. For example, without the legal effects of a divorce, a freed-wife who left her husband would still be an automatic heir upon his death. In a clear statement that interpretation of the divorce ban should always work against the interests of the woman, Ulpian clarifies that freed-wives who have left their husbands are ineligible to inherit even though ‘the marriage continues to exist by law’ (‘iure durat matrimonium’).Footnote 35 The jurists were willing to dismantle the package of rights associated with marriage and assess their validity individually in order to diminish the wife's freedom of action.

The patron-husband's degree of control over his wife was predicated on the transaction that had taken place between them: he gave her freedom and she owed marriage in return. This rationale is made clear by a clarification around the types of manumission that produced patronal powers. If a patron-husband freed his wife according to the terms of a trust rather than voluntarily, he was not given access to the same mechanisms of control as other patron-husbands: his wife could divorce him and remarry without his permission.Footnote 36 The jurist Marcellus explains the reasoning behind his exemption: a patron did not perform a ‘benefit’ (beneficium) if the manumission was compulsory.Footnote 37 It was this beneficium, not the act of manumission itself, that created the debt which the formerly enslaved woman was meant to pay down over time as a freedwoman by means of marriage.

The laws that constrained a freedwoman's freedom of action with regard to entering and exiting her marriage served to amplify what was an existing inequality in the union. Here we come to the third and final unusual aspect of marriages between patrons and freedwomen, which seems to have applied whether or not marriage was the stated purpose of the manumission: a union between a former slave and former owner was, in effect, a marriage within a family. By the end of the Republic, most Roman marriages were ‘free’, meaning that the wife did not submit to the authority of her husband, but instead remained located within her natal family, under her father or even grandfather's authority, if he were alive. A freedwoman, legally speaking, did not have a natal family, and it was her former owner that possessed the legal and social obligations of her father. A freedwoman married to her patron, then, married into her natal family.

The effects of this intersection between marital and natal family are most readily visible in the division of property. In Roman law, spouses kept their property separate. It was only the wife's dowry that was held as common property, and only for the course of the marriage. This system gave freeborn wives some autonomy from their husband; it was their natal family, and more specifically agnatic family, that maintained some control over them. In the early imperial period, however, the claims of the agnatic family and the authority of figures like tutors were both diminished, leaving freeborn women with increased independence from both their husband and their natal family.Footnote 38 Freedwomen, on the other hand, had markedly less autonomy over the management and disposition of their estates.Footnote 39 When an enslaved woman was manumitted, her former owner retained a stake in her property and became her automatic heir and tutor in place of the agnatic family that she did not have. These external claims were not eroded in the early Empire as they were for freeborn women. Indeed, in some cases they were strengthened, as jurists continually reinforced the rights of patrons to benefit from their former slaves. The early imperial period saw, as Matthew Perry argues, ‘a growing separation between the economic rights of freed and freeborn female citizens’.Footnote 40

The disparity between the financial independence of freeborn and freedwomen is relatively clear cut, then, but to what degree was a freedwoman's position even more constrained when she was married to her patron? A freed-wife's entitlement to her dowry was one important difference. Ancient writers imply that wives could exercise some power in their household through the threat of divorce and subsequent alienation of the dotal property from their husband's control.Footnote 41 But freed-wives were barred from bringing an action for the recovery of their dowry. They could threaten divorce, then, but it was a threat with no financial consequences for their husband.Footnote 42 As for the freed-wife's control over her non-dotal property, this property was, as for all wives, held separate from that of her husband. The key difference was that for freed-wives their husband, as patron, had the ability to supervise her administration of her estate as her tutor and an interest in doing so as her automatic heir. The partition of spouses’ estates was much less meaningful when the husband had a stake in his wife's property.Footnote 43

We can attempt to gauge the property implications of husband–freedwoman marriages, but it is harder to capture the more generalised social and economic isolation that this type of union produced. Free Roman women were usually protected by — and subject to — multiple parties, any one of whose influence or resources might balance out the others. The actions of a freeborn woman's husband might be countered by her natal family. The actions of a freedwoman's patron might be countered by her husband. For freed-wives, however, all sources of authority coalesced in one individual, placing them in a uniquely vulnerable position that, as we have seen, they did not have the capacity to enter or to exit at will.

This survey of the legal position of freed-wives has been, by necessity, synchronic and therefore somewhat misleading: the legal standing of freed-wives was not static — as we have seen, there were many flashpoints of debate. The common thread, however, is the jurists’ efforts to grant patron-husbands an unusual degree of control over their freed-wives. The precise level of control varied, not just based on the interpretation of law in the period in question, but also on the circumstances of the manumission: women freed for marriage under the age of thirty or, alternatively, women manumitted by men under the age of twenty, were probably subject to the greatest degree of subordination to their patron-husbands since their freedom was conditional on marriage. A patron might compel a freedwoman to marry him even in the case of regular, of-age manumissions, though, as long as it was made clear that freedom was granted in exchange for marriage, and in both circumstances the patron had additional rights over his wife once the marriage was contracted to ensure that he received what he was owed.

Unions between freed-wives and patron-husbands were thus markedly distinct from those between spouses with no patronal connection. In the asymmetry between partners, patron–freedwoman marriage was more similar to a particular form of non-marital union: concubinage. Thomas McGinn has described concubinage as an ‘anomalous, parallel institution to marriage [that allowed] for the union of unequal partners’, but concubinage looks much less anomalous when placed beside patron–freedwoman marriage.Footnote 44 Both were species of ‘unequal unions’ enshrined in Roman law, the former a means to avoid the birth of legitimate children, the latter a means to produce them.Footnote 45 Marriage without patronage, marriage with patronage, and concubinage all operated as distinct types of union with particular familial, reproductive and financial repercussions.

IV MANUMISSION FOR MARRIAGE IN EPITAPHS

The jurists attest to the multiple legal mechanisms of control available to patron-husbands, but not the extent to which they were used or, what may have been even more significant, the extra-legal means of coercion to which patron-husbands had access — their gender, more secure economic footing and, sometimes, higher social standing, to name a few. Our other main body of evidence, the epitaphs documenting freedwoman–patron marriages, are also unhelpful in this regard. These monuments indicate the presence of patronal bonds within marriage by using what is sometimes referred to as ‘double designations’ in which one or both parties are identified by a spousal title and a patronal one, such as ‘freedwoman and wife’ (‘liberta et coniunx’) or ‘patron and husband’ (‘patronus et maritus’).Footnote 46 Beyond these markers, though, they present a neutral front. They employ the same generic expressions as epitaphs commemorating spouses unconnected through ownership, referring to each other as sweetest (dulcissimus) and dearest (carissimus) and counting the years spent together without quarrel (sine querella). It is up to the historian, then, to articulate why declarations of affection and fidelity might have a different meaning in the context of patronage.

One way to assess the relative significance of patronal and spousal bonds in these unions is to consider the personal history between the two individuals, that is, the circumstances that led to the man owning the woman that he would later manumit and marry.Footnote 47 The epitaphs that offer information in this regard indicate considerable diversity in the scenarios that produced these unions. Some were formed in overtly exploitative contexts. References to the woman's age and the length of the marriage, for example, can indicate that the marriage took place when the woman was so young that no consensual relationship could have predated purchase. In early imperial Lyon, for example, a man named Marius Cefalio married his wife Maria Dafne when she was only twelve years old, the minimum legal age for a girl's first marriage.Footnote 48 In other cases, there was a significant status, rather than age, difference that constrained the woman's exercise of agency. Some of the patron-husbands in these inscriptions are freeborn.Footnote 49 The hierarchy of status between freeborn men and enslaved women — and, of course, especially between slaveholders and their own slaves — was conducive to, if not directly productive of, abuse and coercion.

Among these freeborn patron-husbands attested in the epigraphic record are a significant number of soldiers and veterans, whose relationship to their wives was shaped by the dynamics of imperialism in addition to those of slavery.Footnote 50 Soldiers were particularly likely to form asymmetrical unions. For one, they had ready access to vulnerable women, whom they acquired directly through conquest as their spoils of war or indirectly through the thriving slave trade in military camps; sale contracts attest that soldiers bought enslaved women from each other and from traders.Footnote 51 The sexual exploitation of enslaved women in military contexts was not incidental, though, it was institutional. During the first two centuries, soldiers were barred from contracting legitimate marriages during their term of service. The ban did not prevent them from forming unions; it rather meant that the insecure unions that they did form were disproportionately with women of marginalised status.Footnote 52 The status differential between spouses in these epitaphs is likely a marker of coercive sexual practices.

More difficult to interpret are unions in which the patron-husband and his wife are both of freed status. It has been speculated that in these cases what predated the marriage was a contubernium, or quasi-marital union that could not be formalised because one or both partners were enslaved.Footnote 53 Manumission for marriage could be used as a tool of legitimisation: whichever partner was freed first could obtain ownership over the other through purchase or bequest, and then manumit their spouse causa matrimonii. This kind of emancipatory ownership is attested in other bodies of evidence; for example in Petronius’ Satyrica where a freedman boasts: ‘I bought my contubernalis so that no one could wipe his hands on her <front>’ (‘contubernalem meam redemi, ne quis in <sinu> illius manus tergeret’).Footnote 54 Even more telling is the direct reference to — and acceptance of — this practice by the jurist Marcian, who identifies a desired marriage between former conserui (fellow slaves) as the only scenario in which it should be permitted for a female patron to manumit for marriage an enslaved man.Footnote 55

Marcian clearly viewed marriages between conserui as markedly different from those between spouses with no shared history of enslavement, but we should be more cautious. Few epitaphs explicitly indicate continuity of a union before and after enslavement, as in the case of an epitaph from mid first-century Rome in which the husband, an imperial freedman, refers to himself as ‘patronus et contubernalis’ rather than ‘patronus et coniux’.Footnote 56 In most cases, the epitaphs in question simply indicate a common experience of slavery, and shared status or even a shared slave household in no way precluded exploitation, coercion and violence. What we know from these epitaphs documenting patron–freedwoman marriage is that one or both of the partners chose to commemorate the vertical patronal bond alongside the horizontal spousal one. Both were of continued relevance for defining their relationship.

We might do better to focus on this end result — the relationship produced through manumission for marriage — rather than speculate about what proceeded it. For while the divergent scenarios that I have identified surely affected the patron-husband's inclination to exert his authority, they did not change his access to it. Where patronage existed, so too did the mechanisms of control that we have identified. This observation is especially important in the case of couples using manumission for marriage to formalise a contubernium. They could achieve the recognition previously denied them, but it came at the cost of reproducing the power dynamics of slavery in their intimate relationship.

V CONCLUSIONS

Since marriage was a route to manumission that changed the quality of the union that followed, the phrase ‘manumission for marriage’ used by the Roman jurists and then taken up by historians is misleading. Especially in the case of underage manumission, the woman freed for marriage did not become ‘freedwoman’ and then ‘wife,’ but simultaneously and necessarily ‘freedwoman and wife’. The version of freedom that she experienced was located within another subordinating legal institution, marriage, that was, in turn, more restrictive than usual. Marriage was not simply a pathway to a legitimate union and to freedom; it was a pathway that qualified the union formed and the freedom attained.

This analysis of freed-wives has pointed to the inadequacy of a sharp binary between free and slave. Freed-wives inhabited a middle ground between the poles of free and enslaved, a condition shared with many others in the Roman world: public slaves, the slaves of kin, the conditionally freed, freedmen without patrons and Junian Latins (described as freedmen in life but slaves in death), to name a few.Footnote 57 Attention to the position of freed-wives, then, can help us achieve a more nuanced understanding of what freedom meant. If it was associated with autonomy — the ability to leave one's household of purchase, for example — freed-wives were not free. If it was associated, on the other hand, with promotion to a higher status within the same household or the transition from ties of ownership to those of kinship, freed-wives did achieve freedom.Footnote 58 Surely one of the most significant elements of freedom in a hereditary slave system was the ability to bear free children, and freed-wives did bear free children. What they lacked was the ability to choose the father of those children or whether they would have children at all.

We have an archival problem in trying to evaluate these different degrees and expressions of freedom. Only rarely do we get a sense of how enslaved people, and especially enslaved women, sought to structure their own lives.Footnote 59 It is for this reason that I conclude by returning to Acte and prioritising her perspective, or rather what we can trace of it from her actions. Acte chose to leave her patron-husband Euphrosynus, suggesting that whatever she gained through her marriage and whatever obstacles she faced in ending it were not sufficient for her to stay. More important than the fact of her departure, though, is the nature of her departure. She left with another man (the adulterer) and with other members of the household (the ancilla and puer). The identity of these individuals is unknown — they are usually characterised in the way that Euphrosynus represents them, as an interloper and his human property, respectively.Footnote 60 We should consider the possibility, though, that it is part of Euphrosynus’ rhetorical strategy to represent Acte's claims to these individuals as illegitimate. They may, in fact, be her family: the adulterer the man she considers her spouse, and the ancilla and puer her daughter and son, or other relations. Acte was, after all, also enslaved in this household and her connection to these individuals might stem from this period of her life; if she had born children before her manumission, for example, they would belong to Euphrosynus.Footnote 61 It is possible, then, to read Acte's actions as an assertion of free will in precisely the arena denied to freed-wives: choice of partner and choice of kin. This account of Acte's departure is speculative. I offer it as an alternative to point to the power that Euphrosynus and other slaveholders exert over who counts as free and what counts as freedom, now as then.