Introduction

In recent years, the BI idea has moved from philosophical discussion at the fringes of academia to motivate intense mainstream media attention, a growing network of global activism, and policy experiments across a diverse range of countries. In the UK, mainstream political actors have started to take the idea more seriously (Sloman, Reference Sloman2018); the Shadow Chancellor has recently expressed support for a pilot in the UK, following similar commitments from devolved regional and local authorities across the UK (Martinelli and Pearce, Reference Martinelli and Pearce2019). These developments all place BI under increasingly scrutiny regarding its practical feasibility, as well as concrete issues of policy design.

According to proponents, BI has a number of key advantages over alternative ways of organising welfare delivery. Advocates such as Standing (Reference Standing2005) emphasise that BI expands income security to all, practically eliminating gaps in coverage that arise as a result of ‘exclusion errors’ (Goodin, Reference Goodin and Van Parijs1992). As a consequence of the expansion of income security, BI would promote freedom and personal autonomy with respect to individuals’ participation in paid and unpaid activities, facilitate flexible patterns of employment (Groot and Van Der Veen, Reference Groot, Van Der Veen, Van Der Veen and Groot2000), and even provide an exit option from paid work (Widerquist, Reference Widerquist2013). BI’s non-withdrawable nature would eliminate or dramatically reduce poverty and unemployment traps caused by high marginal effective tax rates (Gamel et al., Reference Gamel, Balsan and Vero2006). According to Van Parijs (Reference Van Parijs2004), BI would reduce intrusion into individuals’ personal lives, including in relation to their partnering and living arrangements. An additional advantage of the containment of bureaucratic burdens for recipients is that BI would slash the costs of monitoring eligibility conditions to the state (Standing, Reference Standing2017: 131-132).

On the other hand, against these potential advantages, there are two significant concerns about BI that impinge upon the policy’s political feasibility. The first is the ‘conservative’ claim that BI is unaffordable. As detailed by Van Parijs and Vanderborght (Reference Van Parijs and Vanderborght2017), the thrust of the argument is that BI would be economically unsustainable due to effects on work incentives. In addition, the fiscal cost of any BI worthy of attention is excessively high in the context of other demands on public finances (Kay, Reference Kay2017). The second concern is the ‘progressive’ claim that the uniform payment structure is inadequate to cover the complex array of circumstances and needs for which social security systems are designed. In this view, BI is at best an inefficient way of alleviating poverty, and at worse would actually exacerbate it (Mian, Reference Mian2016; Goulden, Reference Goulden2018). Clearly, these vitally important criteria – affordability (or controlling cost) and adequacy (or meeting need) – appear to be in tension. This is the core conclusion of the Work and Pension Select Committee’s (2017) report, and the intuitive idea of an irreconcilable dilemma at the heart of BI has characterised much recent academic debate (Hirsch, Reference Hirsch2015; Piachaud, Reference Piachaud2018).

The central claim – that ‘an affordable BI is inadequate, and an adequate BI is unaffordable’ – has indeed been demonstrated in relation to ‘full’ BI schemes (those which consider BI as a wholesale replacement of existing social security arrangements) (Martinelli, Reference Martinelli2017a). However, BI advocates that specify a preferred model now often propose ‘partial’ BI schemes, with relatively modest payments, that run largely in parallel with existing systems of means-tested and contributory benefits (e.g. Van Parijs and Vanderborght, Reference Van Parijs and Vanderborght2017; Gaffney and Buck, Reference Gaffney and Buck2018); Atkinson’s (Reference Atkinson1996) ‘participation income’ represents an important antecedent to this line of thinking in the UK context. According to a number of recent microsimulation studies (Reed and Lansley, Reference Reed and Lansley2016; Torry, Reference Torry2016, Reference Torry2017) partial schemes enable a more desirable compromise between the goals of meeting need and controlling cost. Yet this ‘solution’ brings into focus a third criteria, which is often overlooked, which relates to the fruition of BI’s purported advantages – as outlined above – and thus, to the extent to which BI is worth pursuing at all. Partial schemes may fail to secure the advantages that motivate BI’s supporters in the first place, since means-tested and conditional benefits – and their attendant shortcomings – remain in payment.

This article contributes to debates around the potential advantages and limitations of different ways of implementing BI, in the context of greater scrutiny around the policy’s economic and political feasibility. In order to address these crucial questions, I employ microsimulation methods that allow us to engage with the static fiscal and distributional effects of alternative basic income reform scenarios in the UK context.

The core contention of this article is that BI advocates face an irreconcilable trilemma in policy design, between a) affordability / controlling cost, b) adequacy / meeting need, and c) securing the advantages of a radically simplified welfare system. The article thus confronts the overstated claims of BI critics and proponents alike. I disregard the claim that BI is unfeasible due to an irreconcilable affordability / adequacy dilemma by identifying partial schemes that arguably overcome such trade-offs. At the same time, I also consider the broader implications of seemingly attractive partial solutions, providing evidence of shortcomings that are not widely acknowledged by the proponents of such schemes – specifically that such schemes only provide income security in a very limited sense, and that they fail to liberate large numbers from means testing.

The article is divided into four main parts. The first defines some key parameters and debates relating to affordability and cost in the context of BI. The second expands upon the theoretical basis for my contention that BI advocates face a policy design trilemma. The third sets out and justifies the method and approach taken in this article, and the fourth describes the simulated outcomes of three illustrative BI models. The final section concludes with discussion of the key implications of the analysis.

Affordability and cost

As suggested above, the concept of affordability relates to the sustainability of funding – especially in terms of ensuring sufficient levels of labour market participation to generate the requisite tax revenue – but also in terms of political acceptability, given the magnitude of BI’s cost in relation to other fiscal pressures on the state. Arguably, our definition of affordability implies approximate revenue neutrality as a necessary but insufficient condition, in light of the macroeconomic orthodoxy that guides spending decisions in mature welfare states. This is simply to say that any increases in net expenditure should be (broadly) matched by increases in revenue.

Claims that BI is unaffordable are often rather ambiguous. In particular, they are often misleadingly based on gross rather than net costs. Nevertheless, we must acknowledge a number of ‘genuine’ cost problems afflicting BI. This section aims to bring some conceptual clarity to debates regarding BI’s affordability.

Gross and net costs, redistributive burdens, and marginal tax rates

Comparing the gross costs of an unconditional, universal benefit to one targeted at the poor is sure to show BI in an unfavourable light; it is on this erroneous basis that many commentators claim that BI is ‘unaffordable’ (Widerquist, Reference Widerquist2017). But gross fiscal cost is a misleading measure of the real cost of BI; it ignores the extent to which BI may be ‘self-financing’. Any increase in gross costs may be wholly or largely offset by increased tax revenue and/or reduced levels of expenditure on other welfare programmes such that the net fiscal cost of a BI is likely to be a fraction of the gross cost. A focus on gross costs neglects ‘churning’ – when people simultaneously receive payments from and pay taxes to the state – which features heavily in the case of BI. BI’s ‘redistributive burden’ comes in two forms: lost benefit entitlements due to the replacement of existing transfers with a (lower) uniform payment; and higher tax burdens. This means that the charge that basic income is wasteful or unfair because it goes to rich and poor alike is misguided: in net terms payments can be clawed back from high earners through the tax system.

If the resulting income redistribution has no behavioural implications, BI may represent a ‘transfer payment’ rather than a ‘cost’ per se. But it would represent a real cost – ‘deadweight loss’ – if associated tax rises and other features of the policy distort actors’ incentives to undertake productive economic activities (i.e. supply labour or capital). In other words, “what matter is the way in which net cost translates into a profile of new marginal taxes” (Van Parijs and Vanderborght, Reference Van Parijs and Vanderborght2017: 135). Clearly, if people face higher tax rates to fund more expansive welfare payments, this distorts their economic incentives in important ways.

Payroll tax funding and labour market withdrawal

Claims that BI’s funding base is unsustainable are founded on two hypothetical mechanisms: the effects of the removal of behavioural conditions and punitive sanctions related to benefit recipiency, and the effects of generalised increases in marginal tax rates, on work effort. Let us now briefly assess the basis of claims that these mechanisms necessarily arise because of BI’s unconditional, non-means-tested and individualised nature. Throughout what follows, I assume that BI must be funded through increases in payroll taxes. While this is not universally accepted by all BI advocates, due to the preponderance of payroll taxes among other revenue sources, it is “difficult to imagine” funding a substantial BI “without relying at least in part on this form of taxation” (Van Parijs and Vanderborght, Reference Van Parijs and Vanderborght2017: 134). Given recent and high-profile claims that BI only can funded solely through relatively minor (and politically feasible) payroll tax increases, the magnitude and likely effects of the latter are highly relevant to contemporary policy debates.

Does BI’s lack of work conditionality make it unaffordable? The argument is that it makes labour market exit easier and more desirable, thus eroding the tax base from which payments are financed. Labour market exodus would lead to increased tax burdens for remaining workers, further eroding work incentives. In fact, BI’s labour market effects are far from clear, and may well contribute to an increase in labour supply; this is even true of the removal of labour market behavioural conditions as a specific policy feature (Martinelli, Reference Martinelli2017b). Nevertheless, we must be alive to the possibility that BI’s unconditional nature threatens its financial sustainability. However, labour market behavioural responses are an empirical issue beyond the scope of this article due to the features of the static microsimulation approach used here (as noted below).

It might be supposed that the fact that BI extends to everyone, regardless of income or wealth, leads to higher taxes for net contributors. But does the absence of a means test necessarily imply higher costs? As suggested above, this is only necessarily true of the gross fiscal cost. As Van Parijs (Reference Van Parijs2004: 20) demonstrates, BI can have “exactly the same relationship between gross and net income as with a conventional [means-tested] guaranteed minimum income”. This would be the case, for example, if the positive rate of income tax paid on the first pound of earnings under a BI were set to equal the withdrawal rate under a means-tested system such as a negative income tax. Thus, if BI is a costly policy, it is not by virtue of being means-unconditional per se. An equivalent profile of net gains and losses, and of marginal tax rates, can be produced by means-tested schemes.

Genuine cost problems

Nevertheless, while it is not axiomatic that BI inevitably requires tax increases and thus imposes additional costs on the economy, it is hard to conceive of any realistic proposal for which this would not be the case. Why? One of BI’s core motivations is to provide greater material incentives at the bottom of the income scale. This requires reduced average and marginal effective tax rates for low earners than in the absence of such a motivation. Thus, if we want to honour one of the intentions of the BI – to reduce withdrawal rates and thus generate net beneficiaries further up the income scale – “one must compensate the lowering of the rate at which the lowest layer of everyone’s income is taxed by raising the rate at which higher layers are taxed” (Van Parijs, Reference Van Parijs2004: 21). This recalibration of marginal tax rates generates a ‘genuine’ cost problem.

Furthermore, in the UK as in all mature welfare states, family size and composition determine entitlement to as well as the level of payments. Means testing is carried out at the household level; assessment of ‘need’ takes into account the income of other family members, and the scope for economies of scale with respect to household expenses. As Van Parijs (Reference Van Parijs2004: 22-23) acknowledges, the individualisation of BI presents a second ‘genuine cost problem’: “the cheapest way of covering a given definition of fundamental needs therefore involves tracking the household composition and modulating the per capita level of the income guarantee accordingly”. To meet a given level of material need for individuals living alone, a BI will exceed that level for people living communally. This represents an increase in cost compared to a household-targeted system, and an increase in the tax burden of net contributors to the scheme. The alternative is that the BI meets a given level of need for people living communally, in which case it will fail to satisfy the needs of individuals living alone. At issue is the magnitude of the tax changes required by BI for schemes that also have desirable distributional consequences. These are questions to which microsimulation techniques can readily be applied, as I demonstrate shortly. First, we expand on the notion of the policy design trilemma that motivates this article.

A BI policy design trilemma

As a thought experiment, let us assume that for a fixed level of fiscal resources, a host of conditional benefits are converted into a BI. Let us also assume that the distribution of tax liabilities across the population remains constant. Such a policy would be affordable in its fiscal implications, but would clearly disadvantage existing claimants – whether recipients of social assistance or social insurance – to the benefit of the non-poor (as well as poor people not receiving benefit under the conditional system, whether through non-take-up or ineligibility). The choice between conditional and unconditional systems thus implies a clear trade-off between different forms of ‘target efficiency’, and different mechanisms for meeting need. On the one hand, under BI there should be – in principle – no gaps in coverage. Ceteris paribus, such an approach should minimise ‘exclusion errors’. On the other hand, for any given level of expenditure, the imposition of a uniform payment structure implies a loss of target efficiency in another important respect, relating to ‘inclusion errors’: “benefits paid unconditionally to everyone, willy-nilly, would naturally be expected to deliver less help to those who really need it” (Goodin, Reference Goodin and Van Parijs1992: 196).

These concerns lead to one of most important normative objections to BI: that it is seen as morally wrong to sever the link between social security and need, by making payments to rich and poor alike. The claim is that, at modest levels of payment, BI would leave many of the most disadvantaged poorer than before. But even at more generous payment levels, it is argued that BI is an inefficient way to alleviate poverty, since the same amount of money would have a greater impact if directed more narrowly at those in need. These claims form the basis of the progressive claim against BI: that it is inadequate. As defined here, adequacy thus implies the satisfaction of an (at least) equivalent level of material need as provided by existing systems – which are explicitly tailored to specific contingencies that threaten individuals’ capacities to undertake gainful employment or to earn an adequate income, or otherwise raise their living costs. While a nuanced exploration of the concept of ‘need’ is beyond the scope of this paper, we acknowledge its relational nature – adopting a broader definition of ‘need’ than mere subsistence and one that encapsulates the value of social participation – and thus take as important proxies relative poverty levels, inequality levels, and changes in income among poorer households, in comparison to the prevailing status quo.

An affordability/adequacy dilemma

Having recognised that a given BI scheme is ‘inadequate’, there are then two ways to avoid the unacceptable distributional consequences of income losses among poor (or more specifically, benefit-reliant) households. One is to increase the generosity of the uniform payment to such a level that existing claimants face no income loss under BI compared to the prevailing system. The other is to supplement the BI with conditional (means-tested or contributory) top-ups for existing claimants. Obviously, in either case, additional fiscal resources would be required to eliminate the adverse distributional effects entirely, calling into question BI’s affordability.

Under the assumption that full BI is the goal, there is a straightforward trade-off between adequacy and affordability. In order to contain net costs we must raise taxes and/or reduce expenditure on other benefits. The higher the level of BI, the greater the compensatory changes will have to be. Withdrawing other benefits as part of the scheme raises the possibility that existing benefit recipients will lose out – an unappealing distributional outcome, given that such people are more likely to live in poverty in the first place. Furthermore, eliminating other benefits would only pay for an extremely modest BI (OECD, 2017). On the other hand, increasing the level of the uniform payment helps to ensure that fewer households face significant falls in their income levels; but this obviously raises costs. This triggers the ‘conservative’ case against BI: that it acts as a disincentive for self-provision. Arguably, both of the aforementioned mechanisms through which this disincentive functions – relating to the lack of work conditionality and of the need for higher payroll taxes – are stronger, ceteris paribus, the more generous the unconditional payment.

This places BI proponents – or at least, those who advocate for the full version of the policy – ‘on the horns of a dilemma’. It is impossible to simultaneously meet need in an adequate manner (i.e. achieve a desirable distributional outcome) and also keep costs within acceptable bounds (both in terms of what is politically acceptable and economically sustainable).

From dilemma to trilemma

However, supplementing a modest BI with conditional benefits may permit a more desirable compromise between affordability and adequacy. Although retaining or introducing conditional benefits obviously increases costs compared to an equivalent BI scheme without such top-ups, the partial option would impose a lesser fiscal burden compared to a full BI calibrated to minimise losses in poor household in an equivalent manner. Thus, this compromise position improves upon the most desirable balance of distributional and fiscal outcomes achievable under a full BI; means-tested benefits targeted at the poor are ‘good value’ with respect to target efficiency.

However, this does not imply that partial schemes are unambiguously superior to full schemes. The simple reason is that in enabling a more desirable balance between affordability and adequacy, partial schemes lose some of the advantages which motivate interest in BI in the first place. Let us recall the potential advantages of BI as specified above: the expansion of income security, without gaps in coverage; the promotion of personal autonomy and freedom with respect to work; the alleviation of poverty and unemployment traps; the withdrawal of intrusion into personal living arrangements; and reductions in costly and stigmatising procedures required to administer conditional benefits. The scope of income security provided by a partial BI is much more narrowly defined. Coverage might indeed improve and expansion might approach universality, but whether a guaranteed income falling well short of existing government minimum income thresholds – let alone coming close to enabling satisfaction of so-called ‘basic needs’ – could be accurately described as ‘income security’ is highly debateable. Certainly, the extent to which a partial BI could provide an ‘exit option’ to individuals facing acute labour market disadvantage is likely to be profoundly limited (Birnbaum and De Wispelaere, Reference Birnbaum and De Wispelaere2016). Means-tested and conditional benefits would remain in payment, with all their attendant disadvantages. For example, the reduction in marginal effective tax rates would be limited for those still in receipt of means-tested benefits. While some individuals and households might be freed from the clutches of the conditional system, a large proportion of individuals would remain entangled in means testing and behavioural conditionality. Not only this, but they would arguably be disadvantaged in having to engage with a conditional regime: a) for less financial gain and b) as part of an even narrower, more identifiably poor demographic. This has the potential to increase stigma and reduce take-up of the supplementary payments; it could perhaps lead to some individuals and households being poorer than under a wholly conditional system. Finally, administrative savings would be minimal, due to the retention of bureaucratic infrastructures presumably subject to widespread sunk costs. Indeed, partial schemes may represent the worst of both worlds: BI may be unable to ‘piggyback’ on existing systems and institutions, requiring brand new ones operating alongside those that already exist. In such a situation, BI could represent greater rather than reduced administrative complexity and cost (De Wispelaere and Stirton, Reference De Wispelaere and Stirton2012).

Method

The microsimulation approach

Two forms of empirical evidence can contribute important insights into questions around affordability and sustainability: ex post (experimental) and ex ante (modelling). Each approach addresses distinct types of research agenda. Ex post evidence can take the form of ‘natural experiments’ that exhibit some of BI’s core features (e.g. Marinescu, Reference Marinescu2017) or via explicit policy experiments. Both provide insights into the nature and magnitude of likely labour market and other behavioural effects arising from BI. To date, findings appear to refute the more extreme claims that BI will lead to mass labour market exodus or socially-irresponsible expenditure (Widerquist, Reference Widerquist2005; Davala et al., Reference Davala, Jhabvala, Standing and Mehta2015). Ultimately, though, this type of evidence has a number of shortcomings in terms of addressing policy trade-offs between fiscal and distributional goals that are the focus of this article. Most crucially, evaluating the effects of unconditional payments in isolation from associated tax changes – which is the basis of most existing and planned experiments, including the ambitious Finnish experiment – does not permit analysis of the actual distributional effects of the policy as implemented, or of the tax changes that might be required to fund a BI (Kela, 2016: 52). In practice, experiments are usually targeted at specific groups (e.g. unemployed recipients of social assistance in the case of the Finnish experiment) and do not permit analysis of the pattern of winners and losers arising in the case of a truly universal payment.

Fortunately, the application of ex ante microsimulation models to questions regarding fiscal and distributional trade-offs enables researchers to overcome these limitations. Microsimulation refers to the way in which the approach simulates the effects of changes on individual ‘micro’ units – such as individuals, households, or firms – combining survey data on variables of interest across the population, and analysing how the variables change when subject to alternative (real or hypothetical) tax and benefit systems. As a result of computational advances coupled with the wider availability of requisite micro-level survey data, microsimulation methods now enable analysis of the effects of specific reforms for different demographic groups – identifying ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ from each reform in comparison to a base scenario – in addition to assessing their fiscal implications. One advantage of microsimulation is that it examines the effects of policy reforms over a representative sample, which enables an accurate picture of overall impacts on the income distribution at the national level. Others are that it avoids the practical, political and ethical issues of designing and implementing policy experiments, and facilitates the comparison of multiple alternative policy systems.

Operationalisation of variables

In order to derive fiscal cost implications, variables on taxes and benefit across the sample are ‘grossed up’ to approximate population aggregates, with sampling weights incorporated to adjust for the under- and over-representation of particular demographic and income groups in the survey. I report aggregate spending on total benefits, means-tested benefits, non-means-tested benefits, pensions, aggregate income tax and national insurance contributions (NICs) revenue, and, of course, spending on the BI itself.

Regarding distributional variables, I use equivalised disposable household income (EDHI) to account for differences in household composition. I report poverty rates as the proportion of the relevant population living in households with EDHI less than 60% of the national median. I also calculate the proportion of the population experiencing income gains and losses of varying magnitudes (expressed as a percentage of base scenario income); for these calculations, I exclude those households with negative EDHI in the base scenario. I also report income changes by (base scenario) income decile and disaggregate BI’s distributional effects by household type.

Finally, I derive indicators of the proportion of the population living in households in receipt of various means-tested benefits, and of the average value of their claims. Here I distinguish all means-tested transfers (including Housing and Council Tax Benefits), means-tested ‘out-of-work’ benefits (i.e. Income Support, income-related Jobseekers Allowance, and income-related Employment and Support Allowance), and Tax Credits. I report indicators as percentage changes with respect to the base scenario. These indicators serve to illustrate the extent to which BI schemes can be expected to deliver the policy’s broader purported goals (which depend upon emancipating people from prevailing means-tested and conditional systems).

Limitations of the approach

Claims for the credibility of our microsimulation approach should be moderated by three important caveats. Firstly, the approach adopted here is ‘static’, in the sense that the characteristics of the micro-units remain constant throughout the analysis; in other words, the following models do not allow for behavioural change.

This may be unrealistic in the context of such a wide-ranging reform as the implementation of a BI, to which we might expect some labour supply response for the reasons mentioned above. The revenue effects of tax increases are notoriously difficult to predict, and are likely to be smaller in reality than under the assumption of no behavioural change, since individuals (especially high earners) can engage in various forms of tax avoidance and reduce their taxable income (IFS, 2017).

The second limitation of our approach relates to the implicit prioritisation of payroll taxes as a source of finance, as liabilities for other taxes are not reported in the survey. Microsimulation models utilise data on household incomes; UK models use the Family Resource Survey, which captures the financial position – and other characteristics that jointly determine personal income tax liabilities and benefit entitlements – of 20,000 households. There may be strong arguments in favour of funding BI through alternative sources of tax revenues – including those relating to the accrual of economic ‘rents’ (Standing, Reference Standing2017) and Crocker’s (Reference Crocker2015) neo-Keynesian approach to money creation. In other words, the applicability of the trilemma is restricted to the prevailing status quo of social security financing arrangements, and does not extend to more radical financing proposals.

Thirdly, BI may have additional advantages that are not captured by our model and are thus not explored in this article. These include the psychological benefits of income security; the manner in which basic income is more attuned to precarious and intermittent work patterns; the positive implications of BI for take-up rates; and the effects of BI on intra-household (and gender) equality and power dynamics. Consideration of these positive effects would likely enhance the desirability of all BI schemes in relation to poverty alleviation and equality criteria.

Specification of illustrative schemes

My focus is on a comparison between three schemes that illustrate the nature of the aforementioned trilemma, involving two alternative and commonly-proposed approaches to BI design: full schemes that eliminate most other benefits, and partial schemes that leave most other benefits in payment, recalculating them to take account of the BI. Specifically, I compare a full scheme with a moderate level of payment, a generous full scheme, and a modest partial scheme.

− In the moderate full scheme, payments are based on existing ‘standard’ benefit rates: £67.01 for dependent children, £73.10 for working age adults, and £159.35 for pensioners. This scheme is based on one modelled extensively in Martinelli (Reference Martinelli2017a) in which the rationale for these specific payment rates is described in detail. In this scheme a large proportion of existing benefits – Income Support (IS), Jobseekers’ Allowance (JSA), Employment and Support Allowance (ESA), Working Tax Credit (WTC), Child Tax Credit (CTC), the Basic State Pension (BSP), Pension Credit (PC), and Child Benefit (CB) – are eliminated. Housing Benefit (HB) and Council Tax Benefit (CTB) are retained, with the BI payment taken into consideration in their calculation.

− The generous full scheme resembles the moderate scheme in terms of interactions with other welfare payments, but the BI payments are higher: £100 for dependent children and working age adults and £200 for pensioners.

− For the modest partial scheme, the existing structure of benefits is retained, and the BI payment is incorporated into existing means-tests (for IS, JSA, ESA, WTC, CTC, PC, HB and CTB). CB remains in payment. BI is paid for children. Payments are £20 for dependent children, £60 for working age adults, and £40 for pensioners. This scheme is substantively very similar to Reed and Lansley’s (Reference Reed and Lansley2016) ‘scheme 1’ and Torry’s (Reference Torry2017) ‘all at once’ scheme.

Findings: Illustrating the trilemma

Fiscal implications

Turning first to the fiscal implications of each scheme – summarised in Table 1 – gross costs are £159bn, £287bn and £388bn for the partial, moderate full and generous full schemes respectively. However, the full schemes ‘claw back’ significantly more of this expenditure through reductions in existing benefits than the partial scheme. Spending on existing welfare benefits is reduced by only £23bn in the partial scheme, compared to £124bn for the moderate full scheme and £131bn for the more generous scheme. Even so, the net costs of the full schemes remain higher than the partial scheme by a considerable margin; the partial scheme has a net cost of £136bn, the moderate full scheme £163bn and the generous scheme £257bn – the latter figure far exceeding total simulated welfare expenditure in the base scenario. Correspondingly, the tax rises required to fund the full schemes are considerably higher. For all schemes, I eliminate the personal income tax allowance (PITA) and abolish the lower and upper thresholds for National Insurance Contributions (NICs). In addition, the schemes involve increases in income tax rates (across all bands) of 3% for the partial scheme, 7.5% for the moderate full scheme, and 18% for the generous full scheme. The latter implies a combined marginal payroll tax rate of 50% on every pound earned up to the higher rate threshold (£45,000), and 70% between the higher and additional rate threshold (£150,000), above which point the marginal rate would be 75%. The tax rates required to fund the generous scheme thus appear unambiguously unaffordable, and are arguably at the limits of political acceptability for the moderate scheme too.

Table 1. Fiscal implications of selected basic income schemes

Euromod version H1.0+ (ISER, 2017), using Family Resource Survey (2014-15) input data (DWP, 2016). Base scenario original market income was £893bn, total benefit spending was £193bn (of which means-tested benefits £66bn, non-means-tested benefits £45bn, and pensions £82bn), and personal income tax and NI contributions totalled £210bn.

Distributional implications

The moderate full scheme

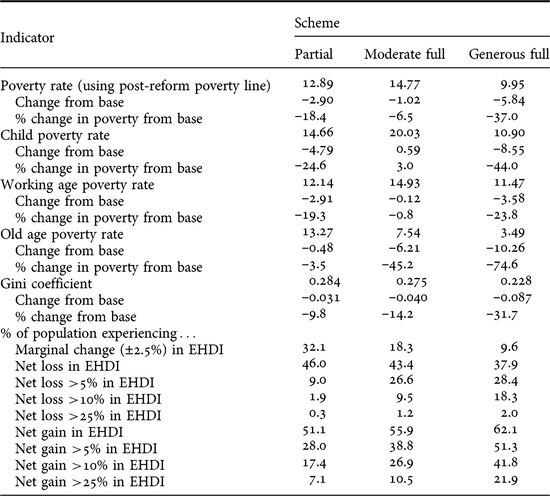

Turning to distributional effects, summarised for all schemes in Tables 2, 3 and 4, the moderate full scheme has mildly progressive implications in terms of overall poverty and inequality rates, and overall effects on the income distributional. The overall relative poverty rate falls by roughly one percentage point, and the Gini coefficient by 14%. Pensioner poverty falls by a dramatic six percentage points. However, child poverty actually increases marginally (Table 2). And although the bottom seven income deciles all see increases in their average household incomes, with the poorest decile seeing the largest proportional average increase (49%) of all, large numbers of individuals in poor households still lose out (6.6% of the poorest decile and 13.0% of decile two). More generally, over a quarter of the population experience household income losses greater than 5% of their previous income, while 9.5% of people experience losses of over 10% (Table 3).

Table 2. Distributional implications of selected basic income schemes

Table 3. Gains and losses by income decile, selected basic income schemes

Table 4. Gains and losses by household type, selected basic income schemes

In terms of the distributional effects across different household types (Table 4), the scheme is relatively unfavourable to working age households without children – those who bear the brunt of tax rises but receive less substantial household transfers. These households lose out by an average of around 4% of their previous income, with large numbers losing at least 10%. Lone parent households also experience adverse effects, with over a quarter experiencing household losses of at least 10% of previous income. The consequences for pensioners are more favourable, with both single and couple households gaining on average, although large numbers of households still lose out significantly. Generally, the impacts of the moderate full BI are relatively sympathetic to couples, due to the way that existing benefits and pensions are weighted to account for household composition while BI is strictly individualised. The moderate full scheme modelled here is clearly inadequate in terms of meeting the needs of the most disadvantaged. This is despite it being arguably at the limits of affordability, given the large tax rises required to fund it.

The generous full scheme

The generous full scheme has large and positive impacts on poverty and inequality reduction. Poverty falls by around 6 percentage points, a third of its initial level, and the Gini coefficient falls by a similar proportional amount (Table 2). Overall, the generous scheme sees the highest proportion of the population losing out by significant amounts: 18% of people experience household losses of at least 10% of previous income. However, these losses fall overwhelmingly in the upper half of the income distribution; only a small proportion of those in the poorer households lose out significantly, with 2.7% and 4.8% of deciles one and two losing at least 10% of their previous income respectively (Table 3). Turning to the detailed effects by household type (Table 4), working age households without children experience the most adverse effects. Large proportions (around 40%) of these households experience losses of at least 10% of their previous income. Among the other household types, all of which gain on average, there are only modest numbers of losers. Lone parent households experience an average gain of around 10% of previous income, while single and couple pensioner households experience average gains of 8.1% and 10.9% respectively. On balance, the generous full scheme does indeed effectively mitigate the adverse distributional effects that afflict the moderate full scheme.

The modest partial scheme

The partial scheme sees overall poverty levels fall by 2.9 percentage points and the Gini coefficient by around 10% (Table 2). Beyond these ‘headline’ figures, the partial scheme has fewer significant winners and losers than both full schemes. Only a negligible proportion of the population (1.9%) experience household losses exceeding 10% of previous income, and only 3% of the bottom two income deciles experience the same. Across the rest of the income distribution, and with the exception of the richer decile, significant income losses are rare (Table 3). These patterns are reflected in the detailed distributional analysis, which shows that the proportions of household losing over 10% of their previous income is negligible for all household types except for lone parent households, of which around 5% lose out significantly (Table 4). It is clear that in comparison to the moderate full scheme, the partial scheme represents a more effective compromise between fiscal and distributional goals. Specifically, it is more effective in terms of minimising household losses, especially among poor (benefit reliant) households, although it is less strongly redistributive overall than the alternative schemes.

Recipiency of means-tested benefits

The findings demonstrate that partial schemes appear to do a very good job at striking a favourable balance between affordability and adequacy. The question remains whether they are able to deliver on the purported advantages of BI. In order to assess this question, I report the numbers liberated from means testing under each scheme, shown in Table 5.

Table 5. Effects of selected basic income schemes on means-tested benefit recipiency and the average value of means-tested benefit claims

None of the schemes modelled here liberates the entire population from means testing. Arguably, given large disparities in housing costs, a BI is not well equipped to replace means-tested benefits designed for this purpose, and it is likely that housing benefit claims account for a large share of remaining means-tested transfers. Even so, the moderate and generous full schemes dramatically reduce the proportion of the population living in households that receive means-tested benefits (by 49% and 61% respectively) and the average value of their claims (by 42% and 53%). In contrast, the modest partial scheme only reduces recipiency of means-tested benefits by 15% and the value of claims by around 20%.

The full schemes modelled here completely liberate households from the main out-of-work benefits and Tax Credits by design. In contrast, 40% of people previously living in households reliant on the main out-of-work benefits remain so after the implementation of the partial BI. In the case of individuals living in households that receive Tax Credits, the total number falls by less than a fifth. The average value of social assistance claims would fall by a little over half, while the value of Tax Credits claims only falls by 6.6%.

These changes may be rather beneficial for those who are liberated from means testing, especially those who can escape the most intrusive forms of conditionality that characterise out-of-work benefit systems. As Reed and Lansley (Reference Reed and Lansley2016: 17) note in relation to their own partial scheme, “those still on [means-tested benefits] would receive less help [and would be] less dependent on means testing than under the present system”. This means that they would need to earn less additional income than previously in order to escape means testing entirely, an issue explored in Torry (Reference Torry2017). Nevertheless, the extent to which these schemes provide income security is severely limited due to the low payment levels; a large number of people are still required to ‘top up’ their inadequate BI payments through continued engagement with means testing. As noted above, it might exacerbate problems of low take-up if the poorest claimants were expected to engage with means testing and conditionality for less financial gain than previously. Reductions in poverty and inequality rates are far below what we would expect if fiscal resources were targeted more narrowly. Due to the need to continue administering the full range of benefits, partial BI schemes hardly seem likely to produce significant cost savings for the state. Finally, although not explored here, we know that improvements in static work incentives would be limited in comparison to relatively full schemes, because means-tested benefit reliant households would still face very high withdrawal rates on marginal increases in income (Martinelli, Reference Martinelli2017b).

Conclusion

Full BI is not feasible in the UK based on the criteria outlined in this paper. Modest full schemes cannot adequately compensate for the elimination of existing benefits without making large numbers poorer. Evidently, a uniform payment cannot adequately cover the array of circumstances for which the UK social security system is intended, unless it is pitched at a very high level. But while more generous full schemes have more acceptable distributional effects, the fiscal burden appears economically unsustainable and politically infeasible. The microsimulation evidence thus demonstrates that full BI proposals are either ‘inadequate’, ‘unaffordable’, or a combination thereof.

While the partial solution undoubtedly enables us to escape this conundrum, we are pinned on the third horn of the trilemma: partial schemes forfeit (some of) the advantages of implementing a BI in the first place. Specifically, at more modest payment levels, BI would be unlikely to give rise to a host of advantages specified in relation to the simplification of the welfare system and the liberation of individuals from means testing and conditionality. These limitations are rather unfortunate and could be fatal to political feasibility, given the fiscal exertions involved. Sceptics could be forgiven for wondering whether such schemes are worth the effort, given their modest redistributive effects, relative to more targeted options available at lower cost. The problem is not so much that these types of scheme do not have any merit or that they do not represent improvements vis-à-vis the status quo. It is that, given the considerable fiscal effort involved, they may not do enough; that “a powerful new tax engine will pull along a tiny cart (a partial and inadequate basic income)” (Gough, Reference Gough2016). Not only does this represent an important challenge to BI’s normative appeal, but it also presents a predicament for attempts to build strategic alliances between advocates with different priorities and goals (De Wispelaere and Stirton, Reference De Wispelaere and Stirton2013).

Arguably, the partial scheme is the most feasible of the three types of scheme modelled here. It is possible to design a modest partial basic income which requires relatively minor tax rises and does not significantly impoverish large numbers of low income families. The question remains whether lifting a fraction of the poor away from a system of means testing that remains in place for the majority is ethically desirable, or indeed politically realistic, given the manifest goals and objectives of BI’s advocates. Thus, BI advocates inevitably become impaled on one of the trilemma’s three horns: their preferred schemes may be inadequate, giving rise to unacceptable income losses among the poor; they may be unaffordable, necessitating excessive and unsustainable tax increases; or they may compromise the very principles underlying BI.