Introduction

Scotland’s NHS appears an archetypal example of a state institution. It remains overwhelmingly financed through general taxation, subject to central planning and governed through appointed regional Boards which act as both purchaser and provider of services, closely-controlled by central government (Greer et al., Reference Greer, Wilson and Donnelly2016). In this context, local practices that test the boundaries of this apparent monolith can illuminate ways that state practices are formed, become dominant, and change. Internationally, healthcare fundraising and philanthropy is commonplace, and often researched to assess and improve fundraising “performance” (Erwin et al., Reference Erwin, Yarbrough Landry and Gibson2015; Haderlein, Reference Haderlein2006). However, public fundraising within the NHS’s needs-based model can be understood as a foundational challenge to public and political imaginaries of both “the NHS” (Hunter, Reference Hunter, Jupp, Pykett and Smith2016), and its role within the UK’s wider welfare state. This article discusses NHS Charities within Scotland’s NHS to explore the inconsistencies, potentialities and tensions of philanthropic work at the edges of a state institution. We identify state and charitable institutional logics unevenly present within these organisations, and explore how they shape and reform ‘hybrid’ organisational practices in the contemporary Scottish health system.

NHS Charities

Although thrust into the spotlight during the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic, NHS Charities have existed since the creation of the NHS, and many evolved from voluntary associations which predated it (Gorsky and Sheard, Reference Gorsky and Sheard2006). They began as endowments, large financial balances held by voluntary hospitals before the NHS and retained to supplement NHS services. The continuation of charitable endeavours within the NHS has been a source of controversy since the earliest debates (Mohan, Reference Mohan, Gorsky and Sheard2006; Webster, Reference Webster2002). In the 1980s, the Conservative government liberalised the rules against active fundraising (Lattimer, Reference Lattimer1996) and there followed significant and rapid growth of a handful of the richest endowments into some of the most recognisable charity brands in the UK (Prochaska, Reference Prochaska1997). In 2020 there are more than 250 NHS Charities across the UK, which supplement statutory healthcare provision, often funding “add-ons” to patient care (such as arts in health) and staff development (New Philanthropy Capital, 2019). Occasionally they purchase medical equipment for which there would be no business case by a needs-based definition of the local population. The definition of NHS Charities is a regulatory one: although some English NHS Charities have since sought independent governance, the majority remain governed by the same trustees as the NHS organizations whose work they supplement. 14 of these charities, known as endowments, are in Scotland (one per territorial Health Board), where they are subject to Scottish health policy and charity regulations, and independent trustees have not thus far been permitted.

UK research on NHS Charities has paid only limited attention to the distinctive role of endowments in Scotland (Lattimer, Reference Lattimer1996). While the Scottish NHS Charities fulfil similar roles as those described above for NHS Charities UK-wide, there are some distinctive aspects. In 2000, the NHS was devolved to Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, shifting control of the Scottish endowments to Holyrood. An early act of the new Scottish Executive (now Scottish Government) was to abolish the purchaser/provider split, creating territorial Health Boards which plan and provide almost all healthcare within a geographical area. Each Health Board has an endowment and the trustees (Executive and Government-appointed Non-executive Directors) of the Health Board are also trustees of the relevant endowment funds. These funds continue in the tradition of NHS charities, to provide funds to supplement patient care, staff development and wellbeing.

However as a policy issue, the Scottish endowments have been troublesome. The Scottish NHS remains more solidly state-controlled than in England (Greer et al., Reference Greer, Wilson and Donnelly2016) and any suggestion of charitable “topping up” of straitened budgets is a point of significant political sensitivity. The Office of the Scottish Charities Regulator (OSCR) has long been critical of the governance model where the NHS Board and the charitable endowment have the same set of trustees (OSCR, 2011), creating both a potential conflict of interest and, given the respective size of Board and endowment budgets, the risk of neglect of the charities. In 2014, OSCR launched an inquiry into funding decisions by NHS Tayside’s endowment, and in 2018 reported that, while the use of funds was within the charitable purposes (advancing the health of the people of Tayside), the governance of the decision was rushed to meet the needs of the Health Board (OSCR, 2018). In a letter to a Parliamentary committee, OSCR stated that they “remain of the view that the structure put in place by the NHS (Scotland) Act 1978 gives rise to an inherent, unavoidable conflict of interest” (Robb, Reference Robb2018) and recommended legislative changes. Months later, the Scottish Government announced a review of the governance of the endowments (Freeman, 2019), which reported back at the end of Reference Freeman2019 but had not, at the time of writing, been published.

This article reports research that commenced data collection shortly before this review was announced and ended before the COVID-19 crisis propelled NHS Charities into the public eye. It seems likely that data collected six months earlier, or later, would have centred different issues. However, our primary goal here is analytical. We demonstrate the existence of two distinct models of endowment within the Scottish NHS, and then explore the contradictions therein to reflect on the current and potential role of charity within the mixed economy of UK healthcare.

The NHS, the state, and charity

All welfare states rely upon a mixed economy of provision, financing and decision-making (Burchardt, Reference Burchardt1997) via combinations of the state, the market, and voluntary and informal routes. Many analyses of shifts in the relative balance of these elements for any given good operate at the level of total spending. Powell and Miller (Reference Powell and Miller2016) argue that this underestimates the role of public and private modes of regulation and accountability. Many of the most heated debates about the mixed economy of welfare in the UK have centred whether, when and to what extent the NHS has been “privatised” (Powell and Miller, Reference Powell and Miller2016; Ruane, Reference Ruane1997; Klein, Reference Klein2015; Hunter, Reference Hunter2013). While social policy debates have often focused on charitable (and/or volunteer) service provision (Hardill and Dwyer, Reference Hardill and Dwyer2011; Alcock, Reference Alcock2010), charitable funding is another route of non-state intervention into public goods.

In exploring the work of NHS endowments in Scotland, we contribute to these debates but offer an alternative account of the publicness or privateness (Yilmaz, Reference Yilmaz2020) of these organizations’ endeavours. Our approach is inspired by wider academic debates about the state and its boundaries. There has been a general move away from rigid or monolithic definitions of states towards more fluid conceptualizations of “stateness” as a set of prosaic practices (Painter, Reference Painter2006), or cultural accounts which present the state as chimera comprising both governing practices and cultural phenomena (Mitchell, Reference Mitchell1991). These seismic conceptual moves have had relatively less of an impact in the study of the welfare state. We seek to connect these disaggregating accounts of state ontologies – the commitment that materials, practices and cultural beliefs combined enact ‘stateness’ – with literature on multiple ‘institutional logics’.

We focus on both practical organizational decision-making, and tacit values and beliefs which, we argue, define and redefine the boundaries between NHS organisations and their charities. Institutional logics are defined by Thornton et al (Reference Thornton, Lounsbury and Ocasio2012: 2) as:

“the socially constructed, historical patterns of cultural symbols and material practices, including assumptions, values, and beliefs, by which individuals and organizations provide meaning to their daily activity, organize time and space, and reproduce their lives and experiences”.

Institutional logics as a term was coined by Friedland and Alford (Reference Friedland, Alford, Powell, DiMaggio and Chicago1991) who identified a handful of over-arching logics or rationalities – including capitalism, family, democracy – which they argued shape actors’ practices. A key distinctiveness of the approach is the commitment to illuminating cultural and symbolic aspects of organisational practice, in addition to the regulatory and the material (Scott, Reference Scott2008). Thornton et al (Reference Thornton, Lounsbury and Ocasio2012) have formalised a conceptualisation of institutional logics as a resource which individual actors can draw on strategically within organisations, and which recursively shapes “individual preferences, organisational interests and repertoires of action” available within organisations. Research has explored co-existence and shifts between different institutional logics in a range of sectors and industries (Thornton et al., Reference Thornton, Jones, Kury, Jones and Thornton2005). Within healthcare, studies have identified the co-existence of (and tensions between) medical professionalism and business-like or commercial institutional logics (Harris and Holt, Reference Harris and Holt2013; van den Broek et al., Reference van den Broek, Boselie and Paauwe2014).

Breeze and Mohan (Reference Breeze and Mohan2016) argue that the logic of charity is particularly neglected in social policy scholarship, and importantly emphasise that explanatory theories of charities entail no commitment to redistribution or to helping ‘the needy’. They offer a useful table of contrasting “organising principles” for state and charitable activities, which contrast charity’s particularism, idiosyncrasy and personal, relationship-centred approach to provision, with the state’s systemic, constrained approach (Breeze and Mohan, Reference Breeze and Mohan2016: 3). Much of this table is focused on evaluative judgements rather than elaboration of the “distinctive intra-organizational processes and… different belief systems that affect all aspects of those institutions and the people who work within them, including their common practices and definitions of success” (Breeze and Mohan, Reference Breeze and Mohan2016: 3). In this paper, we explore NHS Charities as a group of organizations in which, we argue, both state and charitable logics are available and influential. This article explores the organizational choices and consequences of this hybridity.

Methods

Our study sought to understand the scale of the Scottish endowments in financial terms, and the nature of their organisation and activities. This article reports semi-structured qualitative interviews within twelve of fourteen territorial Health Boards in Scotland, plus an analysis of both the Health Board and the separate endowment accounts of all Boards. Ethical approval for the research was given by University of Edinburgh’s Usher Research Ethics Group.

Dodworth collated – where possible - both the Health Board’s overall accounts and the separate endowment accounts for the financial years 2013-2018 inclusive. Generally, Health Board accounts were easily located online and, from 2013, the endowment and the overall Board accounts were consolidated, so that high level endowment financial figures appeared in the Board’s full accounts.Footnote 1 Endowment accounts provided much more detail and were generally available online for the larger endowments. In other cases, endowment accounts – particularly for earlier years – needed to be requested by email and in one case email requests were not answered. We thus rely on endowment accounts for Lanarkshire on the OSCR website, leaving us with only two years’ accounts. These gaps aside, the dataset allowed us to explore financial size in relation to the size of the Boards these charities served, as well as variance between Boards. Data provided by OSCR allowed comparisons with other large charities in Scotland; some figures were available online (e.g. income) and others (e.g. total funds) were requested via OSCR’s public sector information procedure in April 2020.

We requested interviews within all fourteen Endowments and conducted interviews with thirteen members of staff across twelve endowments, prioritising understanding the range of endowments across Scotland, rather than building a more in-depth picture of a subset of endowments. We contacted the endowment contact email where available on the Board website or the endowment accounts, supplemented where necessary by web searches. We requested an interview with whoever managed the “day-to-day running” of the endowment, which was interpreted in different ways and indeed was mediated by the working culture of the endowment. A limitation of this data is therefore that we interviewed people occupying different staff roles and at different levels of seniority. This had consequences for the depth and type of information interviewees shared. Specifically, where a dedicated endowment member of staff was interviewed, these were typically longer and more richly detailed interviews than where the interviewee was a member of finance staff who administered the endowment alongside other budgets. Interviews were on average 46 minutes but ranged from 17 to 80 minutes. This limitation was mitigated by the fact that, to our knowledge, we interviewed finance contacts only where there were no other dedicated endowment staff – that is, we believe that the shorter responses we received in some interviews reflected the dominant mode of endowment practice in that Board; rather than being simply a function of our sample. Additionally, we asked for and sought out endowment webpages/websites and strategic plans where these were available, to support our understanding of the approach within each endowment. In our findings, we have designated two interviewee job types according to their primary function: “NHS Finance Staff Member” and “Endowment Staff Member”, whereby the former had a finance background and typically a broader remit within the Health Board, and the latter a dedicated endowment staff member with a remit to promote the endowment’s work.Footnote 2

Interviews took place between May and October 2019, conducted by Stewart or Dodworth following a semi-structured interview schedule developed jointly. Questions covered topics including the interviewee’s role, endowment staffing, endowment change over time, approaches to fundraising and spending, and future plans for the endowment. Ten interviews took place in person in offices, one in a café, and two by telephone. Interviews were, as mentioned, coloured by the timing of the Scottish Government’s independent review, which was variously seen as a worrying risk, or an opportunity to evidence best practice and push for reform. The research had arisen separately from the review, but our request sometimes generated concern, including wry remarks about the “interesting coincidence” (Board 10, male). One endowment declined to take part, and another requested after interview that their transcript not be quoted. Despite these circumstances, the qualitative data offers a rich picture of organizational divergence.

Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed. After familiarization with the dataset, authors 1 and 2 jointly agreed a deductive coding framework which we piloted on the same transcript, discussed and amended. In amending our coding frame, we recognised the significantly different accounts of organizational work heard in different endowments, and the significance of the non-availability of answers on particular questions (for example, around communications and awareness-building) in some endowments. We then proceeded to code the whole dataset, identifying two larger ‘umbrella’ codes (NHS and charitable approaches) which were informed by and can be understood as “nested” (Berg Johansen and Waldorff, Reference Berg Johansen and Waldorff2015) within Breeze and Mohan’s (Reference Breeze and Mohan2016) more abstract institutional logics of charity and the state.

Findings: financial

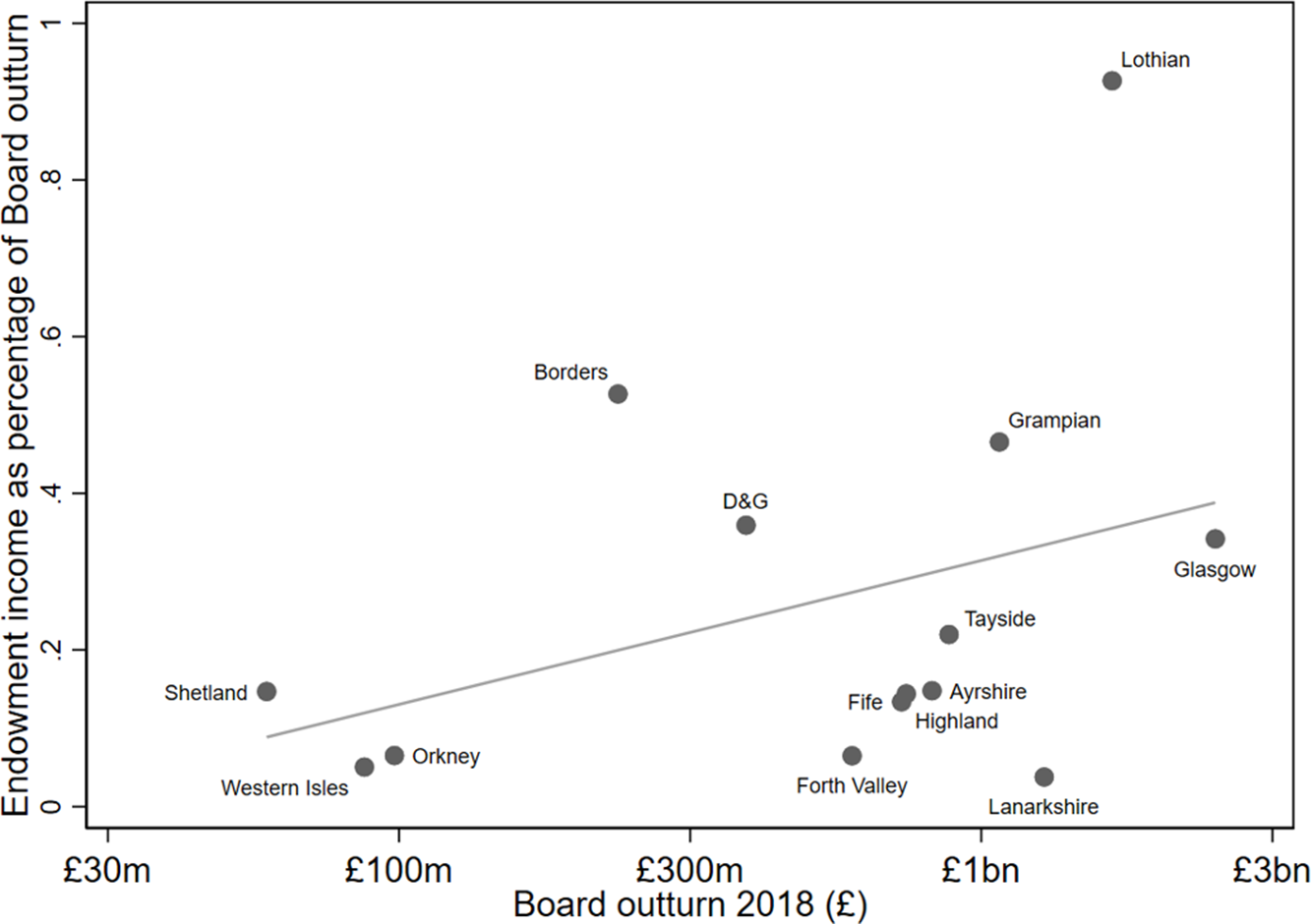

There is significant variation in the size of NHS Charities across the UK, with the population including some of the largest charities in the country, as well as many small and essentially dormant organizations. In Scotland, reflecting the relatively “flat” organizational structure of the NHS, this variation is less stark, and Scotland’s 14 endowment funds are wealthy organizations. This generally relates to historic investments yielding interest. Lothian’s Health Foundation’s income of £15.5 million in 2018 or Greater Glasgow’s endowment income of £12 million in 2019 placed these charities well within the top 1% of charities in Scotland by this measure in those years (OSCR, 2020), while a comparison with overall NHS budgets for each Board shows that all are well below 1% of annual Board outturn (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1. Scottish endowment income as % of Health Board outturn.

FIGURE 2. Endowment income by Board. Source: 2018 Endowment Annual Accounts (except Lanarkshire).

FIGURE 3. Endowment total funds by Board. Source: 2018 Endowment Annual Accounts (except Lanarkshire).

FIGURE 4. Endowment total funds per capita by Board, 2018.

The mean income for the 11 mainland Scottish endowments in 2018 was £3.4 million. Distribution varies significantly, however (see Figure 2), with 76% of total endowment income in 2018 concentrated within three “wealthy” (in absolute terms) and/or populous Boards: Lothian (including Edinburgh); Greater Glasgow and Clyde; and Grampian (including Aberdeen). These three are also the endowments with large, historic teaching hospitals.

The situation when examining these funds’ total worth is even more revealing of their scale (Figure 3). The 14 endowments’ “total funds” balance sheets amounted to around £280 million in 2018,Footnote 3 with Greater Glasgow the largest by this measure totalling over £84 million. Glasgow ranked 176 of all charities in Scotland in 2019 (there are approximately 24,000) in terms of charity income but ranked 26 by total funds.Footnote 4 Once again, over 70% of Scotland’s total endowment funds were concentrated in the same three Boards of Glasgow, Lothian and Grampian.Footnote 5

Financially, the endowments generally reflect patterns of population, but also of concentrations of wealth. Glasgow, Lothian and Grampian are indeed amongst the most populous Boards (ranked 1st, 2nd and 4th respectively). However, Lanarkshire, for example, is the third most populous Board, with the third largest health Board outturnFootnote 6 accordingly. Its very small endowment represents less than £7 per capita of the population, compared to Lothian’s £85 (Figure 4). Forth Valley and Ayrshire also serve significant populations (ranked 6th and 7th respectively) but have comparatively small endowment funds. Additionally, Lanarkshire and Ayrshire have poor populations housing the 2nd and 3rd highest proportion of income deprived populations respectively (Scottish Government, 2020). They also have a higher disease burden, reflected in poorer life expectancy.Footnote 7 In sum, these three Boards, demonstrating high need and small funds, might be said to ‘lose out’ due to the uneven spread of endowments across the country.

This collation and analysis of the accounts of Scotland’s NHS endowments suggests a picture of (perhaps surprising) wealth, unevenly spread. As figure 1 demonstrates, the larger Boards, in terms of annual outturn, do tend to have larger endowments in terms of assets, but there are notable outliers. In the next sections, we build upon this to explore how these different endowments operate in practice.

Findings: qualitative

Our qualitative interviews pointed to the co-existence of alternative approaches to endowment operation: one conservative and the other driven by reform into a contemporary charity. We see these as shaped by the more abstract logics identified by Breeze and Mohan (Reference Breeze and Mohan2016) as characteristic of charitable and state logics. While interviews suggested that many endowments were influenced by both, we identify these two ideal types as competing logics that had shaped the very different belief systems, processes and definition of success described to us within this small, and legally identical, population of study. It was evident that endowments shifted over time, as staff and trustees changed, as well as in response to political and regulatory interventions. For example, one staff member, describing organizational misgivings around fundraising to date, nonetheless acknowledged a “direction of travel” towards a more publicly visible entity, somewhat outside of his control:

I certainly see the general direction of travel that the endowment charity will come more and more to the forefront, and inevitably that will involve more and more charities engaging fundraisers. (NHS finance staff member, Board 10, male).

Scotland is a small, tightly-networked country, and endowment staff were aware of and learning from each other. However differences remined stark. Rather than suggesting the endowments exhibited one or the other logic, we note how they were differently present within our interviewees’ descriptions.

Distinctive approaches were ostensible even before the interview, in how our initial request to interview the person “responsible for the day to day running” of the endowment was interpreted within each Health Board. Several of the funds where we conducted interviews had no dedicated employees at the time of the interview, with the endowment simply contracting staff from the Board’s finance department to manage the accounts. Others had multiple staff including in strategic roles. Our interviewees therefore varied from mid- and senior-level NHS finance staff, who worked on the endowment accounts within their broader remit in the Boards, to dedicated endowment staff, including those with professional backgrounds in the third sector. This variation is a limitation in the sense of consistency and comparability of data but in another sense a finding in itself: a reflection of the predominant culture and of perceptions of how important (or risky) external relations were to the endowment (including engaging with external researchers like ourselves). There was additionally a significant gender divide, with finance staff mainly male, and fundraising or charity-oriented staff mainly female, reflecting the wider prevalence of women in charitable fundraising (Dale, Reference Dale2017).

Key practices: cautious accounting versus branding and fundraising

These different logics were discernible in how the “work” of the endowment – and the interviewee’s place within that - was characterised from the outset of each interview. In NHS-dominant endowments, work was couched first and foremost in financial terms. A significant amount of interview data expounded the diligence of the administration of the endowment funds. Several interviewees characterised these desk-based administrative practices as how endowments used to operate before OSCR was created in the 2000s: “very much a sort of low profile type of charity, it was managed in the background and just ticked along” (finance staff member, Board 10, male). Interviews in NHS-dominant endowments thus focused on the day-to-day administration and governance of the existing funds:

I just field any enquiries, making sure I get the quarterly reports for the committee, any queries, any queries or balance enquiries or, you know, coding things and journals to see what’s happening, making sure that any payments for day to day get done or prepared for weekly payment runs. (NHS finance staff member, Board 3, male)

These accountancy tasks were not absent in what we characterise as charity-dominant endowments, but were there described only briefly, before a discussion of wider activities including fundraising and marketing.

Careful and cautious accounting was thus the central activity of these endowments. NHS finance staff interviewed - including senior staff – emphasised their role in “just presenting the papers” to its trustees (finance staff member, Board 10). There was a sense that effective financial management comprised the incremental improvement of a bureaucratic machine. Proactive decisions were occasionally mentioned: in some Boards, an annual check would include moving some items of expenditure between endowment and Board accounts where they had been inadvertently misapportioned, and we also heard about funding requests making it to committee and then being rejected as squarely within the “statutory” category (and thus not eligible for charitable funding). However practices were cautious and focused on being ‘audit-proof’. Interviewees described improvements such as the rationalization of the unwieldy number of individual funds within the endowment;Footnote 8 the improvement of application forms; and improved awareness of the fund among NHS staff who might apply for funding to attend a conference or training course. All of these were in the service of improved clarity, auditability and accountability regarding endowment expenditure.

This normally entailed low visibility of the endowment fund, internally but especially to external audiences beyond the NHS.

“We must be close to being the biggest charity in the… area that the majority of the population have never heard of.” (Finance staff member, Board 5, male)

The most obvious manifestation of this was that NHS-dominant endowments did not have a stand-alone website, but a simple page within the Board’s overall website, which in some cases was not easy to locate. Some of this group of Boards had not worked-up the impact of its programmes into glossy and/or colour annual reports, and branding was not a priority. The main public work product remained the audited endowment accounts, which were not retrospectively available online for all Boards. The charity’s “good work” had thus “not been very visible” (NHS finance staff member, Board 5, male) reflecting, in our analysis, a combination of NHS ambivalence to charitable fundraising and additionally a lack of staff capacity. The nub of this approach was to be quietly, but conscientiously, “managing in the background” (NHS finance staff member, Board 10, male).

Those organizations who strove to reform the endowments into modern charities described wishing to move beyond the accountancy-based work culture. As two endowment leads explained:

[I]n the past, the endowments were sort of managed by NHS staff within the finance, you know, to be fair, in the time they had. And it was so obvious that the charity was needing managed like a charity. (Endowment staff member, Board 1, male)

Well I think, before, a lot of endowment funds in Scotland, are managed by accountants, in the finance department, as a function of finance, rather than as a separate identity. So every year, the audits person put in the report, “what are your plans for the future?”, and the endowment fund’s replied, “we have no plans”. (Endowment staff member, Board 8, female)

The introduction of a more charitable approach was in most cases attributed to a forward-thinking Executive or Non-executive Director, who advocated for the appointment of someone to take a more strategic view of future planning.

In charity-dominant endowments, such plans often included investing in branding. Several of the endowments had undertaken recent branding or rebranding exercises at the time of research, with two more in progress. In their most basic sense this entailed new logos and stand-alone websites. There is, however, a more expansive sense of branding which transforms organisational culture to be outward facing, not least in articulating the unique selling point of the endowment as a charity. In the words of one charity staff member:

It is about our brand. I mean, we’ve got a logo but I think there’s a lot more that we need to do around our tone of voice, you know, how we would talk about ourselves. (Endowment staff member, Board 2 Interview a, female)

For these reformists, this selling point lay in endowments’ localism, and branding efforts sought to embed the endowments into local consciousness as grant-givers but also, crucially, as fundraisers.

The legitimacy of public fundraising for endowments provided the most ostensible clash of the two institutional logics. For charity-dominant endowment staff, fundraising was a seamless extension of telling positive stories of the unique work of the endowment, echoing Breeze on the crucial yet “invisible role of fundraisers” (Breeze, Reference Breeze2017: 2). For more conservative Boards, public fundraising triggered deep misgivings regarding the leveraging of state-based assets, and the social and cultural capital of the NHS, to raise money.

I can’t imagine that a charity like this will ever shake cans at people or send unsolicited mail to people’s homes or any of that.

[Interviewer]: On the basis of what?

They probably feel it’s unethical to do that, and that it could potentially bring the NHS into disrepute because it would look as if we were trying to make up for a lack of government funding, which is a sensitivity.

(NHS finance staff member, Board 5, male).

The ethical ambivalence of certain kinds of proactive fundraising “alongside” the NHS was apparent and seemed deeply felt in NHS-dominant endowments.

Definitions of success

When asked about future aspirations for the endowment, one senior finance staff member in an NHS-dominant endowment replied simply: “stability” (NHS finance staff member, Board 5, male). There was nervousness in some NHS-dominant endowments about going beyond diligent financial stewardship towards active fundraising, as opposed to managing the existing endowment and spending the interest from it. Another reflected on Board ambivalence towards aiming at fund growth:

I don’t think there will be any push towards fundraising by the endowment fund in future years… One, there isn’t the capacity to do it, and two, I think with the restrictions that have been put on the endowment fund in recent years, partly from ourselves and partly because of OSCR and so on, people I think are more reluctant to donate to the endowment fund, so we’re seeing a decrease in donations to the endowment fund from the general public, and I don’t think there’s the appetite for fundraising to be done. (NHS finance staff member, Board 6, male)

NHS-dominant endowments generally had no strategic documented plan for growth, as opposed to careful management, of the fund.

By contrast, staff in charity-dominant endowments could describe at length their ambitions and strategic plans to achieve them:

I would like it to be known as the biggest local health charity in [Board 8]. I would like, when people think of giving to a health charity, that they think of the endowment fund, that they would know that we have our own diabetes fund, Parkinson’s fund, heart research fund, cancer research fund. And that all the money, all the donations that we receive, help patients here, locally, in [this Board]. So if more people would know that, I’d be very happy, and I think that would secure our future. And that’s why I’m not really bothered about aggressive fundraising campaigns, because I think we’ve got such a good story to tell, that why wouldn’t people give to us. (Endowment staff member, Board 8, female)

Capturing the impact of such spending, ensuring public recognition and therefore furthering future fundraising is key to embedding a charity logic:

So being able to acknowledge and credit the charity, put a badge on something or cut a ribbon on something we’ve funded, it enables us to then continue to raise money. (Endowment staff member, Board 2 interview a, female)

Values

While the previous sections illuminate how underlying logics were embedded into practices and goals for the endowments, we also wish to draw attention to the ways in which more tacit values were evident in our interviewees’ descriptions of their organisations. For example, the ability of charities to innovate, to rapidly adapt and to think outside the confines of the NHS was consistently cited by staff within charity-dominant endowments:

I think there’ll always be a need for a charitable sector. Because the charitable sector, I feel, can evolve quicker than the NHS, poor old NHS. The NHS has lots of hurdles to cross, to be able to do things. […] the charities are not bounded by as much legislation, so if they’re set up, and their service needs, or the service needs change a little bit, they can adapt quicker, and say, we can bring that in, we can do that. (Endowment staff member, Board 1, male)

Some charity-dominant endowments sought to leverage this agility to define their own priorities in service of the over-arching charitable aim of improved population health and wellbeing:

We’re doing some amazing things in improving health and actually by preventing people from coming into hospital by supporting their health in the community, that was helping NHS [Board] as well. So it didn’t just need to be grants for hospital x, y or z. We could work directly with communities. (Endowment staff member, Board 2 Interview a, female)

This departed from conventional NHS-dominant endowment practice, where funds were generally used to improve population health and wellbeing via improvements to existing NHS services. Increasing and diversifying spending – rather than having funds that just “accumulate forever” (Endowment lead, Board 8, female) – is a characteristic charitable value, backed by charity regulations that advise against significant accumulation of financial reserves.

I was appointed, to try and move some of the funds round, rather than just them accumulate forever more… I went out looking for projects that would, the endowment fund, especially the general fund, could finance… So I’m encouraging the turnover in funds. (Endowment staff member, Board 8, female).

This openness to funding a diversity of activities contrasts with over-arching commitments to caution and probity within conventional state spending, where expenditure must be justified in what Breeze and Mohan (Reference Breeze and Mohan2016) describe as a “teleological” manner.

A deep-seated commitment to state logic norms of systemic, not idiosyncratic (Breeze and Mohan, Reference Breeze and Mohan2016: 3), provision was apparent in NHS-dominant endowment reticence about the particularism of charity logics. Several interviewees acknowledged that the ease of, or public appetite for, fundraising a service might start to influence NHS spending decisions if fully embraced. Two charity-dominant endowment representatives described the ongoing tension of ensuring that “fundable” projects (classic examples being children’s services) were prioritised by the same clinical and managerial judgement as any other major decision.

We need to make sure we’ve got a vision for the Health Board and then pick the project [for fundraising] between us… I think it was a really pivotal moment for us because I think it was, you know, sort of almost a victim of its own success. The fundraising had done so well and it – I don’t want to say it was influencing the agenda – but it did a little. It became sort of an influence on where things were. but we thankfully reined it back in and I think we always have to…we’ve learned that lesson, we always have to position everything within the overall strategy and what’s right for the services. (Endowment staff member, Board 9, female)

Because it can be a bit of a conflict between fundraising. Because we will say, “well I think this one’s really fundable, we could really fund it”, and the services can say, “but this is the one that’s going to have impact”. So then who makes that decision? (Endowment staff member, Board 2 interview b, female)

Discussion

In Scotland, NHS Charities spent decades existing mostly on balance sheets: budget lines whose trustees had not actively sought the role, operating with a minimal dedicated staff to drive them forward. In many ways they more closely resembled foundations than modern, professionalised charities. This study demonstrates a change in activities across some of the Scottish NHS Charities, along with continued ambivalence about this shift within more traditionally-run endowments. However, the descriptions of our interviewees suggest, beyond an empirical change in activities, more substantive differences in the underlying practices, definitions of success, and values through which endowment staff explained and justified their work. Engaging with theories of institutional logics allows us to capture the extent to which choices about organisational change are enmeshed within broader ‘ideal types’: that of the state, and of charity.

The state logic can be understood as the dominant model of the Scottish NHS endowments: present in all endowments; reactive; and focused on careful and cautious accounting of funds. The charity logic we also identified in some, but not all, endowments was a more recent ‘import’ or ‘add on’ to a smaller number of organisations, where new personnel with different training and skillsets had been appointed. Those skillsets, and their associated practices of fundraising and community-building, were not present within the more traditional endowments. Where a charitable institutional logic was present, interviewees described the expansion of endowment activities beyond the basic pursuit of diligence and stability. This involved not merely additional activities but a wider redefinition of the endowments, reflecting Thornton and Ocasio’s (Reference Thornton and Ocasio1999: 806) assertion that “the assumptions, values, beliefs, and rules that comprise institutional logics determine what answers and solutions are available and appropriate in controlling economic and political activity in organizations”. What might a charitable institutional logic mean for NHS organizations seeking to mitigate the impacts of austerity?

One key contribution of the institutional logics approach is a focus on both the material and the cultural-symbolic aspects of organisations (Scott, Reference Scott2008). Endowments where the charity logic was dominant were more engaged with local publics, both through material practices of communication and through their values and goals (including external visibility). Within the more reactive model of NHS-dominant endowments, public initiative was limited to broadly unsolicited donations from grateful patients. Charity-dominant endowments created more opportunities for the cultivation of a sense of community around the local NHS through fundraising events, web appeals and branded posters and fundraising materials. Major capital appeals mobilised local identity and communal affection for local manifestations of the NHS; primarily via justifying and publicising the need for particular material objects and buildings. However, this community engagement has its limitations. While this was public-facing work, it was not consistently public-initiated work. A demand for particular equipment or space was generally identified within the organization and then ‘sold’ to the, generally highly receptive and enthusiastic, wider public. The success of particular fundraising sub-projects within NHS-defined campaigns, driven forward by passionate individual members of the public, arguably shaped the emergent campaign but did not define it. Interviewees raised the risk of publicly popular “fundable” initiatives moving up the Board agenda because of the potential income stream and described how the risk was managed. The media furore when Glasgow’s endowment funded a feasibility study for the creation of safe injecting facilities in the city (NHS GGC, 2018) points to the parallel risk when clinical evidence and public opinion come into conflict. Nonetheless, a key impediment to locally-accountable healthcare organizations in the Scottish NHS is tight central Government control (Greer et al., Reference Greer, Wilson and Donnelly2016; Greer et al., Reference Greer, Wilson, Stewart and Donnelly2014). For better or worse, local fundraising creates the potential for particularistic experimentation and the tailoring of local services.

One key objection to charitable funding within the NHS is that it may enable wealthy areas to supplement and improve their services, reinforcing the inverse care law (Tudor Hart, Reference Tudor Hart1971). Scotland’s NHS structure, with regional Boards and a resource allocation formula which seeks to mitigate deprivation (Auditor General for Scotland, 2018), makes this somewhat less of a risk than, for example, in England’s more fragmented NHS. All the Scottish endowments’ wealth and spending is dwarfed by the budgets of their respective Health Boards (see figure 1), which means even the wealthiest endowment makes marginal financial contributions to local healthcare. In terms of discrepancy between Health Boards, table 1 shows the territorial Boards’ outturn, endowment wealth (assets and income), and then the presence of a standalone endowment website (as a proxy for public profile). Our project demonstrates examples of wealthy Endowments which consolidate their wealth by investing in fundraising expertise and activities (Lothian), and poorer Endowments which do not fundraise, staying small (Lanarkshire). However there are outliers, such as Greater Glasgow & Clyde which has a large and historically wealthy endowment but limited public profile and efforts at fundraising. Table 1 suggests that organisational choices are not dictated by prior endowment wealth. Some of the larger endowments remained largely static, eschewing fundraising, and some of the smallest endowments launched proactive fundraising campaigns. These choices are illuminated by our qualitative data, which often described a proactive staff member or trustee within the Board who advocated for investment in endowment staffing. Once in place, there was a degree of path dependency as a charitable logic was ‘added in’ to the endowment. Endowments which invested in staff with professional fundraising skills (hired on the assumption they will “pay their own way” in increased endowment revenue) were reshaped by those staff bringing not just skills and experience but distinctive institutional logics into the organisations.

TABLE 1. Table showing Health Board outturn, Endowment assets and income, and whether endowment has own website

Conclusion

Research has often stated the centrality of the NHS to British identity, and in the 21st Century the NHS has repeatedly become a focal point for public discourse during moments of national crisis (such as the Brexit referendum and the COVID-19 pandemic) (Hunter, Reference Hunter, Jupp, Pykett and Smith2016; Fitzgerald et al., Reference Fitzgerald, Hinterberger, Narayan and Williams2020). The remarkably successful COVID-19-related fundraising campaign of NHS Charities Together focused wider attention on to a set of organizations which, we argue, operate at and thus illuminate the boundary between the NHS as a state entity and charitable efforts to meet community health needs. We focus on only the Scottish endowments, operating in a policy context of widespread ambivalence and occasional opposition to charitable fundraising in the NHS, which contrasts with the enthusiastic, if problematic, embrace of third sector organisations in English social policy since the late 1990s (Alcock, Reference Alcock2010).

Scholars have developed novel and sophisticated accounts of ‘stateness’ as not merely a legal or institutional form, but something enacted through the symbolic and the prosaic work of institutions (Painter, Reference Painter2006). This paper uses the example of NHS charities in Scotland to illuminate how the stateness of the NHS – operationalised in a focus on diligent accounting of budgets in service of meeting systemic, objectively-defined needs – is unevenly articulated in opposition to an alternative charitable institutional logic which prizes visibility, innovative projects, and a diversity of public goods. The ambivalence identified around fundraising in the charitable sector (Breeze, Reference Breeze2017) is significantly magnified in the NHS, where a foundational imaginary of the institution rests upon not goodwill and generosity but compulsory and equitable financial contributions (Hunter, Reference Hunter, Jupp, Pykett and Smith2016); what Ruane (Reference Ruane1997) analyses as the “collectivism of funding”.

This article offers an initial exploration of a set of organisations which have been marginal or absent from recent social policy scholarship. The study prioritised a health system-wide perspective over in-depth exploration of a smaller number of organisations, and there is scope for more research. Nonetheless, this paper argues that the Scottish endowments display differing approaches to navigating the state-charity boundary. Dilemmas around raising and spending funds within the endowments are negotiated by staff with different professional backgrounds, drawing on distinctive institutional logics. The potential of a charitable logic to engage communities directly and locally in their services has particular value in Scotland’s centrally-managed health system. However, charitable logics also tend towards the particular and the additional, rather than the universal and the essential (Breeze and Mohan, Reference Breeze and Mohan2016). This meant that many Scottish endowments were cautious with regards to both fundraising and spending, sometimes shying away from more innovative charitable projects. These anxieties were not (only) about the risks of controversy, but in some cases also concern that a free and needs-based service would be eroded by calls for voluntary financial contributions. While policy debates have focused on questions of charity governance, NHS Charities also have more far-reaching risks and possibilities for how the ‘publicness’ (Yilmaz, Reference Yilmaz2020; Ruane, Reference Ruane1997) of healthcare is understood in the NHS.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all participants for their time. This research was funded by the Carnegie Trust for the Universities of Scotland (grant number RIG007863) and writing-up was in part supported by the Wellcome Trust (grant number 219901/C/19/Z). Additionally, the paper was improved by feedback at a virtual PACE writing workshop in June 2020. Our sincere thanks to Dr Diarmuid McDonnell, who reviewed the financial data and helped create the figures, and to Julia McDonald for her insights on NHS accountancy.

Competing Interests

The authors declare none.