Introduction

Within the last two decades, studies on the health and economic benefits of parental leave have highlighted the importance of providing paid leave to new mothers and fathers. A substantial body of research has shown more generous durations of paid maternity leave to be associated with improved child and maternal health outcomes, including increased rates of exclusive breastfeeding (Baker and Milligan, Reference Baker and Milligan2008; Huang and Yang, Reference Huang and Yang2015) and child vaccinations (Berger et al., Reference Berger, Hill and Waldfogel2005; Daku et al., Reference Daku, Raub and Heymann2012), decreased rates of infant mortality (Ruhm, Reference Ruhm2000; Tanaka, Reference Tanaka2005), and improved well-being of mothers (Avendano et al., Reference Avendano, Berkman, Brugiavini and Pasini2015; Chatterji and Markowitz, Reference Chatterji and Markowitz2012). Several studies have also found that paid leave may be positively associated with women’s labor force participation and long-term earnings (Stier and Mandel, Reference Stier and Mandel2009; Waldfogel, Reference Waldfogel1998). Although research on the effects of paid paternity leave is only emerging, initial studies have associated fathers’ use of leave with greater gender equality, through more equitable sharing of household responsibilities between parents and increased participation in child care (Haas and Hwang, Reference Haas and Hwang2008; Kotsadam and Finseraas, Reference Kotsadam and Finseraas2011; Nepomnyaschy and Waldfogel, Reference Nepomnyaschy and Waldfogel2007; Patnaik, Reference Patnaik2017; Schober, Reference Schober2014; Tanaka and Waldfogel, Reference Tanaka and Waldfogel2007). Fathers taking leave can also have positive effects on child cognitive development (Huerta et al., Reference Huerta, Adema, Baxter, Han, Lausten, Lee and Waldfogel2013) and child-parent bonding (O’Brien, Reference O’Brien2009). Moreover, evidence shows that paid leave for partners may support breastfeeding (Flacking et al., Reference Flacking, Dykes and Ewald2010) and lower rates of maternal depression (Page and Wilhelm, Reference Page and Wilhelm2007) through increased partner involvement and support.

Paid leave can also have longer-term benefits by protecting new parents from wage or job loss after the birth of a child, thereby reducing the likelihood of new families falling into poverty (Heymann et al., Reference Heymann, Sprague, Nandi, Earle, Batra, Schickedanz, Chung and Raub2017; Maldonado and Nieuwenhuis, Reference Maldonado and Nieuwenhuis2015; Misra et al., Reference Misra, Moller, Strader and Wemlinger2012). In high-income countries, poverty has been inversely associated with children’s physical and mental health into adulthood, with effects being particularly large when poverty is persistent and experienced during early childhood (Chaudry and Wimer, Reference Chaudry and Wimer2016; El-Sayed et al., Reference El-Sayed, Scarborough and Galea2012; Strohschein and Gauthier, Reference Strohschein and Gauthier2017).

Given these well-documented benefits of paid parental leave, a large portion of work-family research is focused on the duration and availability of parental leave to new mothers and fathers (ILO, 2011; Koslowski et al., Reference Koslowski, Blum and Moss2017; OECD, 2017; WORLD Policy Analysis Center, 2015). However, this research is commonly conducted in the context of a different-sex parent household, with one mother and one father. There has yet to be systematic research to understand the availability of paid leave to same-sex parent households. Failing to extend paid leave policies to same-sex parents may deprive both parents and children of the benefits of paid parental leave, and place families at an increased risk of poverty directly after the birth or adoption of a child. This is particularly important given same-sex couples are more likely to be economically disadvantaged than different-sex couples (Badgett et al., Reference Badgett, Durso and Schneebaum2013; Gates, Reference Gates2013; Prokos and Keene, Reference Prokos and Keene2010).

There have been notable advances towards achieving equal rights for same-sex parent families. A report published in early 2017 noted that nearly half (47%) of OECD countries recognize same-sex marriage, and slightly over half (53%) allow joint adoption by same-sex parents (ILGA, 2017). Since the publication of this report, Australia and Germany became two additional OECD countries to recognize same-sex marriage (Cave and Williams, Reference Cave and Williams2017; Smale and Shimer, Reference Smale and Shimer2017). However, full realization of equality also requires being able to enjoy the same family rights as different-sex couples after marriage and adoption, including access to paid parental leave. The 2007 Yogyakarta Principles, which outline key human rights for LGBT persons, directly address the issue of family benefits; Principle 24 emphasizes the right to start a family and states that “no family may be subjected to discrimination on the basis of the sexual orientation or gender identity of any of its members, including with regard to family-related social welfare and other public benefits” (Yogyakarta Principles, 2007). Furthermore, a 2013 OECD report called on countries to ensure labor policies support parenting regardless of “partnership status” (OECD, 2013). More explicitly, a 2016 directive from the European Parliament emphasized the need for parental leave policies that incorporate same-sex couples and commended the few member states that had already implemented inclusive policies (European Parliament, 2016).

The scarcity of research examining work-family policies in relation to same-sex parent families has led researchers to call for more in-depth data on their family experiences, including the application and impact of parental leave (King et al., Reference King, Huffman, Peddie, Goldberg and Allen2012; Languilaire and Carey, Reference Languilaire and Carey2017; Tammy and Lillian, Reference Tammy, Lillian, Tammy and Lillian2016). A recent decision by the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR) specifically highlights the need to identify legal barriers to equal access to paid parental leave. In 2018, the ECHR denied a French woman paternity leave after her female partner gave birth. The Court denied access based on paternity leave being “conditional on the existence of a parental relationship” and “designed to allow fathers to play a greater role in their children’s upbringing” (European Court of Human Rights, 2018). While this specific case was filed in 2004, and French legislation has since been amended to extend leave to all partners, the decision will likely have lasting implications for other European Union countries, particularly those that have not updated legislation to explicitly guarantee parental leave to same-sex partners.

The purpose of this analysis is to examine paid parental leave policies in OECD member states and determine whether same-sex couples receive leave entitlements that are comparable to those of different-sex couples. Although prior studies have conducted cross-country comparisons of paid leave durations in OECD and other high-income countries, they have focused on leave that is available to different-sex parents (Koslowski et al., Reference Koslowski, Blum and Moss2017; OECD, 2017). To expand upon this previous research, we conduct in-country comparisons between various family types, examining the total summed duration of parental leave that is available to two parents in a different-sex couple, a same-sex female couple, and a same-sex male couple. Specifically, we aim to report the number of OECD countries where same-sex couples receive equal durations of paid parental leave as different-sex couples in cases of birth and in cases of adoption. Further, when there are in-country differences between family types, we detail the extent of these disparities by examining the differences in parental leave durations between different-sex and same-sex couples.

Data and Methods

This study utilizes an original quantitative database of paid parental leave policies in force as of September 2016 in 34 OECD member countries. OECD countries were selected as the sample for this study due to the relative strength of their parental leave policies, as well as growing recognition of legal and civil rights for LGBT families in regional agreements (Adema et al., Reference Adema, Clarke and Frey2015; Valfort, Reference Valfort2017). Our multilingual, multidisciplinary research team gathered and analyzed national labor, social security, and parental leave legislation, which was accessed through the ILO’s online database, NATLEX (ILO, 2016). Official government websites on national paid leave policies were referenced for 33 countries to confirm country approaches to regulating and implementing legislation; no official website was found for Turkey. Trusted secondary sources – including the European Commission’s Mutual Information System on Social Protection (MISSOC) and country reports from the U.S. Social Security Administration and the International Network on Leave Policies and Research – were also referenced for all 34 countries to further verify legislation and official websites (European Commission, 2016; Koslowski et al., Reference Koslowski, Blum and Moss2016; U.S. Social Security Administration, 2016).

For each country, two analysts independently reviewed sources and coded indicators on key aspects of paid parental leave policies, including the duration of benefits and the inclusion or exclusion of same-sex couples. The two analysts subsequently compared their coding and reconciled any inconsistencies. This approach builds on previous work examining paid parental leave in comparative perspective (Heymann and Earle, Reference Heymann and Earle2010; Heymann and McNeill, Reference Heymann and McNeill2013; Heymann et al., Reference Heymann, Raub and Earle2011).

Measures

Types of paid leave

The database collects key indicators on three specific types of paid parental leave: maternity leave, paternity leave, and shared parental leave. Maternity leave was defined as any paid leave that is reserved solely for the child’s mother, and cannot be used by or transferred to fathers or male partners. Paternity leave was defined as any paid leave that is reserved for the father or the mother’s partner – which, depending on the legislative language, may include male and/or female partners. Shared parental leave, defined as any paid leave that can be taken by either parent, includes shared leave and maternity leave entitlements that can be transferred to the father or the mother’s partner. Indicators were collected separately for birth-related leave and adoption-related leave, as many countries have unique policies that apply to each.

Duration of paid leave

The first indicator analyzed was the maximum duration of full-time maternity, paternity, and shared parental leave. To enable comparison across countries, all durations were converted into weeks. Unless sources specified otherwise, durations originally defined in working days were converted using a 5-day week, while durations originally defined in calendar days were converted using a 7-day week. When leave policies did not indicate working or calendar days, we defaulted to a 5-day week. For countries that specified durations in months, we converted to weeks by assuming 4.3 weeks per month. Only paid durations of leave were captured; in countries where leave entitlements and pay entitlements were separate, we used only the overlap period in which a parent was entitled to both full-time leave from work and some form of financial benefit. Durations of leave were captured irrespective of changes in wage replacement rates over time. For example, if a policy specified that a parent could choose to extend his or her leave at a reduced payment level, we captured the maximum duration of leave permitted.

Inclusion of same-sex couples

A second indicator categorized maternity, paternity, and shared parental leave policies as gender-inclusive, gender-neutral, or gender-restrictive. Policies were classified as gender-inclusive when same-sex partnerships were legally recognized and legislation or secondary sources specified that leave can be taken or shared with “partners,” “cohabitating partners,” “civil partners,” “registered partners,” “co-mothers,” or “co-fathers.” If same-sex partnerships were legally recognized and legislation referred only to “a parent” or “parents,” without specifying sex or gender, policies were categorized as gender-neutral. Alternatively, if same-sex partnerships were not legally recognized, policies using the term “parents” were classified as gender-restrictive. Policies were also classified as gender-restrictive when legislation utilized gendered terminology such as “mother” and “father” or when legislation specified “spouse” and same-sex partnerships were not legally recognized.

Same-sex partnerships and adoption

To determine the legal status of same-sex partnership and adoption, we utilized May 2016 data from the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA) (ILGA, 2016). ILGA has classified levels of protection for same-sex partnerships into four distinct categories: (1) marriage, (2) civil partnerships, (3) partial recognition, and (4) no recognition. Civil partnerships guarantee same-sex couples rights that are similar to those in marriage. Partial recognition grants same-sex couples some rights, such as recognition of informal cohabitation and access to inheritance, without providing many of the civil rights that are associated with marriage and civil partnership (ILGA, 2016; Waaldijk, Reference Waaldijk2005). We also documented whether same-sex couples had access to joint adoption of a child, as well as whether a non-biological parent could adopt his or her partner’s child without the loss of parental rights by either party (i.e., whether second parent adoption was legal).

Calculating the total combined duration of paid parental leave

To compare durations of available paid parental leave across different family types, we used the duration and inclusion indicators to create a variable measuring the total combined duration of birth-related and adoption-related parental leave available to each couple.

Different-sex couples

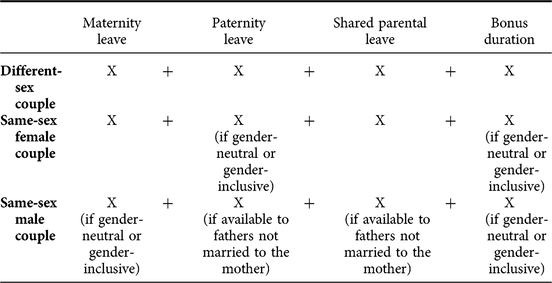

For a different-sex couple, the total duration of paid birth-related leave was calculated by summing the number of weeks of paid maternity leave, paternity leave, and shared parental leave (Table 1). For example, in Chile, a mother receives 30 weeks of maternity leave, six of which can be transferred to the father as shared parental leave, resulting in 24 weeks of maternity leave reserved solely for the mother. A father receives one additional week of paternity leave. Therefore, the couple’s total duration of paid leave would be calculated as 31 weeks.

Table 1. Calculating total combined duration of paid parental leave

For adoption-related leave, the same methodology used for calculating birth-related leave was applied using durations of leave specific to parents adopting a child.

Same-sex female couples

To calculate the combined duration of leave for same-sex female couples, assuming one woman was the biological mother, we examined whether paternity leave and shared parental leave policies were inclusive of female partners. If paternity and parental leave policies were gender-neutral or gender-inclusive, the combined duration was calculated by summing the weeks of paid maternity leave, paternity leave, and shared parental leave (Table 1). If paternity and/or parental leave policies were gender-restrictive, the duration was calculated by summing the weeks of maternity leave and shared parental leave; it did not include any duration of gender-restrictive leave that was available only to male partners, or any bonus durations of leave made available only when a father takes a certain amount of leave. In Chile, the one week of paternity leave is gender-restrictive and only available to males; thus, the total duration of leave available to a same-sex female couple would be 30 weeks.

For adoption-related leave, we first considered whether same-sex female couples were legally able to adopt a child through joint adoption or second parent adoption. If adoption was legal, we used the same methodology used to calculate birth-related leave using durations of leave available to adoptive parents. If same-sex adoption was not legal, we conclude that a same-sex female couple would receive no paid parental leave.

Same-sex male couples

To calculate the combined duration of leave for same-sex male couples, assuming one man was the biological father, the duration of leave was calculated by summing paternity leave, any shared parental leave available to a father who was not married to the child’s mother, and any additional gender-neutral leave or gender-inclusive leave that could be taken by co-fathers or partners of the biological father (Table 1). To calculate the maximum duration available to a same-sex male couple, this calculation further assumes that a birth mother transfers the entire portion of transferable maternity leave to a father, and does not take any duration of shared parental leave. Referring to the Chile example, 24 weeks of maternity leave are gender-restrictive and only available to females; therefore, the biological father would receive one week of paternity leave and the remaining six weeks of maternity leave that is transferable to the father, for a total of seven weeks.

To calculate the combined duration of adoption-related leave available to a same-sex male couple, we again considered the legality of same-sex adoption. If same-sex adoption is not legal, we calculate that a same-sex male couple would receive no paid leave. If same-sex adoption was legal, we used the same methodology used to calculate birth-related leave for a same-sex male couple using durations of leave available to adoptive parents.

Analysis

To identify differences in availability of parental leave, we first compare the number of countries providing equal durations of leave to different-sex and same-sex couples in cases of birth. To further explore the differences in leave duration, we then report the ranges of paid parental leave available to different-sex, same-sex female, and same-sex male couples across countries, as well as examining the exact differences between couples within each country. Comparisons for adoption-related leave were conducted separately, and all analyses were completed using Stata 14.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX), Microsoft Excel 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA), and ArcGIS 10.1 (Esri, Redlands, CA).

Results

Paid leave for birth parents

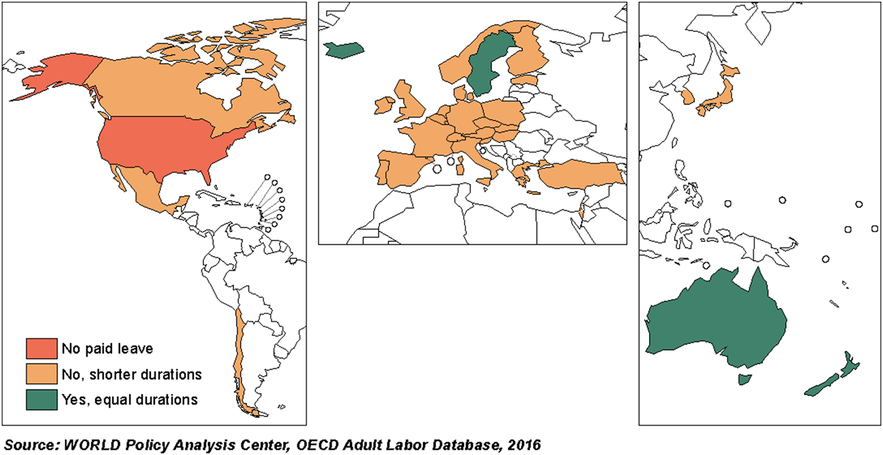

Of the 34 OECD countries, all but the United States provide paid parental leave for new birth parents. Among the 33 countries that provide paid leave, same-sex female couples receive durations of leave that are equal to those of different-sex couples in 19 countries (Figure 1). In 16 of these 19 countries, paid leave policies are either gender-inclusive, explicitly guaranteeing entitlements to female partners; gender-neutral, guaranteeing entitlements to any parent regardless of gender; or a combination of both. Two of these 19 countries (Austria and Slovakia) use gender-restrictive policy language that prohibits the couple from sharing the leave between two mothers. Therefore, in order to receive the full duration of paid leave, the biological mother must take the entire period. Switzerland is the only country in which the equal duration of paid leave available to same-sex female and different-sex couples is due solely to the absence of any paid leave available to fathers. In 14 OECD countries, same-sex female couples receive a less generous duration of leave than do different-sex couples, due to gender-restrictive policies that limit paternity leave and/or some portion of parental leave to men or fathers.

Figure 1. Do same-sex female couples receive equal durations of paid parental leave compared to different-sex couples for the birth of a child?

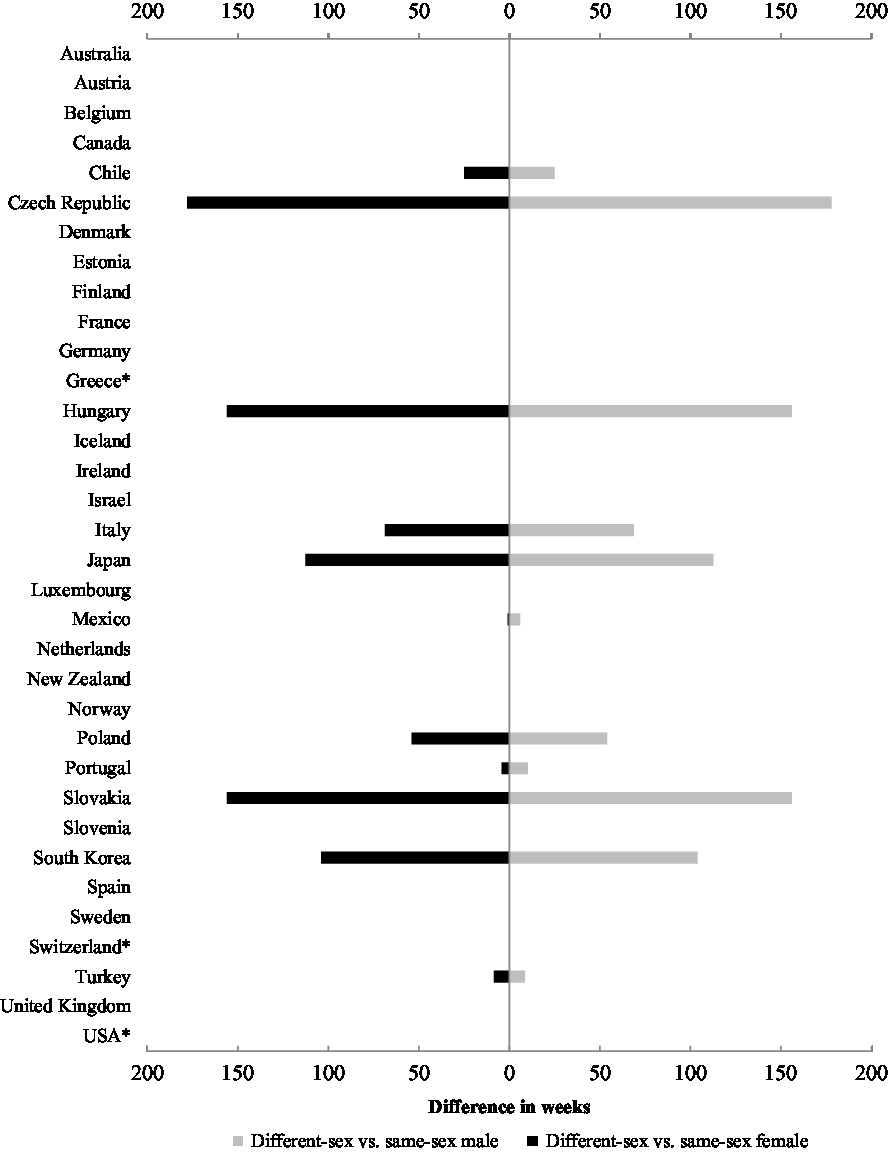

In contrast, of the 33 countries that provide paid leave to birth parents, same-sex male couples receive equal durations of parental leave as different-sex couples in only four (Australia, Iceland, New Zealand, and Sweden) countries (Figure 2). In the majority of countries (n = 29), same-sex male couples receive shorter durations of leave. In three of these 29 countries (Israel, Switzerland, and Turkey), same-sex male couples receive zero weeks of paid parental leave (Table 2). In Israel and Turkey, access to leave is restricted by paternity or shared parental leave policies that grant paid leave only to the spouse of a biological mother, thus limiting the duration a biological father who is not married to the mother can receive. In Switzerland, there is no national leave policy for fathers in same- or different-sex partnerships. Across countries, the duration of paid leave available to same-sex male couples ranges from zero weeks (in Israel, Switzerland, and Turkey) to 156 weeks in the Czech Republic. In comparison, the duration of leave that is available to same-sex female couples ranges from 12 weeks in Mexico to 164 weeks in Slovakia and the Czech Republic, while the duration of leave that is available to different-sex couples ranges from 13 weeks in Mexico to 184 weeks in the Czech Republic.

Figure 2. Do same-sex male couples receive equal durations of paid parental leave compared to different-sex couples for the birth of a child?

Table 2. Combined total duration of paid parental leave (in weeks) available to different-sex and same-sex couples for the birth of a child

a. Leave is only available to the birth mother and cannot be shared with female partners.

Figure 3 further highlights that same-sex male couples receive markedly less leave than both different-sex and same-sex female couples. The difference in durations of leave available to same-sex female couples and different-sex couples ranges from less than a week in Greece, Israel, and Luxembourg, to over a year in Japan and Korea, with an average difference of nearly three months (12 weeks). On average, same-sex male couples receive five fewer months (22 weeks) of leave than different-sex couples, with the differences ranging from two weeks in the United Kingdom to over a year in Hungary, Japan, and South Korea.

Figure 3. Differences in the duration of paid parental leave available to different-sex and same-sex couples for the birth of a child

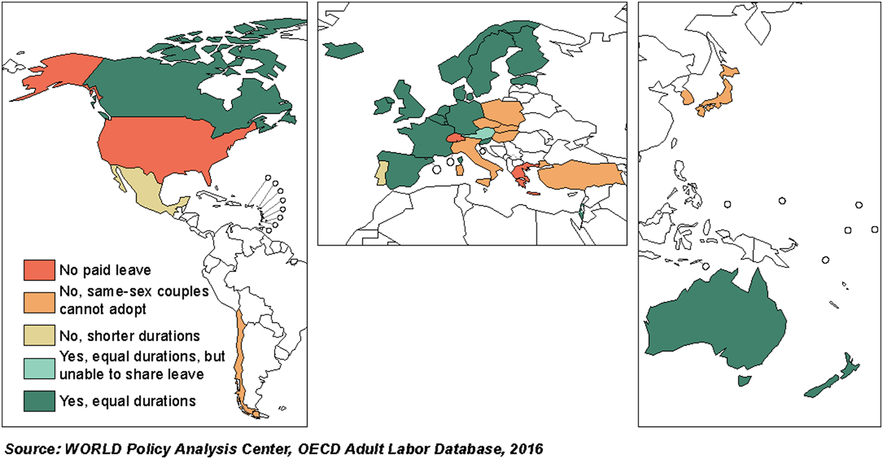

Paid leave for adoption

Three OECD countries (Greece, Switzerland, and the United States) do not provide any paid leave to adoptive parents (Figure 4). Among the 31 countries that have paid parental leave for adoption, the most common barrier to equal durations of leave for same-sex couples is the inability to legally adopt a child. Nine of the 31 countries do not allow joint or second parent adoption for same-sex couples, effectively eliminating their access to legal parent status and any associated entitlement to leave. In the remaining 22 countries that allow either form of adoption for same-sex couples, only two (Mexico and Portugal) provide same-sex male and female couples with durations of paid adoption leave that are shorter than those for different-sex couples. The majority of countries (n = 19) provide equal durations of paid adoption leave to same-sex couples as different-sex couples. One country (Austria) provides equal durations of leave, but the gender-restrictive language prevents a same-sex couple from sharing the leave, requiring one parent to take the entire duration.

Figure 4. Do same-sex couples receive equal durations of paid parental leave compared to different-sex couples for the adoption of a child?

Among the total 31 countries with paid parental leave for adoption, the duration of leave for different-sex parents ranges from seven weeks in Mexico to 178 weeks in the Czech Republic (Table 3). For same-sex couples, the duration of paid leave ranges from zero weeks in countries where same-sex adoption is not legal, to 104 weeks in Austria.

Table 3. Combined total duration of paid parental leave (in weeks) available to different-sex and same-sex couples for the adoption of a child

a. Same-sex adoption is not legal.

b. Leave is only available to one parent and cannot be shared with same-sex partners.

c. 2016 data from the International Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans and Intersex Association (ILGA) report that second parent adoption is legal. However, correspondence with in-country researchers confirms it was not legal in 2016 and is not currently legal. This was cross-checked with 2015 and 2017 ILGA data.

The differences in duration of leave between different-sex and same-sex couples in cases of adoption show again that same-sex male couples experience greater disparities in the availability of paid parental leave (Figure 5). The difference in leave duration between different-sex and same-sex female couples is one week and 4.3 weeks in Mexico and Portugal, respectively, whereas the difference between different-sex and same-sex male couples is six weeks in Mexico and 10.3 weeks in Portugal. In countries where same-sex adoption is not legal, same-sex female couples and same-sex male couples are equally disadvantaged, as they both lack access to parenthood.

Figure 5. Differences in the duration of paid parental leave available to different-sex and same-sex couples for the adoption of a child

Of the 33 OECD countries with any paid parental leave for birth or adoption, only four – Australia, Iceland, New Zealand, and Sweden – utilize gender-neutral or gender-inclusive language guaranteeing all birth and adoptive parents equal leave entitlements regardless of their sex or partnership status.

Discussion

This study provides a comparison of different-sex and same-sex couples’ paid parental leave entitlements in 34 OECD countries. Despite mounting evidence that more generous durations of paid parental leave can boost families’ health and economic opportunities, we find that not all parents receive equal leave entitlements. This study concludes that differential availability of paid leave may ensue from gender inequalities in the law and the disproportionate placement of caregiving burdens on women, which then disadvantage same-sex male couples. In a few countries, more recent policies may incentivize leave for fathers in different-sex partnerships without providing equivalent options for same-sex female couples. Differential access may also be due to inequality in marriage and adoption rights for same-sex couples.

While in cases of birth, differences in the duration of paid leave available to same-sex male couples may issue partly from leave intended to accommodate birth mothers’ pre- and postpartum needs, the disparities are sometimes far greater than could be suggested by biological needs. Potential complications associated with childbirth may not resolve until four to six weeks postpartum, and recovery periods from cesarean deliveries may extend to eight weeks postpartum (American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2008, 2011; Sibai and Frangieh, Reference Sibai and Frangieh1995; Williams and Hoffman, Reference Williams and Hoffman2012). Durations of paid leave reserved for biological mothers may also be needed to facilitate exclusive breastfeeding, which is recommended for at least six months by the World Health Organization. However, reserving leave for biological mothers without reserving a similar duration for fathers may result in same-sex male couples receiving shorter durations of paid parental leave. In the seven countries where differences in the duration of paid leave available to same-sex male couples and to different-sex couples total six months or more, same-sex male parents and their children may be at a significant disadvantage – especially when considering other benefits of paid leave, including bonding time with children, the ability to ensure that children receive all recommended preventive care, and the opportunity to divide caregiving responsibilities equally between partners. Additionally, there are 14 countries where same-sex female couples receive shorter durations of paid leave due to female partners not having access to paternity leave and/or shared parental leave, despite there being no biological rationale in terms of recovery from childbirth.

Further, gender-restrictive parental leave policies that preclude one parent from taking any leave may also affect same-sex couples by requiring one partner to be the sole caregiver without receiving support from a partner at home. Such lack of partner support may be equally detrimental to female and male primary caregivers, given the link between lack of social support and depressive symptoms among both single mothers and single fathers (Chiu et al., Reference Chiu, Rahman, Kurdyak, Cairney, Jembere and Vigod2017; Crosier et al., Reference Crosier, Butterworth and Rodgers2007; Kong and Kim, Reference Kong and Kim2015; Ravanera, Reference Ravanera2007; Rousou et al., Reference Rousou, Kouta and Middleton2016).

Regardless of sex, gender identity, or sexual orientation, all parents and children benefit when parents can access paid leave to care for and bond with their newly adopted children. Yet there are 11 countries in which same-sex couples receive shorter durations of paid leave for adoption compared to different-sex couples. In nine of these countries, these disparities stem from same-sex couples’ lack of legal access to any form of adoption, which uniformly disadvantages same-sex female and same-sex male couples. In the remaining two countries (Mexico and Portugal), same-sex male couples are at a marked disadvantage compared not only to different-sex couples, but also to same-sex female couples. In both countries, these disparities are due partly or entirely to paid leave policies that allocate a substantially longer period of leave to mothers than to fathers. In addition to perpetuating gender inequalities in caregiving responsibilities, this type of policy design leaves same-sex male couples and their children with limited access to the wide-ranging health, economic, and developmental benefits of paid parental leave.

Differences in the duration of paid leave available to same- and different-sex couples may also result from incentive schemes designed to increase leave uptake by fathers in different-sex partnerships. As the benefits of fathers’ involvement in child care gain increasing recognition, some countries have come to employ gender-restrictive language reserving a certain period of paid leave exclusively for fathers, thereby ensuring that men in different-sex couples do not transfer their leave to their children’s mothers. Policies may also offer bonuses or other incentives, such as higher rates of wage replacement, to encourage fathers in different-sex couples to take some length of shared parental leave, rather than delegating leave – and therefore caregiving responsibility – solely or primarily to a child’s mother. Such incentives have been shown to be effective at promoting fathers’ take-up of parental leave (Ekberg et al., Reference Ekberg, Eriksson and Friebel2013; Twamley and Schober, Reference Twamley and Schober2018), as well as fathers’ involvement in child care within different-sex partnerships (Haas and Hwang, Reference Haas and Hwang2008; Kotsadam and Finseraas, Reference Kotsadam and Finseraas2011; Nepomnyaschy and Waldfogel, Reference Nepomnyaschy and Waldfogel2007; Patnaik, Reference Patnaik2017; Tanaka and Waldfogel, Reference Tanaka and Waldfogel2007). However, unless these policies describe co-parents in gender-neutral language, they may also inadvertently disadvantage families with two female parents by restricting leave to male parents. By being more cognizant of diverse family structures, policymakers can preserve these benefits while drafting legislation in ways that extend equitable benefits to all family types.

The results of our analyses also highlight the importance of considering paid leave policies within the context of other family-related policies when assessing the equitability of access across gender and family types. Availability of paid leave may often depend on policies that recognize or deny same-sex couples’ right to start and care for their families. Without legal recognition of their partnerships, same-sex couples may face restrictions on their ability to access parental rights, including paid leave, which are reserved for married couples. South Korea, Turkey, and Israel restrict all or a portion of paid leave to fathers whose “spouse” is giving birth, thus restricting female partners in same-sex female partnerships and unmarried biological fathers in same-sex male partnerships from receiving the full duration of paid leave for the birth of a child. Denying the right to legal partnership may also prevent parents in a same-sex partnership from both being recognized as the legal guardians of a child, which may limit the availability of paid leave even when a country’s leave policies are gender-neutral. For example, Poland allows both parents of a child to share a period of parental leave, without specifying the gender of each parent. However, with Poland’s lack of recognition for same-sex partnerships, it is unlikely that two parents of the same sex could become legal co-parents of a child and share this duration of leave.

Similarly, the most common barrier to equal durations of adoption leave for same-sex couples is the inability of same-sex couples to legally adopt children. In the 15 OECD countries where joint adoption is not legal for same-sex couples, lesbian and gay couples may not have access to joint parental rights or adoption-related leave. Where same-sex joint adoption is not permitted, one partner may be able to adopt a child as a sole parent; if second parent adoption is legal, the other partner may be able to subsequently adopt the child. However, second parent adoption can be a costly and time-intensive process, placing an added financial burden on new families and possibly preventing partners from accessing paid leave during a crucial period for child development and bonding (Chang, Reference Chang2017; Huerta et al., Reference Huerta, Adema, Baxter, Han, Lausten, Lee and Waldfogel2013; Human Rights Campaign, 2017; Ruhm, Reference Ruhm2004; Waldfogel et al., Reference Waldfogel, Han and Brooks-Gunn2002). Lack of legal access to assisted reproductive technologies, including artificial insemination and surrogacy, can be an additional barrier for same-sex couples to becoming biological parents. It is essential for policymakers to recognize that paid leave policies do not operate in a vacuum, and should be designed alongside other family policies.

These analyses have limitations that are important to note. First, we relied on language in primary legislation and official government websites to determine how and when paid parental leave policies were applied to same-sex couples. However, gender-restrictive language does not always translate into inequality in the availability of benefits. In some countries, same-sex partners may have opportunities to gain access to parental leave through the court systems.1 Researchers may consider exploring case law in future analyses to assess alternative approaches to extending parental leave rights to same-sex couples.

Second, this analysis focuses on duration of leave, which is one aspect in which same-sex couples may be disadvantaged when accessing paid parental leave. Future analyses should examine additional aspects of paid leave policies, such as varying wage replacement rates for mothers and fathers, which may also disadvantage same-sex couples. Future researchers may also consider approaches to understanding other legal or cultural barriers to paid parental leave, including parental rights following assistive reproductive treatments methods such as surrogacy.

Lastly, our sample was restricted to 34 OECD countries; this concentrated sample allowed us to develop and implement a new approach to evaluating paid leave policies, but it does also limit our global applicability. Similar analyses that utilize a larger sample of countries may be necessary to look more closely at regional and income-level trends. We examined countries according to previous literature around family policy, gendered division of labor, and the welfare state, and found no consistent pattern in either the duration of paid leave available to different family types or the inclusivity of legislative language by established welfare state typologies (Gornick et al., Reference Gornick, Meyers and Ross1997; Ray et al., Reference Ray, Gornick and Schmitt2010). An expanded sample of countries could also support further research examining the congruence between the origins of inclusive social policies and approaches to state policy.

While further research would be valuable, our findings indicate same-sex couples often receive shorter durations of paid parental leave in comparison to different-sex couples; this is particularly true for male same-sex partners. Although no legislation explicitly prohibits same-sex couples from receiving paid parental leave, many of the differences in duration of leave may be indirect consequences of heteronormative and gendered assumptions about family and caregiving. Policymakers can eliminate disparities in access for same-sex couples and increase gender equality for different-sex couples by removing gendered and heteronormative language that designates women as primary caregivers and assumes that every family has one mother and one father. Substituting gender-neutral or gender-inclusive language that extends leave entitlements to all parents, including non-biological parents, regardless of gender, would have wide benefits. Addressing these issues is critical to developing policies that ensure children’s and parents’ equitable access to the health and economic benefits of paid parental leave.